Abstract

Objective

To investigate potential violations of patient confidentiality or other breaches of medical ethics committed by physicians and medical students active on the social networking site Twitter.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

The social networking site Twitter (Swedish-speaking users, n=298819).

Population

Physicians and medical students (Swedish-speaking users, n=237) active on the social networking site Twitter between July 2007 and March 2012.

Main outcome measure

Postings that reflect unprofessional behaviour and ethical breaches among physicians and medical students.

Results

In all, 237 Twitter accounts were established as held by physicians and medical students and a total of 13 780 tweets were analysed by content. In all, 276 (1.9%) tweets were labelled as ‘unprofessional’. Among these, 26 (0.2%) tweets written by 15 (6.3%) physicians and medical students included information that could violate patient privacy. No information on the personal ID number or names was disclosed, but parts of the patient documentation or otherwise specific indicatory information on patients were found. Unprofessional tweets were more common among users writing under a pseudonym and among medical students.

Conclusions

In this study of physicians and medical students on Twitter, we observed potential violations of patient privacy and other breaches of medical ethics. Our findings underline that every physician and medical student has to consider his or her presence on social networking sites. It remains to be investigated if the introduction of social networking site guidelines for medical professionals will improve awareness.

Keywords: Medical Education & Training, Epidemiology, Medical Ethics, Statistics & Research Methods, Health informatics < Biotechnology & Bioinformatics

Article summary.

Article focus

The aim of this study was to investigate potential violations of patient confidentiality or other breaches of medical ethics committed by physicians and medical students active on the social networking site Twitter.

It remains to be investigated if the introduction of social networking site guidelines for medical professionals will have an effect on physician and medical student behaviour on social networking sites.

Key messages

We observed breaches of medical ethics, including potential violations of patient privacy. No patients were named or revealed through personal ID numbers, but specific patient situations and characteristics were described.

In our study, 91.1% of physicians and medical students stated their full name and many appeared with a self-identifying image. This finding was somewhat unexpected, as Twitter demands no personal information in return for its services.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study is its design, in which we aimed at including the entire population of Swedish-speaking self-identified physicians and medical students on Twitter. Up to 100 tweets per user were analysed, providing a thorough insight into users’ activity.

A limitation is that the study population consists of self-identified physicians and medical students. Some accounts investigated might be held by non-physicians, for some reason appearing as physicians or as medical students. It seems unlikely that this might alter the results since each account was assessed within the research group.

Introduction

Social networking sites enable internet users to connect, access user profiles and send notes such as emails or instant messages.1 In October 2012, the largest social networking site Facebook reported over one billion active users.2

Physician participation on social networking sites is a matter of increasing interest. Particular attention has been paid to potential breaches of patient confidentiality, and the need for ethical guidelines has been highlighted.3–6 However, when used correctly and with care, participation on social networking sites might help physicians and medical students to disseminate correct and evidence-based information.7

Twitter (http://www.twitter.com) is a popular, free-of-charge internet application. In December 2012, it had an estimated 200 million active users and is one of the top-ranking social networking sites on the internet.8 Twitter permits its users to write messages (‘tweets’) for others to read. Tweets are limited to 140 characters and may contain text, links or photos. The default setting is that user information and tweets may be viewed, indexed, searched or archived by anyone. Tweets and user information are stored in an open database.

In 2011, Chretien et al published a study in JAMA in which they reviewed tweets written by a selected group of 260 English-speaking physicians, all having a followers’ count of 500 or more. Evidence of ethical breaches and unprofessional behaviour was uncovered and potential violations of patient confidentiality were found. Three per cent of the investigated tweets were categorised as unprofessional.9

Since 2010, when their data were collected, the number of Twitter users has increased dramatically. It is reasonable to assume that the presence of physicians and medical professionals on Twitter has increased as well. In this study, the objective was to investigate if unethical or unprofessional online behaviour had occurred in a population-based sample of Swedish-speaking physicians and medical students on Twitter.

Method

In April 2012, account information of Twitter users writing in Swedish was collected (described in more detail on www.twittercensus.se).

Data were retrieved from the open Twitter database (api.twitter.com) and included information on Swedish-speaking users active within the range of network launch in 2006 up to the time of data collection. To begin with, the database was seeded with accounts known to be Swedish. All accounts being followed by/following any of these accounts were retrieved and analysed. Swedish tweets were identified through the open source library Pear LanguageDetect.10 The language identification software recognises specific three letter combinations, which appear with a certain frequency in any given language.11

For every account established to be Swedish, all followers were yet again retrieved and analysed. Non-Swedish speaking followers and followers without tweets were excluded. Also excluded were ‘protected’ accounts (ie, tweets made publicly unavailable through privacy settings).

Retrieved account information from these accounts contained user name, tweets, joining date, biography and recorded name.

Study population

In all, 298 819 accounts were recognised as Swedish. Using keywords associated with physicians and medical students, we generated a gross list of accounts (n=1097) having one or more of the predefined keywords in its user biography. Keywords were established on the basis of general terminology as well as the Swedish National Board of Health's list of physician specialties (see online supplementary appendix 1).

After manual assessment of the gross list of accounts, non-physician users (eg, nurses or biomedical engineers), mock accounts or accounts used solely for one-way communication (eg, automatically generated by news feeds) (n=860) were omitted.

The net list of Swedish physicians and medical students compiled 237 user accounts. We chose to address these accounts as held by ‘self-defined’ physicians or medical students, since neither names nor any other information have been controlled in any central registry of Swedish physicians and medical students.

From these 237 accounts, the 100 most recent tweets per account were analysed (n=13780). For accounts with less than 100 tweets, all available tweets were included.

Resent tweets (‘retweets’) without comments were automatically removed without prior analysis.

Categorisation of tweets

The 2009 imprint of the Swedish Medical Association's Code of Ethics was used as guidance when reviewing and categorising tweets based on content12 (see online supplementary appendix 2).

In a first step, tweets were categorised as either ‘not health-care related’ (eg, greeting phrases, chit-chat or links to news articles) ‘health-care related’ (eg, information on clinical guidelines, health subjects or links to medical articles). In the second step, the ‘not health care-related’ tweets were reviewed and each tweet was categorised as either ‘neutral’ or ‘unprofessional’. ‘Unprofessional’ tweets narrated phenomena such as drunkenness, hangovers or severe profanity.

In the third step, the ‘health-care related’ category was reviewed. Tweets were categorised as either ‘neutral’ or ‘unprofessional’. The ‘unprofessional’ tweets narrated, for example, off-label self-medication with prescription drugs, lamented patient behaviour or contained potential violations of patient privacy.

All tweets coded as ‘unprofessional’ were independently reviewed by two of the authors (AB and SJ) and the final list was adopted with consensus. Tweets that were not considered ‘unprofessional’ by both parties were recoded as ‘neutral’.

Statistical methods

Data are presented as numbers and proportions, or median and IQR. χ2 test was used to test for differences in proportions. Excel for Mac 2011, V.14.3.2, was used for analyses.

Results

In all, 237 Twitter accounts were established as held by physicians and medical students. Of these, 216 (91.1%) presented with first and last names. Ninety-one (38.4%) users declared themselves as medical students, 10 (4.2%) were in internship training programmes and the remaining 136 (57.4%) physicians in various other positions.

The number of tweets per user ranged from 1 to 14 195 since the joining date. The median number of tweets per user was 81 (IQR 17–414). Seventy users (29.5%) had posted more than one tweet every day on average.

The number of followers per account ranged from 0 to 2439 (median 24 (IQR 8–71)). The numbers of accounts followed by each physician and medical student Twitter user ranged between 0 and 2349 (median 55 (IQR 19–119)). The oldest tweet reviewed was posted in July 2007, the most recent in March 2012.

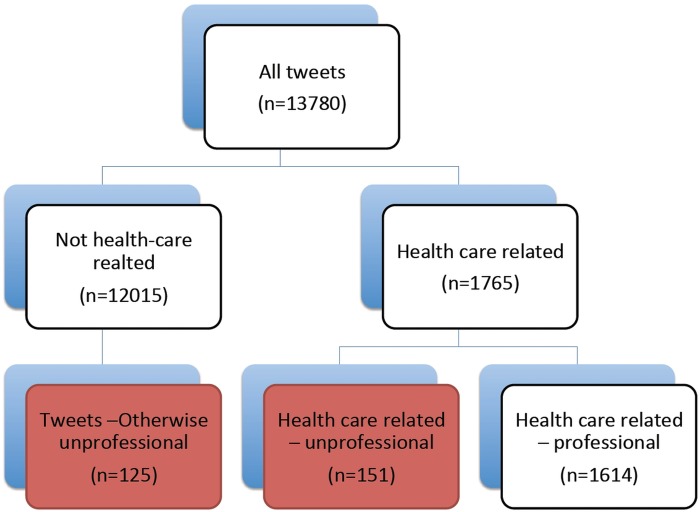

Manual content analysis was performed of 13 780 tweets (figure 1). Of these, 13% were categorised as ‘health-care related’ and 87% were classified as ‘not health-care related’. In total, 276 (1.9%) of tweets were labelled as ‘unprofessional’. Among the healthcare-related tweets, 151 (1.0% of all tweets; 8.6% of the healthcare-related tweets) tweets were categorised as ‘unprofessional’ and of these, 26 (0.2% of all tweets) included information that potentially violated patient privacy. In all, 15 users committed potential privacy violations (6.3%). No tweets included information on personal ID number, but parts of patient documentation or otherwise specific indicatory information on a certain individual were found.

Figure 1.

Subdivision and categorisation of tweets. Up to 100 tweets per user were analysed, amounting to a total of 13 780. As a first step, each was categorised as ‘health-care related’ (1765) or ‘not health-care related’ (12 015). In the ‘not health-care related’ category, 125 tweets were considered unprofessional. These related to drunkenness, hangovers, severe profanity, sexual content or potential illegal activities. In the ‘health-care related’ category, 151 tweets were deemed unprofessional, recounting self-medication, engaging in consultation-like discussions with other users of Twitter, expressing dissatisfaction with the situation at work or upcoming working shift. Among these, 26 tweets described potential breaches of patient confidentiality.

Among the non-healthcare-related tweets, 125 (0.9% of all tweets; 10.4% of the not healthcare-related tweets) were deemed unprofessional, typically including severe profanity, sexual content or heavy drinking.

At least one unprofessional tweet was more commonly found among medical students as compared to physicians, 48 of 91 (53%) vs 47 of 146 (32%; p=0.003).

Unprofessionalism was also more common among users writing under pseudonyms compared to users writing under recorded names. Fourteen of 21 users (67%) writing under pseudonyms wrote at least one unprofessional tweet, and among users with recorded names the corresponding proportion was 81 of 216 users (38%) (p=0.02). When comparing unprofessional tweets between users using pseudonyms or recorded names, the proportion of unprofessional tweets was 71 of 1875 tweets (3.8%) and 205 of 11905 (1.7%), respectively (p<0.001).

Discussion

In our analysis of Twitter content produced by Swedish-speaking physicians and medical students, we observed breaches of medical ethics and potential violations of patient privacy. The results are in line with what was found in 2011 by Chretien et al,3 although our studies are not directly comparable due to differences in study design.

Patient confidentiality is regulated by law, and must be abided by all licensed healthcare personnel.13 No patients could be directly identified (eg, presented with names or personal ID numbers), but specific patient situations and characteristics were described. We argue that such tweets could represent violations against current guidelines and laws for patient privacy and integrity.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is its design, in which we aimed at including the entire population of Swedish-speaking self-identified physicians or medical students on Twitter. Up to 100 tweets per user were analysed, providing a thorough insight into user activity. Moreover, the consensus approach with two observers led to a conservative estimate of unprofessionalism and a reduced risk of misclassification.

A limitation is that the study population consists of self-identified physicians and medical students. It cannot be ruled out that some accounts investigated were held by non-physicians that for some reasons appear as physicians or as medical students. However, when establishing the study group, we came to the conclusion that self-identification was the inclusion criterion that seemed the most straightforward and appropriate. Also, it allows for the study to be easily repeated. It is also likely that other users of Twitter perceive a user who proclaims himself or herself a physician or medical student as such, and any ethical breaches might therefore be considered as made by a physician or medical student.

Comparisons with other studies

An asset in relation to the 2011 study by Chretien et al on 260 English-speaking physician Twitter users with more than 500 followers is that our approach is (1) population based and (2) aims to investigate all Swedish-speaking physician users, including medical students. We believe that selection bias may be a limitation of the study by Chretien et al. It is quite likely that doctors with many followers on Twitter are more experienced users of social media and therefore behave more professionally. In our material, only a few accounts had more than 500 followers. A population-based approach including all doctors on Twitter is likely to give a more reliable estimate of unprofessionalism. In addition, we reviewed 100 tweets per user compared to 20 tweets per user in the study by Chretien et al. We believe that by analysing more tweets per user from a population-based cohort, it is likely that we will gain a more representative sample of tweets.

On Facebook, physicians and medical students often use their full name.14 15 This is not unexpected, since Facebook requires users to state their full name. In our study, 91.1% of the physicians and medical students stated their full name. Many also appeared with a self-identifying image. Twitter demands no personal information in return for its services, and therefore this finding is somewhat surprising.

Virtual colleagues, virtually colleagues

The emergence of social networking sites on the internet has changed the way medical professionals communicate. Social networking sites are here to stay and it is important that medical professionals adapt to this changing communication landscape.

Whereas some content is clearly unprofessional (eg, patient privacy breaches), others are of a more ambiguous nature. Expressions of profanity, sexism or heavy alcohol use on social networking sites might not be judged as ‘unprofessional’ since its content may not be clearly work-related. It might be argued that the content is written ‘off duty’ and should be considered private expressions. However, since our study group chose to state occupation (often together with first and last names), it will inevitably affect how civilian users perceive them. In studies, it has been demonstrated that illusory anonymity might increase morally questionable behaviour.16 In analogy, it could be reasoned that the perceived anonymity for a Twitter user might lower the threshold for unprofessional behaviour. This is supported by our finding that users writing under pseudonyms more frequently tweet unprofessionally.

Twitter is a social networking site that invites its users to interact, effectively lowering the threshold to engage in conversation with fellow Twitter users. It is our own experience that the physician and medical student users in our study interact frequently with their ‘virtual colleagues’, many of whom they have probably never met face-to-face. Sharing the experience of being a physician or a medical student, they sometimes engage in a conversation of a sort similar to one that might have taken place in a staffroom in a clinic. Yet, the perceived sense of having a conversation with a colleague is deceiving. In fact, what is written will not only be read by colleagues, but might also be read by an immeasurable number of Twitter users and be reshared throughout the network and beyond. By posting a message on Twitter, the user readily loses all control of how the messages will be shared, resent and interpreted.

Social networking guidelines and policy implications

Physician jargon is at times harsh; it might even be perceived as callous. For junior physicians or medical students, it may not be obvious what is and what is not suitable content on social networking sites. An unguarded tweet might have unintended consequences. Although the overall proportion of accounts with unprofessional tweets was high, our data suggest that unprofessionalism may be more common among medical students than among physicians. As previously suggested, we also believe that peer assessment might offer valuable feedback for physicians or medical students behaving unprofessionally.17 We do not see the need for more anonymity or tighter security settings. Rather, we encourage physicians or medical students to use social networking sites with greater care. As has been argued previously, physicians and medical students need to understand that professionalism and sharing private information publicly are intertwined and to always ‘think before you tweet’.18

In 2010, the American Medical Association published guidelines on online professionalism in the association's Code of Medical Ethics.19 In a study from 2011, pharmacy students strengthened Facebook security settings to make content less visible after the introduction of a social media policy.20 In November 2012, the Swedish Medical Association and the Swedish Society of Medicine issued joint advice for physicians active in social networks.21 Whether this advice will affect physician use of Twitter would have to be investigated in future studies.

Conclusion

In a study of physicians and medical students on Twitter, we observed potential violations of patient privacy and other breaches of medical ethics. Our findings underline that every physician and medical student has to consider his or her presence on social networking sites. It remains to be investigated if the introduction of social networking site guidelines for medical professionals will improve awareness.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AB designed the study, collected and analysed the data and drafted the article. SJ participated in the study design, interpretation of the data and drafting of the article. EA contributed to the conception of the study, revised the article for important intellectual content and approved the final version. NL participated in interpretation of the data, revised the article for important intellectual content and approved the final version. AKEB is the principal researcher responsible for the ethics approval; and participated in the analyses and interpretation of the data and also in the drafting of the article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the regional ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (Reference: 2012-1672-31/5).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: In accordance with our ethics approval, the publication of the results of this study may only take place in such a way that the identities of individuals are not divulged. Our database contains personal data and cannot be shared. Software for language identification is available online: http://pear.php.net/package/Text_LanguageDetect.

References

- 1.Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horizons 2010;53:59–68 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroeder S.2012. Facebook hits one billion active users. Mashable [Internet] [cited 5 Feb 2013]. http://mashable.com/2012/10/04/facebook-one-billion/

- 3.Chretien K, Greysen S, Chretien J-P, et al. Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students. JAMA 2009;302:1309–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guseh II JS, Brendel RW, Brendel DH. Medical professionalism in the age of online social networking. J Med Ethics 2009;35:584–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson L, Black E, Duff W, et al. Protected health information on social networking sites: ethical and legal considerations. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicans. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:777–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dizon DS, Graham D, Thompson MA, et al. Practical guidance: the use of social media in oncology practice. J Oncol Pract 2012;8:e114–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiegerman S.2012. Twitter now has more than 200 million monthly active users. Mashable [Internet] [cited Jan 22, 2013]. http://mashable.com/2012/12/18/twitter-200-million-active-users/

- 9.Chretien K, Azar J, Kind T. Physicians on Twitter. JAMA 2011;305:566–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pisarro N. Pear LanguageDetect [0.3.0, release 2012-01-16] [Internet Software]. http://pear.php.net/package/Text_LanguageDetect.

- 11.Cavnar W, Trenkle J. N-gram-based text categorization. In Proceedings of SDAIR-94, 3rd Annual Symposium on Document Analysis and Information Retrieval. 1994:161–75 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swedish Medical Association [Internet] Läkarförbundets etiska riktlinjer; 2009. [last updated 2011-08-08][cited 11 Feb 2013]. http://www.slf.se/Etikochansvar/Etik/Lakarforbundets-etiska-regler/

- 13.Swedish statutes, SFS 2009:400. [Internet]. Updated: SFS 2012:956 [last changed: 5 Feb 2013.] [Cited 5 Mar 2013]. www.notisum.se: http://www.notisum.se/Pub/Doc.aspx?url=/rnp/sls/lag/20090400.htm.

- 14.Moubarak G, Guiot A, Benhamou Y, et al. Facebook activity of residents and fellows and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship. J Med Ethics 2011;37:101–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner J, O'Sullivan H. Facebook and the professional behaviours of undergraduate medical students. Clin Teach 2010;7:112–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong CB, Bohns VK, Gino F. Good lamps are the best police: darkness increases dishonesty and self-interested behavior. Psychol Sci 2010;21:311–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold L, Shue CK, Kritt B, et al. Medical students’ views on peer assessment of professionalism. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:819–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson LA, Dawson K, Ferdig R, et al. The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:954–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Medical Association AMA's Code of Medical Ethics [Internet] 2010. [cited 26 Jan 2013]. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics.page

- 20.Williams J, Feild C, James K. The effects of a social media policy on pharmacy students’ facebook security settings. Am J Pharm Educ 2011;75:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swedish Medical Association and the Swedish Society of Medicine. 2012. Sveriges Läkarförbundets och Svenska läkaresällskapets policydokument om användning av sociala medier. [cited 14 Feb 2013]. http://www.slf.se/upload/Lakarforbundet/Trycksaker/R%C3%A5d%20till%20l%C3%A4kare_socialamedier_webbversion.pdf den 26 Jan 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.