Abstract

Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (Mlkl) was recently found to interact with receptor interacting protein 3 (Rip3) and to be essential for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced programmed necrosis (necroptosis) in cultured cell lines. We have generated Mlkl-deficient mice by transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)-mediated gene disruption and found Mlkl to be dispensable for normal mouse development as well as immune cell development. Mlkl-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and macrophages both showed resistance to necrotic but not apoptotic stimuli. Mlkl-deficient MEFs and macrophages were indistinguishable from wild-type cells in their ability to activate NF-κB, ERK, JNK, and p38 in response to TNF and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), respectively. Consistently, Mlkl-deficient macrophages and mice exhibited normal interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and TNF production after LPS treatment. Mlkl deficiency protects mice from cerulean-induced acute pancreatitis, a necrosis-related disease, but has no effect on polymicrobial septic shock-induced animal death. Our results provide genetic evidence for the role of Mlkl in necroptosis.

Keywords: Mlkl, necroptosis, apoptosis, TNF, Rip3, mice

Introduction

Necrosis is a type of cell death characterized by morphologic features, including plasma membrane rupture, organelle swelling, mitochondrial dysfunction and cytoplasmic leakage1. Historically, necrosis had been considered as a non-regulated cell death caused by overwhelming external stress. However, a growing body of evidence has indicated that comparable to apoptosis, certain types of necrotic cell death are highly regulated by intrinsically defined mechanisms2,3,4,5,6. Necroptosis was originally used to term receptor interacting protein 1 (Rip1)-dependent necrosis4 and has been used as a synonym of regulated necrosis by some investigators. The necroptosis and apoptosis pathways can influence each other7,8. Rip1-dependent necroptosis does not play a detectable role in embryonic development or tissue homeostasis in mammals. However, it is a trap door that opens when either caspase 8 or FADD is absent9,10. The inhibition of cIAP and activation of CYLD could also promote necroptosis11,12. Necroptosis is also prevalent in a broad range of pathological settings, such as acute bacterial and viral infections, as well as neurodegenerative disorders13,14,15,16,17.

In the early studies of necroptosis, two serine-threonine kinases, Rip1 and Rip3, were identified as the key regulators of necroptosis4,14,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. While Rip1 involvement has been identified in both apoptosis and necroptosis, Rip3 appears to participate solely in necroptosis. Rip3-producing cells are able to execute necroptosis in response to several stimuli under caspase-compromised conditions, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), Fas ligand (FasL), and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL)23,25,26,27. The induction of Rip3 observed in a number of pathological conditions is likely to be the mechanism underlying increased necroptosis in the pathogenesis of these diseases14,24,27,28,29,30,31. In vitro studies have also shown that necroptosis can be induced without caspase inhibition when Rip3 is overexpressed23,32. Rip1 and Rip3 belong to the same kinase family, and both of them contain a C-terminal RHIM domain. During necroptosis induction, Rip1 and Rip3 form a functional amyloid signaling complex through RHIM-RHIM domain interaction33. The assembly of heterodimeric filamentous structures of Rip1-Rip3 complex is believed to be indispensable for necroptosis33. TNF-induced necroptosis is mediated by a signaling complex called necrosome (also known as complex IIb), which contains TRADD, FADD, caspase 8, Rip1 and Rip3. Rip1-Rip3 complex is regarded as the core of necrosome. In the effort to seek novel molecules involved in necroptosis, NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-2 (SIRT2), phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (Mlkl) have been recently revealed as key signaling factors in necroptosis18,32,34,35,36. Identified as a target of necrosulfonamide (NSA), a new inhibitor of necroptosis in human cells32, Mlkl, has been demonstrated to associate with Rip3 and to be phosphorylated by Rip3 during the induction of necroptosis. Furthermore, mechanistic analysis has established that the phosphorylation of Mlkl by Rip3 is required for Rip3-dependent necroptosis32,36.

In order to provide genetic evidence for the essential role of Mlkl in necroptosis, we generated Mlkl knockout mice using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)-mediated gene disruption in this study. The Mlkl-deficient mice are viable, healthy, fertile and do not show any abnormities in development. Mlkl deficiency inhibits necroptosis considerably in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and peritoneal macrophages induced by a panel of necroptotic stimuli, whereas it has no effect on apoptosis. Moreover, knockout of Mlkl ameliorates the severity of cerulean-induced acute pancreatitis in mice, a necroptosis-related disease23,24. However, in the case of diseases with far more complex underlying mechanisms, such as septic shock induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in mice as we showed here, inhibition of necroptosis by Mlkl deficiency is apparently insufficient to alleviate the high mortality rate. Nevertheless, our data presented here have unambiguously established that Mlkl is indeed required for necroptosis in vitro and in vivo and may well play a key role in the pathogenesis of necroptosis-associated diseases.

Results

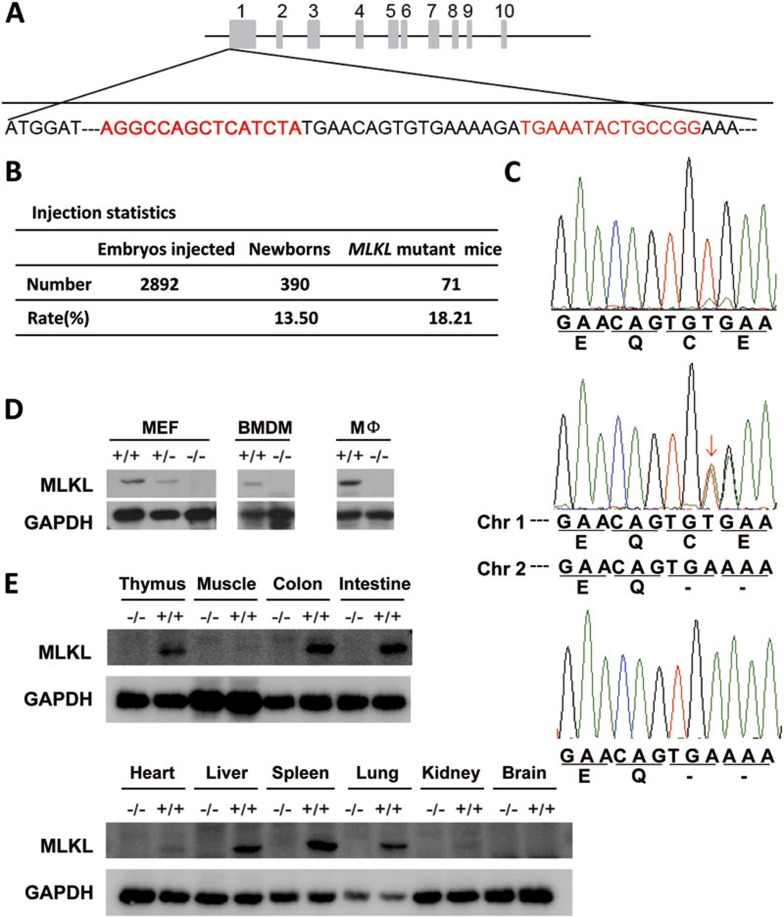

Generation of Mlkl-deficient mice

TALENs-mediated gene mutation is an emerging approach for targeted gene disruption37,38. Because of its similarity to zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs)-mediated gene disruption, the success of using ZFNs to generate gene knockouts in rat and mouse suggests that TALENs can be used to generate highly specific gene knockout mice39,40,41. We constructed TALEN repeats fused with FokI as described38 and subcloned them into pcDNA6.0 vector, which can be used to obtain in vitro-transcribed mRNA. The TALEN repeats that we used were designed to bind the Exon 1 of the Mlkl locus (Figure 1A). In vitro-transcribed mRNA encoding this TALEN pair was microinjected into the male pronuclei of C57BL/6 or Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice zygotes. About 30 injected zygotes were then transferred into the fallopian tube of each recipient ICR mouse. About 18% of the offspring were identified to carry Mlkl mutations in one or both alleles (Figure 1B). Among the 71 mice carrying Mlkl mutations, 4 mice contain mutations in both alleles. In total, nine different deletions occurred at the TALEN targeting site in these 71 mice (Supplementary information, Figure S1). As expected, some of the deletions created frameshift mutations and others did not. A two-base deletion at the 52nd base downstream of ATG site in the Mlkl gene locus was found in 23 mice (Figure 1C). Ten of these 23 mice were on C57BL/6 background and were selected for further breeding and characterization. This two-base deletion created a stop codon and thus truncated Mlkl after Gln17 (Figure 1C). Homozygous Mlkl-deficient (Mlkl−/−) mice are viable, healthy, fertile, born with normal Mendelian frequency and do not display any gross physical or behavioral abnormalities. Western blot using a specific anti-Mlkl antibody verified the absence of Mlkl protein in MEFs, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), peritoneal macrophages and a number of other tissues obtained from Mlkl−/− mice (Figure 1D and 1E). In wild-type mice, the expression level of Mlkl protein is high in thymus, colon, intestine, liver, spleen and lung, while much lower in skeletal muscle, heart and kidney, and is undetectable in the brain. The expression pattern of Mlkl is quite different from that of Rip3 (Supplementary information, Figure S2A). Tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) showed no appreciable morphological difference in heart muscle, liver, spleen and pancreas between wild-type and Mlkl-deficient mice (Figure 6A and Supplementary information, Figure S2B), suggesting that Mlkl is not required for normal development in mice.

Figure 1.

Generation of Mlkl-deficient mice. (A) Targeting strategy for mutation introduction in the exon 1 of Mlkl locus by TALEN. The DNA-binding sites of the TALENs are indicated in red. (B) Summary of the generation of Mlkl-deficient mice. (C) Sequencing chromatograms showing nucleotide mutation introduced in the Mlkl locus adjacent to the FOKI cleavage site. Arrow indicates a double peak. (D) Western blot analysis of Mlkl protein levels in MEFs, BMDMs and peritoneal macrophages (MΦ) obtained from wild-type, Mlkl+/− and Mlkl−/− mice. (E) Western blot analysis of Mlkl protein expression levels in different organs of the wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice.

Figure 6.

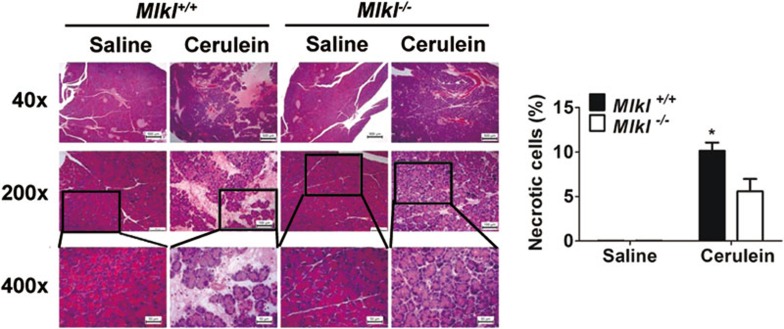

Mlkl dependent necrosis plays a role in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Mlkl knockout (n = 7) and wild-type mouse littermates (n = 7) were given intraperitoneal injections of 50 μg/kg cerulein or saline every hour for 6 consecutive hours, 2 h after the last injection, mice were sacrificed and the pancreas of each mouse were subjected to histological analysis. Pancreatic tissue sections were subjected to H&E staining and analyzed for necrotic cell death. Representative microscopic images of H&E-stained pancreatic sections are shown here with quantitative analyses of cell necrosis in the sections. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. For 40× magnification, the scale bar is 500 μm; 200× magnification, scale bar, 100 μm.

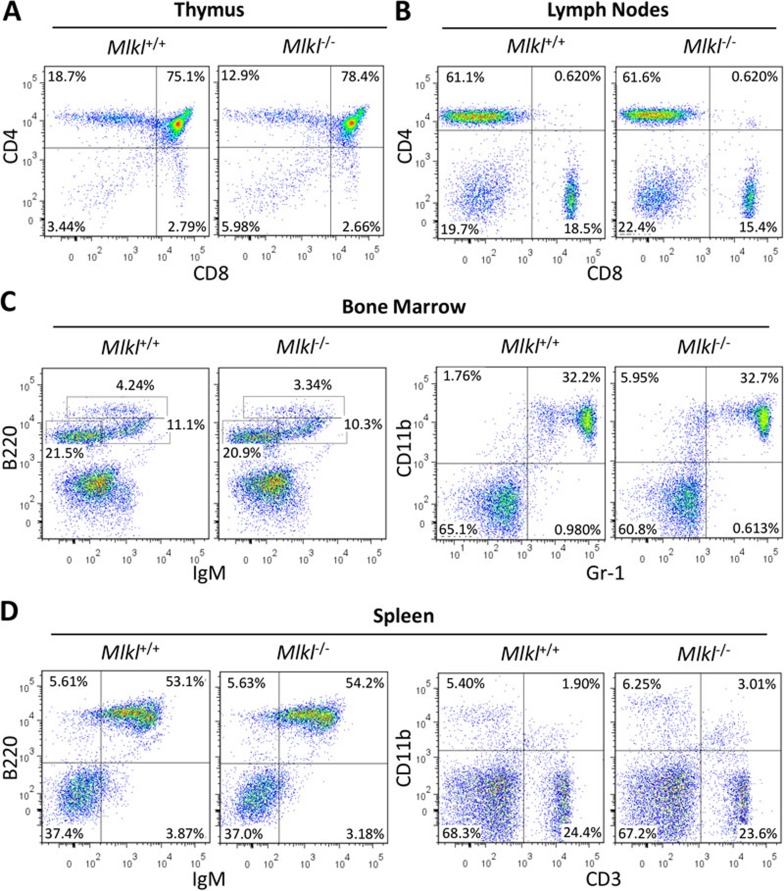

Mlkl is dispensable for the development of T cells, macrophages and neutrophils

We next analyzed whether Mlkl plays a role in immune cell development. Cellular composition in the thymus, lymph nodes, spleen and bone marrow from wild-type and Mlkl−/− mouse littermates was analyzed by flow cytometry after cells were isolated and stained with various immune cell lineage-specific antibodies, as indicated in Figure 2. Analyses of cells stained with CD4 and CD8 antibodies revealed a comparable frequency of mature T lineage cells in the thymus and lymph nodes harvested from wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice (Figure 2A and 2B). B220 and IgM staining of cells from the bone marrow and spleen showed a similar B-cell development pattern in wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice (Figure 2C and 2D). In addition, the frequency of CD11b+ and Gr-1+ neutrophils in bone marrow was normally distributed in Mlkl−/− mice (Figure 2C). Similarly, there was no significant alteration in the proportional distribution of CD3+T cells and CD11b+ macrophages in the spleen of Mlkl−/− mice (Figure 2D). Thus, it appears that there is no detectable abnormality in the development of immune cells in Mlkl-deficient mice.

Figure 2.

T cells, macrophages and neutrophils develop normally in Mlkl knockout mice. Flow cytometric analysis of the cells isolated from the thymus (A), lymph nodes (B), bone marrow (C), and spleen (D) of 8-week-old wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice, respectively. Numbers in each quadrant indicate the percentage of gated cells.

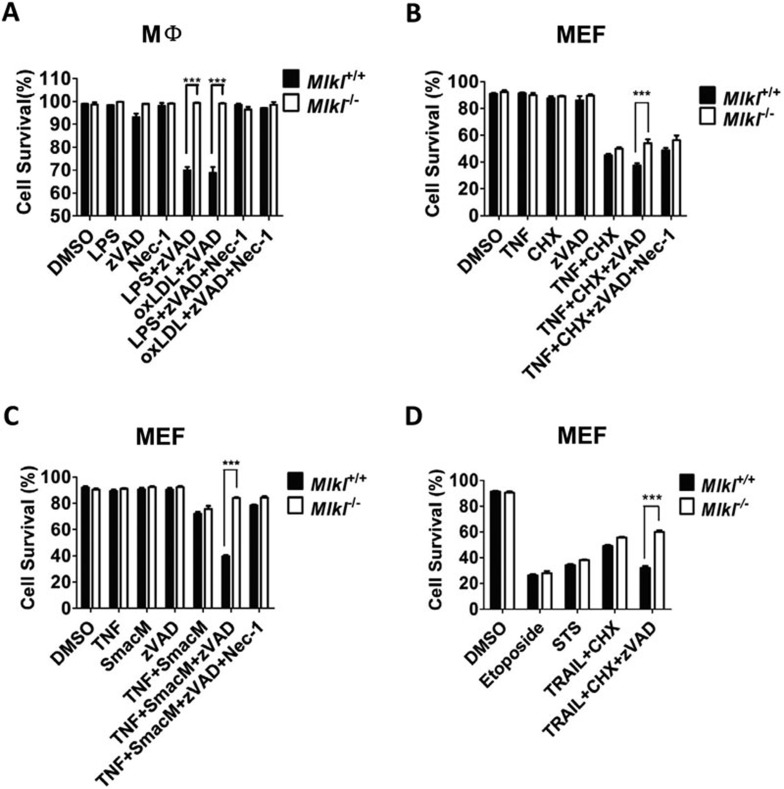

Mlkl plays an essential role in necroptosis of macrophages and MEFs

Mlkl has been recently identified as a critical factor in regulating necroptosis18,32,36. Inhibition of Mlkl by chemical inhibitors or RNAi blocks TNF-induced necroptosis. Here, we investigated whether deletion of Mlkl would alleviate necroptosis. It is known that LPS or pan-caspase inhibitor N-benzyloxycarbonyl-valyl-alanyl-aspartic-acid (O-methyl)-fluoromethylketone (zVAD) alone does not inflict death in macrophages. However, the combined treatment with LPS and zVAD is able to initiate necroptosis23. Similar result was observed with treatment of oxLDL and zVAD27. We isolated peritoneal macrophages from wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice and tested whether Mlkl is required for necroptosis in macrophages. As shown in Figure 3A, Mlkl−/− macrophages were completely resistant to LPS+zVAD- or oxLDL+zVAD-induced necroptosis. As a positive control, necrostatin-1 inhibited cell death. Other than macrophages, we also examined the effect of Mlkl deficiency on cell death in MEFs. Previous studies have shown that treatment of MEF cells with TNF plus cycloheximide (CHX) and zVAD, or TNF plus Smac mimetics (SmacM) and zVAD induced necroptosis14,24, and TNF plus CHX or SmacM without zVAD triggerred apoptotic cell death42,43. Consistent with previous findings that Mlkl was not involved in apoptosis32,36, Mlkl deficiency did not affect either TNF+CHX- or TNF+SmacM-induced cell death in MEFs (Figure 3B and 3C). In agreement with the role of Mlkl in necroptosis, TNF+CHX+zVAD- or TNF+SmacM+zVAD-induced necroptosis was significantly reduced in Mlkl−/− MEFs compared to wild-type MEFs (Figure 3B and 3C), confirming the notion that Mlkl is important for necroptosis, but not for apoptosis. Similarly, while apoptotic cell death induced by TRAIL, another TNF family member, plus CHX was not affected by Mlkl deletion, TRAIL+CHX+zVAD-induced necroptosis was compromised considerably in the absence of Mlkl (Figure 3D). In another case of induced apoptotic cell death, we also found that Mlkl deficiency failed to rescue apoptotic cell death induced by anticancer drug etoposide or staurosporine (STS) in MEFs (Figure 3D). We noticed that the blocking effect of Mlkl deletion on TNF+CHX+zVAD-induced cell death in MEFs was not as complete as that on TNF+SmacM+zVAD-induced necroptosis in MEFs or LPS+zVAD-induced necroptosis in macrophages, suggesting that TNF+CHX+zVAD induces an additional unknown death pathway in MEFs. Collectively, our data unambiguously established an involvement of Mlkl in necroptosis.

Figure 3.

Mlkl is required for necroptosis in MEFs and macrophages. (A) Peritoneal macrophages from wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice were treated as indicated for 24 h with DMSO, LPS (100 ng/ml), zVAD (20 μM), oxLDL (150 μg/ml), LPS+zVAD, or oxLDL+zVAD. Cell viability was determined by Annexin V-Propidium Iodide double-staining. Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1, 30 μM) was included in some samples as a positive control of necroptosis inhibition. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicates. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. (B) Wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEFs were treated with DMSO, TNF (30 ng/ml), CHX (10 μg/ml), zVAD (20 μM), TNF+CHX, or TNF+CHX+zVAD for 8 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicates. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. (C) Wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEFs were treated as indicated for 24 h with DMSO, TNF (30 ng/ml), Smac mimetic (SmacM) (10 nM), zVAD (20 μM), TNF+SmacM, or TNF+SmacM+zVAD. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicates. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. (D) Wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEFs were treated with DMSO, Etoposide (50 μM), staurosporine (STS) (500 nM), TRAIL (20 ng/ml), CHX (10 μg/ml), zVAD (20 μM), or TRAIL+CHX, TRAIL+CHX+zVAD as indicated for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicates. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test.

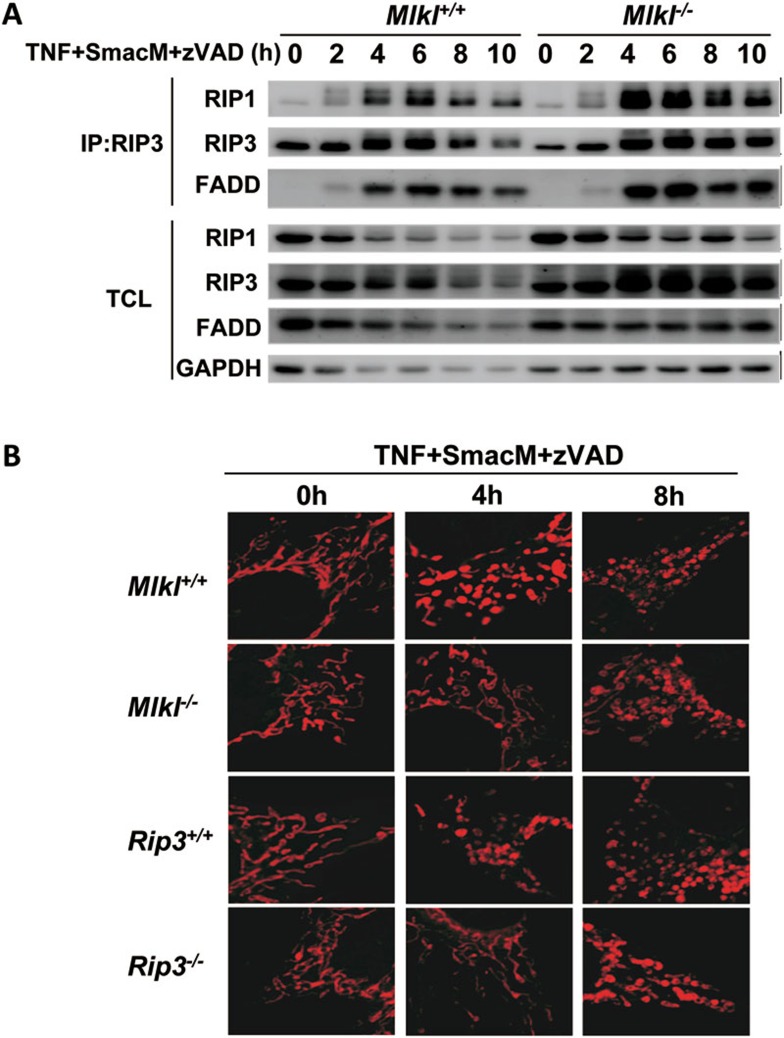

Mlkl mediates signaling downstream of necrosome formation

It has been shown that knockdown of Mlkl does not affect TNF-induced interaction between Rip1 and Rip332. To confirm that Mlkl is not required for necrosome formation, we treated wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEFs with TNF, SmacM and zVAD, followed by immunoprecipitation using an anti-Rip3 antibody at different time points. We were able to detect Rip1 and FADD in the immunoprecipitates of Rip3 at the time points after 4 h of treatment in both wild-type and Mlkl-deficient MEFs (Figure 4A). This indicates that Mlkl is not necessary for necrosome formation. As mitochondrial fission was proposed to be downstream of the necrosome to promote necroptosis35, we analyzed mitochondrial fragmentation in wild-type and Mlkl-deficient MEFs at different time points after TNF+SmacM+zVAD treatment. After necroptotic stimulation, mitochondrial fragmentation appeared at 4 h in wild-type cells, but it was not seen until 8 h in Mlkl-deficient MEFs (Figure 4B). Similar data were obtained using Rip3-deficient cells (Figure 4B). It is difficult to conclude from our data whether mitochondrial fission promotes necroptosis. Nevertheless, Mlkl or Rip3 certainly contributes to the mitochondrial fission during the necroptotic process, and Mlkl appears to be downstream of necrosome formation in the necroptotic pathway.

Figure 4.

Mlkl deficiency does not affect the formation of necrosome, but delays TNF+SmacM+zVAD-induced mitochondria fission. (A) Wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEFs were treated with TNF+SmacM+zVAD for different periods of time, lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Rip3 antibody. The immunoprecipitates and total cell lysates (TCL) were immunoblotted with antibodies as indicated. (B) Wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEFs or wild-type and Rip3−/− MEFs were treated with TNF+SmacM+zVAD for different periods of time. The cells were stained with Mitotracker Red and cell imaging was recorded.

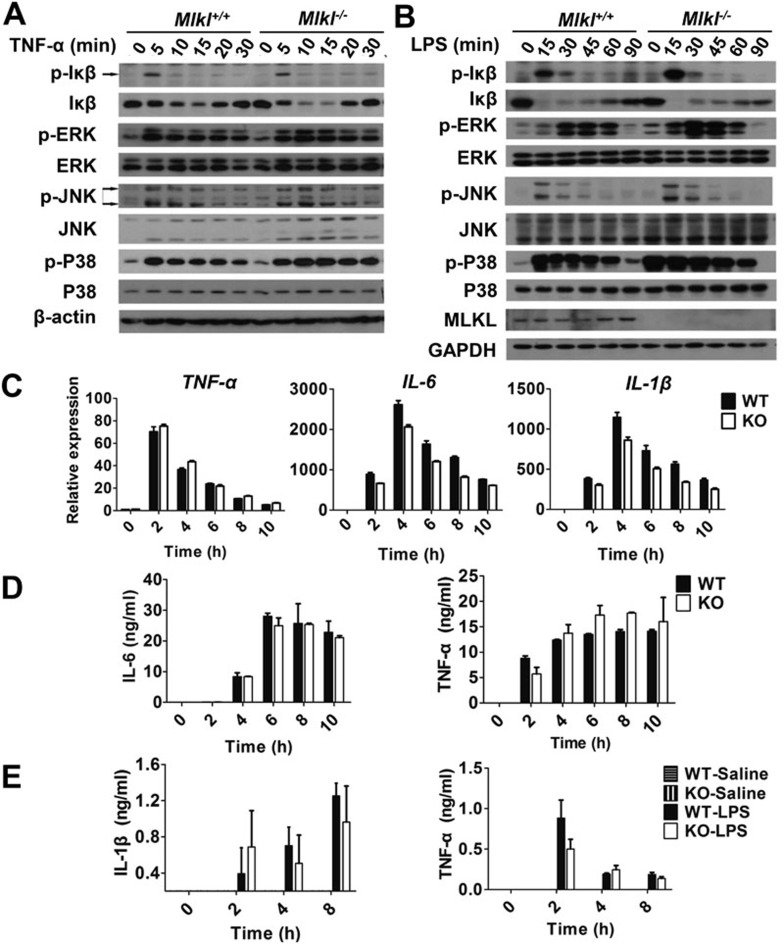

Mlkl is not involved in TNF- or LPS-induced activation of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs)

To investigate whether Mlkl participates in the regulation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling downstream of TNF receptor 1 or Toll like receptor 4, we treated wild-type and Mlkl−/− BMDMs with LPS and MEFs with TNF, and analyzed the activation status of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. The phosphorylation level and degradation progression of IκB were measured to evaluate the activation of NF-κB; the phosphorylation levels of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), c-jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), and p38 were analyzed to determine the activation of these three MAP kinase pathways. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, disruption of Mlkl appeared to have no effect on TNF- or LPS-induced activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways in BMDMs or MEFs, respectively. In addition to the examination of these immediate events induced by LPS or TNF stimulation, we also investigated some of the downstream scenarios, such as cytokine mRNA expression and cytokine secretion. In vitro cultured BMDMs were stimulated with LPS for different periods of time. Levels of TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β mRNA expression (Figure 5C) and TNFα and IL-6 protein secretion (Figure 5D) were measured by real-time RT-PCR and ELISA, respectively. Indeed, we found that there was no statistically significant difference between wild-type and Mlkl-deficient BMDMs in cytokine production, reminiscent of our findings in the early events of NF-κB and MAPK activation upon LPS or TNF stimulation. To evaluate whether Mlkl is required for LPS-stimulated cytokine production in vivo, mice were injected peritoneally with LPS and the levels of TNFα and IL-1β in serum at different time points after injection were measured. Similar to the in vitro data, Mlkl deficiency did not affect LPS-induced TNF and IL-1β expression in mice (Figure 5E). Altogether, our in vitro and in vivo data demonstrated that Mlkl is not required for LPS- and TNF-induced cytokine production, which is similar to the results that Rip3 is not required for LPS- and TNF-induced activation of NF-κB and MAPKs and the subsequent cytokine expression (Supplementary information, Figure S3).

Figure 5.

Mlkl is not involved in activation of NF-κB and MAPKs. (A) Wild-type and Mlkl−/− MEF cells were treated with TNF (20 ng/ml) for the indicated times, and then were analyzed by western blot for p-IκB, IκB, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, p-p38, p38, and β-actin (loading control). (B) BMDMs from wild-type and Mlkl knockout mice were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for different time periods as indicated, and then were analyzed by westen blot for p-IκB, IκB, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, p-p38, p38, and GAPDH (loading control). (C) Expression levels of cytokines in LPS-treated wild-type and Mlkl knockout bone marrow-derived macrophages were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. (D) Expression levels of cytokines in LPS-treated wild-type and Mlkl knockout bone marrow-derived macrophages were analyzed by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of triplicates. (E) Wild-type (n = 4) and Mlkl knockout mice (n = 4) at 8 weeks of age received 30 mg/kg LPS by intraperitoneal injection. The levels of IL-1β, and TNF-α in the serum after injection were measured at the indicated time points by ELISA.

Mlkl deficiency protects mouse from cerulean-induced acute pancreatitis

Rip3-dependent necroptosis was reported to play a pivotal role in various pathophysiological conditions, such as Crohn's disease, atherosclerosis and acute pancreatitis23,24,27,31,44. To determine whether Mlkl also plays a role in the progression of necroptosis-associated diseases, we analyzed wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice in an acute pancreatitis mouse model induced by cerulein stimulation. Wild-type mice injected with cerulein every hour for 6 consecutive hours showed much more severe acinar cell necrosis than Mlkl−/− littermates under the same treatment (Figure 6). Thus, our data demonstrated that Mlkl is indeed involved in necroptosis in vivo and may play a role in the development of necroptosis-associated diseases.

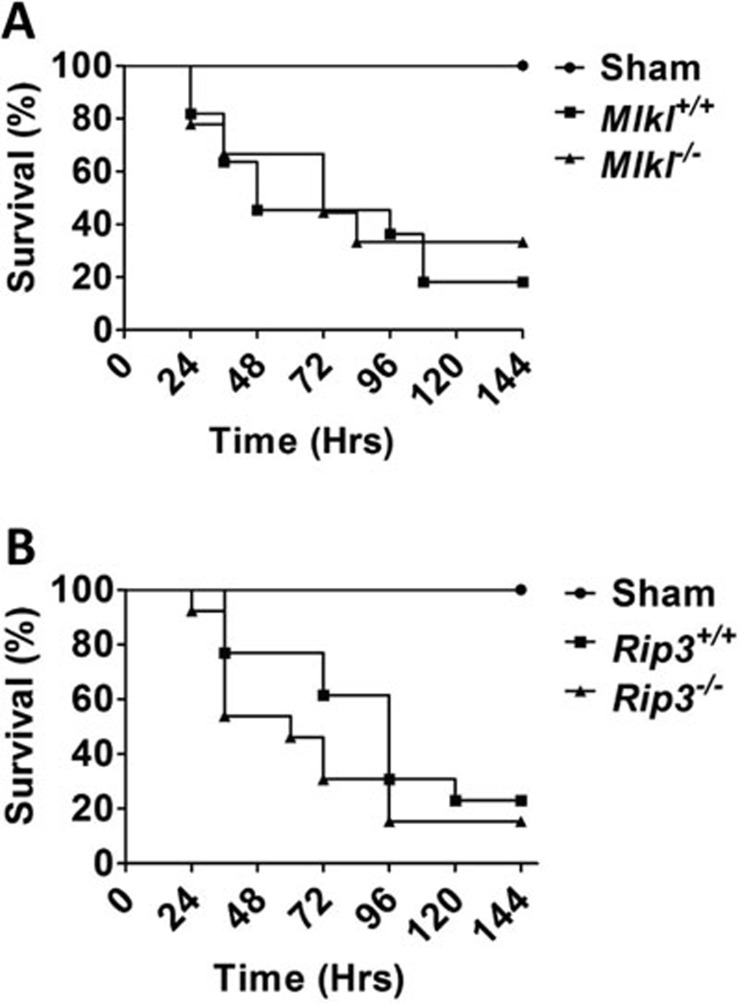

Mlkl or Rip3 deficiency does not provide protection against polymicrobial septic shock-induced animal death in the CLP mouse model

The CLP mouse model is commonly used to study polymicrobial sepsis. It was reported recently that Rip3 knockout mice are resistant to CLP-induced death and thus Rip3-dependent necroptosis was implied to be important for septic shock13. Here, we sought to investigate whether Mlkl deficiency would affect CLP-induced death in mice. Age- and sex-matched littermates of wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice received a 1.5-cm midline laparotomy to allow the exposure of cecum before the ligation of half of the cecum with a silk tie and needle puncture with a 22-gauge needle. Mortality was monitored from 24 h to 144 h after ligation and puncture. Surprisingly, analysis of the survival profile revealed no statistically significant difference between wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice (Figure 7A), which is apparently in conflict with the observations previously reported in Rip3−/− mice13. To further evaluate whether there is any difference between Mlkl−/− and Rip3−/− mice in response to sepsis, we compared the death rate between wild-type and Rip3−/− mice induced by CLP under the same conditions as the experiments described above. As shown in Figure 7B, mortality rate appeared to be the same between wild-type and Rip3−/− mice, which deviated strikingly from the previous report that Rip3 knockout mice were resistant to CLP-induced death13. The data shown in Figure 7 demonstrated that Mlkl−/− mice responded to CLP challenge in a similar manner to Rip3−/− mice. Neither Mlkl nor Rip3 deletion had any effect on the survival rate of mice undergoing CLP procedures.

Figure 7.

Neither Mlkl nor Rip3 deficiency protects mice against CLP-mediated polymicrobial septic shock. (A) The age- and sex-matched littermates of wild-type (n = 10) or Mlkl−/− mice (n = 10) underwent a small midline laparotomy to expose the cecum. The exposed cecum was then ligated and punctured with a needle as described in Materials and Methods. Sham surgery was performed without the procedures of cecal ligation and puncture. There was no significant difference between these two groups. (B) The age- and sex-matched Rip3−/− (n = 18) and wild-type mouse littermates (n = 18) underwent the same protocol as described in (A). Similarly, no significant difference was observed.

Discussion

Identification of Mlkl as an essential component of necrosome to mediate necroptosis has provided valuable information for the delineation of the mechanistic basis of necroptosis32,36. In this report, we generated Mlkl knockout mice using TALENs technique and we further presented genetic evidence that Mlkl is indeed involved in the induction of necroptosis. In agreement with the notion concluded from previous studies conducted in cultured cells that Mlkl appears to be specifically involved in Rip3-dependent necroptosis32,36, Mlkl knockout mice showed essentially the same phenotype as Rip3 knockout mice in the development of acute pancreatitis, a necroptosis-associated disease model in mouse23,24,45. In addition to the in vivo investigation of the role of Mlkl in necroptosis, we also conducted cell culture studies. Compared to wild-type MEFs, TNF/TRAIL+CHX+zVAD- or TNF+SmacM+zVAD-induced necroptosis was reduced in Mlkl−/− MEFs. In contrast, Mlkl deficiency did not affect either TNF/TRAIL+CHX- or TNF+SmacM-induced apoptotic cell death in MEFs. Similar to MEFs, Mlkl−/− macrophages were resistant to LPS+zVAD- or oxLDL+zVAD-induced necroptosis. Taken together, the findings of the present study demonstrate that Mlkl plays a pivotal role in necroptotic pathway, both in vitro and in vivo.

In the study of septic shock induced by CLP, we found that neither Mlkl nor Rip3 deficiency provided protection against polymicrobial sepsis-induced animal death. In a previous report, Rip3 deletion led to a reduction of mortality in mice subjected to CLP13. The conflict on the role of Rip3 in sepsis is not well understood at this stage. It is possible that the intrinsic differences existing in these independent experiments are responsible for the controversy. For example, it is likely that the resident community of cecal bacteria was unique to the experimental animals that were housed in a particular animal facility, which might account for the controversial results in CLP-induced sepsis. In the future, it would certainly be interesting to investigate whether distinct resident cecal bacterial groups would elicit differential host responses in septic shock. Indeed, although the enormous complexity of the systematic inflammatory response in sepsis has been realized for decades, the heterogenic nature of the underlying mechanisms culminating in multiple organ failure at the late stage of sepsis remains largely underappreciated. It is well established that in addition to immunosuppression, cell death also plays a role in the progression of sepsis46. As several cell death modes, including apoptosis, necroptosis, NETosis and pyroptosis, occur simultaneously during the progression of sepsis, there is no conclusive evidence to determine which cell death mode plays a more deleterious role. Thus, it is very likely that in our case, although necroptosis was largely blocked by Mlkl or Rip3 knockout, extensive tissue damage caused by other types of cell death was essentially unaffected and is sufficient to give rise to a high mortality rate in sepsis.

Mlkl has been demonstrated as a substrate of Rip3, but controversial data have been reported on whether Mlkl itself has kinase activity32,36. The sequence of Mlkl is most closely related to the family of mixed lineage kinases, a group of protein kinases that can function as MKKKs, the upstream kinases that regulate the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways47. We showed in Figure 5A and 5B that LPS- and TNF-induced activation of JNK and p38 was not affected by Mlkl deletion, which excluded a role of Mlkl in MAPK activation. Regardless of whether Mlkl acts as a kinase or scaffold protein in the necroptotic pathway, the identification of the signaling effectors downstream of Mlkl would be of great interest in the future for a better understanding of necroptotic signaling cascades.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility. All experiments were conducted in compliance with the regulations of Xiamen University. Rip3−/− mice were produced by targeted gene deletion45.

Generation of Mlkl knockout mice by TALEN

TALEN constructs were linearized at the PVU2 site. In vitro transcripts were generated using T7 Message Max kit (Epicentre, IL, USA) and polyA tailing kit (Epicentre), following the manufacturer's instructions. Washed and dried RNA was dissolved in water, and the concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer. TALEN mRNA was injected into mouse fertilized eggs at 4 ng/μl. Injected eggs were then transferred to pseudopregnant females at 0.5 days post coitum (dpc). New-born mice tail DNA samples were amplified with PrimeStar (Takara, Dalian, China) and the PCR products were sequenced for the screening of heterozygous or knockout descendants.

Antibodies

Anti-Mlkl antibody used in this present study was generated in our lab and immunoaffinity-purified. Anti-JNK (51151-1-AP) antibody was purchased from Proteintech Group (Chicago, IL, USA). Anti-p-IκB (9246), anti-IκB (9242), anti-p-ERK (9101), anti-ERK (9107), anti-p-JNK (9251), anti-p-p38 (4511) and anti-p38 (9228) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-GAPDH (sc-32233) antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA, USA), and anti-β-actin antibody was provided by Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA).

Isolation of mouse BMDMs

Mouse BMDMs were differentiated in vitro from isolated bone marrow cells. Bone marrow cells collected from mouse femurs and tibias were incubated for 7 days in DMEM containing 20% heat-inactivated FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and 30% L929 conditional medium.

Isolation of mouse peritoneal macrophages

Eight-week-old mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1 ml thioglycollate, and peritoneal macrophages were isolated 3 or 4 days later, as described previously. Red blood cells were removed by the ACK lysis buffer. Macrophages were resuspended in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum, and seeded in 12-well plate.

Isolation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Fibroblasts derived from mouse embryos at 2 weeks post coitum were trypsinized and were cultured for two to four passages in 10-cm plates in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum.

In vitro mouse peritoneal macrophage cell death assay

Macrophages were treated with different stimuli as indicated, and cell death was measured by Annexin V-Propidium Iodide double stain kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Macrophages were incubated with Annexin V in binding buffer for 20 min on ice in dark. After Annexin V staining solution was removed, the cells were then stained with propidium iodide for 3 min. Stained cells were immediately analyzed under a fluorescence microscope and four random views were captured for each sample. The Annexin V-Propidium Iodide double-positive cells were defined as necrosis. Annexin V single-positive cells were considered apoptotic.

Flow cytometry

Fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against mouse CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11b, B220, IGM and Gr-1 were used for flow cytometry analysis in this study. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from thymus, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and spleen, respectively, and stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies before the analysis using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer.

Staining of mitochondria

Cells were plated onto glass coverslips and treated as indicated, then stained with Mitotracker Red for 30 min, washed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA. The slides were observed with the Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were treated as indicated, then washed with PBS, lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM Sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml Leupeptin) and immunoprecipitated with protein A/G-sepharose beads crosslinked with anti-Rip3 antibody. Immunocomplexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from mouse macrophages or mouse bone marrow cells by RNA-iso reagent (Takara). Ten micrograms of total RNA were reverse-transcribed using oligo (dT) primer (5′-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (BGI, Shenzheng, China) to generate cDNA. The expression levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and GAPDH mRNA were measured by Real time RT-PCR. Real-time RT-PCR assays were performed using SYBR Green I on CFX96 Real-time RT-PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Primers sequences used in this study are listed as follows: mouse IL-1β (forward: 5′-AAGGGCTGCTTCCAAACCTTTGAC-3′, reverse: 5′-ATACTGCCTGCCTGAAGCTCTTGT-3′), mouse TNF-α (forward: 5′-CCAGTGTGGGAAGCTGTCTT-3′, reverse: 5′-AAGCAAAAGAGGAGGCAACA-3′), mouse IL-6 (forward: 5′-CTGGGAAATCGTGGAAATGAG-3′, reverse: 5′-TCCAGTTTGGTAGCATCCATCA-3′), mouse GAPDH (forward: 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3′, reverse: 5′-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA-3′). PCR was carried out for 35 cycles using the following conditions: denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, annealing at 58 °C for 20 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 20 s.

Western blotting

The cells were cultured in 12-well plates and treated with indicated stimuli. Cells were harvested at different time points and lysed with 1.2× SDS sample buffer, immediately. Total cell lysates were separated using SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore), and western blotting was performed with the appropriate antibodies. The proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (ECL, Millipore).

Cytokine secretion analysis

BMDMs were seeded in 12-well plates, treated with indicated stimuli. Supernatants were collected and measured by commercial ELISA kits for mouse IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β (R&D, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. For in vivo LPS stress, mice were injected with LPS (30 mg/kg) intraperitoneally, and sera were collected before (0 h) and after (2 h, 4 h and 8 h) LPS injection and analyzed for their IL-1β and TNF-α levels by ELISA.

Cerulei-induced acute pancreatitis

Male Mlkl−/− and wide-type mouse littermates at 6-8 weeks of age (n = 7) were treated every hour for 6 consecutive hours with cerulein (50 μg/kg, Sigma) intraperitoneal injection. Animals were sacrificed 2 h after the last injection. Pancreas tissues were removed, fixed, dehydrated, embedded and sectioned. Analysis of pancreatitis-associated pancreas necrotic injury was conducted by H&E staining. Necrosis in eight random microscopic fields per animal was quantitatively analyzed. The acinar cell necrosis criteria were described previously23. All images were captured and processed using identical settings in the Zeiss LSM 780 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope at Xiamen University.

Polymicrobial sepsis induced by CLP in mice

Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with 1% pelltobarbitalum natricum by intraperitoneal injection. The operative procedures were performed under sterile conditions. After disinfection of the abdomen, animals subjected for CLP procedures underwent a small midline (1.5 cm) laparotomy to expose cecum. Fifty percent of the cecum was ligated with a 4-0 silk tie and punctured once with a 22-gauge needle. The abdomen was sutured in two layers with 4-0 suture for the peritoneum and abdominal musculature and wound clips for the skin. As described in the results, CLP was performed to induce polymicrobial sepsis in mice. The sham group underwent the same procedure, but without cecal ligation and puncture. Mice were randomized with regard to age and genotype.

H&E staining

During mouse autopsy, dissected mouse tissues were harvested freshly and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h. The fixed tissues were then embedded into paraffin, and sectioned at 5-μm thickness with a Microtome (Leica RM2016, Germany). Deparaffinized, rehydrated sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, and then differentiated in 0.1% acid alcohol followed by bluing and counterstaining in 0.5% eosin Y solution and the final dehydration. H&E stained sections were examined by a skilled pathologist.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Means between groups were calculated by Student's t-test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bo Zhang for TALEN vectors, K Newton and VM Dixit for Rip3−/− mice. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program; 2009CB522201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91029304, 30830092, 30921005, 81061160512), the Hi-Tech Research and Development Program of China (863 program; 2012AA02A201), the 111 Project (B12001), and the Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Cellular Stress Biology, Xiamen University (SKLCSB2012KF003).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Different deletions found in Mlkl mutant mice.

Expression of Rip3 and histomorphology of WT, Mlkl−/− and Rip3−/− mice.

Rip3 is not involved in activation of NF-κB and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs).

References

- Laster SM, Wood JG, Gooding LR. Tumor necrosis factor can induce both apoptic and necrotic forms of cell lysis. J Immunol. 1988;141:2629–2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Shimizu S, Watanabe T, et al. Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature. 2005;434:652–658. doi: 10.1038/nature03317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Purcell NH, et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature. 2005;434:658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature03434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Shen HM. To die or to live: the dual role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in autophagy and necrosis under oxidative stress and DNA damage. Autophagy. 2009;5:273–276. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Wang Y. Novel Ser/Thr protein phosphatases in cell death regulation. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27:43–52. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00034.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhong CQ, Zhang DW. Programmed necrosis: backup to and competitor with apoptosis in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1143–1149. doi: 10.1038/ni.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Yang Y, Mei Y, et al. Cleavage of RIP3 inactivates its caspase-independent apoptosis pathway by removal of kinase domain. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2056–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'en IL, Tsau JS, Molkentin JD, Komatsu M, Hedrick SM. Mechanisms of necroptosis in T cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:633–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin M, Anderton H, Voss AK, et al. IAPs limit activation of RIP kinases by TNF receptor 1 during development. EMBO J. 2012;31:1679–1691. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi J, Christofferson DE, Ng A, et al. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell. 2008;135:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprez L, Takahashi N, Van Hauwermeiren F, et al. RIP kinase-dependent necrosis drives lethal systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Immunity. 2011;35:908–918. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Zhang Y, Bai G, Li H. Necrostatin-1 ameliorates symptoms in R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e115. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkermann A, Brasen JH, De Zen F, et al. Dichotomy between RIP1- and RIP3-mediated necroptosis in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced shock. Mol Med. 2012;18:577–586. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Han V, Han J. New components of the necroptotic pathway. Protein Cell. 2012;3:811–817. doi: 10.1007/s13238-012-2083-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Necrosis, a well-orchestrated form of cell demise: signalling cascades, important mediators and concomitant immune response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1371–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golstein P, Kroemer G. Cell death by necrosis: towards a molecular definition. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach D, Kang TB, Kovalenko A. The extrinsic cell death pathway and the elan mortel. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1533–1541. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, et al. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DW, Shao J, Lin J, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Wang L, Miao L, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20054–20059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116302108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunai ZA, Imre G, Barna G, et al. Staurosporine induces necroptotic cell death under caspase-compromised conditions in U937 cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Li H, Yang M, et al. A role of RIP3-mediated macrophage necrosis in atherosclerosis development. Cell Rep. 2013;3:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorde-Khvalevsky E, Abramovitch R, Barash H, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 signaling attenuates liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2009;50:198–206. doi: 10.1002/hep.22973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichonas G, Murakami Y, Thanos A, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinases mediate retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor necrosis and compensate for inhibition of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21695–21700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009179107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Li G, Lan X, et al. Receptor interacting protein 3 suppresses vascular smooth muscle cell growth by inhibition of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt axis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9535–9544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther C, Martini E, Wittkopf N, et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature10400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148:213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, McQuade T, Siemer AB, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012;150:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan N, Lee IH, Borenstein R, et al. The NAD-dependent deacetylase SIRT2 is required for programmed necrosis. Nature. 2012;492:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nature11700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Jiang H, Chen S, Du F, Wang X. The mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 functions at the convergence point of multiple necrotic death pathways. Cell. 2012;148:228–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Jitkaew S, Cai Z, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5322–5327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200012109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DF, Tan W, Lillico SG, et al. Efficient TALEN-mediated gene knockout in livestock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17382–17387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211446109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF. TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science. 2011;333:1843–1846. doi: 10.1126/science.1204094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Freyvert Y, et al. Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases. Science. 2009;325:433. doi: 10.1126/science.1172447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashimo T, Takizawa A, Voigt B, et al. Generation of knockout rats with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) using zinc-finger nucleases. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbery ID, Ji D, Harrington A, et al. Targeted genome modification in mice using zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics. 2010;186:451–459. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.117002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DW, Zheng M, Zhao J, et al. Multiple death pathways in TNF-treated fibroblasts: RIP3- and RIP1-dependent and independent routes. Cell Res. 2011;21:368–371. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welz PS, Wullaert A, Vlantis K, et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2011;477:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1464-1469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro da Silva F, Nizet V. Cell death during sepsis: integration of disintegration in the inflammatory response to overwhelming infection. Apoptosis. 2009;14:509–521. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo KA, Johnson GL. Mixed-lineage kinase control of JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrm906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Different deletions found in Mlkl mutant mice.

Expression of Rip3 and histomorphology of WT, Mlkl−/− and Rip3−/− mice.

Rip3 is not involved in activation of NF-κB and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs).