Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Increasing use of gastrointestinal endoscopy, particularly for colorectal cancer screening, and increasing emphasis on health care quality highlight the need for endoscopy facilities to review the quality of the service they offer.

OBJECTIVE:

To adapt the United Kingdom Global Rating Scale (UK-GRS) to develop a web-based and patient-centred tool to assess and improve the quality of endoscopy services provided.

METHODS:

Based on feedback from 22 sites across Canada that completed the UK endoscopy GRS, and integrating results of the Canadian consensus on safety and quality indicators in endoscopy and other Canadian consensus reports, a working group of endoscopists experienced with the GRS developed the GRS-Canada (GRS-C).

RESULTS:

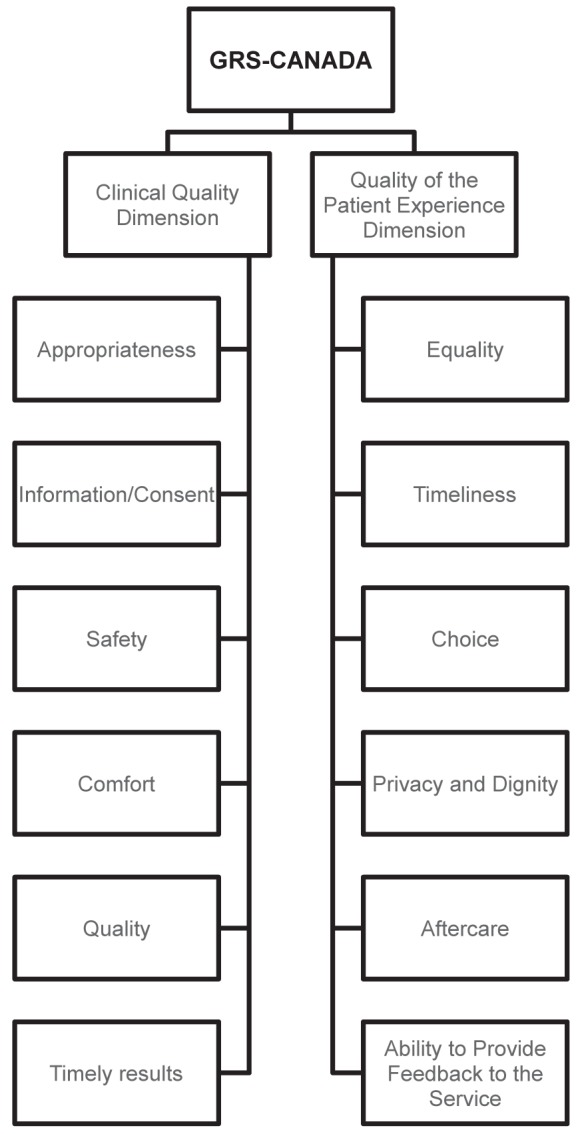

The GRS-C mirrors the two dimensions (clinical quality and quality of the patient experience) and 12 patient-centred items of the UK-GRS, but was modified to apply to Canadian health care infrastructure, language and current practice. Each item is assessed by a yes/no response to eight to 12 statements that are divided into levels graded D (basic) through A (advanced). A core team consisting of a booking clerk, charge nurse and the physician responsible for the unit is recommended to complete the GRS-C twice yearly.

CONCLUSION:

The GRS-C is intended to improve endoscopic services in Canada by providing endoscopy units with a straightforward process to review the quality of the service they provide.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Global rating scale, GRS, Quality

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’utilisation croissante de l’endoscopie gastro-intesti-nale, notamment dans le cadre du dépistage du cancer colorectal, et l’importance croissante accordée à la qualité des soins font ressortir la nécessité, pour les établissements d’endoscopie, de revoir la qualité des services offerts.

OBJECTIF :

Adapter l’échelle de classement global du Royaume-Uni (ÉCG-RU) pour mettre au point un outil virtuel et axé sur le patient en vue d’évaluer et d’améliorer la qualité des services d’endoscopie.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

D’après les commentaires de 22 emplacements au Canada qui ont rempli l’ÉCG-RU en endoscopie et après y avoir intégré les résultats du consensus canadien sur les indicateurs de sécurité et de qualité en endoscopie ainsi que d’autres rapports consensuels cana-diens, un groupe de travail d’endoscopistes connaissant l’ÉCG a préparé l’ÉCG-Canada (ÉCG-C).

RÉSULTATS :

L’ÉCG-C reprend les deux dimensions (qualité clinique et qualité de l’expérience des patients) et les12 éléments axés sur le patient de l’ÉCG-RU, mais modifiés pour s’appliquer à l’infrastructure des soins de santé canadiens, à la langue et à la pratique actuelle. Chaque élément est évalué par une réponse oui-non à huit des 12 déclarations divisées en niveaux classés de D (de base) à A (avancé). Il est recommandé qu’une équipe principale, composée d’un préposé aux ren-dez-vous, d’une infirmière responsable et du médecin responsable de l’unité, remplisse l’ÉCG-C deux fois l’an.

CONCLUSION :

L’ÉCG-C vise à améliorer les services d’endoscopie au Canada en fournissant aux unités d’endoscopie un processus simple pour évaluer la qualité de leurs services.

The importance of ensuring quality care in endoscopy is now widely supported. On one hand, colorectal cancer screening programs aim to ensure that individuals screened, who are otherwise well and healthy, are not subjected to undue harms through the process of screening. On the other hand, endoscopy is a high-volume service that provides care that, in many respects, can be standardized according to evidence and best practices. It is also recognized that quality endoscopy care is multifaceted and based on desired outcomes and perspectives such as timeliness, safety, efficiency and equity.

In 2004, the results of a prospective multicentre audit of the provision of colonoscopy service in the United Kingdom (UK) were published (1). This audit revealed significant deficiencies in the quality of colonoscopy service being performed at that time. Similarly, practice audits in Canada have shown considerable variation in colonoscopy wait times across Canada (2). To address these deficiencies in the UK, an accreditation process for endoscopy units was developed and endoscopy education and training courses for endoscopists were introduced. In addition, a web-based, patient-centred quality improvement tool for endoscopy units was developed, the endoscopy Global Rating Scale (GRS) (3).

The GRS is a web-based tool that aids endoscopy units in assessing the quality of the service they provide. It was developed following discussions with endoscopy staff, health care providers and patient groups who evaluated factors that they considered to be important to a patient undergoing endoscopy. Twice each year, endoscopy centres review the quality of their service using the GRS and enter their data into the supporting website (4). There has been widespread acceptance and use of the GRS in England, which has resulted in substantial improvements in the quality of endoscopic services provided, along with a pronounced reduction in wait times for endoscopy (5). It has become mandatory for endoscopy units to participate in the GRS and obtain level B quality indicators if they want to be involved in colon cancer screening in the UK. The GRS has now also been successfully introduced to Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland (4).

In response to surveys demonstrating public dissatisfaction with wait times for specialist care in Canada (6,7) and media accounts of excessive delays, the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) organized a meeting in 2005 to develop a consensus on acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Recommendations were developed for wait-time targets and triage categories for gastrointestinal consultation (8). The CAG subsequently developed a pilot project known as the Quality Program in Endoscopy (QP-E). The QP-E was launched in Canada at 22 sites with a twofold purpose: endoscopy services were to regularly perform the GRS (using the original UK version) while endoscopists were also required to use a personal practice audit tool for outpatient colonoscopy (9).

Initial exposure to the QP-E in Canada was generally positive (10). Feedback from these pilot sites noted that use of the GRS engaged and empowered staff to generate and participate in quality improvement initiatives. The GRS arm of the project was useful for identifying service gaps and proposing improvements to unit efficiency. However, despite the potential benefits observed with the pilot study, it became evident that the UK version of the GRS needed revision and modification regarding health care infrastructure, language and current practice to apply to the Canadian health care system. For example, reference to British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines, trusts and other terminology not commonly used in Canada required updating.

In an effort to improve the quality of endoscopy services in Canada, a decision was made to develop a relevant, timely and effective tool based on the UK-GRS. In the present article, we describe the development and use of this tool, with the aim of encouraging widespread use of the GRS concept in Canada.

METHODS

Working group

As part of the continuing process to improve the quality of Canadian endoscopy services, a consensus meeting of representative Canadian and international experts was held in Toronto (Ontario) in June 2010 (11). The aims of this meeting were to develop a consensus on broadly applicable standards and key indicators to support quality improvement in endoscopy. As part of the consensus activity, a working group was identified to adapt the GRS for use in Canada. Led by Donald MacIntosh, the group consisted of experienced endoscopist leads who had used the GRS in the pilot and/or who had published work regarding the GRS (Catherine Dubé, Roger Hollingworth, George Ghattas, Sander Veldhuyzen van Zanten) in conjunction with participation from Roland Valori, who was one of the authors of the UK-GRS. This group undertook the task of developing a Canadian GRS (GRS-C) – a relevant, timely and effective tool for improving endoscopy care in Canada.

Development of the GRS-C

Development of the GRS-C was performed by the working group in collaboration with a team of representatives in their respective units. Suggestions for improvement were derived from annual meetings of the pilot group, recommendations from provincial screening programs, as well as from observations made with the use of the UK-GRS for more than two years in six units: one in Halifax (Nova Scotia), one in Mississauga (Ontario) and four in Calgary (Alberta), which are in academic as well as community-based centres. Drafts of the GRS-C were reworked among the groups, and also shared with both Roland Valori and Debbie Johnston, who collaboratively authored the UK-GRS. These two experts also provided the working group with the 2011 updated GRS, which was then integrated, as appropriate, into the GRS-C. Results of the Canadian consensus on quality and safety in endoscopy and of other Canadian consensus reports (8,11,12) were also integrated or referenced, as appropriate.

Structure of the GRS-C

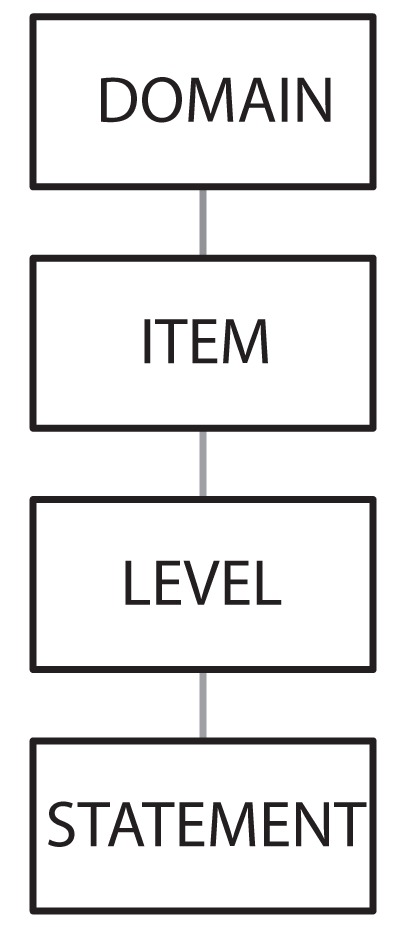

The GRS-C was designed using the basic structure of the original UK-GRS, including domains, items, levels and statements (Figure 1) (3). The GRS-C was based on the domains of clinical quality and quality of the patient experience. Each of these domains consisted of six different items, such as comfort and timeliness, which are assessed by a yes/no response to eight to 12 statements. The statements were divided into levels graded D (basic) through A (advanced) (Table 1), with one to five statements per level. During development, new statements were added and pre-existing statements were altered, rearranged or removed to make the instrument more applicable to the Canadian environment. It was also agreed that the distinction between levels would be, as much as possible, based on the degree of integration of a quality assurance cycle, as outlined in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of the Global Rating Scale

TABLE 1.

Levels and corresponding activities

| Level | Activity |

|---|---|

| D | Basic data gathering |

| C | Periodic review of data gathered, including patient satisfaction surveys |

| B | Response to opportunities for improvement identified |

| A | Assess response to changes made |

Moreover, similar to the UK-GRS, the GRS-C is supported by a website that provides a site for data entry by endoscopy units, an action planning tool, and an electronic library of policies and forms that enable document sharing (3).

RESULTS

The final version of the GRS-C is presented, along with recommendations regarding the use of the scale, and explanations of the different items (Appendix 1: GRS-C).

Overview of GRS-C

The structure of the final survey is similar to that of the UK-GRS (Figure 1). The 12 items discussed in the following sections (Figure 2) are rated based on yes or no responses to the statements. To attain a specific level (A to D), all statements within that level, as well as the level(s), below must be answered as ‘yes’. For each of the items, at the basic level (D), endoscopic units should keep good records of procedures or patient satisfaction. At level C, these data should be periodically reviewed to identify areas for improvement; to advance to level B, action should be taken to address these issues. To attain level A for an item, there should be an assessment process that evaluates the impact of any actions taken.

Figure 2.

Items of the Global Rating Scale (GRS) – Canada

Using the GRS-C

The GRS-C survey should be performed twice per year (April and October). The online survey can be completed in 1 h to 2 h. The unit’s responses are entered into the GRS-C website (13), including action plans for the next six-month assessment. The library associated with the GRS-C website will provide material, such as sample patient surveys, that can be adapted by each unit for local needs. A variety of materials will be available for use on this site, including samples such as comfort scores and procedure pamphlets.

On embarking with the GRS-C, it is recommended that endoscopy units develop a team consisting of a minimum of three to four members, including a booking clerk, charge nurse and the physician responsible for the unit as the basic core group. Additional members, including patient representatives, can also be added. This group could be expanded into a regional GRS committee in which results, challenges and successes can be discussed. These activities are easily integrated as part of the endoscopy committees that already exist in many centres.

The authors recommend an initial assessment to evaluate the unit’s current rating. At this initial assessment, most Canadian units are likely to be level D or below. It should be stressed that a ‘D’ is not a failing grade but will be the starting point of most endoscopy units. Not fulfilling a ‘D’ level in the GRS does not necessarily imply poor performance; rather, it means that there is no system in place to measure, record and review unit performance. D grades, however, should illustrate that units need to improve and should not be satisfied with the current state of affairs.

At the time of the original assessment, it is recommended that the unit develop two or three easily achievable action plans. Many resources will be available in the library to help units achieve the goals of their action plans. With each subsequent six-month evaluation, new action plans can be developed, with the ultimate aim of reaching B or A levels in all categories. Finally, in keeping with the patient-centred philosophy of the GRS, to complete the C level of several items of the GRS-C, patient satisfaction surveys should be performed at least annually.

DISCUSSION

1. Consent process including patient information

• Patient consent is required before an endoscopic procedure or preparation for a procedure is initiated (11)

Canadian medicolegal jurisprudence currently requires that patients be informed of all relevant information related to the procedure including risks, benefits, alternatives and sedation options, and that patients be provided with an opportunity to ask questions that the physician or assistants must answer. On the day of the procedure, it is the responsibility of the endoscopist to ensure that the consent process is completed appropriately and that the consent form is signed (14). This has particular implications in Canada given the wide variety of referral/practice patterns across the country.

Direct access to endoscopy (ie, without a previous visit or consultation in the office) is feasible only if information about the procedure is provided in a timely fashion that allows the patient an opportunity to ask questions and be satisfied that questions have been answered. Procedure-related information can be provided directly by a health care provider or via leaflets or websites. However, even with previous notification, the endoscopist remains responsible for ascertaining that the consent process has been fully performed.

At the basic level (ie, ‘D’), the facility should have published information regarding all endoscopic procedures performed in the unit. This information should be provided before the patient visits the facility. In general, hospitals in Canada have institution-wide consent policies, and freestanding endoscopy facilities should also ensure consent policies are in place. Annual patient surveys about the consent process and about the quality of the information provided to the patient before the procedure moves the unit to a C level. Review of survey results and incorporation of these results into procedure brochures raises the unit to B and A levels.

2. Safety

• Complications and adverse events should be recorded

Facilities should record complications and adverse events to detect and monitor recurring patterns or unusual numbers of events related to endoscopy. Delayed events, in particular, may be difficult to detect in scenarios in which the patient may not return to the same facility for follow-up care. The relative infrequency of unplanned events obviates a reporting system in the facility rather than chart audit to allow detection of endoscopy-related events.

Recording endoscopy safety involves more than simple documentation of obvious procedural complications such as perforation or post-polypectomy bleeding (5). Excess sedation use, particularly in the elderly, or frequent use of reversal agents also raises questions about procedural safety. A suggested list of endoscopy safety indicators that should be captured by Canadian endoscopy units is available in a recent publication by Borgaonkar et al (15).

Quality assurance of infection control is required to assess the excellence of high-level disinfection of endoscopic equipment. This should include adherence to manufacturers’ instructions and assessment of the quality of water supply and filtration systems. This is an essential requirement for any endoscopy service.

To move a unit beyond basic record keeping (level D), the facility should regularly review adverse events and report results to endoscop-ists working in the facility (C). To measure delayed events, a system such as telephone follow-up, a mail-back questionnaire or an electronic reporting system, should be used to capture potential complications within two weeks of a procedure. For the unit to reach an advanced level (A or B), it should conduct committee reviews of complications and adverse events. The committee should agree on changes that could be implemented to reduce or avoid future events and should also assess the effectiveness of these changes.

3. Comfort

• Patient comfort levels should be monitored throughout the endoscopic procedure and during recovery

In Canada, most endoscopies are performed using conscious sedation rather than general anesthesia. Regardless of the type of anesthesia offered to patients, comfort assessment during both the procedure and the recovery period is essential to the provision of a quality patient experience.

At the basic level (D), monitoring of patient comfort by nursing staff should be routine for all endoscopic procedures. To advance the level of care provided to level C, the endoscopy facility should monitor and record patient comfort levels in a structured fashion. A validated tool such as the Calgary Nurse Assessed Patient Comfort Scale (NAPCOMS) (16), available on the GRS-C library site, could be used for this purpose. This tool enables comparison among endoscopists to ensure that all health care providers in the facility meet target levels of comfort. To avoid potential bias, a health care provider other than the endoscopist should perform the recording of patient comfort during the procedure. For the unit to achieve the upper levels in comfort quality (A or B), all endoscopists in the facility should receive feedback on their comfort scores. An endoscopist’s practice should be reviewed if using NAPCOMS, they frequently exceed threshold comfort scores. In this circumstance, endoscopists should be encouraged to participate in a training course to help improve their overall technique.

If a patient experiences excessive discomfort during an endoscopy, the procedure should be paused. At this point, the endoscopist should review the technique for technical problems, such as unrecognized looping and excessive insufflation of air; consider administering additional sedation (subject to requirement and safety); and assess the option of aborting the procedure. NAPCOMS also provides a threshold score that triggers such a procedural pause to review technique, sedation and indication.

4. Quality indicators

• Indicators of the technical quality of endoscopic procedures should be measured

Key performance indicators (KPIs) of the technical aspects of the endoscopy procedure include cecal intubation rates, withdrawal times, polyp detection and adenoma detection rates (11,17). Bowel preparation is a key quality indicator and should also be appraised and regularly monitored. Poor quality bowel preparation can lead to prolonged procedures, increased patient discomfort, missed lesions and, ultimately, avoidable repetition of procedures (18).

KPIs are not limited to technical assessments of the procedure itself. Endoscopy facilities should also monitor their adherence to pre-procedure guidelines such as the American Heart Association antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines (19) and American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy antithrombotic guidelines (20).

At the basic level (D), endoscopy units need to develop systems for recording endoscopy-related quality indicators. Endoscopists should receive feedback on their performance with comparisons with their peers (21). Gathering such data with review and notification of results should help to monitor the performance of endoscopists in the unit and to detect any problems with their practice (level C). To attain B level, units should develop action plans, when needed, to improve endoscopist performance. This should be regarded as an opportunity to improve endoscopist skills with additional training such as ‘Train-The-Trainer’ or ‘Up-Skilling’ endoscopy courses offered by the CAG. At an A level, the unit reassesses the impact of changes made to improve performance within a defined time frame.

5. Appropriateness

• Consensus guidelines should be followed regarding the reasons for performing endoscopic procedures

Wait times for endoscopy in Canada continue to increase, with rising demands from the public as well as from provincial colon cancer screening programs. It is, therefore, important to ensure that endoscopy procedures are only performed at appropriate times to achieve effective and efficient wait-time management. Consensus guidelines have been published that list detailed indications and scenarios in which endoscopic procedures, including screening and surveillance endoscopy, should be performed (22,23). Unfortunately, it has been demonstrated that many procedures are performed for inappropriate reasons (24,25): that recommended screening and surveillance intervals are infrequently adhered to (26); and that endoscopic procedures are performed unnecessarily (27,28). Furthermore, there is evidence of problems among Canadian endoscopists adhering to screening and follow-up surveillance guidelines for colon cancer screening (29,30).

One measure that may help to address this would be to provide relevant information to physicians who refer patients for direct-to-procedure endoscopy. This should inform physicians of the specific indications or circumstances under which direct endoscopy will be offered. It should also include a lists of medications that patients should not take before the procedure, such as anticoagulants.

Basic level (D) requirements for the GRS-C include ensuring that endoscopies are scheduled following published screening and surveillance guidelines, and auditing adherence to these guidelines to ensure acceptable levels of efficiency (23,31–34). To obtain C level, units should perform annual audits of adherence to guidelines with endoscopist notification of results. Advanced level facilities should respond to problems detected by audits (Level B) and review the effect of changes within a predetermined period of time (Level A).

6. Communicating results

• The results of endoscopic procedures should be communicated in a timely manner, both to the patient and to the referring physician

Timely communication of results is frequently rated highly in patient surveys (35); however, patients often leave endoscopy units without knowing when they will receive their results or without clear discharge and follow-up plans (10). It is the endoscopist’s responsibility to ensure that results are communicated to the patient. If another health care provider will be informing the patient of their results, both the patient and their health care provider will need to be notified.

Documenting any findings and reporting them to the referring physician are key aspects of a quality procedure. Improving the quality and consistency of endoscopy reports is best accomplished by electronic endoscopy reporting systems using mandatory reporting fields (36,37). The use of electronic reporting systems is encouraged to improve the quality of reporting. This can also offer the capability of immediate communication of results to referring physicians. In addition, standardized reporting templates can be enriched with up-to-date guidelines, which serve to educate referring physicians at the same time as serving patient care.

It is also the responsibility of the endoscopist to ensure that pathology reports are reviewed and acted on as necessary. Patients need to be informed whether biopsies were taken, given an estimate of the time required to review the pathology report and of how these results, as well as their impact on the management plan, will be communicated to them.

At the basic level (D), facilities should have specific requirements and standardized elements in their reports (11). C-level units have developed a standardized list of elements for their endoscopy reports and audit adherence to these standardized reports. To advance the unit to higher levels (A or B), plans should be made to improve suboptimal reporting with appropriate follow-up assessment of any actions taken. Electronic reporting systems are also recommended to facilitate the use of standardized reports and improve communication with referring physicians.

7. Equality

• Endoscopy procedures should be available to everyone

Similar to other areas of health care in Canada, physical disability, race, creed or culture should not limit access to endoscopy services. In addition, information should be available to patients and family members in the prevalent languages of the community. Because the language profile of regional populations vary greatly in Canada, units must be aware of their own populations’ needs. Where necessary, the provision of interpreters is essential for safe, quality endoscopy.

All facilities should have basic policies regarding equality of access sensitive to the needs of their local population (level D). To improve the quality of the endoscopy service to level C, facilities could perform formal community surveys; however, asking staff members who schedule patients for endoscopy in the facility is the simplest way to determine the needs of each community. Annual patient surveys can be a good way to elicit useful feedback. To reach B and A levels, units should respond to any problems found in the survey with timely follow-up to assess the impact of any changes made.

8. Timeliness

• Endoscopy triage and wait-time management should be related to the Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health problems (8)

There are a variety of possible options to shorten wait times including a central booking system, to back-fill open slots or cancellations, or pooling of endoscopy lists. Pooling of endoscopy lists would require adequate notification of endoscopist vacation times, which would allow other endoscopists to access these slots. Other options include setting up a roster of urgent-access endoscopy slots, allowing other physicians to directly refer cases that meet predetermined criteria.

When a facility assesses wait times, responses should be graded according to the longest time noted in a group practice (level D). C-level units record wait times and communicate these results to team members and referring physicians. As the facility improves to B or A level, measuring and reporting wait times should lead to system changes that improve patient access to endoscopy.

It is important to note that, with respect to colonoscopy wait times in patients with an abnormal fecal occult blood test, guidelines should follow those of the screening programs. The eight-week wait time as established by CAG was based on a gastroenterology practice’s perspective and before the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) became available. Based on the increased likelihood of significant findings in patients with positive FIT, as suggested by recent European colorectal cancer screening guidelines, the suggested eight-week target is likely too long. A target of colonoscopy within 30 days is suggested for patients with positive FIT (23).

9. Booking

• Adaptations to the booking process could help to improve attendance

Letters or telephone calls reminding patients of their appointments and monitoring no-show/cancellation rates have improved the utilization of endoscopy appointments and should be standard in all units (level D). C-level units measure no show/cancellation rates and notify referring physicians when their patient misses an appointment. Feedback is obtained in annual surveys regarding the booking process. Level-B units respond to problems identified in the annual survey and offer their patients a choice when booking an appointment, which can also help to improve attendance. This may simply mean offering morning versus afternoon appointments or offering different days of the week. Booking choice may be easier in the context of pooled endoscopy lists and a central booking capability. A-level units monitor the response to any changes made in the booking process with further patient follow-up.

10. Privacy and dignity

• A patient’s right to privacy and the expectation to be treated with dignity are central to Canadian health care

To achieve level-D status, dedicated recovery rooms and secure space for belongings should be available. These are basic requirements and should be available in all endoscopy units. It is important not to add to any distress about discomfort and worrying diagnoses, or other concerns a patient may have when coming in for an invasive procedure. Discussion of results within earshot of other patients and families should be avoided, and patients should have the option to discuss their results in private. C-level units provide a quiet room for private conversation and survey patient opinion on their treatment with respect to privacy and dignity. To be a more advanced unit (A or B), the facility responds to identified problems and assesses the effectiveness of changes made. Ideally, pre- and postprocedure patients should be kept in separate areas of the facility. This option may be restricted by physical space limitations but should be the goal of any unit undergoing renovation or space increase.

11. Aftercare

• Patients should be discharged with clear, written instructions and information

The majority of patients appreciate receiving results on the same day of their procedure (35). It is important that patients receive results in a timely fashion and leave the facility with clear discharge instructions, given either to them or to family members, which include information about potential complications and contact details. A follow-up contact number should preferably be available 24 h per day. It could be office or facility based, or could be a 24 h emergency telephone service provided in the community.

In cases for which surveillance or follow-up procedures are required, it is important that the patient is made aware of the person responsible for organizing any future appointments. Ideally, they should be informed in writing by the endoscopist for the avoidance of any confusion, and the referring physician should also be notified. Written instructions are preferable postsedation and are less likely to lead to confusion than spoken instructions.

At the basic level (D), patients should receive clear instructions regarding the follow-up process. To advance to higher levels, annual surveys of aftercare instructions should be performed (level C). A- and B-level units respond to any problems identified by these surveys and assess the effect of changes made. These efforts should lead to a significant improvement in patient satisfaction with the care provided by the facility.

12. Feedback

• Patients should be able to provide honest feedback, which should be taken into consideration

To provide patient-centred care, patients should have the opportunity to give meaningful feedback without the perception of penalty. Various methods are available to the facility including surveys and questionnaires. Patient surveys should cover the entirety of the patient experience, and may be modified over time to assess the impact of changes made to the service.

To reach levels B and A, the facility should respond to any concerns that patients have raised and should assess the effectiveness of changes made. A policy on the handling of patient complaints should be in place to ensure they are addressed in a standardized fashion and to ensure that staff and endoscopists are treated fairly via a consistent process.

CONCLUSION.

The intended function of the GRS-C is to improve the quality of endoscopic services in Canada by providing a straightforward process for endoscopy facilities to review the quality, safety and patient-centredness of the service they provide. It is focussed on the needs of the patient, not just in terms of the technical quality of the procedure, but also in ensuring that patients receive adequate information and an opportunity to give feedback on their experience.

It is difficult to record and feedback data without proper IT support. The development and use of electronic endoscopy reporting systems to capture data are strongly encouraged. Such systems will be particularly useful for monitoring bookings, recording information about the quality of procedures, and for logging the results of patient surveys. The GRS-C website will provide links to various tools that could be used for these purposes (4).

Cooperation among endoscopy units may provide an efficient solution to help improve endoscopic services. This could include shared use of booking systems to maximize the use of endoscopy resources, including facilities and physicians. Again, the use of information technology would greatly facilitate this cooperation.

It is hoped that increased use of the GRS-C could help to improve endoscopic services in Canada, as it has in the UK (5). Use of the survey will encourage improved record keeping, identify potential problems within units, and encourage patient feedback and a focus on patient-centred care. These are fundamental to the provision of high-quality endoscopy services. Regular review processes should help to address any potential problems raised by patients or identified in the records. By systematically assessing any improvements that are implemented to address these problems, endoscopy units will be able to adapt their processes to suit their own needs and the needs of the patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the mentorship provided by Dr Roland Valori. This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr George Ghattas.

APPENDIX 1

| Dimension: | Clinical Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 1. Consent Process including Patient Information | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 1.1 | There is a published patient information sheet, available in written and/or electronic form, for each endoscopic procedure performed in the facility. This sheet describes the procedure, risks, expected benefits, available alternatives and preparation for the procedure. | Y / N | D |

| 1.2 | Patient information sheets are provided to the patient before the patient comes to the facility or starts any procedure-related intervention (e.g. bowel preparation, stopping anticoagulants). | Y / N | D |

| 1.3 | There is a consent policy for endoscopic procedures available in written and/or electronic form. This policy should include elements such as consent is secured by the endoscopist and who signs the consent form for incompetent patients. | Y / N | D |

| 1.4 | On the day of the procedure, patients are given the opportunity to ask questions before entering the procedure room. | Y / N | C |

| 1.5 | Patient satisfaction surveys, which include questions regarding the patient’s experience with the consent process, are performed at least once per year. | Y / N | C |

| 1.6 | Patient satisfaction surveys, which include questions regarding the quality of patient information provided, are performed at least once per year. | Y / N | C |

| 1.7 | The facility makes changes within three months to the consent process when suggested by patient satisfaction surveys. | Y / N | B |

| 1.8 | The facility makes changes within three months to patient information sheets when suggested by patient satisfaction surveys. Changes should incorporate patient frequently asked questions. | Y / N | B |

| 1.9 | The facility reviews the impact of changes made to the consent process in the subsequent annual survey. | Y / N | A |

| 1.10 | The facility reviews the impact of changes made to patient information in the subsequent annual survey. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Clinical Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 2. Safety | ||

| A key safety indicator refers to a measure with a predefined standard such as colonoscopy perforation rate of <1:1,000. An auditable outcome is a measure for which no recommended standard is defined, such as perforation during diagnostic endoscopy. Usually there will be an evidence base to support a standard for a safety indicator, but not an auditable outcome. A facility may wish to attach a standard for one of its auditable outcomes, whereupon it would become a safety indicator. | |||

| Achieved (Yes/No) | Level | ||

| 2.1 | The facility has a system for recording endoscopy-related adverse events. | Y / N | D |

| 2.2 | Safety indicators and auditable outcomes recorded by the facility, as recommended by the CAG, are available in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | D |

| 2.3 | The facility has a disinfection policy. | Y / N | D |

| 2.4 | A responsible committee reviews adverse events at least twice a year. | Y / N | C |

| 2.5 | Endoscopists are given feedback on their individual safety review at least twice a year. | Y / N | C |

| 2.6 | Auditable outcomes for disinfection are monitored. | Y / N | C |

| 2.7 | The facility has a system for identifying and reviewing adverse events that occur within 14 days of an endoscopic procedure including in-hospital deaths and non-elective hospital admissions. | Y / N | B |

| 2.8 | Actions on safety indicators and auditable outcomes are implemented within three months of review. | Y / N | B |

| 2.9 | Action is taken if auditable outcomes for disinfection are not achieved. | Y / N | B |

| 2.10 | The facility takes action within three months if agreed targets for safety indicators and auditable outcomes are not achieved. | Y / N | A |

| 2.11 | Endoscopists who fail to achieve satisfactory performance (defined by auditable outcomes) after an agreed amount of time will have their practice reviewed by a responsible committee. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Clinical Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 3. Comfort | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 3.1 | There is basic monitoring of patient comfort. | Y / N | D |

| 3.2 | The patient is given realistic expectation that some discomfort may be experienced during the procedure. | Y / N | D |

| 3.3 | Nurses monitor and record patient pain and comfort during and after the procedure. | Y / N | C |

| 3.4 | Unacceptable comfort levels prompt a review during the procedure. This review includes the technique, sedation level and indication for the procedure. | Y / N | C |

| 3.5 | Patient surveys about comfort are performed at least once per year. | Y / N | C |

| 3.6 | Monitoring of patient comfort (surveys and nurse records) is reviewed at least twice a year. | Y / N | B |

| 3.7 | Anonymised data on patient comfort is fed back to individual endoscopists and the endoscopy team at least twice a year. | Y / N | B |

| 3.8 | Action is taken if patient comfort levels fall below agreed levels. | Y / N | B |

| 3.9 | Action on patient comfort is reviewed within six months to ensure issues have been dealt with. | Y / N | A |

| 3.10 | If patient comfort scores do not reach acceptable levels after three months following review of practice, the facility endoscopy or risk management committee reviews that individual’s practice. (Tick yes if comfort levels acceptable for all endoscopists) | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Clinical Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 4. Quality of the Procedure | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 4.1 | The facility has a system for recording endoscopy-related quality indicators. | Y / N | D |

| 4.2 | The quality indicators and auditable outcomes recorded by the facility, as recommended by the CAG, are available in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | D |

| 4.3 | Routine practice audits and/or chart reviews on outcomes and quality of procedures (such as quality of bowel preparation, success and adherence to guidelines for management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeds, and rate of successful bile duct cannulation) are performed annually. | Y / N | C |

| 4.4 | A responsible committee reviews procedure quality indicators and auditable outcomes at least twice a year. | Y / N | C |

| 4.5 | Endoscopists are given feedback on their individual quality indicator outcomes at least twice a year. | Y / N | C |

| 4.6 | A plan of action including goals and timescale is agreed to with an individual endoscopist in response to performance that does not meet defined standards. | Y / N | B |

| 4.7 | The facility uses an electronic endoscopy reporting system to record and analyze endoscopic quality indicators and auditable outcomes. | Y / N | B |

| 4.8 | Action is taken in response to failure to achieve previously defined performance standards within agreed time scale. | Y / N | A |

| 4.9 | Endoscopists who do not achieve standards and benchmarks after agreed time will have their practice reviewed by a responsible committee. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Clinical Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 5. Appropriateness | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 5.1 | Established guidelines for screening and surveillance endoscopy are available in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | D |

| 5.2 | Surveillance and screening endoscopy is booked according to established guidelines. | Y / N | D |

| 5.3 | If the facility offers direct-to-procedure endoscopy, there are local guidelines for referring physicians available in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | C |

| 5.4 | The facility performs annual audits of adherence to established screening and surveillance guidelines. | Y / N | C |

| 5.5 | Endoscopists are notified of the results of annual appropriateness audits. | Y / N | C |

| 5.6 | There is an annual review of the direct-to-procedure guidelines and referral process. | Y / N | C |

| 5.7 | The facility responds with action plans within three months if problems are identified by audits of screening and surveillance procedures. | Y / N | B |

| 5.8 | The facility makes changes to direct-to-procedure referral process suggested by annual review. | Y / N | B |

| 5.9 | The facility reviews the effect of changes made to screening and surveillance procedures, within three months of the survey analysis. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Clinical Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 6. Communicating Results | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 6.1 | Endoscopy reports are completed the same day as the procedure. | Y / N | D |

| 6.2 | Results of inpatient procedures are placed in the chart prior to the patient’s departure from the unit. | Y / N | D |

| 6.3 | The facility has a policy listing standardized elements of an endoscopy report, as recommended by the CAG, which are required in the report. | Y / N | C |

| 6.4 | All endoscopy reports are submitted to the referring physician within five working days of the procedure. | Y / N | C |

| 6.5 | A copy of the pathology report is sent to the endoscopist and referring physician. | Y / N | C |

| 6.6 | The facility performs annual audits of endoscopist adherence to standardized endoscopy reports. The results are submitted as part of performance reports. | Y / N | C |

| 6.7 | The endoscopist is responsible for ensuring that pathology results are conveyed to the patient. | Y / N | C |

| 6.8 | The facility uses an electronic endoscopy reporting system. | Y / N | B |

| 6.9 | The facility responds with action plans within three months to endoscopy report audits if problems are identified. | Y / N | B |

| 6.10 | Actions taken in response to endoscopy report audits are reviewed within three months. | Y / N | A |

| 6.11 | All endoscopy reports are submitted to the referring physician within one working day of the procedure. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Quality of Patient Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 7. Equality of Access | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 7.1 | Practices of the facility reflect the equality of access and diversity policy of the institution. | Y / N | D |

| 7.2 | Communication needs are recorded as part of the nursing assessment. | Y / N | D |

| 7.3 | All patients are offered interpreter/translator if needed. | Y / N | C |

| 7.4 | A demographic/language profile of the local population (needs assessment) is available. | Y / N | C |

| 7.5 | Facility and procedure information is available in written and/or electronic form in the most prevalent community languages, as determined by needs assessment. | Y / N | C |

| 7.6 | The facility elicits feedback regarding equality of access, language and accessibility by the annual patient satisfaction survey. | Y / N | C |

| 7.7 | The facility responds with action plans within three months to feedback and surveys if problems are identified regarding equality of access. | Y / N | B |

| 7.8 | The facility reviews the effect of changes made to correct problems of equality of access within three months. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Quality of Patient Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 8. Timeliness | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 8.1 | The facility uses the CAG wait list criteria for classification of endoscopy referrals into urgent, semi-urgent, routine and surveillance categories. These criteria are available in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | D |

| 8.2 | The facility has a system to measure wait times for urgent, semi-urgent, routine and surveillance procedures. | Y / N | D |

| 8.3 | The facility records wait times for urgent, semi-urgent and routine procedures and documents adherence to the CAG wait list criteria. | Y / N | C |

| 8.4 | Endoscopy wait times are communicated to the endoscopy team monthly and are made available to referring physicians in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | C |

| 8.5 | Waits for urgent procedures are less than six weeks from referral. | Y / N | C |

| 8.6 | The facility makes changes to reduce wait times that exceed the CAG wait list criteria. | Y / N | B |

| 8.7 | There is some pooling of endoscopy lists. | Y / N | B |

| 8.8 | Waits for urgent procedures are less than four weeks from referral. | Y / N | B |

| 8.9 | Waits for urgent procedures are less than two weeks from referral. | Y / N | A |

| 8.10 | Capacity can be changed to accommodate urgent and semi-urgent procedures. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Quality of Patient Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 9. Booking and Choice | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 9.1 | Patients are informed of their appointment by letter, phone or fax. | Y / N | D |

| 9.2 | Co-morbidities such as diabetes and anti-coagulation are accounted for in the scheduling of appointments. | Y / N | D |

| 9.3 | No-show and cancellation rates are monitored. | Y / N | C |

| 9.4 | Referring physicians are notified when patients miss appointments. | Y / N | C |

| 9.5 | Patients receive a reminder phone call within one week of their appointment. | Y / N | C |

| 9.6 | The facility elicits feedback regarding the booking process by the annual patient satisfaction survey. | Y / N | C |

| 9.7 | The facility responds with action plans within three months to feedback and surveys of the booking process if problems are identified. | Y / N | B |

| 9.8 | The facility responds to higher than 5% no-show or cancellation rates. | Y / N | B |

| 9.9 | Patients are given a choice about the date and time of day of their appointment. | Y / N | B |

| 9.10 | The facility reviews the effect of changes made to correct problems of booking within three months. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Quality of Patient Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 10. Privacy and Dignity | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 10.1 | The facility has screens/curtains to provide privacy pre and post procedure. | Y / N | D |

| 10.2 | The facility has a dedicated recovery room area. | Y / N | D |

| 10.3 | The facility provides a secure individual space for patients to keep belongings. | Y / N | D |

| 10.4 | The facility provides readily accessible patient toilet and wash facilities. | Y / N | D |

| 10.5 | The facility has a quiet room for conversation beyond the hearing of others. | Y / N | C |

| 10.6 | The facility elicits feedback regarding privacy and dignity by the annual patient satisfaction survey. | Y / N | C |

| 10.7 | The facility responds with action plans within three months to feedback and surveys of privacy and dignity if problems are identified. | Y / N | B |

| 10.8 | Patients are asked if they wish to discuss procedure results and clinical care in private. | Y / N | B |

| 10.9 | The facility reviews the effect of changes made to correct problems of privacy and dignity within three months. | Y / N | A |

| 10.10 | The recovery area is separate from the pre-procedure patient waiting area. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Quality of Patient Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 11. Aftercare | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 11.1 | The facility provides a contact number post-procedure for questions or problems. | Y / N | D |

| 11.2 | It is policy that all patients who have received sedation are accompanied by an adult when leaving the facility. | Y / N | D |

| 11.3 | Discharge instructions for all procedures are provided to the patient before leaving the facility. | Y / N | C |

| 11.4 | The facility provides a 24-hour contact number post-procedure for questions or problems. | Y / N | C |

| 11.5 | All patients are told if biopsies were taken during the procedure and who will provide the results. | Y / N | C |

| 11.6 | All patients are told the result of their procedure before leaving the facility. | Y / N | C |

| 11.7 | The facility elicits feedback regarding aftercare by the annual patient satisfaction survey. | Y / N | C |

| 11.8 | The facility responds with action plans within three months to feedback and surveys of aftercare if problems are identified. | Y / N | B |

| 11.9 | The patient receives a copy of the endoscopy report or a patient version, including a summary of findings and planned follow up, before leaving the facility. | Y / N | B |

| 11.10 | The endoscopist communicates to the patient specifically who is responsible for arranging follow up appointments. | Y / N | B |

| 11.11 | The facility reviews the effect of changes made to correct problems of aftercare within three months. | Y / N | A |

| Dimension: | Quality of Patient Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item: | 12. Ability to provide feedback | Achieved (Yes/No) | Level |

| 12.1 | The facility has a system for gathering patient feedback such as satisfaction surveys, focus groups, or invited comments. | Y / N | D |

| 12.2 | The facility has a policy for patient complaints that is available in written and/or electronic form. | Y / N | D |

| 12.3 | Action is planned (with auditable outcomes) in response to patient complaints. | Y / N | C |

| 12.4 | The facility has a person or committee responsible for reviewing complaints. | Y / N | C |

| 12.5 | Patient feedback is sought and reviewed annually. | Y / N | C |

| 12.6 | The facility responds within three months with action plans based upon reviews of patient feedback if problems are identified. | Y / N | B |

| 12.7 | The facility reviews the effect of changes made in response to patient feedback within three months. | Y / N | A |

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/STUDY SUPPORT: No industry or government relationships to report: D MacIntosh, C Dubé, R Hollingworth, S Veldhuyzen van Zanten, S Daniels, G Ghattas. Writing support was provided by Rosalind Morley at PharmaGenesisTM London.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, Swarbrick E, Williams CB, Epstein O. A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: Are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut. 2004;53:277–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong D, Barkun AN, Chen Y, et al. Access to specialist gastroenterology care in Canada: The Practice Audit in Gastroenterology (PAGE) Wait Times Program. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:155–60. doi: 10.1155/2008/292948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Advisory Group Global Rating Scale. < www.jagaccreditation.org/> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 4.Global Rating Scale < www.globalratingscale.com/> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 5.Valori RM, Barton R, Johnston DK. The English National Endoscopy Quality Assurance Programme: Quality of care improves as waits decline. Gastrointestinal Endosc. 2009;69:AB221. (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health, 2002–03. < www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/jcush_analyticalreport.pdf> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 7.Statistics Canada Access to Health Care Services in Canada. January to December 2005. < www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-575-x/82-575-x2006002-eng.pdf> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 8.Paterson WG, Depew WT, Paré P, et al. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:411–23. doi: 10.1155/2006/343686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong D, Hollingworth R, Macintosh D, et al. Point-of-care, peer-comparator colonoscopy practice audit: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Quality Program – Endoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:13–20. doi: 10.1155/2011/320904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jonge V, Sint Nicolaas J, Lalor EA, et al. A prospective audit of patient experiences in colonoscopy using the Global Rating Scale: A cohort of 1187 patients. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:607–13. doi: 10.1155/2010/724924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong D, Barkun A, Bridges R, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on safety and quality indicators in endoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:17–31. doi: 10.1155/2012/173739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leddin D, Armstrong D, Barkun AN, et al. Access to specialist gastroenterology care in Canada: Comparison of wait times and consensus targets. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:161–7. doi: 10.1155/2008/479684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GRS Canada < www.mdpub.org/grs/> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 14.MacSween HM. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Practice Guideline for informed consent – gastrointestinal endoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997;11:533–4. doi: 10.1155/1997/976472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgaonkar MR, Hookey L, Hollingworth R, et al. Indicators of safety compromise in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:71–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/782790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross E, Dube C, Hilsden RJ, et al. Development and prospective evaluation of a nurse assessed patient comfort scale (NAPCOMS) for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.003. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enns R. Quality indicators in colonoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:277–9. doi: 10.1155/2007/582062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: The European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378–84. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint Advisory Group Training for Endoscopists. < www.thejag.org.uk/TrainingforEndoscopists.aspx> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 22.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: A consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Commission European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. 2011. < http://bookshop.europa.eu/is-bin/INTERSHOP.enfinity/WFS/EU-Bookshop-Site/en_GB/-/EUR/ViewPublication-Start?PublicationKey=ND3210390> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 24.Froehlich F, Repond C, Müllhaupt B, et al. Is the diagnostic yield of upper GI endoscopy improved by the use of explicit panel-based appropriateness criteria? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:333–41. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.107906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quine MA, Bell GD, McCloy RF, Devlin HB, Hopkins A. Appropriate use of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy – a prospective audit. Steering Group of the Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Audit Committee. Gut. 1994;35:1209–14. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.9.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John BJ, Irukulla S, Pilgrim G, Swift I, Abulafi AM. Surveillance colonoscopies for colorectal polyps – too often, too many! An audit at a large district general hospital. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:898–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mysliwiec PA, Brown ML, Klabunde CN, Ransohoff DF. Are physicians doing too much colonoscopy? A national survey of colorectal surveillance after polypectomy. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:264–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saini SD, Nayak RS, Kuhn L, Schoenfeld P. Why don’t gastroenterologists follow colon polyp surveillance guidelines?: Results of a national survey. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:554–8. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818242ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Kooten H, de Jonge V, Schreuders E, et al. Awareness of postpolypectomy surveillance guidelines: A nationwide survey of colonoscopists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:79–84. doi: 10.1155/2012/919615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreuders E, Sint Nicolaas J, van Kooten H, et al. The appropriateness of colonoscopy surveillance intervals after polypectomy. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S-1-1062. doi: 10.1155/2013/279897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leddin D, Hunt R, Champion M, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation: Guidelines on colon cancer screening. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:93–9. doi: 10.1155/2004/983459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002) Gut. 2010;59:666–89. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.179804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Gastroenterological Association Polyp Surveillance Measures. < www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/performance-measures/polyp-surveillance> (Accessed October 5, 2012).

- 35.Sewitch MJ, Gong S, Dube C, Barkun A, Hilsden R, Armstrong D. A literature review of quality in lower gastrointestinal endoscopy from the patient perspective. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:681–5. doi: 10.1155/2011/590356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macintosh D, MacDonald E, Gruchy S. An audit of quality indicators in colonoscopy reports using an electronic reporting system with mandatory data fields. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(Suppl A):141A. (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sewitch MJ, Barkun AN. Fighting colorectal cancer with information technology. CMAJ. 2011;183:1053–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111-2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]