Abstract

Objective

To estimate the effect of exclusive breast feeding and partial breast feeding on infant mortality from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections in Latin America.

Design

Attributable fraction analysis of national data on infant mortality and breast feeding.

Setting

Latin America and the Caribbean.

Main outcome measures

Mortality from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections and nationally representative breastfeeding rates.

Results

55% of infant deaths from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections in Latin America are preventable by exclusive breast feeding among infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding throughout the remainder of infancy. Among infants aged 0-3 months, 66% of deaths from these causes are preventable by exclusive breast feeding; among infants aged 4-11 months, 32% of such deaths are preventable by partial breast feeding. 13.9% of infant deaths from all causes are preventable by these breastfeeding patterns. The annual number of preventable deaths is about 52 000 for the region.

Conclusions

Exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding throughout the remainder of infancy could substantially reduce infant mortality in Latin America. Interventions to promote breast feeding should target younger infants.

What is already known on this topic

Infant mortality is lower among breast fed than non-breast fed infants

The reductions are greatest for deaths from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections

What this study adds

Exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding for the remainder of the first year would prevent about 52 000 infant deaths a year in Latin America

This corresponds to 13.9% of infant deaths from all causes

Promotion of breast feeding has an important role in increasing survival of infants

Introduction

The low prevalence and duration of exclusive and partial breast feeding increase the risk of infant and childhood morbidity and mortality in both developed and developing countries.1–4 The risk is highest for diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections.

Published studies of the effects of breast feeding have several shortcomings. Generally, researchers have analysed breast feeding as a dichotomous variable. Sometimes the breastfeeding group was not clearly defined or was inconsistent with commonly used indicators. Although the mortality risk of not breast feeding has been shown to be highly age dependent,1,5 most studies have not differentiated high risk infants from low risk infants.6–10 Consequently, it is difficult to quantify the benefits of exclusive breast feeding or to compare the effect of promoting breast feeding during early infancy with similar interventions targeted at older infants.

We investigated the potential of exclusive breast feeding during the first four months of life and partial breast feeding throughout the remainder of infancy to reduce infant mortality in Latin America and the Caribbean (henceforth referred to as Latin America). Our estimates take into account differing risk according to age and breastfeeding pattern.

Methods

Data on breast feeding

We obtained breastfeeding rates from recent nationally representative surveys for 16 of 36 countries in Latin America. With the exception of Cuba and Chile,11,12 country data were extracted from the demographic and health surveys from Macro International (Calverton, MD) or reports of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (references available from the authors). We calculated country level rates of breast feeding by age group as infant population weighted averages of age specific feeding rates. We calculated regional and subregional rates as infant population weighted averages of country rates. Infant population figures and subregional and regional classifications were based on those of the United Nations.13

For infants in the first four months of life (aged 0-3 months) the categories were exclusive breast feeding, partial breast feeding, and no breast feeding, and for infants aged 4-11 months (4 months to under 1 year) the categories were partial breast feeding and no breast feeding. Exclusive breast feeding means no other liquids or solids except vitamins, mineral supplements, or medicines. Partial breast feeding means receiving some breast milk, regardless of how much.14 We chose to analyse exclusive breast feeding among infants aged 0-3 months because relatively few older infants in Latin America are exclusively breast fed.14

Mortality data

We used attributable risk methods to calculate the fraction of deaths from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections that could be prevented by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breastfeeding during the remainder of infancy.15,16 Relative risks of death from these diseases for the feeding categories (table 1) were obtained from a reanalysis of published data2 to match the age groups analysed (A Barros, personal communication). Except as noted below, data on all cause and cause specific child and infant mortality and of age distribution of child and infant mortality were regional estimates or other aggregates. We assumed that these estimates applied at country level.

Table 1.

Relative risks of death from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections by age and breastfeeding category

| Exclusive breast feeding | Partial breast feeding | No breast feeding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoeal disease: | |||

| 0-3 months | 1.0 | 4.1 | 15.1 |

| 4-11 months | NA | 1.0 | 2.2 |

| Acute respiratory infections: | |||

| 0-3 months | 1.0 | 2.9 | 4.0 |

| 4-11 months | NA | 1.0 | 2.1 |

NA=not applicable.

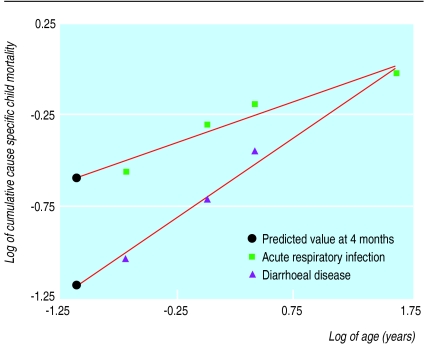

In 1990, the proportion of deaths in children under 5 years old in Latin America from diarrhoeal disease was 18.4% and from acute respiratory infections was 14.1%.17 We estimated the proportion of deaths in children under 5 that occurred in infancy as the ratio of the country specific probability of dying before age 1 year and dying before age 5 years.18 Half of deaths from diarrhoeal diseases in children under 5 occurred during the first year of life, as did three quarters of deaths from acute respiratory infections.19 To predict cause specific mortality at 4 months of age, we plotted estimates of cause specific child mortality by age19 and fitted them by log-log simple least squares regression (figure). The proportions of infant deaths from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections occurring among infants aged 0-3 months were estimated as 0.62 and 0.75, respectively.

To calculate the fractions of mortality preventable by breast feeding in each infant age group as a proportion of all cause infant mortality, we multiplied the cause and age specific attributable fractions by the cause specific proportions of all cause mortality for the age group. To estimate the fraction of infant mortality from the studied diseases occurring during the first year of life that was preventable by breast feeding, we calculated a weighted average of the preventable fractions for each infant age group, where weights were the proportions of mortality from diarrhoeal disease or acute respiratory infections occurring in the age groups. We used the same method to calculate the preventable fraction of mortality from both diseases in the first year of life, using the proportions of mortality from both causes as the weights. Subregional and regional results were calculated with subregional and regional population figures13 and infant population weighted averages of rates.

For example, for Bolivia among infants aged 0-3 months, the rate of exclusive breast feeding was 0.60, partial breast feeding 0.38, and no breast feeding 0.02 (see table 2). These rates and the corresponding relative risks for diarrhoeal disease from table 1 (4.1 and 15.1) give an age specific attributable fraction (proportion of preventable mortality) for diarrhoeal disease of:

|

This figure was multiplied by the age specific fraction of infant mortality from diarrhoeal disease (0.086, calculations not shown) to calculate deaths from diarrhoeal diseases that are preventable by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months as a proportion of infant deaths from all causes (0.59×0.086=0.050). We used a similar procedure to calculate the mortality from diarrhoeal disease preventable by partial breastfeeding for the age group 4-11 months.

Table 2.

Age specific breastfeeding rates by country, subregion, and region

| Geographical area | Age 0-3 months

|

Age 4-11 months

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breast feeding | Partial breast feeding | No breast feeding | Partial breast feeding | No breast feeding | ||

| Bolivia | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.90 | 0.10 | |

| Brazil | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Chile | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.46 | |

| Colombia | 0.16 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.34 | |

| Cuba | 0.14 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.78 | |

| Dominican Republic | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 0.47 | |

| Ecuador | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.15 | 0.73 | 0.27 | |

| El Salvador | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.76 | 0.24 | |

| Guatemala | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.09 | |

| Haiti | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 0.09 | |

| Honduras | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.17 | |

| Mexico | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.49 | |

| Nicaragua | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.33 | |

| Paraguay | 0.07 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |

| Peru | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.09 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.58 | |

| Caribbean | 0.13 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.58 | 0.42 | |

| Central America | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.40 | |

| South America | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.60 | 0.40 | |

| Latin America | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.14 | 0.60 | 0.40 | |

To calculate the attributable fraction of mortality from diarrhoeal disease in all infants, we added the attributable fraction of mortality from diarrhoeal disease in infants aged 0-3 months of age (0.59), multiplied by the fraction of mortality from diarrhoeal disease in this age group (0.62), to the attributable fraction of mortality from diarrhoeal disease in infants aged 4-11 months (0.11), multiplied by the fraction of mortality from diarrhoeal disease in that age group (0.38), giving a value of 0.4. The number of deaths from diarrhoeal disease in Bolivia that could be prevented by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding during the remainder of infancy was obtained by summing both age groups' preventable fractions (0.050+0.006=0.056) and multiplying the sum by the total number of infant deaths in Bolivia. Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 97.

Sensitivity analysis

We allowed some estimates to vary in order to show how subregional and regional results respond to possible errors in estimation or modelling assumptions. The selected variables were breastfeeding rates, relative risks, cause specific proportions of mortality in children under 5, the proportion of deaths in children under 5 that occurred in infancy, cause specific proportions of mortality in children under 5 occurring in infancy, and cause specific proportions of infant mortality occurring during the first four months of life.

We used the spreadsheet program @RISK (Palisade Corporation, Newfield, NY) for the sensitivity analysis. Distributions were defined so that either the mean or the mode corresponded with our estimates, and standard deviations so that the 5th and 95th percentiles bracketed most reasonable variation. Uncertainty is represented by reporting the 5th and 95th percentiles of the distributions of the analysed results.

Results

The infant population covered by this study was 87.2% for the Caribbean subregion, 95.6% for central America, and 82.1% for South America.13 Table 2 gives the age specific breastfeeding rates by country, subregion, and region.

Table 3 gives age specific estimates of mortality from diarrhoeal disease that could be prevented by breast feeding as both cause specific and all cause attributable fractions. Estimates of preventable mortality for infants aged 0-3 months ranged from 0.84 in Cuba to 0.57 in Peru. About half of preventable infant deaths from diarrhoeal disease occurred in Brazil and Mexico, the most populous countries in Latin America.

Table 3.

Annual age specific mortality from diarrhoeal disease in Latin America that is preventable by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding for remainder of first year. Results are presented as attributable proportions of deaths from diarrhoeal disease and deaths from all causes

| Geographical area | 0-3 months

|

4-11 months

|

0-11 months

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoeal disease | All cause | Diarrhoeal disease | All cause | Diarrhoeal disease | All cause | No of preventable deaths | |||

| Bolivia | 0.59 | 0.050 | 0.11 | 0.006 | 0.40 | 0.056 | 776 | ||

| Brazil | 0.78 | 0.052 | 0.37 | 0.015 | 0.62 | 0.068 | 9223 | ||

| Chile | 0.68 | 0.047 | 0.36 | 0.015 | 0.56 | 0.062 | 144 | ||

| Colombia | 0.76 | 0.053 | 0.29 | 0.012 | 0.58 | 0.065 | 1188 | ||

| Cuba | 0.84 | 0.067 | 0.48 | 0.024 | 0.70 | 0.090 | 103 | ||

| Dominican Republic | 0.79 | 0.052 | 0.36 | 0.015 | 0.63 | 0.067 | 546 | ||

| Ecuador | 0.79 | 0.074 | 0.25 | 0.014 | 0.58 | 0.088 | 583 | ||

| El Salvador | 0.78 | 0.054 | 0.23 | 0.010 | 0.57 | 0.063 | 365 | ||

| Guatemala | 0.63 | 0.062 | 0.09 | 0.006 | 0.43 | 0.068 | 767 | ||

| Haiti | 0.77 | 0.071 | 0.09 | 0.005 | 0.51 | 0.077 | 1271 | ||

| Honduras | 0.70 | 0.048 | 0.17 | 0.007 | 0.50 | 0.055 | 349 | ||

| Mexico | 0.83 | 0.058 | 0.37 | 0.016 | 0.65 | 0.074 | 3528 | ||

| Nicaragua | 0.76 | 0.070 | 0.28 | 0.016 | 0.58 | 0.085 | 407 | ||

| Paraguay | 0.79 | 0.054 | 0.27 | 0.011 | 0.59 | 0.066 | 285 | ||

| Peru | 0.57 | 0.051 | 0.09 | 0.005 | 0.39 | 0.056 | 1036 | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0.82 | 0.059 | 0.41 | 0.018 | 0.67 | 0.077 | 13 | ||

| Caribbean (90% CI) | 0.80 (0.62 to 0.88) | 0.067 (0.040 to 0.101) | 0.33 (0.10 to 0.56) | 0.017 (0.005 to 0.037) | 0.62 (0.41 to 0.75) | 0.084 (0.051 to 0.125) | 2582 (1571 to 3826) | ||

| Central America (90% CI) | 0.81 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.070 (0.041 to 0.103) | 0.33 (0.09 to 0.55) | 0.017 (0.005 to 0.038) | 0.62 (0.40 to 0.74) | 0.087 (0.052 to 0.127) | 8435 (5017 to 12 321) | ||

| South America (90% CI) | 0.75 (0.42 to 0.86) | 0.053 (0.025 to 0.081) | 0.33 (0.10 to 0.55) | 0.014 (0.004 to 0.031) | 0.59 (0.31 to 0.73) | 0.067 (0.034 to 0.102) | 15 620 (7937 to 23 887) | ||

| Latin America (90% CI) | 0.78 (0.51 to 0.87) | 0.056 (0.030 to 0.085) | 0.33 (0.09 to 0.55) | 0.014 (0.004 to 0.032) | 0.61 (0.35 to 0.73) | 0.071 (0.039 to 0.106) | 26 590 (14 485 to 39 673) | ||

Table 4 gives estimates of preventable deaths from acute respiratory infections. Estimates for infants aged 0-3 months ranged from 0.66 in Trinidad and Tobago to 0.43 in Peru. Again, about half of preventable infant deaths occurred in Brazil and Mexico.

Table 4.

Annual age specific mortality from acute respiratory infections in Latin America that is preventable by by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding for remainder of first year. Results are presented as attributable proportions of deaths from acute respiratory infection and deaths from all causes

| Geographical area | 0-3 months

|

4-11 months

|

0-11 months

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute respiratory infection | All cause | Acute respiratory infection | All cause | Acute respiratory infection | All cause | No of preventable deaths | |||

| Bolivia | 0.44 | 0.052 | 0.10 | 0.004 | 0.35 | 0.056 | 776 | ||

| Brazil | 0.56 | 0.053 | 0.35 | 0.011 | 0.51 | 0.064 | 8707 | ||

| Chile | 0.45 | 0.043 | 0.34 | 0.011 | 0.42 | 0.053 | 124 | ||

| Colombia | 0.62 | 0.060 | 0.27 | 0.009 | 0.53 | 0.069 | 1261 | ||

| Cuba | 0.65 | 0.072 | 0.46 | 0.017 | 0.61 | 0.089 | 102 | ||

| Dominican Republic | 0.61 | 0.056 | 0.34 | 0.010 | 0.54 | 0.067 | 544 | ||

| Ecuador | 0.60 | 0.077 | 0.23 | 0.010 | 0.51 | 0.087 | 578 | ||

| El Salvador | 0.62 | 0.059 | 0.21 | 0.007 | 0.52 | 0.066 | 381 | ||

| Guatemala | 0.49 | 0.067 | 0.09 | 0.004 | 0.39 | 0.071 | 801 | ||

| Haiti | 0.65 | 0.084 | 0.09 | 0.004 | 0.51 | 0.088 | 1455 | ||

| Honduras | 0.53 | 0.051 | 0.16 | 0.005 | 0.44 | 0.056 | 355 | ||

| Mexico | 0.60 | 0.058 | 0.35 | 0.011 | 0.54 | 0.070 | 3321 | ||

| Nicaragua | 0.59 | 0.075 | 0.26 | 0.011 | 0.51 | 0.086 | 411 | ||

| Paraguay | 0.65 | 0.062 | 0.25 | 0.008 | 0.55 | 0.070 | 305 | ||

| Peru | 0.43 | 0.054 | 0.09 | 0.004 | 0.34 | 0.057 | 1053 | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0.66 | 0.065 | 0.39 | 0.013 | 0.59 | 0.078 | 14 | ||

| Caribbean (90% CI) | 0.64 (0.53 to 0.73) | 0.075 (0.050 to 0.093) | 0.32 (0.08 to 0.54) | 0.012 (0.003 to 0.028) | 0.56 (0.39 to 0.66) | 0.087 (0.059 to 0.111) | 2659 (1803 to 3394) | ||

| Central America (90% CI) | 0.58 (0.45 to 0.69) | 0.071 (0.045 to 0.089) | 0.31 (0.08 to 0.54) | 0.012 (0.003 to 0.029) | 0.52 (0.35 to 0.63) | 0.083 (0.053 to 0.108) | 8013 (5129 to 10 413) | ||

| South America (90% CI) | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.66) | 0.054 (0.035 to 0.070) | 0.31 (0.08 to 0.54) | 0.010 (0.003 to 0.023) | 0.50 (0.32 to 0.61) | 0.064 (0.042 to 0.085) | 15 038 (9787 to 19 882) | ||

| Latin America (90% CI) | 0.57 (0.44 to 0.68) | 0.058 (0.037 to 0.074) | 0.31 (0.08 to 0.54) | 0.010 (0.003 to 0.024) | 0.51 (0.33 to 0.62) | 0.068 (0.044 to 0.089) | 25 571 (16 626 to 33 388) | ||

By calculating a weighed average of information from tables 3 and 4, we estimated that in Latin America 55% (90% confidence interval 36% to 66%) of infant deaths from both diseases are preventable by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding throughout the remainder of infancy (61% of deaths from diarrhoeal disease and 51% from acute respiratory infections). Among infants aged 0-3 months, 66% (48% to 76%) of deaths from both diseases are preventable by exclusive breast feeding (78% of deaths from diarrhoeal disease and 57% from acute respiratory infections); among infants aged 4-11 months, 32% (10% to 51%) of deaths from both diseases are preventable by partial breast feeding (33% of deaths from diarrhoeal disease and 31% from acute respiratory infections). In total, 13.9% (8.8% to 18.5%) of all infant deaths in Latin America are preventable by this pattern of breast feeding, which corresponds to 52 161 (33 098 to 69 320) deaths.

Discussion

Promotion of breast feeding is an important intervention for reducing infant mortality.6,20,21 Our analysis suggests that 13.9% of all cause infant mortality in Latin America (some 52 000 deaths annually) could be prevented by exclusive breast feeding of infants aged 0-3 months and partial breast feeding throughout the remainder of the first year. Most of the potential reduction in mortality is among infants aged 0-3 months. As the patterns of infant mortality differ between countries, child survival strategies might need to be tailored to specific groups or practices in different countries.

Accuracy of estimates

Our estimates are both conservative and liberal in some regards. We assumed that the excess risk of mortality is independent across the two infant age groups. However, if breast feeding improves long term nutritional status and immune functioning, children who are breast fed in early infancy may have a lower risk of death thereafter. On the other hand, we ignored competing causes of mortality. Some of the 52 000 infants a year who did not die from diarrhoeal disease or acute respiratory infections would die from other causes.

We assumed full compliance with the specified breastfeeding patterns. Shifting all infants to the described breastfeeding group produces the theoretical maximum possible effect. Studies in Latin America suggest that promotion of breast feeding can realistically give a 25% shift (moving a quarter of infants in each increased risk category to the corresponding no risk category).22–24 Such a shift would prevent around 13 000 deaths (a quarter of our estimate).

Our estimates of the proportions of infant deaths from diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infections occurring during the first four months of life are consistent with observations of age and cause specific mortality in children19,25 and results from population based survivorship models.26,27 Although the figures are likely to be good approximations at the regional and subregional level, possible variation across countries is ignored.

The relative risks of death associated with feeding category may also be subject to regional variation. Various estimates have been published of relatives risk,2,7,28,29 none of which is ideal for this case. We used reanalysed estimates from the Brazilian study2 because it was population based, conducted in one of the countries in the region, investigated the relevant causes of death, applied a consistent protocol for assigning cause of death, excluded infant deaths subject to known or suspected confounding factors, and coded feeding status before the onset of fatal illness. Nevertheless, there may be variations in local risk patterns that we could not account for. Although differences between urban and rural areas could be a source of bias,30 at the aggregate level they are unlikely to affect estimates substantially.21 Another reason for using the Brazilian estimates was that the study controlled for factors such as prematurity, low birth weight, and congenital malformations, which increase the risk of death as well as reducing the probability of breast feeding.31 Surveys of rates of breast feeding, however, do not control for these factors.

These limitations, which are common to this type of study, highlight the need for a sensitivity analysis. However, we found uncertainty ranges to be remarkably stable under varying assumptions, and even the lower bounds indicate that promotion of breast feeding should be prominent in child survival strategies for Latin America.

Cultural differences in ideas about breast feeding should not seriously affect the analysis. Since the demographic and health surveys collect data using internationally accepted indicators, assignment to feeding category does not rely primarily on respondents' understanding of breast feeding but on detailed questions about food and fluid intake.

Implications

Our data are useful for comparing promotion of breast feeding with other child survival strategies. Although our methods are suitable for global analysis, we selected Latin America because it had the highest availability of data. Improved breastfeeding rates are likely to have less effect in areas where higher proportions of infants are breast fed (such as rural Africa) and more effect in areas where early weaning is common (such as South East Asia). Nevertheless, since exclusive breast feeding remains uncommon in many countries, improving rates of exclusive breast feeding in early infancy would probably substantially reduce infant mortality worldwide.

Our analysis suggests that interventions to promote breast feeding should particularly target younger infants and focus on exclusive breast feeding. Programmes such as the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative have been important in improving the rates of successful initiation of exclusive breast feeding.32 The challenge is to provide adequate and comprehensive support to mothers so that they can continue exclusive breast feeding while coping with the demands and strains of daily life.33

Figure.

Log–log plot of cumulative cause specific child mortality by age, showing data points for ages 6 months, 1 year, 1.5 years, and 5 years19 and predicted values at 4 months

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the World Health Organization. We thank Edward Frongillo and Cesar Victora for their comments and Aluiso Barros for providing the reanalysed relative risks.

Footnotes

Contributors: APB and MdO had the original idea and initiated the research. With JV they conceptualised the study and epidemiological strategy. All authors contributed to study design, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing and revision of the manuscript. In addition, JAL did the sensitivity analysis. APB is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Puffer RR, Serrano CV. Patterns of mortality in childhood. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Lombardi C, Fuchs SM, Gigante LP, Smith PG, et al. Evidence for protection by breastfeeding against infant deaths from infectious diseases in Brazil. Lancet. 1987;ii:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown KH, Black RE, Lopez de Romaña G, Creed de Kanashiro H. Infant feeding practices and their relationship with diarrheal and other diseases in Huascar (Lima), Peru. Pediatrics. 1989;83:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2000;355:451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martines JC, Habicht JP, Ashworth A, Kirkwood BR. Weaning in southern Brazil: is there a “weanling's dilemma”? J Nutr. 1994;124:1189–1198. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.8.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feachem RG, Koblinsky MA. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: promotion of breastfeeding. Bull World Health Organ. 1984;62:271–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachdev HPS, Kumar S, Singh KK, Satyanarayana L, Puri RK. Risk factors for fatal diarrhea in hospitalized children in India. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:76–81. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199101000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victora CG. Infection and disease: the impact of early weaning. Food Nutr Bull. 1996;17:390–396. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golding J, Emmett PM, Rogers IS. Breast feeding and infant mortality. Early Hum Dev. 1997;49(suppl 1):143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(97)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victora CG, Kirkwood BR, Ashworth A, Black RE, Rogers S, Sazawal S, et al. Potential interventions for the prevention of childhood pneumonia in developing countries: improving nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:309–320. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amador M, Silva LC, Uriburu G, Valdés F. Caracterización de la lactancia materna en Cuba. Food Nutr Bull. 1992;14:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castillo C, Atalah E, Riumano J, Castro R. Breastfeeding and the nutritional status of nursing children in Chile. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1996;30:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations. World population prospects. The 1994 revision. New York: United Nations; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. The WHO global data bank on breast-feeding. Geneva: Switzerland; 1996. . (WHO/NUT/96.1.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole P, MacMahon B. Attributable risk percent in case-control studies. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1971;25:242–244. doi: 10.1136/jech.25.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouellet B, Romeder JM, Lance JM. Premature mortality attributable to smoking and hazardous drinking in Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:451–463. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global health statistics: a compendium of incidence, prevalence and mortality estimates for over 200 conditions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. . (Global burden of disease and injury series, vol 2.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez AD, Salomon J, Ahmad O, Murray CJL. Life table for 191 countries: data, methods and results. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. . (GPE discussion paper No 9.) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkwood BR, Gove S, Rogers S, Lob-Levyt J, Arthur P, Campbell H. Potential interventions for the prevention of childhood pneumonia in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:793–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monteiro CA, Rea M, Victora CG. Can infant mortality be reduced by promoting breastfeeding? Evidence from São Paulo city. Health Policy Plan. 1990;5:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huffman SL, Yeager BAC, Levine RE, Shelton J, Labbok M. Breastfeeding saves lives: an estimate of the impact of breastfeeding on infant mortality in developing countries. Bethesda, MD: NURTURE/Center To Prevent Childhood Malnutrition; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popkin BM, Canahuati J, Bailey PE, O'Gara C. An evaluation of a national breastfeeding programme in Honduras. J Biosoc Sci. 1991;23:5–21. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000019027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valdés V, Perez A, Labbok M, Pugin E, Zambrano I, Catalan S. The impact of a hospital and clinic-based breastfeeding promotion programme in the middle class urban environment. J Trop Pediatr. 1993;39:142–151. doi: 10.1093/tropej/39.3.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albernaz E, Giugliani ER, Victora CG. Supporting breastfeeding: a successful experience. J Hum Lact. 1998;14:283–285. doi: 10.1177/089033449801400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garenne M, Ronsmans C, Campbell H. The magnitude of mortality from acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1992;45:180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heligman L, Pollard JH. The age pattern of mortality. J Inst Actuaries. 1980;107:49–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carnes BA, Olshansky SJ, Grahn D. Continuing the search for a law of mortality. Popul Dev Rev. 1996;22:231–264. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Nobre LC, Barros FC. Deaths due to dysentery, acute and persistent diarrhoea among Brazilian infants. Acta Paediatr. 1992;381(suppl):7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon PW, Black RE, Moulton LH, Becker S. Effect of not breastfeeding on the risk of diarrhea and respiratory mortality in children under 2 years of age in Metro Cebu, The Philippines. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1142–1148. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Population Council. Mexico 1987: Results from the demographic and health surveys. Stud Fam Plann. 1990;21:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barros FC, Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Smith PG. Birth weight and duration of breastfeeding: Are the beneficial effects of human milk being overestimated? Pediatr. 1986;78:656–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Protecting, promoting and supporting breast-feeding. The special role of maternity services. A joint WHO/UNICEF Statement. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villar J, Belizan JM. Breastfeeding in developing countries. Lancet. 1981;ii:621–623. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92755-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]