Abstract

To achieve the benefit of cancer screening, appropriate follow-up of abnormal screening test results must occur. Such follow-up requires traversing the transition between screening detection and diagnosis, including several steps and interfaces in care. This article reviews factors and interventions associated with follow-up of abnormal tests for cervical, breast and colorectal cancers. We synthesized 12 reviews of descriptive and intervention studies published between 1980 and 2008. There was wide variability in definition of follow-up, setting, study population, and reported prevalence rates. Correlates of follow-up included patient characteristics (eg, knowledge and age), social support, provider characteristics, practice (eg, having reminders systems), community and professional norms (eg, quality measures), and policy (eg, federal programs). Effective interventions included patient education and support; delivery systems design changes, such as navigation; and information system changes, most notably patient tracking and physician reminders. Few studies focused explicitly on interfaces and steps of care, such as communication between primary care and specialists, or simultaneously targeted the multilevel factors that affect care. Future practice and research priorities should include development of clear operational definitions of the steps and interfaces related to patients, providers, and organizations; reflect evolving guidelines and new technologies; determine priorities for intervention testing; and improve measures and apply appropriate study designs.

Background

It is well established that regular screening is a major strategy in minimizing cancer morbidity and mortality (1,2). It has been associated with decreased mortality in cervical, colorectal, and breast cancers, as well as decreased incidence in cervical and colorectal cancers through the treatment of cancer precursors (3,4). As a result of this evidence, a variety of interventions to increase regular screening has been tested and promulgated (5–7). Screening rates have generally increased for cervical, colorectal, and breast cancers, but challenges clearly remain because rates of advanced disease at diagnosis persist, particularly in racial minorities and other underserved groups (8–10).

To achieve the maximum benefits of screening, providers and patients must ensure that follow-up of abnormal screening tests occurs. Several studies document that failure to follow-up contributes substantially to advanced cancers (11–13). Evidence-based guidelines recommend steps in care that should be performed for given identified abnormalities (14–18). Some guidelines also specify the timelines for those steps. Problems with delayed detection and treatment result when follow-up of an initial abnormal screening test does not occur or occurs incorrectly or slowly.

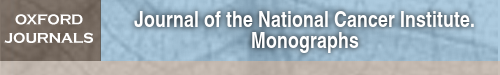

As explicated by Taplin and Rodgers (19), with any type of cancer care, there are multiple specific activities (steps) and multiple interfaces where information and/or responsibility are transferred between the patient and providers, among providers, and across organizational settings. Figure 1 depicts the numerous steps and interfaces in the care process for the follow-up of abnormal screening tests, beginning with reporting of screening test results and continuing through the transition to diagnosis or confirmation of normalcy. As depicted by dotted boxes, follow-up care includes results reporting to, and communication between, physicians and patient, decision making, scheduling, and patient adherence. For example, the results of an abnormal screening fecal occult blood test (FOBT) involve receipt of the result, decision making on further action by the physician, subsequent communication of results by a primary care physician with the patient, and discussion about further steps. Adherence requires the patient to understand subsequent steps and details of appointments and preparation and to address issues of access. The patient's adherence can be enabled by both the primary care and gastroenterology staff via reminders and counseling or by primary care addressing patient apprehensions that exist. Subsequent communication is then needed between the gastroenterologist and the patient and referring provider so that findings are explained and subsequent steps and referral to treatment are accomplished, if needed. To maximize the benefit of early detection, we must understand and influence the complex factors that affect these steps and interfaces in follow-up care.

Figure 1.

Steps and interfaces from screening to diagnosis.

This article reviews current evidence about factors associated with follow-up to abnormal screening tests using an ecological model of care, which considers the role of factors at multiple levels of influence. We then consider intervention strategies, which affect each of the steps and interfaces of follow-up care, and the selection and design of interventions. The objectives of this article were 1) to review the evidence about factors associated with follow-up of abnormal screening tests and interventions that have been shown to improve follow-up and 2) to discuss implications of these findings for future intervention and research.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search for review articles related to follow-up of abnormal screening tests, focusing on tests for colorectal, cervical, and breast cancers. We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINHAL, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for articles published since 1980 in which any field contained references to follow-up of abnormal cancer screening. Search terms included screening, abnormal, follow up OR follow-up, mammo*, FOBT, occult blood, colonoscopy, colorectal neoplasm OR colorectal cancer, pap smear OR vaginal smear. Titles, abstracts, and then as appropriate the full article were reviewed for relevance. Once reviews were identified, we searched for “related articles” in PubMed.

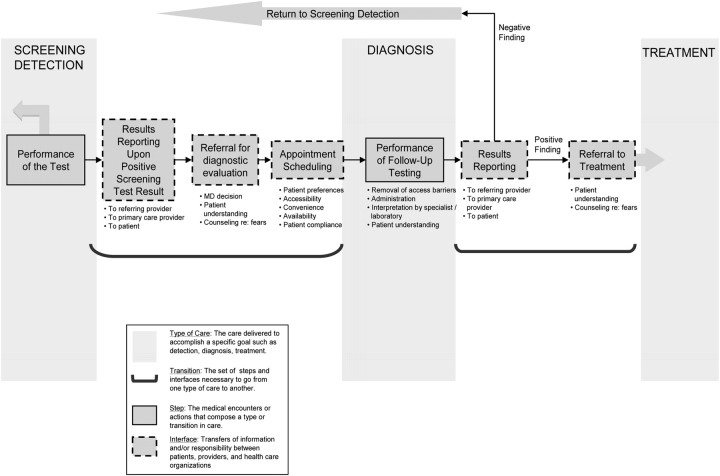

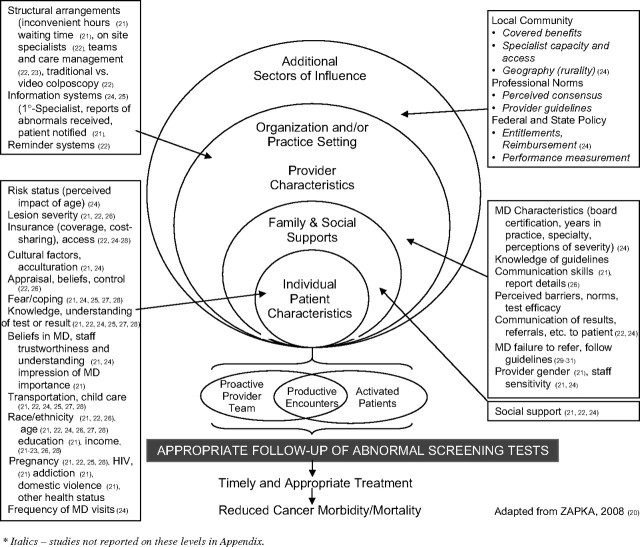

We used an ecological framework (20) to guide the analysis and synthesis of review articles noting the period of review, cancer tests included, criteria for inclusion, design measures, and major findings. As depicted in Figure 2, the model considers hierarchical influences on screening outcomes that vary from federal reimbursement policies to local practice characteristics and to individual physician and patient characteristics. We also synthesized findings from intervention studies and organized strategies according to an expanded Chronic Care Model as depicted in Figure 3 (36,37).

Figure 2.

Levels and factors associated with follow-up to abnormal screening tests.

Figure 3.

Intervention strategies to promote follow-up of abnormal tests.

Findings and Observations

Our search identified 12 reviews of descriptive and intervention studies related to follow-up of abnormal screening tests (21–28,32–35). Ten reported studies concerned Papanicolaou smears, five addressed abnormal mammograms or clinical breast examinations, and three considered follow-up to abnormal FOBTs and/or sigmoidoscopies. Three reviews considered tests for multiple cancers. Since the publication of the reviews, recent studies have considered follow-up issues, which will also be discussed. An annotated summary of the review articles can be found in the Appendix Table 1.

What Factors Are Related to Failure or Success in Completing Diagnostic Follow-Up?

As depicted in Figure 2, descriptive studies have examined factors on several levels associated with follow-up after an abnormal screening test, ranging from the characteristics and social context of individual patients to those of physicians, organizations, and public policies.

Characteristics of Individual Patients.

The preponderance of work has focused on the relationship between individual patient characteristics and adherence to follow-up of abnormal tests. These include sociodemographic factors, knowledge, and beliefs, as well as measures related to health status and access to care. The most consistent factors related to fewer completed follow-ups for all screening tests were lack of insurance, underinsurance, and other measures of socioeconomic status. Race, frequently related to access and insurance, also was a consistent predictor. The studies concerning follow-up for abnormal Papanicolaou tests demonstrated fairly consistent findings that young age, minority race, and low socioeconomic status were risk factors for nonadherence with recommendations for diagnostic testing (21,22,27). Lack of transportation, another access issue, was frequently cited, as well. Although not explicitly discussed in the reviews, one could hypothesize that these access issues were related to performance of follow-up testing (Figure 1).

Issues related to knowledge about and understanding of test results were also commonly cited across cancer types (22,24). Fear and coping style also were related in several studies. These factors are likely related to the understanding of the referral evaluation process so that the steps in scheduling and tests performance are completed. The relationship of health status issues such as pregnancy, HIV status, addictions, and domestic violence could be related to several interfaces because of fears, lack of information, conflicting priorities, among other reasons.

Consideration of how such individual factors are related to the steps of the follow-up process would help select priority objectives and guide intervention and message choice.

Family and Social Supports.

Interestingly, issues of cultural context, social support (instrumental and emotional), and related social network factors have been found to be related to enhancing, as well as reducing, Papanicolaou and mammography test follow-up adherence by African American and Hispanic women (21,24,25). Whether cultural factors are an individual characteristic or a factor that influences behavior through family, social, and community supports is not clearly articulated in the published work, and relatively little has been done in this area with respect to reporting relevant measures. Inconsistent evidence may reflect differences in measures or may reflect personal preferences as they affect the appointment scheduling decision.

Provider Characteristics.

Studies of all three screening types have explored selected physician factors and their relationship to follow-up for abnormal results. Of special note are the factors of communication and decision making. The importance of communication between patient and physician about risk, test choice, results, and necessary follow-up was frequently noted (39). Wolf et al. (40) illustrated the complexity of communication tasks (eg, describe procedure and describe advance preparation, benefits, and risks) and demonstrated that physician self-report of completion of these tasks was significantly higher than those observed in a separate video sample. Yet few studies have actually assessed the completion of communication regarding the discrete steps necessary for follow-up. This complexity of communication not only with the patient but also between providers at other locations reinforces the importance of attention to steps that would enhance successful transition between screening and diagnosis highlighted in Figure 1.

Physician decision making and failure to refer for further testing contribute to failure to follow-up (29,41,42). This may be because of not knowing of an abnormal test result or the physician's decision not to refer. Turner et al. (30) reported that primary care physicians, compared with specialists, felt that they “knew” and because of that were less likely to order follow-up for complete diagnostic evaluation after an abnormal FOBT. Primary care physician action was additionally influenced by their beliefs about the value of complete diagnostic evaluation. Nadel et al. (31) also outlined physician's lack of adherence to guidelines concerning follow-up, which also has been noted in diagnostic follow-up after FOBT screening in the elderly (43). Additionally, some physicians reported not notifying women because they did not think that follow-up would be completed, that is, they assumed nonadherence in the patient's part (21).

Characteristics of Organizations and Practices.

Prompted perhaps by research and quality improvement initiatives, the typology of interventions of the Chronic Care Model (36) has emphasized the importance of practice-level structures and processes to performance outcomes. Felix et al. (44) recommend that interventions need to focus on provider and system features rather than on clients. Despite these studies, the mechanism of influence and the path to organizational adoption and maintenance are not clear.

Reminder systems for providers, as well as reminder systems for patients (mail and phone), have been frequently and consistently cited as significantly beneficial (29,41), as have other information tracking systems (24,25). Challenges remain in understanding the details of the reporting process, however. For example, women report never having heard about an abnormal Papanicolaou test (21), which reflects a failure in communication during the steps from screening to diagnosis, but exactly where needs further study.

In a few studies, organizational structural characteristics, such as waiting times (21) and on-site specialists and technology options (22) have demonstrated a relationship to completed follow-up. These predictably improve access and convenience so the performance of follow-up testing occurs. Several studies discuss the growing interest in the relationship of case managers or navigators to adherence, including the impact on the prevalence follow-up of abnormal tests (23). Navigators may essentially tailor intervention strategies to eliminate failures in several steps of the care process.

Local Community and Professional Norms and Public Policy Initiatives.

The reviews and other commentaries in the professional literature have noted the important relationship of local professional norms as well as geographic variation in norms, supply and access, and public policy initiatives to preventive services delivery and uptake. In fact, Barr et al. (38) emphasize that concepts of public health must be integrated with the Chronic Care Model. Variation in screening prevalence by residence location has been noted, and this area of inquiry has been increasing with the evolution of geocoding technology (45,46). Little is known, however, about how follow-up care differs across regions.

Federal initiatives have the potential to improve follow-up care. A notable example is the effort of federal agencies in encouraging the navigation research agenda. These include the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which funded six demonstration sites for pilot screening programs targeting minority beneficiaries in 2006, and the National Cancer Institute's Effort to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, which funded the Patient Navigation Research Program (PNRP) in 2007 (33). Successful advocacy to include follow-up tests as part of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) is a prime example of federal and state public policy to ensure access to care for underserved women, first by subsidizing screening and later for diagnostic services (47). To achieve population-wide improvements in adherence to prevention services, public policy is of key importance (48). Given the importance of insurance, as well as details of benefit structure within insurance policies (49), state policies have also mandated insurers to cover such selected screening and diagnostic tests (50). These public policies have impact on follow-up as they enable access to and receipt of testing.

Professional norms have been influenced by the promulgation of evidence-based guidelines for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers screening (51), some of which include evidence-based guidelines for follow-up diagnosis (16,17,30,52). Quality expectations and benchmarks, such as the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), have been shown to influence health plan and provider performance in screening (53). However, no HEDIS measures related to prevalence of abnormal test follow-up have been developed.

What Is Known About Interventions to Improve Follow-Up of Abnormal Tests?

As introduced earlier, the Chronic Care Model (36) represents a widely used typology of intervention strategies to improve care outcomes. This typology complements the levels within the ecological model (Figure 2) used to outline factors affecting follow-up reported in descriptive studies. Figure 3 represents a summary look at the reported effectiveness of intervention strategies to improve follow-up of abnormal screening tests for the three cancers. We note the potential mechanism through which the intervention affected or could affect the steps and interfaces within the care process.

Studies of patient self-management and decision support include patient education via various modalities (eg, workshops and reminders), informational materials, and telephone and in-person counseling. Although few studies report a guiding theoretical model or framework (22,24), these interventions were usually designed to address several of the individual patient-level characteristics illustrated in Figure 2, including knowledge deficits, fears, forgetfulness, or other patient predisposing factors. Additional intervention strategies that were consistently reported as successful, particularly for women needing follow-up to abnormal Papanicolaou tests, included transportation assistance and case management (21,22,25,28,32,35). Such strategies enable and reinforce the performance of the follow-up testing step by eliminating selected barriers and implementing systems and/or staff to facilitate successful completion of the steps in the process of care.

Delivery system design strategies have been shown to directly affect performance of follow-up testing and include the implementation of same-day testing and same-site testing, because these strategies eliminate the interface with other organizations, repeat visits and the process of appointment scheduling (35). A growing literature highlights the effectiveness of patient case managers, more recently referred to as “navigators” (33,54,55). Within the broad categorization of “navigation,” programs vary by intensity of management and services coordinated. Case management interventions may reflect “a minimal coordination” model involving services coordination, advocacy and reassessment, or “sociomedical services” model, extending to issues related to housing, work, or food (23). Variability in impact on care across studies may well reflect the intensity and comprehensiveness of the support and assistance, as well as the context of the practice and community environment resources. Although criticized for not being tested by randomized trials, uncontrolled evaluations suggest that they overcome the challenges of interfaces and steps in care by providing assistance tailored to an individual patients’ navigation between the many offices, organizations, and providers involved in care (23).

There is little explicit study of the impact of clinical decision support strategies on follow-up completion; however, the mechanism of action may be the same as it is for improving screening performance as reviewed by Anhang Price et al. (56).

With respect to strategies which improve clinical information systems, studies of interventions to improve clinician cueing/reminders have clearly confirmed significant and consistent effectiveness for all cancer screening test follow-up (24). These did, however, vary by mode (eg, electronic, paper record, and telephone). Such systems could cue the physician about the nonreceipt of a recommended screening test, the receipt of an abnormal test, and/or serve as a cue to referral for diagnostic evaluation.

In summary, evidence suggests that multiple intervention strategies can improve follow-up, although the mechanism(s) of action are not clear. Another challenge, rarely discussed, is the maintenance and institutionalization of the interventions once a funded research study ends (57). Better understanding of the multiple mechanisms of coordinating multiple steps in care and the associated interfaces among providers would inform planning decisions.

Discussion

We organized published evidence related to receipt of follow-up care for abnormal screening tests using an ecological framework and the chronic care typology of interventions. Our review highlights several issues and recommendations for research and practice related to the mechanisms actually operating to affect the steps and interfaces in care, which we discuss below.

Develop a Clear Operational Definition of “Follow-up” Including Explication of the Levels of Influence and the Steps and Interfaces Within the Follow-Up Care Process

Virtually every review emphasized the variability across studies in the operational definition of “follow-up.” This included the dimensions of 1) eligibility for follow-up, 2) definition of the appropriate set of diagnostic tests, and 3) the appropriate window of time for follow-up testing (34). We further suggest that it is important to differentiate the steps and interfaces in the transition from screening to diagnosis, which highlights the level and mechanism of the intervention. Such clarity would contribute significantly to comparing and generalizing across studies.

Figure 2 depicts the levels of influence on provider–patient encounters but does not fully reflect the complexity of the underlying mechanisms. Although many studies consider “systems” and “levels” of influence in describing relationships and intervention effects, terms need specific definition. For example, the term “systems” has been used with respect to the individual practice level (“practice systems”), larger organizations (eg, community health center with multiple practice sites), or the overall health-care system (eg, insurers and specialists) (58). Another example from Figure 3 is the term “leadership,” which may mean organization or practice leaders or formal and informal champions of care (58). Levels of influence in Figure 2 reflect a nested set of factors where each larger part of the figure may influence or be influenced by everything below it, but in fact, the direction and strength of the relationship between the levels is rarely closely examined.

The transitions, interfaces, and steps of care described by Taplin and Rodgers (19) and others (59,60) are rarely described explicitly or explored in studies of follow-up care. In a recent study, Singh et al. (61) did find that one of the most common process breakdowns in missed opportunities to detect colorectal cancer was related to follow-up of abnormal tests. Abercrombie (21) did note that some researchers reported differences in adherence to follow-up of Papanicolaou smears at certain points in the process of care. As introduced earlier, contributing factors to a physician's lack of referral for diagnostic testing include lack of notification, beliefs about the merits of diagnostic evaluation (20,63), or assumptions about patient noncompliance (21). These examples of delineating steps and interfaces of care provide rich examples of how important it is to understand failures in the process to undertake the intervention with most promise of impact.

Additionally, specific patient characteristics may require specific attention in the follow-up process, including emotional support and assurance of confidentiality when referred, as in the case of adolescents referred for a colposcopy (21). However, even if reporting to physicians and patients were perfect, the transition from screening to diagnosis often involves scheduling a subsequent diagnostic appointment with a subspecialty provider for a colposcopy, colonoscopy, or other diagnostic test (28).

Again, our review of reviews did not differentiate clearly this step in process of care or evaluate factors affecting it. Thus, we and others recommend a more explicit exploration of the steps and interfaces in the transition from screening to diagnosis (28). The engineering and manufacturing literature is replete with examples of evaluations that break down a process and address the component parts (63). The choice and design of interventions will depend on which step/interface is broken and which factors influence that step/interface.

Practice and Research Initiatives Must Reflect Potential Impact of Evolving Guidelines and New Screening Technologies When Interpreting Previous Evidence and Experience

A challenge to this work is that clinical guidelines for screening and follow-up have evolved and will continue to do so. This in turn affects the complexity and variation in the steps and interfaces for the various tests for each type of cancer (cervical, breast, and colorectal). An illustration of the potential complexity is the guideline for use of human papillomavirus DNA testing that varies according to five cytopathology categories (15). This level of complexity has been noted to require a high level of vigilance by providers, and for researchers it creates an array of “appropriate” follow-up steps that defies simple evaluation (21). Added to that complexity is the fact that technology innovation continues to evolve, which in turn may change the interfaces with specialists and organizations. These evolving guidelines and continuing introduction of new technologies suggest that understanding and documentation of the steps and interfaces in process of successful follow-up care is all the more important.

Determine Priorities for Intervention Testing

The categories of strategies suggested by the expanded Chronic Care Model provide a useful filing cabinet of potential broad options for interventions. Studies need to drill down to the relative impact of factors in each level in the ecological model to determine whether a combination of intervention strategies across levels aimed at multiple targets (eg, systems, practices, providers, and patients) could have more consistent impact and/or potential for implementation than interventions directed at one level. An example of “drilling down” to find process deficiencies was noted in a recent study by Singh et al. (61) when they found that even when health-care providers received and read abnormal results in an integrated medical record system, timely follow-up did not always occur. Studies that explicate the factors related to steps and interfaces should be a priority, given the inconsistency of impact and adoption of interventions across screening types, organizations and patients aimed at one level (64). The inclusion of cost-effectiveness methods in studies also is needed to inform adoption and diffusion of effective strategies.

As noted in a number of articles in this supplement (65), communication between the primary care physician and relevant subspecialist (eg, cytopathologist, gastroenterologist, and radiologist) is also critical to follow-up, and interventions to improve this dynamic should be tested. Communication from specialist to ordering physician about an abnormal finding is typically the first step in the process of either a cancer diagnosis or identifying the patient as not having cancer. Some specialists may additionally report directly to the patient, notably mammographers and gastroenterologists (66,67).

Getting the results to the right person is key in the follow-up process, but that person must interpret them correctly and make the appropriate referral decision and that referral must be acted upon by the patient. The interpretation is subject to professional education, but the successful referral also reflects communication among staff, between providers, and between offices where care is delivered: the physician and organizational interfaces of care. This referral process therefore needs to be viewed in a larger systems framework that considers the roles of the providers, their staff, and their patients. For example, nurses and physicians’ assistants have an important role in communication (21), so stepping back from physician/patient communication to examine the role of teamwork and office organization may yield more insights and progress. Another example is the recent reports of quality improvement activities in the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) and community health centers. Singh et al. (13) found that one breakdown was failure in the gastroenterology service to reschedule colonoscopies after an initial consultation. Taplin et al. (68) noted that quality improvement activities concentrating on documentation via clinical tracking capabilities improved steps in the process of care including timely notification of result and percent abnormal tests evaluated within 90 days.

Given the complexity of recommendations from evidence-based guidelines, as well as variability in needs of population subgroups, another intervention priority is provider–patient communication (39). It is certainly true that patients need an understanding of their cancer risk and the importance of testing and follow-up. For example, recent work has investigated the influence of written endoscopy reports on anxiety and adherence (69). Providers need to attend to potential fears and other barriers to follow-up. Additionally, the ease with which the patient schedules an appointment and is assisted through the logistics of contacting, securing, and completing the diagnostic work-up also needs examination. The growing emphasis on patient-centered counseling and shared decision making represents yet another dimension of communication related to abnormal test follow-up (70).

Although systems issues and the complexity of their influences are important, the populations studied also have important differences. In their review, Yabroff et al. (24) noted that comparisons of studies were limited because racial or socioeconomic composition was not reported in half of the studies. Abercrombie (21) emphasizes differences between cultures in both related factors and differential response to interventions. Although many studies have highlighted the need to focus on improving follow-up among underserved populations (22,23,33), the priority for research should focus on intervention studies rather than on descriptive studies.

As Masi et al. (23) and Wells et al. (33) report, studies of case manager or navigation interventions have showed very promising data. Because the complexities of navigation interventions pose difficulties for randomized designs, a study to quantify the relative benefits of the levels of case management (minimal, coordination, sociomedical) should be a priority. An additional research challenge is to articulate the elements of navigation which are most cost-efficacious.

The reviews we examined repeatedly highlight the complexity introduced into understanding and generalizing of study findings by the variety of settings and populations examined. This is inevitable, given the realities of the US health-care system, but it makes generalization difficult. While some intervention strategies, such as telephone reminders to patients, clinic tracking systems, and provider reminders, have fairly consistent impact on ultimate adherence, the size of that affect varies considerably with the population and setting. “One size does not fit all,” and we need better evidence concerning optimal combinations of intervention strategies for specific populations and settings.

Improve Measures and Apply Appropriate Study Designs

Inherent in an effort to improve follow-up and build an evidence base is the issue of measurement (24). Measures of timeliness and appropriateness must be established through efficacy studies and consensus guidelines. These guidelines will then provide direction for choice of outcome measures in intervention studies. Several reviews noted the presence, or more often the absence, of guiding models to the selection of independent measures (22–24). As we consider more theory-guided studies that include measures from several levels, interfaces, and steps, attention must be paid to grounding the selection of measures (24) and content and construct validity (71) in political, organizational, and behavioral theory. Availability of data sources for complex measures also will be a challenge (72).

These measures must also be relevant to the multilevel research designs required to separate out effects. Application of innovative and appropriate study designs and analytic techniques for multilevel interventions require careful consideration. The unit of randomization and the unit of analyses and resultant statistical power considerations will challenge the balance of methods needed to maximize internal validity as well as the time and cost burden of the research design and measurement methods [see Murray et al. (73)].

Conclusions

This review highlights the strengths, limitations, and major themes in follow-up after abnormal cancer screening tests. Several decades of work demonstrate that many factors at multiple levels of the health-care environment affect adherence to follow-up procedures, but the complexity of follow-up makes simple generalizations impossible. The variability of impact underscores the need for better consensus on operational definitions of follow-up outcomes, including explication of the steps and interfaces in the process of care during transition from screening to diagnosis and treatment. The preponderance of evidence suggests that follow-up levels differ across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. Changing this differential will require a greater understanding of how multiple factors influence the steps which constitute the transition from screening to diagnosis, as well as the diagnostic process itself (23).

We acknowledge several limitations in this review and summary. Just as reported prevalence of appropriate follow-up varied across studies, so did the rate of improvement in adherence attributed to various intervention strategies. For example, in one review, improvement in Papanicolaou test follow-up after intervention ranged from 18% to 30%, but the populations and the settings varied (21). Thus, attribution of effectiveness must be cautious. More research and more reviews have considered adherence with respect to Papanicolaou test than for other cancers. The reviews frequently repeated reports of the same articles (note period of reviews). This may create an impression of stronger evidence than actually exists. Additionally, some relevant work has probably been inadvertently omitted, and some recent published evidence may have been omitted. Several issues related to follow-up of abnormal tests are important but beyond the scope of this review. These include concern about the rate of false-positive or false-negative interpretations (18) and the impact of such problems on periodic screening (74,75).

The evidence review demonstrates that multiple intervention strategies can improve follow-up. It also highlights the need for further research related to the effectiveness of follow-up interventions targeted at 1) multiple levels of influence; 2) problems in the steps and interfaces of the diagnostic process, which may vary among cancer screening protocols; and 3) problems in follow-up among underserved populations, given their disproportionate burden. This review and summary, however, highlights important directions for future research to improve the follow-up of abnormal screening tests and points out that a great deal can be gained if we consistently separate process issues during the transition from screening or during diagnostic follow-up.

Funding

This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract no. 12610–86626.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Review of reviews related to follow-up of abnormal screening tests for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers*

| Reference | CaTest; Period | Criteria; No. of studies | Findings | Notes |

| Abercrombie (21) | Papanicolaou test; 1985–1999 | Descriptive and intervention studies; English; N = 25 (intervention studies = 9) | Prevalence: 15%–42% of women with abnormal Papanicolaou tests do not follow-up or are nonadherent | Investigators commented on role of nurses in facilitating adherence |

| Descriptive: characteristics of the woman (ie, demographics, social support, lack of understanding, and fear, interpretation of severity) and providers and health-care system (ie, lack of notification, inconvenient clinic hours, male providers, and insensitive staff) was associated with follow-up, although some inconsistency between studies | Recommendations: future studies should consider the multifactorial nature of adherence and obtain more information about women at highest risk for nonadherence | |||

| Interventions: strategies successful in improving follow-up by 18%–30% included telephone reminders and counseling, educational programs, and economic incentives | ||||

| Bastani et al. (34) | FOBT; Papanicolaou smear; Sigmoidoscopy; Mammography; Period not stated | Descriptive and intervention studies. Referred primarily to RCTs or quasi-experimental designs; N = not explicit | Descriptive: substantial variability exists across studies regarding patient eligibility (eg, severity of abnormal finding) and definitions of appropriate and timely follow-up. Negative psychological states were associated with abnormal results, but little is known about effects on follow-up. Most studied patient factors; fewer address provider, practice, and policy levels | Investigators framed review as “lessons learned.” Conceptual model identified four levels: policy, practice, provider, and patient |

| Interventions: effective patient-level interventions include mail and telephone reminders, telephone counseling, and print educational interventions. Most focused on abnormal Papanicolaou smears; less is known about patients with abnormal breast screens and little about colorectal cancer screening tests. Practice-level barriers are potentially modifiable, but few interventions tested | Recommendations: standardization of populations and definitions of follow-up and studies of validity of various methods of obtaining data needed. Studies should evaluate psychological sequelae of abnormal and receipt of care | |||

| Evaluation of provider, practice, and policy (federal, state, and local) level factors and interventions, and consideration of interdependence of measures across levels recommended | ||||

| Eggleston et al. (22) | Papanicolaou smear; 1990–2005 | Research addressing adherence, prevalence, risk. Descriptive and intervention studies conducted in the United States; N = 14 descriptive; N = 12 experimental intervention studies | Prevalence: wide ranges of follow-up adherence, 19%–86% | Recommendations: interventions should be adapted and applied across racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups to reach high-risk women |

| Descriptive: minority race/ethnicity, urban setting, lesion severity, health beliefs, knowledge of findings, and social support associated with adherence; inconsistent evidence for age, education, income, insurance, pregnancy, and smoking status | ||||

| Interventions: communication interventions, including telephone reminders, counseling, and education, increased follow-up compliance as did interventions to improve access (transportation, child care, and voucher) and case management approaches | Interventions that focus on the interplay among psychological, educational, and communication barriers are necessary | |||

| Khanna and Phillips (27) | Papanicolaou smear; 1968–1999 | Descriptive and intervention studies (primarily RCTs) in English. Conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada; N, not provided for descriptive studies; N = 12 intervention studies | Prevalence: 10% to >40% nonadherence. Definition of nonadherence was not standard | Recommendations: investigators stressed the need to consider the interplay of emotional, logistic, cultural, and socioeconomic factors related to adherence |

| Descriptive: factors associated with nonadherence include younger age, minority ethnicity, lower education, and lower-grade abnormalities. Barriers to follow-up were lack of understanding of colposcopy, fear of cancer, forgetting appointments, and lack of time, money, or childcare. Adverse emotional consequences of abnormal tests and impact on follow-up were noted | ||||

| Interventions: most effective strategies were personalized reminders to patients by their primary physicians and case management dictated by the size, structure, and style of the practice | ||||

| Lester and Wilson (28) | Colposcopy referral default; 1986–September 1997 | Descriptive and intervention studies conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, Canada, and Scotland; N = 13 descriptive; N = 4 intervention | Prevalence: default (nonadherent with referral) rates ranged from 3% to 12%. Vast majority of women referred to colposcopy eventually attended | Recommendations: if future research supports default as a problem, greater cooperation across the primary or secondary care interface and use of extended primary care team may be cost-effective means of increasing compliance |

| Descriptive: factors associated with default included age, social class, insurance, lack of understanding, forgetfulness, child care, and pregnancy. Association between anxiety and colposcopy default unclear | ||||

| Interventions: strategies that include transportation incentives and telephone counseling effective in improving attendance | ||||

| Marcus and Crane (32) | Papanicolaou smear; Period not specified | Descriptive and intervention studies including randomized, quasi-experimental and observational studies conducted in the United States | Prevalence: loss to follow-up up to 80%, with typical range of 30%–50% | Recommendations: because response to interventions varied by socioeconomic status, race, and insurance, targeting (and sequencing) specific interventions to patients will be useful |

| Interventions: effective strategies included telephone follow-up and reminders, mailed motivational brochures, audiovisual programs, clinic-based educational presentation and workshops, transportation incentives (bus tokens, parking permits) vouchers, and nurse coordinators, as well as multicomponent strategies. Most interventions not conducted in public health departments | ||||

| Investigators caution that efficacy trials are conducted in settings that may not generalize to real world | ||||

| Masi et al. (23) | Mammogram or clinical breast examination; 1986–2005 | Intervention studies with randomized or quasi-experimental design conducted in the United States. Health-care organization based with >50% minority population; N = 5 | Interventions: outcomes assessed included time to follow-up appointments and time to biopsy. All five studies targeted the patient. Studies used different models of case management (minimal, coordination, sociomedical); some with activities studied separately elsewhere, including referral assistance, telephone reminders, assistance with logistics, and computerized tracking. All effective in expediting diagnostic follow-up | Conceptual model includes patient and provider targets and cancer continuum of screening, diagnosis and treatment |

| Investigators scored studies on reporting features, external validity, bias, and confounding | ||||

| Recommendations: evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of case management models a priority | ||||

| McKee (25) | Papanicolaou smear; February 1966–February 1996 | Descriptive and intervention studies; N, not provided | Prevalence: adherence ranging from 20% to 74% depending on setting | Recommendations: patient-centered and office-based tracking intervention strategies based on study findings were recommended |

| Descriptive: nonadherence associated with minority race/ethnicity, low SES, age, insurance, access barriers (transportation, cost, childcare), as well as knowledge about findings and fears | ||||

| Interventions: effective strategies included telephone counseling, educational pamphlets, transportation incentives, office-based reminders to physicians and patients | ||||

| Yabroff et al. (35) | Papanicolaou smear; 1980–May 1999 | Intervention studies with RCT or concurrently controlled trial with a prospectively followed control group, conducted in and outside the United States; N = 10 | Interventions: cognitive interventions using interactive telephone counseling were most effective, increasing follow-up by 24%–31%. Behavioral interventions (eg, patient reminders) were also effective, increasing follow-up by up to 18%. The single sociological intervention used videotaped peer discussions and was not associated with increased follow-up. The effectiveness of interventions using multiple strategies was inconsistent. The definition of abnormal Papanicolaou tests, patient characteristics, settings, and outcomes measured varied across studies | Interventions classified as cognitive, behavioral, or sociological |

| Recommendations: adaptation of effective strategies to improve follow-up for abnormal mammograms and colorectal cancer screening is a priority. Development of physician- and system-targeted interventions, and evaluation of the cost-effectiveness, are important priorities for future research | ||||

| Yabroff et al. (24) | Mammography or CBE; Papanicolaou smear; FOBT or sigmoidoscopy; December 1980–December 2001 | Descriptive and intervention studies conducted in the United States. RCT and nonexperimental designs are reported; N = 45 observational (15 mammography, 21 Papanicolaou, 11 FOBT); N = 23 intervention studies (three mammogram or CBE, 17 Papanicolaou, 2 FOBT/sigmoidoscopy, two multiple screens) | Prevalence varied widely: 33% of studies reported ≤75%, 46% of studies reported rates of 50%–74%, and 19% of studies reported <50% prevalence of completed follow-up | Conceptual model included patient, provider, and health-care system measures |

| Descriptive factors at provider level (communication between providers and to patients, provider background/experiences, cognitive representation and perceived norms); patient (demographics, insurance, lack of knowledge and understanding of results, psychological reactions/adaptation, severity, concerns about femininity or age, concern about general health); and health-care system levels (scheduling, care availability, tracking and reporting system, coordination of care) associated with follow-up. Study population, definition of abnormal tests and appropriate follow-up, and their measurement vary widely across studies | Few intervention studies have investigated long-term continuation of improvement nor focused on provider–provider and patient–provider communication | |||

| Interventions: effective provider-targeted (reminders, feedback reports, and education), patient-targeted (education, peer counselors, reminders, and vouchers), and system-targeted (case managers, tracking systems, on-site specialty, and same-day testing) strategies improved follow-up | Recommendations: increasing availability of screening follow-up data, use of theoretical models, and cost-effectiveness of interventions important priorities for future research | |||

| Wells et al. (33) | Breast; Cervical; Prostate; CRC test; Through October 2007 | Intervention studies of patient conducted in the United States and Canada; N = 5 studies related to improving adherence with recommended follow-up tests | Interventions: patient navigation increased adherence to follow-up care and timeliness of follow-up and reduced anxiety compared with nonparticipants in RCT, prospective, and retrospective cohort, and pre-post studies (improvements ranged from 21% to 29%). Most studies had methodological limitations, such as a lack of concurrent control groups, small sample sizes, and contamination with other interventions | Recommendations: scientifically rigorous evaluation of patient navigation using standard definitions of navigation, including training, tasks, target populations, and outcomes important priorities |

| Wujcik and Fair (26) | Mammography; 1995–2006 | Descriptive studies conducted in the United States or Canada; N = 22 (13 assessed women with abnormal screen; nine assessed women with a diagnosis of breast cancer after screening mammography) | Prevalence: definition of “delay” ranged from 28 d to 9 mo, most common within 3 mo. 68% delayed in completing testing by >60 d; 31.9%, >90 d; 50%, >4 mo; and 34%, >1 y | Recommendations: further exploration of provider and system barriers recommended, including documentation of communication about follow-up. Development of interventions that address patient, system, and provider barriers is needed |

| Descriptive: patient factors associated with delay were non-white race and being uninsured. Inconsistent findings for age, family history, health beliefs, and severity of mammography or lump. Provider communication, including specific follow-up recommendations and documented discussions, was associated with less delay. Systems barriers included lack of surgical access or timely appointments |

CA = cancer; CBE = clinical breast exam; CRC = colorectal cancer; FOBT = Fecal occult blood test; RCTs = randomized clinical trials; SES = socioeconomic status

Footnotes

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial products , or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of an anonymous reviewer.

References

- 1.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2008: a review of current American cancer society guidelines and cancer screening issues. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):161–179. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2008. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; AHRQ Publication 08-05122. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm. Accessed May 16, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson FB, Barro JL, Atkin W, et al. Review article: population screening for colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(11–12):1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Meara AT. Present standards for cervical cancer screening. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14(5):505–511. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron RC, Rimer BK, Breslow RA, et al. Client-directed interventions to increase community demand for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1) suppl:S34–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron RC, Rimer BK, Coates RJ, et al. Client-directed interventions to increase community access to breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1) suppl:S56–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabatino SA, Habarta N, Baron RC, et al. Interventions to increase recommendation and delivery of screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by healthcare providers: systematic reviews of provider assessment and feedback and provider incentives. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1) suppl:S67–S74. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA. Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with health care access among United States women, 2002. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(2):260–275. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(6):923–930. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leyden WA, Manos MM, Geiger AM, et al. Cervical cancer in women with comprehensive health care access: attributable factors in the screening process. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(9):675–683. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taplin SH, Barlow WE, Ulcickas-Yood M, et al. Re: breast cancer screening comes full circle. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(6):461. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh H, Daci K, Petersen LA, et al. Missed opportunities to initiate endoscopic evaluation for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(10):2543–2554. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright TC, Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright TC, Jr, Schiffman M, Solomon D, et al. Interim guidance for the use of human papillomavirus DNA testing as an adjunct to cervical cytology for screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):304–309. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000109426.82624.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerlikowske K, Smith-Bindman R, Ljung BM, Grady D. Evaluation of abnormal mammography results and palpable breast abnormalities. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(4):274–284. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molins E, Macia F, Ferrer F, Maristany MT, Castells X. Association between radiologists’ experience and accuracy in interpreting screening mammograms. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-91. April 25;8:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taplin SH, Rodgers AB. Toward improving the quality of cancer care: addressing the interfaces of primary and oncology-related subspecialty care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;(40):3–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zapka JG. Innovative provider- and health system-directed approaches to improving colorectal cancer screening delivery. Med Care. 2008;46(9) suppl 1:S62–S67. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abercrombie PD. Improving adherence to abnormal Pap smear follow-up. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30(1):80–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eggleston KS, Coker AL, Das IP, Cordray ST, Luchok KJ. Understanding barriers for adherence to follow-up care for abnormal pap tests. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(3):311–330. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masi CM, Blackman DJ, Peek ME. Interventions to enhance breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment among racial and ethnic minority women. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5) suppl:195S–242S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yabroff KR, Washington KS, Leader A, Neilson E, Mandelblatt J. Is the promise of cancer-screening programs being compromised? Quality of follow-up care after abnormal screening results. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(3):294–331. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKee D. Improving the follow-up of patients with abnormal Papanicolaou smear results. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6(6):574–577. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.6.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wujcik D, Fair AM. Barriers to diagnostic resolution after abnormal mammography: a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(5):E16–E30. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305764.96732.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khanna N, Phillips MD. Adherence to care plan in women with abnormal papanicolaou smears: a review of barriers and interventions. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(2):123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lester H, Wilson S. Is default from colposcopy a problem, and if so what can we do? A systematic review of the literature. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(440):223–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher DA, Jeffreys A, Coffman CJ, Fasanella K. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1232–1235. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner B, Myers RE, Hyslop T, et al. Physician and patient factors associated with ordering a colon evaluation after a positive fecal occult blood test. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(5):357–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadel MR, Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, et al. A national survey of primary care physicians’ methods for screening for fecal occult blood. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(2):86–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus AC, Crane LA. A review of cervical cancer screening intervention research: implications for public health programs and future research. Prev Med. 1998;27(1):13–31. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bastani R, Yabroff KR, Myers RE, Glenn B. Interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal findings in cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101(5) suppl:1188–1200. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yabroff KR, Kerner JF, Mandelblatt JS. Effectiveness of interventions to improve follow-up after abnormal cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 2000;31(4):429–439. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glasgow R, Orleans C, Wagner E, Curry S, Solberg LI. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):579–612. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zapka JG, Lemon SC. Interventions for patients, providers, and health care organizations. Cancer. 2004;101(5) suppl:1165–1187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, et al. The expanded Chronic Care Model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hosp Q. 2003;7(1):73–82. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2003.16763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schofield PE, Butow PN. Towards better communication in cancer care: a framework for developing evidence-based interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Physician-patient communication about colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0289-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baig N, Myers RE, Turner BJ, et al. Physician-reported reasons for limited follow-up of patients with a positive fecal occult blood test screening result. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(9):2078–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jimbo M, Myers RE, Meyer B, et al. Reasons patients with a positive fecal occult blood test result do not undergo complete diagnostic evaluation. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):11–16. doi: 10.1370/afm.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lurie J, Welch H. Diagnostic testing following fecal occult blood screening in the elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(19):1641–1646. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.19.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felix HC, Bronstein J, Bursac Z, Stewart MK, Foushee HR, Klapow J. Family planning provider referral, facilitation behavior, and patient follow-up for abnormal Pap smears. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(5):733–744. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dailey AB, Kasl SV, Holford TR, Calvocoressi L, Jones BA. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic predictors of nonadherence to mammography screening guidelines. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(11):2293–2303. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lian M, Schootman M, Yun S. Geographic variation and effect of area-level poverty rate on colorectal cancer screening. BMC Public Health. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-358. Oct 16;8:358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eheman CR, Benard VB, Blackman D, et al. Breast cancer screening among low-income or uninsured women: results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, July 1995 to March 2002 (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(1):29–38. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-4558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colditz GA, Samplin-Salgado M, Ryan CT, et al. Harvard report on cancer prevention, volume 5: fulfilling the potential for cancer prevention: policy approaches. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(3):199–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1015040702565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman C, Ahmed F, Franks A, et al. Association between health insurance coverage of office visit and cancer screening among women. Med Care. 2002;40(11):1060–1067. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.State Cancer Legislative Database Program. National Cancer Institute. http://www.scld-nci.net/index.cfml. Accessed May 16, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299(2):211–213. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarfaty M, Myers RE. The effect of HEDIS measurement of colorectal cancer screening on insurance plans in Pennsylvania. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(5):277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmieri FM, DePeri ER, Mincey BA, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic program for medically underserved women with abnormal breast screening evaluations in an urban population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(4):317–322. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60539-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anhang Price R, Zapka J, Edwards H, Taplin SH. Organizational factors and the cancer screening process. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;(40):52–71. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):126–153. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):281–315. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lanier D, Clancy C. The changing interface of primary and specialty care. J Fam Pract. 1996;42(3):303–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.AHCPR. Research at the Interface of Primary and Specialty Care. Conference Summary Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. Report No.: AHCPR 96-0034. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Mani S, et al. Timely follow-up of abnormal diagnostic imaging test results in an outpatient setting: are electronic medical records achieving their potential? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1578–1586. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, Fanjiang G, editors. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meissner HI, Vernon SW, Rimer BK, et al. The future of research that promotes cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101(5) suppl:1251–1259. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nekhluyudov L, Latosinsky S. The interface of primary and oncology specialty care: from symptoms to diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;(40):11–17. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fazili J, Ilagan M, Phipps E, Braitman LE, Levine GM. How gastroenterologists inform patients of results after lower endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):2086–2092. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rubin DT, Ulitsky A, Poston J, Day R, Huo D. What is the most effective way to communicate results after endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(1):108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taplin SH, Haggstrom D, Jacobs T, et al. Implementing colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: comprehensive approaches to screening that address health disparities. Med Care. 2009;46(9):574–583. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spodik M, Goldman J, Merli K, Walker C, Alpini B, Kastenberg D. Providing an endoscopy report to patients after a procedure: a low-cost intervention with high returns. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(1):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCaffery KJ, Irwig L, Chan SF, et al. HPV testing versus repeat Pap testing for the management of a minor abnormal Pap smear: evaluation of a decision aid to support informed choice. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):473–479, 481. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ritvo P, Myers R, Del Giudice ML, et al. Factorial validity and invariance of a survey measuring psychosocial correlates of colorectal cancer screening in ontario, Canada—a replication study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):3279–3283. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hahn KA, et al. Self-report versus medical records for assessing cancer-preventive services delivery. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2987–2994. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murray DM, Pennell M, Rhoda D, Hade EM, Paskett ED. Designing studies that would address the multilayered nature of health care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;(40):90–96. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brewer NT, Salz T, Lillie SE. Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):502–510. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blomberg K, Forss A, Ternestedt BM, Tishelman C. From ‘silent’ to ‘heard’: professional mediation, manipulation and women's experiences of their body after an abnormal Pap smear. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(3):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]