Abstract

Objective

To assess factors related to use and non-use of a sophisticated interactive preventive health record (IPHR) designed to promote uptake of 18 recommended clinical preventive services; little is known about how patients want to use or be engaged by such advanced information tools.

Design

Descriptive and interpretive qualitative analysis of transcripts and field notes from focus groups of the IPHR users and of patients who were invited but did not use the IPHR (non-users). Grounded theory techniques were then applied via an editing approach for key emergent themes.

Setting

Primary care patients in eight practices of the Virginia Ambulatory Care Outcomes Research Network (ACORN).

Participants

Three focus groups involved a total of 14 IPHR users and two groups of non-users totalled 14 participants.

Outcomes/results

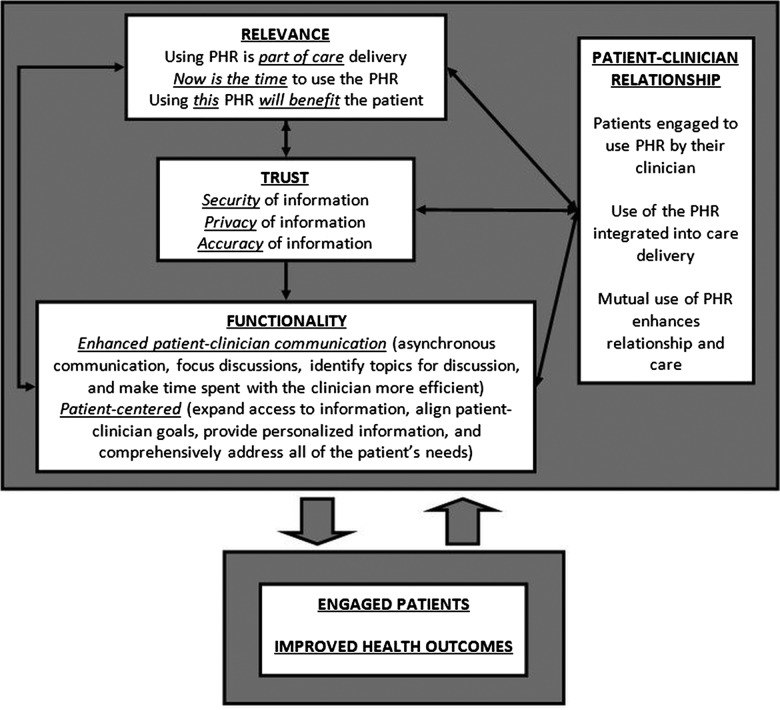

For themes identified (relevance, trust and functionality) participants indicated that endorsement and use of the IPHR by their personal clinician was vital. In particular, participants’ comments linked the IPHR use to: (1) integrating the IPHR into current care, (2) promoting effective patient–clinician encounters and communication and (3) their confidence in the accuracy, security and privacy of the information.

Conclusions

In addition to patients’ stated desires for advanced functionality and information accuracy and privacy, successful adoption of the IPHRs by primary care patients depends on such technology's relevance, and on its promotion via integration with primary care practices’ processes and the patient–clinician relationship. Accordingly, models of technological success and adoption, when applied to primary care, may need to include the patient–clinician relationship and practice workflow. These findings are important for healthcare providers, the information technology industry and policymakers who share an interest in encouraging patients to use personal health records.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00589173

Keywords: Primary Care, Preventive Medicine, Qualitative Research

Article summary.

Article focus

What are necessary elements for patient engagement in advanced interactive personal health records?

Key messages

Engagement in an interactive prevention health record (IPHR) is related to integration into current care and the patient–clinician relationship.

Models of technology success and acceptance may warrant modification when applied to primary care use of the IPHRs.

Strengths and limitations of this study

An advanced IPHR shown to increase use of preventive services was employed for the study.

The sample was drawn from northern Virginia, USA. Other locales may have different the IPHR needs and require different strategies to engage patients in the IPHR use.

Most participants had ongoing established relationships with their clinician.

Background

The concept of patient-centred care is not new to medicine.1 2 Decades ago, research demonstrated that engaging patients in their care improves patient satisfaction, quality of care and clinical outcomes.3 4 Recently, national movements aimed at transforming healthcare have formally defined, incentivised and institutionalised patient-centred care. The goals of the Patient-Centered Medical Home espouse these principles.5 6 State and national legislation combined with payer initiatives now encourage and support practices to provide patient-centred care.7 8 The national Meaningful Use Roadmap defines patient and family engagement from a patient perspective as ‘actions we must take over time to obtain the greatest benefit from the healthcare services available to us’, further stating that engagement is desirable and necessary for health information systems.5 9 10

Personal health records (PHRs) are an important resource to help practices provide patient-centred care. Currently, the most common functions performed by PHRs include record keeping, secure messaging, appointment scheduling and bill payment.11 Yet, other PHR features could help facilitate patient engagement in their medical care, including use of plain English depictions of clinical data, motivational messages to seek needed care, educational resources, decision aids and resources and tools to support and guide care.12 13

While electronic PHRs have been available for more than a decade and have wide adoption in some large healthcare organisations,14 15 they are used by only a fraction of Americans, and practices struggle to promote patient adoption.11–23 One possible reason for poor PHR uptake is that many systems lack integration into the care delivery system, including clinicians’ EMRs.13 17 21 Tang and Lee suggest that integrated PHRs could provide patients better access to laboratory and other data, as well as communication with their cliniciani. This, they posit, will facilitate ‘the type of physician–patient relationship that will improve health.’19

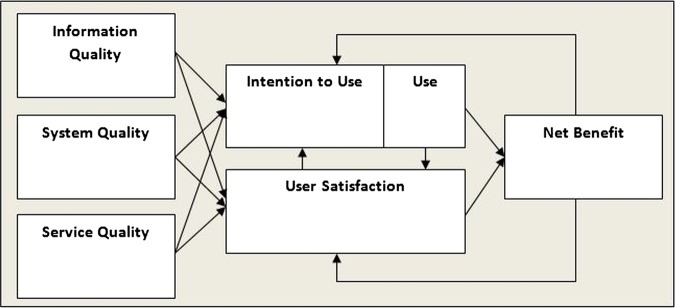

To date PHR adoption has typically been approached from clinician23 24 or technology-driven24 25 perspectives, operating under the assumption that increasing the number of clinicians using an EMR will increase the number of patients who use a PHR.23 National survey data suggest and others have advocated that patient PHR adoption would better increased by designing and promoting more patient-centred PHRs that consider patients’ individual and cultural issues as well as promote the patient–clinician relationship.12 22 Similarly, even widely cited models of technology promotion, such as the Model of Information Systems Success (MISS)26 and the Technology Acceptance Model,27 have often been applied to healthcare with little patient or clinician perspective28 29 or by purposively eschewing ‘person-to-person trust’ in evaluating such models.25 To our knowledge, no one has evaluated these models in a patient-centred PHR shown to improve patient outcomes.

In 2007, we created an IPHR that was designed with greater functionality to engage and activate patients in their preventive care. Details about the design of the IPHR,30 findings from a randomised controlled trial demonstrating that the IPHR significantly improved preventive care31 and a how-to-guide showing practices how they can use their PHRs to better promote preventive care, have been previously published.32 The IPHR was not meant to be a complete PHR or to replace commercial systems. It did not contain common administrative functions, such as secure messaging, appointment scheduling or bill paying. Rather, the IPHR was meant to be patient-centred, action-oriented, prevention-focused application that functioned within existing PHRs. Briefly, the IPHR combined a patient's clinical information from his/her clinician's EMR (eg, history, dates and results) with patient-reported information (eg, family history and health behaviours). The IPHR robustly applied this information to national guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force and six other guidelines to provide a very personalised overview of recommended preventive services.33–40 All recommendations include personalised explanations of the information in plain language, tailored motivational messages, links to additional educational resources and decision aids, tools to promote action and periodic reminders. The information is shared with both the patient through the IPHR portal and their clinician via their EHR.

While multiple studies have evaluated why patients use PHRs with more basic functionality,10 16 less is known about their interests in and engagement with PHRs with more advanced patient-centred functionality as provided by the IPHR. As part of our ongoing trials, we used qualitative methods to capture perspectives from both ‘users’ and patients who were invited to use the IPHR but did not use the system (‘non-users’), with a lens towards informing the knowledge gaps and varying viewpoints about PHR adoption noted above. As framed by Kuzel,41, this inquiry was “driven not by a need to generalise or predict, but rather by a need to create and test… interpretations.”

Methods

Design

We employed descriptive and interpretive analysis of focus group transcripts and field notes, with data reduction via coding and editing for development of major themes and subthemes. We then used a combination of grounded theory and editing analysis42 with initial codes derived from key emergent themes from our interpretive analysis. A trained moderator led the focus groups, using broad-based questions to explore patients’ perspectives about the IPHR and PHRs in general. A focus group guide was used to ensure consistency of procedures, questions and discussion topics. The guide, developed from ‘discussions with experts familiar with the topic’,42 and focus group process were based on the methods described by Crabtree and Miller42 and by McNamara.43 At the beginning of each patient focus group, participants completed a brief printed questionnaire eliciting demographic characteristics and information about interactions with their clinician. The study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board.

Sample

All participants were patients from one of eight family medicine practices that were located in northern Virginia and participated in the Virginia Ambulatory Care Outcomes Research Network (ACORN). In order to address sampling adequacy, a minimum total of 12 participants in both user and non-user groups was targeted.44 During the first 4 months the IPHR was available to the practices, 229 of the 2250 patients randomly selected and mailed an invitation used the tool (completed registration and entered data on the website). All of these patients were invited through email to participate in focus groups. Of the 44 who expressed interest, 30 selected to provide a range of ages, genders and practice locations were asked to participate in three user focus groups. (The first user group was rescheduled due to inclement weather and 3 of 10 participants ultimately attended. The next two groups had 5 and 6 of 10 invited participants attend, respectively.) Of the 2021 non-users, a random sample of 150 patients, stratified by age, gender and practice location, were mailed focus group invitations. From the 32 patients who responded to the letter, 20 selected to provide a range of ages, genders and practice locations were asked to participate in two non-user focus groups; 14 attended. Each participant received a $50 gift card incentive.

Procedures

Focus groups, each approximately 1.5–2 h in duration, were held at a location near the participating practices. Group discussion was guided by semistructured questions with probes and prompts to provide follow-up lines of inquiry, clarify topics and stimulate further discussion. The user and the non-user groups were shown screen-shots demonstrating how the IPHR worked at appropriate times during the groups so all participants could comment on the IPHR attributes and uses. Sessions were audio-recorded, and the transcriptions of the recordings were then corrected as necessary through comparison with the original recordings. Field notes were also taken to capture aspects of the group interaction that would not be identified on recordings. This included such observations as participant body language and tone, as well as researcher thoughts and reactions.

Transcripts and field notes underwent descriptive analysis with a provisional categorical structure based on focus group question guides. Data were combined with field notes to explore descriptive similarities and differences within and between the groups. Coding and editing of transcripts and field notes were used to derive higher level themes and explanations, and tentative explanations of findings were based on both our data and relevant literature. A four-member team (JWK, AHK, DRL and AJK) performed each step of the analysis independently. Differences in coding, development of themes and derivation of tentative explanations were discussed by the team until consensus was reached. Model development ensued (AHK and JWK), building on key emergent themes from the interpretive analysis. Initially concentrated on contextual thematic interrelationships (eg, linked Venn diagrams), resultant thematic modifications resulted in iterations of models which were ‘based on both process and causal considerations’.26

Results

Study population

The patients who used the IPHR during the study period were primarily men (56%), white (85%) and more than 50 years old (68%). Of the 50 patients who agreed to participate in focus groups (30 users and 20 non-users), 28 patients attended the sessions, including 14 PHR users and 14 non-users (table 1). Focus group participants were predominantly women (64%), white (93%), over 50 years old (86%) and all reported having attended at least some college. Nearly allii participants rated their health as good to excellent, stated they had been with their clinician at least 3 years, and rated their clinician highly.

Table 1.

Focus group participants

| Participant characteristics | 3 PHR user groups (n=14) | 2 PHR non-user groups (n=14) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 5 male 9 female |

5 male 9 female |

ns |

| Mean age (years) | 66 (range 50–77) | 59 (range 40–75) | 0.07 |

| White (%) | 100 | 86 | ns |

| Participant-reported education, Number of participants |

Some college/associate degree-5 College graduate-2 More than college degree-7 |

Some college/associate degree-2 College Graduate-3 More than college degree-9 |

ns |

| Participant-reported number of years with current clinician | 2 participants <1 year 4 participants 3–5 years 8 participants >5 years |

0 participants <1 year 8 participants 3–5 years 6 participants >5 years |

ns |

| Mean participant-reported visits per year | 3.6 | 3.4 | ns |

| Mean participant quality rating of current clinician | 9.23/10 0=worst doctor possible 10=best doctor possible |

9.00/10 0=worst doctor possible 10=best doctor possible |

ns |

| Patient-reported health rating, number of participants | Excellent 4 Very good 6 Good 3 Fair 0 Poor 1 |

Excellent 3 Very good 7 Good 3 Fair 1 Poor 0 |

ns |

ns, not significant; PHR, personal health records.

All but one focus group participant acknowledged using the internet daily, and some described ‘constant’ internet use for job and personal purposes. Although nearly all stated that they did not use the internet as often for health-related matters as for other needs, they did report using the internet to garner health information, primarily for themselves and their family.

Themes

Across all five focus groups,iii three major themes emerged about how participants wanted to be engaged by PHRs: they wanted (1) novel content that was relevant to their immediate and ongoing care, (2) a PHR they could trust for accuracy, security and privacy and (3) a highly functional PHR, facilitating care and communication with their clinician, and providing access to comprehensive personalised information shared with the clinician. Although practical usefulness was said to be essential, a major reason why participants said they trusted, used and sought relevance in the IPHR was that it was offered to them by their personal clinician.

Relevance

A few participants noted that upcoming appointments with their clinician made the IPHR use more compelling, contributed to their registering, and led them to notice the content pertinent to that visit. Most, however, reported that the invitation for the IPHR was received at a time unassociated with an office visit or any specific healthcare needs. Indeed many participants reported that as a result they did not feel a pressing need to immediately register for and use the IPHR (table 2). A few non-users declared that they just had not gotten around to registering. Many participants in the non-user and the user groups voiced the opinion that they could access similar information on the internet, and that they did not recognise that the IPHR content was personalised to their needs. Some users commented that they had already fully addressed their preventive healthcare needs with their clinician.

Table 2.

Representative participant comments on relevance of the interactive prevention health record (IPHR) (Why they didn't feel a need to register)

| Subthemes | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Lacking urgency |

It was procrastination. It wasn't that I wasn't going to do it. I said, “Boy, this would be—this is interesting, I should try it.” Stuck it in a pile and forgot about it. |

| Lacking novelty |

Particularly when it concerns a medical something, I usually look it up, you know, any of the various websites that you can go to. I am the health related expert in the house. And I have to know what everything is. So yes I go to the Cleveland Clinic and the Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins. |

| Redundant to Current care |

It was not, in my case not new information since my doctor and I had talked about it so much… She knows what I do for exercise, and she asks me questions when I go in, you know. But, if I didn't have that kind of relationship, then I think I would—I mean, right now, I don't see, for me, that I need this. |

Trust

Nearly all participants vigorously discussed three components of trust necessary for them to use a PHR: security (protecting their health information), privacy (not sharing their health information with others) and accuracy (ensuring that the clinical content and health recommendations proffered by the system were correct and appropriate for them; table 3). Most participants reported trusting the IPHR because it was recommended and used by their clinician's practice. A few participants in the non-user groups indicated discomfort with having any of their personal health information on the internet. However, most participants in all groups expressed the view that clinician endorsement of the IPHR was an indication that their personal health data were secure. Most participants also expressed strong opposition to PHRs developed by commercial entities and to sharing their health information with their insurance company due to the risk of future denial of coverage.

Table 3.

Representative participant comments on trust of an interactive prevention health record (IPHR)

| Subthemes | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Security |

It (IPHR) came through our own doctor; I didn't have any problem with it. If it had just been out of the blue I might have. At first I was curious as to what is this (IPHR), but then I guess I trusted it because it was [clinician's office] which I trusted. I've come to trust him to keep my information in his laptop…you have to trust the doctor. |

| Privacy |

I think personally I would only trust what I was affiliated with. What should be familiar with me. I mean, Google certainly doesn't know me… Another Participant: Oh, Yes they do. The information you have on the system, passing data maybe to insurance companies and then turn around later and say no we're not going to insure you… I got scared…because I got the impression that I was going to discuss things of my personal nature with my doctor on the website and I didn't like that, and so I discarded it because I'd rather talk about my health face to face with my doctor. |

| Accuracy |

There's so many sites out there that you wonder how valid. I felt good that [the clinician's office was] endorsing or leading me to a particular site that they must feel confident in the information and the content. One reason I don't do (Internet health information) a whole lot is because you get conflicting views and I don't know who to believe and who not to believe. So I…ask my doctor. I was getting emotionally distraught over those things that I was reading (on the Internet) and then, come to find out, I didn't even have to be concerned about it. But… I got to leave those kinds of things to the doctor because that's what he's trained for. |

Nearly all participants reported having had difficulties distinguishing between accurate and inaccurate health information on the internet (table 3). A few participants gave examples of erroneous health information that caused anxiety or led to poor personal health choices. Most participants stated that they asked their clinician to verify information they found on the web. Nearly all participants reported that they would trust the accuracy of the content and recommendations made by the IPHR because it was endorsed and used by their clinician, and identified their clinician as their primary authority on the accuracy and application of healthcare information.

Functionality

Functions that the participants identified as important involved two subthemes: enhanced patient–clinician communication and patient-centred utility (table 4).

Table 4.

Representative participant comments on functionality enhanced patient–clinician communication from using an interactive prevention health record (IPHR)

| Subthemes | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Interactive |

Direct communications between the doctor and the patient that you can access via the Internet just like medical records, you should be able to access that. (As a result of using the IPHR) The nurse called me up and said we haven't seen you in so long, you know, and she starts going through this (prevention) stuff…I said well I've been going to my heart doctor…and she said, you should come back you know. Not dictating, but cooperating, supportive, and provide me the source of the information, let me go there and look at the thing (IPHR) before, you know we make a decision. |

| Focus discussion |

I have 15 minutes to talk to him. And this gives me the ability to list everything that's wrong with me...This is what you need to talk to the doctor about in your physical. I would think anything that would focus my discussion would hopefully focus his as well. When I go in to the primary care physician, I don't want to just listen to him. I do want to hear what he has to say, but I want to be able to ask what I think are intelligent questions. I'll go do research on that. And then I feel like I can have a better, more productive discussion with the physician. |

| Broaden discussion |

What if your doctor disagrees somewhat with the United States Preventive Services Task Force? (as recommended by the IPHR)...It becomes a discussion point. I think it (conversation with clinician) might be a little bit broader (from using the IPHR). You go and say, “Here's what I'm seeing or here's what going on with my family.” |

| Efficiency Pros and Cons |

There might be an opportunity to take some of the minor issues off the table(after using the PHR), so when you go to the doctor it would shorten the amount of things that you would like to talk to him about because you've answered some of that already. That email to the doctor, I think, could create a problem. It's very time consuming. You spend all day on the internet answering mail, the doctor will never get paid…SECOND PARTICIPANT: You'd never get your tetanus shot. FIRST PARTICIPANT: ..You'd never get anything else. So what is this doing for the physician? I mean, we're keeping healthier, but it means a lot more work for him in a way. |

| Patient-centred IPHR utility | |

| Expand access to personal clinical information | It's not just security, but also access. My access to my personal information. I want to have that, and electronic medical records, Internet-based systems can provide me with that. I trust my physician here because I've developed a relationship with him, but anybody else, I would want to have absolute access to my information. |

| Align patient-clinician information |

Knowing that all the information is correct to the best of your knowledge, and in one place where it can be accessed by the doctor and by you, it makes me feel very secure. This information is shared with your physician –– as you update things your provider is going to be made aware of this you know-We need to be on the same page. |

| Provide personalised information |

I think with that information available (in the IPHR), I think it will actually help him a great deal to change my lifestyle. I think that's what all this preventive medicine is all about is how you change your lifestyle. It also gave me some thoughts about the preventive things I should need to know or that I should be thinking about. So it made me think about, gosh I'll have to ask her. For example, something about an aspirin a day, is it something that's appropriate for me? There was lots of information there but it was not, in my case not new information since my doctor and I had talked about it so much... |

| Comprehensively address patient needs |

I'm surprised that this isn't something for medications. One doctor says you got to take calcium and another one says you got to take multivitamin and another one says you got to take an aspirin, and people may be taking allergy medicines that they get over the counter… Some general thing about menopause or some of the women's issues would have been helpful. Age specific things might be helpful, children, you know, developmental or something like that just as a good reference for parents. Say you had in your history that you had a history of stroke or cancer, would it also give patient education stuff, like here's a link to the American Cancer Society? Or here's a thing for support group information? I'm a surviving cancer patient… Here's what we want: we're living here but we want to occasionally go somewhere else. Anyone in the country should be able to open and keep track of it accurately…realistically and securely. |

Many participants stated that they wanted PHRs to enhance communication with their clinician both electronically and in person. Several liked being contacted about preventive care after they used the IPHR. Participants described how the IPHR could focus discussions during office visits, making their visits more productive. Conversely, several also mentioned that the IPHR could appropriately broaden discussions for some topics, such as identifying preventive screening choices that they or their clinician viewed as warranting dialogue, or starting conversations about lifestyle changes. However, some participants expressed concern that more time would be required for busy clinicians and patients to use the IPHR or similar tools. Participants worried about increased fees for either patients or practices to use similar PHRs in the future.

Many participants said that a critically important feature of the IPHR was the ability for patients to access their personal health information. They explained that this access was important so that they could be ‘on the same page’ as their clinician. They also commented that shared access to information would contribute to improved accuracy of records and more productive interactions.

Many participants identified the personalised advice offered by the IPHR, its prompts to discuss its recommendations with the clinician (eg, whether to take aspirin), and its ability to prioritise recommendations and thereby highlight critical or information to act on, as very important. Also of interest to many (but not available in this IPHR) were adding features for comprehensive medication reconciliation, in-depth information for the whole family for prevention as well as for specific diseases, and links to local resources that provide support and information for lifestyle changes, preventive care needs and chronic diseases. Moreover, several participants stated that PHRs, such as the IPHR, should be shared seamlessly across all healthcare providers and settings.

Discussion

Given the national investment of $27 billion to promote the adoption, implementation and meaningful use of health information technology,9 45 46 it is essential to understand how to better engage patients in using technology if it is to achieve its full potential. Many Americans have not embraced the use of PHRs,47 but our findings underscore the general interest of patients in using such tools if certain attributes are offered.

When PHR use is integrated into care so that it improves the efficiency and quality of patients’ care (eg, timely use related to clinician visits), its relevance becomes more transparent. The PHR becomes a welcome extension of interactions with the clinician and the related healthcare team.

National surveys have clearly documented a level of public concern about personal health information existing on the web and about employers, insurers or even commercial entities being able to access or misuse such information.47 Although one could argue that such fears may ease over time as more private information migrates into the cyber-environment, this reticence may have already contributed to the failure of some commercial PHRs to gain wide acceptance by the general public.48

The addition of certain PHR features that seem popular with patients, such as displaying test results or supporting asynchronous communication via secure messaging, has generated only modest increases in actual PHR utilisation.17 21 One explanation is that patients who are accustomed to more powerful information tools in other aspects of life may expect greater functionality than merely seeing their information.49 50 Indeed, participants in this study wanted much more—including links to personalised recommendations, and resources and tools to help make information actionable to improve health, as provided by this IPHR.

Across the users and the non-users, nearly all participants reported being more likely to perceive a PHR as relevant, trustworthy and functional if it was offered to them by their personal clinician. We conclude that a key element of engaging patients to use a PHR extends beyond the tool's design and includes how it is presented to patients and integrated into their care experience (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Personal health record features needed to engage patients.

Although some PHR evaluations seem to show enhanced patient uptake when patients had a lack of trust in their clinician,51 52 other information seems to indicate that encouragement of PHR uptake by a patient's clinician has a positive influence on patient use and that patient and clinician PHR use enhances their relationship.53 Our findings support Nazi's findings53 and extend them to show, as in figure 1, that the patient–clinician relationship explicitly supports all critical components of patient engagement in the IPHRs.

Other models, among them DeLone and McLean's26 MISS (figure 2), have been applied to clinical information systems, including PHRs. Booth states that MISS lacks sensitivities to medical and relationship-laden milieus of technology (previously described by Sandelowski),29 54 whereas figure 1 and our results demonstrate clinical as well as personal contexts for patients and clinicians. Further, although Archer et al23 used MISS to categorise aspects of their scoping review of PHRs, they only examined selected parts of the model.

Figure 2.

Delone and Mclean's model of information system success.26 From William H. Delone and Ephraim R. McLean, “The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update,” Journal of Management Information Systems 19(4) (Spring 2003), 24. Copyright © 2003 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All Rights Reserved. Not for Reproduction.

Differences between figure 1 and MISS aside, we wish to point out several similarities as well, including the previously mentioned use of causal and process elements, and the feedback loop from ‘Net Benefits’ to ‘Use’ and ‘User Satisfaction’.

Our study has several important limitations. First, while we attempted to assemble focus groups with a representative range of ages and genders, we may have introduced a selection bias in our sample. Participants were older, more likely to be female, mostly white, and more educated than the overall user and non-user populations.55 56 However, women are more likely than men to use PHRs57 and to make healthcare decisions for families.57–59 Other studies indicate that members of different socioeconomic and racial-ethnic groups may have different PHR preferences (eg, a PHR not based on the internet) and may require assistance in using a PHR.60–62 Second, the sample was drawn entirely from eight practices in northern Virginia. Other locales may have different PHR needs requiring different strategies to engage patients in PHR use. Third, all participants were recruited from family medicine offices that already offered PHR to patients, and most participants had established relationships with their clinician. Accordingly, participants may have emphasised the value of the patient–clinician relationship in PHR use more than populations from other settings. Finally, whereas the number of participants (28) will not quantitatively generalise to all IPHR users, the nature of qualitative research is often that of looking at specific cases, many times in order to inform the gaps generated by other data, rather than to compete with or duplicate that information.42

Conclusion

To engage primary care patients with an IPHR, this study identifies the importance of relevance, trust and functionality, all integrated with office processes and the patient–clinician relationship. In addition to suggesting possible modifications to established models of technological acceptance, these findings have relevance for healthcare providers, the information technology industry and policymakers who share an interest in encouraging patients to use PHRs or other information tools. Studies like ours should be expanded and replicated in other settings to more fully understand how to make such technology more useful to patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating study practices: Fairfax Family Practice, Gainesville Family Medicine, Herndon Family Medicine, Lorton Station Family Medicine, Prince William Family Medicine, South Riding Family Medicine, Town Center Family Medicine, and Vienna Family Medicine. We received invaluable advice and assistance with the focus groups from Christine C Kerns, RN, and in designing the project from Stephen F Rothemich MD, MS as well as Kristin Schmidt in project assistance.

(Herein ‘clinician’ means physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant.)

The following is used for the verbal annotation of participant percentages: All=100%, nearly all=80–99%, most=60–80%, many=40–60%, a majority= >50%, some=25–40%, few=<25%.

Unless otherwise indicated, findings described herein are from both the user and the non-user groups.

Contributors: JWK was involved in design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, drafting/critical revision and final approval. AHK was involved in conceptualisation, design, data analysis/interpretation, critical revision and final approval. DRL was involved in design, data analysis, critical revision and final approval. AJK design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, critical revision and final approval. SHW was involved in conceptualisation, data analysis/interpretation, critical revision and final approval.

Funding: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R18 HS17046-01).

Competing interests: Virginia Commonwealth University holds the intellectual property rights to the interactive preventive care record evaluated in this study. Although the university and developers are entitled to the system's revenue, MyPreventiveCare is a non-commercial product, and no revenues have been generated other than grant funding.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Transcripts for the focus groups in this study are not able to be shared due to requirements of our Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, et al. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ 2001;322:444–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med 1985;102:520–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 1989;27:S110–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatricians, American Osteopathic Association. http://www.pcpcc.net/ (accessed Oct 2011).

- 6.NCQA—Measuring Quality Improving Health Care. National Committee for Quality Assurance. http://www.ncqa.org (accessed Oct 2011).

- 7.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Section 4103. Public Law 111–148. 2nd Session ed; 2010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bielaszka-DuVernay C, Soll RF, Kantak AD, et al. Vermont's blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost evaluating the medical evidence for quality improvement management of high-order multiple births: application of lessons learned because of participation in Vermont Oxford Network collaboratives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;30:383–621383346 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The meaningful use regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med 2010;363:501–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health IT The office of the national coordinator for health information technology. US Department of Health & Human Services; http://healthit.hhs.gov (accessed July 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hing E, Burt CW. Office-based medical practices: methods and estimates from the national ambulatory medical care survey. Adv Data 2007(383):1–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krist AH, Woolf SH. A vision for patient-centered health information systems. JAMA 2011;305:300–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CJ, Huang JT. Integrating technology into healthcare: what will it take? JAMA 2012;307:569–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen H. A (very) popular health record. http://xnet.kp.org/newscenter/pressreleases/nat/2012/080612_4_million_phr_registered_users.html (accessed May 2013).

- 15.Poorsina R, Wardell A. Four million people choose connectivity and convenience with Kaiser Permanente's personal health record. http://www.va.gov/health/NewsFeatures/2013/March/A-Very-Popular-Personal-Health-Record.asp (accessed May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Internet usage over time Pew Internet and American Life. http://www.pewinternet.org/ (accessed Oct 2011).

- 17.Silvestre AL, Sue VM, Allen JY. If you build it, will they come? The Kaiser Permanente model of online health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:334–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ralston JD, Coleman K, Reid RJ, et al. Patient experience should be part of meaningful-use criteria. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:607–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang PC, Lee TH. Your doctor's office or the Internet? Two paths to personal health records. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1276–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CAHPS Clinician & Group Survey Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/content/products/CG/PROD_CG_CG40Products.asp?p=1021&s=213 (accessed Sep 2011).

- 21.Dickinson WP, Glasgow RE, Fisher L, et al. Use of a website to accomplish health behavior change: if you build it, will they come? and will it work if they do? J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26:168–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen KY, Kreps G, Zhu F, et al. Consumers’ perceptions about and use of the internet for personal health records and health information exchange: analysis of the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Archer N, Fevrier-Thomas U, Lokker C, et al. Personal health records: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:515e522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsythe DE. New bottles, old wine. Hidden cultural assumptions in a computerized explanation system for migraine sufferers. Med Anthro Quart 1996;10:551–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKnight DH, Carter M, Thatcher JB, et al. Trust in a specific technology: an investigation of its components and measures. ACM Trans Manag Info Syst 2011;2:1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeLone WH, McLean ER. The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: a ten-year update. J Manag Info Syst 2003;19:9–30 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 1989;13:319–39 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moores TT. Towards an integrated model of IT acceptance in healthcare. Decis Support Syst 2012;53:507–16 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Booth RG. Examining the functionality of the DeLone and McLean information system success model as a framework for synthesis in nursing information and communication technology research. Comput Inform Nurs 2012;30:330–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Designing a patient-centered personal health record to promote preventive care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2011;11:73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krist AH, Woolf SH, Rothemich SF, et al. Interactive preventive health record to enhance delivery of recommended care: a randomized trial. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:312–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Family Medicine Virginia Commonwealth University. A How-To Guide for Using Patient-Centered Personal Health Records to Promote Prevention. 2012. http://healthit.ahrq.gov/KRIST-IPHR-Guide-0612.pdf (accessed Jun 2012).

- 33.Complete Report: the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee of Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Vol NIH Pub. No. 04-5239. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation 2004;110:227–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Cholesterol Education Program Third report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. Vol NIH Pub. No. 02-5215 Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of medical care in diabetes. II. Testing for pre-diabetes and diabetes in asymptomatic patients. Diabetes Care 2008;31(Suppl 1):S13–14 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Recommendation and Guidelines: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/ACIP/default.htm (accessed Jan 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd edn Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dietary Guidelines for Americans Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Agriculture 2005. http://www.healthierus.gov/dietaryguidelines/ (accessed Jul 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd edn Sage Oaks, 1999:34 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd edn Sage Oaks, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNamara C. Basics of Conducting Focus Groups. http://managementhelp.org/businessresearch/focus-groups.htm (accessed Oct 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing qualitative Research. 2 edn Sage Oaks, 1999:42 [Google Scholar]

- 45.The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c111:H.R.1 (accessed Jun 2012).

- 46.Ackerman K. Heavy hitters hit HIMSS stages to stump for health IT iHealthBeat. http://www.ihealthbeat.org/features/2011/heavy-hitters-hit-himss-stages-to-stump-for-health-it.aspx (accessed Jun 2012).

- 47.Connecting for Health Americans overwhelmingly believe electronic personal health records could improve their health. Markle Foundation, 2008. http://www.connectingforhealth.org/resources/ResearchBrief-200806.pdf (accessed Jun 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 48.An Update on Google Health, Google, Official Blog, 2011. http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/update-on-google-health-and-google.html#!/2011/06/update-on-google-health-and-google.html (accessed Jun 2012).

- 49.Wakefield DS, Kruse RL, Wakefield BJ, et al. Consistency of patient preferences about a secure internet-based patient communications portal: contemplating, enrolling and using. Am J Med Qual 2012;27:494–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weitzman ER, Kaci L, Mandl KD. Acceptability of a personally controlled health record in a community-based setting: implications for policy and design. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisher B, Bhavnani V, Winfield M. How patients use access to their full health records: a qualitative study of patients in general practice. J R Soc Med 2009;102:539–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wibe T, Hellesø R, Slaughter L, et al. Lay people's experiences with reading their medical record. Social Sci Med 2011;72:1570–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nazi KM. The personal health record paradox: health care professionals’ perspectives and the information ecology of personal health record systems in organizational and clinical settings. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandelowski M. (Ir)Reconcilable differences? The debate concerning nursing and technology. J Nurs Scholarsh 1997;29:169–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krist AH, McCormally T. What patients want from their doctor's website. Fam Med 2001;33:552 [Google Scholar]

- 56.State and County Quick Facts, United states Census Bureau. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/51/51059.html (accessed Feb 2012).

- 57.Rice RE. Influences, usage, and outcomes of Internet health information searching: multivariate results from the Pew surveys. Int J Med Inform 2006;75:8–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller EA, West DM. Characteristics associated with use of public and private web sites as sources of health care information results from a national survey. Med Care 2007;45:245–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ybarraa ML, Sumanb M. Help seeking behavior and the Internet: a national survey. Int J MedInform 2006;75:29–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamin CK, Emani S, Williams DH, et al. The digital divide in adoption and use of a personal health record. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:568–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bagchi A, Moreno L, Af Ursin R. Considerations in designing personal health records for underserved populations. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2007. http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/pdfs/hlthcaredisparib1.pdf (accessed Feb 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moreno L, Peterson S, Bagchi A, et al. Personal health records: what do underserved consumers want? Mathematica Policy Research, Inc, 2007. http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/PDFs/phrissuebr.pdf (accessed Feb 2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.