Abstract

The RAF kinase family is essential in mediating signal transduction from RAS to ERK. BRAF constitutively active mutations correlate with human cancer development. However, the precise molecular regulation of BRAF activation is not fully understood. Here we report that BRAF is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at lysine 578 within its kinase domain once it is activated by gain of constitutively active mutation or epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation. Substitution of BRAF lysine 578 with arginine (K578R) inhibited BRAF-mediated ERK activation. Furthermore, ectopic expression of BRAF K578R mutant inhibited anchorage-independent colony formation of MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Our studies have identified a previously unrecognized regulatory role of Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in BRAF-mediated normal and oncogenic signalings.

The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway is critical in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis1. The RAF proteins play an essential role in growth factor-mediated signal transduction from the cell surface to nucleus. BRAF is the main isoform of RAF family that relays the signal transduction from RAS to MEK2,3. Growth factors bind to and activate their receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) on cell membrane, which in turn convert RAS from an inactive GDP-bound to an active GTP-bound state. The binding of RAS-GTP and BRAF recruits BRAF to the cell membrane, where BRAF is phosphorylated at Thr 599 and Ser 602 with enhanced serine/threonine kinase activity4. The activated BRAF leads to phosphorylation and activation of MEK1/2, which in turn activates ERK1/2 to phosphorylate downstream targets in the cytoplasm and nucleus5,6.

Many types of human cancers are associated with the deregulation of RAS/RAF/ERK signaling pathway. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a typical RTK that mediates RAS/RAF/ERK activation7. Amplification and mutation of EGFR is involved in initiation and development of many human cancers8,9. Oncogenic substitution of RAS at Gly 12 or Gly 13, which abrogates the association of RAS and GTPase-activating proteins (GAP), keeps RAS in a constitutive GTP-bound and hyperactive state, and causes development of several types of human cancers10,11. BRAF V600E mutation renders BRAF constitutively active and is responsible for more than 90% of somatic BRAF mutations seen in human tumors12. BRAF K601E mutation found in some papillary thyroid cancer patients has a similar effect as that of V600E mutation13,14. However, the regulation of ERK activation induced by oncogenic activation of EGFR/RAS/RAF remains to be fully understood.

Protein ubiquitination plays essential roles in controlling protein function, stability, and localization15. Ubiquitin (Ub) is a highly conserved protein that covalently attaches to lysine (Lys or K) residue of target proteins. Lys48-linked polyubiquitination is the main ubiquitin chain that mediates proteasome-dependent degradation of the modified proteins; whereas Lys63-linked polyubiquitination serves as a molecular platform for protein/protein interaction important for kinase activation, receptor endocytosis, protein trafficking, anti-viral response and DNA damage repair, which are independent of proteolytic degradation function16,17. Recently, Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of kinases has been shown to be involved in the regulation of specific kinase-mediated signaling, such as in NF-κB18,19 and AKT pathways20,21.

To clarify whether protein ubiquitination is involved in the activity of BRAF and its roles in BRAF mediated signalings, several different types of cancer cell lines with BRAF constitutively active mutation were used to investigate the ubiquitination status of the protein. The result shows Lys63-linked ubiquitination at Lys 578 residue is essential for the activation of BRAF with the oncogenic mutations. Furthermore, EGF stimulation induces Lys63-linked polyubiquitin modification at BRAF Lys 578 residue which is required for EGF-mediated ERK activation. Together, our results provide biochemical evidence that Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578 is essential for BRAF-mediated normal and oncogenic signalings.

Results

Activated BRAF is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in human cancer cell lines

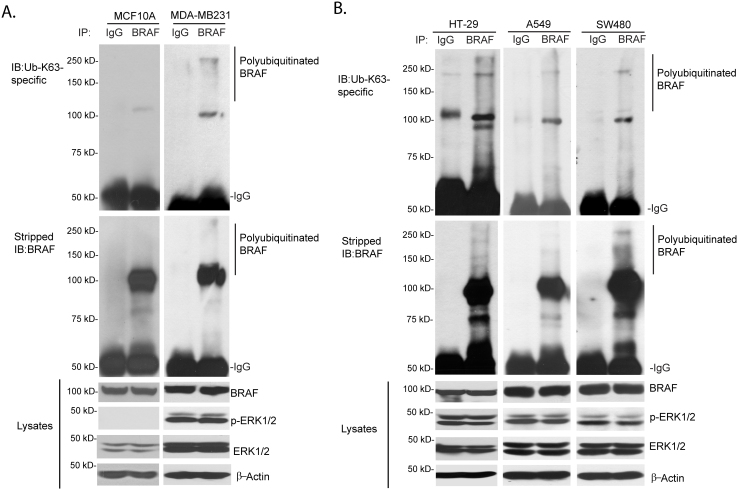

To test whether Lys63-linked polyubiquitination plays a role in BRAF activation and BRAF-mediated activation of downstream signaling pathway, we examined the Lys63-linked polyubiquitination status of BRAF in several human cell lines with or without BRAF or RAS oncogenic mutations, including MCF10A (BRAF wild-type), MDA-MB-231 (KRAS G13D, BRAF G464V)22, HT-29 (BRAF V600E)23, A549 (KRAS G12S)24, and SW480 (KRAS G12V)25. As shown in Fig. 1A and 1B, using anti-Ub-K63-specific antibodies, we found that the endogenous BRAF proteins were modified with Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chain in these cancer cells harboring BRAF or RAS oncogenic mutations, in comparison with a non-tumorigenic breast epithelial cell line, MCF10A, which possesses wild-type RAS and BRAF.

Figure 1. Activated BRAF is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in human cancer cell lines.

(A) Endogenous BRAF with constitutive active mutation is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chain. MCF10A cells (wild-type BRAF) and MDA-MB-231 cells (with KRAS G13D, BRAF G464V mutation) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-normal IgG or BRAF antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-Ub-K63-specific antibodies to detect the presence of BRAF with Lys 63-linked polyubiquitination. (B) Hyperactivated RAS induces BRAF modification by Lys 63-linked polyubiquitination. HT29 (BRAF V600E mutation), A549 (with KRAS G12S mutation), and SW480 cell lines (with KRAS G12V mutation) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-normal IgG or BRAF antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-Ub-K63-specific antibodies to detect the presence of Lys63-ubiquitinated endogenous BRAF. Cropped blots were used under the same experimental conditions.

BRAF with constitutively active mutation is linked with Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains

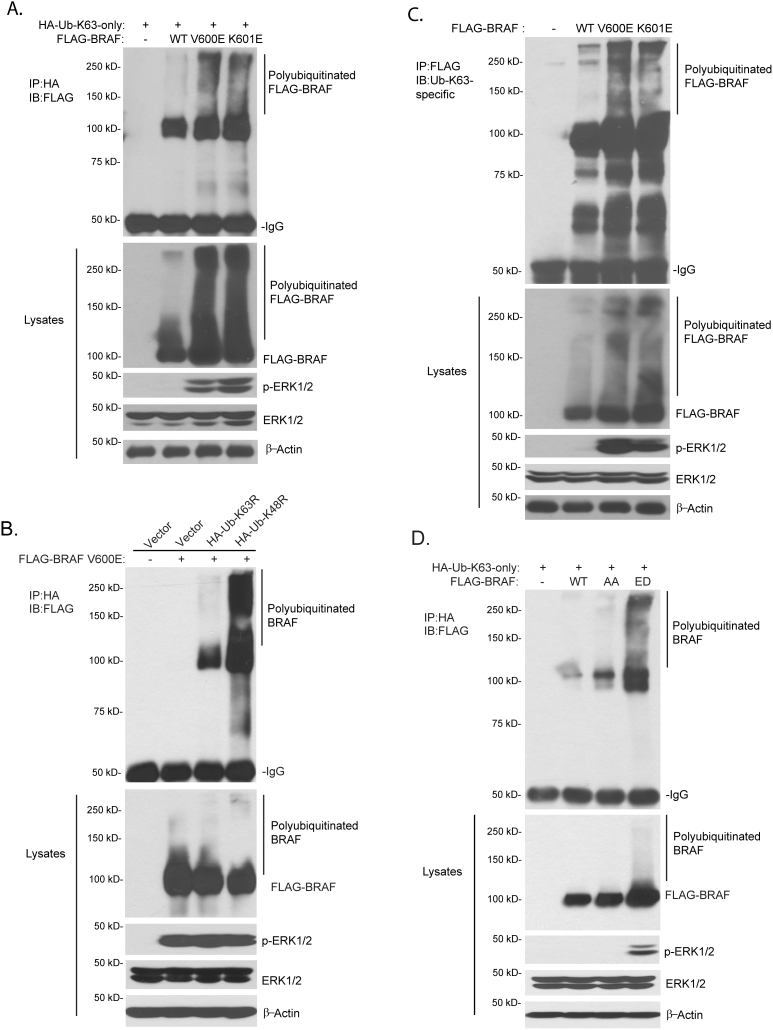

To further determine whether BRAF with constitutively active mutation is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination, expression vectors encoding FLAG-BRAF wild-type or constitutively active V600E or K601E mutants were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with HA-Ub containing one lysine only at position 63 (HA-Ub-K63-only). As shown in Fig. 2A, we found that BRAF V600E and K601E proteins were strongly polyubiquitinated with Lys63-ubiquitin chain compared with BRAF wild-type. Consistent with this result, we found that FLAG-BRAF V600E proteins were strongly modified by Ub K48R but not Ub K63R mutant proteins (Fig. 2B). To further confirm this result, expression vectors encoding FLAG-BRAF wild-type or constitutively active mutants were transfected into HEK-293T cells. Then FLAG-BRAF proteins in the cell lysate were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-Ub-K63-specific antibodies. Unlike BRAF wild-type, BRAF V600E and K601E proteins were modified by endogenous Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains (Fig. 2C). BRAF phosphorylation at Thr 599 and Ser 602 is essential for its activation in physiological condition. BRAF T599A-S602A double mutant (BRAF-AA) abolishes activation of BRAF whereas BRAF T599E-S602D double mutant (BRAF-ED) renders BRAF constitutively active4. We found that BRAF-ED, but not BRAF-AA mutant, was modified with Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and was able to activate endogenous ERK (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. BRAF with constitutively active mutation is linked with Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains.

(A) BRAF with constitutively active mutation was linked with HA-Ub-K63-only. The expression vector encoding full length FLAG-BRAF WT or constitutively active V600E or K601E mutant was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with HA-Ub-K63-only expression vector. Lys 63-polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. (B) BRAF with V600E constitutive active mutation was modified by Lys63- but not Lys48-linked polyubiquitination. Empty vector or expression vector encoding HA-Ub-K63R or -K48R was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with FLAG-BRAF. Ubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF proteins were detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. (C) BRAF with constitutively active mutation was endogenously modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination. The expression vector encoding full length FLAG-BRAF WT, constitutively active V600E or K601E mutant was transfected into HEK-293T cells. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-Ub-K63-specific antibodies. (D) BRAF ED mutant was modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains compared with BRAF WT or BRAF AA mutant. Expression vector encoding FLAG-BRAF WT, AA and ED were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with HA-Ub-K63-only vector, respectively. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. Cropped blots were used under the same experimental conditions.

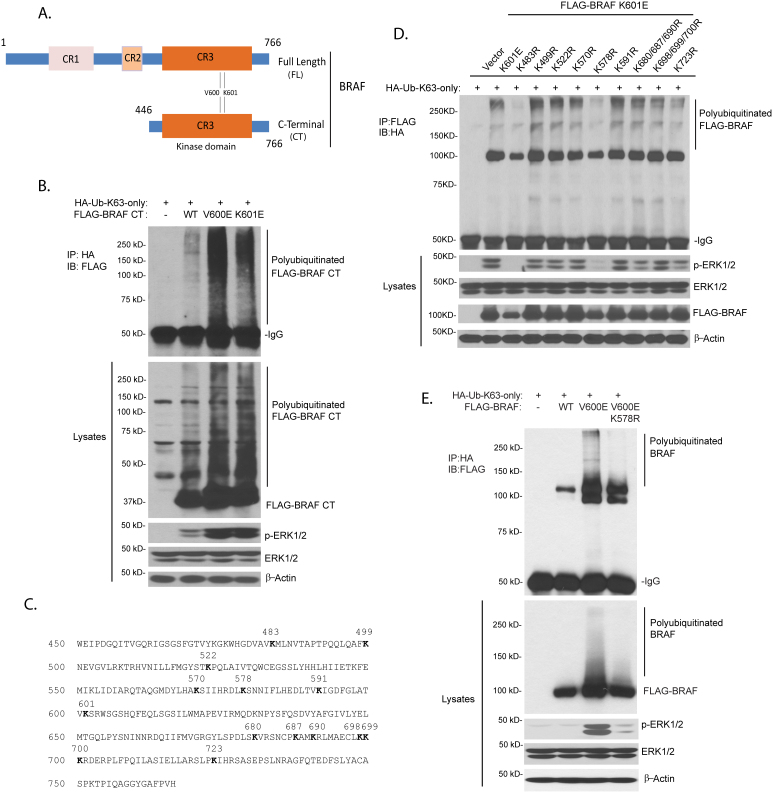

BRAF with constitutively active mutation is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578 within its kinase domain

To determine the role of Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in BRAF activation and BRAF-mediated ERK activation, it is essential to map BRAF Ub lysine acceptor site(s). To determine the location of Ub lysine acceptor site on BRAF, we generated the N-terminal deletion constructs of BRAF wild-type, V600E and K601E mutants in which the BRAF regulatory domain to amino acid 446 was deleted (BRAF CT) (Fig. 3A). Then these BRAF CT mutants were co-transfected with HA-Ub-K63-only expression vectors into HEK-293T cells. As shown in Fig. 3B, BRAF CT V600E and K601E proteins were strongly modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination compared with the BRAF CT wild-type. Consistent with that result, BRAF CT V600E and K601E induced a stronger ERK activation compared with BRAF CT wild-type. Therefore, we reasoned that one or more Lys residues within BRAF C-terminal kinase domain (446–766 amino acids) may serve as the Ub Lysine acceptor site(s).

Figure 3. BRAF with constitutively active mutation is modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578 within its kinase domain.

(A) Schematic view of BRAF full length (FL) and BRAF C-terminal (CT). (B) BRAF C-terminal (CT) with constitutively active mutation was modified with Lys63-linked polyubiquitination. The expression vector encoding FLAG-BRAF CT wild-type, constitutively active V600E or K601E mutant was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with HA-Ub-K63-only expression vector. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. (C) BRAF sequence with the evolutionary conserved lysine residues within its C-terminal kinase domain amino acids indicated. (D) BRAF with K601E mutation was modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578. Expression vector encoding HA-Ub-K63-only was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with control vector or FLAG-BRAF K601E or K601E plus other lysine to arginine mutants. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. (E) BRAF with V600E mutation was modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578. Expression vector encoding FLAG-BRAF WT, V600E or V600E plus K578R double mutant was co-transfected into HEK-293T cell with HA-Ub-K63-only vector. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. Cropped blots were used under the same experimental conditions.

BRAF contains 21 lysine residues within its kinase domain (Fig. 3C). To identify the possible Ub lysine acceptor site(s) in BRAF with constitutively active mutation, each of 14 evolutionary conserved Lys residues in FLAG-BRAF-K601E full length (or CT) were systematically replaced with an Arg residue, which maintains the positive charge but is not able to serve as an acceptor site for Ub modification. The expression vectors encoding FLAG-BRAF-K601E full length (or CT) and mutants with different Lys to Arg mutations were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with HA-Ub-K63-only expression vectors. Among the 14 Lys to Arg mutants examined, only K483R and K578R mutants failed to induce BRAF polyubiquitination as well as ERK activation compared with all the other mutants (Fig. 3D, Fig. S1A). Consistent with these results, luciferase reporter analysis showed that BRAF-K601E CT with K483R or K578R mutation failed to induce AP-1-dependent luciferase reporter gene expression whereas BRAF-K601E CT and other mutants induced a higher level of AP-1 reporter activity in HEK-293T cells (Fig. S1B). Since the BRAF Lys 483 residue is a conserved lysine residue in the ATP binding pocket essential for coordinating kinase ATP-binding and activation26, it can be inferred that Lys 578 is the predominant Lys63-linked Ub acceptor site for BRAF polyubiquitination. In addition, we tested the impact of K578R mutation in BRAF with constitutively active V600E mutation. As shown in Fig. 3E, we found that BRAF with V600E-K578R double mutations failed to be modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and resulted in significantly decreased ERK phosphorylation compared with BRAF with V600E mutation. Conforming to these results, we found that BRAF-ED with K578R mutation failed to be modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and resulted in significantly decreased ERK phosphorylation compared to BRAF-ED mutant (Fig. S2). As indicated by previous studies indicate that BRAF Lys 578 residue is on the surface of the protein structure and is exposed to solvent27 (Fig. S3). Therefore, BRAF K578R mutation should not induce any significant structural perturbation. These results suggest that Lys 578 serves as an acceptor site for Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and activation of BRAF with constitutive active mutation.

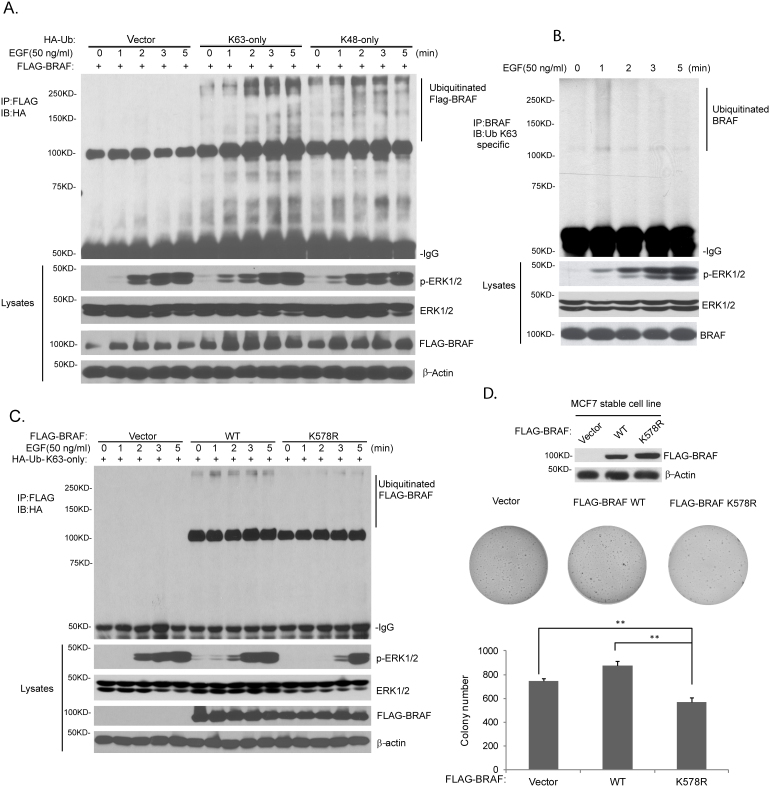

EGF induces Lys63-linked BRAF polyubiquitination at Lys 578

Since EGF induces BRAF activation via EGFR/RAS-GTP, we hypothesized that EGF induces BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in physiological condition. Indeed, Lys63-linked BRAF polyubiquitination was detected in serum starved HEK-293T cells transfected with different HA-tagged ubiquitin constructs after EGF treatment (Fig. 4A). To further test this hypothesis, HEK-293T cells were serum starved and treated with human EGF. As shown in Fig. 4B, EGF rapidly induced Lys63-linked endogenous BRAF polyubiquitination and ERK activation. Furthermore, we found that BRAF K578R mutant inhibited EGF-induced BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and delayed ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. EGF induces Lys63-linked BRAF polyubiquitination at Lys 578.

(A) BRAF was modified with Lys63-linked polyubiquitination after EGF treatment. Expression vector encoding FLAG-BRAF wild-type was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with HA-Ub with Lys63- or Lys48-only expression vector. After 24 hours, cells were starved for 16 hours and treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) at time points indicated. Polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. (B) Endogenous BRAF was modified by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination after EGF treatment. HEK-293T cells were starved for 16 hours and treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) at time points indicated. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-BRAF antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-Ub-K63-specific antibodies. (C) EGF induced BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578, which was required for EGF-induced ERK activation. Expression vector encoding empty vector, FLAG-BRAF wild-type or K578R mutant was co-transfected into HEK-293T cell with HA-Ub-K63-only expression vector. After 24 hours, cells were starved for 16 hours and treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) at time points indicated. Lys63-linked polyubiquitinated FLAG-BRAF was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. (D) BRAF with K578R mutation blocked anchorage-independent growth of MCF7 breast cancer cells. MCF7 cells with stable expression of empty vector, FLAG-BRAF wild-type or K578 mutant was used for colony formation assay in triplicates. **p < 0.01. Cropped blots were used under the same experimental conditions.

To further examine the role of Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in BRAF-mediated function in the cancer cells, MCF7, a breast cancer cell line with wild-type BRAF, was used to generate stable cell line that express empty vector or FLAG-BRAF wild-type or K578R mutant. Colony formation assay was performed to examine the effect of BRAF K578R on cell behavior. As shown in Fig. 4D, MCF7 cells with FLAG-BRAF K578R stable expression displayed significantly decreased colony number compared with the MCF7 cells with stable expression of empty vector or FLAG-BRAF wild-type. Taken together, these results indicate that Lys 578 residue is an acceptor site for Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of BRAF in response to EGF stimulation. In addition, Lys63-linked BRAF polyubiquitination is required for EGF-induced ERK activation as well as anchorage-independent colony formation potential of MCF7 breast cancer cell line.

Discussion

It is worth noting that KRAS is subject to modification by monoubiquitination, which increases KRAS GTP loading and the affinity to its specific downstream activity28. Whereas the ubiquitination of HRAS stabilizes the association of HRAS with endosomes and upregulates its activity to induce the activation of downstream signaling29. Here, we demonstrate that BRAF, a downstream effector of RAS, is also modulated by ubiquitination during its activation.

Previous studies suggested that the kinase domain of BRAF wild type and constitutively active V600E mutant differ in their conformation and the latter has increased dimerization potential6,30. With increased complexity for BRAF kinase regulation, our results demonstrate that BRAF with constitutive mutation is subject to modification by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination. Since substitution of constitutively active BRAF V600E or K601E mutant Lys 578 with Arg abolishes its Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and BRAF V600E or K601E-mediated ERK activation, we conclude that the Lys63-linked polyubiquitination is essential in BRAF V600E or K601E mutant -mediated oncogenic signaling.

Our finding shows that EGF induces Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of BRAF, which may serve as a platform to assemble BRAF-containing signaling complex to mediate the activation of downstream signaling. Interestingly, a lysine to arginine mutation at Lys 578 of BRAF blocks EGF induced BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and ERK activation (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that Lys 578 is the predominant Ub acceptor site of BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination induced by EGF and BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination plays an essential role in EGF-induced ERK activation.

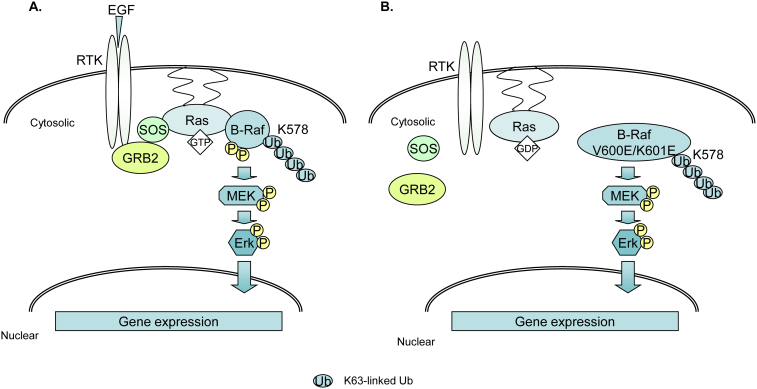

Collectively, our study reveals that BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578 residue within its kinase domain upon its activation is required for BRAF signaling in normal or oncogenic settings. In the light of the data presented here and in previous reports, we proposed two working models to present an integral modulation of BRAF activation by Lys63-linked polyubiquitination (Fig. 5). Obviously, more studies are needed to identify the specific E3 ligase(s) and deubiquitinating enzyme(s) that are responsible for the positive and negative regulation of BRAF Lys63-linked polyubiquitination. Further characterization of ubiquitination control in BRAF oncogenic signaling will help us to identify novel molecular therapeutic targets for curing the cancers harboring RAS and BRAF oncogenic mutations.

Figure 5. Working models for the role of Lys63-linked polyubiquitination in BRAF activation.

(A) Normal BRAF activation. Upon EGF binding to its receptor, the Ras-GTP recruits BRAF and induces its phosphorylation at Thr 599-Ser 602 residues and Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578 within its kinase domain, which in turn mediates the activation of MEK-ERK and regulates downstream gene expression. (B) Oncogenic BRAF activation. BRAF with constitutively active mutation gains its Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys 578 to activate downstream effector gene independent of RAS activity.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

HEK-293T, colon cancer cell line HT-29, SW480, breast cancer cell line MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and alveolar adenocarcinoma cell line A549 were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. MCF10A cells were cultured in the standard, the Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12, 1:1) containing 17 mM glucose, and supplemented with 5% horse serum, 10 mg/L insulin, 20 μg/L epidermal growth factor, 50 μg/L cholera toxin, 50 mg/L hydrocortisone, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified environment at 37°C with 5% CO2. HEK-293T and MCF7 were transfected with mammalian expression plasmids using Fugene XtremeGENE 9 (Roche) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively.

Expression vectors

A cDNA construct containing the full length open reading frame of the wild-type human BRAF was subcloned into the Flag-tagged mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1. Point mutations were made by site-directed PCR mutagenesis and verified by DNA sequencing analysis. Ubiquitin K63R, K48R and ubiquitin with all lysine to arginine mutation except Lys 63 or Lys 48 were sub-cloned into mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 with HA-tag at their N-terminal and verified by DNA sequencing analysis. Their expression in HEK-293T cells after transfection were confirmed by immunoblotting analysis with anti-HA antibodies (Fig. S4).

Establishment of stable cell lines

Human breast cancer cell line MCF7 was transfected with FLAG-BRAF wild type, FLAG-BRAF-K578R, and control vector using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then G418 (1.3 mg/ml) was added to these transfected cells. After 15 days selection, stable cell lines were established. Western blotting was used to validate the expression of different BRAF constructs.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2 and secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The anti-FLAG antibody (M2) and anti-β-actin antibodies as well as protease and phosphatase inhibitors were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies for HA epitope, BRAF (F-7) and Protein A-agarose beads were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Ub-K63-specific antibody was from EMD Millipore (Temecula, CA). Rabbit anti-Flag antibodies were generated and purified by Genemed Synthesis Inc. (San Antonio, TX). Human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

To prepare the total cell lysates, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS on ice, then were lysed by adding lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 135 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μg/ml aprotinin,10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM Benzamidine, 20 mM disodium p-nitrophenylphosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 3 mM EDTA, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail A and B). Then the cell lysate were boiled in the presence of 1% SDS and then diluted with lysis buffer to 0.1% SDS in order to disrupt noncovalent protein-protein interactions. After collecting the cell lysate by 15000×g centrifugation for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant were incubated with the indicated antibodies for 3 h at 4°C. Followed by adding Protein A-agarose beads and rotated for 3 h at 4°C. The precipitates were washed four times in cold washing buffer (20 mM HEPES,pH 7.7, 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.05% Triton X-100), then the beads were re-suspended in gel loading buffer and boiled for 5 min. The immunoprecipitates or the whole cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were probed with the appropriate antibodies. The IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were used as the secondary antibodies. The proteins were detected by using the ECL-Plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare).

Luciferase reporter assay

HEK-293T cells were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured overnight in 12-well plates. AP-1-dependent firefly luciferase reporter and effector plasmids were co-transfected along with the Renilla luciferase plasmid into HEK-293T cells. Forty eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested in lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The relative luciferase activity was calculated by dividing the firefly luciferase activity by the Renilla luciferase activity. Data represents three independent experiments performed in triplicates.

Colony formation assays

The 6-well plate was filled with 2 ml of 0.5% agar gel in DMEM with 10% FBS as lower gel. Cell numbers of MCF7 stable cell lines were counted (1 × 104) and mixed with 1.5 ml of 0.3% agar gel in DMEM with 10% FBS. The mixture was added on the concretionary lower gel and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 15 days. The cells were stained with 5 mg/ml MTT to detect the existence of colony formation of each cell lines in the plate. The colony number was counted by 1-D gel image colony counting software from Bio-Rad.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean ± S.D. P-values were calculated using unpaired two-tailed student's t-test. A p-value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

L.A., W.J. and Y.Y. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and edited the manuscript. L.A. wrote the draft of the manuscript. H.Z. and J.H.Y. obtained funding, supervised the project and edited the manuscript. N.Z., Y.H.F., Y.Y. and Z.C.S. analyzed the results and commented on the manuscript. G.F.X. analyzed the 3-D structure of BRAF. G.L. built some initial constructs. L.L., Y.L.Z. and J.C. revised the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristine Yang for editing our manuscript. This work was supported in part by the grants from the Fleming-Davenport Award from Texas Medical Center (H.Z.), Start-up funding support from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (H.Z.), the University Cancer Foundation via the Institutional Research Grant program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (H.Z.), and from NIH/NINDS 1R01NS072420 (J.Y.). Wei Jia and Jin Cheng are the recipients of China Scholarship Council training grants.

References

- Avruch J. MAP kinase pathways: the first twenty years. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1773, 1150–1160 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niault T. S. & Baccarini M. Targets of Raf in tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 31, 1165–1174 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellbrock C., Karasarides M. & Marais R. The RAF proteins take centre stage. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 5, 875–885 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. H. & Guan K. L. Activation of B-Raf kinase requires phosphorylation of the conserved residues Thr598 and Ser601. The EMBO journal 19, 5429–5439 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W. Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. The Biochemical journal 351 Pt 2, 289–305 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. F. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 4, 373–384 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts P. J. & Der C. J. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 26, 3291–3310 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steelman L. S. et al. Dominant roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell cycle progression, prevention of apoptosis and sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs. Cell Cycle 9, 1629–1638 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W. Ras/Raf signalling and emerging pharmacotherapeutic targets. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy 3, 709–718 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffzek K. et al. The Ras-RasGAP complex: structural basis for GTPase activation and its loss in oncogenic Ras mutants. Science 277, 333–338 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N. & Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer 10, 116–129 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell-Dorris E. R., O'Leary J. J. & Sheils O. M. BRAFV600E: implications for carcinogenesis and molecular therapy. Molecular cancer therapeutics 10, 385–394 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovisco V. et al. A new BRAF gene mutation detected in a case of a solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Human pathology 36, 694–697 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennelli G. et al. BRAF(K601E) mutation in a patient with a follicular thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association 21, 1393–1396 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K. & Dikic I. Ubiquitylation and cell signaling. The EMBO journal 24, 3353–3359 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A. & Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annual review of biochemistry 67, 425–479 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. J. & Sun L. J. Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Molecular cell 33, 275–286 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. et al. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at lysine 158 is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-1beta-induced IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 5347–5360 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaug B., Jiang X. & Chen Z. J. The role of ubiquitin in NF-kappaB regulatory pathways. Annual review of biochemistry 78, 769–796 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. L. et al. The E3 ligase TRAF6 regulates Akt ubiquitination and activation. Science 325, 1134–1138 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. H. et al. The Skp2-SCF E3 Ligase Regulates Akt Ubiquitination, Glycolysis, Herceptin Sensitivity, and Tumorigenesis. Cell 149, 1098–1111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollestelle A., Elstrodt F., Nagel J. H., Kallemeijn W. W. & Schutte M. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase or RAS pathway mutations in human breast cancer cell lines. Molecular cancer research : MCR 5, 195–201 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahallad A. et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 483, 100–103 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumov G. N. et al. Combined vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) blockade inhibits tumor growth in xenograft models of EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 15, 3484–3494 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. L. et al. KRAS Mutation Is a Predictor of Oxaliplatin Sensitivity in Colon Cancer Cells. PloS one 7, e50701 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie P. et al. The crystal structure of BRAF in complex with an organoruthenium inhibitor reveals a mechanism for inhibition of an active form of BRAF kinase. Biochemistry 48, 5187–5198 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L. et al. Non-oxime inhibitors of B-Raf(V600E) kinase. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 21, 1243–1247 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A. T. et al. Ubiquitination of K-Ras enhances activation and facilitates binding to select downstream effectors. Science signaling 4, ra13 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jura N., Scotto-Lavino E., Sobczyk A. & Bar-Sagi D. Differential modification of Ras proteins by ubiquitination. Molecular cell 21, 679–687 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roring M. et al. Distinct requirement for an intact dimer interface in wild-type, V600E and kinase-dead B-Raf signalling. The EMBO journal 31, 2629–2647 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information