Abstract

CG-rich DNA “reader” proteins that bind non-methylated CpG sequences have emerged as critical factors to the process of cell differentiation and development. In a recent paper in Nature, Ko et al. show that the CXXC domain protein, IDAX, plays a crucial role as a CG-rich DNA-binding factor in the regulation of Ten-Eleven-Translocation 2 (TET2) protein function.

Epigenetic processes are defined by transmissible alterations in gene expression, which are independent of any change in DNA sequence1. A feature of mammalian genomes is the presence of modified cytosines at CpG dinucleotides, the bulk of which are methylated as 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Short stretches (1-2 kb long) of CpG-rich unmethylated DNA stand out as CpG islands (CGIs)1,2. Many CGIs correspond to gene promoter regions, and methylation of an active CGI promoter results in its silencing. An enduring question is, how are differentially methylated regions maintained in cells? The ability of CpG methylation to silence transcription of unique genes and repeat sequences, including retrotransposons, implicates it as an essential participant in the maintenance of cellular identity and genome integrity1. Mitotic heritability of CpG methylation patterns is essential to both processes. Early molecular models depicted DNA methylation as a one-way process, in which methylation removal or reprogramming occurs through DNA replication in the absence or upon the inhibition of DNA methyltransferases. It was difficult to reconcile this model with dynamic gene-specific reactivation in response to signaling pathways, which implied rapid DNA demethylation3.

The DNA methylation field has undergone a sea change following the discovery of secondary and tertiary modifications of cytosine, which are centred on the enzymatic conversion of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and its derivatives, 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), by the Ten-Eleven-Translocation (TET) proteins4,5. In mammals all three proteins, TET1-3, contain the common features of 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)- and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenases in their C-terminal catalytic region. TET1 and TET3 possess an N-terminal CXXC domain, corresponding to a binuclear Zn-chelating domain also found in other chromatin-associated proteins such as DNMT1, CFP1 and MBD12,6. These CXXC domains can mediate interactions with multiple nuclear components including non-methylated CG-rich DNA2. Conversion of 5hmC into 5fC and/or 5caC, may result in their replacement by cytosine (C) via a base excision repair (BER) demethylation pathway5. Work in the frog suggests that the TET3 CXXC domain is critical for its targeting to the promoters of genes that are essential for eye and neural development7. Deletion of the CXXC domain from Xenopus laevis Tet3 (xlTET3) abolishes its ability to occupy target gene promoters, thereby preventing the TET3-driven developmental demethylation event that is normally associated with the activation of these genes. Inhibition of TET1 function in ES cells leads to an increase in 5mC over transcriptional start sites (TSS) of selected genes, alongside a loss of 5hmC at specific promoters and within gene bodies5. TET2 inactivation in hematopoietic progenitor cells blocks myeloid differentiation5. Consequently, a view is emerging that the TET enzymes and 5hmC participate in signaling pathways that dynamically maintain targeted CGIs in a methylation-free state. The ability to bind CGIs via CXXC domains may be an important aspect of TET1 and TET3 targeting. As TET2 lacks a CXXC interaction motif, it might be assumed that the molecular mechanisms for its targeting to DNA promoters are different from those of TET1 and TET3. A landmark paper from the laboratory of Anjana Rao8 suggests otherwise, as an ancestral CXXC protein, IDAX, which became separated from TET2 following chromosomal rearrangement, has a role in both recruiting TET2 to target genes and regulating its protein stability. Approximately 650 kb of DNA separate IDAX (CXXC4) and TET2, which are transcribed in opposite directions. The IDAX protein (367 aa) incorporates a 52-aa CXXC domain that is highly homologous to the CXXC domains of TET1 and TET38. Previously, IDAX was identified as a partner for Dishevelled (DVL1), a cytoplasmic phosphoprotein in the Wingless (Wnt)-Frizzled signaling cascade9.

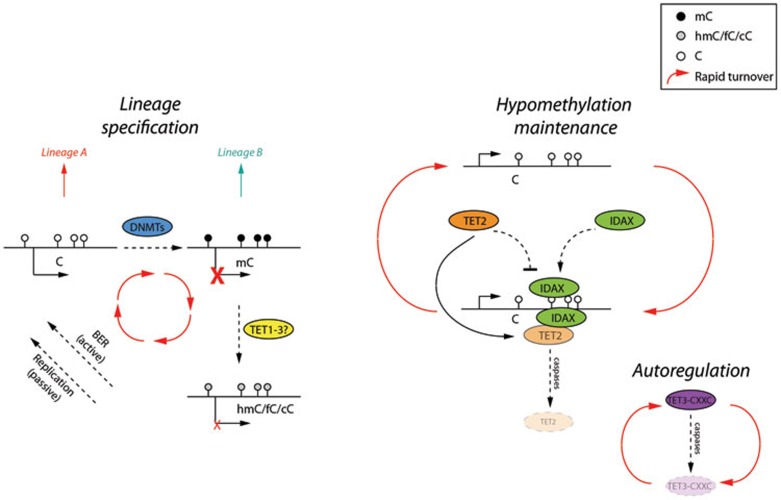

Given these precedents and the similarity between the IDAX and TET1/TET3 CXXC domains, Ko and colleagues8 examined whether IDAX can regulate TET2 function. They demonstrated that IDAX binds non-methylated CG-rich regions in vitro and that ectopically expressed IDAX localized predominantly to CGIs in HEK293T cells. The nuclear localization of IDAX is impaired when the CXXC domain is mutated (IDAXDBM), but both IDAXWT and IDAXDBM interact with TET2 in vitro probably via the catalytic domain. Unexpectedly, co-expression of IDAXWT, but not IDAXDBM, with TET2 results in the disappearance of TET2 protein with a subsequent decrease in 5hmC levels. Neither IDAXWT or IDAXDBM affects TET2 enzyme activity in vitro, and TET2 protein degradation could be inhibited with a pan-caspase inhibitor. These observations suggest that IDAX activity may contribute to differences in TET2 function and 5hmC levels in various tissues. Decrease of TET2 protein, but not TET2 transcripts, during ES cell differentiation was correlated with the appearance of IDAX, and TET2 downregulation can be attenuated by shRNA-mediated inhibition of IDAX. Importantly, ectopic expression of IDAX in haematopoietic precursor cells also leads to downregulation of TET2 and an altered differentiation spectrum towards the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Intriguingly, expression of a TET3 CXXCDBM mutant construct in cells results in higher levels of 5hmC compared to TET3 CXXCWT. These investigations uncover a generality of autoregulation of TET function by extrinsic and intrinsic CXXC protein domains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A simplified model of the recently proposed CXXC-mediated negative regulation of TET enzymes. Left: cellular identity and lineage choice are determined by the balance between active (hypomethylated) and inactive (methylated, by DNMTs) gene promoters, thus yielding two distinct lineages. TET enzymes catalyze the conversion of methylcytosine (mC) to hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC) and further derivatives, formylcytosine (fC) and carboxycytosine (cC), which are eventually recycled back to unmodified cytosine by passive (DNA replication) and active (BER) mechanisms, thus protecting the potential to differentiate to either lineage A or B. Right: recent work from Ko and colleagues8 has revealed a novel autoregulatory mechanism to maintain the hypomethylated state. CXXC DNA-binding domains (in the IDAX and TET3 genes) can bind unmethylated DNA and recruit TET2 (via IDAX) or TET3 (via an integral CXXC domain) for 5mC conversion and at the same time trigger degradation of TET2/3 in a caspase-dependent fashion. This novel property of non-methylated DNA binding CXXC domains in relation to TET enzymes not only functions to dynamically maintain the unmethylated state, but also potentially explains the tissue-specific variation in hydroxymethylated DNA levels. White lollipops, cytosine; black lollipops, mC; and grey lollipops hmC/fC/cC.

What are the implications of these observations? One conceptual advance arising from this mode of regulation is that it may explain the observed tissue-specific differences in 5hmC levels and dynamic changes observed upon differentiation, neoplastic transformation, and environmental exposure5. It sets up additional possible links between well-characterized paracrine cell signaling networks (Wnt pathways) and DNA modification10. The 5hmC story is a narrative that keeps on delivering; long may the excitement continue.

References

- Reddington JP, Pennings S, Meehan RR. Biochem J. 2013. pp. 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Deaton AM, Bird A. Genes Dev. 2011. pp. 1010–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bird A. Nat Immunol. 2003. pp. 208–209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, et al. Science. 2009. pp. 930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Koh KP, Rao A. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013. pp. 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Song J, Rechkoblit O, Bestor TH, et al. Science. 2011. pp. 1036–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Xu C, Kato A, et al. Cell. 2012. pp. 1200–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ko M, An J, Bandukwala HS, et al. Nature. 2013. pp. 122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hino S, Kishida S, Michiue T, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2001. pp. 330–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ruzov A, Hackett JA, Prokhortchouk A, et al. Development. 2009. pp. 723–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]