Abstract

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) relapsing after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) presents a major clinical challenge. In the present investigation, we evaluated brentuximab vedotin, a CD30-directed Ab-drug conjugate, in 25 HL patients (median age, 32 years; range, 20-56) with recurrent disease after alloSCT (11 unrelated donors). Patients were > 100 days after alloSCT, had no active GVHD, and received a median of 9 (range, 5-19) prior regimens. Nineteen (76%) had refractory disease immediately before enrollment. Patients received 1.2 or 1.8 mg/kg of brentuximab vedotin IV every 3 weeks (median, 8 cycles; range, 1-16). Overall and complete response rates were 50% and 38%, respectively, among 24 evaluable patients. Median time to response was 8.1 weeks, median progression-free survival was 7.8 months, and the median overall survival was not reached. Cough, fatigue, and pyrexia (52% each), nausea and peripheral sensory neuropathy (48% each), and dyspnea (40%) were the most frequent adverse events. The most common adverse events ≥ grade 3 were neutropenia (24%), anemia (20%), thrombocytopenia (16%), and hyperglycemia (12%). Cytomegalovirus was detected in 5 patients (potentially clinically significant in 1). These results support the potential utility of brentuximab vedotin for selected patients with HL relapsing after alloSCT. These trials are registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01026233, NCT01026415, and NCT00947856.

Introduction

Despite modern treatment regimens, advanced Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) recurs after primary therapy in up to 40% of patients.1–3 After initial relapse, autologous stem cell transplantation (autoSCT) can lead to durable responses in approximately 50% of patients with chemosensitive relapse.4,5 However, relapse remains common, with the worst outcomes in those with positive functional imaging or chemoresistant disease before transplantation.5–10 The optimal therapeutic course for post-autoSCT relapse has not been established; however, 1 option may include consolidating a treatment response with an allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) with the goal of inducing long-term disease control by the immune-mediated graft-versus-lymphoma effect.11–13 Although long-term disease-free survival can be achieved with this approach, most studies have shown that relapses occur in approximately 50% of patients, with the higher rates in those with chemoresistant disease and extensive prior therapies.11,14 Once relapse occurs after alloSCT, the outcomes are poor, with less than half of patients surviving 3 years12–17; few data are available regarding effective therapeutic options.

Because CD30 is expressed on malignant Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg cells of HL but has limited expression on normal cells, CD30 is an attractive target for anti-HL therapy. Brentuximab vedotin (ADCETRIS) comprises a chimeric Ab specific for human CD30 conjugated by a protease-cleavable linker to the microtubule-disrupting agent monomethyl auristatin E. After binding to CD30-expressing cells, the complex is internalized, and monomethyl auristatin E is released, disrupting the microtubule network and subsequently inducing cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis.18,19

In a phase 1, dose escalation trial that enrolled 45 patients with relapsed or refractory CD30+ hematologic malignancies,20 objective responses, including 11 complete remission (CRs), were observed in 17 patients and tumor regression was observed in 86% of evaluable patients. Seventy-three percent of patients in that trial had undergone autoSCT. Brentuximab vedotin (1.8 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks) was subsequently evaluated in a pivotal phase 2 study of 102 patients with relapsed/refractory CD30+ HL after autoSCT.21 Objective responses were induced in 75% of patients, with CRs observed in 34% of patients, as determined by an independent radiology review facility. The estimated 12-month survival was 89% and the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.6 months. Adverse events associated with brentuximab vedotin were typically grade 1 or 2 and able to be managed through standard supportive care. Cumulative peripheral neuropathy, the most clinically meaningful adverse event, improved or resolved completely in 80% of patients during the study. Patients who had previously received an alloSCT were excluded from both of these trials.

Based on the efficacy and tolerability of brentuximab vedotin in patients who had undergone autoSCT, we hypothesized that this agent may be particularly appealing for the treatment of patients with HL recurring after alloSCT. In the present report, we describe a distinct, previously unpublished cohort of 25 heavily pretreated patients with CD30+ HL that relapsed after alloSCT (median of 9 treatment regimens; range, 5-19) and summarize the safety, efficacy, and potential impact of brentuximab vedotin on the unique post-alloSCT immunologic milieu.

Methods

Patients

Patients included in the cohort were adults with histologically confirmed CD30+ HL. Patients were required to have measurable disease and the HL had to have relapsed, been refractory, or progressed after at least 1 prior systemic salvage chemotherapy and after alloSCT. The need for treatment was determined by the treating physician. Patients were excluded from study participation if they had received alloSCT within 100 days or autoSCT within 4 weeks before the first dose of study drug; active acute or chronic GVHD of any grade; concurrent therapy with corticosteroids ≥ 20 mg/d prednisone equivalent; or active systemic viral, bacterial, or fungal infection requiring antimicrobial therapy within 2 weeks before the first dose of study drug. Patients were also excluded if they had an absolute neutrophil count < 1000/μL, platelets < 50 000/μL, or an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status > 1. The studies were approved by the institutional review board at each study site and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before any study-specific procedures, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Brentuximab vedotin therapy

Patients were treated with brentuximab vedotin as part of 3 open-label, nonrandomized multicenter trials. All patients initially participated in 1 of 2 clinical pharmacology studies; some patients received additional treatment cycles in a treatment extension study. These trials are registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov as: NCT01026233, “Cardiac Safety Study of Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35)”; NCT01026415, “Clinical Pharmacology Study of Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35)”; and NCT00947856, “An SGN-35 Trial for Patients Who Have Previously Participated in an SGN-35 Study.” All 25 patients received brentuximab vedotin at protocol-specified doses of 1.8 mg/kg (n = 19) or 1.2 mg/kg (n = 6) every 3 weeks administered intravenously over 30 minutes. In the treatment extension study, the dose level was increased to 1.8 mg/kg for 4 of the 6 patients who had initial doses of 1.2 mg/kg. Patients could continue therapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred. Additional details regarding administration of brentuximab vedotin are provided in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Data collection

Clinical trial data were collected prospectively at 10 sites, 9 in the United States and 1 in Germany, beginning in December 2009. Safety assessments included evaluation of adverse events, routine hematology and serum chemistry tests (conducted at local laboratories), and assessment of antitherapeutic Abs (conducted at a central laboratory).

Disease assessments were conducted by the investigator based on the Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma22 according to the institutional standard of care. Patients were considered to have disease refractory to prior therapy if they did not have an objective response or if they had a partial remission (PR) or CR but relapsed within 6 months.

To further characterize the underlying malignancy and the alloSCT experience and outcome, the following data were collected retrospectively in June through August 2011: investigator assessment of response in relation to prior therapies, details of alloSCT (ie, disease state before alloSCT, donor type, and conditioning regimen), history of acute and chronic GVHD, and history of clinically significant infections between alloSCT and first dose of brentuximab vedotin. Information on clinically significant infections was solicited based on recommendations described previously.23 Specific infections of interest included, but were not limited to, EBV, CMV, Aspergillus and other fungal infections, Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia, and any infection that was life threatening or considered clinically significant by the investigator.

CMV PCR results presented in this study were generated by a centralized testing laboratory at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA). CMV data are not available for all patients because the 3 protocols were amended to include routine CMV surveillance for post-alloSCT patients. In addition to prospective testing after the amendment, some centralized CMV testing was performed retrospectively. In addition, in the event of any positive CMV PCR test, the amendments recommended preemptive therapy as described previously23 and specified the requirements for continued dosing with brentuximab vedotin.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by representatives of Seattle Genetics Inc, and all authors had access to the primary clinical trial data. Patient characteristics; adverse events; outcomes of prior therapies; and the details of alloSCT, GVHD, and clinically significant infections were summarized descriptively. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to estimate PFS. Univariate analyses were used to assess whether the following factors were associated with the outcome of brentuximab vedotin therapy: total number of prior treatment regimens; prior autoSCT, prior donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI), prior external beam radiation, and number of prior systemic chemotherapy regimens; donor source for alloSCT (matched related, matched unrelated, or other) and time to progressive disease (< 6 months vs ≥ 6 months) after alloSCT; number of regimens between alloSCT and brentuximab vedotin therapy; objective response (CR + PR) and time to progressive disease (< 6 months vs ≥ 6 months) after the most recent prior regimen; and history of prior GVHD. We evaluated potential associations of those factors with objective response using logistic regression, and PFS using Cox regression; all P values were 2-sided. Statistical analyses were generated using SAS Version 9.2 or higher software.

Results

Patient history before treatment with brentuximab vedotin

Patient characteristics.

Patient demographic and disease characteristics are provided in Table 1. The median age was 32 years (range, 20-56) and 13 patients (52%) were male. The median total number of prior treatment regimens was 9 (range, 5-19), 19 (76%) patients had received prior autoSCT, and 6 (24%) patients had at least 1 prior DLI.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics prior to first dose of brentuximab vedotin

| N = 25 | |

|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 32 (20-56) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 13 (52) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 9 (36) |

| 1 | 16 (64) |

| Median time from HL diagnosis to first dose of brentuximab vedotin, mo (range) | 72 (19-159) |

| Total number of prior regimens, median (range)* | 9 (5-19) |

| Prior systemic chemotherapy, n (%) | 25 (100) |

| Median no. (range) | 5 (2-12) |

| Prior external beam radiation, n (%) | 22 (88) |

| Prior autoSCT, n (%) | 19 (76) |

| Prior alloSCT, n (%) | 25 (100) |

| Prior DLI, n (%) | 6 (24) |

ECOG indicates Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Includes autoSCT, alloSCT, DLI, systemic chemotherapy, and external beam radiation. Conditioning therapy for SCT is not counted as a separate regimen.

Allogeneic SCT.

Patients had received an alloSCT during the years 2000-2009. Before alloSCT, 13 patients (52%) had relapsed/refractory disease. Eleven patients were conditioned with total body or total lymphoid irradiation in conjunction with fludarabine and busulfan (n = 4), fludarabine only (n = 3), fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (n = 2), antithymocyte globulin (n = 1), or alone (n = 1). Seven patients received fludarabine and melphalan alone (n = 4) or in conjunction with antithymocyte globulin (n = 1), busulfan and cytarabine (n = 1), or alemtuzumab and ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE; n = 1). Two patients received busulfan and cyclophosphamide, and 1 patient each received fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; carmustine etoposide, cytarabine melphalan (BEAM); chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, prednisone (ChlVPP); or ICE. Details of the conditioning regimen were unavailable for 1 patient. Donor stem cell sources included 13 matched related, 7 matched unrelated, 3 mismatched unrelated, 1 mismatched related, and 1 unrelated donor with unknown HLA status (Table 2).

Table 2.

AlloSCT history

| N = 25 | |

|---|---|

| Disease state prior to alloSCT, n (%) | |

| Relapsed/refractory disease | 13 (52) |

| Remission | 7 (28) |

| Unknown | 5 (20) |

| Donor status, n (%) | |

| Matched related donor* | 13 (52) |

| Matched unrelated donor* | 7 (28) |

| Mismatched related donor | 1 (4) |

| Mismatched unrelated donor | 3 (12) |

| Unrelated donor with unknown HLA status | 1 (4) |

| Median interval between alloSCT and next subsequent treatment, mo (range) | 12.5 (2-36) |

| Median interval between alloSCT and first dose of brentuximab vedotin, mo (range) | 42 (6-116) |

Considered to be HLA matched at the time of alloSCT.

Sixteen patients (64%) had an objective response after alloSCT, including 14 CRs and 2 PRs. Of the remaining 9 patients, 3 patients (12%) achieved stable disease, 3 had disease progression, and the response was unavailable for 3 patients. All patients subsequently suffered progressive disease after alloSCT with a median time to progression of 12.5 months (range, 2-30). The median interval between alloSCT and first dose of brentuximab vedotin was 42 months (range, 6-116). During this interval, patients had received a median of 3 treatment regimens (range, 0-12). Six patients received at least 1 DLI (range, 1-4); the reasons for DLI were documented as persistent disease for 4 of these patients.

GVHD and infection history.

Between alloSCT and initiation of brentuximab vedotin therapy, 17 patients (68%) were reported to have had acute and/or chronic GVHD. Acute GVHD, reported for 10 patients, was localized to the skin (n = 7), GI tract (n = 5), and liver (n = 3). Chronic GVHD, reported for 10 patients, was localized to the skin (n = 7), oral cavity (n =5), eyes (n = 3), liver (n = 3), and GI tract (1 patient). Thirteen patients (52%) had a history of clinically significant infection(s) during this time period, including 12 patients (48%) with bacterial, viral, or fungal infections. Three patients (12%) had clinical CMV infections, defined as an invasive infection directly related to CMV; 2 of these also had other clinically significant infections.

Most recent prior therapy.

Before enrollment in the initial brentuximab vedotin study, the most recent prior therapies reported for at least 2 patients each were alloSCT (n = 4, 16%); DLI (n = 3, 12%); bendamustine (n = 3, 12%); and mechloroethamine, vincristine. procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP; n = 28%), and lenalidomide and external beam radiation (n = 2, 8% each). Twelve patients (48%) had an objective response to their last prior therapy, including 4 CRs and 8 PRs. Five patients had stable disease, 5 had a best clinical response of disease progression, and the response was unknown for 3 patients. In total, 19 patients (76%) had refractory disease immediately before enrollment, including 17 (68%) who experienced disease progression within 6 months of their most recent prior therapy.

Brentuximab vedotin therapy

Exposure.

Patients began brentuximab vedotin therapy between December 2009 and June 2010, and received a median of 8 cycles (range, 1-16) over a median treatment duration of 27.4 weeks (range, 2.1-53.1). At the time of data cutoff, 6 patients remained on treatment and 19 had discontinued treatment, 8 because of disease progression, 9 because of adverse event, 1 because of investigator decision, and 1 who completed treatment.

Response.

Twenty-four patients were evaluable for response. Of these, 12 (50%) achieved an objective response, including 9 (38%) with CR and 3 (13%) with PR. Ten patients (42%) had stable disease and 2 (8%) had progressive disease. The disease control rate (CR + PR + stable disease) was 92%. The median time to objective response after brentuximab vedotin was 8.1 weeks (range, 5.3-32.0). For the 9 patients with CR, the median time to CR was 10.7 weeks (range, 6.3-32.0). At the time of the data cutoff, just 1 of the 9 patients with CR had experienced disease progression; the duration of response for these 9 patients ranged from 5.3-37.1+ weeks.

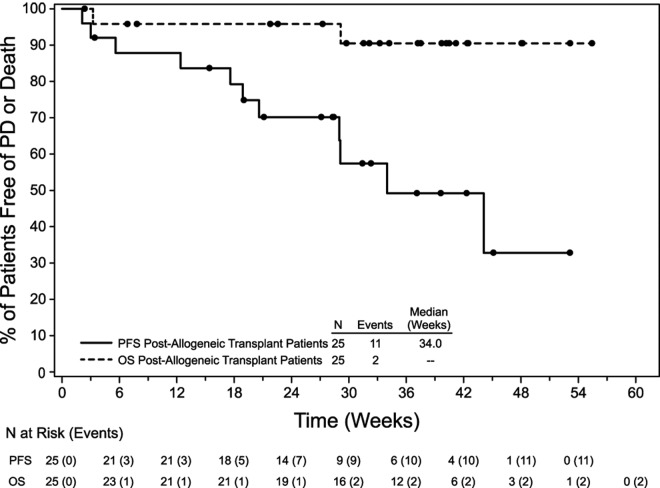

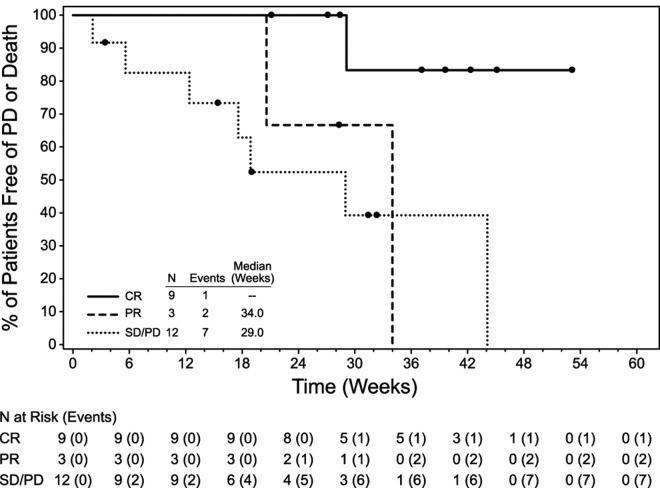

The median PFS for all patients was 7.8 months (range, 0.5-12.2+) and the median overall survival (OS) had not been reached (Figure 1), because 23 patients remained alive at the time of data collection with a median follow up of 34 weeks (range, 2-55). For the 24 patients who were evaluable for response, the median PFS was not reached for patients with CR (n = 9), 34 weeks (range, 20.6-34) for patients with PR (n = 3), and 29 weeks (range, 2.1-44.1) for those who did not have an objective response (n = 12; Figure 2). An example of early response is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

OS and PFS after brentuximab vedotin therapy.

Figure 2.

PFS by response to brentuximab vedotin. Twenty-four patients were evaluable; 1 patient died before the first response assessment. Nine patients had CR, 3 had PR, and 12 had no objective response.

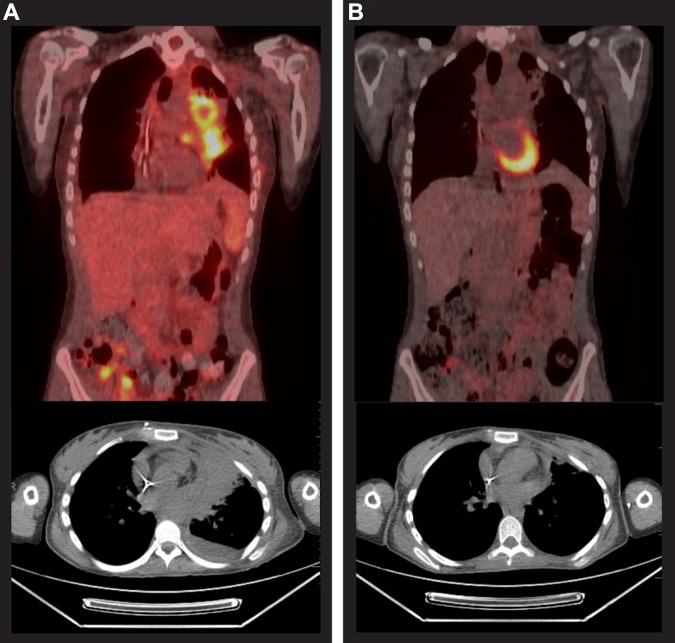

Figure 3.

Case study before and after brentuximab vedotin therapy. Positron emission tomography scans before (A) and after (B) 9 cycles of brentuximab vedotin for a 20-year-old patient who had been diagnosed with HL 3 years earlier. The patient had received 4 cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide followed by external beam radiation that yielded a CR lasting 2 months. She was next treated with 2 cycles of ICE, achieving a PR lasting 1 month. Subsequently, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and doxorubicin (GND), followed by BEAM autoSCT yielded a PR lasting 3 months. She underwent alloSCT for relapsed disease, conditioned with busulfan, fludarabine, and total body irradiation (200 cGy) and had a matched, unrelated donor, but experienced disease progression 4 months after alloSCT. She received her first dose of brentuximab vedotin in December 2009, achieved a PR before the third dose, and a CR was reported after the ninth dose. She completed 16 treatment cycles and remained in CR at the last contact, 6 months after the last dose of brentuximab vedotin.

Univariate analyses were conducted to determine the potential association between patient history and outcome of brentuximab vedotin therapy (Table 3). None of the comparisons reached statistical significance. The sample size did not provide sufficient power for multivariate analysis or for clear interpretation of the data.

Table 3.

Univariate analyses of factors potentially associated with response to brentuximab vedotin

| Factor | Objective response* |

PFS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| Total no. of prior regimens† | 1.07 | 0.87-1.32 | .54 | 0.96 | 0.82-1.13 | .65 |

| Prior autoSCT, yes/no | 0.90 | 0.14-5.65 | .91 | 2.75 | 0.57-13.23 | .21 |

| Prior DLI, yes/no | 2.75 | 0.40-18.87 | .30 | 0.53 | 0.11-2.50 | .42 |

| Prior external beam radiation, yes/no | 2.00 | 0.16-25.40 | .59 | 0.98 | 0.21-4.66 | .98 |

| No. of prior systemic chemotherapy regimens | 1.01 | 0.76-1.33 | .96 | 0.97 | 0.78-1.19 | .74 |

| AlloSCT | ||||||

| Donor source | ||||||

| Matched, related | 4.67 | 0.40-53.95 | .42 | 0.62 | 0.12-3.31 | .58 |

| Matched, unrelated | 5.33 | 0.38-75.77 | .36 | 0.77 | 0.13-4.52 | .77 |

| Other | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Time to disease progression, < 6 mo vs ≥ 6 mo | 0.60 | 0.10-3.50 | .57 | 2.68 | 0.56-12.87 | .22 |

| No. of regimens in the interval between alloSCT and brentuximab vedotin† | 1.05 | 0.85-1.28 | .67 | 0.98 | 0.83-1.15 | .77 |

| Most recent regimen†‡ | ||||||

| Objective response, yes/no | 0.61 | 0.13-2.98 | .54 | 0.50 | 0.13-1.97 | .32 |

| Time to disease progression, < 6 mo vs ≥ 6 mo | 1.13 | 0.20-6.05 | .89 | 1.20 | 0.29-4.95 | .80 |

| Any prior GVHD, yes/no | 0.89 | 0.17-4.78 | .89 | 1.28 | 0.36-4.52 | .70 |

95% CI indicates 95% confidence interval.

Objective response was evaluated using logistical regression and PFS was evaluated using Cox regression. Two-sided P values are presented.

Includes autoSCT, alloSCT, DLI, systemic chemotherapy, and external beam radiation. Conditioning therapy for SCT is not counted as a separate regimen.

Most recent regimen prior to initiation of brentuximab vedotin therapy.

Safety.

All patients experienced at least 1 adverse event. The most common adverse events of any grade were cough, fatigue, and pyrexia (52% each); nausea and peripheral sensory neuropathy (48% each); and dyspnea (40%; Table 4). Eighteen patients (72%) experienced at least 1 adverse event ≥ grade 3; such adverse events reported for more than 2 patients each were neutropenia (n = 6, 24%), anemia (n = 5, 20%), thrombocytopenia (n = 4, 16%), and hyperglycemia (n = 3, 12%). In addition, laboratory abnormalities ≥ grade 3 included low neutrophil counts for 3 more patients and low platelet counts for 2 more patients; these laboratory results were not considered clinically significant by the investigator. No febrile neutropenia or GVHD was reported after initiation of brentuximab vedotin therapy.

Table 4.

Most common treatment-emergent adverse events after brentuximab vedotin therapy

| All grades (N = 25) |

Grade 3 or higher (N = 25) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Cough | 13 | 52 | ||

| Fatigue | 13 | 52 | 2 | 8 |

| Pyrexia | 13 | 52 | 2 | 8 |

| Nausea | 12 | 48 | 1 | 4 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 12 | 48 | 1 | 4 |

| Dyspnea | 10 | 40 | 1 | 4 |

| Diarrhea | 9 | 36 | ||

| Headache | 9 | 36 | ||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 9 | 36 | ||

| Alopecia | 8 | 32 | ||

| Anemia | 7 | 28 | 5 | 20 |

| Back pain | 7 | 28 | 1 | 4 |

| Decreased appetite | 7 | 28 | 1 | 4 |

| Myalgia | 7 | 28 | ||

| Neutropenia | 7 | 28 | 6 | 24 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 7 | 28 | ||

| Vomiting | 7 | 28 | ||

| Arthralgia | 6 | 24 | ||

| Chills | 6 | 24 | ||

| Pruritus | 6 | 24 | ||

| Constipation | 5 | 20 | 1 | 4 |

| Pleural effusion | 5 | 20 | 1 | 4 |

| Pneumonia | 5 | 20 | 2 | 8 |

Includes adverse events of any relationship occurring in at least 20% of patients.

Preexisting peripheral neuropathy and adverse events associated with neuropathy were reported for 11 of 25 patients. Treatment-emergent peripheral neuropathy was reported for 13 patients (52%), including 12 with peripheral sensory neuropathy. Peripheral motor neuropathy was reported for 1 patient. With the exception of 2 grade 3 events (1 peripheral sensory neuropathy and 1 peripheral motor neuropathy), these neuropathy events were grade 1 or 2 in severity. Resolution or improvement in at least some treatment-emergent peripheral neuropathy was reported for 7 of the 13 patients (54%).

Adverse events most frequently reported as being related to study drug were peripheral sensory neuropathy (n = 12, 48%), nausea (n = 7, 28%), alopecia and neutropenia (n = 6, 24% each), and fatigue and vomiting (n = 5, 20% each).

Two patients died, 1 because of intracranial hemorrhage, CMV reactivation, and pancytopenia complicated by Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis and pneumonia and concurrent multisystem organ failure after 1 dose of brentuximab vedotin. The second patient, who withdrew from treatment after 6 doses because of Pseudomonas pneumonia, suffered numerous grade 3 or 4 adverse events after the last dose, including septic shock secondary to the pneumonia and bacteremia, metabolic and respiratory acidosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and gangrene of the toe secondary to septic shock with no evidence of localized infection. This patient died of unknown causes more than 2 months after the last dose.

Nine patients (36%) discontinued brentuximab vedotin treatment because of adverse events, including the one patient described in the preceding paragraph who died on study. Other adverse events that led to treatment discontinuation were sensory neuropathy (n = 5; 1 with grade 3, 3 with grade 2, and 1 with grade 1 events), pneumonia n = 2: 1 with grade 4 and 1 with grade 3 events), and grade 2 elevated creatinine (n = 1).

While on study, 9 patients received transient courses of systemic corticosteroids given primarily for non-GVHD–related adverse events, as treatment for or prophylaxis against infusion reactions, or for management of B-symptoms.

Twenty patients (80%) experienced at least 1 treatment-emergent infection while on study, most commonly upper respiratory tract infection (n = 9). However, these infections were not correlated with clinically significant infections noted between alloSCT and initiation of brentuximab vedotin therapy.

Infectious adverse events of at least grade 3 were reported for 6 patients (24%), including both of the patients who died. Three other patients had grade 3 respiratory infections, 1 patient each with H1N1 influenza pneumonia, presumed Pneumocystis pneumonia, and Pseudomonas and Aspergillus infections of the lungs. The sixth patient had grade 3 Clostridium difficile colitis. Infections for all other patients were grade 1 or 2 in intensity.

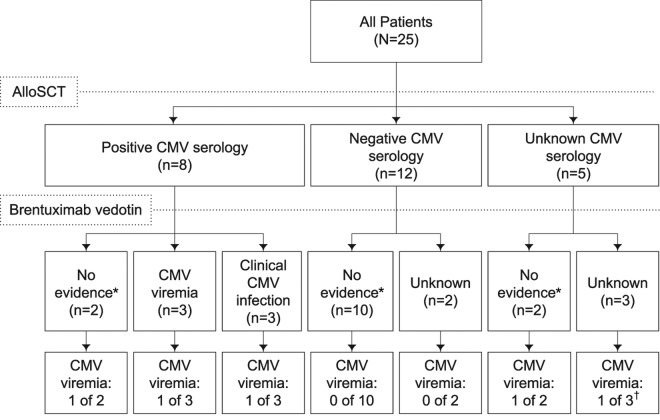

Serial post-baseline CMV surveillance was conducted for 20 patients using PCR. CMV viremia after initiation of brentuximab vedotin therapy was observed in 5 patients. Two of these patients had positive PCR results at the initial test: one died with Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis and pneumonia and multisystem organ failure in the setting of CMV reactivation, and the other remained asymptomatic with intermittent clearance of CMV with antiviral treatment. Another patient, for whom no centralized PCR data are available, had an adverse event of CMV viremia that cleared in 1 week with antiviral treatment. The other 2 patients remained asymptomatic; 1 cleared the virus without antiviral treatment and the other had a single positive PCR result at the last study visit. Among the 4 patients with positive PCR results from study-specific centralized testing, a median of 130 copies/mL (range, 44-920) was observed. Further details for these patients are provided in supplemental Table 2. Several potential risk factors for CMV reactivation were evaluated. CMV viremia after initiation of brentuximab vedotin therapy was observed for 3 of 8 patients (38%) who were seropositive for CMV (Figure 4), although none was clinically significant. Not surprisingly, CMV viremia on study was observed in a higher proportion of patients with a history of CMV viremia or infection (2 of 6 patients, 33%) compared with those without (3 of 19 patients, 16%). No other pattern of predictive factors was evident for CMV history, alloSCT details, or history of GVHD.

Figure 4.

CMV history and CMV viremia after brentuximab vedotin therapy. *No evidence of CMV viremia or clinical infection was reported. CMV viremia is defined as evidence that CMV is active and replicating but has not caused an invasive infection. †Potentially clinically significant.

Laboratory evaluations included routine hematology and serum chemistry tests and assessments of antitherapeutic Abs. At the time of the data cutoff, abnormal laboratory results ≥ grade 3 reported in at least 20% of patients were decreases in neutrophils and lymphocytes (n = 9, 36% each), phosphate (n = 6, 24%), and leukocytes and platelets (n = 5 patients, 20% each). Four patients (16%) developed persistently positive anti–brentuximab vedotin Abs (ie, positive at > 2 post-baseline time points) and 3 patients (12%) developed transiently positive Abs (ie, positive at 1 or 2 post-baseline time points).

Discussion

In the present report, we describe a cohort of 25 patients with CD30+ HL that relapsed after alloSCT. Patients were heavily pretreated, with a median of 9 (range, 5-19) treatment regimens before brentuximab vedotin therapy. Half of the evaluable patients achieved an objective response and 38% attained a CR. The median PFS was 7.8 months and the median OS was not reached, because 23 patients remained alive at the time of data cutoff. Brentuximab vedotin activity in this population was consistent with that observed in the pivotal phase 2 trial of 102 patients with HL,21 although restaging per institutional standard of care in this series could have affected the time-to-response data (Table 5).

Table 5.

Activity and safety of brentuximab vedotin in HL patients after alloSCT compared with HL patients in the pivotal trial

| Post-alloSCT patients (n = 25) | Pivotal trial (n = 102)*21 | |

|---|---|---|

| Measures of response† | ||

| Objective response, % | 50 | 75 |

| CR, % | 38 | 34 |

| Disease control, %‡ | 92 | 96 |

| PFS, mo, median | 7.8 | 5.6 |

| Range | 0.5-12.2+ | NA |

| 95% CI | NA | 5.0-9.0 |

| Time to objective response, wks, median (range)§ | 8.1 (5.3-32) | 5.7 (5.1-56) |

| Patients with CR | ||

| No. (%) of patients | 9 (38) | 35 (34) |

| Time to CR, wks, median (range)§ | 10.7 (6.3-32) | 12 (5.1-56) |

| Safety | ||

| Adverse events of at least grade 3, % | 72 | 55 |

| Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation, % | 36 | 20 |

| Most common treatment-related adverse events, %¶ | ||

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 48 | 42 |

| Nausea | 28 | 35 |

| Alopecia | 24 | 10 |

| Neutropenia | 24 | 19 |

| Fatigue | 20 | 34 |

| Vomiting | 20 | 13 |

95% CI indicates 95% confidence interval; and NA, not available.

Patients who had previously received an alloSCT were excluded from participation in the pivotal trial.

Efficacy results for the post-alloSCT patients in this series (24 efficacy evaluable) were based on investigator judgment, whereas those for the pivotal trial were determined by an independent radiology review facility.

CR + PR + stable disease.

Restaging per institutional standard of care in this series could have affected the time to response data.

Considered by the investigator to be related to brentuximab vedotin.

Placing these data in context of what one might expect in this setting is challenging, but other studies have reported poor outcomes after post-alloSCT relapse, with small differences between OS and PFS.13,14 Decreased survival has been associated with early relapse after alloSCT and with prior autoSCT17,24; unfortunately, the small number of patients in our series did not provide sufficient power to make these types of conclusions. Studies specifically addressing therapeutic maneuvers for relapse after alloSCT are limited, although an 18% response rate to chemotherapy was reported in a small series of HL patients with recurrent disease after alloSCT.24 In contrast, the response rate after DLI with or without prior chemotherapy in a series of 16 patients with HL relapsing after T cell–depleted alloSCT was 56%, although a grade II-IV GVHD rate of 38% was observed.25 With these data in mind, our results remain encouraging.

Adverse events were generally manageable. Not surprisingly, compared with observations from a pivotal phase 2 study,21 that excluded patients with alloSCT, more patients in this cohort had adverse events that led to discontinuation of study treatment or were grade 3 or higher. The most common treatment-related adverse events in this series of patients, however, were generally consistent with those reported for the pivotal trial (Table 5). Clinically significant infections after brentuximab vedotin were not correlated with those noted after alloSCT.

A specific focus of the present investigation was the evaluation of CMV viremia and clinical infection, because we hypothesized that targeting an antigen on activated T cells could further impair cell-mediated immunity in this already high-risk population. CMV was detected in 5 patients and was potentially clinically significant in 1 patient. With the exception of a history of CMV viremia or infection, no pattern of predictive factors was evident for CMV reactivation after treatment with brentuximab vedotin. Comparisons to expected rates of CMV viremia in other post-alloSCT patients receiving antilymphoma therapy are difficult. However, as in this trial, CMV monitoring may be considered, particularly for patients with a positive or unknown history of CMV serology or viremia.

Four patients (16%) in the cohort developed persistently positive anti–brentuximab vedotin Abs, and 3 patients (12%) developed transiently positive Abs. In pivotal studies in patients with HL or systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, approximately 7% of patients developed persistently positive Abs and 30% developed transiently positive Abs.26 The effect of these Abs on safety and efficacy is not known. The apparently higher incidence of persistently positive Abs in this series may be a function of a relatively immunologically replete allogeneic graft compared with observed immune responses in heavily pretreated patients who have not received an alloSCT.

It is important to place the results of the present investigation in context of the broader group of HL patients relapsing after alloSCT. Specifically, candidates were excluded from study participation if they were within 100 days of alloSCT, potentially eliminating the highest-risk patients from this series.17,24 Likewise, no patient in this series was enrolled with the unique post-alloSCT challenge of relapse in the setting of active GVHD. Interestingly, preclinical data imply that targeting CD30 on T cells may abrogate GVHD27,28; therefore, one could hypothesize that brentuximab vedotin could yield a 2-fold benefit for patients with relapse and GVHD, though there are no clinical data to date supporting this premise.

Despite the selection criteria, this series of 25 patients supports the potential clinical benefit of brentuximab vedotin as a therapeutic option for patients suffering relapse of HL after alloSCT, with a 50% objective response rate, a 38% CR rate, and a PFS of 7.8 months. Brentuximab vedotin also exhibited a generally manageable safety profile consistent with results of previous trials, taken in the context of a prior alloSCT. Future studies may be warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of brentuximab vedotin in the setting of post-alloSCT relapse with active GVHD, as well as its potential use as post-transplantation prophylaxis in patients at highest risk for disease recurrence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the studies and the study staff who helped to take care of them; Bess Sorensen and Pamela Levine for statistical guidance; and Roberta Connelly for medical writing assistance. B.S., P.L. and R.C. are under the sponsorship of Seattle Genetics Inc.

Research funding was provided by Seattle Genetics Inc to the institutions of A.K.G., R.R., O.A.O., R.B.B., R.H.A., R.C., S.E.S., M.C., A.R., J.V.M., and J.Z. A.K.G. is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Clinical Scholar.

Footnotes

Presented in part as an oral presentation at the 37th annual meeting of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, April 5, 2011, Paris, France.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K.G., R.R., O.A.O., R.B.B., R.H.A., R.C., S.E.S., M.C., A.R., J.V.M., and J.Z. collected the clinical data; L.E.G. contributed to the conception and design of the 3 clinical trials; A.K.G. and L.E.G. interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors finalized and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.E.G. is employed by and has equity ownership in Seattle Genetics Inc. All other authors received funding from Seattle Genetics Inc to conduct the research. A.K.G., O.A.O., and R.C. acted as consultants; R.R., R.C., and J.Z. were on the speakers' bureau; R.C. and J.Z. received travel expenses; A.K.G. and J.Z. received honoraria; and R.H.A. was a board member for Seattle Genetics Inc. A.K.G. and J.V.M. were on the speakers' bureau, A.K.G. received honoraria, and O.A.O. received research funding and acted as a consultant for Millennium.

Correspondence: Ajay K. Gopal, University of Washington/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, 825 Eastlake Ave E, G3-200, Seattle, WA 98195; e-mail: agopal@u.washington.edu.

References

- 1.Canellos GP, Anderson JR, Propert KJ, et al. Chemotherapy of advanced Hodgkin's disease with MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(21):1478–1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211193272102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diehl V, Franklin J, Pfreundschuh M, et al. Standard and increased-dose BEACOPP chemotherapy compared with COPP-ABVD for advanced Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2386–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Josting A, Franklin J, May M, et al. New prognostic score based on treatment outcome of patients with relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma registered in the database of the German Hodgkin's lymphoma study group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):221–230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin's disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9323):2065–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarella C, Cuttica A, Vitolo U, et al. High-dose sequential chemotherapy and peripheral blood progenitor cell autografting in patients with refractory and/or recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma: a multicenter study of the intergruppo Italiano Linfomi showing prolonged disease free survival in patients treated at first recurrence. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2748–2759. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopal AK, Metcalfe TL, Gooley TA, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for chemoresistant Hodgkin lymphoma: the Seattle experience. Cancer. 2008;113(6):1344–1350. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moskowitz AJ, Yahalom J, Kewalramani T, et al. Pretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116(23):4934–4937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spaepen K, Stroobants S, Dupont P, et al. Prognostic value of pretransplantation positron emission tomography using fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose in patients with aggressive lymphoma treated with high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;102(1):53–59. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sureda A, Constans M, Iriondo A, et al. Prognostic factors affecting long-term outcome after stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin's lymphoma autografted after a first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):625–633. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svoboda J, Andreadis C, Elstrom R, et al. Prognostic value of FDG-PET scan imaging in lymphoma patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(3):211–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burroughs LM, O'Donnell PV, Sandmaier BM, et al. Comparison of outcomes of HLA-matched related, unrelated, or HLA-haploidentical related hematopoietic cell transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(11):1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarina B, Castagna L, Farina L, et al. Allogeneic transplantation improves the overall and progression-free survival of Hodgkin lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous transplantation: a retrospective study based on the time of HLA typing and donor availability. Blood. 2010;115(18):3671–3677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-253856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sureda A, Robinson S, Canals C, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning compared with conventional allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):455–462. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson SP, Sureda A, Canals C, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin's lymphoma: identification of prognostic factors predicting outcome. Haematologica. 2009;94(2):230–238. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armand P, Kim HT, Ho VT, et al. Allogeneic transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning for Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: importance of histology for outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(4):418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corradini P, Dodero A, Farina L, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation following reduced-intensity conditioning can induce durable clinical and molecular remissions in relapsed lymphomas: pre-transplant disease status and histotype heavily influence outcome. Leukemia. 2007;21(11):2316–2323. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ram R, Gooley TA, Maloney DG, et al. Histology and time to progression predict survival for lymphoma recurring after reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(10):1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francisco JA, Cerveny CG, Meyer DL, et al. cAC10-vcMMAE, an anti-CD30-monomethyl auristatin E conjugate with potent and selective antitumor activity. Blood. 2003;102(4):1458–1465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutherland MS, Sanderson RJ, Gordon KA, et al. Lysosomal trafficking and cysteine protease metabolism confer target-specific cytotoxicity by peptide-linked anti-CD30-auristatin conjugates. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(15):10540–10547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Younes A, Bartlett NL, Leonard JP, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) for relapsed CD30-positive lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1812–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2183–2189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(10):1143–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wudhikarn K, Brunstein CG, Bachanova V, Burns LJ, Cao Q, Weisdorf DJ. Relapse of lymphoma after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: management strategies and outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(10):1497–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peggs KS, Hunter A, Chopra R, et al. Clinical evidence of a graft-versus-Hodgkin's-lymphoma effect after reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation. Lancet. 2005;365(9475):1934–1941. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ADCETRIS (brentuximab vedotin) for injection [package insert] Bothell, WA: Seattle Genetics, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blazar BR, Levy RB, Mak TW, et al. CD30/CD30 ligand (CD153) interaction regulates CD4+ T cell-mediated graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2004;173(5):2933–2941. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Elios MM, Romagnani P, Scaletti C, et al. In vivo CD30 expression in human diseases with predominant activation of Th2-like T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61(5):539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.