Abstract

Objectives

The study aimed to determine if having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP) is a risk factor for future cardiovascular disease (CVD), independent of age and body mass index (BMI).

Design

Data were sourced from the baseline questionnaire of the 45 and Up Study, Australia, an observational cohort study.

Setting

Participants were randomly selected from the Australian Medicare Database within New South Wales.

Participants

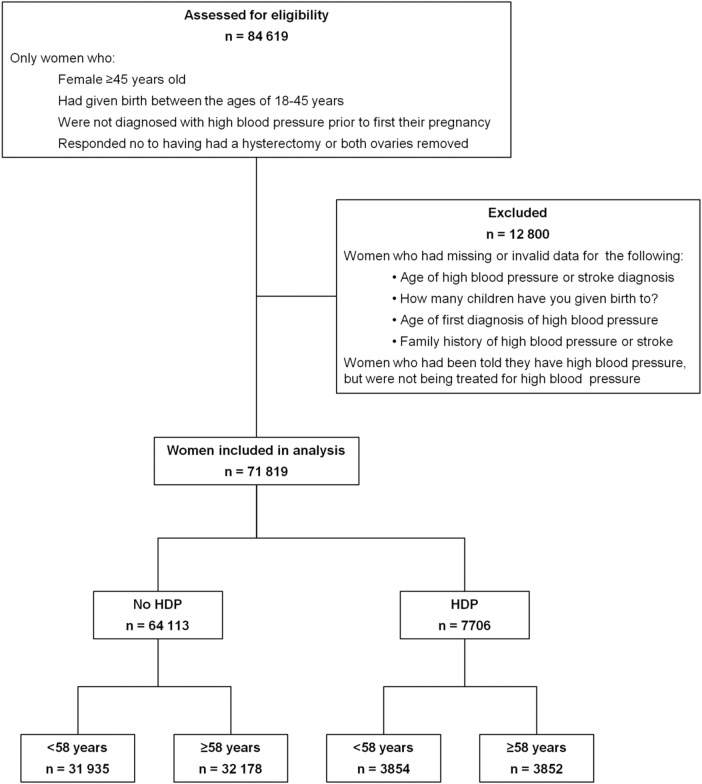

A total of 84 619 women were eligible for this study, of which 71 819 were included. These women had given birth between the ages of 18 and 45 years, had an intact uterus and ovaries, and had not been diagnosed with high blood pressure prior to their first pregnancy.

Results

HDP was associated with higher odds of having high blood pressure (<58 years: adjusted OR 3.79, 99% CI 3.38 to 4.24; p<0.001 and ≥58 years: 2.83, 2.58 to 3.12; p<0.001) and stroke (<58 years: 1.69, 1.02 to 2.82; p=0.008 and ≥58 years: 1.46, 1.13 to 1.88; p<0.001) in later life. Women with HDP had a younger age of onset of high blood pressure (45.6 vs 54.8 years, p<0.001) and stroke (58 vs 62.5 years, p<0.001). Women who had HDP and whose present day BMI was <25 had significantly higher odds of having high blood pressure, compared with women who were normotensive during pregnancy (<58 years: 4.55, 3.63 to 5.71; p<0.001 and ≥58 years, 2.94, 2.49 to 3.47; p<0.001). Women who had HDP and a present day BMI≥25 had significantly increased odds of high blood pressure (<58 years: 12.48, 10.63 to 14.66; p<0.001 and ≥58 years, 5.16, 4.54 to 5.86; p<0.001), compared with healthy weight women with a normotensive pregnancy.

Conclusions

HDP is an independent risk factor for future CVD, and this risk is further exacerbated by the presence of overweight or obesity in later life.

Article summary.

Article focus

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) have been associated with an increased risk of maternal cardiovascular disease (CVD) in later life.

It remains unclear whether high blood pressure during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for future CVD or whether it is confounded by traditional risk factors such as age and body mass index.

Key messages

Our study shows that a history of HDP is significantly associated with having high blood pressure and stroke in later life.

HDP is an independent risk factor for future CVD and the risk of CVD is further exacerbated by the presence of overweight or obesity in later life, particularly in women <58 years of age.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a large observational cohort study which included 71 819 women.

These data are unable to differentiate between the different categories of HDP and the timing of onset of the disease during pregnancy.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major contributor to worldwide morbidity and mortality and is the leading cause of death in the USA in individuals aged 65 years and over.1 In Australia, approximately two million women are affected by CVD and the three leading causes of death in women are coronary heart disease, stroke and other heart diseases (including heart failure).2 Age is a powerful predictor of CVD, with increasing age associated with increasing arterial stiffness3 and endothelial dysfunction,4 which predisposes the individual to high blood pressure and premature ageing of the vascular system.5 Excess body fat is also a known risk factor for arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction and subsequent CVD.6 7

Recent evidence has demonstrated that women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) have increased arterial stiffness,8 and these women may be at a greater risk of future CVD when compared with women who experience a normotensive pregnancy.9 HDP, which include gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, chronic hypertension and superimposed pre-eclampsia on chronic hypertension, occur in 5–10% of all pregnancies within Australia.10 Women with HDP experience an abnormal response to the placenta with shallow vascular invasion of the placental trophoblasts, which leads to an ischaemic placenta.11 This causes the placenta to release antiangiogenic proteins, which result in endothelial dysfunction. The clinical features of the maternal response to this abnormality include hypertension, renal impairment, liver impairment, pulmonary oedema, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy and neurological disturbances. It can exacerbate existing endothelial dysfunction in women with chronic high blood pressure. The endothelial damage caused by HDP was thought to disappear immediately following birth as the mother's blood pressure returned to its normal value, and the endothelium appeared to return to its pre-pregnancy state.12 Studies have now shown that endothelial damage can persist beyond a pregnancy diagnosed with HDP. It is this damage that is thought to increase the risk of developing CVD in later life when compared to women who remain normotensive during pregnancy.13–15

The aim of this study was to determine whether women who reported having had an HDP were at an increased likelihood of having high blood pressure or stroke in later life, using observational data from the 45 and Up Study, Australia. We also aimed to determine how this association was modified by a woman's age and body mass index (BMI) and whether the age of onset of high blood pressure or stroke in later life differed between women who had HDP and those who remained normotensive.

Methods

Study sample

This study obtained data from women participating in the 45 and Up Study, a large-scale cohort study of 267 153 men and women aged 45 years and over in New South Wales, Australia. Participants were randomly selected from the Australian Medicare Database which provides near-complete coverage of the population. The participants were enrolled into the study by consenting to and completing a baseline questionnaire (available at http://www.45andUp.org.au) and giving consent for long-term follow-up through data linkage and repeat data collection. People aged 80 years and over, and residents of rural and remote areas were oversampled. Study recruitment started in January 2006 and was completed in April 2009. The methods for the 45 and Up Study have been described elsewhere.16 Exposure–outcome relationships estimated from the 45 and Up Study data have been shown to be consistent with another large study of the same population, regardless of the underlying response rate or mode of questionnaire administration.17

All the data used in this study were acquired from the 45 and Up Study baseline questionnaire. Women were included in this study if: they were age 45 years or more, had given birth between 18 and 45 years of age, had not had a hysterectomy or both ovaries removed and were not diagnosed with high blood pressure prior to their first pregnancy (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participants included in the study.

Women were identified as having had HDP if they responded with “Yes” to the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you have: high blood pressure—when pregnant.” Where the age of ‘high blood pressure—when pregnant’ was within 1 year of the woman's age when she first gave birth, HDP was identified as occurring during her first pregnancy. Where the age of ‘high blood pressure—when pregnant’ was greater than 1 year from the woman's age when she first gave birth, HDP was identified as occurring during a subsequent pregnancy.

Women were identified as having high blood pressure when not pregnant if they answered “Yes” to the question “In the last month have you been treated for: high blood pressure.” Women were identified as having a stroke if they answered “Yes” to the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you have: stroke.” Women were excluded if: they reported having high blood pressure prior to having their first child; answered “Yes” to “Has a doctor ever told you that you have: high blood pressure—when not pregnant” but were not being treated for high blood pressure; they failed to provide an age of onset for high blood pressure or stroke; they provided invalid data for family history or they provided invalid data for the number of children they had given birth to in their specified age range (figure 1). Classification of demographic and lifestyle characteristics have been described elsewhere.18

Statistics

ORs and 99% CIs for the association between (1) demographic and lifestyle characteristics and HDP, (2) HDP and high blood pressure in later life and (3) HDP and stroke in later life were estimated using logistic regression. Analyses were repeated for (2) and (3) combining HDP status (yes or no) and BMI (<25 or ≥25) into a single variable with four categories. Crude and adjusted ORs were calculated and descriptions referred to adjusted ORs unless otherwise specified. Owing to the known association between high blood pressure and ageing, women were stratified according to age using the median age as the cut-off point (<58 years, ≥58 years) when testing the association between HDP and high blood pressure as well as stroke in later life. ORs were adjusted for country of origin, income level, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, family history of high blood pressure (for high blood pressure analysis), family history of stroke (for stroke analysis), history of oral contraceptive use, history of menopausal hormone therapy and number of children. Categories for each covariate have been described previously.18 An additional category for missing values was included for variables with missing data. Linear regression was used to study the association between age of onset of high blood pressure and stroke and HDP. All statistical tests were two sided, using a significance level of p<0.01 to partially account for multiple testing issues.19 All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software V.20 (IBM Corp, New York, USA).

Results

A total of 84 619 women were eligible for the study (figure 1). These women had given birth between the ages 18–45 years, had an intact uterus and had not been diagnosed with high blood pressure prior to their first pregnancy. Of these women, 71 819 were included in the study (exclusion criteria shown in figure 1), of which 7706 (10.7%) reported having had HDP. Of these, 3237 (42%) reported current treatment for high blood pressure and 165 (2.1%) reported having had a stroke. In comparison, of the 64 113 women who did not report HDP, 10 668(16.6%) reported current treatment for high blood pressure and 913 (1.4%) reported having had a stroke. There was no significant difference in odds for having high blood pressure (OR 1.02, 99% CI 0.88 to 1.16; p=0.77) or stroke (OR 0.99, 99% CI 0.64 to 1.54; p=0.97) between HDP during first pregnancy compared with HDP in a subsequent pregnancy. As a result, the analysis grouped all women who reported HDP, irrespective of which pregnancy it had occurred in.

The association between sociodemographic factors and whether a woman had HDP is shown in table 1. A positive family history of high blood pressure and stroke, oral contraceptive use, and having three or more children were associated with significantly higher odds of having had HDP. Women who were current smokers had reduced odds of having had HDP compared with women who had never smoked.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic factors and health risk factors associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP)

| Characteristics | Status | N (%, column) | Percentage of HDP | OR (99% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of high blood pressure | No | 33 349 (46) | 7 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 38 470 (54) | 14 | 2.14 (2.00 to 2.30)* | |

| Family history of stroke | No | 53 416 (74) | 10 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 18 403 (26) | 13 | 1.13 (1.05 to 1.21)* | |

| Smoking status | Never | 46 832 (65) | 11 | 1.00 |

| Past | 19 996 (28) | 11 | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | |

| Current | 4669 (7) | 9 | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.91)* | |

| Past oral contraceptive use | No | 12 339 (17) | 9 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 58 440 (81) | 11 | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.40)* | |

| Number of children | 1 | 7581 (11) | 9 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 29 298 (41) | 10 | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.23) | |

| 3 | 21 441 (30) | 11 | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.38)* | |

| 4 or more | 13 499 (19) | 12 | 1.46 (1.29 to 1.65)* |

Percentage of HDP is the percentage of women who responded with ‘yes’ to having had high blood pressure during pregnancy. Percentages do not consistently total to 100% due to missing values.

*p<0.01.

†Adjusted for family history of high blood pressure and stroke, smoking status, history of oral contraceptive use and number of children.

HDP was associated with increased odds of having high blood pressure in later life (women <58 years: OR 3.79, 99% CI 3.38 to 4.24; p<0.001) compared with women who remained normotensive during their pregnancy (table 2). The average age of onset of high blood pressure in later life was 45.6 years for women who had HDP compared with 54.8 years for women who remained normotensive during their pregnancy (adjusted β=−8.30, 99% CI −8.89 to −7.71; p<0.001).

Table 2.

Association between high blood pressure when pregnant and maternal CVD in later life

| CVD | Current age | HDP | Cases (n) | Crude OR (99% CI) | Adjusted OR (99% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure | <58 | No | 31 935 | 1.00 reference | |

| Yes | 3 854 | 4.89 (4.40 to 5.43) | 3.79 (3.38 to 4.24)* | ||

| ≥58 | No | 32 178 | 1.00 reference | ||

| Yes | 3852 | 3.51 (3.21 to 3.84) | 2.83 (2.58 to 3.12)* | ||

| Stroke | <58 | No | 35 613 | 1.00 reference | |

| Yes | 176 | 1.92 (1.17 to 3.16) | 1.69 (1.02 to 2.82)* | ||

| ≥58 | No | 35 128 | 1.00 reference | ||

| Yes | 902 | 1.45 (1.13 to 1.85) | 1.46 (1.13 to 1.88)* |

*p<0.01.

†Analysis adjusted for country of origin, income level, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, family history of high blood pressure (for high blood pressure analysis) and stroke (for stroke analysis), history of oral contraceptive use and menopausal hormone therapy and number of children.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Stratification of women according to HDP status and BMI found that women who had HDP and whose current BMI was ≥25 had significantly increased odds of having high blood pressure (women <58 years: OR 12.48, 99% CI 10.63 to 14.66; p<0.001 and women ≥58 years: OR 5.15, 99% CI 4.54 to 5.86; p<0.001) compared with women who did not have HDP and whose present day BMI was <25 (figure 2). Women who had HDP and whose present day BMI was <25 had significantly higher odds of having high blood pressure, compared with women who did not have HDP and whose present day BMI was ≥25 (women <58 years: OR 1.33, 99% CI 1.08 to 1.64; p<0.001 and women ≥58 years: OR 1.56, 99% CI 1.33 to 1.83; p<0.001).

Figure 2.

The odds of having high blood pressure depending on a woman's body mass index (BMI) and whether she had a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP), compared with women with present-day BMI<25 who were normotensive during pregnancy, stratified by current age.

HDP was also associated with increased odds of having stroke in later life (women <58 years: OR 1.69, 99% CI 1.02 to 2.82; p<0.001 and women ≥58 years: OR 1.46, 99% CI 1.13 to 1.88; p<0.001) compared with women who remained normotensive during their pregnancy (table 2). The average age of onset of stroke in later life was 58 years for women who had HDP compared with 62.5 years for women who remained normotensive during their pregnancy (adjusted β= –4.01, 99% CI −6.87 to −1.16; p<0.001).

Stratification of women according to HDP status and BMI found that women who had HDP and whose current BMI was ≥25 had significantly increased odds of having stroke (women <58 years: OR 2.24, 99% CI 1.14 to 4.42; p=0.002 and women ≥58 years: OR 1.46, 99% CI 1.05 to 2.04; p=0.003) compared with women who did not have HDP and whose present day BMI was <25 (figure 3). There was no significant difference in odds of having stroke in the other groups of women (BMI≥25 and no HDP, and BMI<25 and yes HDP), compared with women of healthy weight who had remained normotensive during their pregnancy.

Figure 3.

The odds of having a stroke depending on a woman's body mass index (BMI) and whether she had a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP), compared with women with present-day BMI <25 who were normotensive during pregnancy, stratified by current age.

Discussion

The 45 and Up Study is the largest self-reported cohort of Australian women ever examined. Our results show that having an HDP is associated with significantly increased odds of having high blood pressure in later life, compared with women that remained normotensive, and this was exacerbated in women with BMI≥25 kg/m2. Women who reported having HDP were 9.2 years younger at the age of onset of high blood pressure, compared with women who experienced healthy pregnancies. Similarly, women who suffered from HDP had significantly higher odds of having stroke compared with women who remained normotensive during their pregnancy and the age of onset of stroke was significantly earlier in women with HDP. Women within the healthy weight range in our study, who had experienced HDP, had significantly higher odds of having present-day high blood pressure compared with similar aged women who were overweight or obese, but who had been normotensive during pregnancy. Women who had both risk factors, namely BMI≥25 kg/m2 and HDP, had up to 12.48 increased odds of having high blood pressure and up to 2.24 increased odds of stroke, compared with women within the healthy weight range with normotensive pregnancies. This shows that HDP is an independent risk factor for future high blood pressure and when combined with traditional risk factors, such as BMI, a history of HDP can significantly increase the odds of future CVD.

This study analysed cross-sectional and observational data from the baseline questionnaire from the 45 and Up Study. As a result, the causal nature of associations could not be assessed. Our data may have a selection bias with regard to the prevalence of stroke, as only women who survived their stroke were able to be surveyed. These data are unable to differentiate between the different categories of HDP, severity of the disease, duration of the pregnancy, timing of onset of the disease during pregnancy and the relationship between the timing of high blood pressure and the timing of delivery. Other studies have shown that the more severe the high blood pressure and the earlier its onset during pregnancy, the greater was the risk of future high blood pressure compared with women who suffered a milder or more moderate form of the disease.20 21 In our study, the prevalence of high blood pressure in pregnancy was 10.7%, which is higher than what has been reported previously in the literature at 8.7%.10 This may be explained by self-reported data recall bias or the systematic under-reporting of HDP.22

Our results support existing evidence of a link between HDP and subsequent cardiovascular risk. Studies have shown that women who had HDP have a greater risk of cardiovascular morbidity, including an increased risk of hypertension, stroke and coronary heart disease,14 23 and that CVD is more common in these women within one to two decades of having hypertension during pregnancy.24–27 Our study extends these findings by showing that women with HDP have a significantly younger age of onset of high blood pressure and stroke. HDP was significantly associated with increased odds of future CVD in all age groups analysed, but the odds reduced with increasing age, demonstrating age as an independent predictor of future CVD.

HDP shares many of the aetiologies of CVD, such as inflammation and endothelial changes, as well as having overlapping risk factors, such as obesity, insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia. Sustained endothelial dysfunction caused by damage to the endothelium during HDP may be responsible for the long-term consequences observed in these women. Alternatively, pre-existing endothelial dysfunction prior to conception may be a triggering mechanism for HDP as well as increasing the risk for CVD later in life.15 Studies have shown that endothelial dysfunction persists in women following HDP, namely pre-eclampsia.13 15 28 29 Additionally, studies have found a strong link between pre-eclampsia and higher circulating concentrations of fasting insulin,30 lipid and coagulation factors31 post partum. High BMI is also known to adversely influence the endothelium,7 and endothelial dysfunction is an early risk factor for future catastrophic CVD events in obese adults.32 An inherited predisposition to endothelial dysfunction, obesity or insulin resistance may explain the increased odds of CVD in women who had HDP, where the development of HDP was an early warning sign unmasking the genetic predisposition due to the stress of pregnancy.33 This increased risk of CVD is further exacerbated by the presence of overweight or obesity in later life, particularly in women <58 years of age.

HDP are associated with higher odds of having CVD in later life and also constitute an independent risk factor for future CVD. Women who are overweight or obese and have HDP have significantly higher odds of having high blood pressure and stroke in later life. This study adds to the evidence34 that a woman's pregnancy history is important when assessing her future risk of CVD. Women who experience HDP should be closely monitored for cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure, hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia in the years following pregnancy. Women should be encouraged to maintain a healthy weight, particularly if they experience HDP. Future research within this field should focus on the association between the severity of HDP and future CVD, whether different treatment strategies for HDP result in varied CVD health outcomes, and whether monitoring and early intervention (such as lifestyle modification) following pregnancy can help minimise the risk of future CVD in women who experienced HDP.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JML supervised the study and was responsible for the statistical analysis. She had full access to all the data in the study, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and is the guarantor. JT, CLC, KY, SJL, CT, AM, AOL, AH and JML conceived and designed the study. JT, CLC, KY and JML drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in interpreting the data and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with the major partner Cancer Council New South Wales; and partners the National Heart Foundation of Australia (New South Wales Division); New South Wales Ministry of Health; beyondblue: the national depression initiative; Ageing, Disability and Home Care, New South Wales Family and Community Services; Australian Red Cross Blood Service and UnitingCare Ageing.

Competing interests: JML is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council—Australian Biomedical Fellowship. JT is supported by a PEARLS (Preeclampsia Research Laboratories) PhD scholarship. SJL is the recipient of a University of Western Sydney Postgraduate Research Award and an Ingham Health Research Institute scholarship. KY is the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award and a University of Western Sydney scholarship.

Ethics approval: The 45 and Up Study received ethics approval from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 10186) and the current study was approved by the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (H8561).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control Ten leading causes of death and injury. Atlanta, 2009. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/LeadingCauses.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Women and heart disease: cardiovascular profile of women in Australia. Cat. no. CVD. Canberra: AIHW, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell GF, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, et al. Changes in arterial stiffness and wave reflection with advancing age in healthy men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2004;43:1239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seals DR, Jablonski KL, Donato AJ. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;120:357–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wildman RP, Mackey RH, Bostom A, et al. Measures of obesity are associated with vascular stiffness in young and older adults. Hypertension 2003;42:468–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton-Tyrrell K, Newman A, Simonsick EM, et al. Aortic stiffness is associated with visceral adiposity in older adults enrolled in the study of health, aging, and body composition. Hypertension 2001;38:429–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blann AD, Bushell D, Davies A, et al. von Willebrand factor, the endothelium and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1993;17:723–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaihura C, Savvidou MD, Anderson JM, et al. Maternal arterial stiffness in pregnancies affected by preeclampsia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;297:H759–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ 2001;323:1213–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts CL, Bell JC, Ford JB, et al. The accuracy of reporting of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in population health data. Hypertens Pregnancy 2008;27:285–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science 2005;308:1592–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, et al. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:1200–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agatisa PK, Ness RB, Roberts JM, et al. Impairment of endothelial function in women with a history of preeclampsia: an indicator of cardiovascular risk. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286:H1389–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007;335:974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Germain AM, Romanik MC, Guerra I, et al. Endothelial dysfunction: a link among preeclampsia, recurrent pregnancy loss, and future cardiovascular events? Hypertension 2007;49:90–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks E, Redman S, Jorm L, et al. Cohort profile: the 45 and up study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:941–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mealing NM, Banks E, Jorm LR, et al. Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu CL, Lujic S, Thornton C, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy is associated with having high blood pressure in postmenopausal women: observational cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e40260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1990;1:43–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, et al. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J 2008;156:918–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wikstrom AK, Haglund B, Olovsson M, et al. The risk of maternal ischaemic heart disease after gestational hypertensive disease. BJOG 2005;112:1486–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thornton C, Hennessy A, Grobman WA. Benchmarking and patient safety in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2011;25:509–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis EF, Newton L, Lewandowski AJ, et al. Pre-eclampsia and offspring cardiovascular health: mechanistic insights from experimental studies. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;123:53–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin R, Gorostidi M, Portal CG, et al. Long-term prognosis of hypertension in pregnancy. Hypertens Pregnancy 2000;19:199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nisell H, Lintu H, Lunell NO, et al. Blood pressure and renal function seven years after pregnancy complicated by hypertension. BJOG 1995;102:876–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnadottir GA, Geirsson RT, Arngrimsson R, et al. Cardiovascular death in women who had hypertension in pregnancy: a case-control study. BJOG 2005;112:286–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdes G, Quezada F, Marchant E, et al. Association of remote hypertension in pregnancy with coronary artery disease: a case-control study. Hypertension 2009;53:733–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, et al. Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA 2001;285:1607–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramsay JE, Stewart F, Greer IA, et al. Microvascular dysfunction: a link between pre-eclampsia and maternal coronary heart disease. BJOG 2003;110:1029–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laivuori H, Tikkanen MJ, Ylikorkala O. Hyperinsulinemia 17 years after preeclamptic first pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:2908–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He S, Silveira A, Hamsten A, et al. Haemostatic, endothelial and lipoprotein parameters and blood pressure levels in women with a history of preeclampsia. Thromb Haemost 1999;81:538–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta AK, Ravussin E, Johannsen DL, et al. Endothelial dysfunction: an early cardiovascular risk marker in asymptomatic obese individuals with prediabetes. Br J Med Med Res 2012;2:413–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg G, Khankin EV, Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic factors and preeclampsia. Thromb Res 2009;123(Suppl 2):S93–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spaan J, Peeters L, Spaanderman M, et al. Cardiovascular risk management after a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Hypertension 2012;60:1368–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.