1 Introduction

Immune responses to tumor antigens are seen in almost all cancers but, since growth is usually progressive, are clearly ineffective in elimination of the tumor (Parmiani et al., 2003). Understanding the biochemical basis for escape from anti-tumor immunity guides multiple avenues of research endeavor. Failure to eliminate tumors can be potentially explained by a variety of reasons, any or all of which may permit escape from immune-mediated eradication (Rabinovich et al., 2007). The possibilities can be broadly grouped into two categories: inhibition of the antitumor priming phase or inhibition of the effector phase. Antitumor Ig and T cells are found in patients and in animal models proving that some measurable priming occurs during tumor growth (Frey and Monu, 2006; Radoja et al., 2000). That the magnitude of a given antitumor response is clearly less robust in comparison to that detected after microbial infection (where, for example, up to 10 % of circulating T cells can be reactive with Epstein–Barr virus proteins) has been interpreted to mean that tumors grow faster than the immune response can contend with. This notion is overly simplistic since human tumors grow quite slowly and there is clearly inhibition of both expansion in number and function of anti-tumor T cells (see below). The notion that priming of antitumor T cells is defi-cient during tumor growth is supported by findings that the frequency of tumor-specific T cells can be considerably increased in patients receiving experimental immunotherapy. Unfortunately, in spite of greater numbers of antitumor effector T cells in the blood of vaccinated patients (that secrete IFN-γ in response to recognition of cognate antigen in vitro), tumors are often not eliminated (Rosenberg et al., 2004). This observation suggests that experimental vaccination in human cancer is imperfect/inadequate, a reasonable interpretation considering the advanced state of disease which patients must demonstrate in order to qualify for experimental therapy and which motivates the pursuit of better candidate vaccines. Alternatively there may be immunesuppression and/or immune tolerance in the tumor microenviron-ment, the draining LN or systemically which impedes the function of the antitumor T cells induced by vaccination, also a reasonable interpretation (Frey and Monu, 2006).

Antigen-specific tolerance to tumor antigens can be induced by tumor growth (Cuenca et al., 2003; Lee et al., 1999; Overwijk et al., 2003; Willimsky and Blankenstein, 2005) and, since many tumor antigens have been shown to be self-derived differentiation antigens, has focused much attention on attempts to overcome anergy (Pardoll, 2003). The anergic phenotype of antitumor T cells is complex: adoptive transfer of naive T cells reactive to a model xenogenic tumor antigen could expand in tumor-bearing mice implying priming in vivo (Staveley-O’Carroll et al., 1998). However, the T cells did not respond to subsequent in vivo vaccination, a finding that was interpreted to mean that initial encounter with antigen induces anergy. Induced anergy is not a function of T-cell differentiation status since similar results using memory or effector T cells in adoptive transfer protocols have been reported (Horna et al., 2006). A prominent role for CD4+CD25+ TReg in anergy induction following vaccination has been shown (Gattinoni et al., 2006) and abundant TReg are found in some tumors (Curiel et al., 2004), inspiring efforts that attempt to either eliminate or block TReg activity concurrent with vaccination (Zou, 2005).

Although prominent, the role of TReg in causing antitumor T-cell dysfunction in vivo is possibly not exclusive since considerable antigen-specific cells are found not activated in situ (Zhou et al., 2006). This observation supports the notion that dendritic cell function (antigen processing and/or cell activation) is likely to be deficient, a topic both recently reviewed (Bronte et al., 2006; Gabrilovich, 2004) and vigorously pursued. Another observation suggestive that priming is defective in tumor-bearing hosts is that several HLA Class I-restricted tumor antigens have been identified (using antitumor TIL as the basis of tumor cDNA expression systems) that are products of tumor-specific mishandling of genetic information—faulty mRNA transcription, splicing or translation (Coulie et al., 1995; Dolcetti et al., 1999; Guilloux et al., 1996; Ishikawa et al., 2003; Lupetti et al., 1998). Originally proposed by T. Boon in 1989 (Boon and Van Pel, 1989), to considerable skepticism (Lindahl, 1991), these antigens are expressed from alternative reading frames or intronic sequences. Clearly these antigens are not “self” and their cognate TCR are therefore likely to be of relatively high affinity. Thus, those T cells probably are not subject to the regulatory constraints imposed by the clonal selection theory on self-reactive T cells in the periphery whose TCR affinity for cognate antigen is modest. Although not directly assessed, the abundance of this class of antitumor T cell is probably low in situ which implies either that the precursor frequency is low or priming of the cognate T cells is deficient. (Their effector-phase functions are also clearly suppressed since tumors grow, implying a second level of defect, discussed in detail below. However, two reports showed enhanced death of cancer cells proximal to CD8+ T cells in tumors having increased microsatellite instability encouraging the notion that antitumor TIL in situ can in some cases express lytic function (Dolcetti et al., 1999; Ishikawa et al., 2003).)

Evidence for defective T-cell priming in tumor-bearing hosts is abundant and it undoubtedly contributes to modest (or failed) antitumor T-cell immune response (discussed in other chapters); nevertheless, since there is demonstrable antitumor immune responses some priming must occur. Antitumor T cells are found in patient blood, LN and tumor tissue but are defective in response to stimulation through the TCR: cytokine release, lytic function and proliferation are often deficient (Whiteside and Parmiani, 1994); the extent of deficiency is dependent upon tumor type and stage, and the type of assay employed. These defects may be explained by several potential mechanisms that can be generalized as (1) the absence of a positive activation signal, i.e., antigen (or costimulation) or (2) the presence of a negative signal, i.e., enhanced (and dominant) activity of an inhibitory signaling receptor or soluble mediator (e.g., PD-1 or TGFβ-1). This latter notion is reminiscent of the phenotype of T cells in response to agonist plus antagonist peptides, or perhaps only partial agonist peptide (Sloan-Lancaster et al., 1996; Sloan-Lancaster et al., 1996).

There is clearly tumor antigen present in the body, since tumors are usually clinically discernible, thus the absence of antigen is not the basis for the non-activated state of antitumor T cells (although processing and presentation by dendritic cells may be impaired). Also, deficient costimulation (by APC) possibly contributes to the limited magnitude of priming. Therefore, albeit not maximally expanded in number, antitumor T cells in the circulation and tumor tissue have suppressed immune responses likely due to some form of inhibition. This review analyzes the data concerning tumor-induced inhibition of antitumor T-cell function.

2 Systemic Defects in Antitumor T-Cell Function

The observation that patients with late-stage cancers can have defective systemic DTH and proliferative T-cell responses, and diminished (or skewed) cytokine production (Stutman, 1975), prompted biochemical analyses of signaling in peripheral and tumor-infiltrating T cells (reviewed in Whiteside and Parmiani, 1994). The subject has been vigorously pursued in both animal models and patients and there is general acceptance of the notion that tumor antigen-specific proliferative responses and cytokine production from PBL (and in splenocytes in rodent models) are defi-cient and that the magnitude of defects expands as tumor burden increases (Wick et al., 1997). One of the pioneering publications which strove to provide a biochemical basis for defective immunity in tumor-bearing hosts reported analysis of in vivo and in vitro lytic function of spleen-derived, IL-2 plus anti-CD3ε-activated killer cells from mice bearing tumors (Loeffler et al., 1992). Loeffler and colleagues showed a decrease in cytolysis if total spleen T cells were analyzed from mice bearing tumors grown for more than 21 days, implying a tumor-induced defect in the development of lytic potential. The precise nature of the lytic cells assayed cannot be readily determined since the enriched T cells were cultured in IL-2 for an indeterminate time period in vitro before use, and lytic function was not totally abrogated, only severely reduced in comparison to cells originally obtained from control mice. Curiously, production of several cytokines from enriched T cells activated in vitro was enhanced compared to control cells implying that T cells could be activated in vitro, and stated (but not shown) was that proliferation of CD4+ cells in vitro was normal. Conditioned medium from the tumor cells (MCA38, a colon adenocarcinoma) partially blocked the in vitro development of lytic activity in control killer cells and granzyme B and TNF RNA levels were decreased (although protein levels were not quantified and RNA levels for IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-6 were unchanged). That observation was interpreted to mean that tumor growth could cause enhanced degradation or inhibition of transcription of mRNAs encoding selected effector-phase proteins, thus explaining lytic T-cell dysfunction. This paper also suggested that tumor cells secrete a factor(s) that impacts negatively on the development of lytic function in T cells, although further work on that factor has not been published.

Following closely the initial description of a tumor-elaborated factor, which presumptively inhibited development of T-cell lytic function in tumor-bearing mice, a paper was published in which unmanipulated purified spleen T cells of tumor-bearing mice were analyzed for both calcium flux in vitro and levels of some components of the proximal TCR signaling complex (Mizoguchi et al., 1992). Calcium flux was reduced (~30 %) in T cells from tumor-bearing mice after stimulation with anti-CD3ε Ab implying defective TCR-mediated signaling. (Stimulation of T cells with cognate tumor cells was not performed, a technical necessity later shown to dramatically impact upon signaling in antitumor T cells (Koneru et al., 2005).) Stated (but not shown) was that activation of cells with calcium ionophore resulted in normal levels of calcium flux implying that the signaling block was in the proximal TCR pathway. Assessment of total protein tyrosine phosphorylation by immunoblotting of non-ionic detergent cell extracts from in vitro activated T cells showed a dramatic reduction in tyrosine kinase activity. Immunoblotting further showed absent p56lck and p59fyn, the two tyrosine kinases most proximal in the TCR signaling cascade (see below). Finally, in order to characterize the structural composition of the TCR, T cells were surface labeled by lactoperoxidase-catalyzed iodination, solubilized with non-ionic detergent, immuneprecipitated with anti-CD3ε and radi-olabeled proteins that associated with CD3ε were analyzed by electrophoresis and blotting. TCRζ, an adapter protein that is the target of p56lck (see below) which when phosphorylated recruits ZAP70 permitting activation of downstream signaling pathways, was determined to be absent from the TCR complex in T cells isolated from tumor-bearing mice. Further, and perhaps most surprising, the FcR γ chain normally found associated with CD16 in non-CD8+ T cells (NKT cells, granulocytes, myeloid cells, γδT cells and NK cells (Ravetch and Kinet, 1991)) was robustly detected in T cells isolated from tumor-bearing but not control mice. Stated, but not shown, was that other aspects of activation in vitro were normal (proliferation, secretion of cytokines and IL-2R upregulation) implying that the T-cell deficit is primarily limited to cytolytic function, a concept since termed “split anergy” (Mescher et al., 2006), although lytic function of T cells was not assessed. (Expression of FcR γ chain “in exchange” for TCRζ in CD8+ T cells has not been subsequently reported.)

Several aspects of this work bear reflection. Most importantly, this paper ushered to the forefront an important biochemical perspective on the study of immune dysfunction in cancer: the notion that structural or functional defects in components of the proximal TCR signaling machinery are caused by tumor growth and that these defects underlie the defective functional phenotype of T cells in cancer therein permitting growth of antigenic tumor. However, perhaps because of the enduring effect this work has had on motivating subsequent years of research in multiple laboratories, some of the original findings and interpretations can be critically re-evaluated. Crucial is the contradiction that T cells lacking both p59fyn and p56lck can transmit any activation signal when CD3ε is crosslinked by Ab in vitro: if T cells had normal cytokine secretion, upregulation of IL-2R and proliferation, as stated by Mizoguchi and colleagues, these cells must have functional proximal TCR machinery in order to have transmitted an activation signal. That granted, the apparent absence of both proximal kinases (p59fyn and p56lck) and TCRζ, assessed after detergent solubilization and immunoblotting (with or without immuneprecipitation or in later publications by flow cytometry of complex mixtures of cells, e.g., Whiteside, 2004), is likely a false-negative finding. This supposition is supported by the authors’ data that calcium flux is intact in T cells from tumor-bearing mice, albeit diminished compared to controls. Collectively considered, one interpretation of those results is that biochemical and functional assay of signaling in T cells before permeabilization is correct (diminished calcium flux, sometimes depressed cytokine secretion, proliferation) and that apparent loss of selected signaling components (p56lck, TCRζ) reflects artifactual degradation of protein attendant to cell lysis conditions. This notion is supported by subsequent results from multiple laboratories that showed TCRζ is particularly sensitive to proteolysis (Bronte et al., 2005; Franco et al., 1995; Gastman et al., 1999; Levey and Srivastava, 1995; Wang et al., 1995).

This conclusion can also be drawn from a subsequent paper from that lab in which the kinetics of loss of TCRζ and p56lck as a function of time of tumor growth was determined (Correa et al., 1997). In contrast to previous publications where TCRζ was “missing” from peripheral T cells after 21 days of tumor growth, Correa et al. showed TCRζ loss only after ~32 days of growth. However, p56lck was found absent at much earlier times of growth (ca. 18 days) raising several questions: first, what is the basis for the disparate results concerning the kinetics of TCRζ loss? The loss of a component of the TCR complex most proximal in the cascade probably is causal to any additional effects on downstream components, so the basis for the most proximal defect should be the primary focus. The focus on the apparent loss of TCRζ, which is downstream of p56lck in the signaling machinery, was not explained. In any event, levels of cytokine secretion in vitro from “late-stage” tumor-bearing mouse T cells after TCR ligation were found to be either diminished (IL-2, IFN-γ) or enhanced (IL-4, IL-10) relative to control T cells, again arguing that T cells could receive and respond to external signals. Importantly, when T cells were lysed under “harsh conditions” (boiling in SDS) TCRζ levels were approximately equal to control samples (p56lck levels were not assessed under harsh lysis conditions). This finding was interpreted to mean the TCRζ localizes to a subcel-lular compartment that is resistant to non-ionic detergent solubilization in T cells of late-stage tumor-bearing mice. Immunocytochemistry or immunofluorescence microscopy localization of TCRζ, which would validate that notion, was not performed.

Considered in light of multiple publications that show downregulation of proximal TCR signaling molecules as a normal consequence of antigen recognition (Marth et al., 1987; Olszowy et al., 1995; Valitutti et al., 1997; Veillette et al., 1988), it seems possible that the observed changes in levels of p56lck and TCRζ may reflect normal physiological variation after antigen recognition. Furthermore, the consequences to the host of absent proximal TCR signaling in peripheral T cells are expected to be dramatic in that responses to environmental pathogens would be obviated. That would result in systemic pathology akin to acquired immunodefi-ciency, a condition not seen in rodent models or patients. In addition, using the same tumor model as used in the original findings (MCA38), among multiple other tumor models, our lab showed that mice bearing comparatively large tumors had both normal immune responses to various soluble and cellular antigens in vivo and normal in vitro responses to stimulation if the responding T cells were sufficiently purified. These data argue that there is no systemic T-cell dysfunction in tumor-bearing mice (Radoja et al., 2000). Finally, there have been reports that TCRζ levels are not sig-nificantly reduced in either PBL or TIL in renal cell carcinoma (Cardi et al., 1997) or in TIL (in frozen thin sections) in Hodgkin’s disease (Dukers et al., 2000) arguing against this notion. Despite the concerns that these data illustrate in consideration of the biochemical basis of systemic T-cell dysfunction caused by tumor growth, tumor-induced defective antitumor-specific immune response is probably common in cancer and is causally related to tumor escape from immune response (Cochran et al., 2006; Shu et al., 2006).

We feel that close attention devoted to the issue of TCRζ levels in systemic or tumor-infiltrating T cells is warranted because, since the original findings made in rodent models, in an effort to determine the basis of dysfunctional antitumor immune responses in patients, other laboratories have published similar findings in patient PBL (Whiteside, 2004) or TIL (Uzzo et al., 1999b), whose conclusions may similarly justify re-evaluation.

3 Defective Proliferation of Peripheral Blood T Cells in Cancer Patients

The year following the original reports of TCRζ loss in systemic T cells in rodent models, two papers were published which described similar observations in human TIL and PBL (Finke et al., 1993; Nakagomi et al., 1993). Proliferation of T cells in vitro was found to be deficient in TIL and PBL isolated from patients with various types of cancers, in much the same manner as was previously determined for spleen cells in rodent models. Typically mononuclear cells were isolated from blood by density gradient fractionation and stimulated with mitogen or anti-CD3ε. In some cases cytokine secretion was also determined to be decreased in comparison to non-stimulated patient PBL. Where analyzed in historical comparison, defective in vitro responses of TIL are usually more pronounced than for PBL (Alexander et al., 1993; Whiteside and Parmiani, 1994). These sorts of data have been interpreted to mean that systemic T-cell immunity is compromised in cancer patients that may reflect tumor-induced immune suppression. The basis of patient defective proliferative response has been pursued and is considered herein.

To concerns about similar experiments using rodent cells (Radoja et al., 2000), we suggest that interpretation of these data be tempered by several caveats. If the patient PBL preparations are not purified they possibly are contaminated by blood cells that have been shown to inhibit T-cell proliferation or cause apoptosis of activated cells in vitro (Schmielau and Finn, 2001). Additional concerns are that proliferation of patient PBL in vitro in some cases was not calculated as a percentage of CD3+ cells within the population and is also not extinguished, rather; the percentage increase in proliferation of patient PBL is diminished relative to PBL from control non-patients (Whiteside, 2004). Absolute levels of incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine per cell is sometimes not revealed nor is non-patient PBL always used in comparison (Reichert et al., 2002) making assessment of results between different labs and tumor types impossible. In addition, the percentage of individual patients within a cohort with diminished responses is sometimes not provided making the “penetrance” of the phenomenon among the larger patient population difficult to establish.

One early paper showed significant inhibition of renal cell carcinoma TIL in vitro proliferation but, curiously, autologous PBL were not affected (Alexander et al., 1993). Four years later the same lab published that culture supernatant from a renal cell cancer cell line could dramatically inhibit proliferation in vitro of normal T cells (Kolenko et al., 1997). Biochemical analysis showed that while p56lck and TCRζ levels were normal, T-cell levels of IL-2R-associated kinase JAK3 were dramatically reduced. (Over the years additional publications from that lab deemphasized TCRζ loss from T cells or found the majority of patient PBL to have normal levels (Bukowski et al., 1998), instead focusing on other systemic signaling defects induced by factors released from tumor cells which appear to induce a “pre-apoptotic state” in TIL or PBL, see below. Further reports of a role for JAK3 in systemic T-cell defects have not been published.)

4 Enhanced Sensitivity to AICD in Systemic T Cells in Cancer Patients Due To Tumor Secretion of Gangliosides

Over the years there have been many reports of antiproliferative or proapoptotic activities in supernatants of tumor cell cultures which induce T-cell apoptosis in vitro including, but not limited to: TGFζ, IL-10, PGE and soluble reactive oxygen and nitrogen molecules. In at least one type of cancer, glioma patients are known to be lymphopenic, a condition that could be due to high levels of systemic T-cell apoptosis (Dix et al., 1999). In other cancers, perhaps in early stages of tumor progression, T-cell apoptosis may be initiated and yet not show robust DNA fragmentation, but be nonetheless functionally deficient.

Assessment of the apoptotic status of patient purified PBL T cells determined that a significant percentage of CD3+ PBL T cells are induced to apoptosis after 24 h exposure to anti-Fas or tumor cells (ca. 40 %), or PMA/ionomycin (ca. 22 %, which increases to 80–100 % after 48 h) (Uzzo et al., 1999b). Apoptosis of unstimulated patient T cells was low, as was apoptosis of one control T-cell sample obtained from a non-patient. It was concluded that systemic T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients are in a heightened (or partial) activation state, perhaps due to chronic tumor antigen exposure or to a tumor-elaborated factor(s) (see below). It was hypothesized that if the in vitro phenotype reflected T-cell status in vivo, antigen activation (i.e., strong) would induce AICD in antitumor T cells therein impeding effective antitu-mor immunity in the patient. Heightened sensitivity to AICD in vitro was subsequently shown to be mediated by impairment of activation of NFκB in patient PBL (Li et al., 1994; Uzzo et al., 1999a). Tumor cell culture supernatant contained an activity that induced AICD in Jurkat cells and control PBL upon stimulation that was used as the basis to purify gangliosides, then used in some studies in purified form to study the biochemical basis of the tumor-elaborated activity.

Elevated expression of gangliosides by tumor cells has been long noted (Ladisch et al., 1984); in fact experimental immunotherapy targeting gangliosides has been attempted for many years for several different tumor types (without compelling success) (Blackhall and Shepherd, 2007). Gangliosides can inhibit various immune cells including: maturation of DC (Wolfl et al., 2002), macrophage function (Bennaceur et al., 2006; Bharti and Singh, 2001, 2003), NK cell activity (Ladisch et al., 1984) and cytokine secretion from T cells (Dumontet et al., 1994) and are thought to be shed in exosomes as precursor molecules reflective of alteration of biosyn-thetic enzymes in tumor cells (Hakomori, 1996). Exactly how elevated gangliosides impact on NFκB signaling is not clear: inhibition of activation of the inhibitor IκBα was shown in one report (Ling et al., 1998), but subsequent papers from the same lab suggest IκBα is not involved, instead degradation of NFκB is enhanced (Thornton et al., 2004). It is conceivable that both the biochemical mechanism of action of gangliosides and the nature of the effect on target T cells (e.g., inhibition of cytokine secretion or proliferation, or induction of apoptosis) are concentration dependent. In addition, it is possible that responses to gangliosides are influenced by the nature of activation signals received by the T cell after (or during) ganglioside exposure (Biswas et al., 2006). Therefore, perhaps the contradictory mechanistic data can be reconciled by these considerations.

The details of ganglioside action are likely to be important since the component of the T-cell signaling cascade affected by gangliosides could be a potential point of intervention for immunotherapy. In this regard, a ganglioside receptor in T cells (or any immune cell) has not yet been described which would be a potential target for therapy. However, galectin-1 in a human neuroblastoma cell line was shown in 1998 to be a receptor for GM1 (Kopitz et al., 1998). When expressed in tumor cells, galectins (endogenous lectins, reviewed in Hernandez and Baum, 2002) have been shown to inhibit antitumor T-cell immunity although the mechanism remains unclear. One report showed that exogenous galectin-1 could inhibit full antigen-dependent triggering of T cells (revealed as only partial TCRζ phosphorylation) permitting limited signaling (resulting in expression of CD69, IFN-γ secretion and apoptosis, but not proliferation) (Chung et al., 2000). Exactly how regulation of T-cell signaling by galectins occurs is not clear since proximal signaling appears to be impacted without need for additional cofactors. We introduce this topic only to illustrate by analogy that a cell surface receptor for gangliosides may be expressed on T cells which would help guide our thinking about how exogenous ganglio-sides (presumably tumor-derived) inhibit T-cell signaling: receptor-dependent or receptor-independent. If a ganglioside receptor is expressed on antitumor T cells, then the absolute serum concentration of gangliosides to cause functional inhibition need not be as high as if there were no receptor in order for the concentration to be increased in T cells.

Gangliosides may not require a receptor in order to impact on signaling in T cells. For example, if high concentrations, existing presumably as micelles in the blood or in protein-containing exosomes (although monomeric serum gangliosides have been suggested to exist, Kong et al., 1998), gain proximity to a hydrophobic environment (i.e., the plasma membrane of a T cell), the ganglioside could simply partition into the lipid bilayer for thermodynamic reasons. A question arises here: once fused with the plasma membrane, how would signaling be affected (apparently being reduced as is the phenotype in systemic T cells in patients)? One possibility, yet untested as far as we are aware, is that since the T-cell plasma membrane lipid composition would now be altered by the incorporated gangliosides, formation of the higher order lipid raft upon T-cell activation could be inhibited. Since the TCR complex assembles and is maintained in the lipid raft during activation, the requirements for induction or maintenance of signaling could be adversely affected. Modification of lipid rafts which impact on signal transduction has been reported: in one report exogenous polyunsaturated fatty acids, known to have suppressive effects on signaling in immune cells, were shown to regulate Jurkat cell signaling (Stulnig et al., 1998), and Magee et al. (2005) recently showed that signaling was greatly influenced simply by changing the temperature of the immune cells, which in turn impacted on raft formation. A related notion was postulated by the Ladisch lab who showed that exogenous gangliosides enhanced EGFR aggregation in fibroblasts and resulted in heightened sensitivity to ligand (Liu et al., 2004), paradoxically the obverse phenotype of systemic T cells in cancer patients.

Before gangliosideologists embark on the study of proximal signaling in T cells, considering how many red herrings have been enthusiastically pursued in the past, perhaps it would be prudent to first ascertain the physiological relevance of the notion of ganglioside-influenced T-cell signaling. In doing so the notion of a causal relationship between tumor production of gangliosides and defective T cells in patients would be supported. An important question to answer is: do T cells in cancer patients have tumor-derived gangliosides incorporated in their plasma membrane? Since the identity of several gangliosides made in abundance in selected cancers has long been identified (Ritter and Livingston, 1991), it should be straightforward to answer this question in systemic T cells of cancer patients. If systemic T cells in patients are susceptible to AICD because of hypersecretion of tumor ganglio-sides then those molecules should be present in patient cells. Furthermore, the concentration of putative tumor-shed gangliosides should be maximal in TIL or other host-derived non-TIL cells present in tumors (fibroblasts or MDSC), also a testable prediction.

5 T-Cell Signaling Affected by Soluble Reactive Oxygen or Nitrogen Metabolites

Several laboratories have pursued experiments suggesting that soluble mediators of T-cell dysfunction are produced by either the tumor cell or host MDSC that accumulate to high abundance in many tumors. These topics will be covered by appropriate experts in other chapters in this monograph. We will comment on those candidate mechanisms only to suggest that a similar level of concern be applied to data implicating those candidate mediators. Either reactive oxygen or nitrogen metabolites (peroxynitrites, hydrogen peroxide or nitric oxide) have been suggested to be involved in induction of various immune cell defects, for example, lytic dysfunction in T cells (Bronte et al., 2005) or NK cells (Kono et al., 1996). Specific biochemical components of the TCR signaling pathway that are targeted by these reactive molecules have not been identified, with the exception of TCRζ postulated to be selectively degraded after T-cell exposure to H2O2 and other soluble factors (Kiessling et al., 1999).

6 Inhibition of TIL Signal Transduction by Tumor

In contrast to the somewhat contradictory data concerning the physiology and function of systemic T cells in tumor-bearing hosts, there is almost universal acceptance of the notion that TIL are severely inhibited in lytic function. This makes conceptual sense since if the tumor, or host response to the tumor, produces immune cell signaling inhibitory factors, then those factors should be in the highest concentration closest to the tumor. Since TCR signaling is required for cytolysis, the presence in tumor tissue of T cells whose antigen-specific functions can be demonstrated in vitro upon purification but whose lytic function in situ is not readily detected (Bronte et al., 2005) implies tumor-induced inhibition of TCR signaling in situ. Freshly isolated CD8+ TIL are, like TIL in situ, lytic-defective and when analyzed in in vitro signaling assays using cognate tumor cells as stimulus have been shown to have a blockade in the most proximal portion of the TCR signaling pathway (Koneru et al., 2005; Radoja et al., 2001). TIL receive initial antigen signals upon contact with cognate tumor cells but are unable to perpetuate the signal downstream past p56lck activation. (A detailed description of the regulation of proximal TCR signaling in T cells is provided in the following section.) Thus, PKC translocation/activation, ERK activation and calcium flux are blocked in spite of having been triggered by contact with antigen-expressing target cells.

We have addressed one unanswered question concerning TIL lytic dysfunction: are the signaling and lytic defects which characterize TIL induced in any memory/effector T cell which enters the tumor environment or does the in vivo induction of lytic defects require antigen-specific interaction between the T cell and the tumor cell? We took advantage of the observation of others that after infection with Listeria monocytogenes (genetically modified to express ovalbumin) has been cleared in mice, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells populate the non-lymphoid peripheral tissues (Masopust et al., 2001; Pope et al., 2001). As opposed to TIL which are lytic defective until briefly cultured in vitro, these cells are lytic towards the model antigen expressed by the recombinant L. monocytogenes immediately upon isolation (Masopust et al., 2001). (Like antitumor TIL, CD8+ anti-ova T cells are memory/effector cells as determined by several criteria, with the obvious difference being lytic capability.) We reasoned if anti-ova T cells isolated from non-lymphoid tissues of tumor-bearing mice are lytic but if isolated from tumor tissue are non-lytic then that would indicate that the tumor microenvironment induces the lytic defect. Furthermore, induction of lytic defects would not require antigen-specific interactions in the tumor.

C57BL/6 mice were infected with a sublethal dose of L. monocytogenes engineered to express chicken ovalbumin (“L. monocytogenesova”). When infection cleared 10 days post-infection, mice were injected with MCA38 tumor cells and 20 days later total CD8+ T cells were isolated from tumors. In mice recovering from L. monocytogenes infection a reasonable percentage of non-lymphoid CD8+ T cells are anti-ova CTL (Masopust et al., 2001); therefore, we anticipated that TIL would contain both anti-MCA38-reactive T cells and anti-ova-reactive T cells. Immediately upon isolation TIL were tested for lytic function using as target cells either EL-4 cells, EL-4 cells pulsed with the synthetic peptide comprising the ovalbumin epitope presented by Kb (SIINFEKL) or cognate MCA38 tumor cells. There was robust SIINFEKL-specific killing of pulsed EL-4 cells but not of either non-pulsed EL-4 targets or cognate tumor cells. We interpret this result to mean that simple presence in the tumor microenvironment does not induce lytic dysfunction; infiltrating T cells must be (somehow) rendered susceptible to the tumor-derived inhibition of signaling. Since anti-MCA38 TIL are inhibited by cognate tumor cells in cytolysis this finding suggests that antigen-specific recognition is needed to induce proximal signaling defects. This observation also argues against the production of a soluble factor by the tumor that inhibits T-cell signaling.

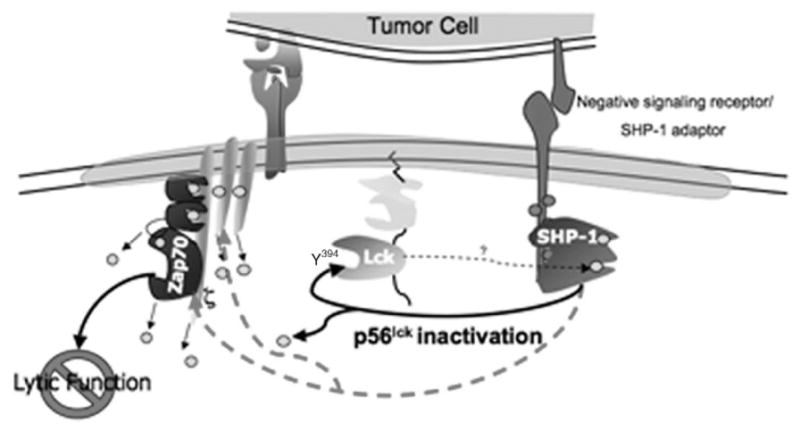

The TIL proximal signaling block was mapped by a combination of biochemical and functional assays to reveal that, upon initial contact with cognate tumor target cells, p56lck was activated but becomes rapidly inactivated and therefore unable to phosphorylate one of its targets, kinase ZAP70. p56lck inactivation, by dephos-phorylation of the activation motif containing Y394, was shown to be mediated by Shp-1 (Monu, in press, 2007). Those data show that (1) TCRζ, previously suggested to be absent in TIL—in the same tumor model (Mizoguchi et al., 1992)—is in fact not absent and becomes phosphorylated upon tumor contact, (2) MDSC, which in other models have shown a dramatic phenotype in terms of inhibition of antitumor T-cell functions (Gabrilovich, 2004), do not mediate the lytic defect in TIL (Frey and Monu, 2006) and (3) antigen-specific interaction between the TIL and tumor is required to induce lytic dysfunction.

Since cognate MCA38 tumor cells cause induction of proximal TCR signaling defects in TIL (Frey and Monu, 2006; Koneru et al., 2005; Radoja et al., 2001) but it is not certain that the mechanism for signaling inhibition which we describe will be utilized for all tumor types, in the following sections we present (to the best of our ability) a synopsis of proximal TCR signaling in T cells in the hope that other models of dysfunctional antitumor T-cell function may be understood in this context. It should be apparent that the complexity of regulation of proximal TCR-mediated signaling provides robust opportunities for interference by tumor-induced factors.

7 Signal Transduction in Cytolytic T Cells

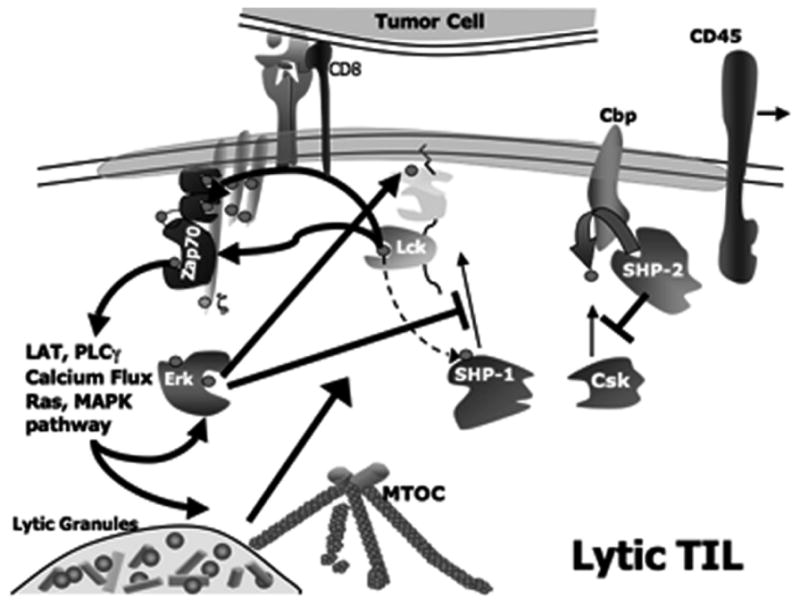

Lytic function of effector CD8+ T cells is dependent upon oligomerization of molecules involved in signal transduction and is initiated by interaction of the antigen receptor (TCRαβ) with cognate peptide ligand:MHC Class I proteins (Kagi et al., 1996) (Fig. 1). Proteins of the TCR complex are synthesized individually and have been shown to assemble in the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi and, upon binding of the TCRζ chain, the complex moves en bloc to the plasma membrane (Alarcon et al., 2003). Other proteins that associate with the TCR complex on activation are recruited upon TCR binding cognate ligand, such as ZAP70 and LAT (Fig. 1). Non-antigen receptor components of the signaling complex either are located in the cytosolic face of endomembranes (Kabouridis et al., 1997), as soluble proteins in the cytoplasm (Cherukuri et al., 2001; Clements et al., 1999; Rudd, 1999), or are integral plasma membrane proteins (Schraven et al., 1999), but after recruitment to the TCR complex enter into close functional association with one another (Cherukuri et al., 2001; Kane et al., 2000). Antigen recognition induces either a conformational change in, or low-order aggregation of, the TCR (Fernandez-Miguel et al., 1999). The coreceptor CD8, an integral membrane protein heterodimer of α and β chains, is next recruited to the TCR complex wherein it functions to enhance the sensitivity of antigen recognition by stabilizing the low-affinity TCR-MHC/peptide interaction (Zamoyska, 1998). Prior to antigen recognition-induced recruitment of CD8 to the TCR, CD8 is associated with the src-family kinase p56lck. Thus, recruitment of CD8/p56lck to the antigen receptor serves several functions: it permits the establishment of a stable higher order oligomeric signaling complex thought to be necessary for accumulation of sufficient information to signify an authentic activation signal, and it causes the association of the kinase most proximal in the signaling cascade with its substrates. Phosphorylation of the TCRζ chain by p56lck upon ligand binding is a very early biochemical consequence of antigen recognition and initiates T-cell “triggering”, which results from tyrosine phosphorylation of certain consensus amino acid motifs (ITAMs). After recruitment of p56lck, phosphorylation of several associated molecules within the TCR complex rapidly occurs and also the recruitment of additional proteins that are requisite components in perpetuating signal transduction, which are in turn activated by phosphorylation (Samelson, 2002).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of proximal TCR signaling in lytic TIL

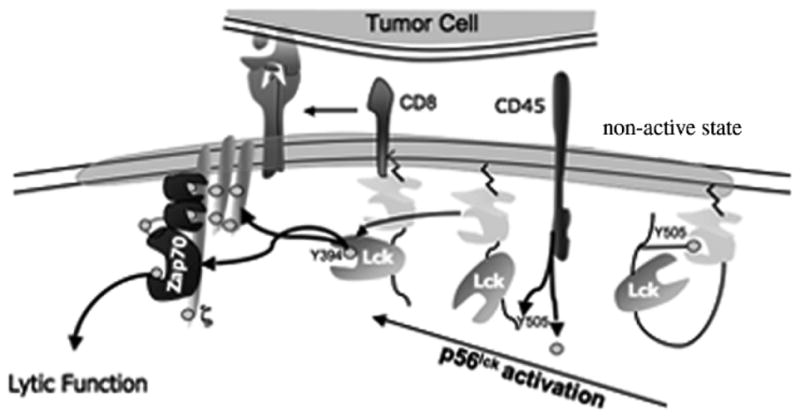

In addition to causing recruitment into proximity to its immediate downstream target (TCRζ), antigen recognition causes activation of the kinase function of p56lck. In T cells whose TCR is not engaged with cognate antigen (aka, “resting” cells), p56lck exists poised for activation without a requirement for synthesis of any additional factors, a design that permits rapid cell activation (Fig. 2). Activation of p56lck is thought to be by autophosphorylation of a specific tyrosine (residue 394 in mouse, although there may be serine/threonine phosphorylation associated with activation), an event that is prevented by restraint of intermolecular folding, in turn caused by phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue (position 505 in mouse) located near the carboxyl terminus. Regulation of Y505 phosphorylation is discussed in detail in the next section and regulation of phosphorylation of the activation motif containing Y394 is discussed here.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of activation of p56lck

In T cells at rest, the p56lck inhibitory motif (containing Y505) is phosphory-lated (by a negative regulatory kinase Csk), which as mentioned above prevents autophosphorylation. Upon antigen recognition, through its association with CD8, p56lck is brought into proximity with the TCR complex. Coincident with recruitment of p56lck, the positive regulatory phosphatase CD45 dephosphorylates p56lck Y505 permitting p56lck autophosphorylation. (Activating signals which enable CD45 to act on p56lck Y505 are unknown but may be provided in trans by counterligands on antigen-bearing target cells.) A second substrate for CD45 is the integral membrane adapter protein that recruits Csk to the plasma membrane, Cbp. (Regulation of the p56lck Y505 phosphorylation cycle is discussed in detail below.) Thus, at the initiation of T-cell activation, CD45 relieves tonic inhibition of p56lck permitting autophosphorylation coincident with coreceptor-mediated recruitment of p56lck into proximity with its substrate TCRζ and other substrate components of the TCR complex, e.g., CD3. The next biochemical event is recruitment of ZAP70 to phosphorylated TCRζ and CD3ε chains (Samelson, 2002; Weiss and Littman, 1994) whereupon ZAP70 is phosphorylated by p56lck. The nascent lipid raft now contains the TCR complex and a raft-associated adapter protein LAT which is available for phosphorylation by ZAP70. Then additional kinases and adapter proteins (e.g., SLP-76, Gads, Grb2, Vav, Nck, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and PLCγ-1) are recruited to phosphorylated ZAP70 in a specific spatio-temporal manner ultimately resulting in calcium flux. TCR-mediated activation of effector-phase functions in CD8+ cells requires calcium flux in that all downstream effector-phase functions are abrogated by events that impede calcium flux.

Following this early phase of signaling (which is quite rapid, ca. within seconds after antigen recognition), subsequent effector functions (such as reorganization of the cytoskeleton, affinity maturation of LFA-1 and subsequent tight adhesion to target cell (Koneru et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2001), cytokine secretion, mobilization of the MTOC to the immunological synapse (IS) and vectoral discharge of lytic granules) result from coordinated activation of additional downstream signaling pathways (involving other kinases: PI 3-kinase, protein kinase C and MAP kinase (Radoja et al., 2006)), occurring after 1–5 min of contact with antigen-expressing target cells. Thus, the lytic phenotype of an effector CD8+ T cell does not follow a strict linear progression of activation/signal transduction, instead results from a complex interrelated program involving several signaling cascades. Importantly, tonic inhibition of p56lck, the kinase most proximal in the signaling cascade which mediates the initiation of TCR-mediated signaling, is pivotally poised to permit fine control of immune response modulation (Torgersen et al., 2002).

8 Regulation of p56lck Activity by Inhibitory Phosphatases

In addition to control of phosphorylation of p56lck Y394 by relief of tonic autoin-hibition, phosphorylation of Y394 is negatively regulated by the action of inhibitory phosphatases, primarily Shp-1 and PEP (Mustelin et al., 2005). p56lck is a substrate for Shp-1 (Chiang and Sefton, 2001), and other components of the proximal signaling complex are possible substrates (ZAP70, LAT, Vav, Grb2, SLP-76 and PLCγ-1 (Kautz et al., 2001; Plas et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2003)). Shp-1 is a non-membrane protein tyrosine phosphatase that contains two amino terminal-located SH2 domains, a single phosphatase domain and a carboxyl terminus containing two sites for tyrosine phosphorylation (Siminovitch and Neel, 1998). The role of Shp-1 in negative regulation of immune cell signaling has been widely studied using the mutant mouse, motheaten (me/me). These mice express defective Shp-1 and exhibit a panoply of hematopoietic defects suggesting that Shp-1 plays an essential role in regulating signal transduction in hematopoietic cells (Shultz et al., 1993). Defects include hyperproliferation of macrophages and neutrophils but also abnormal B- and T-cell hyperresponsiveness and development (Hayashi et al., 1988; Lorenz et al., 1996). Shp-1-mediated downregulation of activation of lytic T cells involves both single and double negative and positive feedback circuits which serve to ensure that commitment of a cell to lytic function is restrained unless positive feedback signals are sufficiently robust to overcome the endogenous restraint (Mustelin et al., 2005).

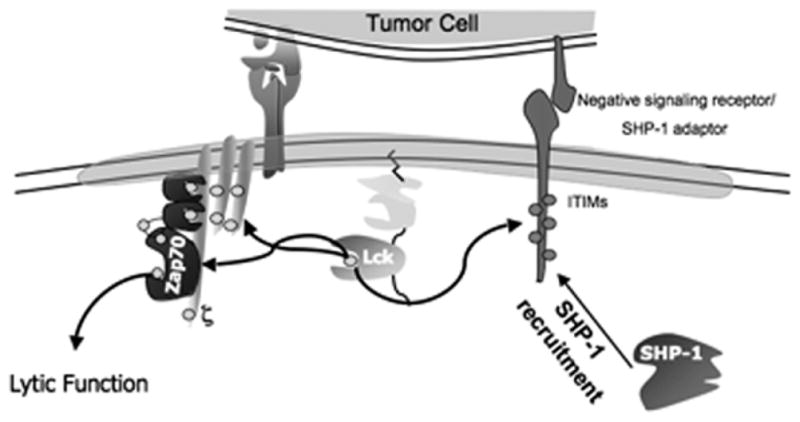

Prior to activation, one of the Shp-1 SH2 domains interacts with and shields the catalytic domain from binding to substrate (Pei et al., 1994). (It is not known whether there is phosphorylation of specific residues associated with maintenance of the sterically inhibited state as there is for p56lck—see below). Upon activation, reflected in phosphorylation at several amino acids, especially Y564, which is accomplished by p56lck (itself a target of Shp-1 therein illustrating a complex regulation program involving multiple negative feedback loops), intermolecular interactions are relaxed and its SH2 domain can now bind to the SH2 domain of binding partners and substrates. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Shp-1 is required for enzymatic activity, but occurs coincident with—or immediately following—localization at the plasma membrane in proximity with its substrates. Shp-1 movement from the cytosol to the membrane is by recruitment to an integral membrane protein, one of a family of “inhibitory signaling receptors” (or adapter proteins) which contain in their cytoplasmic tails a motif for binding Shp-1, the ITIM (D’Ambrosio et al., 1995; Neel, 1997) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Recruitment of Shp-1 to the plasma membrane into proximity with p56lck is mediated by activation (tyrosine phosphorylation) of an inhibitory signaling receptor containing ITIM motifs

Activation of Shp-1 enzymatic activity is dramatically enhanced upon binding to inhibitory receptors, ~10–100 fold (Chiang and Sefton, 2001), implying that recruitment to inhibitory receptors may be the major activation mechanism for Shp-1. Many inhibitory signaling receptors are expressed in different hematopoietic cells and have been shown to be able to recruit Shp-1 to the membrane including NK immunoglobulin-like receptors (Vivier and Anfossi, 2004), siglecs (Varki and Angata, 2006) and leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptors (Ly49 molecules) (Vivier and Daeron, 1997). An example of the dependence of Shp-1 activity upon recruitment to the inhibitory signaling receptor is shown by the phenotype of mice deficient for CD22, an inhibitory signaling receptor involved in regulation of signaling in B cells (O’Keefe et al., 1996). These mice have B-cell hyperproliferation (with attendant increased calcium flux) and decreased Shp-1 recruitment after ligation of the antigen receptor, although Shp-1 can be activated. ITIMs resemble in mechanism of action and function the ITAM motif expressed in adapter proteins in the immunoreceptor signaling pathway (e.g., TCRζ) in that the ITIM becomes tyrosine phosphorylated upon antigen recognition by the immune cell, thought by the kinase that is ultimately targeted for inhibition (Fig. 4). In addition, the extracel-lular portion of the inhibitory receptor interacts with a counterligand expressed on target cells. The molecular function of this interaction is not known but may serve to stabilize the inhibitory receptor in proximity with the antigen receptor as well as to influence the conformation of the cytoplasmic domain permitting phosphorylation of the ITIM.

Fig. 4.

ITIM motifs are phosphorylated by tyrosine kinases requiring interaction of the inhibitory signaling receptor with its cognate ligand

Control of Shp-1 activity is complex having multiple different but interacting positive and negative feedback regulatory circuits. Perhaps regulation of Shp-1 can be categorized into two general programs: direct and indirect regulation, each of which has two (approximate) kinetic classes of potential mechanisms, rapid and late-acting. For example, phosphatases can be directly regulated by reactive oxygen species (H2O2) which has been shown to be produced in neutrophils, and potentially other hematopoietic cells (Brumell et al., 1996; Meng et al., 2002). Hydrogen peroxide rapidly oxidizes an active site cysteine residue resulting in inhibition of activity (and thus the inability to inactivate target kinases). (In this regard, as discussed in an earlier section, the H2O2 reported to be copiously produced by MDSC that accumulate in tumor and peripheral lymph tissues (Kono et al., 1996) possibly is in fact not expressed in situ since proximal signaling in antitumor T cells (especially TIL) is defective. If Shp-1 were rendered inactive by elevated local H2O2 levels, enhanced, not suppressed, kinase activity would be expected.) Another mechanism for Shp-1 inactivation involves displacement from proximity to candidate targets. This involves multiple additional protein:protein interactions and is likely slower to instigate since it requires detachment from its binding partner (the inhibitory signaling receptor) that in turn requires either an active dephosphorylation of the receptor ITIM or a diminution of a kinase activity required to maintain ITIM phosphoryla-tion. Alternatively, interaction of the inhibitory signaling receptor with its counterli-gand may be disrupted which may permit either the inhibitory signaling receptor to move out of proximity to the Shp-1 target kinase or to cause a change in conformation of the domain containing the ITIM therein blocking its phosphorylation.

Indirect regulation would include mechanisms that do not directly affect Shp-1 activity or proximity to substrate. For example, modification of target p56lck to obviate accessibility to Shp-1 could prevent kinase inactivation in spite of activation and recruitment of Shp-1. Although such a function for known p56lck-binding proteins (e.g., LIME (Brdickova et al., 2003; Hur et al., 2003), CAML (Tran et al., 2005)) has not been described, shielding from Shp-1 access by a non-p56lck protein is conceivable. However, an induced conformational change in a Shp-1 binding domain (SH2) in p56lck has been reported which results from phosphorylation of p56lck Ser59 by ERK (Stefanova et al., 2003). Phosphorylation of p56lck on serine/threonine residues has been long known and associated with enhanced kinase activity (Joung et al., 1995; Watts et al., 1993). Phosphorylation on p56lck Ser59 is now hypothesized to reflect robust TCR-mediated signaling with attendant ERK activity. According to this notion, when the quality or duration of antigen stimulation is insufficient or diminished, ERK activity (or its localization proximal to p56lck) decreases and thus cannot phosphorylate p56lck Ser59 permitting a conformation that is accessible to Shp-1 (Stefanova et al., 2003). Another example of indirect regulation of Shp-1 activity is that the inhibitory receptor itself can be a substrate for Shp-1 (Blasioli et al., 1999) which, when the ITIM is dephosphorylated, no longer binds Shp-1. Perhaps this occurs after the preferred substrate (p56lck) has been sufficiently dephosphorylated and would be therefore operative at later times following inhibition of signaling.

9 cAMP-Dependent Modulation of Proximal TCR Signal Transduction by Control of Csk Activity

As mentioned above, control of signaling in T cells can be regulated by the activity of various proteins which function at several different levels in the TCR signaling cascade: positive regulatory kinases (p56lck, ZAP70, ERK, phospholipase C, protein kinase C), adaptor molecules (Csk binding protein, Cbp, and linker for activation of T cells, LAT), positive regulatory phosphatases (CD45 and Shp-2), negative regulatory kinases (Csk and PKA), negative regulatory phosphatases (Shp-1 and PEP) and other proteins which function to regulate the activity of signaling components. This latter category includes enzymes involved in posttranslational modification of kinases and phosphatases, e.g., acylation (Mor and Philips, 2006; Resh, 1994), and/or proteins responsible for the subcellular localization of kinases and phosphatases, e.g., Lad (Choi et al., 1999), LIME (Brdickova et al.,2003; Hur et al., 2003), Cbp (Brdicka et al., 2000) and β-arrestin (Tedoldi et al., 2006), and proteins involved in downregulation of signaling enzymes, e.g., ubiquitin ligases (Hawash et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2005).

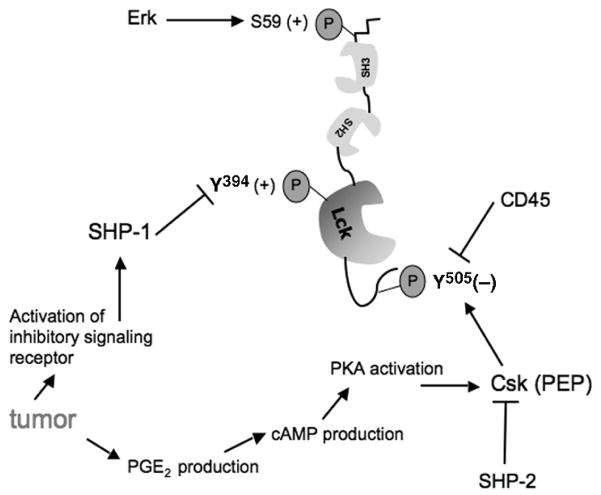

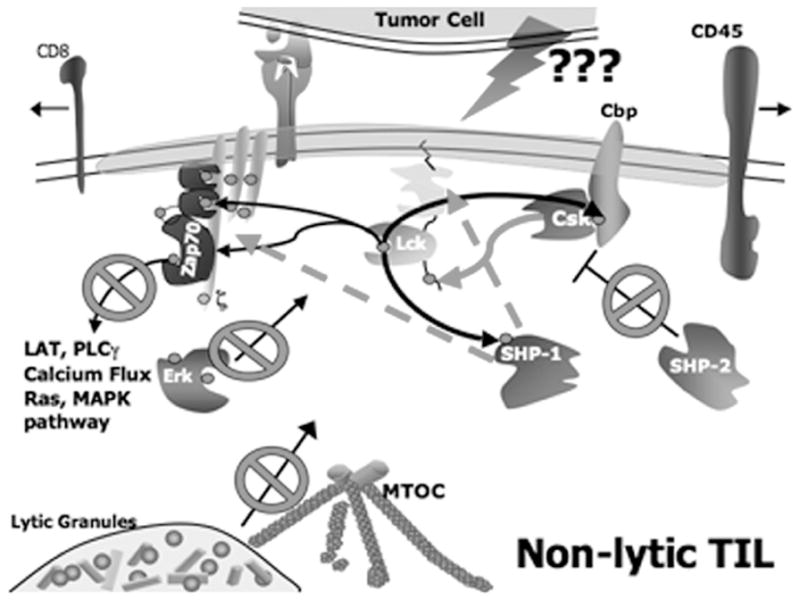

The most proximal kinase responsible for control of T-cell activation is p56lck whose major structural features were described above. Two characteristics of p56lck suggest it is an ideal candidate for negative regulation by extrinsic factors: it is positioned at the apex of the TCR cascade, thus if inhibited will effectively disable all T-cell function, and its inherent complex regulation—which is designed to permit rapid change in kinase activity—provides multiple potential targets for negative regulation. p56lck activity is influenced by phosphorylation of Tyr394 (in the murine enzyme, contained within the activation motif) whose regulation by inhibitory phosphatases was discussed above. In addition to the phosphorylation status of the activation motif, p56lck function is also regulated by phosphoryla-tion of the inhibitory motif containing Tyr505. Regulation of the p56lck inhibitory motif is complex, being affected by the activity of several enzymes, and is directly mediated by the opposing activities of the inhibitory kinase Csk and the positive regulatory phosphatase CD45. p56lck Tyr505 is a major target for phosphorylation by Csk, which when phosphorylated causes p56lck to fold such that autocatalytic phosphorylation of Tyr394 (and enzyme activation) is prevented (Nada et al., 1991). Therefore, since TIL are blocked in proximal signal transduction (Frey and Monu, 2006; Koneru et al., 2005; Radoja et al., 2001), tumor-induced enhanced Csk activity may be a candidate mechanism for inhibition of antitumor T-cell activation and therein lytic function. As such, analysis of the activation status of p56lck in TIL (to determine if the target of Csk—p56lck Tyr505—is phosphorylated) will implicate Csk in the defective lytic phenotype of antitumor T cells. To date, however, only one publication has examined the phosphorylation status of Csk in TIL (Koneru et al., 2005). Thus, understanding the mechanism by which Csk activity is regulated may reveal if and how the tumor microenvironment might regulate p56lck activity and therein effector T-cell function (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic of tonic balance of p56lck activation

Activation of primary T cells by only TCR crosslinking (“signal 1”) results in recruitment of G-proteins into lipid rafts which precedes elevation of cAMP levels (Oh and Schnitzer, 2001). Although cAMP has multiple effects on cell metabolism, it has been long known to inhibit T-cell activation (Kammer, 1988), most likely due to activation of PKA (Tasken and Aandahl, 2004) that in turn activates Csk (by phosphorylation of Ser364 (Vang et al., 2001)) which then dampens p56lck activity (Bergman et al., 1992). (In addition, PKA can also directly phosphorylate p56lck at Ser42 which may affect the binding specificity of the adjacent SH2 domain (Winkler et al., 1993). Also, PKA activation-dependent negative regulation of signaling in NK cells and B cells has also been reported suggesting a common mechanism of inhibition of src-family kinase function (Levy et al., 1996; Torgersen et al., 1997).) Coincident with, or closely linked to, activation by PKA, Csk is recruited from the cytoplasm to the lipid raft by phosphorylation of the raft-associated Csk binding protein (Cbp) on Tyr314. Phosphorylation of Cbp is regulated by a kinase, probably p56lck (Brdicka et al., 2000), the target of Csk-mediated inactivation of proximal TCR signaling. Since Csk is localized to the membrane in resting T cells, reflecting Cbp phosphorylation (Davidson et al., 2003), in order for the T cell to productively signal upon antigen recognition, Csk must be either inactivated or displaced from proximity to its substrate (p56lck). This latter mechanism is known to occur upon activation of primary cells and is achieved by dephosphorylation of Cbp by CD45, an event that is one of the very earliest biochemical manifestations of T-cell triggering (Torgersen et al., 2001). CD45 is also able to directly dephosphorylate p56lck Tyr505 (Birkeland et al., 1989; Ostergaard et al., 1989), therein facilitating immediate activation of p56lck function as well as restricting Csk-mediated inactivation.

Conversely, activation of T cells by crosslinking both the TCR and the costimu-latory receptor CD28 results in a reduction of cAMP levels and concomitant diminished activation of PKA, therein avoiding inactivation of p56lck since Csk is not robustly activated (or is sequestered away from its substrate, see below) (Abrahamsen, 2004). Inhibition of cAMP is mediated by phosphodiesterases (PDE), which in T cells is largely accounted for by the PDE type 4 family (“PDE4”, containing four genes and multiple isoforms) (Oh and Schnitzer, 2001). Upon TCR and C28 co-activation PDE4 is recruited to lipid rafts simultaneously with G-proteins, implying that the localization of PDE4 in proximity with its substrate (cAMP) under conditions of coordinate TCR and CD28 stimulation permits obviation of cAMP-mediated inhibition of proximal signaling. Under suboptimal conditions of TCR triggering (e.g., without T-cell costimulation) PDE4 is hypothesized to fail to localize to the lipid raft and is therefore unable to inactivate cAMP (Tasken and Stokka, 2006). In addition, in the case of TIL activation in situ, the activity of PDE4 may be overwhelmed by vigorous production of cAMP which may occur upon Ag stimulation in the presence of significant levels of PGE as may potentially accumulate in the microenvironment. Elevated PGE can result from the activity of cyclooxygenase 2 made either in certain types of tumors or in host inflammatory cells recruited to the tumor site (Riedl et al., 2004; Rodriguez et al., 2005) and has been shown to cause elevation of cAMP in lymphocytes (Goodwin et al., 1981). Thus, PKA will be activated which in turn activates Csk-mediated inactivation of p56lck.

As discussed above, in addition to positive regulation of T-cell signaling by activation of a kinase enzymatic activity (often via phosphorylation, e.g., p56lck Tyr394, ZAP70 Tyr493, PLCγ-1 Tyr783), T-cell signaling can also be negatively regulated by phosphorylation events, e.g., phosphatase Shp-1 or kinases Csk and PKA. Similarly, both positive and negative regulation of signaling can be influenced by the subcel-lular location or compartmentalization, of regulatory enzymes, usually mediated by phosphorylation-dependent alteration of the binding affinity of lipid raft-associated adaptor proteins. As mentioned above, activation of the PKA–Csk negative regulatory path is dependent upon recruitment of Csk to the TCR signaling complex (which is localized in lipid rafts after the TCR is triggered) by phosphorylation of Cbp; in turn PKA is recruited to the raft by phosphorylation of its adapter AKAP (Michel and Scott, 2002). Thus, control of this arm of the inhibitory cascade is mediated by a combination of cAMP-induced activation of PKA activity and unknown events that result in phosphorylation of the adapter responsible for PKA recruitment into proximity to its substrate (AKAP).

Counterbalancing p56lck-dependent recruitment of Csk to Cbp is the activation of two positive regulatory phosphatases which also target Cbp: CD45 and Shp-2. Dephosphorylation of Cbp by CD45 or Shp-2 results in positive regulation of TCR signaling since Csk cannot colocalize with its substrate. As mentioned above, CD45 dephosphorylation of p56lck and Cbp are probably the earliest biochemical events in TCR signaling, a function that is required for release from tonic inhibition of p56lck activation. After initial activation of T cells, coincident with formation of the higher order antigen receptor signaling complex in the lipid raft (ca. <30 s post-triggering), CD45 is physically excluded from the nascent raft which accumulates at the surface of the T cell at the point of contact with the APC. Thus, very rapidly after T-cell activation CD45 is unable to interact with its substrates (Cbp and p56lck) and no longer participates in regulation of signaling. At intermediate-to-later stages of activation, p56lck can phosphorylate Cbp (both being localized in the now large-sized lipid raft), thus initiating the cycle of Csk-mediated downregulation of proximal signaling by facilitating recruitment of Csk into proximity with its target. Opposing Cbp phosphorylation at this stage of T-cell activation is the activity of Shp-2 that can dephosphorylate Cbp therein interrupting Csk-mediated inhibition of sustained p56lck activation (Zhang et al., 2004). Factors that regulate activation and recruitment of Shp-2 are not well understood but possibly reflect downstream kinases (ERK?) whose activation in turn is dependent upon sustained proximal signaling. In other models, a cytoplasmic scaffolding adaptor protein, Gab1, has been implicated in Shp-2 recruitment to the membrane (Itoh et al., 2000; Sachs et al., 2000; Takahashi-Tezuka et al., 1998), although in T cells this subject is relatively unexplored. The regulatory pathway involving Shp-2 illustrates the complex nature of regulation of T-cell activation involving both positive and negative regulatory feedback mechanisms.

In addition, as mentioned previously, cAMP levels are increased in T cells upon activation (Ledbetter et al., 1986) which if unopposed leads to PKA activation and inhibition of TCR signaling (Abrahamsen et al., 2004). Elevated cAMP, and thus PKA activity, may be part of the normal homeostatic mechanism to dampen signaling and therefore restrict T-cell activation, especially in the absence of costimula-tion (see below). A counter-regulatory mechanism exists which functions to limit cAMP-induced PKA-mediated inactivation of p56lck and is envisioned to be operative under conditions of robust T-cell activation, i.e., TCR plus CD28 costimulation (Abrahamsen, 2004). As mentioned above, lipid raft-associated PDE4 activity is enhanced upon concomitant ligation of the TCR and CD28. PDE4 is recruited to the lipid raft in a complex with a cytosolic adaptor protein, β-arrestin, using an unknown mechanism for raft association (Perry et al., 2002). (β-arrestin has several interacting partners and is best characterized in regulation of G-protein receptor signaling (Perry and Lefkowitz, 2002).) It is reasonable to presume that signals which influence the binding affinity of the β-arrestin/PDE4 complex to the membrane (potentially phosphorylation events generated from TCR and CD28 signaling) regulate recruitment of PDE4 to the TCR signaling complex and therein blockade of cAMP-mediated dysregulation of TCR signaling. Regulation of β-arrestin binding of PDE4 and subsequent association with lipid rafts is at present unknown but may be speculated to be mediated by distal TCR-mediated signaling (Tasken and Stokka, 2006). Thus there are two levels of control of PKA activity: its recruitment (to AKAP) and its activation (by cAMP in turn counterbalanced by PDE4, itself controlled by recruitment to the signaling complex).

What factors determine the kinetics of activation of the Csk/PKA-mediated inhibitory regulatory pathway relative to productive TCR signaling is probably dictated by the strength (number of ligands per T cell as well as the binding affinity for a given TCR) and quality (being either agonist, partial agonist or antagonist) of antigen-mediated TCR triggering. In this regard, Tasken and colleagues have hypothesized that signals generated by TCR ligation appear to result in a constitutively active “default pathway” of increased cAMP levels leading to inhibition of signaling (Abrahamsen, 2004). Only when TCR ligation is accompanied by CD28 costimulation are cAMP levels reduced therein relieving PKA/Csk activity and permitting sustained T-cell activation. This notion is conceptually appealing since it provides a mechanism that inherently restricts the potentially excessive activity of CD8+ effector CTL since most target cells (especially epithelia-derived tumor cells) do not express CD28 ligands. According to this line of thinking, upon contact with target cells lacking CD28 costimulatory ligands, CTL receive Signal 1 and are activated to kill but the amount of time a given CTL can degranulate is limited since p56lck activity would be curtailed soon after activation. In addition, activation of the Csk/PKA inhibitory pathway involves additional signaling pathways such as PGE2 which influence the activity of PKA after signaling through non-antigen receptors (Tasken and Stokka, 2006). Ultimately the combination of positive signals (derived from TCR plus costimulation) and negative signals (cAMP) influences the functional status of T cells.

10 Summary

The host immune system is one of the most important elements for protection from tumor development and control of tumor growth. Macfarlane Burnet postulated that a mechanism of immunological character is an evolutionary necessity for protection from neoplastic disease, and the importance of immunosurveillance of cancer has been thoroughly proven. However, an intact immune system often fails to eliminate antigenic tumors and it has been extensively shown that antigen-specific CD8+ TIL are present in most human cancers but are typically non-lytic and unable to mediate tumor eradication (Radoja et al., 2000; Whiteside, 1998).

We feel insufficient research has been focused on the lytic dysfunction of TIL. Apart from research performed by the Whiteside, Finke, Ochoa labs and others demonstrating that some TIL show abnormalities in terms of expression of TCRζ or other TCR-associated signaling proteins (Whiteside, 1999), much of tumor immunology research has focused on enhancement of priming of the immune response. Consideration of the observation that human TIL are antigen-specific, but non-lytic, together with our description of defective lytic function of murine TIL (Koneru et al., 2005; Radoja et al., 2001) and lack of systemic suppression of the immune system in tumor-bearing mice (Radoja et al., 2000), supports the notion that tumor-induced inhibition of TIL lytic function is a common characteristic that may contribute to tumor growth in the presence of antitumor immune response.

The emphasis of our lab to uncover the biochemical basis for TIL lytic dysfunction was predicated on the considerations that because lytic function is dependent upon TCR-mediated signaling and TIL are unable to exocytose lytic granules, residence of antitumor T cells in the tumor microenvironment may induce defective signal transduction. Supporting this hypothesis, our recent work has demonstrated that when conjugated with cognate tumor cells in vitro, signal transduction in non-lytic TIL is blocked, such that proximal tyrosine kinases are not activated, and purified TIL are unable to flux calcium (Koneru et al., 2005). This conclusion is supported by the observation that ZAP70 is only modestly activated and p56lck appears to be inactivated, deficiencies that undoubtedly underlie lytic dysfunction (Fig. 6). In sum, the phenotype of non-lytic TIL appears to result from tumor-induced, Shp-1-mediated, rapid down-modulation of proximal TCR-mediated signaling, which prevents effector-phase function in situ. The factors that cause enhancement of Shp-1 activity in TIL are unknown at present.

Fig. 6.

Schematic of proximal TCR signaling in non-lytic TIL emphasizing inhibition of p56lck activity by Shp-1

Acknowledgments

Work in the author’s laboratory is currently supported by NIH grant CA108573. I am indebted to my students for their dedication and inquisitiveness: I hope that their training proved as pleasurable for them as it was for me.

Abbreviations

- AICD

Activation-induced cell death

- AKAP

A-kinase-anchoring protein

- APC

Antigen presenting cell

- CAML

Calcium modulating cyclophilin ligand

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- Cbp

Csk binding protein

- Csk

Carboxy terminal Src kinase

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- DTH

Delayed-type hypersensitivity

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IS

Immunological synapse

- ITAM

Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- ITIM

Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif

- LAT

Linker for activation of T cells

- LFA-1

Leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (CD11a/CD18)

- LIME

LCK-interacting molecule

- LN

Lymph node(s)

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MTOC

Microtubule organizing center

- PAG

Protein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains

- PDE

Phosphodiesterase

- PEP

Proline, glutamic acid, serine, threonine domain-enriched tyrosine phosphatase

- PGE

Prostaglandin E2

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PLCγ-1

Phospholipase C gamma-1

- SH2

Src homology 2 domain

- Shp-1

SH2-containing tyrosine phosphatase-1

- Shp-2

SH2-containing tyrosine phosphatase-2

- Slp-76

SH2-domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kD

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- TGFβ-1

Transforming growth factor beta-1

- TIL

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- TUNEL

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling

- ZAP70

Zeta-chain-associated protein kinase of 70 kD

References

- Abrahamsen H, Baillie G, Ngai J, et al. TCR- and CD28-mediated recruitment of phos-phodiesterase 4 to lipid rafts potentiates TCR signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173:4847–4858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon B, Gil D, Delgado P, Schamel WW. Initiation of TCR signaling: regulation within CD3 dimers. Immunol Rev. 2003;191:38–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JP, Kudoh S, Melsop KA, et al. T-cells infiltrating renal cell carcinoma display a poor proliferative response even though they can produce interleukin 2 and express interleukin 2 receptors. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1380–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennaceur K, Popa I, Portoukalian J, Berthier-Vergnes O, Peguet-Navarro J. Melanoma-derived gangliosides impair migratory and antigen-presenting function of human epidermal Langerhans cells and induce their apoptosis. Int Immunol. 2006;18:879–886. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman M, Mustelin T, Oetken C, et al. The human p50csk tyrosine kinase phosphorylates p56lck at Tyr-505 and down regulates its catalytic activity. EMBO J. 1992;11:2919–2924. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AC, Singh SM. Gangliosides derived from a T cell lymphoma inhibit bone marrow cell proliferation and differentiation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AC, Singh SM. Inhibition of macrophage nitric oxide production by gan-gliosides derived from a spontaneous T cell lymphoma: the involved mechanisms. Nitric Oxide. 2003;8:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s1089-8603(02)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland ML, Johnson P, Trowbridge IS, Pure E. Changes in CD45 iso-form expression accompany antigen-induced murine T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6734–6738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas K, Richmond A, Rayman P, et al. GM2 expression in renal cell carcinoma: potential role in tumor-induced T-cell dysfunction. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6816–6825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackhall FH, Shepherd FA. Small cell lung cancer and targeted therapies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:103–108. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328011bec3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasioli J, Paust S, Thomas ML. Definition of the sites of interaction between the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 and CD22. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2303–2307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon T, Van Pel A. T cell-recognized antigenic peptides derived from the cellular genome are not protein degradation products but can be generated directly by transcription and translation of short subgenic regions. A hypothesis. Immunogenetics. 1989;29:75–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00395854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brdicka T, Pavlistova D, Leo A, et al. Phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains (PAG), a novel ubiquitously expressed transmem-brane adaptor protein, binds the protein tyrosine kinase csk and is involved in regulation of T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1591–1604. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brdickova N, Brdicka T, Angelisova P, et al. LIME: a new membrane Raft-associated adaptor protein involved in CD4 and CD8 coreceptor signaling. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1453–1462. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte V, Cingarlini S, Marigo I, et al. Leukocyte infiltration in cancer creates an unfavorable environment for antitumor immune responses: a novel target for therapeutic intervention. Immunol Invest. 2006;35:327–357. doi: 10.1080/08820130600754994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte V, Kasic T, Gri G, et al. Boosting antitumor responses of T lymphocytes infil-trating human prostate cancers. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1257–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell JH, Burkhardt AL, Bolen JB, Grinstein S. Endogenous reactive oxygen intermediates activate tyrosine kinases in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1455–1461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski RM, Rayman P, Uzzo R, et al. Signal transduction abnormalities in T lymphocytes from patients with advanced renal carcinoma: clinical relevance and effects of cytokine therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2337–2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi G, Heaney JA, Schned AR, Phillips DM, Branda MT, Ernstoff MS. T-cell receptor zeta-chain expression on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3517–3519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherukuri A, Dykstra M, Pierce SK. Floating the raft hypothesis: lipid rafts play a role in immune cell activation. Immunity. 2001;14:657–660. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang GG, Sefton BM. Specific dephosphorylation of the Lck tyrosine protein kinase at Tyr-394 by the SHP-1 protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23173–23178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YB, Kim CK, Yun Y. Lad, an adapter protein interacting with the SH2 domain of p56lck, is required for T cell activation. J Immunol. 1999;163:5242–5249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CD, Patel VP, Moran M, Lewis LA, Miceli MC. Galectin-1 induces partial TCR zeta-chain phosphorylation and antagonizes processive TCR signal transduction. J Immunol. 2000;165:3722–3729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JL, Boerth NJ, Lee JR, Koretzky GA. Integration of T cell receptor-dependent signaling pathways by adapter proteins. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:89–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran AJ, Huang RR, Lee J, Itakura E, Leong SP, Essner R. Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:659–670. doi: 10.1038/nri1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa MR, Ochoa AC, Ghosh P, Mizoguchi H, Harvey L, Longo DL. Sequential development of structural and functional alterations in T cells from tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5292–5296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulie PG, Lehmann F, Lethe B, et al. A mutated intron sequence codes for an antigenic peptide recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7976–7980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca A, Cheng F, Wang H, et al. Extra-lymphatic solid tumor growth is not immunologically ignored and results in early induction of antigen-specific T-cell anergy: dominant role of cross-tolerance to tumor antigens. Cancer Res. 2003;63:9007–9015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio D, Hippen KL, Minskoff SA, et al. Recruitment and activation of PTP1C in negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling by Fc gamma RIIB1. Science. 1995;268:293–297. doi: 10.1126/science.7716523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D, Bakinowski M, Thomas ML, Horejsi V, Veillette A. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of T-cell activation by PAG/Cbp, a lipid raft-associated transmembrane adaptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2017–2028. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.2017-2028.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix AR, Brooks WH, Roszman TL, Morford LA. Immune defects observed in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;100:216–232. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcetti R, Viel A, Doglioni C, et al. High prevalence of activated intraepithelial cytotoxic T lymphocytes and increased neoplastic cell apoptosis in colorectal carcinomas with microsatellite instability. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1805–1813. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65436-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukers DF, Oudejans JJ, Jaspars EH, et al. All infiltrating T-lymphocytes in Hodgkin’s disease express immunohistochemically detectable T-cell receptor zeta-chains in situ. Histopathology. 2000;36:544–550. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]