Abstract

Objectives

To explore the relationships between traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) syndromes and disease severity and prognoses after ischemic stroke, such as neurologic deficits and decline in activities of daily living (ADLs).

Methods

The study included 211 patients who met the inclusion criteria of acute ischemic stroke based on clinical manifestations, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings, and onset of ischemic stroke within 72 hours with clear consciousness. To assess neurologic function and ADLs in patients with different TCM syndromes, the TCM Syndrome Differentiation Diagnostic Criteria for Apoplexy scale (containing assessments of wind, phlegm, blood stasis, fire-heat, qi deficiency, and yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity syndromes) was used within 72 hours of stroke onset, and Western medicine–based National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and Barthel Index (BI) assessments were performed at both admission and discharge.

Results

The most frequent TCM syndromes associated with acute ischemic stroke were wind syndrome, phlegm syndrome, and blood stasis syndrome. Improvement according to the BI at discharge and days of admission were significantly different between patients with and those without fire-heat syndrome. Patients with qi deficiency syndrome had longer hospital stays and worse NIHSS and BI assessments at discharge than patients without qi deficiency syndrome. All the reported differences reached statistical significance.

Conclusions

These results provide evidence that fire-heat syndrome and qi deficiency syndrome are essential elements that can predict short-term prognosis of acute ischemic stroke.

Introduction

Cerebrovascular disease was ranked third among the top 10 leading causes of death in 2010 in Taiwan,1 where the average mortality rate of cerebral vascular disease is 28 cases per day.2 In addition to the high mortality rate, in 2009, the outpatient medical expenditure was NT$6.6 billion, and the inpatient expenditure was NT$6.2 billion,3 which constitutes substantial medical expenses. Strokes damage neurologic function and cause a decline in activities of daily living (ADLs). The need for long-term rehabilitation and medical care imposes a heavy burden on families and society as a whole.

Advances in imaging diagnostics in Western medicine, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have enabled doctors to estimate the lesion site more accurately. The patient's prognosis can then be predicted on the basis of clinical symptoms, together with other forms of clinical evaluation. Much progress has been made in the assessment of prognosis for stroke patients. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) doctors usually evaluate the complicated messages of the body by using four types of examination: inspection, listening and smelling, inquiry, and palpation (namely, “ ”). Because the body's messages are dynamic and able to transform into one another, these messages reflect the comprehensive clinical manifestations of the disease in real time and in a manner that differs depending on the individual, time, and location. Therefore, patients with the same biomedical stroke pathogenesis may present with different TCM syndromes because of individual differences in other conditions.

”). Because the body's messages are dynamic and able to transform into one another, these messages reflect the comprehensive clinical manifestations of the disease in real time and in a manner that differs depending on the individual, time, and location. Therefore, patients with the same biomedical stroke pathogenesis may present with different TCM syndromes because of individual differences in other conditions.

In TCM, strokes are classified into two types: meridian-collateral stroke and viscera-bowel stroke. Meridian-collateral stroke is only moderately severe because the pathogen shows only superficial invasion. The symptoms of this form of stroke are insensitivity of the skin, a feeling of heaviness, and difficultly in performing activities. Viscera-bowel stroke is more severe because the pathogen invades the deeper regions of the body. Patients with this form of stroke lose consciousness and the ability to recognize other people. They may also experience paralysis of the tongue, resulting in dribbling of saliva and a loss of the ability to speak. This study focused on meridian-collateral stroke (i.e., the patients were all conscious and were not receiving intensive care) and used the TCM Syndrome Differentiation Diagnostic Criteria for Apoplexy 4 (TSDDCA) scale (Table 1), the U.S. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale5 (NIHSS), and the Barthel Index6 (BI) assessments to explore the effects of different TCM syndromes on neurologic function and ADLs in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Table 1.

Traditional Chinese Medicine Syndrome Differentiation Diagnostic Criteria for Apoplexy Scale

| TCM syndrome | Item | Acute ischemic stroke–related symptoms and signs | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind syndrome | Onset | Peaked 48 hours | 2 |

| Peaked 24 hours | 4 | ||

| Highly varied conditions | 6 | ||

| Onset reached peak | 8 | ||

| Limbs | Clenched hands or clenched jaw | 3 | |

| Jerking limbs | 5 | ||

| Hypertonicity of the limbs or stiffness of the neck and nape | 7 | ||

| Tongue body | Trembling tongue | 5 | |

| Deviation and trembling of the tongue | 7 | ||

| Eyeball | Eyeball moving about or squinting without blinking | 3 | |

| Normal | 0 | ||

| String-like pulse | Yes | 3 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Dizziness and headache | Dizziness or headache with a pulling sensation | 1 | |

| Dizzy head and vision | 2 | ||

| Fire-heat syndrome | Tongue body | Red tongue | 5 |

| Crimson tongue | 6 | ||

| Tongue fur | Thin yellow fur | 2 | |

| Thick yellow fur | 3 | ||

| Dry fur | 4 | ||

| Gray-black and dry fur | 5 | ||

| Stool | Dry feces that were difficult to evacuate | 2 | |

| Dry feces that were difficult to evacuate for 3 days | 3 | ||

| Dry feces that were difficult to evacuate for more than 5 days | 4 | ||

| Spirit-affect | Vexation and irascibility | 2 | |

| Agitation and restlessness | 3 | ||

| Loss of consciousness and delirious speech | 4 | ||

| Features of face and eyes/breath/odor | Strident voice and rough breathing or red dry lips | 2 | |

| Red face and eyes or hasty breathing and fetid mouth odor | 3 | ||

| Fever | Yes | 3 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Pulse condition | Rapid large forceful pulse or string-like rapid pulse or slippery rapid pulse | 2 | |

| Mouth sensation | Bitter taste in mouth and dry pharynx | 1 | |

| Thirst with affinity for cold things | 2 | ||

| Scant red urine | Yes | 1 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Phlegm syndrome | Phlegm | Sticky drooling at the mouth | 2 |

| Coughing of phlegm or vomiting of phlegm-drool | 4 | ||

| Copious sticky phlegm | 6 | ||

| Snoring with phlegm rale | 8 | ||

| Tongue fur | Slimy or slippery tongue fur | 6 | |

| Thick slimy fur | 8 | ||

| Tongue body | Enlarged tongue | 4 | |

| Enlarged tongue with teeth markings | 6 | ||

| Spirit-affect | Indifferent expression or taciturn | 2 | |

| Dullness of spirit-affect or torpor response or somnolence | 3 | ||

| Pulse condition | Slippery pulse or soggy pulse | 3 | |

| Lethargy | Yes | 1 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Fat and swollen body | Yes | 1 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Blood stasis syndrome | Tongue body | Stagnated, varicose, and bruising sublingual collateral vessels | 4 |

| Dark purple tongue | 5 | ||

| Stasis speckle | 6 | ||

| Stasis macule | 8 | ||

| Purple tongue | 9 | ||

| Headache | Pain of fixed location | 5 | |

| Pain like the stabbing of a needle or pain like the burst | 7 | ||

| Limbs | Limb pain in a fixed location | 5 | |

| Purple nails | 6 | ||

| Facial complexion | Dark lower eyelid | 2 | |

| Dark purple lips | 3 | ||

| Dark purple lips and somber facial complexion | 5 | ||

| Pulse condition | Sunken string-like fine pulse | 1 | |

| sunken string-like slow pulse | 2 | ||

| Rough pulse or bound and intermittent pulse | 3 | ||

| Qi deficiency syndrome | Tongue body | Pale tongue | 3 |

| Enlarged tongue | 4 | ||

| Enlarged with teeth-marked tongue or limp tongue | 5 | ||

| Bearing of the body and voice | Lassitude of spirit and lack of strength or shortage of qi and lazy words | 1 | |

| Timid low voice or forceless coughing sound | 2 | ||

| Fatigue and somnolence | 3 | ||

| Weak snoring | 4 | ||

| Sweating | Sweating easily brought on by exertion | 2 | |

| Resting sweating | 3 | ||

| Incessant cold sweating | 4 | ||

| Stool and urine | Sloppy stool or stool that is first hard and then sloppy | 1 | |

| Involuntary loss of urine | 2 | ||

| Urinary and fecal incontinence | 4 | ||

| Limbs | Swelling of the limbs | 2 | |

| Paralysis and flaccidity of the limbs | 3 | ||

| Limp hands and cold limbs | 4 | ||

| Palpitations | Exertional palpitations | 1 | |

| Palpitations while performing minor activities | 2 | ||

| Resting palpitations | 3 | ||

| Facial complexion | Pale complexion | 1 | |

| Pale and vacuous puffy complexion | 3 | ||

| Pulse condition | Sunken fine pulse or slow moderate pulse or vacuous pulse | 1 | |

| Bound and intermittent pulse | 2 | ||

| Faint pulse | 3 | ||

| Yin deficiency with yang -hyperactivity syndrome | Tongue body | Thin tongue | 3 |

| Thin and red tongue | 4 | ||

| Thin and dry red tongue | 7 | ||

| Thin and dry red cracked tongue | 9 | ||

| Tongue fur | Scant fur or peeling fur | 5 | |

| Smooth bare red without fur tongue | 7 | ||

| Spirit-affect | Vexation and irascibility | 1 | |

| Vexation and sleeplessness | 2 | ||

| Agitated and restless | 3 | ||

| Heat signs | Postmeridian reddening of the cheeks or facial baking heat or heat in the palms and soles | 2 | |

| Dizzy head and vision | Yes | 2 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Night sweating | Yes | 2 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Tinnitus | Yes | 2 | |

| No | 0 | ||

| Dry | Dry throat and mouth or dry eyes or dry stool and scant urine | 2 | |

| Pulse condition | Fine string-like pulse or fine rapid pulse | 1 |

Each syndrome is established when the score is >7 (the sum of the highest scores of the respective diagnostic items).

Materials and Methods

The protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the study hospital (Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board no. 100-2720B). Two hundred and eleven patients were recruited for this prospective study, which ran from July 1, 2004, to December 31, 2006. The patients had been admitted to the Neurology Department at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Linkou, Taiwan, and all met the inclusion criteria described below. The TCM doctors who participated in this study all had more than 10 years of clinical experience and had received short-term training for using the TSDDCA scale. The syndrome diagnoses based on the TSDDCA scale were made within 72 hours of ischemic stroke onset. Western medicine neurologists performed routine examinations, including imaging tests at admission, and completed the NIHSS and BI assessments both at admission and at discharge. The patients received conventional Western medical treatments without TCM intervention.

Inclusion criteria

Patients meeting the following criteria were enrolled: (1) diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke based on clinical manifestations and CT or MRI findings; (2) onset of stroke within 72 hours with clear consciousness; (3) no complications involving other major organs; (4) first-ever stroke or a recurrent stroke with a Rankin scale score of ≤1 before the current stroke; and (5) willingness to receive a TCM syndrome differential diagnosis.

Exclusion criteria

Patients meeting the following criteria were excluded: (1) not meeting the preceding diagnostic or inclusion criteria; (2) complications from sepsis or other infections; and (3) unwillingness to receive a TCM syndrome differential diagnosis.

Assessment scales

The NIHSS was developed by Brott et al.5 in 1989. It includes 15 categories, such as level of consciousness, gaze, visual field deficit, facial palsy, motor ability, sensory ability, ataxia, language, and extinction and inattention. The total score is 42, with higher scores indicating more severely compromised neurologic function. Adams et al.7 used the baseline NIHSS and achieved good prognostic assessment of patients after stroke. Because of its good reliability and validity, this scale has been widely used in the assessment of stroke severity and prognosis. The BI was developed by Barthel and Mahoney6 in 1965. It includes 10 categories, such as help needed with feeding, transferring, grooming, using the toilet, bathing, walking, climbing stairs, or dressing, and the presence or absence of fecal or urinary incontinence. The score range is 0–100, with a higher score indicating better independence in ADL and a lower score indicating more dependence on others. The BI is a more reliable and less subjective disability scale and has been used widely in clinical studies and the prognostic assessment of stroke patients.8–10

Since 1994, the TSDDCA scale has been tested in clinical trials. This scale is based on the TCM syndrome scale from TCM apoplexy experts, and it was developed from a statistical analysis of symptoms and TCM syndromes in acute stroke patients (approximately 3000 cases) combined with clinical epidemiology, computer programs, and other complementary factors.11 In the TSDDCA scale, TCM syndromes associated with stroke have been divided into six principal categories: wind syndrome, fire-heat syndrome, phlegm syndrome, blood stasis syndrome, qi deficiency syndrome, and yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity syndrome.12 The symptoms and physical manifestations that are specific and highly sensitive in TCM syndrome diagnosis were assigned weighted scores. The presence of a TCM syndrome is diagnosed when the individual syndrome's score is >7. The severity level of the syndrome is further divided into mild (score, 7–14), moderate (score, 15–22), and severe (score ≥23), with 30 being the highest score. Since the scale was published in 1994, a total of 31 published papers have evaluated the associations between stroke and the TSDDCA.13 In addition, several masters and doctoral theses have been published using these criteria, such as TCM syndromes and damage to neurologic function,14 TCM syndromes and laboratory results,15 and the association of TCM syndromes with imaging studies.16

Statistical analysis

PASW Statistics (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used to analyze the clinical data. Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean±standard deviation or n (%) for baseline characteristics and TCM syndromes. Independent t-tests were used for continuous variables to compare the difference between TCM syndromes, and the χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was performed to explore the associations of baseline characteristics and TCM syndromes with other prognosis variables, such as the NIHSS and the BI scores and days of hospital stay. Furthermore, the potentially correlated variables with p<0.05 in univariate analysis were entered in the multiple regression models by using the stepwise method. We considered p<0.05 (two-tailed) to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

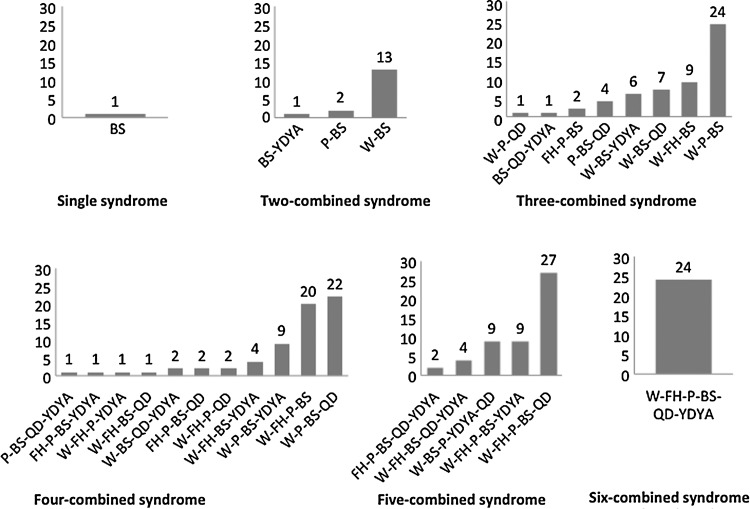

A total of 226 patients met the inclusion criteria after serial selection, and 15 of these declined to undergo the diagnostic assays for stroke syndrome. Regarding the frequency of individual syndromes, the most common syndrome was blood stasis (n=207 [98.1%]), followed by wind syndrome (n=194 [91.9%]), phlegm syndrome (n=162 [76.8%]), qi deficiency (n=109 [51.7%]), fire-heat syndrome (n=108 [51.2%]), and yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity syndrome (n=74 [35.1%]) (Table 2). Coexisting syndromes most commonly occurred as combinations of 4, followed by combinations of 3, in a total of 29 types of syndrome combinations. The most frequent combination was wind-fire heat-phlegm-blood stasis-qi deficiency syndrome (n=27), followed by wind-phlegm-blood stasis syndrome (n=24), and wind-fire heat-phlegm-blood stasis-qi deficiency-yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity syndrome (n=24) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 64.01±12.41 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 140 (66.4) |

| Female | 71 (33.6) |

| Medical history | |

| Hypertension | 155 (73.5) |

| Diabetes | 76 (36.0) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 49 (23.2) |

| Previous stroke | 48 (22.7) |

| Previous TIA | 5 (2.4) |

| Risk factors | |

| Smoking | 81 (38.4) |

| Drinking | 43 (20.4) |

| Stroke-related TCM syndromes | |

| Blood stasis | 207 (98.1) |

| Wind | 194 (91.9) |

| Phlegm | 162 (76.8) |

| Qi deficiency | 109 (51.7) |

| Fire-heat | 108 (51.2) |

| Yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity | 74 (35.1) |

| NIHSS score | |

| Admission | 5.4±3.56 |

| Discharge | 3.98±3.45 |

| BI score | |

| Admission | 65.85±27.01 |

| Discharge | 79.8±24.28 |

| Days of hospital stay | 12.97±10.90 |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) of patients or the mean±standard deviation. BI, Barthel Index; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

FIG. 1.

Traditional Chinese Medicine syndrome combinations in cases of acute ischemic stroke. BS, blood stasis; FH, fire-heat; P, phlegm; QD, qi deficiency; W, wind; YDYA, yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity. Y-axis, number of cases.

The univariate analysis revealed the following: (1) A history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) and fire-heat syndrome influenced the NIHSS score at admission; (2) diabetes mellitus, qi deficiency, and fire-heat syndromes influenced the NIHSS score at discharge; (3) fire-heat syndrome influenced the BI score at admission; (4) hypertension, diabetes mellitus, qi deficiency, and fire-heat syndromes influenced the BI score at discharge; and (5) qi deficiency and fire-heat syndromes influenced the days of hospital stay (Table 3). The potentially correlated variables with p<0.05 in univariate analysis were entered in a multiple regression model by using the stepwise method, which revealed the following results: (1) Diabetes mellitus and qi deficiency syndrome influenced the NIHSS score at discharge; (2) fire-heat syndrome, hypertension, and qi deficiency syndrome influenced the BI score at discharge; and (3) fire-heat and qi deficiency syndromes influenced the duration of hospital stay. More specifically, patients with qi deficiency stayed in the hospital for an average of 3.49 days more than those with no qi deficiency; patients with fire-heat syndrome stayed in the hospital for an average of 2.91 days longer than those with no fire-heat syndrome (Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariate Correlation Between Baseline Characteristics, Traditional Chinese Medicine Syndromes, and Acute Ischemic Stroke Outcome

| |

NIHSS score |

BI score |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Admission | Discharge | Admission | Discharge | Hospital stay |

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Sex (male) | −0.25 (0.5) | −0.14 (0.5) | 7.02 (3.9) | 2.58 (3.5) | 0.45 (1.6) |

| Age (year) | −0.002 (0.02) | 0.004 (0.02) | −0.29 (0.1) | −0.24 (0.1) | −0.03 (0.1) |

| Smoking | −0.47 (0.5) | −0.02 (0.5) | 1.32 (3.8) | 1.70 (3.4) | −1.10 (1.5) |

| Alcohol consumption | −0.70 (0.6) | 0.09 (0.6) | 5.21 (4.6) | −1.02 (4.2) | 0.18 (1.9) |

| Hypertension | 0.10 (0.6) | 0.79 (0.5) | −4.43 (4.2) | −8.31 (3.8)* | 1.37 (1.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.32 (0.5) | 1.27 (0.5)* | −5.14 (3.9) | −7.63 (3.4)* | 2.68 (1.6) |

| Heart disease | 0.62 (0.6) | 0.46 (0.6) | −5.23 (4.4) | −5.16 (4.0) | 2.51 (1.8) |

| Previous stroke | 0.64 (0.6) | 0.70 (0.6) | −3.94 (4.4) | −3.49 (4.0) | 0.14 (1.8) |

| Previous TIA | −3.69 (1.6)* | −2.64 (1.6) | 22.68 (12.2) | 20.61 (10.9) | −6.53 (4.9) |

| TCM syndromes | |||||

| Qi deficiency | 0.49 (0.5) | 1.13 (0.5)* | −3.09 (3.7) | −7.25 (3.3)* | 3.84 (1.5)* |

| Yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity | 0.66 (0.5) | 0.47 (0.5) | −5.27 (3.9) | −2.84 (3.5) | 2.02 (1.6) |

| Phlegm | 0.70 (0.6) | 0.90 (0.6) | −2.48 (4.4) | −4.01 (4.0) | 0.92 (1.8) |

| Blood stasis | −0.10 (1.8) | 1.25 (1.7) | 5.97 (13.7) | −5.22 (12.3) | −2.32 (5.5) |

| Wind | −1.55 (0.9) | −1.63 (0.9) | −3.23 (6.8) | 3.07 (6.2) | −0.73 (2.8) |

| Fire-heat | 0.99 (0.5)* | 1.05 (0.5)* | −9.15 (3.7)* | −11.61 (3.3)** | 3.32 (1.5)* |

Higher NIHSS score indicates more severely compromised neurologic function. Higher BI score indicates better independence in activities of daily living.

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

BI, Barthel Index; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SE, standard error; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table 4.

Multiple Regression Analysis of Acute Ischemic Stroke Outcome

| |

Discharge NIHSS score |

Discharge BI score |

Hospital stay |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient (SE) | p-value | Coefficient (SE) | p-value | Coefficient (SE) | p-value |

| Admission NIHSS score | 0.776 (0.038) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Admission BI score | – | – | 0.660 (0.040) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Hypertension | – | – | −5.148 (2.391) | 0.032 | – | – |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.932 (0.280) | 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Qi deficiency | 0.635 (0.269) | 0.019 | −4.212 (2.121) | 0.048 | 3.493 (1.482) | 0.019 |

| Fire-heat | – | – | −5.211 (2.143) | 0.016 | 2.909 (1.481) | 0.051 |

BI, Barthel Index; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Liu et al.17 reported that TCM syndromes did not influence the short-term prognosis of acute ischemic stroke in a distinct geographic region in Taiwan. Some other studies revealed that older patients at discharge or patients with a history of TIA or stroke had worse prognosis of acute ischemic stroke.18–23 The current study found that fire-heat syndrome and qi deficiency syndrome—rather than sex, age, smoking, drinking, heart disease, stroke, or a history of TIA—significantly and negatively affected neurologic deficits, ADLs, or days of hospital stay.

The etiology and pathogenesis of stroke are multifactorial and complex. This study focused on TCM syndromes in Taiwanese patients with ischemic stroke attack within 72 hours. The TSDDCA scale was used to divide the strokes into six principal syndromes: wind syndrome, fire-heat syndrome, phlegm syndrome, blood stasis syndrome, qi deficiency syndrome, and yin deficiency with yang hyperactivity syndrome. Combinations of four of these syndromes were the most frequent. The total number of syndrome combinations identified was 29, confirming that the manifestations of stroke are complex and variable. This study also found that the most important pathologic products of acute ischemic stroke are wind (91.9%), phlegm (76.8%), and blood stasis (98.1%), findings consistent with those of previous studies.24–27 The most common syndrome of stroke at the acute stage was wind syndrome, and it was usually complicated with phlegm and blood stasis, two major pathologic products of stroke.

Qi deficiency and fire-heat syndromes were not as frequent as wind, phlegm, and blood stasis syndrome, making up 51.7% and 51.2% of the total cases, respectively. However, these conditions might constitute the most important factors to affect the short-term prognosis of acute ischemic stroke. The analysis of fire-heat syndrome in stroke revealed that after Western medical treatment, fire-heat syndrome affected the BI score (5.21 lower than no fire-heat syndrome) but not the NIHSS score at discharge. Moreover, patients with fire-heat syndrome had stayed 2.91 days longer in the hospital than those without. Other studies have also reported that the prognosis of patients with fire-heat syndrome is worse than that of patients without this syndrome.28,29 Some studies revealed that history of hypertension influenced the prognosis of patients with stroke.22,30 The current study found that patients with a history of hypertension had a BI score that was lower by 5.15 at discharge, but no significant differences in the days of hospital stay than those without. Patients with fire-heat syndrome or a history of hypertension had a lower BI score at discharge, and the former had longer hospital stays. This suggested that fire-heat syndrome was a more important prognostic factor than history of hypertension in patients with ischemic stroke.

After treatment with conventional Western medicine, patients with qi deficiency syndrome had longer hospital stays (3.49 days on average) and worse NIHSS and BI scores than those without. This suggests that although qi deficiency syndrome is not a pathogenetic factor or a precondition of stroke at the acute stage, it could be important in the prognostic process. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies. For example, Chen et al.31 reported that the probability of a poor prognosis 90 days after stroke was 1.595 times higher in patients with qi deficiency syndrome within 72 hours of stroke onset than in those without. Jia et al.32 suggested that the more severe the neurologic deficits, the worse the manifestations of qi deficiency in patients with stroke. Some studies revealed that history of diabetes mellitus influenced the prognosis of patients with stroke at discharge, including the extent of neurologic deficit and self-care ability.33,34 The current study found that qi deficiency syndrome had an effect on prognosis in patients with stroke at discharge that was similar to the effect in patients with a history of diabetes mellitus, but it also entailed longer hospital stay. This finding suggested that qi deficiency syndrome was a more important prognostic factor than history of diabetes mellitus in patients with ischemic stroke.

The patients recruited in this study were all from the inpatient unit of a neurology department. Their symptoms were milder than those of the patients in the intensive care unit, who were excluded from this study. Therefore, this study could not explore how the potential mortality rates of more severe cases are associated with the TCM viscera-bowel stroke. A study involving more cases is needed to confirm these results. Future studies should also aim to investigate whether correcting the qi deficiency or fire-heat syndrome in patients with acute ischemic stroke will improve their prognosis.

Conclusions

From a comparative analysis of TCM syndromes, NIHSS scores, BI scores, and hospital length of stay in patients with acute ischemic stroke, this study reveals that fire-heat syndrome and qi deficiency syndrome are essential elements that affect the short-term prognosis of the disease, ultimately facilitating the development of more specific and effective treatment guidelines that translate to better medical care and reduced social costs.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported financially by the Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, under grant CCMP93-RD-019, CCMP94-RD-105, and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou under grant CMRPG33053.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Department of Health, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan) Analysis of leading causes of death, 2010. Jul, 2011. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=11962&class_no=440&level_no=4. [Sep 11;2011 ]. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=11962&class_no=440&level_no=4 . Online document at:

- 2.Department of Health, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan) Daily average number of leading causes of death. Jul, 2011. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=11962&class_no=440&level_no=4. [Sep 11;2011 ]. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=11962&class_no=440&level_no=4 . Online document at:

- 3.Department of Health, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan) Statistical annual report of medical care, National Health Insurance, 2009. Nov, 2011. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2_p02.aspx?class_no=440&now_fod_list_no=11587&level_no=3&doc_no=79126. [Sep 11;2011 ]. http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2_p02.aspx?class_no=440&now_fod_list_no=11587&level_no=3&doc_no=79126 . Online document at:

- 4.Ren ZL. Wang SD. Gao Y. Criterion for diagnosis and differentiation of syndromes of stroke (On trial) J Beijing Univ Trad Chinese Med. 1994;17:64–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brott T. Adams HP., Jr Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahoney FI. Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams HP., Jr Davis HP. Leira EC, et al. Baseline NIH stroke scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: a report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) Neurology. 1999;53:126–131. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Olhaberriague L. Litvan I. Mitsias P, et al. A reappraisal of reliability and validity studies in stroke. Stroke. 1996;27:2331–2336. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.12.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe CD. Taub NA. Woodrow EJ, et al. Assessment of scales of disability and handicap for stroke patients. Stroke. 1991;22:1242–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulter G. Steen C. De Keyser J. Use of the Barthel Index and Modified Rankin Scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 1999;30:1538–1541. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C. Gao Y. Recent situation of application about standards of syndrome-differentiated diagnosis in Apoplexy. Tianjin J Trad Chinese Med. 2007;24:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Manila, Phillippines: WHO Western Pacific Regional Office; 2007. WHO international standard terminologies on traditional medicine in the western pacific region. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai FK. Lin CH. Chang YJ, et al. Analysis of TCM syndromes of ischemic stroke patients at acute stage. Chinese Med J. 2011;22:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H. Thesis for PhD Degree. Beijing: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2006. Correlation between syndrome changes and neurological parafunction of ischemia stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren Y. Thesis for Master Degree. Beijing: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2007. Correlation between whole blood platelet aggregation and syndrome of acute stage of stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong HZ. Thesis for Master Degree. Beijing: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2007. To explore the correlation between the area of stroke lesion by MRI and the characteristic syndrome of ischemic stroke within 72 hours. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu CH. Tang NI. Li TC, et al. The Chinese medicine pattern and clinical severity of patients with acute stage cerebral infarct in Taiwan. Mid-Taiwan J Med. 2006;11:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalra L. Does age affect benefits of stroke unit rehabilitation? Stroke. 1994;25:346–351. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama H. Jørgensen HS. Raaschou HO, et al. The influence of age on stroke outcome: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 1994;25:808–813. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.4.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wade DT. Hewer RL. Stroke: associations with age, sex and side of weakness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:540–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson TP. Bourestom NC. Greenberg FR, et al. Predictive factors in stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1974;55:545–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jørgensen HS. Nakayama H. Reith J, et al. Stroke recurrence: predictors, severity and prognosis: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Neurology. 1997;48:891–895. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muuronen A. Kaste M. Outcome of 314 patient with transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1982;13:24–31. doi: 10.1161/01.str.13.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang WX. Huang PX. Liu MC, et al. A study on the distributions of TCM syndromes in patients with acute stroke. J Guangzhou Univ Trad Chinese Med. 1997;14:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin JX. Feng Y. Chen JL, et al. Analysis of the distribution of TCM syndromes of apoplexy at acute stage. J Beijing Univ Trad Chinese Med. 2004;27:83–85. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang SD. Ren ZL. Du MH, et al. The clinical study on the syndromes of the early stroke. China J Trad Chinese Med Pharm. 1996;11:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang YL. Zheng H. Liu WN. Analysis of the syndromes of apoplexy at acute stage. J Emerg Trad Chinese Med. 1995;4:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu K. Thesis for Master Degree. Beijing: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2006. To investigate the factors effect on the prognosis of acute stage of ischemic stroke and its characteristic syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin JX. Feng Y. Gao Y, et al. Study of the correlation between TCM fire-heat syndrome and modern medical diagnostic criteria of apoplexy at the acute stage. J Beijing Univ Trad Chinese Med. 2004;27:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabkin SW. Mathewson FAL. Tate RB. The relation of blood pressure to stroke prognosis. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:15–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y. Thesis for Master Degree. Beijing: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2010. To investigate the correlation between syndrome elements and the prognosis at acute stage of ischemic stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia N. Cai YF. Bai XX, et al. The clinical investigation of the initial characteristic syndrome in 118 patients with acute stage of ischemic stroke. J New Chinese Med. 2008;40:63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matz K. Keresztes K. Tatschl C, et al. Disorders of glucose metabolism in acute stroke patients: an underrecognized problem. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:792–797. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Megherbi SE. Milan C. Minier D. Association between diabetes and stroke subtype on survival and functional outcome 3 months after stroke: data from the European BIOMED Stroke Project. Stroke. 2003;34:688–694. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000057975.15221.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]