Over the last ten years, advances in genotyping and high-throughput sequencing technologies have resulted in an explosion of genetic information. Whereas prior attempts at discovering human genetic differences affecting susceptibility to disease relied on genotyping one or a handful of candidate genetic variants, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have now become a common means of searching for susceptibility genes in an unbiased way. These studies have highlighted the relevance of particular pathways in pathogenesis of infectious and autoimmune disease. Thus, GWAS of clinical phenotypes can alert host-pathogen researchers to unexpected links between their pathway of study and human disease. Complementary to this, cellular GWAS using pathogens as probes can reveal how genetic variation affects cellular processes important for disease pathogenesis.

What Can GWAS Do for Cellular Microbiology? Identification of Genes and Pathways Important in Autoimmune and Infectious Disease Pathogenesis

In GWAS, controls and cases with a disease are genotyped at hundreds of thousands to millions of loci and the genotype frequencies are compared to identify alleles that may be protective or result in increased susceptibility [1]. Prior to the advent of GWAS, a handful of examples demonstrated that common genetic variation could have profound effects on infectious disease susceptibility. The sickle cell allele of hemoglobin protecting against malaria [2] and the CCR5 deletion allele protecting against HIV infection [3] are textbook examples. GWAS provide a way to systematically search for such genetic differences.

GWAS of autoimmune diseases have been particularly successful. For inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a GWAS of 75,000 people revealed 163 loci that can account for ∼15% of the total disease variance of Crohn's disease [4]. The genomic regions implicated by these loci include genes showing a striking enrichment for immune-related gene ontology terms, including regulation of cytokine production and activation of lymphocyte signaling [4]. The causal variants, which nearby genes are affected, and how the affected genes alter pathophysiology are unknown for most of these loci. However, a few successful exceptions should spur researchers to mine this list of disease-relevant genetic differences. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 that results in a truncated protein was identified as a Crohn's disease susceptibility allele [5], [6] prior to the GWAS era through linkage followed by candidate gene studies. NOD2 is a member of the NLR family of intracellular sensors that responds to both bacterial (muramyl dipeptide; MDP) and viral (ssRNA) patterns [7], [8]. Mice with the NOD2 mutation had increased intestinal inflammation in the dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) model of colitis, and macrophages from the mice exhibited increased NF-κB signaling and IL-1β secretion in response to MDP [9]. The first reported GWAS hit for IBD was a non-synonymous mutation in an autophagy gene, ATG16L1 [10]. Prior to this finding, autophagy had not been known to play a role in Crohn's disease susceptibility, and this discovery prompted further research in the interplay of autophagy, infection, and immunity. Recent cellular studies have linked these two susceptibility genes. NOD2 recruits ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane to cause autophagy of invasive bacteria [11], while a separate study showed that NOD2 activation by MDP enhances ATG16L1-mediated autophagy to increase antigen presentation in dendritic cells [12]. These studies of IBD demonstrate how careful and extensive follow-up of GWAS hits can be transformative to the understanding of pathophysiology. Researchers can determine whether their gene of interest has been implicated in GWAS by searching the NHGRI GWAS catalog [13] or the GWASdb website, which manually curates more hits and provides an easy-to-navigate browser [14].

Two successful examples from infectious disease GWAS further show how GWAS can inform our understanding of disease and even lead to changes in clinical practice. GWAS of leprosy have revealed eight loci affecting susceptibility [15], [16]. Overlap in leprosy and IBD-associated GWAS variants has clearly demonstrated the shared genetic underpinnings controlling susceptibility to infectious and autoimmune disease. Five of the eight loci associated with leprosy are also associated with Crohn's disease [4]. For example, an SNP upstream of NOD2 protects against IBD but leads to increased risk of leprosy [4]. Thus, there are phenotypic trade-offs in genetic variation that may only be revealed under certain environmental situations.

GWAS of treatment response to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has prompted changes in clinical practice. Genetic variation at the IL28B locus (encoding interferon lambda-3) has been strongly associated with sustained virological response to pegylated interferon alpha plus ribavirin in patients with chronic HCV infection, with carriers of the beneficial genotype having 2- to 3-fold greater odds of eradicating the virus [17]. This effect appears to be particularly strong in patients with the G1 viral genotype [18]. Genotyping individuals for this variant has now become common in managing treatment [19]. While the clinical utility of IL28B genetic testing may begin to wane in the era of direct-acting anti-HCV drugs, the biological information gleaned from these studies will have lasting value, both in terms of recognizing the role of interferon lambdas in HCV infection, and perhaps as a novel route of therapeutic management [19].

Despite these successes, there are certainly limitations to GWAS [20], [21] and fewer examples of GWAS discoveries in infectious disease than for most common, chronic human diseases. Notably, sample sizes of infectious disease GWAS have been relatively modest compared to other GWAS. Lack of sufficient coverage of variation on genotyping platforms for African populations is also likely partially responsible. Selection of controls is also inherently difficult for infectious disease GWAS, especially for nosocomial and opportunistic infections for which information on pathogen exposure in uninfected individuals may be limited and patients have varied and multiple comorbidities that can lead to confounding. Perhaps most importantly, infectious disease GWAS have an additional source of genetic variation not present in GWAS of other human diseases—genetic variation in the pathogen. This is illustrated above with the recognition that the influence of IL28B genotype on HCV clearance is largely dependent on the viral genome. The host-pathogen arms race results in two moving targets and in some cases tremendous genetic heterogeneity. For example, HIV-1 is incredibly diverse, with thousands of genetically different viruses classified in a complex tree of types, subtypes, sub-subtypes, and recombinant forms [22]. Despite these challenges, loci associated with infectious disease typically have larger effect sizes compared to noninfectious disease GWAS and thus should be a priority [20]. Infectious disease GWAS will benefit from increased sample size, better coverage of variants in genotyping, and stratified analysis to minimize confounding due to variation in the pathogen.

What Can Cellular Microbiology Do for GWAS? Cellular GWAS as a New Discovery Tool

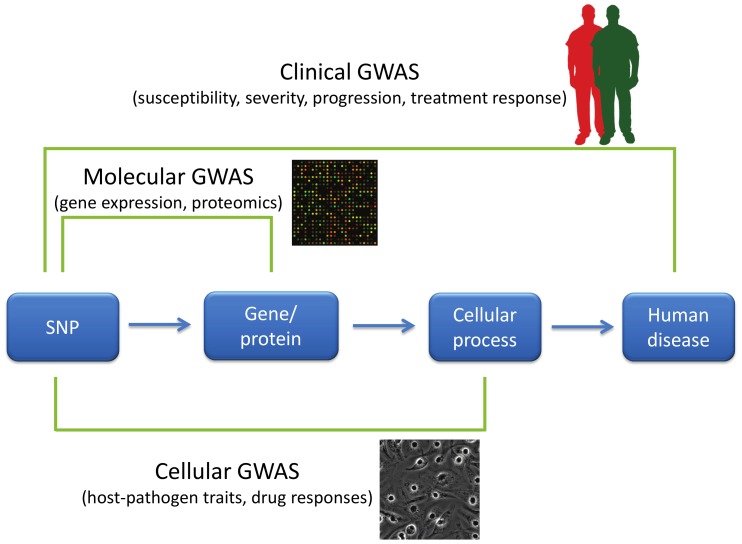

While clinical GWAS have been successful at highlighting important pathways in disease pathogenesis, there is clearly a need for additional approaches directed at understanding how specific genetic variants affect disease. How can we more effectively move from lists of SNPs to greater biological insight? One approach is to complement the GWAS of organismal/clinical traits with GWAS of different phenotypic scales (Figure 1). For several years, molecular GWAS of gene expression have identified genes whose level of transcription is associated with nearby genetic variation (cis-eQTLs; expression quantitative trait loci [23], [24]). These resources are useful for GWAS researchers in trying to narrow down what genes are affected by functional genetic variants within a genomic region. Researchers can take advantage of online tools such as the eQTL Browser [25] to determine if there is human genetic variation near their gene of interest that may regulate levels of expression. The availability of cell lines with alternative alleles, as well as genome engineering approaches to introduce genetic differences into isogenic backgrounds [26], makes this an exercise that can lead to hypothesis-driven experiments to understand how human variants alter cell biology.

Figure 1. GWAS of varying phenotypic scales.

GWAS have primarily been used to characterize disease-related characteristics in patient populations, but new approaches have expanded the phenotypes used in GWAS. “Clinical GWAS” search for associations between genetic differences (primarily in the form of SNPs) and human disease traits such as disease risk, severity of disease, disease progression, and response to treatment. “Molecular GWAS” search for associations between SNPs and molecular phenotypes such as levels of mRNAs, proteins, or metabolites. Finally, “cellular GWAS” connect SNPs to particular cellular processes. Phenotypic variation in these cellular processes can be examined by manipulation either pharmacologically or using pathogens.

The flow of scientific inspiration can also proceed from cellular microbiology to GWAS. Inspired by the way cellular microbiology [27] has led to numerous key discoveries in basic cell biology, cellular GWAS approaches that utilize pathogens as probes can serve to connect cellular processes to human diseases. In a cellular GWAS, cells from hundreds of genotyped individuals are exposed to a stimulus and the varied responses serve as quantitative traits for GWAS. For example, in the platform developed by one of the authors ([28]; Hi-HOST: High throughput Human in vitrO Susceptibility Testing), cellular GWAS was carried out on the phenotype of pyroptosis [29], Salmonella-induced inflammatory cell death. Experimental follow-up of an eQTL near APIP (apaf-1-interacting protein) led to the discovery that APIP is an enzyme in the methionine salvage pathway and that this metabolic pathway regulates caspase-1 activation [30]. Genotyping data for this SNP in patients with the physiological criteria for sepsis suggested that the APIP allele that results in a more robust caspase-1 response in vitro reduced the odds of death [30]. These findings are now being examined further in an APIP mouse model and in patient populations with Salmonella infections. Pyroptosis is just one consequence of Salmonella infection, and by monitoring multiple cellular phenotypes, we are able to probe human variation in macropinocytosis (by measuring Salmonella invasion), endosomal biology (by measuring intracellular survival and replication), and numerous pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways (by measuring the cytokine response).

Not only can cellular GWAS approaches help elucidate clinical GWAS of bacterial infections, but unexpected connections between cellular processes and noninfectious diseases may emerge from this approach. Increasing the number and types of stimuli will lead to a large catalog of cellular GWAS that have targeted various cellular processes. We have thus far focused on Salmonella and Yersinia phenotypes ([28], [30] and D. Ko, unpublished data), while a similar approach has been used for HIV [31]. Cellular GWAS have also been undertaken for several different drug responses [32], [33], and hits from a cellular GWAS of taxol sensitivity showed a statistically significant overlap with a clinical GWAS of peripheral neuropathy induced by this same drug in cancer patients [34]. Cellular GWAS can help to make sense of clinical GWAS associations by revealing what cellular processes may be involved and by providing an experimentally tractable system to allow for hypothesis testing.

Perspective

For the last twenty years, cellular microbiology has provided amazing insights into the physiology of cells [27]. Cellular microbiology is now well poised to contribute to the field of human genetics. Pathogens have clearly been a driving force, and perhaps have even been the main selective pressure, during human evolution [35]. What better way to study functional consequences of common genetic variants that have undergone natural selection than with the agents that have driven that change? Discoveries await both cellular microbiologists and human geneticists, and the results should benefit our understanding of basic biology and susceptibility to disease.

Funding Statement

DCK received funding from the NIAID Northwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (U54 AI057141), an NIAID Research Scholar Development Award (K22 AI093595), and from a Duke School of Medicine Whitehead Scholarship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Raychaudhuri S (2011) Mapping rare and common causal alleles for complex human diseases. Cell 147: 57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allison AC (1954) Protection afforded by sickle-cell trait against subtertian malareal infection. Br Med J 1: 290–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley GA, Smith MW, et al. (1996) Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, ALIVE Study. Science 273: 1856–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, et al. (2012) Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491: 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, et al. (2001) Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 411: 599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, et al. (2001) A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 411: 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, et al. (2003) Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. Implications for Crohn's disease. J Biol Chem 278: 5509–5512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sabbah A, Chang TH, Harnack R, Frohlich V, Tominaga K, et al. (2009) Activation of innate immune antiviral responses by Nod2. Nat Immunol 10: 1073–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maeda S, Hsu LC, Liu H, Bankston LA, Iimura M, et al. (2005) Nod2 mutation in Crohn's disease potentiates NF-kappaB activity and IL-1beta processing. Science 307: 734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstiel P, Till A, Teuber M, et al. (2007) A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet 39: 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Travassos LH, Carneiro LA, Ramjeet M, Hussey S, Kim YG, et al. (2010) Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat Immunol 11: 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooney R, Baker J, Brain O, Danis B, Pichulik T, et al. (2010) NOD2 stimulation induces autophagy in dendritic cells influencing bacterial handling and antigen presentation. Nat Med 16: 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hindorff LA, MacArthur J, Morales J, Junkins HA, Hall PN, et al. A catalog of published genome-wide association studies. Available: http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies/. Accessed 3 July 2013.

- 14. Li MJ, Wang P, Liu X, Lim EL, Wang Z, et al. (2012) GWASdb: a database for human genetic variants identified by genome-wide association studies. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D1047–1054 Available: http://jjwanglab.org:8080/gwasdb/. Accessed 3 July 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang F, Liu H, Chen S, Low H, Sun L, et al. (2011) Identification of two new loci at IL23R and RAB32 that influence susceptibility to leprosy. Nat Genet 43: 1247–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang FR, Huang W, Chen SM, Sun LD, Liu H, et al. (2009) Genomewide association study of leprosy. N Engl J Med 361: 2609–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, et al. (2009) Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 461: 399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi KQ, Liu WY, Lin XF, Fan YC, Chen YP, et al. (2012) Interleukin-28B polymorphisms on the SVR in the treatment of naive chronic hepatitis C with pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin: a meta-analysis. Gene 507: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Urban T, Charlton MR, Goldstein DB (2012) Introduction to the genetics and biology of interleukin-28B. Hepatology 56: 361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hill AV (2012) Evolution, revolution and heresy in the genetics of infectious disease susceptibility. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367: 840–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klein C, Lohmann K, Ziegler A (2012) The promise and limitations of genome-wide association studies. JAMA 308: 1867–1868. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tebit DM, Arts EJ (2011) Tracking a century of global expansion and evolution of HIV to drive understanding and to combat disease. Lancet Infect Dis 11: 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stranger BE, Nica AC, Forrest MS, Dimas A, Bird CP, et al. (2007) Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat Genet 39: 1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeller T, Wild P, Szymczak S, Rotival M, Schillert A, et al. (2010) Genetics and beyond–the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS ONE 5: e10693 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degner JF, Bell JT, Pritchard JK. eQTL Browser. Available: http://eqtl.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/gbrowse/eqtl/. Accessed 3 July 2013.

- 26. Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. (2011) Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res 39: e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cossart P, Boquet P, Normark S, Rappuoli R (1996) Cellular microbiology emerging. Science 271: 315–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ko DC, Shukla KP, Fong C, Wasnick M, Brittnacher MJ, et al. (2009) A genome-wide in vitro bacterial-infection screen reveals human variation in the host response associated with inflammatory disease. Am J Hum Genet 85: 214–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT (2009) Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol 7: 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ko DC, Gamazon ER, Shukla KP, Pfuetzner RA, Whittington D, et al. (2012) Functional genetic screen of human diversity reveals that a methionine salvage enzyme regulates inflammatory cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E2343–E2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Loeuillet C, Deutsch S, Ciuffi A, Robyr D, Taffé P, et al. (2008) In vitro whole-genome analysis identifies a susceptibility locus for HIV-1. PLoS Biol 6: e32 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang RS, Duan S, Bleibel WK, Kistner EO, Zhang W, et al. (2007) A genome-wide approach to identify genetic variants that contribute to etoposide-induced cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 9758–9763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wen Y, Gorsic LK, Wheeler HE, Ziliak DM, Huang RS, et al. (2011) Chemotherapeutic-induced apoptosis: a phenotype for pharmacogenomics studies. Pharmacogenet Genomics 21: 476–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wheeler HE, Gamazon ER, Wing C, Njiaju UO, Njoku C, et al. (2013) Integration of cell line and clinical trial genome-wide analyses supports a polygenic architecture of Paclitaxel-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy. Clin Cancer Res 19: 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fumagalli M, Sironi M, Pozzoli U, Ferrer-Admetlla A, Pattini L, et al. (2011) Signatures of environmental genetic adaptation pinpoint pathogens as the main selective pressure through human evolution. PLoS Genet 7: e1002355 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]