Abstract

The recently identified TMEM16/anoctamin protein family includes Ca2+-activated anion channels (TMEM16A, TMEM16B), a cation channel (TMEM16F) and proteins with unclear function. TMEM16 channels consist of eight putative transmembrane domains (TMs) with TM5–TM6 flanking a re-entrant loop thought to form the pore. In TMEM16A this region has also been suggested to contain residues involved in Ca2+ binding. The role of the putative pore-loop of TMEM16 channels was investigated using a chimeric approach. Heterologous expression of either TMEM16A or TMEM16B resulted in whole-cell anion currents with very similar conduction properties but distinct kinetics and degrees of sensitivity to Ca2+. Furthermore, whole-cell currents mediated by TMEM16A channels were ∼six times larger than TMEM16B-mediated currents. Replacement of the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A with that of TMEM16B (TMEM16A-B channels) reduced the currents by ∼six-fold, while the opposite modification (TMEM16B-A channels) produced a ∼six-fold increase in the currents. Unexpectedly, these changes were not secondary to variations in channel gating by Ca2+ or voltage, nor were they due to changes in single-channel conductance. Instead, they depended on the number of functional channels present on the plasma membrane. Generation of additional, smaller chimeras within the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B led to the identification of a region containing a non-canonical trafficking motif. Chimeras composed of the putative pore-loop of TMEM16F transplanted into the TMEM16A protein scaffold did not conduct anions or cations. These data suggest that the putative pore-loop does not form a complete, transferable pore domain. Furthermore, our data reveal an unexpected role for the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels in the control of the whole-cell Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance.

Key points

The recently identified TMEM16/anoctamin protein family includes Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (TMEM16A and TMEM16B), a Ca2+-activated non-selective cation channel (TMEM16F) and proteins for which the function remains unclear.

TMEM16 channel proteins consist of eight putative transmembrane domains (TMs) with the 5th and 6th TMs flanking a loop predicted to protrude deep into the membrane. Recent studies suggest that this re-entrant loop may compose part of the pore of TMEM16A channels while also containing residues involved in Ca2+ binding.

Here, we investigate the functional role of the putative pore-loop by examining the electrophysiological properties of chimeras produced by transplanting this region between TMEM16 family members with different conduction properties and Ca2+ sensitivities.

We revealed that the putative pore-loop of TMEM16 channels has an unexpected role in controlling the whole-cell Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance by regulating the number of functional channels present on the plasma membrane.

Introduction

Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (CaCCs) play key roles in a plethora of cellular functions. Cl− currents activated by Ca2+ were observed for the first time about three decades ago in Xenopus oocytes (Barish, 1983; Miledi, 1982), in the inner segment of the photoreceptor (Bader et al. 1982) and in lachrymal acinar cells (Marty et al. 1984). Since these early observations, CaCC currents have been detected in several other cell types of both animal and plant species. CaCCs are involved in processes as diverse as epithelial secretion, nociception, fertilisation and regulation of smooth muscle tone (Jentsch et al. 2002; Nilius & Droogmans, 2003; Hartzell et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2012a). CaCCs are regulated by changes in both the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and the membrane potential; they therefore provide a link between Ca2+ signalling and cell electrical activity. Furthermore, expression of functional CaCCs on the plasma membrane, which modulates the whole-cell CaCC conductance, is regulated by chemical factors such as interleukins (Galietta et al. 2002) and cholesterol (Sones et al. 2010). There are also cell mechanisms that result in a non-uniform distribution of CaCCs on the cell surface (French et al. 2010).

The genes encoding CaCCs were only recently identified as the TMEM16/anoctamin family (Caputo et al. 2008; Schroeder et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2008). This gene family is composed of ten members. The electrophysiological properties of heterologously expressed TMEM16A/anoctamin1, or of the closely related TMEM16B/anoctamin2, directly resemble those of native CaCCs in terms of sensitivity to intracellular Ca2+, extent of outward rectification, ion selectivity and sensitivity to pharmacological agents (Flores et al. 2009; Duran & Hartzell, 2011; Kunzelmann et al. 2011b; Scudieri et al. 2011; Huang et al. 2012a). It is unclear whether other members of the TMEM16/anoctamin family form CaCCs (Galietta, 2009; Duran & Hartzell, 2011; Kunzelmann et al. 2011b; Scudieri et al. 2011). Furthermore, different TMEM16A splice variants give rise to channels with unique biophysical properties (Caputo et al. 2008; Ferrera et al. 2009). Studies involving knock-out mice or RNA silencing technology have provided further evidence that TMEM16A and TMEM16B are essential components of CaCCs in several cell types (Rock et al. 2009; Manoury et al. 2010; Billig et al. 2011; Thomas-Gatewood et al. 2011).

The membrane topology of TMEM16 proteins predicted from hydropathy analysis consists of eight TMs with intracellular N- and C-termini (Caputo et al. 2008; Schroeder et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2008; Kunzelmann et al. 2011a; Yu et al. 2012). Importantly, the topology involving eight TMs has been experimentally confirmed for TMEM16G/anoctamin7 (Das et al. 2008). So far, only a limited number of studies on the structure–function relationship of TMEM16 channels have been reported. The voltage-sensing region of some types of voltage-gated channels, such as voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels, was first identified to be a series of basic residues (arginines or lysines) within the ‘S4’ domain following analysis of their primary structure (Hille, 2001). In contrast, the sequence of TMEM16A and TMEM16B do not present equivalent putative voltage-sensing regions. However, a series of four/five glutamic acids in the first intracellular loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B appear to contribute to the voltage sensitivity of the channel (Xiao et al. 2011; Cenedese et al. 2012).

The location of the Ca2+ binding site in TMEM16A channels also remains elusive. A series of four residues (EAVK) in the first intracellular loop, however, appear to contribute to the Ca2+ sensitivity of TMEM16A (Xiao et al. 2011). Other studies have suggested that the N-terminus may participate in Ca2+ binding, directly or via the binding of calmodulin at this site (Ferrera et al. 2009; Tian et al. 2011). Recently, the region between TM5 and TM6 of TMEM16A was proposed to bear a Ca2+ binding site (Yu et al. 2012). Thus, the domains of the channel involved in Ca2+ binding and the transduction of Ca2+ binding into channel opening may be formed by residues that are distant from each other in the primary structure. Furthermore, the involvement of an auxiliary subunit cannot be ruled out.

The region between the TM5 and TM6 of TMEM16A is predicted to be a re-entrant domain. Notably, re-entrant loops are common features of ion channel pores. Furthermore, mutations in this region (R621E, K645E and K668E) have been reported to alter the ion selectivity of TMEM16A (Yang et al. 2008). Interestingly, a recent study from the Hartzell group challenged the view that this region forms a re-entrant loop protruding into the membrane from the extracellular side, and instead proposed an ‘inverted topology’ (Fig. 1B in Yu et al. 2012). According to this model the putative pore-loop would present a segment that is exposed to the intracellular environment (Yu et al. 2012).

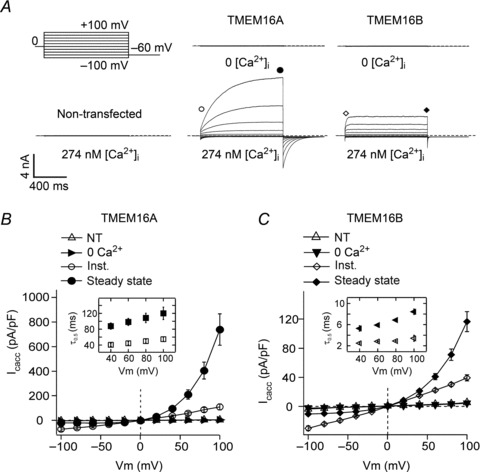

Figure 1. Whole-cell TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents.

A, whole-cell currents recorded from a non-transfected HEK-293T cell or HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16A or TMEM16B in the presence of 0 or 274 nm[Ca2+]i, as indicated. Dashed horizontal lines represent the zero-current level. Voltage protocol is shown in the upper left panel. B, mean whole-cell current density versus voltage relationships measured at the beginning (Inst.) or at the end (Steady state) of 1 s voltage pulses from −100 to +100 mV in 20 mV increments for HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16A in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i (n= 7). Mean whole-cell currents obtained from non-transfected (NT) HEK-293T cells ([Ca2+]i= 274 nm) (n= 5), and from transfected cells in 0 [Ca2+]i (n= 5) were measured only at the end of the pulse. C, mean whole-cell current density versus voltage relationships for TMEM16B (n= 8). Experimental conditions as described in B. Insets in B and C show mean τ0.5 of current activation (filled symbols) and deactivation (open symbols) for TMEM16A and TMEM16B, measured in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i at various membrane potentials (n= 7–8).

To summarise, the putative pore-loop may contribute to the permeation pathway in addition to containing residues involved in Ca2+ binding. This study aims to further our knowledge of the functional properties of the putative pore-loop by constructing chimeras involving TMEM16A and other TMEM16 proteins. The chimeric strategy using homologous, but functionally dissimilar, proteins has been used extensively to identify primary sequence elements associated with particular functions. TMEM16A and TMEM16B were chosen for this study as they reportedly function as CaCCs but have contrasting electrophysiological properties, including Ca2+ sensitivity (Flores et al. 2009; Duran & Hartzell, 2011; Kunzelmann et al. 2011b; Scudieri et al. 2011; Huang et al. 2012a). TMEM16F was also used because it has been reported to be selective for cations, albeit with a smaller unitary conductance than the one presented by TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels for anions (Yang et al. 2012). For this reason TMEM16F has been termed as a small-conductance Ca2+-activated non-selective cation channel (SCAN) (Yang et al. 2012). The degree of homology between TMEM16B and TMEM16F proteins with TMEM16A within the putative pore-loop is 68% and 48%, respectively.

The initial aim of this study was to determine the contribution of the putative pore-loop to the Ca2+ sensitivity and ion conduction properties of TMEM16 channels. Unexpectedly, we discovered that the ‘pore’ of TMEM16 channels has an additional role in that it regulates the number of channels present on the plasma membrane. Thus, the putative pore-loop of TMEM16 channels is a functionally critical region that integrates diverse roles of these Ca2+- and voltage-operated channels.

Methods

Details of the cell culture and patch-clamp recordings are provided in the Supplemental material, which is available online.

Molecular biology and cell transfection

Mouse TMEM16A (Genbank NM_178642), TMEM16B (NM_153589.2) and TMEM16F (NM_175344), each subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector were used in this study. TMEM16 chimeras were constructed using a PCR mutagenesis strategy for sequence swapping between related genes (Kirsch & Joly, 1998). HA-tags were inserted in the putative extracellular loops of TMEM16 proteins using inverse PCR mutagenesis (Gama & Breitwieser, 1999).

Electrophysiology

Composition of solutions

For the measurement of anion currents, the extracellular solution contained (mm): 150 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 d-mannitol and 10 Hepes; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The intracellular solution contained (mm): 130 CsCl, 10 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes and 8.0 mm CaCl2 to obtain approximately 274 nm free [Ca2+], pH was adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH. For intracellular solutions with higher [Ca2+]i, EGTA was replaced with equimolar HEDTA and 2.1, 3.1, 4.8, 7.8 or 9 mm CaCl2 were used to obtain approximately 605, 1040, 2270, 12460 and 78070 nm free [Ca2+], respectively (calculated with Patcher's Power tool, Dr Francisco Mendez and Frank Würriehausen, Max-Planck-Institut für biophysikalische Chemie, Göttingen, Germany). In anion selectivity experiments, the extracellular solution was composed of (mm): 150 NaX, 0.1 CaCl2, 10 glucose and 10 Hepes, where X = Cl−, SCN−, NO3−, I−, ClO4−, N3− or gluconate; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH and osmolality was adjusted to 320 mosmol kg−1 with d-mannitol. Liquid junction potentials were calculated (Barry & Lynch, 1991; Neher, 1992) and corrected off-line. To measure SCAN currents the extracellular solution contained (mm): 140 NaMes, 10 HEDTA, and 10 Hepes, pH was adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH and the intracellular solution contained (mm): 140 NaMes, 10 HEDTA, 10 Hepes and 9.72 CaCl2, providing a free [Ca2+]i of 100 μm, pH was adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH.

Stimulation protocols

Currents were recorded from transfected human embryonic kidney-293T (HEK-293T) cells using the whole-cell or inside-out configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Current versus voltage relationships were constructed by measuring the current at the beginning (instantaneous) or at the end (steady state) of 1 s voltage steps from −100 mV to +100 mV in 20 mV increments. The time interval between the beginnings of subsequent voltage steps was 3 s. The holding potential was 0 mV. Membrane current densities were calculated by dividing the current by the cell capacitance.

The voltage dependencies of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels were determined by constructing conductance (G) versus voltage relationships in the presence of various [Ca2+]i. A 1 s pre-pulse applied to different membrane potentials (from −100 to +180 mV in 40 mV increments) was followed by a 0.5 s tail pulse to −60 mV. Tail currents at each potential were fitted with a single exponential function. The instantaneous tail current amplitude was estimated from extrapolation of the fit to the beginning of the test pulse and G calculated as G=I/(Vm–ECl). Normalised G (G/Gmax) was plotted against the voltage of the pre-pulse. Under these conditions, the amplitude of the G/Gmax is directly proportional to the open probability (Po) of the channel at the pre-pulse voltage (Bezanilla, 2000; Tammaro et al. 2005). The constructed relationships were fitted with the Boltzmann equation of the form:

| (1) |

where z is the number of gating charges moving through the entire applied field during channel activation, V0.5 is the voltage at which the G is half-maximal and is associated with the conformational energy required for the channel to open, F is Faraday's constant, R is the universal gas constant and T is the absolute temperature.

Relative anion permeabilities of TMEM16A and TMEM16B were assessed by determining the shift in reversal potential (Erev) of the currents when extracellular Cl− (154 mm) was replaced with an equimolar concentration of other monovalent anions (X). The permeability ratio was estimated using the following equation (Hille, 2001):

| (2) |

where ΔErev represents the difference of the Erev for the anion X relative to the ECl. To determine the Erev in the presence of different anions, tail current versus voltage relationships were constructed by measuring the tail current amplitude (It) at each voltage (from −60 mV to +60 mV in 10 mV increments; pulse duration 0.5 s) after a 1 s depolarising step to +70 mV, elicited every 3 s from a holding potential of 0 mV. The It values at each voltage were determined from a single exponential fit of the current as describe above. The It values were plotted as a function of the membrane potential. The relative chord conductance was measured between an interval of ±25 mV around the Erev.

The [Ca2+]i–response relationships were fitted with the Hill–Langmuir equation of the form:

| (3) |

where I is the current measured at a given [Ca2+]i, Imax is the current measured at the highest [Ca2+]i, EC50 is the [Ca2+]i that causes half-maximal current activation and h is the slope factor (Hill coefficient).

For non-stationary noise analysis (Heinemann & Conti, 1992; Tammaro & Ashcroft, 2007) 50–200 identical pulses to a test potential of +70 mV (filtered at 10 kHz and sampled at 50 kHz) were applied and the mean response, I, was calculated. The variance, σ2, was computed from the average squared difference of consecutive traces. Background variance at 0 mV was subtracted and the variance–mean plot was fitted by:

| (4) |

with the single channel current, i, and the number of channels, N, as free parameters. In these experiments only cells presenting whole-cell currents of amplitude lower than ∼3.5 nA were used.

Data analysis

Data were analysed with self-written routines developed in the IgorPro (Wavemetrics, OR, USA) environment or using Ana (http://users.ge.ibf.cnr.it/pusch/programs-mik.htm). Student's two-tailed t test or ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test were used for statistical analysis as appropriate and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are given as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) along with the number of experiments (n).

Immunocytochemistry

To visualise and quantify the presence of various TMEM16 proteins on the plasma membrane, immunocytochemistry experiments were performed on transiently transfected HEK-293T cells. Permeabilised or non-permeabilised conditions were used to detect either total cell protein or proteins expressed on the plasma membrane, respectively (Burgess et al. 2010; Gavet & Pines, 2010; Potapova et al. 2011). Experiments were conducted at +4°C 48 h after transfection, unless otherwise stated. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 2.5 μg ml−1 anti-HA tag antibody (Abcam; ab9110) in PBS (1 h). Cells were then fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (15 min) and free aldehydes neutralised with 0.1 m glycine (10 min). Primary antibodies were visualised with 2 μg ml−1 Alexa 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Invitrogen; 1 h, room temperature). For detection of intracellular epitopes, after fixation cells were blocked and permeabilised with 4% donkey serum and 0.1% saponin, respectively (1 h, room temperature). Cells were incubated with 2.5 μg ml−1 anti-HA tag antibodies (Abcam; ab9110) in the presence of 4% donkey serum and 0.1% saponin in PBS (3 h, room temperature). Primary antibodies were detected with 2 μg ml−1 Alexa 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibodies in PBS with 4% donkey serum (1 h, room temperature). Images were collected on the Olympus BX51 upright microscope maintaining identical settings and analysed using ImageJ software. The fraction of TMEM16 proteins expressed on the plasma membrane was expressed as the ratio of the average fluorescence measured from at least 35 cells in non-permeabilised and permeabilised conditions.

Results

Comparison of the electrophysiological properties of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels

A side by side comparison of the TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents recorded using the patch-clamp technique has never been reported. This study began by directly comparing the capacity of heterologously expressed TMEM16A and TMEM16B to mediate Ca2+-activated Cl− currents, using the whole-cell and inside-out patch-clamp techniques in transfected HEK-293T cells.

Whole-cell current magnitudes

Figure 1A shows that in the absence of intracellular Ca2+ the currents recorded from cells transfected with TMEM16A or TMEM16B were indistinguishable from the very small currents observed in non-transfected cells over a wide range of membrane potentials. When cells were dialysed with an intracellular solution containing [Ca2+]i (274 nm), hyperpolarising or depolarising steps elicited instantaneous TMEM16A or TMEM16B currents, followed by time-dependent relaxations towards new steady-state levels. For TMEM16A and TMEM16B the average instantaneous current versus voltage relationships were linear, but the relationship between steady-state current, measured at the end of a 1 s voltage step and the voltage, was outwardly rectifying (Fig. 1B and C). The steady-state currents at negative potentials were smaller while those at positive potentials were larger than the instantaneous currents. In agreement with previous reports (Xiao et al. 2011; Cenedese et al. 2012), the extent of outward rectification of TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents appeared to diminish as [Ca2+]i was raised (Supplemental Fig. 1, available online). Although outward rectification was observed for both TMEM16A and TMEM16B, the magnitude of the time-dependent current component at each voltage differed between the two channels. Expressing this phenomenon as the ratio between the steady-state current and the instantaneous current at +100 mV (Iss/IInst), gives a fraction of 5.4 ± 0.8 (n= 7) for TMEM16A and 3.0 ± 0.1 (n= 8) for TMEM16B (P < 0.05).

An electrophysiological parameter that clearly differed between TMEM16A and TMEM16B was the current density. In the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i, whole-cell currents generated by TMEM16A at +100 mV were approximately six times larger (739 ± 127 nA pF-1; n= 7) than currents mediated by TMEM16B (116 ± 14 nA pF-1; n= 8) (Fig. 1B and C).

Kinetics of the currents

Figure 1 suggests that the rate of current activation differs between TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents. The time-course of the rise in current was quantified as the time required to reach the half-maximal current (τ0.5). As the voltage increased, τ0.5 also slightly increased, equalling 88 ± 8 ms (n= 7) at +40 mV and 120 ± 16 ms (n= 7) at +100 mV for TMEM16A channels (Fig. 1B, inset) (P < 0.05). TMEM16B currents activated ∼15 times more rapidly than TMEM16A currents: τ0.5 was 5.3 ± 0.5 ms (n= 8) at +40 mV and 8.4 ± 0.5 ms (n= 8) at +100 mV (Fig. 1C, inset) (P < 0.05). The tail currents measured upon repolarisation to −60 mV were quantified in the same way. For both channels, τ0.5 did not show a significant change with voltage over the range of +40 mV to +100 mV (insets in Fig. 1B and C). The τ0.5 for the deactivating tail current was 41 ± 4 ms (n= 7, TMEM16A) and 2.5 ± 0.1 ms (n= 8, TMEM16B) when preceded by a pre-pulse to +40 mV and 55 ± 5 (n= 7, TMEM16A) and 3.4 ± 0.6 (n= 8, TMEM16B) when preceded by a pre-pulse to +100 mV. Thus, the time necessary to respond to depolarisation or hyperpolarisation differed between TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels by more than one order of magnitude.

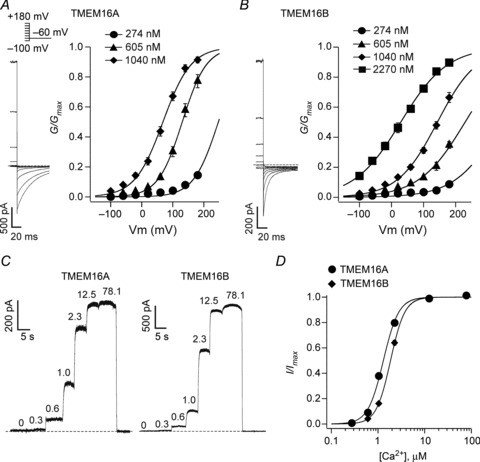

Voltage sensitivity

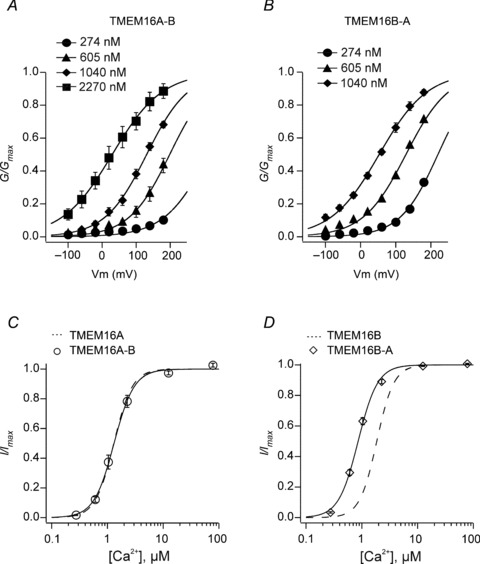

The voltage dependence of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels was studied in more detail by constructing conductance versus voltage relationships at various [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2A and B). These curves provide a measure of the change in channel Po as a function of the voltage. The values of V0.5 for TMEM16A channels were ∼75–100 mV smaller than those obtained for TMEM16B channels at various [Ca2+]i. V0.5 progressively shifted to lesser values as the [Ca2+]i was increased from 274 nm to 2.27 μm. Specifically, for both channels, V0.5 values were reduced by 180–200 mV as [Ca2+]i was increased to ∼1 μm. For TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels, the values of z did not change as [Ca2+]i was varied (Table 1).

Figure 2. Voltage and Ca2+-sensitivity of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels.

A, left panel: tail currents recorded from an inside-out patch excised from a HEK-293T cell expressing TMEM16A, in the presence of 605 nm[Ca2+]i. Stimulation protocol shown above. Horizontal dashed line indicates the zero-current level. Right panel: mean normalised TMEM16A conductance versus voltage relationships obtained in the presence of 274, 605 or 1040 nm[Ca2+]i, as indicated (n= 9). B, left panel: tail currents recorded from an inside-out patch excised from an HEK-293T cell expressing TMEM16B in the presence of 605 nm[Ca2+]i in response to the stimulation protocol shown in A. Horizontal dashed line indicates the zero-current level. Right panel: mean normalised TMEM16B conductance versus voltage relationships obtained in the presence of 274, 605, 1040 or 2270 nm[Ca2+]i, as indicated (n= 7). The smooth curves in A and B are the best fits of the data using eqn. (1). C, currents recorded from inside-out patches excised from HEK-293T cell expressing TMEM16A or TMEM16B in response to various [Ca2+]i (μm), as indicated. The voltage was maintained at +70 mV for the whole duration of the recordings. D, mean relationships between [Ca2+]i and the current measured at +70 mV and normalised to the maximal response for TMEM16A (n= 5) and TMEM16B (n= 6). The smooth curves are the best fits of the data using eqn. (3).

Table 1.

Parameters (V0.5 and z) obtained from the Boltzmann fit of TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A conductance versus voltage relationships at various [Ca2+]i

| [Ca2+]i (nm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 274 | 605 | 1040 | 2270 | ||

| TMEM16A | V0.5 (mV) | 247 ± 6† | 131 ± 7† | 67 ± 6† | N/A |

| (n= 7) | (n= 9) | (n= 9) | |||

| z | 1.7 ± 0.2† | 1.4 ± 0.1† | 1.9 ± 0.1† | N/A | |

| (n= 7) | (n= 9) | (n= 9) | |||

| TMEM16B | V0.5 (mV) | 343 ± 12 | 205 ± 16 | 121 ± 12 | 15 ± 9 |

| (n= 7)* | (n= 7)* | (n= 6)* | (n= 6) | ||

| z | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | |

| (n= 7)* | (n= 6)* | (n= 6)* | (n= 6) | ||

| TMEM16A-B | V0.5 (mV) | 313 ± 18 | 196 ± 21 | 133 ± 15 | 30 ± 17 |

| (n= 5)* | (n= 5)* | (n= 5)* | (n= 5) | ||

| z | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | |

| (n= 5)* | (n= 5)* | (n= 5) | (n= 5) | ||

| TMEM16B-A | V0.5 (mV) | 222 ± 7 | 129 ± 2 | 53 ± 7 | N/A |

| (n= 5) † | (n= 5) † | (n= 5) † | |||

| z | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | N/A | |

| (n= 5)* | (n= 5)* | (n= 5)* | |||

and † indicate statistically significant difference from TMEM16A and TMEM16B, respectively.

Ca2+ sensitivity

To analyse the Ca2+ sensitivity of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels, [Ca2+]i–response relationships were constructed by measuring currents at a constant potential while varying [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2C and D). Table 2 reports the parameters (EC50 and h) obtained from the fit of these relationships with eqn. (3). The slope factor h was very similar for TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels (∼2.7–2.8). In contrast, the EC50 differed by ∼40%, with TMEM16A channels being more sensitive to Ca2+ than TMEM16B channels.

Table 2.

Parameters (EC50 and h) obtained from the Hill–Langmuir fit of TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A [Ca2+]i– response relationships

| TMEM16A | TMEM16A-B | TMEM16B | TMEM16B-A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μm) | 1302 ± 33† | 1304 ± 69† | 1860 ± 53* | 881 ± 40*,† |

| (n= 5) | (n= 6) | (n= 6) | (n= 6) | |

| h | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| (n= 5) | (n= 6) | (n= 6) | (n= 6) |

and † indicate statistically significant difference from TMEM16A and TMEM16B, respectively.

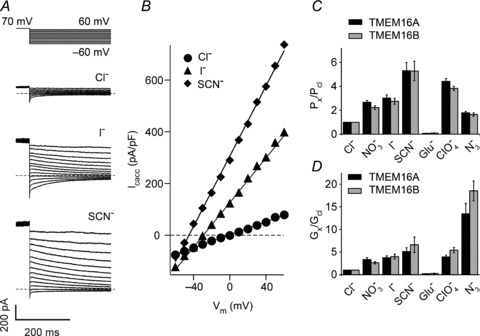

Conduction properties

Non-stationary noise analysis was used to determine the single-channel current (i) of TMEM16A and TMEM16B (Fig. 3). The average i was assessed from the fit with eqn. (4) of the relationship between the mean current and the variance around the mean. For TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels i was 0.25 ± 0.02 (n= 5) and 0.32 ± 0.03 pA (n= 8), respectively. This corresponds to a single channel conductance of 3.5 ± 0.3 and 3.9 ± 0.1 pS for TMEM16A and TMEM16B, respectively. N was estimated to be 402,119 ± 103,017 (n= 5) and 93,495 ± 20,247 (n= 8) for TMEM16A and TMEM16B, respectively. The relative anion permeability and conductance of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels were also determined. Figure 4A and B shows typical current versus voltage relationships recorded in the presence of extracellular Cl−, I− or SCN−. Figure 4C reports the selectivity sequence of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels for several anions, while Fig. 4D shows the mean chord conductance for the same anions. No significant difference was seen between TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels in either of these properties. The relative order of selectivity (Px/PCl) for TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels was SCN− > ClO4− > I− > NO3− > N3− > Cl−≫ gluconate. The relative conductance (Gx/GCl) sequence for both channels was: N3− > SCN− > I− > NO3− > ClO4− > Cl−≫ gluconate.

Figure 3. Non-stationary noise analysis for whole-cell TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents.

Whole-cell currents were recorded from HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16A or TMEM16B channels. A, mean TMEM16A current and variance around the mean obtained from 165 current traces recorded in response to 1.5 s pulses to +70 mV followed by 1 s repolarizations to −60 mV in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i. Horizontal dashed lines represent the zero-current or zero-variance level. B, current variance plotted against the mean current for the experiment shown in A. The parabolic line is the best of the data using eqn (4). The single-channel current, i, calculated from the fit was 0.24 pA. C, mean TMEM16B current and variance around the mean obtained from 200 current traces recorded in response to the stimulation protocol described in A. Horizontal dashed lines represent the zero-current or zero-variance level. D, current variance plotted against the mean current for the experiment shown in C. The parabolic line is the best of the data using eqn (4). The single-channel current, i, calculated from the fit was 0.27 pA.

Figure 4. Permeability and selectivity of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels to a range of anions.

A, whole-cell currents recorded from a HEK-293T cell expressing TMEM16A in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i and different extracellular anions, as indicated. Dashed horizontal lines indicate zero-current levels. For the currents recorded in the presence of Cl− only traces every 20 mV are shown for clarity. The stimulation protocol is shown above. B, instantaneous currents (obtained from traces in A) plotted versus the voltage. C, mean relative anion selectivity (Px/PCl) for TMEM16A (n= 6–12) and TMEM16B (n= 6–9) channels. D, mean relative anion conductance (Gx/GCl) for TMEM16A (n= 6–12) and TMEM16B (n= 6–9) channels.

To summarise, the first set of experiments illustrate that TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels share a range of electrophysiological characteristics including the fact that, under the experimental conditions used: (i) Ca2+ is mandatory for TMEM16A and TMEM16B channel activity and (ii) both channels display the same degree of permeability to various anions. However, TMEM16A and TMEM16B also differ in a range of properties including: (i) the magnitude of the time-dependent current increase observed in response to depolarising voltage steps; (ii) the kinetics of activation and deactivation; (iii) the overall Ca2+- and voltage-sensitivity, and (iv) the magnitude of whole-cell currents (current density) they mediate.

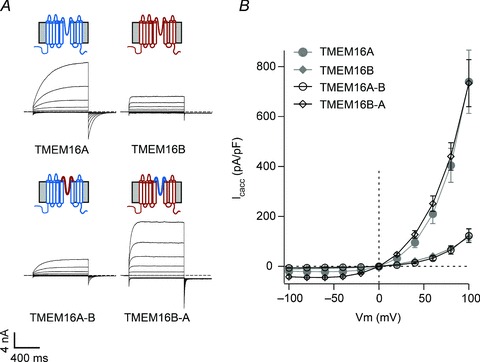

Effects of chimeric constructs involving the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B

To investigate the role of the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels, chimeric constructs were engineered in which the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A was substituted with that of TMEM16B (TMEM16A-B) and vice versa (TMEM16B-A). The exact regions transferred in these chimeras are listed in Supplemental Table 1. As with wild-type channels, in the absence of Ca2+ no currents were observed in the −100 to +100 mV range in cells expressing TMEM16A-B or TMEM16B-A channels (data not shown). When the [Ca2+]i was raised to 274 nm, prominent outwardly rectifying currents became apparent (Fig. 5A). At +100 mV, the current density for TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A channels was 123 ± 27 pA pF-1 (n= 7) and 734 ± 94 pA pF-1 (n= 8), respectively. The whole-cell current densities mediated by TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A were equal to those mediated by TMEM16B and TMEM16A channels, respectively (Fig. 5B). Thus, the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels appears to control the magnitude of the current density.

Figure 5. Whole-cell currents for wild-type and chimeric TMEM16 channels.

A, whole-cell currents recorded from HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B or TMEM16B-A, as indicated. Currents were elicited by 1 s voltage pulses from −100 to +100 mV in 20 mV increments followed by 0.5 s steps to −60 mV in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i. Dashed horizontal lines represent the zero-current level. Diagrams above electrophysiological traces are schematic illustrations of the membrane topology of TMEM16 channels (wild-type, chimeras). TMEM16A and TMEM16B are represented in blue and red, respectively. B, mean whole-cell current density versus voltage relationships for TMEM16A (n= 7), TMEM16B (n= 8), TMEM16A-B (n= 7) and TMEM16B-A (n= 8). Data for TMEM16A and TMEM16B are re-plotted from Fig. 1.

Visual inspection of Fig. 5A suggested that the kinetics of wild-type and chimeric channel currents in response to depolarising voltage steps is variable. We therefore quantitatively compared the electrophysiological properties of wild-type and chimeric whole-cell currents elicited by depolarising pulses to +100 mV followed by a 0.5 s hyperpolarisation to −60 mV (Fig. 6A). Parameters measured were Iss/IInst, the fraction (in %) of the small residual current at the end of the hyperpolarising (tail) pulse relative to the steady-state current at +100 mV (Itail/I100) and the τ0.5 of activation at +100 mV (Fig. 6B). Iss/IInst and Itail/I100 calculated for TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A channels were indistinguishable from those measured for TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels, respectively (Fig. 6). However, there were significant differences amongst the chimeras in their time-dependent gating kinetics. The TMEM16A-B channels presented a reduction in τ0.5 of about 50% (compared to TMEM16A channels). Conversely, TMEM16B-A channels presented an increase in τ0.5 by a factor ∼2 (compared to TMEM16B channels). Thus, the putative pore-loop region determines a significant component of the kinetic characteristics of these channels.

Figure 6. Current characteristics of wild-type and chimeric TMEM16 channels.

A, whole-cell currents recorded from HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B or TMEM16B-A, as indicated. Currents were elicited by a 1 s voltage pulse to +100 mV followed by a 0.5 s repolarisation to −60 mV in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i. Horizontal arrows and vertical punctuated lines indicate instantaneous currents and τ0.5 of activation, respectively. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the zero-current level. Currents have been normalised to allow visual comparison. B, mean Iss/IInst, Itail/I100 and τ0.5 of current activation at +100 mV for TMEM16A (n= 7), TMEM16B (n= 8), TMEM16A-B (n= 7) and TMEM16B-A (n= 8), as indicated. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05); ‘ns’ indicates that the difference between the two groups was not significant (P > 0.05).

The next series of experiments aimed to determine what caused the changes in whole-cell current density discussed above. A whole-cell macroscopic ionic current (I) is the product of:

| (5) |

where N is the number of functional channels present in the plasma membrane. Thus, differences in macroscopic current densities observed for wild-type and chimeric channels must be due to a change in at least one of the parameters of eqn. (5).

i– Single channel current

As mentioned above (Fig. 3) the single-channel currents of TMEM16A and TMEM16B are not statistically different. Thus, a change in i is unlikely to underlie the changes in current densities described in Fig. 5.

Po– Sensitivity of chimeric channels to voltage and Ca2+

To determine the Po of chimeric channels in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i (the concentration used in whole-cell experiments), the response of the channels to a range of [Ca2+]i and membrane potentials was determined as described in Methods and the current–voltage relationships fitted with eqn. (1). This analysis revealed that parameters z and V0.5 for TMEM16A-B were not statistically different from those relative to TMEM16B channel currents (Fig. 7A and Table 1). For TMEM16B-A, V0.5 values were not statistically different from those of TMEM16A channel currents, but the z parameters were very close to those measured for TMEM16B currents (Fig. 7B and Table 1). Importantly, there was no change in the fraction of TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A currents at potentials ≤100 mV in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i. This implies that the different current densities reported in Fig. 5 cannot be due to a differential response of wild-type and chimeric channels to voltage.

Figure 7. Ca2+-sensitivity of chimeric TMEM16 channels.

A, mean normalised TMEM16A-B conductance versus voltage relationships obtained in the presence of 274, 605, 1040 or 2270 nm[Ca2+]i, as indicated (n= 5). B, mean normalised TMEM16B-A conductance versus voltage relationships obtained in the presence of 274, 605 or 1040 nm[Ca2+]i, as indicated (n= 5). C, mean relationships between [Ca2+]i and inside-out TMEM16A-B currents normalised to the maximal response measured at +70 mV (n= 6). D, mean relationships between [Ca2+]i and inside-out TMEM16B-A currents normalised to the maximal response measured at +70 mV (n= 6). The smooth curves in C and D represent the best fits of the data using eqn (3). Dashed curves in C and D are the fits of the data for TMEM16A and TMEM16B, re-plotted from Fig. 2.

We next explored whether the chimeric channels display an altered Ca2+ sensitivity at a fixed membrane potential. Figure 7C indicates that the EC50 and h values measured for TMEM16A-B channel currents are indistinguishable from those observed for TMEM16A currents (see Table 2). In contrast, TMEM16B-A channels maintained the h value that was measured for TMEM16B channels, but the [Ca2+]i–response curve for TMEM16B-A channels was shifted to the left with the EC50 being reduced by ∼1 μm (Fig. 7D and Table 2). Importantly, at 274 nm[Ca2+]i there was no significant difference between the fraction of current observed for wild-type (TMEM16A and TMEM16B) and chimeric (TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A) channels, which in all cases was ∼2% of the maximum current observed at [Ca2+]i≥ 12.5 μm.

Thus, the differences in TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A channel current densities are not due to changes in Po because in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i all channels displayed a similar degree of sensitivity to both voltage and Ca2+. Taken together with the observation that TMEM16A and TMEM16B share a similar single-channel conductance, these data therefore suggest that the different current densities of TMEM16A, TMEM16B, TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A channels are determined by a distinct number of functional channels present on the plasma membrane (i.e. N).

N− The putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B as a regulator of channel trafficking

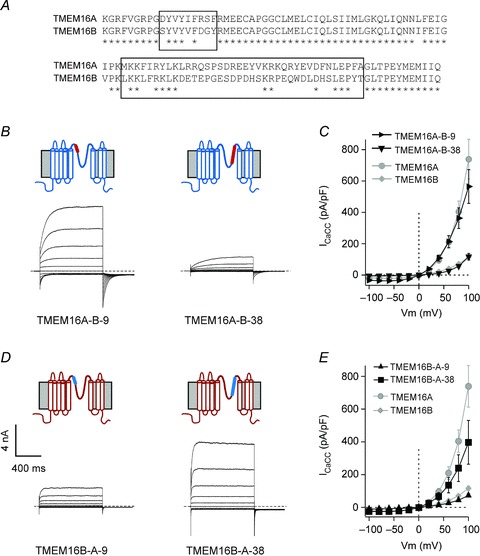

The fact that chimeric TMEM16A-B and TMEM16B-A channels gave rise to altered current density suggested that the putative pore-loop may contain a motif/s that controls channel trafficking. Analysis of the putative pore-loop sequence of TMEM16A and TMEM16B indicated that this region contains areas of complete sequence identity, while for two stretches of sequence the percentage of identity is only 32–44% (Fig. 8A). These are a region of 9 (608–616 in TMEM16A) and 38 (656–693 in TMEM16A) amino acids. Thus, we constructed chimeras where only these specific regions of 9 or 38 amino acids of TMEM16B were transferred into TMEM16A. We termed these chimeric constructs TMEM16A-B-9 and TMEM16A-B-38, respectively. Complementary chimeras obtained by transplanting the segment of 9 or 38 residues of TMEM16A into TMEM16B were termed TMEM16B-A-9 and TMEM16B-A-38, respectively.

Figure 8. Current-voltage relationship of additional chimeric TMEM16 channels.

A, sequence alignment of the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A (599–705) and TMEM16B (644–750) proteins. Asterisks indicate residues that are identical in the two channels. Boxes indicate the regions of nine and 38 residues that are substantially different between TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels. B, whole-cell currents recorded from HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16A-B-9 and TMEM16A-B-38 chimeric channels in response to the voltage protocol shown in Fig. 1A and in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i. Dashed horizontal lines represent the zero-current level. Diagrams above electrophysiological traces are schematic illustrations of the membrane topology of TMEM16A-B-9 and TMEM16A-B-38 chimeric channels. Segments of TMEM16A and TMEM16B are represented in blue and red, respectively. C, mean whole-cell current density versus voltage relationships for TMEM16A-B-9 (n= 5), TMEM16A-B-38 (n= 4), TMEM16A (n= 7) and TMEM16B (n= 8), as indicated. Data for TMEM16A and TMEM16B are re-plotted from Fig. 1. D, whole-cell currents recorded from HEK-293T cells expressing TMEM16B-A-9 and TMEM16B-A-38 chimeric channels in response to the voltage protocol shown in Fig. 1A and in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i. Dashed horizontal lines represent the zero-current level. Diagrams above electrophysiological traces are schematic illustrations of the membrane topology of TMEM16B-A-9 and TMEM16B-A-38 chimeric channels. Segments of TMEM16A and TMEM16B are represented in blue and red, respectively. E, mean whole-cell current density versus voltage relationships for TMEM16B-A-9 (n= 6), TMEM16B-A-38 (n= 5), TMEM16A (n= 7) and TMEM16B (n= 8), as indicated. Data for TMEM16A and TMEM16B are re-plotted from Fig. 1.

All four chimeric constructs gave rise to functional channels when transfected into HEK-293T cells (Fig. 8B–E). Figure 8C shows that in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i, TMEM16A-B-9 and TMEM16A-B-38 chimeras gave rise to a current of identical amplitude to those generated by TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels, respectively. In contrast, the current density associated with TMEM16B-A-9 and TMEM16B-A-38 chimeras (Fig. 8E) was not statistically different from the magnitude of currents mediated by TMEM16B and TMEM16A channels, respectively. Thus, this region of 38 amino acids within the putative pore-loop of TMEM16 channels contains elements that control the presence of functional channels on the plasma membrane that subsequently lead to changes in whole-cell current density.

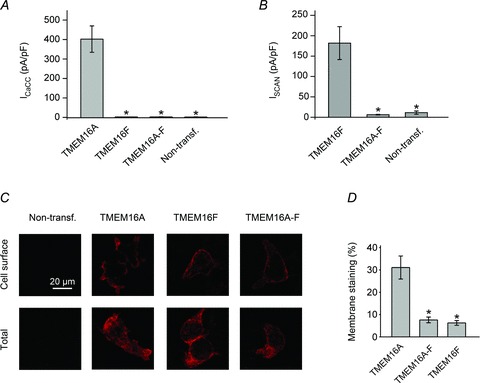

Expression of chimeras involving the putative pore-loop of TMEM16F

In a final series of experiments, the possibility that the putative pore-loop forms a complete, functional ionic conduction pathway was examined by engineering chimeric constructs in which the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A was substituted with the equivalent region of TMEM16F (TMEM16A-F). Figure 9A shows that, when expressed in HEK-293T cells, TMEM16A-F did not give rise to whole-cell CaCC currents at voltages as high as +80 mV.

Figure 9. Whole-cell current density and surface expression of TMEM16A, TMEM16F and TMEM16A-F channels.

A, mean whole-cell Cl− current density recorded from non-transfected HEK-293T cells and cells expressing TMEM16A, TMEM16F or TMEM16A-F measured at +80 mV in the presence of 274 nm[Ca2+]i (n= 5–7). B, mean whole-cell SCAN current density recorded from non-transfected HEK-293T cells and cells expressing TMEM16F or TMEM16A-F measured at +80 mV in the presence of ∼100 μm[Ca2+]i (n= 8–11). C, epifluorescence images of non-transfected HEK-293T cells or cells expressing HA-tagged TMEM16A, TMEM16F or TMEM16A-F, as indicated (see Supplemental material for details). Anti-HA antibodies were visualised with Alexa Fluor 596-labelled secondary antibodies (red) in non-permeabilised (Cell surface) or permeabilised (Total) conditions, as indicated. For each construct, images were acquired using identical acquisition settings. D, mean cell surface labelling expressed as a percentage of the total labelling for all HA-tagged constructs (n= 35–73; obtained using four consecutive cultures of transiently transfected HEK-293T cells). Asterisks indicate a significant difference to TMEM16A (P < 0.05).

Whole-cell recordings in the presence of 78.1 μm[Ca2+]i were also performed to test if the lack of TMEM16A-F mediated CaCC current may be due to impaired Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel. In the presence of 78.1 μm[Ca2+]i, the CaCC current density at +80 mV for TMEM16F and TMEM16A-F were 3.3 ± 0.8 pA pF-1 (n= 4) and 3.4 ± 1.0 pA pF-1 (n= 4), respectively (not significantly different from the current density in non-transfected cells, 3.8 ± 0.7 pA pF-1 (n= 5), data not shown).

We also asked if TMEM16A-F channels were able to conduct cations. Experiments were conducted in the absence of conducting anions and in the presence of 100 μm[Ca2+]i as previous studies indicated that TMEM16F SCAN currents are only active in the presence of high [Ca2+]i (Yang et al. 2012). Figure 9B demonstrates that TMEM16F mediated large SCAN currents (182 ± 40 pA pF-1 at +80 mV (n= 8)) under these conditions; however, currents mediated by TMEM16A-F (6.4 ± 0.9 pA pF-1 at +80 mV (n= 9)) were indistinguishable from those measured in non-transfected cells.

Another possible explanation for the lack of whole-cell CaCC or SCAN currents for TMEM16A-F chimeric channels is that they are not trafficked to the plasma membrane. Immunocytochemistry was performed to assess the surface expression of TMEM16A-F and TMEM16F compared to TMEM16A channels (Fig. 9C). New constructs were engineered in which a HA-tag was inserted in five different positions within the putative extracellular loops of TMEM16A (Supplemental Fig. 2). One position was identified that did not affect the current amplitude and was detectable in immunocytochemistry experiments (see Supplemental material). All chimeras were therefore tagged in this position. Figure 9C and D shows that ∼30% of TMEM16A channels in transfected HEK-293T cells were present on the plasma membrane. TMEM16F and TMEM16A-F were present on the plasma membrane, although to a lesser extent (6–8%). Thus, heterologously expressed TMEM16A-F proteins are trafficked to the plasma membrane but are unable to conduct anions or cations.

Discussion

The key finding of this paper is the observation that the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B has an unanticipated role in modulating the whole-cell CaCC conductance. This specific effect depends on the regulation of the number of functional channels present on the plasma membrane.

The putative pore-loop of TMEM16 channels as a regulator of channel trafficking

The trafficking of ion channels is controlled by a variety of factors, including association with auxiliary subunits, ubiquitin ligases and interactions with other membrane receptors (such as G protein-coupled receptors) (Schwappach, 2008; Simms & Zamponi, 2012). Several classes of specific amino acid motifs within membrane proteins have been identified that regulate the export/retention from/within the endoplasmic reticulum (Ma & Jan, 2002). For ion channels these motifs are usually present at the N- or C-termini (Ma & Jan, 2002; Schwappach, 2008; Simms & Zamponi, 2012). Here, we show that a region of 38 amino acids within the putative pore-loop of TMEM16 channels regulates the number of functional channels present on the plasma membrane. A role for the pore of an ion channel in the regulation of trafficking is not unprecedented. For example, pore residues of K+ channels participate in channel trafficking (Manganas et al. 2001; Zhu et al. 2005). The putative pore region sequence of TMEM16A and TMEM16B does not contain canonical trafficking motifs. The region of 38 amino acids that we have identified in the TMEM16A channel includes recognition sites for protein kinase C and casein kinase 2 that have been implicated in regulating ion channel trafficking, for example in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Luz et al. 2011). However, these sites appear to be conserved in TMEM16B. Thus, they cannot be responsible for the differential current density associated with the two channels. This suggests the presence of a non-canonical trafficking motif/s within the 38 amino acid stretch that we have identified. Our purely electrophysiological analysis, however, cannot define the exact subcellular processes underlying altered current densities. Possible explanations might involve changes in translation efficiency of channel proteins or their delivery to/retraction from the plasma membrane.

TMEM16A and TMEM16B share electrophysiological similarities

TMEM16A and TMEM16B are the two most closely related members of the TMEM16 family and have an overall sequence identity of ∼58%, with homology being higher within the putative transmembrane segments. These channels also share some electrophysiological characteristics. For both channels, the response to depolarising pulses consists of instantaneous currents followed by time-dependent current relaxations. The instantaneous current is mediated by channels that are open at the holding potential (Scudieri et al. 2011; Cenedese et al. 2012). Usually, the conductance of an open channel is almost constant at various voltages, except when the ionic concentrations at the two sides of the membrane are largely asymmetrical, or in cases of voltage-dependent block of the ion channel pore (Hille, 2001). Thus, the relationship between the instantaneous TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents and the voltage was linear (this study and Cenedese et al. 2012). The strong outward rectification of the steady-state current versus voltage relationship (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1) that we observed at [Ca2+]i < 1 μm is therefore the result of the modulation of the channel (TMEM16A or TMEM16B) Po by voltage (Ferrera et al. 2009; Cenedese et al. 2012).

The single-channel currents of TMEM16A and TMEM16B were not statistically different. Both TMEM16A and TMEM16B were permeable to various anions (Schroeder et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2008; Pifferi et al. 2009). The degree of permeability and conductance varied depending on the anion but the Px/PCl and Gx/GCl sequences were the same for both channels. The ion permeability is a measure of the ability of an ion to enter into the channel pore, while the conductance is an indication of the energy required for the ion to pass through the whole length of the pore (Lauger, 1973; Halm & Frizzell, 1992; Qu & Hartzell, 2000). Thus, the fact that Px/PCl and Gx/GCl sequences do not coincide indicates that the processes of the ion entering the channel pore and passing through it are unequally favourable. This may be the result of the ion binding within the pore. We demonstrated that TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels display indistinguishable Px/PCl and Gx/GCl sequences. This may suggest that the regions within the putative pore-loop that differ between TMEM16A and TMEM16B do not contribute to anion selectivity or conductance.

The putative pore-loop of TMEM16A and TMEM16B regulates the Ca2+- and voltage-sensitivity of the channel

Here, we have shown that TMEM16A and TMEM16B differ in their sensitivity to Ca2+. This is in agreement with previously published work (Scudieri et al. 2011). A recent study shows that the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A may form a part of the Ca2+ binding site (Yu et al. 2012). Specifically, evidence has been provided that two glutamates (702 and 705) are directly involved in Ca2+ binding (Yu et al. 2012). It is noteworthy that these glutamates are conserved in TMEM16B. This may indicate that the binding site for Ca2+ in TMEM16 channels involves additional residues that result in contrasting affinities for Ca2+, or that the efficacy of Ca2+ binding into channel opening differs between TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels. The [Ca2+]i–response curves for TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels are characterised by the same Hill coefficient (∼3) but different EC50 values. [Ca2+]i–response curves for native CaCCs are also characterised by a Hill coefficient ∼3 (e.g. Kuruma & Hartzell, 2000). A Hill coefficient > 1 is consistent with the idea that more than one Ca2+ binds to the channel to produce channel opening. [Ca2+]i–response curves for chimeric channels had this same slope factor. However, unlike TMEM16A-B channels that had a Ca2+ sensitivity identical to that of TMEM16A, TMEM16B-A channels were much more sensitive to Ca2+ than TMEM16B. This is consistent with the idea that the elements involved in Ca2+ sensing differ between TMEM16A and TMEM16B and that the Ca2+ binding site involves regions outside the putative pore-loop.

TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels differed in their regulation by voltage. The Boltzmann fit of the conductance versus voltage relationships revealed that the values of z for TMEM16A and TMEM16B varied by a factor ∼2; but for both channels z did not change as [Ca2+]i was increased. Thus, Ca2+ does not alter the coupling between voltage and channel opening in either TMEM16A or TMEM16B channels. The progressive leftward shift of V0.5 as [Ca2+]i was increased suggests that Ca2+ reduces the activation energy required for channel opening to a similar extent for TMEM16A and TMEM16B channels. Transfer of the putative pore of TMEM16B into TMEM16A resulted in channels with voltage-dependent properties identical to those of TMEM16B, while the complementary chimera (TMEM16B-A) preserved the voltage sensitivity observed in TMEM16B channels. The results indicate that the contribution of the putative pore-loop to voltage gating is different between the two channels.

Evidence that the putative pore-loop participates in anion permeation

Experiments involving cysteine accessibility scanning have recently identified residues within the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A that compose part of the permeation pathway (C625, G628, G629, C630, L631, M632, I636, Q637) (Yu et al. 2012). These residues are all conserved in TMEM16B. The capacity of various TMEM16 proteins to conduct anions has been examined by various groups (Duran & Hartzell, 2011; Kunzelmann et al. 2011b; Scudieri et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2012). There is some controversy regarding the capacity of TMEM16F to act as a CaCC. Indeed, TMEM16F has been shown to (i) be a non-selective cation channel (Yang et al. 2012), (ii) mediate phospholipid scramblase activity (Suzuki et al. 2010), and (iii) act as an outwardly rectifying chloride channel (Martins et al. 2011; Shimizu et al. 2013). In the HEK-293T cell heterologous expression systems, we (this study) in agreement with others (Scudieri et al. 2011; Duran et al. 2012) detected no CaCC activity associated with TMEM16F in a range of [Ca2+]i (∼0.3–80 μm). In contrast, TMEM16F elicited a prominent SCAN current in the presence of high (∼100 μm) [Ca2+]i (this study and Yang et al. 2012).

Chimeras involving the putative pore region of TMEM16F spliced into TMEM16A gave rise to proteins that reached the plasma membrane, but did not generate CaCC currents. This was not due to the fact that these chimeras have an impaired sensitivity to Ca2+, because even at very high [Ca2+]i (>70 μm) no CaCC currents were detected. However, TMEM16A-F was also not conductive for cations. Thus, despite similarities in the sequence of TMEM16A and TMEM16F channels, the putative pore-loop of TMEM16F could not be gated by the TMEM16A gating machinery. This observation may indicate that the putative pore-loop does not form a complete pore structure that can be exchanged between TMEM16 members. Indeed, at least one residue in TM5 situated close to the putative pore-loop (Q559 in TMEM16F and K584 in TMEM16A) has been shown to participate in ion selectivity of TMEM16 channels (Yang et al. 2012). This observation reinforces the idea that the ion permeation pathway in TMEM16 channels is not solely composed of the putative pore-loop region.

Membrane topology of TMEM16A

We inserted HA epitopes in five different positions within three putative extracellular loops (first, second and last) of the TMEM16A channel. We identified positions for HA-tagging in the second and last extracellular loops that were accessible to extracellular antibodies. This is in the agreement with the predicted topology model suggesting that these two protein regions are exposed to the extracellular environment. These results, combined with the finding from a recent paper (Yu et al. 2012) that determined the accessibility of extracellular loops 3 and 4, provide experimental confirmation of the predicted membrane topology of TMEM16A between TM3–5 and TM7–8.

Biological significance

CaCCs are present in many cell types and their activation may have opposite effects on cell electrical activity, depending on the reversal potential for Cl− (ECl). Furthermore, ECl can be spatially and temporally regulated within cells (Hartzell et al. 2005). For example, in vascular smooth muscle, ECl varies between −20 and −30 mV (Large & Wang, 1996; Chipperfield & Harper, 2000). Thus, activation of TMEM16A channels leads to membrane depolarisation, increased Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels and ultimately enhanced contraction. In contrast, in some neurons, such as hippocampal neurons, ECl is as negative as ∼−70 mV and opening of CaCC channels leads to hyperpolarisation and suppression of cell electrical activity (Huang et al. 2012b). The amount of Cl− that leaves or enters the cell through CaCCs depends on their functional properties and the number of channels present on the plasma membrane. Indeed, CaCC expression is altered in pathological conditions (Liang et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2012).

Here we have identified a novel structural element within the putative pore-loop of TMEM16A that regulates the number of functional channels present on the plasma membrane. Future work will be needed to elucidate the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate CaCC trafficking in various cell types and to determine how alterations in this process lead to human and animal disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Peter Brown and Professor Alison Gurney for helpful comments on this work and Dr Annukka Lehtonen for reading the manuscript.

Glossary

- CaCCs

Ca2+-activated Cl− channels

- Ex

reversal potential for X ion

- SCAN

small-conductance Ca2+-activated non-selective cation channel

- TM

transmembrane domain

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

P.T. initiated the project, designed the research, set up the experimental apparatus, trained and supervised team members; A.A. and P.T. designed the experiments and analysed the data; A.A. performed the molecular biology, immunocytochemistry and the electrophysiology (Figs 1–9), K.J.S. and H.G. did electrophysiology for Figs 8D and E and 9B; A.A. and P.T. drafted the paper while all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

P.T. holds a Research Council (RCUK) Fellowship. This research is supported via a BBSRC New Investigator Award (BB/H000259/1) to P.T., BBSRC PhD and MPhil studentships to A.A. and K.J.S, respectively, and a British Heart Foundation PhD studentship to H.G.

Authors’ present address

A. Adomaviciene, H. Garnett and P. Tammaro: Department of Pharmacology, University of Oxford, Mansfield Road, Oxford OX1 3QT, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplemental material

References

- Bader CR, Bertrand D, Schwartz EA. Voltage-activated and calcium-activated currents studied in solitary rod inner segments from the salamander retina. J Physiol. 1982;331:253–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish ME. A transient calcium-dependent chloride current in the immature Xenopus oocyte. J Physiol. 1983;342:309–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry PH, Lynch JW. Liquid junction potentials and small cell effects in patch-clamp analysis. J Membr Biol. 1991;121:101–117. doi: 10.1007/BF01870526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. The voltage sensor in voltage-dependent ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:555–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billig GM, Pal B, Fidzinski P, Jentsch TJ. Ca2+-activated Cl− currents are dispensable for olfaction. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nn.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A, Vigneron S, Brioudes E, Labbe JC, Lorca T, Castro A. Loss of human Greatwall results in G2 arrest and multiple mitotic defects due to deregulation of the cyclin B-Cdc2/PP2A balance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12564–12569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914191107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenedese V, Betto G, Celsi F, Cherian OL, Pifferi S, Menini A. The voltage dependence of the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel is modified by mutations in the first putative intracellular loop. J Gen Physiol. 2012;139:285–294. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield AR, Harper AA. Chloride in smooth muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;74:175–221. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Hahn Y, Walker DA, Nagata S, Willingham MC, Peehl DM, Bera TK, Lee B, Pastan I. Topology of NGEP, a prostate-specific cell:cell junction protein widely expressed in many cancers of different grade level. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6306–6312. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran C, Hartzell HC. Physiological roles and diseases of Tmem16/Anoctamin proteins: are they all chloride channels. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:685–692. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran C, Qu Z, Osunkoya AO, Cui Y, Hartzell HC. ANOs 3–7 in the anoctamin/Tmem16 Cl− channel family are intracellular proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C482–C493. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00140.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L, Caputo A, Ubby I, Bussani E, Zegarra-Moran O, Ravazzolo R, Pagani F, Galietta LJ. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33360–33368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CA, Cid LP, Sepulveda FV, Niemeyer MI. TMEM16 proteins: the long awaited calcium-activated chloride channels. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42:993–1001. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2009005000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DA, Badamdorj D, Kleene SJ. Spatial distribution of calcium-gated chloride channels in olfactory cilia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta LJ. The TMEM16 protein family: a new class of chloride channels. Biophys J. 2009;97:3047–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta LJ, Pagesy P, Folli C, Caci E, Romio L, Costes B, Nicolis E, Cabrini G, Goossens M, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O. IL-4 is a potent modulator of ion transport in the human bronchial epithelium in vitro. J Immunol. 2002;168:839–845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama L, Breitwieser GE. Generation of epitope-tagged proteins by inverse PCR mutagenesis. Biotechniques. 1999;26:814–816. doi: 10.2144/99265bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavet O, Pines J. Progressive activation of CyclinB1-Cdk1 coordinates entry to mitosis. Dev Cell. 2010;18:533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm DR, Frizzell RA. Anion permeation in an apical membrane chloride channel of a secretory epithelial cell. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99:339–366. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:719–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann SH, Conti F. Nonstationary noise analysis and application to patch clamp recordings. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:131–148. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd edn. Sinauer Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Wong X, Jan LY. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXV: Calcium-activated chloride channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2012a;64:1–15. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Xiao S, Huang F, Harfe BD, Jan YN, Jan LY. Calcium-activated chloride channels (CaCCs) regulate action potential and synaptic response in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2012b;74:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch RD, Joly E. An improved PCR-mutagenesis strategy for two-site mutagenesis or sequence swapping between related genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1848–1850. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, Kmit A, Jantarajit W, Martins JR, Faria D, Kongsuphol P, Ousingsawat J, Tian Y. Expression and function of epithelial anoctamins. Exp Physiol. 2011a;97:184–192. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Tian Y, Martins J, Faria D, Kongsuphol P, Ousingsawat J, Thevenod F, Roussa E, Rock J, Schreiber R. Anoctamins. Pflugers Arch. 2011b;462:195. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0975-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruma A, Hartzell HC. Bimodal control of a Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channel by different Ca(2+) signals. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:59–80. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1996;271:C435–C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauger P. Ion transport through pores: a rate-theory analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;311:423–441. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W, Ray JB, He JZ, Backx PH, Ward ME. Regulation of proliferation and membrane potential by chloride currents in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2009;54:286–293. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz S, Kongsuphol P, Mendes AI, Romeiras F, Sousa M, Schreiber R, Matos P, Jordan P, Mehta A, Amaral MD, Kunzelmann K, Farinha CM. Contribution of casein kinase 2 and spleen tyrosine kinase to CFTR trafficking and protein kinase A-induced activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4392–4404. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05517-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Jan LY. ER transport signals and trafficking of potassium channels and receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganas LN, Wang Q, Scannevin RH, Antonucci DE, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Identification of a trafficking determinant localized to the Kv1 potassium channel pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14055–14059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241403898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Tamuleviciute A, Tammaro P. TMEM16A/anoctamin 1 protein mediates calcium-activated chloride currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:2305–2314. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins JR, Faria D, Kongsuphol P, Reisch B, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Anoctamin 6 is an essential component of the outwardly rectifying chloride channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18168–18172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108094108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty A, Tan YP, Trautmann A. Three types of calcium-dependent channel in rat lacrimal glands. J Physiol. 1984;357:293–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R. A calcium-dependent transient outward current in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;215:491–497. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Droogmans G. Amazing chloride channels: an overview. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:119–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S, Dibattista M, Menini A. TMEM16B induces chloride currents activated by calcium in mammalian cells. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:1023–1038. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potapova TA, Sivakumar S, Flynn JN, Li R, Gorbsky GJ. Mitotic progression becomes irreversible in prometaphase and collapses when Wee1 and Cdc25 are inhibited. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1191–1206. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Hartzell HC. Anion permeation in Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:825–844. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JR, O’Neal WK, Gabriel SE, Randell SH, Harfe BD, Boucher RC, Grubb BR. Transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A). is a Ca2+-regulated Cl− secretory channel in mouse airways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14875–14880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach B. An overview of trafficking and assembly of neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels (Review) Mol Membr Biol. 2008;25:270–278. doi: 10.1080/09687680801960998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudieri P, Sondo E, Ferrera L, Galietta LJ. The anoctamin family: TMEM16A and TMEM16B as calcium-activated chloride channels. Exp Physiol. 2011;97:177–183. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Iehara T, Sato K, Fujii T, Sakai H, Okada Y. TMEM16F is a component of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel but not a volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying Cl− channel. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C748–C759. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms BA, Zamponi GW. Trafficking and stability of voltage-gated calcium channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0843-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sones WR, Davis AJ, Leblanc N, Greenwood IA. Cholesterol depletion alters amplitude and pharmacology of vascular calcium-activated chloride channels. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:476–484. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Umeda M, Sims PJ, Nagata S. Calcium-dependent phospholipid scrambling by TMEM16F. Nature. 2010;468:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammaro P, Ashcroft FM. A mutation in the ATP-binding site of the Kir6.2 subunit of the KATP channel alters coupling with the SUR2A subunit. J Physiol. 2007;584:743–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammaro P, Smirnov SV, Moran O. Effects of intracellular magnesium on Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 potassium channels. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:42–51. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Gatewood C, Neeb ZP, Bulley S, Adebiyi A, Bannister JP, Leo MD, Jaggar JH. TMEM16A channels generate Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1819–H1827. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00404.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Kongsuphol P, Hug M, Ousingsawat J, Witzgall R, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Calmodulin-dependent activation of the epithelial calcium-dependent chloride channel TMEM16A. FASEB J. 2011;25:1058–1068. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-166884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Yang H, Zheng LY, Zhang Z, Tang YB, Wang GL, Du YH, Lv XF, Liu J, Zhou JG, Guan YY. Downregulation of TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel contributes to cerebrovascular remodeling during hypertension by promoting basilar smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2012;125:697–707. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q, Yu K, Perez-Cornejo P, Cui Y, Arreola J, Hartzell HC. Voltage- and calcium-dependent gating of TMEM16A/Ano1 chloride channels are physically coupled by the first intracellular loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8891–8896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102147108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Kim A, David T, Palmer D, Jin T, Tien J, Huang F, Cheng T, Coughlin Shaun R, Jan Yuh N, Jan Lily Y. TMEM16F forms a Ca2+-activated cation channel required for lipid scrambling in platelets during blood coagulation. Cell. 2012;151:111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, Raouf R, Shin YK, Oh U. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Duran C, Qu Z, Cui YY, Hartzell HC. Explaining calcium-dependent gating of anoctamin-1 chloride channels requires a revised topology. Circ Res. 2012;110:990–999. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.264440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Gomez B, Watanabe I, Thornhill WB. Amino acids in the pore region of Kv1 potassium channels dictate cell-surface protein levels: a possible trafficking code in the Kv1 subfamily. Biochem J. 2005;388:355–362. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.