Abstract

In rats, a critical period exists around postnatal day (P) 12-13, when an imbalance between heightened inhibition and suppressed excitation led to a weakened ventilatory and metabolic response to acute hypoxia. An open question was whether the two genders follow the same or different developmental trends throughout the first 3 postnatal weeks and whether the critical period exists in one or both genders. The present large-scale, in-depth ventilatory and metabolic study was undertaken to address this question. Our data indicated that: 1) the ventilatory and metabolic rates in both normoxia and acute hypoxia were comparable between the two genders from P0 to P21; thus, gender was never significant as a main effect; and 2) the age effect was highly significant in all parameters studies for both genders, and both genders exhibited a significantly weakened response to acute hypoxia during the critical period. Thus, the two genders have comparable developmental trends, and the critical period exists in both genders in rats.

Keywords: carbon dioxide production, gender difference, hypoxia, oxygen consumption, respiration

1. Introduction

Postnatal respiratory development in rats does not follow a smooth path, but rather, a critical period exists around postnatal days (P) 12-13, when a striking and transient imbalance between enhanced inhibition and suppressed excitation is evident both neurochemically within the respiratory network (Liu & Wong-Riley, 2002, 2005, 2010c; Wong-Riley & Liu, 2005) as well as electrophysiologically in hypoglossal motoneurons (Gao et al., 2011). Other concomitant changes include a precipitous fall in the expression of several serotonergic neurochemicals (Liu & Wong-Riley, 2008, 2010a, 2010b), a switch in GABAA receptor subunit dominance (Liu & Wong-Riley, 2004, 2006), a switch in dominance from a chloride importer (NKCC1) to a chloride exporter (KCC2) (Liu & Wong-Riley, 2012), and a significant reduction in the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its high-affinity tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) (Liu & Wong-Riley, 2013) in multiple respiratory-related nuclei. During this time, the animals’ ventilatory and metabolic responses to hypoxia are also at their weakest (Liu et al., 2006, 2009; Wong-Riley & Liu, 2008). These findings, in which male and female data were combined, have special implication for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), whose peak incidence is between the 2nd and 4th postnatal months, strongly implicating a critical period of postnatal development (Filiano & Kinney, 1994; Mage & Donner, 2009).

An open question that deserves some attention is whether both male and female animals follow the same or different developmental trends and whether the critical period exists in one or both genders. This is of clinical relevance, as the prevalence of SIDS is higher in male than in female infants (Mage and Donner, 2009). A recent report (Holley et al., 2012) stated that “P10-15 includes a critical developmental period in male but not female rats”. As the study grouped animals into two-day pairs and concentrated only on P10-15 animals, the question remains as to whether the two genders differ throughout the first 3 postnatal weeks or whether the disparity occurs only during the critical period. Based on our initial analysis of a lack of gender difference, we deemed it necessary to rigorously test our hypothesis that the two genders exhibit comparable developmental trends throughout the first 3 postnatal weeks and that the critical period exists in both genders.

Our goal was to undertake a large-scale, in-depth study to compare the ventilatory and metabolic responses of male versus female rats in both normoxia and acute hypoxia daily during the entire first three postnatal weeks. In addition to segregating our previous large-scale data (Liu et al., 2009) into the two genders and analyzing them each day from P0 to P21, we added many more animals to increase the N of each gender at each age and to substantially strengthen the statistical power.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

All experiments and animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health), and all protocols were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee.

A total of 302 Sprague-Dawley rats (parents purchased from Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) from 30 litters were used in this study, including data of 139 rats from 16 litters published previously (Liu et al., 2009) in which male and female data were combined but are now segregated by gender and re-analyzed, as well as 163 new rats from 14 new litters. The litter size was typically 10-15 pups. All rat pups used in the current study were born between 10 am and 4 pm, and all ventilatory and metabolic data were collected between those two time points during the day. The test days were staggered among the animals such that every single day between P0 (day of birth) and P21 was covered. For each of the days from P0 to P21, animal numbers ranged from 10 rats from 8 litters to 26 rats from 19 litters for each gender (see Table 1). Ten male and 10 female rats from 3 litters starting at P10-11 and exposed to acute hypoxia only once were compared with other litters (starting at P0-4 and exposed to hypoxia every 5th day) to determine if repeated hypoxic exposure (every 5th day for 7 min) would affect the latter's hypoxic ventilatory and metabolic responses. Another 17 male rats from 11 litters and 15 female rats from 12 litters were studied daily under normoxia to serve as a reference for the normoxic data obtained from pups examined every fifth day under normoxia followed by 7 min of hypoxia. For younger animals, gender distinction was based on the distance between the anus and the urethra (with the distance being further apart in males than in females) as well as on markings of developing nipples in female pups.

Table 1.

Animal and litter numbers

| Postnatal day (P) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(N) | 16 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 14 | 11 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 22 | 26 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 14 | 17 | 14 | 21 |

| M(L) | 14 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 17 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 14 |

| F(N) | 16 | 20 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 11 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 17 | 12 | 19 |

| F(L) | 12 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 9 | 8 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 18 |

M(N), number of male rats in each age group; M(L), number of litters (to which male rats belonged) in each age group; F(N), number of female rats in each age group; F(L), number of litters (to which female rats belonged) in each age group.

2.2. Ventilatory and metabolic measurements during normoxia and acute hypoxia

Ventilatory and metabolic measurements were performed according to a protocol described previously (Liu et al., 2009). Briefly, O2 fraction, CO2 fraction, and ventilation (including respiratory frequency (f), tidal volume (VT), and their product minute ventilation (V̇E) were determined in awake rat pups placed in an airtight 150 ml plastic syringe with flow through at 150 ml/min. The O2 fraction, CO2 fraction, pressure, relative humidity (RH), and temperature (T) signals were digitized with a data acquisition device. Each animal was tested first in room air for 6 minutes and then subjected to 7 minutes of hypoxia (10% O2 balanced with 90% nitrogen N2). Each pup was exposed to a 7-min hypoxia only every fifth day to prevent adverse cumulative effect of hypoxia (Liu et al., 2006, 2009).

Before and during each experiment, the animals’ body temperature was maintained at a level comparable to their starting temperature when they were first taken out of the cage, i.e., 34-38.5°C (depending on the age). This was achieved by placing the animals on a moderately-heated heating pad on the floor of the plethysmograph and their body temperature was monitored before and after each experiment. The ambient temperature of the chamber was maintained at 26-28°C. Gas calibration was taken before and after each animal's experiment with known gas mixture. For recording of ventilation, the system was calibrated by applying 0.1 ml of air into the plethysmographic chamber ten times before and after each animal's recording (Liu et al., 2009). Rectal temperature of each animal was measured before and after each recording. Adjustments of calibration with different breathing frequency and body volume were extensively addressed in our previous study (Liu et al., 2009).

2.3. Data collection and statistical analyses

Metabolic rates, oxygen consumption (V̇O2) and carbon dioxide production (V̇CO2) were calculated by applying the Fick Principle (Fishman et al., 1952). VT, f, and V̇E were calculated by using the formulae of Drorbaugh & Fenn (1955), which takes into account the RH, temperature, and pressure of the chamber. Thus, the ratios of V̇E/V̇O2 and V̇E/V̇CO2 as well as respiratory quotient (V̇CO2/V̇O2) were calculated. The values were grouped into 30-sec bins during the 5th and 6th min in normoxia and 6th and 7th min in hypoxia, when breathing and gas concentrations were more stable (see Liu et al., 2009, Fig. 1A and 1B), and expressed as the mean of the last two min either in 6 min normoxia or 7 min hypoxia ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A total of 35 parameters (f, VT, V̇E, V̇O2, V̇CO2 [except for f, each of the parameters were non-normalized as well as normalized to body weight], V̇E/V̇O2, V̇E/V̇CO2, and respiratory quotient [RQ] in normoxia and in hypoxia, the ratio of each parameter in hypoxia versus that in normoxia, body weight, and body temperature in normoxia and hypoxia) and 22 ages (P0 to P21) were analyzed.

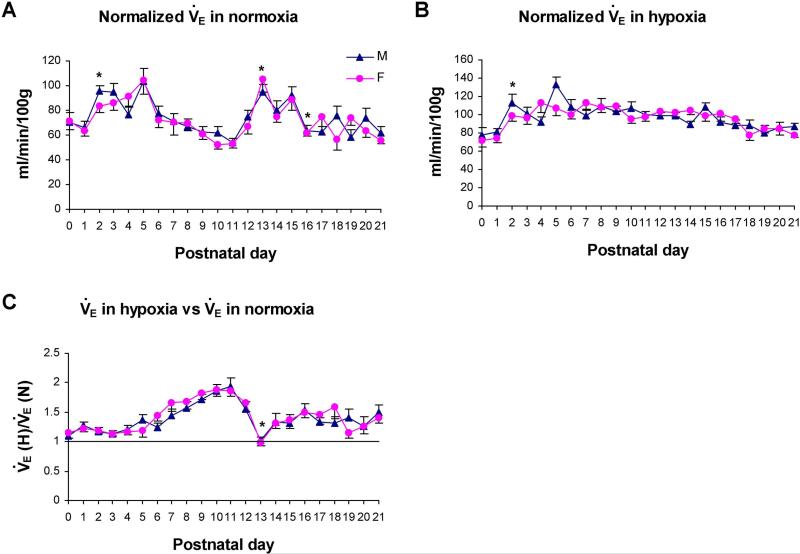

Fig. 1. Minute ventilation (V̇E) in normoxia and hypoxia (10% O2 for 7 min).

A. Normalized (to 100 g body weight) V̇E in normoxia from P0 to P21. Both genders had significant rises at P2 and P13 and a significant fall at P16. B. Normalized V̇E in hypoxia from P0 to P21. Both genders showed a significant rise at P2. C. V̇E in hypoxia (V̇E (H)) versus V̇E in normoxia (V̇E (N)) from P0 to P21. A significant fall in the ratio was found at P13 in both genders. No gender difference was found at any age. Values expressed here and in subsequent figures represent the mean of raw data ± standard errors of the means (SEM), whereas values in normoxia were expressed as 1 when compared with those in hypoxia. Statistical significance was based on mixed model analysis with false discovery rate (FDR). *, P < 0.05; significance for both genders between one age group and its immediately adjacent younger age group. M, male rats, F, female rats.

For statistical analysis, a generalized Linear Mixed Model analysis was used to account for clustering in the data and to control for repeated observations of each animal and multiple testing. A random effect was used to account for repeated observations of the same animals, and fixed effects were used to model the effects of Litter, Age (categorical, with 21 degrees of freedom), Gender, and Age-by-Gender interaction. Examination of residuals showed non-normality, with a tendency towards larger error for larger values, and a log-transform was applied to the data to correct the residual error to normality. Least-square means estimates were used to generate plots and numerous post-hoc comparisons. Results were exponentiated (reverse-transformed) and reported on the original scale. Multiple testing was controlled by applying a 5% False Discovery Rate (FDR, which expects that 5% of all significant results will be falsely significant; Benjamini-Hochberg, 1995), including 770 comparisons of Gender at each Age (22 age groups times 35 parameters), 735 comparison of day-to-day changes (gender averaged; 21 pairs of adjacent age groups times 35 parameters), 735 day-to-day Gender interactions (21 pairs of adjacent age groups times 35 parameters). This last group could also be described as the simple Age-by-Gender interaction-effects on any two consecutive days. Applying the FDR to these 2,240 comparisons, raw P-values less than 0.00126 met the threshold for a 5% FDR. A 5% significance level was used. The analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

All figures shown represented the raw data (mean ± SEM), but all statistical significance shown in the figures was based on the mixed model analysis with FDR.

3. Results

In general, both genders exhibited comparable developmental trends in ventilatory and metabolic responses during normoxia and under hypoxia, in agreement with our previous reports in which male and female data were combined (Liu et al., 2006; 2009). When normoxic data from animals exposed to hypoxia every 5th day for 7 minutes were compared to those from age-matched animals exposed to normoxia only, no significant difference was found. Likewise, there was no significant difference in the hypoxic response between animals exposed to hypoxia every 5th day and age-matched animals exposed to hypoxia only once. Thus, exposure to hypoxia every 5th day for 7 min did not have a lasting effect on the animals’ ventilatory and metabolic responses both in normoxia and hypoxia.

The linear mixed model analysis indicated that the age effect was significant in all parameters for both genders (P < 0.0022 for all), and the gender effect was not significant in all parameters (P > 0.05), whereas the age-by-gender effect was significant for only 2 of the 35 parameters (P < 0.05). The False Discovery Rate (FDR) analysis indicated significant age effect in 56 pairwise comparisons (involving 23 parameters) for both genders when one age group was compared to its immediately adjacent younger age group, that gender effect was not significant in all parameters, and that only two parameters showed significance in age-by-gender interaction, both of which occurred soon after birth (one at P1 and one at P2). All P values described below reflect mixed model analysis with FDR.

3.1. Postnatal developmental trends of frequency (f) during normoxia and hypoxia

During normoxia, the frequency of ventilation (f) in both genders rose significantly and peaked at P13 (P < 0.05 for both genders), followed by a decline until P21. When f responses to hypoxia were compared to those in normoxia, both genders exhibited a plateau from P0 to P4-5 and a gradual rise until P9-10, followed by a decrease at P12 and a significant reduction at P13 (P < 0.05 for both genders), with a plateau thereafter until P21 (data not shown).

3.2. Postnatal developmental trends of tidal volume (VT) during normoxia and hypoxia

During normoxia and hypoxia, VT values in both genders increased progressively from P0 to P21. When VT was normalized to body weight (per 100 g), the values in normoxia for both genders declined gradually from P0 to P10-11, followed by a plateau until P21. Under hypoxia, both genders exhibited a relatively constant trend. When VT responses to hypoxia were compared to those in normoxia, both genders exhibited a relatively stable trend from P0 to P13, followed by a gradual rise until P20 (data not shown).

3.3. Postnatal developmental trends of minute ventilation (V̇E) during normoxia and hypoxia

When V̇E was normalized to body weight, a significant rise was found in both genders at P2 (P < 0.05) under normoxia (due mainly to an increases in VT). This was followed in both genders by a gradual decline from P5 to P11, a significant rise at P13 (P < 0.05), a significant decline at P16 (P < 0.05), and fluctuations thereafter until P21 (Fig. 1A). Between P17 and P21, the pattern of fluctuation in females was one-day ahead of males. Under hypoxia, normalized V̇E in both genders had a significant rise at P2 (P < 0.05), but plateaued thereafter until P21, with greater fluctuations in males than in females (Fig. 1B). When V̇E responses in hypoxia were compared to those in normoxia, both genders showed a plateau from P0 to P5-6, then a gradual rise until P11 followed by a significant fall at P13 (P < 0.05 for both genders), with a slight rise and a plateau thereafter until P21 (Fig. 1C). No significant gender difference was found at any time point.

3.4. Postnatal developmental trend of oxygen consumption (V̇O2) in normoxia and hypoxia

When V̇O2 was normalized to body weight, both genders exhibited a significant rise at P2 in normoxia (P < 0.05) followed by a plateau until P7, then a decline from P7 to P9 (in females) or to P10 (in males) before plateauing until P21 (Fig. 2A). Under hypoxia, normalized V̇O2 again exhibited a significant rise at P2 in both genders (P < 0.05), followed by a plateau before a fall at P5 (in males) or at P5-6 (in females), a significant fall in both genders at P13 (P < 0.05), and another plateau until P21 (Fig. 2B). When hypoxia V̇O2 responses were compared to normoxic ones, both genders showed a plateau from P0 to P5-6, a gradual rise to peak at P9 (in females) or P10 (in males), a significant fall at P13 in both genders (P < 0.05), and a plateau thereafter until P21 (Fig. 2C). No significant gender difference was found at any time point.

Fig. 2. Postnatal developmental trend of oxygen consumption (V̇O2) and carbon dioxide production (V̇CO2) in normoxia and hypoxia.

A. Normalized V̇O2 in normoxia from P0 to P21. Both genders exhibited a significant day-to-day rise at P2. B. Normalized V̇O2 in hypoxia from P0 to P21. Both genders showed a significant rise at P2 and a significant fall at P13. C. V̇O2 in hypoxia (V̇O2 (H)) versus that in normoxia (V̇O2 (N)) from P0 to P21. Both genders exhibited a significant fall at P13. D. Normalized V̇CO2 in normoxia from P0 to P21. Both genders exhibited significant day-to-day rises at P1 and P2. E. Normalized V̇CO2 in hypoxia from P0 to P21. Both genders showed significant rises at P1 and P2. F. V̇CO2 in hypoxia (V̇CO2 (H)) versus that in normoxia (V̇CO2 (N)). Both genders exhibited significant falls at P2 and P13 as well as a significant rise at P9. *, P < 0.05; significance for both genders between one age group and its immediately adjacent younger age group.

3.5. Postnatal developmental trend of carbon dioxide production in normoxia and hypoxia

When V̇CO2 was normalized to body weight, the values in normoxia for both genders increased significantly at P1 and P2 (P < 0.05), and declined gradually from P4 (in males) or P5 (in females) to P9 (in females) or P10 (in males), followed by a plateau until P21 (Fig. 2D). Under hypoxia, normalized V̇CO2 increased significantly in both genders at P1 and P2 (P < 0.05), followed by a relative plateau until P21 (Fig. 2E). A fall in value from P4 to P5 in males was one day ahead of that in females. When V̇CO2 responses to hypoxia were compared to those in normoxia, both genders showed an initial high value at P0-P1 followed by a significant fall at P2 (P < 0.05) that remained low and fluctuated until a significant rise at P9 in both genders (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2F). In females, the ratio peaked at P9, two days earlier than that in males. Both genders exhibited a significant fall in the ratio at P13 (P < 0.05) followed by a rise at P14 and a plateau until P21 (Fig. 2F). No significant gender difference was found at any time point.

3.6. Postnatal changes in V̇E/V̇O2 and V̇E/V̇CO2 ratios in normoxia and hypoxia

During normoxia, the V̇E/V̇O2 ratio in both genders attained its highest value at P0, then declined gradually to its lowest level at P4 followed by a relative plateau until P21, except for a sudden rise at P13 (significant when data from both genders were combined) and a fall at P14 (Fig. 3A). Under hypoxia, the ratio was relatively constant in both genders throughout the 3 weeks, except that the value in males was significantly higher than that in females at P1 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). The ratio peaked at P5 in males, a day earlier than that in females. When V̇E/V̇O2 ratios in hypoxia were compared to those in normoxia, the values were above 1 in both genders at all ages except for P0 and P13, when they were close to or slightly below 1 (Fig. 3C). The fall at P13 was significant when data from both genders were combined. No significant gender difference was found at any age tested.

Fig. 3. Postnatal changes in V̇E/V̇O2 and V̇E/V̇CO2 ratios in normoxia and hypoxia.

A. V̇E/V̇O2 ratios in normoxia (V̇E(N)/V̇O2(N)) from P0 to P21. No significant gender difference was found at any age. B. V̇E/V̇O2 in hypoxia (V̇E (H)/V̇O2 (H)) from P0 to P21. A significant age-by-gender interaction was found at P1, when the male value was much higher than that of the female. C. V̇E/V̇O2 in hypoxia versus that in normoxia from P0 to P21. The ratio was lowest at P0 and P13. No significant gender difference was found at any age. D. V̇E/V̇CO2 ratios in normoxia (V̇E (N)/V̇CO2 (N)) from P0 to P21. No significant gender difference was found at any age. E. V̇E/V̇CO2 in hypoxia (V̇E (H)/V̇CO2 (H)) from P0 to P21. A significant age-by-gender interaction was found at P2, with the male value higher than that of the female. F. V̇E/V̇CO2 in hypoxia versus that in normoxia from P0 to P21. The ratio was lowest at P0 and P13 in both genders. #, P < 0.05; significance in FDR analysis of age-by-gender interactions.

The developmental trends of V̇E/V̇CO2 ratios in normoxia and hypoxia were very similar to those of V̇E/V̇O2 in both genders (Figs. 3D and 3E). A significantly higher value in males than in females was noted in hypoxia at P2 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3E). The ratio also peaked at P5 in males, a day earlier than that in females. When V̇E/V̇CO2 ratios under hypoxia were compared to those in normoxia, the values were above 1 in both genders throughout the 3 weeks except for P0 and P13, when they were close to or slightly below 1 (Fig. 3F). The fall at P13 was significant when data from both genders were combined. No significant gender difference was found at any age.

3.7. Postnatal development of respiratory quotient in normoxia and hypoxia

The developmental trends of respiratory quotient (RQ or V̇CO2/V̇O2) during normoxia and hypoxia were similar between the two genders and were comparable to those published previously (Liu et al., 2009), in which male and female data were combined. No significant gender difference was found at any age tested.

3.8. Postnatal changes in body weight and body temperature with age

The body weight of both male and female rats showed a steady increase with age, comparable to that reported previously (Liu et al., 2006) in which male and female data were combined. In both genders, body weight increased significantly at P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P9, P11, P12, P14, P16, and P21 (P < 0.05 for all). No gender difference was found at any age tested.

The body temperature of both genders increased with age as described previously (Liu et al., 2006). Under hypoxia, the body temperature of both genders was lower than that in normoxia at all ages tested. No significant gender difference was found at any age tested.

4. Discussion

The main findings of the present study are: a) the developmental trends of ventilation and metabolic rates in both normoxia and acute hypoxia during the first three postnatal weeks were very similar between the two genders. Only two significant gender differences were found: i) a higher V̇E/V̇O2 ratio in hypoxia in male than female rats at P1, and ii) a higher V̇E/V̇CO2 ratio in hypoxia in male than female rats at P2. However, even these two differences did not vary far from what might reasonably be expected by chance alone. Thus, gender was never significant as a main effect as analyzed by Mixed Model analysis and False Discovery Rate; and b) with 735 comparisons (35 parameters and 21 age-pairs), the age effect was highly significant in all parameters for both genders. In particular, significant changes during the critical period occurred in the same direction for both genders. Thus, the critical period exists in both genders.

4.1. Gender comparisons outside the critical period

Although both genders had comparable developmental trends in all ventilatory and metabolic parameters tested, at times there was a subtle one-day shift. The reason for such shifts is not known at this time. However, these shifts did not result in any significant gender difference in the absolute V̇E, V̇O2, and V̇CO2 values in normoxia or hypoxia at any age.

4.2. Gender similarities during the critical period

A major finding of the current large-scale, in-depth study was that there was no significant gender difference in all of the ventilatory and metabolic parameters tested during the critical period, both in normoxia and hypoxia. Thus, the critical period of respiratory development exists not only in male rats, but also in female rats. This period was characterized by relatively higher ventilatory and metabolic levels in normoxia but significantly attenuated response to acute hypoxia in both genders. These findings are in agreement with our previous published work (Liu et al., 2006, 2009), in which data from the two genders were combined. The reasons for increased ventilatory and metabolic rates during the critical period are not known, but the acquisition of a thick coat of fur that induces a significant increase in body temperature (Liu et al., 2006), when the regulation of body temperature has not matured (Bertin et al., 1993), can conceivably drive accelerated rates of ventilation, oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production at this time. Other factors, such as hypothalamic influence and general maturational processes may also come into play (Wong-Riley and Liu, 2008). The seemingly “normal” response to hypoxia is deceptive, as increased baseline ventilation necessitates a comparable increase when challenged with hypoxia. A failure to do so constitutes an inadequate response.

A recent report by Holly et al. (2012) agreed with our findings that P12 – P13 falls within a critical period of respiratory development in rats. However, they claimed that it existed only in male and not in female rats. They studied P10-P15 rats plus P30 and P90 rats. Several factors may be considered in comparing the two studies: 1) Holley et al. grouped two days’ data as one, whereas we consider each day separately. This is an important difference, as values at P13 can be significantly different from those at P12, and grouping them together may mask such differences. 2) The number of animals and litters differ significantly between the two studies. The higher N in the present study ensures greater data reliability and statistical power. 3) Holley et al.'s absolute VT values did not exhibit an increase with age, being almost identical between P10 and P90. This is in strong disagreement with published work that indicates a substantial increase in absolute VT from P10 to P90 (Olson, 1994; Joseph et al., 2000; Ohtake et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2004). 4) Both studies used the same rat strain (Sprague-Dawly) from the same vendor (Harlan Laboratory). 5) Our testing verified that there was no adverse effect of exposing rats to only 7 min of hypoxia every 5th day. The adverse effect cited by Holley et al. (Bisgard et al., 2003; Wang & Bisgard, 2005; Bavis et al., 2010) were conducted with at least 4 days of continuous exposure to abnormal gas mixtures. Thus, although Holley et al.'s findings (2012) are enticing, we were not able to confirm their conclusion that the critical period exists only in male rats.

4.3. Implications of gender bias in respiratory disorder

Gender difference in respiratory functions has been of concern due to a gender bias in some human diseases or disorders that may implicate respiratory distress, such as SIDS, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS), in which males exhibit a higher susceptibility than females (Redline et al., 1994; Mage & Donner, 2009). Animal investigations also showed that male animals were more vulnerable to abnormal gas exposure (Zabka et al., 2001a, 2001b; Bavis et al., 2004), but most gender studies concentrate on differences occurring in the adult, when animals are sexually mature and their expressions of sex hormones differ in relative levels and, in the case of females, between periods of the estrus cycle.

To date, what underlies gender bias in sudden infant deaths such as SIDS remains poorly understood. Our current data indicate greater gender similarities than differences in their ventilation and metabolic rates in normoxia and acute, moderate hypoxia during the first three postnatal weeks in rats, at least in the awake state. Other factors not considered in the present study include an effect of sex hormones during sleep (Pickett et al., 1989; Emery et al., 1994), a differential susceptibility to severe serotonergic deficits (Johns et al., 2002; Penatti et al., 2006), and an X-linked protective mechanism against potential terminal cerebral anoxia by catalyzing anaerobic oxidation (Mage & Donner, 2009). More studies are definitely warranted to address these issues.

Highlights.

Hypoxic response was weakest during the critical period in both male and female rats.

Age effect was highly significant in both genders in all parameters and ages tested.

Gender was never significant as a main effect analyzed statistically from P0 to P21.

Both genders exhibited comparable developmental trends in normoxia and hypoxia.

The critical period exists in both genders in rats.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant HD048954. We are grateful to Mr. Dan Eastwood and Dr. Jessica Pruszynski in the Division of Statistics at the Medical College of Wisconsin for their expert consultation and performance of the statistical analyses. Statistical analysis was supported, in part, by grant 1UL1RR031973 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSI) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bavis RW, Olson EB, Jr., Vidruk EH, Fuller DD, Mitchell GS. Developmental plasticity of the hypoxic ventilatory response in rats induced by neonatal hypoxia. J. Physiol. 2004;557:645–660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavis RW, Young KM, Barry KJ, Boller MR, Kim E, Klein PM, Ovrutsky AR, Rampersad DA. Chronic hyperoxia alters the early and late phases of the hypoxic ventilatory response in neonatal rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;109:796–803. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00510.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin R, De Marco F, Mouroux I, Portet R. Postnatal development of nonshivering thermogenesis in rats: effects of rearing temperature. J. Dev. Physiol. 1993;19:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Olson EB, Jr., Wang ZY, Bavis RW, Fuller DD, Mitchell GS. Adult carotid chemoafferent responses to hypoxia after 1, 2, and 4 wk of postnatal hyperoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;95:946–952. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00985.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drorbaugh JE, Fenn WO. A barometric method for measuring ventilation in newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1955;16:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery MJ, Hlastala MP, Matsumoto AM. Depression of hypercapnic ventilatory drive by testosterone in the sleeping infant primate. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994;76:1786–1793. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.4.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano JJ, Kinney HC. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model. Biol. Neonate. 1994;65:194–197. doi: 10.1159/000244052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman AP, McClement J, Himmelstein A, Cournand A. Effects of acute anoxia on the circulation and respiration in patients with chronic pulmonary disease studied during the steady state. J. Clin. Invest. 1952;31:770–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI102662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XP, Liu QS, Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Excitatory-inhibitory imbalance in hypoglossal neurons during the critical period of postnatal development in the rat. J. Physiol. 2011;589:1991–2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley HS, Behan M, Wenninger JM. Age and sex differences in the ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia in awake neonatal, pre-pubertal and young adult rats. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2012;180:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Brown AR, Costy-Bennett S, Luo Z, Fregosi RF. Influence of prenatal nicotine exposure on postnatal development of breathing pattern. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2004;143:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Lubin DA, Lieberman JA, Lauder JM. Developmental effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on 5-HT1A receptors in male and female rat offspring. Dev. Neurosci. 2002;24:522–530. doi: 10.1159/000069363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph V, Soliz J, Pequignot J, Semporé B, Cottet-Emard JM, Dalmaz Y, Favier R, Spielvogel H, Pequignot JM. Gender differentiation of the chemoreflex during growth at high altitude: functional and neurochemical studies. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;278:R806–R816. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal expression of neurotransmitters, receptors, and cytochrome oxidase in the rat pre-Botzinger complex. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002;92:923–934. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00977.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Developmental changes in the expression of GABAA receptor subunits α1, α2, and α3 in the rat pre-Bötzinger complex. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;96:1825–1831. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01264.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal developmental expressions of neurotransmitters and receptors in various brain stem nuclei of rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;98:1442–1457. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01301.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Developmental changes in the expression of GABAA receptor subunits alpha1, alpha2, and alpha3 in brain stem nuclei of rats. Brain Res. 2006;1098:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal changes in the expression of serotonin 2A receptors in various brain stem nuclei of the rat. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:1801–1808. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00057.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal changes in the expressions of serotonin 1A, 1B, and 2A receptors in ten brain stem nuclei of the rat: implication for a sensitive period. Neurosci. 2010a;165:61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal changes in tryptophan hydroxylase and serotonin transporter immunoreactivity in multiple brainstem nuclei of the rat: implications for a sensitive period. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010b;518:1082–1097. doi: 10.1002/cne.22265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal development of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits 2A, 2B, 2C, 2D, and 3B immunoreactivity in brain stem respiratory nuclei of the rat. Neurosci. 2010c;171:637–654. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal development of Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(−) co-transporter 1 and K(+)-Cl(−) co-transporter 2 immunoreactivity in multiple brain stem respiratory nuclei of the rat. Neurosci. 2012;210:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal development of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and tyrosine protein kinase B (TrkB) receptor immunoreactivity in multiple brainstem respiratory-related nuclei of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013;521:109–129. doi: 10.1002/cne.23164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Lowry TF, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal changes in ventilation during normoxia and acute hypoxia in the rat: implication for a sensitive period. J. Physiol. 2006;577:957–970. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Fehring C, Lowry TF, Wong-Riley MTT. Postnatal development of metabolic rate during normoxia and acute hypoxia in rats: implication for a sensitive period. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;106:1212–1222. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90949.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mage DT, Donner M. A unifying theory for SIDS. Int. J. Ped. 2009:368270. doi: 10.1155/2009/368270. 2009, article ID. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake PJ, Simakajornboon N, Fehniger MD, Xue YD, Gozal D. N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor expression in the nucleus tractus solitarii and maturation of hypoxic ventilatory response in the rat. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;162:1140–1147. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9903094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EB., Jr. Physiological dead space increases during initial hours of chronic hypoxemia with or without hypocapnia. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994;77:1526–1531. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.3.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penatti EM, Berniker AV, Kereshi B, Cafaro C, Kelly ML, Niblock MM, Gao HG, Kinney HC, Li A, Nattie EE. Ventilatory response to hypercapnia and hypoxia after extensive lesion of medullary serotonergic neurons in newborn conscious piglets. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006;101:1177–1188. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00376.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett CK, Regensteiner JG, Woodard WD, Hagerman DD, Weil JV, Moore LG. Progestin and estrogen reduce sleep-disordered breathing in postmenopausal women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989;66:1656–1661. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.4.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline S, Kump K, Tishler PV, Browner I, Ferrette V. Gender differences in sleep disordered breathing in a community-based sample. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994;149:722–726. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Bisgard GE. Postnatal growth of the carotid body. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2005;149:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MTT, Liu Q. Neurochemical development of brain stem nuclei involved in the control of respiration. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2005;149:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MTT, Liu Q. Neurochemical and physiological correlates of a critical period of respiratory development in the rat. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2008;164:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabka AG, Behan M, Mitchell GS. Long term facilitation of respiratory motor output decreases with age in male rats. J. Physiol. 2001a;531:509–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0509i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabka AG, Behan M, Mitchell GS. Selected contribution: Time-dependent hypoxic respiratory responses in female rats are influenced by age and by the estrus cycle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001b;91:2831–2838. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]