Abstract

Most theories of psychotic-like experiences posit the involvement of social-cognitive mechanisms. The current research examined the relations between psychotic-like experiences and two social-cognitive mechanisms, high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity. In particular, we examined whether aberrant salience, or the incorrect assignment of importance to neutral stimuli, and low self-concept clarity interacted to predict psychotic-like experiences. The current research included three large samples (n = 667, 724, 744) of participants and over-sampled for increased schizotypal personality traits. In all three studies, an interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity was found such that participants with high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity had the highest levels of psychotic-like experiences. In addition, aberrant salience and self-concept clarity interacted to predict a supplemental measure of delusions in Study 2. In Study 3, in contrast to low self-concept clarity, neuroticism did not interact with aberrant salience to predict psychotic-like experiences, suggesting that the relation between low self-concept clarity and psychosis may not be due to neuroticism. Additionally, aberrant salience and self-concept clarity did not interact to predict to other schizotypal personality disorder criteria, social anhedonia or trait paranoia, which suggests the interaction is specific to psychotic-like experiences. Overall, our results are consistent with several social-cognitive models of psychosis suggesting that aberrant salience and self-concept clarity might be important mechanisms in the occurrence of psychotic-like symptoms.

Keywords: Aberrant Salience, Self-Concept Clarity, Psychotic-Like Experiences, Schizotypal Personality Disorder, Schizotypy

Psychotic symptoms include delusions and hallucinations and are a common experience in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and in people at risk for psychosis (e.g., Andreasen, Arndt, Alliger, Miller, & Flaum, 1995). Recent research suggests that psychotic-like experiences may also be relatively common in the general population, with estimates as high as one out of every five people reporting at least one psychotic experience at some point in their lifetime (van Os, Hanssen, Bijl, & Vollebergh, 2001). Psychotic-like experiences are similar to symptoms of psychosis, but in diminished form and may precipitate a psychotic episode (Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman, & Bebbington, 2001). For example, two criteria for schizotypal personality disorder include odd beliefs or magical thinking and unusual perceptual experiences (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), which are similar to the psychotic symptoms of delusions and hallucinations respectively. Many theorists who have attempted to explain the origin of psychosis and psychotic-like experiences have posited a role for social-cognitive mechanisms in the development and maintenance of these experiences (e.g., Beck & Rector, 2005; Bell, Halligan, & Ellis, 2006; Bentall, Corcoran, Howard, Blackwood, & Kinderman, 2001; Fenigstein & Vanable, 1992; Fowler, 2000; Freeman, 2007; Garety, et al., 2001). The current research examined the relations between psychotic-like experiences (i.e. odd beliefs or magical thinking and unusual perceptual experiences) and two social-cognitive mechanisms, aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity.

Aberrant salience is the incorrect assignment of importance to neutral stimuli and has been proposed to be centrally involved in psychosis and psychotic-like experiences (Gray, Feldon, Rawlins, Hemsley, & Smith, 1991; Kapur, 2003; Roiser et al., 2008). Anecdotal reports of people with psychosis suggest that they initially often go through periods in which stimuli that ordinarily would not seem significant become much more salient and important (Bowers, 1968; Moller & Husby, 2000). Based in part on these phenomenological observations, Kapur (2003) suggested that occurrences of aberrant salience may be central to the development of psychosis. Positing a role for aberrant salience in psychosis is also derived in part from research on normal incentive salience processes. Incentive salience refers to the “wanting” and motivational importance component of learning as opposed to the “liking” component (Berridge, 2007). Given the role of dopamine in incentive salience, this suggests that dopamine dysregulation should be associated with aberrant salience (Kapur, 2003). This is consistent with a long line of research supporting an association between psychosis and increased subcortical dopamine (e.g., Seeman, 1987). For example, brain imaging studies have found dysregulated dopamine activity when people with schizophrenia are actively psychotic (e.g., Laruelle & Abi-Dargham, 1999) and in the prodromal phase of the illness (Howes et al., 2009). Therefore, both phenomenological and neurobiological research suggests a role for aberrant salience in psychosis and psychotic-like experiences.

A role for aberrant salience in psychosis and psychotic-like experiences is also consistent with most previous models of psychotic-like experiences. Two social-cognitive mechanisms that are common to nearly all models of psychotic-like experiences are (a) aberrant salience or anomalous experiences and (b) self-relevant information processing (e.g., Bell et al., 2006; Bentall et al., 2001; Freeman, 2007). According to these models, anomalous experiences contribute to psychosis because people adopt delusional beliefs in part to account for these anomalous experiences (Maher, 1974). In addition, a number of these models have also hypothesized that aberrant salience is the mechanism that contributes to the occurrence of anomalous experiences (Freeman, 2007; Kapur, 2003) or the mechanism by which these experiences are attributed to external sources.

Until recently, there was not a direct method for measuring aberrant salience. In a series of studies, the Aberrant Salience Inventory was recently developed (ASI; Cicero, Kerns, & McCarthy, 2010) and found to be a valid and reliable measure of aberrant salience in people at risk for the development of psychosis. The ASI is distinct from, albeit highly correlated with, other measures psychotic-like experiences such as the Perceptual Aberration (Chapman, Chapman, & Raulin, 1978) and Magical Ideation Scales (Eckblad & Chapman, 1983). For example, only the ASI was correlated with behavioral activation, which is also thought to reflect increased subcortical dopamine, and the ASI was less strongly correlated with social anhedonia than were the Perceptual Aberration and Magical Ideation Scales. The current research aims to further test the nomological network of the construct of aberrant salience by using the ASI to examine theories of psychotic-like experiences that posit a central role for aberrant salience.

Another social-cognitive mechanism of psychotic-like experiences examined in the current research is low self-concept clarity. Self-concept clarity (SCC) refers to “to the extent to which one’s beliefs about one’s attributes are clear, confidently held, internally consistent, stable, and cognitively accessible” (Stinson, Wood, & Doxey, 2008, p. 1541). People with low self-concept clarity have been found to report more fluctuating levels of self-esteem (Kernis, Paradise, Whitaker, Wheatman, & Goldman, 2000), which is associated with a host of negative psychological outcomes (Campbell et al., 1996).

As mentioned, researchers have long suggested that basic problems with self-relevant information processing may be related to the development of psychosis (e.g., Hemsley, 1998; Parnas, Handest, Saebye, & Jansson, 2003; Raballo, Saebye, & Parnas, 2009). Recently, some evidence suggests that low self-concept clarity in particular might be related to psychotic-like experiences. One phenomenological study concluded that “disturbance of perception of self” is a core experiential dimension of the development of psychosis (Moller & Husby, 2000), with this disturbance described as a loss of a clear conceptualization of the self. For instance, people in the prodromal phase of psychosis reported often feeling like they were confused about their identities (Moller & Husby, 2000), suggesting low self-concept clarity. Hemsley (1998) referred to this phenomenon as a “gradually developing instability in the sense of personal identity (p.117).” Hence, it is possible that low self-concept clarity might be a specific type of self-processing disturbance related to psychotic-like experiences.

As previously discussed, a role for both aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity in psychotic-like experiences is consistent with nearly all models of psychosis. However, another important feature of social-cognitive models of psychosis is that they suggest that by themselves neither aberrant salience nor self-processing disturbances may be sufficient to produce psychotic-like experiences. Instead, these models posit that the combination of aberrant salience and self-processing disturbances results in psychotic-like experiences (Bell, et al., 2006).

Therefore, based on previous psychotic-like experiences theories and research, aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity might be two social-cognitive mechanisms that interact to predict psychotic-like experiences. Nevertheless, a number of important questions have not been examined in previous research. For instance, no previous research has actually examined whether aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity interact to predict psychotic-like experiences. Similarly, previous research has not examined whether aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity interact to uniquely predict psychotic-like experiences and do not interact to predict other aspects of schizotypal personality disorder. Furthermore, although previous research suggests that low self-concept clarity might be associated with psychotic-like experiences, no previous research has directly measured and examined whether self-concept clarity is associated with psychotic-like experiences. Given that self-processing disturbances are also associated with increased neuroticism (Campbell, et al., 1996), it is important to examine whether self-concept clarity is uniquely associated with psychotic-like experiences or whether neuroticism would be similarly associated with psychotic-like experiences.

In three studies, the current research examined whether aberrant salience and self-concept clarity interacted to predict psychotic-like experiences, specifically magical ideation and perceptual aberration (Chapman et al., 1994). In addition, Study 1 tested whether this interaction was specific to psychotic-like experiences and not to another facet of schizotypal personality disorder, social anhedonia, which is closely related to the “lack of close friends” criterion of schizotypal personality disorder. In Study 2, we attempted to replicate the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting psychotic-like experiences, and to test the specificity of the interaction by including a supplementary measure of delusion-like beliefs, the Peters Delusion Inventory (PDI; Peters, Joseph, Day, & Garety, 2004). In Study 3 we tested whether only self-concept clarity interacted with aberrant salience to predict psychotic-like experiences, or whether neuroticism would also interact with aberrant salience to predict psychotic-like experiences. Finally, in Study 3, we tested whether the interaction was specific to psychotic-like experiences or whether aberrant salience and self-concept clarity would interact to predict paranoia.

Study 1

The main goal of Study 1 was to test the prediction that aberrant salience and self-concept clarity interact to predict psychotic-like experiences. Additionally, we tested whether this interaction is specific to predicting psychotic-like experiences and whether aberrant salience and self-concept clarity would not interact to predict social anhedonia.

Method

Participants

Participants were 667 undergraduate students who took part in the study as partial fulfillment of a course requirement. To ensure adequate numbers of participants with high levels of schizotypy, participants were prescreened from a larger pool of participants (n= 1,901), by completing abbreviated versions of the Perceptual Aberration Scale (PerAb; Chapman, et al., 1978), Magical Ideation Scale (MagicId; Eckblad & Chapman, 1983), and Social Anhedonia Scale (SocAnh; Chapman, Chapman, & Raulin, 1976). Participants scoring two standard deviations above the mean or higher on these scales or a combined three standard deviations above the mean on PerAb and MagicId were recruited to the laboratory for an individual testing session. Participants who scored less than 0.5 standard deviations above the mean on all three scales were also recruited. When participants came to the lab, they completed full versions of these three scales. All analyses are based on the full version of the scales. According to previous research (Kerns & Berenbaum, 2000), 41 participants met criteria for high positive schizotypy and 70 participants met criteria for high negative schizotypy. This strategy of oversampling resulted in a wider range of scores in all three studies when compared to unselected samples. Sixty-two participants were excluded for having Chapman Infrequency scores of three or greater. Participants ranged from 18–26 years old, with an average age of 18.47 (SD = 0.93). Participants were 63% female, 86% White, 6% African-American, and 8% other.

Measures

Aberrant Salience

Aberrant Salience was measured with the Aberrant Salience Inventory (ASI; Cicero, et al., 2010). The ASI is a 29-item yes-no questionnaire that has five subscales measuring different aspects of the experience of aberrant salience including feelings of increased significance (e.g., Do certain trivial things suddenly seem especially important or significant to you?), sharpening of senses (e.g., Do your senses ever seem especially strong or clear?), impending understanding (e.g., Do you sometimes feel like you are on the verge of something really big or important but you aren’t sure what it is?), heightened emotionality (e.g., Do you go through periods in which you feel over-stimulated by things or experiences that are normally manageable?), and heightened cognition (e.g., Do you ever feel like the mysteries of the universe are revealing themselves to you?). Previous research has found that the ASI is highly correlated with other measures of schizotypal personality traits, is elevated in participants at risk for the development of psychotic disorders, and is elevated in inpatients with a history of psychosis compared to inpatients without a history of psychosis (Cicero, et al., 2010). Moreover, the ASI has discriminant validity from other measures of schizotypal personality traits, as the ASI has been found to be correlated with measures reflecting increased subcortical dopamine, whereas other psychosis-proneness measures were not (Cicero et al., 2010). At the same time, there is very little if any overlap in item content between the types of experiences asked about on the ASI and the types of experiences on the PerMag or on other psychotic-like experiences scales (Cicero et al., 2010).

Self-Concept Clarity (SCC)

Self-concept clarity was measured with the self-concept clarity scale in Study 1 (SCCS; Campbell, 1990). The SCCS is a 12-item scale on which participants rate statements on a scale from 1 Strongly Agree to 5 Strongly Disagree (e.g., My beliefs about myself often conflict with one another). The SCCS has been found to be correlated with other measures of self-concept clarity including agreement of pairs of adjectives describing the self (Campbell, et al., 1996).

Psychotic-like Experiences

Perceptual aberration was measured with the Perceptual Aberration Scale (PerAb; Chapman, et al., 1978). The PerAb is a 35-item true-false scale that measures schizophrenic-like distortions in perceptions (e.g., “my hearing is sometimes so sensitive that ordinary sounds become uncomfortable”). Magical ideation was measured with the Magical Ideation Scale (MagicId; Eckblad & Chapman, 1983), a 30-item true-false scale designed to measure “beliefs in forms of causation that by conventional standards are invalid” (Eckbald & Chapman, 1983, p.215). For example, “I have worried that people on other planets may be influencing what happens on Earth.” The PerAb and MagicId have considerable support for the reliability and validity of their scores (for a review, see Edell, 1995). As commonly done in schizotypy research (Chapman, Chapman, Kwapil, Eckblad, & Zinser, 1994) scores on PerAb and MagicId were added together to form a single Perceptual Aberration/Magical Ideation (PerMag) score.

Social Anhedonia

Social Anhedonia was measured with the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (SocAnh; Chapman, et al., 1976). The SocAnh contains 40 true-false items that measure a lack of relationships and a lack of enjoyment derived from social interactions (e.g., “I am usually content just to sit alone, thinking and daydreaming”) and has been found to predict future development of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (e.g., Gooding, Tallent, & Matts, 2005). Previous research has found that SocAnh loads on the same factor as measures of the no close friends criterion of schizotypal personality disorder (Cicero & Kerns, 2010).

Infrequency

Participants also completed the Chapman Infrequency Scale, which measures invalid or careless responding. The scale includes items that should rarely be answered in the affirmative (e.g., I have never talked to someone wearing eyeglasses). Following convention in schizotypy research, participants answering “true” to three or more items were excluded from the analyses (Chmielewski, Fernandes, Yee, & Miller, 1995).

Procedure

Participants completed the study on a single occasion in an isolated room, which took approximately 60 minutes. Participants completed the Magical Ideation, Perceptual Aberration, Social Anhedonia, and Chapman Infrequency Scales mixed together. Then participants completed a battery of questionnaires including the Aberrant Salience Inventory, Self-Concept Clarity Scale, and filler items.

Results

Zero-Order Correlations

Since the studies in the current research include large samples, some correlations may reach conventional significance values but not be clinically meaningful. Due to the large number of correlations being examined, we used the Bonferroni method of correcting the p-value for multiple comparisons (Dunn, 1961). Thus, only correlations significant at the p < .001 level are presented and interpreted. As can be seen in Table 1, aberrant salience was associated with increased PerMag experiences. Self-concept clarity was negatively associated with aberrant salience and PerMag scores.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations for the Measures Used in Study 1

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aberrant Salience | ||||

| 1) Aberrant Salience Inventory | .90 | |||

| Self-Concept | ||||

| 2) SCCS | −.43* | .91 | ||

| Psychotic-Like Experiences | ||||

| 3) PerMag | .65* | −.41* | .89 | |

| Social Anhedonia | ||||

| 4) Social Anhedonia | .19* | −.28* | .31* | .82 |

| Mean | 14.18 | 38.27 | 11.35 | 8.66 |

| Standard Deviation | 6.80 | 5.04 | 9.04 | 5.17 |

p < .001, numbers on the diagonal represent Cronbach’s alpha. SCCS = Self-Concept Clarity Scale. PerMag = Combined Perceptual Aberration and Magical Ideation Scales.

Psychotic-like Experiences

In all of the regression analyses reported across studies, we first conducted regression diagnostics as suggested by Pedhazur (1997) to detect outliers. In order to treat outliers consistently across studies, data points with Cook’s Ds greater than .05 and leverage values greater than .04 were excluded from the analyses. Below we mention all instances where outliers were excluded.

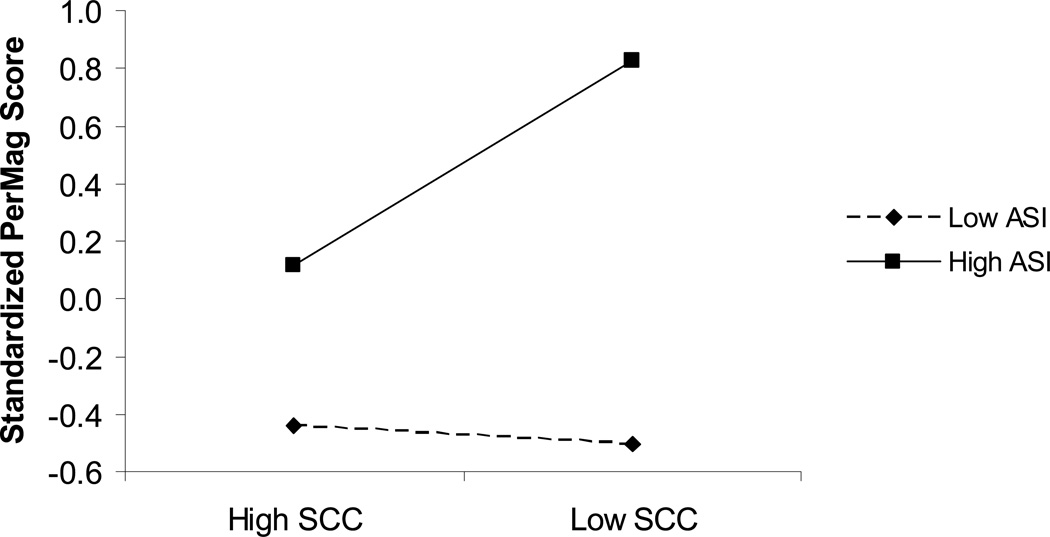

We then tested the prediction of social-cognitive models of psychotic-like experiences that an interaction between high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity predicts psychotic-like experiences. To test this interaction, ASI scores and SCCS scores were centered around their means and entered as step one of a hierarchical linear regression predicting PerMag. The product of ASI and SCCS scores was entered in step two of the analysis. Following Aiken & West (2001), to interpret the interaction, scores were calculated for +1 and −1 standard deviations from the mean for both aberrant salience and self-concept clarity. Aberrant salience and self-concept clarity interacted to predict PerMag (t (605) = 5.72, p < .001; See Figure 1, Table 2). Participants with high aberrant salience tended to have extreme levels of PerMag only if they had low levels of self-concept clarity as well, which is consistent with social-cognitive models of psychosis. To probe the interaction, we tested the simple slope of the relation between self-concept clarity and PerMag at high and low levels of aberrant salience (Hayes & Matthes, 2009). Self-concept clarity was associated with PerMag at 1 standard deviation above the mean on aberrant salience (t (605) = 9.15, p < .001), but not at 1 standard deviation below the mean (t (605) = 0.42, p =.67). This suggests that SCC is only associated with psychotic-like experiences when people also have high levels of aberrant salience.

Figure 1.

Perceptual Aberration/Magical Ideation as a Function of Aberrant Salience and Self-Concept Clarity in Study 1.

Table 2.

Regression Analyses for the Interaction between Aberrant Salience and Self-Concept Clarity in Predicting PerMag, Social Anhedonia, and PDI scores in Study 1 and Study 2.

| Study 1 |

Study 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PerMag | SocAnh | PerMag | PDI-Total Score | SocAnh | |

| Step 1 (ΔR2) | .46*** | .08*** | .36*** | .33*** | .09*** |

| ASI (β) | .58*** | .07 | .55*** | .52*** | .03 |

| SCCS (β) | −.17*** | −.25*** | −.13*** | −.12*** | −.28*** |

| Step 2 (ΔR2) | .03*** | .01 | .02*** | .01* | .00 |

| ASI X SCCS (β) | −.17*** | −.03 | −.13*** | −.07* | −.05 |

p < .001, ASI = Aberrant Salience Inventory, SCCS = Self-Concept Clarity Scale, PerMag = combined Perceptual Aberration Scale, Magical Ideation Scale, SocAnh = the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale, PDI = Peters Delusion Inventory.

Specificity of Moderation

To test if the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity was specific to psychotic-like experiences, we tested whether there was a significant interaction between the ASI and SCCS in predicting social anhedonia. There was not a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting social anhedonia (t (605) = 0.98, p = .33), which suggests that the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity is specific to psychotic-like experiences and not schizotypal personality in general. Examining the main effects revealed that SCCS is negatively related to social anhedonia, but the ASI is not.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 are consistent with several social-cognitive models of psychosis as well as phenomenological descriptions of psychotic-like experiences (Bell, et al., 2006; Freeman, 2007; Moller & Husby, 2000). Specifically, Study 1 found that participants with a combination of high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity had the highest levels of psychotic-like experiences. The probe of the interaction revealed that low self-concept clarity tended to be unrelated to psychotic-like experiences in people with low aberrant salience, but was strongly associated with increased psychotic-like experiences in people with high aberrant salience. This suggests that low SCC alone may not be sufficient to produce psychotic-like experiences, but may only do so in the presence of high aberrant salience. This finding is consistent with social-cognitive models of psychotic-like experiences that have predicted that self-relevant information processing interacts with aberrant salience or anomalous experiences to produce psychotic-like experiences (Bell, et al., 2006; Freeman, 2007).

In addition to being consistent with social-cognitive models of psychotic-like experiences, Study 1 found that the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity is specific to psychotic-like experiences. This was evident in that there was not a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting social anhedonia, a common negative symptom that is closely related to the schizotypal personality disorder criterion of a lack of close friends. This is also consistent with previous theoretical models of psychotic-like experiences which suggest that aberrant salience may only be related to positive symptoms, but not to negative symptoms (Kapur, 2003).

Study 2

The first goal of Study 2 was to replicate the results of Study 1 in an independent sample. This is important because Study 1 was the first study to test whether there was an interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting psychotic-like experiences. In addition, the second goal of Study 2 was to further test the specificity of the interaction by including a measure of delusion-like experiences, the Peters Delusions Inventory (PDI). We predicted that Study 2 would replicate the results of Study 1 and that aberrant salience and self-concept clarity would interact in the same pattern to predict PDI scores.

Method

Participants

Participants were 724 native English-speaking undergraduate students who took part in the study as partial fulfillment of a course requirement. Like in Study 1, participants were prescreened from a larger pool (n=2,244) by completing abbreviated versions of the Magical Ideation Scale (MagicId; Eckblad & Chapman, 1983), Perceptual Aberration Scale (PerAb; Chapman, et al., 1978), and Social Anhedonia Scale (SocAnh; Chapman, et al., 1976). Participants scoring two standard deviations above the mean or higher on these scales or a combined three standard deviations above the mean on MagicId and PerAb were recruited to the laboratory for an individual testing session. Participants who scored less than 0.5 standard deviations above the mean on all three scales were also recruited. Based on previously established cut-points (Kerns & Berenbaum, 2003), 60 participants met criteria for having high positive schizotypy and 72 met criteria for high negative schizotypy. Thirty-two participants were excluded for having Chapman Infrequency Scores of three or greater. Participants ranged from 18–26 years old, with an average age of 18.44 (SD = 0.84). Participants were 64% female, 84% White, 11% African-American, and 5% other.

Measures

Aberrant Salience

Like in Study 1, aberrant salience was measured with the Aberrant Salience Inventory (ASI; Cicero et al., 2010).

Self-Concept Clarity (SCC)

Like in Study 1, self-concept clarity was measured with the self-concept clarity scale (SCCS; Campbell, 1990).

Psychotic-like Experiences

Like in Study 1, perceptual aberration was measured with the Perceptual Aberration Scale (Chapman et al., 1978) and magical ideation was measured with the Magical Ideation Scale (Eckblad & Chapman, 1983).

In addition to PerMag, psychotic-like experiences were measured with the 21-item Peters Delusion Inventory (PDI; Peters, et al., 2004), which includes yes-no questions regarding delusion-like experiences (e.g., Have your thoughts ever been so vivid that you were worried other people would hear them?). As can be seen in Table 3, PDI scores were highly correlated with PerMag scores.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations for the Measures Used in Study 2

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aberrant Salience | |||||

| 1) Aberrant Salience | .86 | ||||

| Self-Concept Clarity | |||||

| 2) SCCS | −.34* | .86 | |||

| Psychotic-Like Experiences | |||||

| 3) PerMag | .59* | −.32* | .88 | ||

| 4) PDI-Total | .55* | −.31* | .61* | .74 | |

| Social Anhedonia | |||||

| 5) Social Anhedonia | .12* | −.29* | .23* | .19* | .85 |

| Mean | 15.63 | 37.82 | 12.82 | 6.10 | 7.34 |

| Standard Deviation | 6.12 | 9.42 | 9.61 | 3.18 | 5.70 |

p < .001, numbers on the diagonal represent Cronbach’s alpha. SCCS = Self-Concept Clarity Scale. PDI = Peters Delusion Inventory. PerMag = Combined Perceptual Aberration and Magical Ideation Scales.

Social Anhedonia

Like in Study 1, social anhedonia was measured with the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (SocAnh; Chapman, et al., 1976).

Infrequency

Participants also completed the Chapman Infrequency Scale as in Study 1.

Procedure

Participants completed the study on a single occasion in an isolated room. The entire study took approximately 60 minutes. First, participants completed the Aberrant Salience Inventory, Self-Concept Clarity Scale, and then the Magical Ideation, Perceptual Aberration, Social Anhedonia, and Chapman Infrequency Scales mixed together and called the “Survey of Attitudes and Experiences.” Then, participants completed the Peters Delusion Inventory.

Results

Zero-Order Correlations

As can be seen in Table 3, aberrant salience was associated with magical ideation, perceptual aberration, and PDI scores. It was negatively correlated with both measures of self-concept clarity. The SCCS was negatively correlated with magical ideation, perceptual aberration, PDI scores, and social anhedonia.

Aberrant Salience, Self-Concept Clarity, and Psychotic-like Experiences

We first tested the interaction between ASI and SCCS scores in predicting PerMag scores. Like in Study 1, mean centered ASI and SCC scores were entered in step 1 of a hierarchical linear regression predicting PerMag, and the product of these two terms was entered in step 2. Overall, there was a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity predicting PerMag (t (692) = −4.36, p < .001; See table 2). A probe of this interaction revealed that self-concept clarity was associated with PerMag when participants were one standard deviation above the mean on the ASI (t (692) = 6.01, p < .001), but not when participants were one standard deviation below the mean on the ASI (t (692) = −0.08, p = .93). This suggests that self-concept clarity is only related to PerMag at high levels of aberrant salience.1

In addition, we tested the same model to see if aberrant salience and self-concept clarity interacted to predict PDI scores. There was a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting PDI scores (t (691) = 2.01, p = .04, see Table 2). One outlier was excluded from these analyses. This participant had a cook’s distance value of .11 and a leverage score of .04, which suggests that the participant was an outlier in terms of residual distance from the slope and that this observation had an unduly large influence on the data (Pedhazur, 1997). Like PerMag, self-concept clarity was associated with PDI when participants had high ASI scores (t (691) = 4.26, p < .001), but not low ASI scores (t (691) = 1.37, p = .17). This suggests that self-concept clarity is only related to PDI scores at high levels of aberrant salience.1

Specificity of Moderation to Psychotic-like Experiences

To test if the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity was specific to psychotic-like experiences, we tested whether there was a significant interaction between the ASI and SCCS in predicting social anhedonia. There was not a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting social anhedonia (t (692) = −1.21, p = .22), which suggests that the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity is specific to psychotic-like experiences and not schizotypal personality in general. No outliers were identified. Examining the main effects revealed that SCCS is negatively related to social anhedonia (t (692) = −8.14, p < .001), but ASI is not (t (692) = −0.06, p = .95).

Specificity of Moderation to Aberrant Salience

In Study 2, the ASI was positively correlated with PerMag (r = .59). Although previous research has found that the ASI and PerMag measure distinct constructs (Cicero et al., 2010), this high correlation raises questions about the discriminant validity of the two scales. If ASI and PerMag measure the same construct, we would expect to find that PerMag would interact with SCC to predict the other measure of psychotic-like experiences, PDI scores, in the same manner that does the ASI. However, there was not a significant interaction between PerMag and SCC in predicting PDI scores (t (692) = 0.69, p < .49).

Discussion

Study 2 replicated the results of Study 1. First, there was a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity such that participants with high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity had the highest levels of psychotic-like experiences. Replication is especially important in the current research because Study 1 was the first study to show an interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting psychotic-like experiences. Second, Like Study 1, Study 2 did not find an interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting another facet of schizotypal personality disorder, social anhedonia. Finally, study 2 replicated the interaction with a separate measure of odd beliefs/magical thinking, the PDI. These results provide strong support that aberrant salience interacts with self-concept clarity to predict psychotic-like experiences and that this interaction is specific to psychotic-like experiences and not more generally to schizotypal personality disorder.

Study 3

Although Study 2 replicated and extended the results of study 1, one potential explanation for the finding that self-concept clarity interacts with aberrant salience to predict psychotic-like experiences is that the role of self-concept clarity can be explained by its overlap with neuroticism. For example, previous research has found that low self-concept clarity is associated with neuroticism (Campbell, et al., 1996). Similarly, there is a vast literature linking psychosis with a tendency to experience negative affect, particularly as a response to stressors (e.g., Berenbaum & Fujita, 1994; van Os, Kenis, & Rutten, 2010). Theorists have suggested that stress sensitivity, defined as an increased negative mood reaction to stress and assessed with measures of neuroticism, may be a suitable endophenotype for psychosis (see Myin-Germeys & van Os, 2007, for a review). Aberrant Salience may interact with negative affect, or neuroticism, such that people with high aberrant salience have psychotic-like experiences if they also have high neuroticism. This would suggest that it is not disturbances in self-processing that contribute to psychotic-like disturbances, but neuroticism. If the current result is specific to self-disturbances, then we would expect to replicate the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity found in Study 1 and Study 2 but not find an interaction between aberrant salience and neuroticism in predicting psychotic-like experiences.

In addition to testing the specificity of aberrant salience interacting with self-concept clarity to predict psychotic-like experiences, a goal of study 3 was to test whether the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity was specific to psychotic-like experiences. In Study 1 and Study 2, social anhedonia was used to examine specificity. To examine specificity in Study 3, we measured paranoia as an enduring trait. In people with psychotic disorders, persecutory delusions are the most common type of delusion (Appelbaum, Robbins, & Roth, 1999) and one of the models heavily relied upon in the current research is a model of persecutory delusions (Freeman, 2007). However, there are some important differences between paranoia as an enduring trait versus persecutory delusions. For instance, research suggests that paranoia as an enduring trait and an individual difference variable in the general population may be explained as a combination of high neuroticism and low agreeableness (e.g., Lynam & Widiger, 2001; Trull, Widiger, & Burr, 2001). In contrast, persecutory delusions, like psychotic-like experiences, may not be easily accounted for by extreme ends of normal personality traits (Tackett, Silberschmidt, Krueger, & Sponheim, 2008). Thus, persecutory delusions may share a common mechanism with other types of delusions (e.g., aberrant salience), but subclinical paranoia may not share this mechanism with perceptual aberration and magical ideation. At the same time, in at least 20 studies, previous schizotypal personality disorder research clearly shows that paranoia is distinct from a positive or cognitive-perceptual factor that includes PerMag (Bergman et al., 1996; e.g., Chmielewski & Watson, 2008; Cicero & Kerns, 2010; Fogelson et al., 1999; Fonseca-Pedrero, Paino-Pineiro, Lemos-Giraldez, Villazon-Garcia, & Muniz, 2009; and see Stefanis et al., 2004, for a review of additional studies). Moreover, some studies have found that subclinical paranoia is actually more strongly associated with negative schizotypy than with positive schizotypy (Cicero & Kerns, 2010; Stefanis, et al., 2004). Thus, Study 3 examined whether there was a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting paranoia. Paranoia serves as a more stringent test of the specificity of the interaction because paranoia is more strongly correlated with psychotic-like experiences than is social anhedonia (Stefanis, et al., 2004).

Method

Participants

Participants were 744 introductory to psychology students who participated in the study for partial completion of a course requirement. Like Study 1 and Study 2, participants were prescreened from a larger pool of participants (n= 2,197), by completing abbreviated versions of the Magical Ideation, Perceptual Aberration, and Social Anhedonia scales. According to previous research (Kerns & Berenbaum, 2003), 81 participants met criteria for high positive schizotypy and 60 participants met criteria for high negative schizotypy. Sixty-four participants were excluded for having Chapman Infrequency scores of three or greater. Participants ranged from 18–24 years old, with an average age of 18.47 (SD = 0.77). Participants were 61% female, 88% White, 4% African-American, and 10% other.

Measures

Aberrant Salience

Aberrant Salience was measured with the Aberrant Salience Inventory (Cicero, et al., 2010), like in Study 1 and Study 2.

Self-Concept Clarity

Self-concept clarity was measured with the Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell, 1990), like in Study 1 and Study 2.

Psychotic-Like Experiences

As in Study 1 and Study 2, psychotic-like experiences were measured with the Magical Ideation Scale (Eckblad & Chapman, 1983) and the Perceptual Aberration Scale (Chapman, et al., 1978)

Social Anhedonia

Like in Study 1 and Study 2, participants completed the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (Chapman, et al., 1976).

Neuroticism

Neuroticism was measured with the 10-item subscale of the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP; Goldberg, 1999). Participants rate items on a scale from 1 (very accurate) to 5 (very inaccurate). An example item is, “I get stressed out easily.” Previous research has found that the 10-item neuroticism subscale of the IPIP is highly correlated with other measures of neuroticism and has high internal consistency.

Paranoia

Paranoia was measured with the 8-item yes-no Suspiciousness subscale of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SQP-S; Raine, 1991; e.g., Do you sometimes get concerned that friends or coworkers are not really loyal or trustworthy?). In previous research, the SPQ-S has consistently been found to load with other measures of paranoia on a factor distinct from PerMag scales (e.g., Cicero & Kerns, 2010).

Infrequency

Participants completed the Chapman Infrequency Scale like in Study 1 and Study 2.

Procedure

As part of a larger study that included filler items, participants completed the Magical Ideation, Perceptual Aberration, Social Anhedonia, and Chapman Infrequency Scales mixed together and called the “Survey of Attitudes and Experiences.” Then participants completed the Aberrant Salience Inventory, the Self-Concept Clarity Scale, the Neuroticism subscale of the International Personality Item Pool, and the suspiciousness subscale of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire.

Results

First, we tested whether there was a significant three-way interaction between ASI, SCC, and Neuroticism scores in predicting PerMag scores (see Table 5). Mean centered ASI, SCC, and Neuroticism scores were entered in step 1 of a hierarchical linear regression. The three two-way interactions were entered in step 2, and the three-way interaction was entered in step 3. There was not a significant three-way interaction (t (675) = .72, p = .47). However, as in Study 1 and Study 2, there was a significant interaction between ASI and SCC scores in predicting PerMag (t (675) = 3.73, p <.001) such that participants with high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity had the highest levels of PerMag. There was not a significant interaction between aberrant salience and neuroticism in predicting PerMag (t (680) = 0.94, p = .34). Since there was not a significant two-way interaction between aberrant salience and neuroticism, we tested whether there were significant main effects for aberrant salience and neuroticism. Both aberrant salience (t (680) = 18.45, p < .001) and neuroticism (t (680) = 3.98, p = .03) uniquely contributed to the prediction of PerMag. Similarly, there was not a significant interaction between neuroticism and self-concept clarity in predicting PerMag (t (680) = 1.86, p = .06), but both SCC (t (680) = 9.14, p < .001) and neuroticism (t (680) = 2.35, p = .02) uniquely contributed to the prediction of PerMag. This suggests that the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity is specific to self-concept clarity, and not related to an interaction between aberrant salience and negative affectivity.

Table 5.

Regression Analyses for the Three-Way Interaction between the Aberrant Salience Inventory, Self-Concept Clarity Scale, and IPIP-Neuroticism Scale in Study 3.

| PerMag | |

|---|---|

| Step 1 (ΔR2) | .37*** |

| ASI (β) | .51*** |

| SCC (β) | −.18** |

| Neuroticism (β) | −.08* |

| Step 2 (ΔR2) | .01 |

| ASI X SCC (β) | −.12*** |

| ASI X Neuroticism (β) | .04 |

| Neuroticism X SCC (β) | .04 |

| Step 3 (ΔR2) | .01 |

| ASI X SCC X Neuroticism (β) | −.03 |

p < .001

p < .01, PerMag = combined Perceptual Aberration and Magical Ideation Scales, Neuroticism = the Neuroticism Subscale of the International Personality Item Pool.

Additionally, there was not a significant interaction between self-concept clarity and aberrant salience in predicting paranoia (t (680) = 0.54, p = .59). However, there were main effects for both self-concept clarity and aberrant salience in predicting paranoia (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Regression Analyses for the Interaction between Aberrant Salience and Self-Concept Clarity Predicting Paranoia in Study 3.

p < .001,

p < .01, SPQ-S = The Suspiciousness subscale of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire.

Discussion

Study 3 replicated the results of Study 1 and Study 2 by finding that there was a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting psychotic-like experiences. In addition, Study 3 found that there was not a significant interaction between aberrant salience and neuroticism in predicting psychotic-like experiences. Although neuroticism is associated with psychotic-like experiences, this association remains constant at all levels of aberrant salience. Thus, it appears that there is something specific about self-concept clarity that is distinct from negative affect that interacts with aberrant salience to predict psychotic-like experiences. This is consistent with previous theoretical models and phenomenological descriptions of psychosis, which suggest that it is a specific disturbance in the processing of self-relevant information that results in psychosis, rather than just a general feeling of negative affect (Freeman, 2007; Moller & Husby, 2000). The current research also found that self-concept clarity and aberrant salience did not interact to predict paranoia, which provides a more stringent test for the specificity of the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in predicting PerMag.

General Discussion

In three separate samples, the current research found that there was an interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity such that participants with high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity have the highest levels of psychotic-like experiences. This is consistent with social-cognitive models and phenomenological descriptions of psychotic experiences that have suggested a prominent role for both aberrant salience and self-concept clarity in psychotic-like experiences (e.g., Bell, et al., 2006; Bentall, et al., 2001; Freeman, 2007; Moller & Husby, 2000). These results were specific to psychotic-like experiences and not related to social anhedonia or paranoia. Additionally, the results of study 3 suggest that the interaction with aberrant salience is specific to self-concept clarity as the interaction between aberrant salience and neuroticism did not predict psychotic-like experiences.

As previously discussed, several researchers have suggested a central role for aberrant salience in psychotic-like experiences (e.g., Kapur, 2003; Roiser, et al., 2008). Previous research has found that the ASI is correlated with psychotic-like experiences in unselected samples, is elevated in people with high levels of schizotypal personality traits, and is higher in inpatients with a history of psychosis compared to inpatients without a history of psychosis (Cicero, et al., 2010). The current research extends these previous findings to suggest that aberrant salience alone may not be sufficient to produce psychotic-like experiences. Rather, the current research found that high levels of aberrant salience produced more extreme levels of psychotic-like experiences when those individuals also had unclear self-concepts. This is consistent with previous social-cognitive models which suggest that beliefs about the self and the world frame the response of the individual to an occurrence of aberrant salience (Freeman, 2007). Thus, an unclear self-concept may make an individual more likely to develop a psychotic-like explanation for an occurrence of aberrant salience.

The current research also has implications for the role of disturbances of self-relevant information processing in psychotic-like experiences. Recently, self-disturbances have received attention in the schizophrenia literature, particularly with respect to the prodrome (Lysaker & Lysaker, 2010), which is similar to schizotypal personality disorder (Seeber & Cadenhead, 2005). However, much of this research has been phenomenological or qualitative (e.g., Davidsen, 2009; Moller & Husby, 2000). As mentioned, one recent phenomenological study concluded that self-disturbances and aberrant salience were the two core variables associated with the development of psychosis (Moller & Husby, 2000). One strength of the current research is that self-disturbance was measured with a quantitative measure while most research in this area has been qualitative in nature. The probe of the interaction suggests that self-concept clarity is only related to psychotic-like experiences at high levels of aberrant salience.

One area for future research could be to examine self-disturbances in other quantitative ways. For example, previous research suggests that people with psychosis show a lack of coherence in personal narratives of their life stories (Lysaker, Clements, Plascak-Hallberg, Knipscheer, & Wright, 2002), have less clear memories of self-related past events, more difficulty in generating specific future events, and that these deficits were associated with positive but not negative symptoms (D'Argembeau, Raffard, & Van der Linden, 2008). Additionally, psychosis has been linked to other deficits in the processing of self-relevant information such as monitoring of internally vs. externally generated speech (Johns, Gregg, Allen, & McGuire, 2006), sense of self agency (Lysaker, Wickett, Wilke, & Lysaker, 2003), and insight into mental illness (e.g., Baier, 2010). Future research could examine whether these impairments in self-processing also interact with aberrant salience to predict psychotic-like experiences.

In addition to being consistent with models of psychotic-like experiences, the current research is consistent with models of normal belief formation. For example, the Meaning Maintenance Model (Heine, Proulx, & Vohs, 2006) posits that people reinstate meaning after a threat to meaning. A meaning threat may include a threat to a person’s worldview or self-esteem. Consistent with this, aberrant salience involves irrelevant stimuli being imbued with significance and is thought to trigger a search for an explanation (Kapur, 2003). At the same time, low self-concept clarity may itself be a threat to meaning that could result in people being more likely to seek meaning for experiences. In one study, Proulx and Heine (2009) had participants write an essay arguing against the unity of their self-concepts, which may be analogous to experimentally causing low self-concept clarity. They found that participants in this condition were more likely to perceive meaning in stimuli following this manipulation. This suggests that occurrences of aberrant salience might be especially likely to be perceived as meaningful if people also have low self-concept clarity, which may lead to psychotic symptoms.

The current research suggests several areas for future research. One limitation of the current research is that it is correlational and thus could not establish whether the combination of high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity actually causes psychotic-like experiences. This could be addressed in at least two ways. For example, future research could follow participants longitudinally and establish the temporal precedence of aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity before the development of psychotic-like experiences. If having high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity causes psychotic-like experiences, then we would expect participants to report this them to reporting psychotic-like experiences.

The proposed interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity may make more intuitive sense when explaining delusion-like beliefs than hallucination-like experiences. However, Kapur (2003) suggested that hallucinations may arise on a similar path in which salience is aberrantly attributed to perceptual aberrations or anomalous experiences. Such experiences, which may be ephemeral in people with low aberrant salience, capture attention and continue to occur more frequently in people with high aberrant salience. Garety et al. (2001) suggest that psychotic-like experiences only become psychotic symptoms when the individual misattributes the source of the experience to something external. Similarly, low self-concept clarity may exacerbate this source misattribution. Thus, high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity may fuel a feedback loop in which hallucination-like experiences capture attentional resources, in turn leading to more hallucination-like experiences. Future research could continue to examine the applicability of the interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity to hallucination-like experiences in addition to delusion-like experiences.

Another issue for future research is to extend these results beyond undergraduate populations. However, one methodological problem in examining social-cognitive models of psychosis is that people with psychotic disorders typically take antipsychotic medications that block dopamine receptors. This might be especially important for examining the construct of aberrant salience because aberrant salience is thought to be related to dysregulated dopamine (Kapur, 2003). Kapur has argued that, since antipsychotic medications block dopamine receptors, their main function in reducing psychotic-like experiences is to eliminate occurrences of aberrant salience. The current research over-sampled participants with a high level of psychotic-like experiences that are associated with future psychotic disorder (Chapman et al., 1994). This allowed us to examine the social-cognitive mechanisms associated with psychotic-like experiences while removing some of the confounds associated with research on patient populations (Neale & Oltmanns, 1980).

Although the current research examined psychotic-like experiences and not full-blown psychosis, we think the current studies can provide useful information on the nature of psychosis. Previous research has found that measures of psychotic-like experiences are strongly correlated with ratings of positive symptoms in people with schizophrenia (Cochrane, Petch, & Pickering, 2010), and that psychotic-like experiences measured with the Perceptual Aberrant/Magical Ideation Scales are very similar to psychotic experiences in individuals who go on to develop psychotic-disorders (see Kwapil, Chapman, & Chapman, 1999, for a review). In addition to not including people with full-blown psychosis, one limitation could be that the participants in the current research were undergraduates. However, research suggests that the levels of psychotic-like experiences and personality disorders in undergraduate populations is similar to that of the general population (Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007). Despite these findings in previous research, there may be meaningful differences between subclinical psychotic-like experiences in college students and psychotic experiences in people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. For example, college students may be higher functioning than other people with schizotypal personality disorder or psychosis by virtue of functioning well enough to be enrolled in college. Thus, future research could examine whether similar results are found in prodromal, first-break, and chronic schizophrenia samples. This would answer the question of whether these experiences (i.e., high aberrant salience and low self-concept clarity) are specific to the pre-psychotic or prodromal phase of the disorder or whether these relations hold true in people with schizophrenia or with other psychotic disorders as well.

Table 4.

Bivariate Correlations for the Measures Used in Study 3

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Aberrant Salience Inventory | .90 | |||||

| 2) SCCS | −.33* | .91 | ||||

| 3) PerMag | .59* | −.37* | .85 | |||

| 4) Neuroticism | .09 | −.30* | .19* | .88 | ||

| 5) SPQ-Suspiciousness | .46* | −.40* | .45* | .24* | .72 | |

| 6) SocAnh | .17* | −.26* | .41* | .15* | .39* | .81 |

| Mean | 13.94 | 37.32 | 13.77 | 30.24 | 2.62 | 7.24 |

| Standard Deviation | 7.11 | 8.10 | 10.15 | 7.08 | 2.21 | 5.28 |

p < .001, numbers on the diagonal represent Cronbach’s Alpha, SCCS = Self-Concept Clarity Scale, PerMag = combined Perceptual Aberration and Magical Ideation Scales, SPQ = Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire, SocAnh = Social Anhedonia Scale.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported by NIMH Grants MH072706 and MH086190, National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA022405, and a MU Research Board grant.

Footnotes

There was a significant interaction between aberrant salience and self-concept clarity predicting PDI delusional distress (t (692) = −3.66, p < .001) and PDI preoccupation (t (692) = −2.69, p < .001) subscale scores. However, the interaction was not significant in predicting conviction (t (692) = −1.02, p = .31).

References

- Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Alliger R, Miller D, Flaum M. Symptoms of schizophrenia. Methods, meanings, and mechanisms. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:341–351. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Roth LH. Dimensional approach to delusions: comparison across types and diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1938–1943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AP. DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th, Text Revision ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baier M. Insight in schizophrenia: a review. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2010;12(4):356–361. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive approaches to schizophrenia: theory and therapy. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:577–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell V, Halligan PW, Ellis HD. Explaining delusions: a cognitive perspective. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2006;10(5):219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentall RP, Corcoran R, Howard R, Blackwood N, Kinderman P. Persecutory delusions: a review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:1143–1192. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Fujita F. Schizophrenia and personality: exploring the boundaries and connections between vulnerability and outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(1):148–158. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman AJ, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, Aronson A, Marder D, Silverman J, Siever LJ. The factor structure of schizotypal symptoms in a clinical population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22:501–509. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine's role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MB., Jr Pathogenesis of acute schizophrenic psychosis. An experimental approach. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1968;19:348–355. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1968.01740090092009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD. Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59(3):538–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, Lehman DR. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Kwapil TR, Eckblad M, Zinser MC. Putatively psychosis-prone subjects 10 years later. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:171–183. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:374–382. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Body-image aberration in Schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;87:399–407. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.87.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Fernandes LO, Yee CM, Miller GA. Ethnicity and gender in scales of psychosis proneness and mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:464–470. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Watson D. The heterogeneous structure of schizotypal personality disorder: item-level factors of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire and their associations with obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, dissociative tendencies, and normal personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:364–376. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero DC, Kerns JG. Multidimensional factor structure of positive schizotypy. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2010;24(3):327–343. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero DC, Kerns JG, McCarthy DM. The Aberrant Salience Inventory: A new measure of psychosis proneness. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22(3):688–701. doi: 10.1037/a0019913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane M, Petch I, Pickering AD. Do measures of schizotypal personality provide non-clinical analogues of schizophrenic symptomatology? Psychiatry Research. 2010;176(2-3):150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau A, Raffard S, Van der Linden M. Remembering the past and imagining the future in schizophrenia. Journal of abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):247–251. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen KA. Anomalous self-experience in adolescents at risk of psychosis. Clinical and conceptual elucidation. Psychopathology. 2009;42(6):361–369. doi: 10.1159/000236907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons among means. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1961;56:52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Magical ideation as an indicator of schizotypy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:215–225. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edell WS. The psychometric measurement of schizotypy using the Wisconsin Scales of Psychosis-Proneness. In: Miller G, editor. The behavioral high-risk paradigm in psychopathology. New-York: Pringer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A, Vanable PA. Paranoia and self-consciousness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:129–138. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogelson DL, Nuechterlein KH, Asarnow RF, Payne DL, Subotnik KL, Giannini CA. The factor structure of schizophrenia spectrum personality disorders: signs and symptoms in relatives of psychotic patients from the UCLA family members study. Psychiatry Research. 1999;87:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Paino-Pineiro M, Lemos-Giraldez S, Villazon-Garcia U, Muniz J. Validation of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief Form in adolescents. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;111(1-3):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D. Psychological formulation of early episodes of psychosis: A cognitive model. In: Birchwood D, Fowler D, Jackson C, editors. Early intervention in psychosis: A guide to concepts, evidence, and interventions. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2000. pp. 101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D. Suspicious minds: the psychology of persecutory delusions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:425–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Freeman D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(2):189–195. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. A broad-bandwidth, public health domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. Personality psychology in Europe. 1999;Vol. 77:7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding DC, Tallent KA, Matts CW. Clinical status of at-risk individuals 5 years later: further validation of the psychometric high-risk strategy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:170–175. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Feldon J, Rawlins JN, Hemsley DR, Smith AD. The neuropsychology of schizophrenia. Behavior and Brain Research. 1991;14:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Reseach Methods. 2009;41(3):924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Proulx T, Vohs KD. The meaning maintenance model: on the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10(2):88–110. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley DR. The disruption of the 'sense of self' in schizophrenia: potential links with disturbances of information processing. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1998;71(Pt 2):115–124. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, Murray RM, Valli I, Tabraham P, Grasby PM. Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):13–20. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns LC, Gregg L, Allen P, McGuire PK. Impaired verbal self-monitoring in psychosis: effects of state, trait and diagnosis. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(4):465–474. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Paradise AW, Whitaker DJ, Wheatman SR, Goldman BN. Master of one's psychological domain? Not likely if one's self-esteem is unstable. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1297–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Berenbaum H. Aberrant semantic and affective processing in people at risk for psychosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:728–732. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Berenbaum H. The relationship between formal thought disorder and executive functioning component processes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR, Chapman LJ, Chapman J. Validity and usefulness of the Wisconsin Manual for Assessing Psychotic-like Experiences. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25:363–375. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A. Dopamine as the wind of the psychotic fire: new evidence from brain imaging studies. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1999;13:358–371. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Widiger TA. Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: an expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:401–412. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Clements CA, Plascak-Hallberg CD, Knipscheer SJ, Wright DE. Insight and personal narratives of illness in schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):197–206. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.197.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Lysaker JT. Schizophrenia and alterations in self-experience: a comparison of 6 perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(2):331–340. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Wickett AM, Wilke N, Lysaker J. Narrative incoherence in schizophrenia: the absent agent-protagonist and the collapse of internal dialogue. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2003;57(2):153–166. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2003.57.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller P, Husby R. The initial prodrome in schizophrenia: searching for naturalistic core dimensions of experience and behavior. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26:217–232. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(4):409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale JM, Oltmanns TF. Schizophrenia. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Parnas J, Handest P, Saebye D, Jansson L. Anomalies of subjective experience in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108:126–133. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur EJ. Multiple regression in behavioral research: explanation and prediction. 3rd ed. Toronto, Ontario: Wadsworth Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peters ER, Joseph S, Day S, Garety P. Measuring delusional ideation: the 21-item Peters et al. Delusions Inventory (PDI) Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(4):1005–1022. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx T, Heine SJ. Connections from Kafka: exposure to meaning threats improves implicit learning of an artificial grammar. Psychological Science. 2009;20(9):1125–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raballo A, Saebye D, Parnas J. Looking at the Schizophrenia Spectrum Through the Prism of Self-disorders: An Empirical Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1991;17:555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiser JP, Stephan KE, Ouden HE, Barnes TR, Friston KJ, Joyce EM. Do patients with schizophrenia exhibit aberrant salience? Psychological Medicine. 2008:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber K, Cadenhead KS. How does studying schizotypal personality disorder inform us about the prodrome of schizophrenia? Current Psychiatry Reports. 2005;7(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. Dopamine receptors and the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Synapse. 1987;1:133–152. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanis NC, Smyrnis N, Avramopoulos D, Evdokimidis I, Ntzoufras I, Stefanis CN. Factorial composition of self-rated schizotypal traits among young males undergoing military training. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:335–350. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson DA, Wood JV, Doxey JR. In search of clarity: self-esteem and domains of confidence and confusion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34(11):1541–1555. doi: 10.1177/0146167208323102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Silberschmidt AL, Krueger RF, Sponheim SR. A dimensional model of personality disorder: incorporating DSM Cluster A characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:454–459. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Burr R. A structured interview for the assessment of the Five-Factor Model of personality: facet-level relations to the axis II personality disorders. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:175–198. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, Vollebergh W. Prevalence of psychotic disorder and community level of psychotic symptoms: an urban-rural comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:663–668. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BP. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):203–212. doi: 10.1038/nature09563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]