Abstract

Objectives

To compare the mortality in those previously hospitalised for mental disorder in Scotland to that experienced by the general population.

Design

Population-based historical cohort study using routinely available psychiatric hospital discharge and death records.

Setting

All Scotland.

Participants

Individuals with a first hospital admission for mental disorder between 1986 and 2009 who had died by 31 December 2010 (34 243 individuals).

Outcomes

The main outcome measure was death from any cause, 1986–2010. Excess mortality was presented as standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) and years of life lost (YLL). Excess mortality was assessed overall and by age, sex, main psychiatric diagnosis, whether the psychiatric diagnosis was ‘complicated’ (ie, additional mental or physical ill-health diagnoses present), cause of death and time period of first admission.

Results

111 504 people were included in the study, and 34 243 had died by 31 December 2010. The average reduction in life expectancy for the whole cohort was 17 years, with eating disorders (39-year reduction) and ‘complicated’ personality disorders (27.5-year reduction) being worst affected. ‘Natural’ causes of death such as cardiovascular disease showed modestly elevated relative risk (SMR1.7), but accounted for 67% of all deaths and 54% of the total burden of YLL. Non-natural deaths such as suicide showed higher relative risk (SMR5.2) and tended to occur at a younger age, but were less common overall (11% of all deaths and 22% of all YLL). Having a ‘complicated’ diagnosis tended to elevate the risk of early death. No worsening of the overall excess mortality experienced by individuals with previous psychiatric admission over time was observed.

Conclusions

Early death for those hospitalised with mental disorder is common, and represents a significant inequality even in well-developed healthcare systems. Prevention of suicide and cardiovascular disease deserves particular attention in the mentally disordered.

Keywords: Mental Health, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

Examines whether those previously hospitalised for mental disorder die earlier than people with no overt serious mental disorder.

Do individuals with ‘complicated’ diagnoses (ie, additional mental or physical ill-health diagnoses in conjunction with their main psychiatric diagnosis) have higher excess mortality than those with ‘uncomplicated’ diagnoses?

Is the apparent inequality in mortality rates between those with serious mental disorder and the general population worsening over time?

Key messages

The average reduction in lifespan in those previously hospitalised for mental disorder compared with the general population is 17 years. People with eating disorders and personality disorder died earliest of all.

In general, patients with ‘complicated’ diagnoses experience higher excess mortality than those without.

Cardiovascular and respiratory diseases were the most common causes of death and accounted for a high proportion of the total burden of years of life lost (YLL), but suicides led to more YLL at the individual level due to predominantly affecting younger adults. No worsening of the ‘mortality gap’ over three decades was observed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A large representative population studied over a long time period, which is important when examining causes of death.

Innovative use of a diagnostic hierarchy to determine individuals’ main psychiatric diagnosis.

People with mental disorder who never required inpatient hospital care could not be included in this study.

Many of the most disabling medical conditions worldwide are mental illnesses, according to the WHO.1 As well as adversely affecting day-to-day function, it has been known for many years that people with mental illness are at increased risk of premature death2–4 with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in particular being associated with an early death.5–7 These inequalities in life expectancy have recently8 been declared a ‘scandal’, as even the Scandinavian countries,4 Scotland9 and England,7 10 despite relatively high quality and equitably distributed healthcare, have not been able to demonstrate any improvement in this premature mortality for the mentally ill over many years.

Non-natural deaths,11 including suicide and accidents, account for a disproportionate amount of this premature mortality in the mentally ill, particularly affecting young adults. High rates of cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and other so-called natural causes also contribute4 12 13 to the elevated relative risk of early death in the mentally ill. Precise estimates of the varying causal contributions to premature mortality in the mentally disordered have been limited by the lack of large representative populations being followed up over a lengthy period, and related studies have usually focused on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder7 14 rather than all major mental disorders. Additionally, the effects of comorbidity or multiple diagnoses on this premature mortality have also not been quantified. Concern has also been expressed that those with mental illness have not benefitted from improvements in public health over the last few decades8 13 and that this mortality gap between the general population and the mentally ill is widening in recent years.

Using routinely collected national data, available from 1981, we set out to examine the ages and causes of death in those previously hospitalised with mental disorder in Scotland, and quantify any excess mortality. We also aimed to explore the relative contribution of different causes of death and trends over time.

Methods

Whenever a patient is discharged from a mental ill-health hospital/specialty in Scotland, a Scottish Morbidity Record for Mental ill health (SMR04) is returned to the NHS National Services Scotland Information Services Division (ISD). SMR04 records contain information on patient demographics such as personal identifiers, age and sex; the diagnosis that necessitated the admission; and the aspects of the care given such as the psychiatric subspecialty admitted to. One primary diagnosis and up to five further secondary diagnoses can be recorded. Diagnoses are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (V.9 to 1997 and V.10 from 1997 to present). Statutory death records (containing demographic and ICD coded cause of death information) are returned to the National Records of Scotland with copies passed to ISD for analytical purposes.

For this study, SMR04 records for adults discharged from mental ill-health hospitals/specialities in Scotland between 1981 and 2009 were obtained. Patients aged less than 15 years at the date of first admission and those admitted to the learning disabilities subspecialty were excluded from the sample, in accordance with the aim of studying the ages and causes of death in adults with mental illness and personality disorder. Death records for the period 1986–2010 were also obtained. We created a single patient record for each individual by linking all their hospital discharge records and their death record (if died) using a range of patient identifiers and previously developed probabilistic matching algorithms. These methods have been described previously.15 16 All patients who had had an admission to a mental ill-health specialty between 1981 and 1985 were excluded to give a cohort of patients with (as close as possible to) a first inpatient admission between 1986 and 2009 in order to clarify the issue of diagnostic shift or comorbidity.

All patient level data used in this study were held and analysed within ISD. Only aggregate results, from which individual patients could not be identified, were shared with members of the study team not based within ISD (MT). ISD operates strict procedures to maintain patient privacy and confidentiality and no specific additional permissions were required for this study. In particular, permission for the linkage of previously unlinked health datasets held by ISD is required from the Privacy Advisory Committee. PAC approval was not required for this study, as SMR04 and death records have been routinely linked within ISD for decades for purposes such as monitoring patient outcomes.

Diagnostic assignation

We then assigned each individual to a main psychiatric diagnosis category (see table 1) and excluded individuals who did not have any admissions relating to a diagnostic group of interest. The diagnostic groups of interest included were schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, neurosis, eating disorder and personality disorder.

Table 1.

Main psychiatric diagnosis categories of interest (and diagnostic hierarchy)

| Main psychiatric diagnosis category | Definition | Hierarchy |

|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders including acute psychosis, persistent delusional disorders, schizotypal and schizoaffective disorder, and drug or alcohol-induced psychotic disorder | 1 |

| Bipolar disorder | Manic episodes and bipolar disorder | 2 |

| Depression | Depressive episodes and recurrent depressive disorder (excluding persistent mood disorders such as cyclothymia) | 3 |

| Neurosis | Anxiety disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder | 4 |

| Eating disorder | Anorexia and bulimia nervosa | 5 |

| Personality disorder | All types of personality disorder | 6 |

Note: International Classification of diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes are available on request.

Patients with a single primary psychiatric diagnosis of interest recorded on all their psychiatric discharge records over the period of study, and no other or additional diagnoses at any admission were described as ‘uncomplicated’. For example, an individual with five hospital admissions which were all coded solely to depression would be described as ‘uncomplicated depression’.

In contrast, patients with more than one diagnosis recorded were described as ‘complicated’. For patients with more than one diagnosis from the diagnostic groups of interest, a hierarchical approach was used to determine the main diagnosis and hence assign a patient to one group (see table 1) with schizophrenia being assigned the highest rank. For example, a patient diagnosed as having bipolar disorder at their first hospital admission and then admitted for neurosis at a later date would be assigned to the ‘complicated bipolar’ group. Conversely, someone who had three hospital admissions for neurosis and then one for neurosis with depression recorded as an additional secondary diagnosis would be described as ‘complicated depression’ and their time at risk in the cohort would be taken from their first neurosis admission.

Patients may also have had other/additional diagnoses not within the diagnostic groups of interest. These included other psychiatric problems (mainly dementia, stress reactions and adjustment disorders); alcohol or drug misuse; or (rarely) physical health problems such as pneumonia. Someone with an admission for personality disorder with drug misuse recorded as an additional secondary diagnosis would therefore be described as ‘complicated personality disorder’.

Analysis

A final record was then created for each patient within the mental ill-health cohort containing hierarchically defined main psychiatric diagnosis, a flag indicating whether the main diagnosis was ‘complicated’ or not, date of first admission, age at first admission, sex, deprivation category at first admission, date of death and (main) cause of death. Deprivation category was determined using Carstairs 1991 area-based deprivation deciles17 based on postcode of residence at first admission and corresponding population denominators from the Consistent Areas Through Time (CATTS) classification tables18 which allows us to create a long time series of deprivation-specific mortality rates.

This linked dataset was used to calculate indirectly standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) for the mental ill-health patients using a person-years approach which took account of each individual's time at risk (from time of first admission) across different age categories, time periods, sex and deprivation decile since diagnosis. All analyses were carried out using Stata V.11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA) using the stsplit command to split age (in days) across the time periods. Age was defined in days from birth date to diagnosis date, and study exit was defined in days from diagnosis date to end of follow-up interval or death, whichever came first.

Years of life lost (YLL) were computed by multiplying the number of deaths in the study cohort (in each period of death, sex, age band at death and deprivation decile) by the corresponding life expectancy at that age. The average YLL (AYLL) was derived by dividing the total YLL by the actual number of deaths within the subgroups of interest. Scottish national mortality rates split by year of death (in time bands), sex, 5-year age band and deprivation decile were used as the reference standard for the SMRs. Life tables were compiled based on these national mortality rates following the Chiang19 methodology for the YLL analyses. To examine the possible trends over time in the excess mortality experienced by individuals with previous psychiatric admission, we chose three time period cohorts each with 10 years of follow-up for each cohort to capture a wide range of causes of death.

We looked at overall mortality; mortality by specific cause; and mortality split into natural deaths (cardiovascular, cancer, respiratory, digestive, endocrine, nervous system, infectious disease), non-natural deaths (accidental, suicide/undetermined, homicide) and other (all other deaths including those recorded as mental and behavioural).

Results

Over the time period of study (1986–2009), there were 59 028 individuals who had a consistent diagnosis within and between admissions (classified as uncomplicated) and 52 476 individuals who had an unstable diagnosis or additional comorbidity within and/or between admissions (classified as complicated). Women comprised 55% of the cohort largely due to a higher number of cases of depression in women. Women tended to be older than men at their first included admission, particularly for schizophrenia and neurosis. Complicated diagnoses resulted in higher numbers of hospitalisations and total length of time spent in hospital as would be expected (see table 2A,B).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the cohort included in the analysis

| N | Per cent | Median age at first admission (IQR) | Percentage in most deprived quintile* | Median number of admissions (IQR) | Median total length (days) on admission (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Male | ||||||

| Uncomplicated diagnosis group | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 8966 | 35 | 33.7 (24.6–50.2) | 29 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 48.0 (16.0–161.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1680 | 7 | 41.0 (28.4–56.2) | 17 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 36.0 (17.0–72.0) |

| Depression | 12 778 | 49 | 47.5 (34.2–66.0) | 23 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 22.0 (7.0–53.0) |

| Neurosis | 1129 | 4 | 40.7 (29.8–58.5) | 26 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 14.0 (5.0–35.0) |

| Eating disorder | 49 | <1 | 22.1 (19.0–28.8) | 33 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 48.0 (12.0–89.0) |

| Personality disorder | 1221 | 5 | 30.9 (23.8–41.7) | 30 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 8.0 (3.0–24.0) |

| Total uncomplicated | 25 823 | 100 | 40.9 (28.4–59.6) | 25 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 28.0 (9.0–74.0) |

| Complicated (hierarchical) diagnosis group | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 10 697 | 43 | 31.0 (23.3–44.0) | 33 | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 145.0 (52.0–429.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | 2159 | 9 | 42.4 (30.5–56.6) | 21 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 115.0 (51.0–257.0) |

| Depression | 9421 | 38 | 40.1 (30.0–54.9) | 26 | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 44.0 (18.0–105.0) |

| Neurosis | 915 | 4 | 37.0 (27.4–48.1) | 24 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 32.0 (14.0–71.0) |

| Eating disorder | 17 | <1 | 31.3 (23.5–48.5) | 29 | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 45.0 (21.0–148.0) |

| Personality disorder | 1580 | 6 | 31.3 (23.8–41.6) | 31 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 21.0 (8.0–49.0) |

| Total complicated | 24 789 | 100 | 35.5 (26.0–49.9) | 28 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 73.0 (26.0–214.0) |

| B. Female | ||||||

| Uncomplicated diagnosis group | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 6999 | 21 | 53.9 (34.5–76.0) | 25 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 47.0 (19.0–122.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | 2196 | 7 | 43.4 (30.5–61.0) | 18 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 35.0 (17.0–74.0) |

| Depression | 20 383 | 61 | 48.5 (33.8–69.1) | 23 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 28.0 (10.0–65.0) |

| Neurosis | 1946 | 6 | 48.5 (33.7–68.7) | 26 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 18.0 (7.0–39.0) |

| Eating disorder | 586 | 2 | 20.7 (17.5–26.5) | 16 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 49.0 (13.0–126.0) |

| Personality disorder | 1095 | 3 | 31.1 (23.0–43.5) | 27 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 9.0 (3.0–25.0) |

| Total uncomplicated | 33 205 | 100 | 47.6 (32.5–69.5) | 23 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 30.0 (11.0–73.0) |

| Complicated (hierarchical) diagnosis group† | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 8230 | 30 | 40.6 (27.7–66.0) | 29 | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 162.0 (68.0–410.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | 3619 | 13 | 43.0 (31.2–59.8) | 22 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 136.0 (60.0–313.0) |

| Depression | 13 390 | 48 | 41.1 (29.8–61.8) | 25 | 2.0 (2.0–4.0) | 64.0 (25.0–163.0) |

| Neurosis | 1136 | 4 | 42.9 (31.2–63.6) | 21 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 38.0 (17.0–91.5) |

| Eating disorder | 199 | 1 | 26.2 (20.7–34.3) | 18 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 35.0 (10.0–103.0) |

| Personality disorder | 1113 | 4 | 29.5 (22.5–40.3) | 28 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 27.0 (10.0–60.0) |

| Total complicated | 27 687 | 100 | 40.6 (28.8–61.9) | 26 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 89.0 (33.0–237.0) |

*If there had been no deprivation gradient then around 20% of cases would be in the most deprived quintile.

†For individuals with a complicated mental health diagnosis (hierarchical), the age at first admission refers to the first ‘ever’ admission event.

Increasing deprivation was linked to mental ill-health problems for both men and women, with the exception of bi-polar disorder (no clear trend across deprivation groups for either sex) and eating disorder in women (uncomplicated more common in least deprived group; complicated no clear trend across deprivation groups; table 2 and additional analyses available on request).

Overall, 34 243 individuals in the study cohort had died by the 31 December 2010, around 80% more (SMR=1.8) than expected based on the general population (see table 3). The SMRs tended to be higher for those with complicated diagnoses, and overall were highest for those with eating disorders (SMR=4.4) and complicated personality disorders (SMR=3.1). Overall life expectancy for the whole cohort of individuals with mental ill health was 17 years less than that for the general population. The largest reduction in life expectancy was seen for individuals with eating disorders (39 YLL for those with uncomplicated diagnosis) and personality disorders (27.5 YLL for those with complicated diagnosis), however, as most deaths were seen in individuals with depression and schizophrenia, these conditions accounted for the greatest number of YLL.

Table 3.

SMRs and years of life lost for all-cause mortality by diagnosis group (all patients diagnosed 1986–2009 and followed up until 31 December 2010)

| Observed deaths | Expected deaths | SMR* (95% CI) | Total YLL | Average YLL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated diagnosis group | |||||

| Schizophrenia | 5060 | 2746 | 1.84 (1.79 to 1.89) | 78 027 | 15.2 |

| Bi-polar | 883 | 525.6 | 1.68 (1.57 to 1.79) | 14 369 | 16.1 |

| Depression | 11 036 | 6831.2 | 1.62 (1.59 to 1.65) | 155 582 | 14.1 |

| Neurotic disorders | 838 | 524.7 | 1.60 (1.49 to 1.71) | 12 373 | 14.9 |

| Eating disorders | 51 | 11.6 | 4.39 (3.27 to 5.77) | 2182 | 39.0 |

| Personality disorders | 449 | 234.9 | 1.91 (1.74 to 2.10) | 10 583 | 22.8 |

| Complicated (hierarchical) diagnosis group | |||||

| Schizophrenia | 5635 | 2876.9 | 1.96 (1.91 to 2.01) | 116 775 | 19.6 |

| Bi-polar | 1706 | 1129.5 | 1.51 (1.44 to 1.58) | 29 351 | 16.7 |

| Depression | 7282 | 3628.8 | 2.01 (1.96 to 2.05) | 146 736 | 19.0 |

| Neurotic disorders | 579 | 272.8 | 2.12 (1.95 to 2.30) | 12 194 | 19.9 |

| Eating disorders | 38 | 8.7 | 4.39 (3.10 to 6.03) | 1317 | 31.4 |

| Personality disorders | 686 | 221.9 | 3.09 (2.86 to 3.33) | 20 894 | 27.5 |

| Total | 34 243 | 19 012.4 | 1.80 (1.78 to 1.82) | 600 383 | 17.0 |

*Adjusted for sex, age, period and deprivation category (Carstairs 1991 decile) at first diagnosis.

SMR, standardised mortality ratio; YLL, years of life lost.

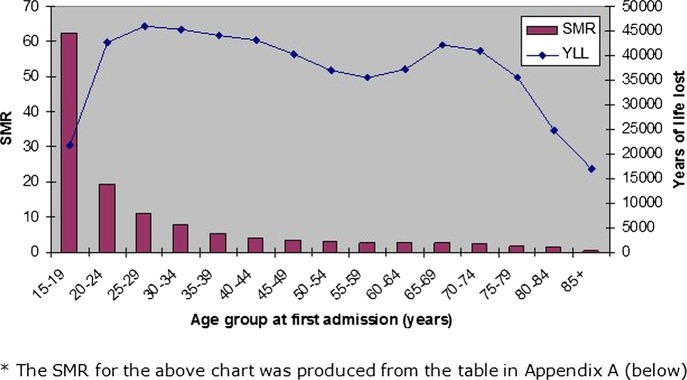

Relative risk of early death

The excess risk of death was extremely high for those in the youngest age group at first included admission, and the excess reduced as age at first admission increased (see figure 1). However, total YLL told a slightly different story, with a relatively constant YLL for those diagnosed at ages 20–24 through to 75–79 years, with lower YLL for those aged 15–19, 80–84 and 85+ years. This reflects the fact that the absolute risk of dying generally increases with age. The same age-related pattern is seen for men and women, although the excess risk of death is higher for women compared with men at every age (data not shown).

Figure 1.

All-cause standardised mortality ratios and overall years of life lost for patients diagnosed 1986–2009 and followed up until 31 December 2010 by age group at first admission.

Around two-thirds of deaths (22 865 deaths) in the mental ill-health cohort were from natural causes, 11% (3909) from non-natural causes and the remaining 21% (7469) were from ‘other’ deaths not coded as natural or non-natural including ‘mental or behavioural disorder’ (36% of ‘other’ causes of death). The excess risk of death was much higher from non-natural causes (SMR=5.2) compared with natural causes (SMR=1.7) and ‘other’ deaths (SMR=1.6). On average, 31.8 years of life were lost due to every non-natural death compared with 13.3 years due to every natural death and 17.4 YLL for each ‘other’ death, reflecting the fact that non-natural deaths tend to occur at younger ages (see table 4).

Table 4.

SMRs and years of life lost by diagnosis group and cause of death grouping (natural death, non-natural death or ‘other’ deaths; all patients diagnosed 1986–2009 and followed up until 31 December 2010)

| Natural deaths |

Non-natural deaths |

Other deaths |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | SMR (95% CI) | AYYL | N | SMR (95% CI) | AYYL | N | SMR (95% CI) | AYYL | |

| Uncomplicated diagnosis group | |||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 3580 | 1.78 (1.72 to 1.84) | 11.8 | 504 | 4.40 (4.02 to 4.80) | 32.2 | 976 | 1.58 (1.48 to 1.68) | 16.3 |

| Bi-polar | 624 | 1.69 (1.56 to 1.83) | 13.0 | 97 | 4.74 (3.84 to 5.78) | 32.0 | 162 | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.38) | 16.4 |

| Depression | 7839 | 1.60 (1.56 to 1.63) | 12.0 | 1055 | 4.93 (4.64 to 5.24) | 27.2 | 2142 | 1.25 (1.20 to 1.30) | 13.8 |

| Neurotic disorders | 622 | 1.71 (1.58 to 1.85) | 13.2 | 63 | 3.35 (2.57 to 4.29) | 29.4 | 153 | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.26) | 15.1 |

| Eating disorders | 15 | 2.57 (1.44 to 4.26) | 23.8 | 12 | 7.21 (3.71 to 12.63) | 49.5 | 24 | 5.81 (3.72 to 8.66) | 39.3 |

| Personality disorders | 265 | 1.67 (1.48 to 1.88) | 15.0 | 96 | 6.21 (5.03 to 7.58) | 37.6 | 88 | 1.45 (1.16 to 1.79) | 25.6 |

| Complicated (hierarchical) diagnosis group | |||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 3500 | 1.71 (1.65 to 1.77) | 14.3 | 767 | 5.17 (4.81 to 5.55) | 35.1 | 1368 | 2.02 (1.91 to 2.13) | 20.0 |

| Bi-polar | 1,139 | 1.43 (1.34 to 1.51) | 13.7 | 197 | 5.06 (4.38 to 5.82) | 30.8 | 370 | 1.27 (1.14 to 1.41) | 15.7 |

| Depression | 4525 | 1.78 (1.72 to 1.83) | 14.8 | 931 | 6.54 (6.12 to 6.97) | 32.3 | 1,826 | 1.94 (1.86 to 2.04) | 18.6 |

| Neurotic disorders | 379 | 2.04 (1.84 to 2.25) | 16.4 | 53 | 4.28 (3.20 to 5.60) | 33.6 | 147 | 1.98 (1.67 to 2.33) | 20.0 |

| Eating disorders | 17 | 3.00 (1.74 to 4.82) | 24.4 | 5 | 8.99 (2.84 to 21.14) | 43.1 | 16 | 6.56 (3.74 to 10.68) | 32.9 |

| Personality disorders | 360 | 2.46 (2.21 to 2.73) | 19.9 | 129 | 7.47 (6.24 to 8.88) | 39.0 | 197 | 3.37 (2.92 to 3.88) | 28.8 |

| Total | 22865 | 1.69 (1.67 to 1.71) | 13.3 | 3909 | 5.25 (5.08 to 5.41) | 31.80 | 7,469 | 1.58 (1.55 to 1.62) | 17.4 |

*Adjusted for sex, age, period and deprivation category (Carstairs 1991 decile) at first diagnosis.

AYLL, average years of life lost; SMR, standardised mortality ratio.

There was a significant excess risk of natural, non-natural and ‘other’ deaths for patients in each diagnosis group (except uncomplicated neurotic disorders resulting in ‘other’ deaths (SMR=1.1, ns)). The highest excess risks were seen for eating disorders across death groupings, although the number of deaths in individuals with eating disorders was small (table 4). Natural deaths accounted for more YLL than non-natural deaths in each diagnostic group. Cardiovascular disease accounted for around half of all YLL from natural causes, with digestive disorders, cancer and respiratory disorders accounting for most of the remainder. Suicide accounted for the majority of YLL due to non-natural causes in each diagnostic group (data not shown). Table 5 reveals the proportions of observed deaths for the two main natural causes of death, namely heart disease and cancer, as well as suicide, the main causes of unnatural death.

Table 5.

Standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) for cardiovascular disease; cancer; and suicide

| Cardiovascular deaths* |

Cancer deaths† |

Suicide deaths† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of natural deaths | SMR (95% CI) | Percentage of natural deaths | SMR (95% CI) | Percentage of unnatural deaths | SMR (95% CI) | |

| Uncomplicated diagnosis group | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 53 | 1.72 (1.65 to 1.80) | 12 | 1.30 (1.18 to 1.43) | 63 | 8.05 (7.19 to 8.98) |

| Bi-polar | 54 | 1.69 (1.51 to 1.88) | 15 | 1.39 (1.12 to 1.69) | 74 | 9.70 (7.59 to 12.22) |

| Depression | 55 | 1.59 (1.54 to 1.64) | 15 | 1.35 (1.28 to 1.43) | 75 | 13.28 (12.37 to 14.24) |

| Neurotic disorders | 50 | 1.60 (1.43 to 1.79) | 14 | 1.37 (1.10 to 1.69) | 65 | 6.44 (4.62 to 8.75) |

| Eating disorders | 40 | 2.30 (0.83 to 5.04) | 20 | 2.92 (0.55 to 8.65) | 92 | 12.22 (6.07 to 21.94) |

| Personality disorders | 51 | 1.62 (1.36 to 1.91) | 12 | 1.17 (0.80 to 1.66) | 65 | 8.58 (6.57 to 11.00) |

| Complicated diagnosis group | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 50 | 1.57 (1.50 to 1.65) | 9 | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) | 72 | 9.05 (8.31 to 9.83) |

| Bi-polar | 52 | 1.40 (1.29 to 1.52) | 12 | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.05) | 77 | 11.57 (9.80 to 13.57) |

| Depression | 49 | 1.62 (1.56 to 1.69) | 10 | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.11) | 74 | 13.25 (12.28 to 14.27) |

| Neurotic disorders | 44 | 1.65 (1.41 to 1.92) | 12 | 1.34 (0.98 to 1.81) | 70 | 7.52 (5.29 to 10.37) |

| Eating disorders | 29 | 1.68 (0.53 to 3.95) | 12 | 2.06 (0.19 to 7.56) | 100 | 19.49 (6.15 to 45.85) |

| Personality disorders | 43 | 2.08 (1.76 to 2.43) | 10 | 1.32 (0.92 to 1.82) | 71 | 10.55 (8.49 to 12.95) |

All cardiovascular deaths.

*All cancer, including lung cancer, deaths.

†All deaths coded as suicides.

‡Cardiovascular and cancer deaths are shown as a proportion of observed natural deaths within each category and suicide is shown as a proportion of observed unnatural deaths within each category.

Mortality trends over time

Looking at individuals whose first admissions were in the periods 1986–1990, 1991–1995 and 1996–2000 and following each individual in these subcohorts up for 10 years from their first admission, the all cause SMRs showed no evidence of a narrowing of the mortality excess over time (table 6).

Table 6.

Standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) by time period of first admission (1986–2000) and followed up for 10 years from first admission (all diagnosis groups combined)

| Period of first admission | Observed deaths | Expected deaths | SMR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | |||

| 1986–1990 | 3185 | 1514 | 2.10 (2.03 to 2.18) |

| 1991–1995 | 2878 | 1328 | 2.17 (2.09 to 2.25) |

| 1996–2000 | 2327 | 1076 | 2.16 (2.08 to 2.25) |

| Females | |||

| 1986–1990 | 4808 | 2669 | 1.80 (1.75 to 1.85) |

| 1991–1995 | 3882 | 2112 | 1.84 (1.78 to 1.90) |

| 1996–2000 | 2740 | 1413 | 1.94 (1.87 to 2.01) |

*Adjusted for age and deprivation category (Carstairs 1991 decile) at first diagnosis.

Discussion

Main findings

This large national study provides an accurate estimate of the risk of early death experienced by adults previously hospitalised for mental disorder. We showed that the overall life expectancy for the whole cohort of individuals previously hospitalised due to mental ill health was 17 years less than that for the general population. The excess risk of early death was greatest for patients first admitted at the youngest age (15–19 years old), but individuals first admitted at older ages experienced greater numbers of early deaths. The largest reduction in life expectancy was seen for individuals with eating disorders and personality disorders—namely an alarming 39 years reduction in life expectancy for uncomplicated eating disorders, and 27.5 for those with a complicated personality disorder. However, as the greatest number of deaths was seen in individuals with depression and schizophrenia, these conditions accounted for the greatest number of YLL.

The majority of deaths in those previously hospitalised for mental disorder are due to ‘natural’ causes such as cardiovascular and respiratory disorder, which mirrors the results of a similar study from Denmark6 examining the life expectancy of those with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. By contrast, although only 11% of deaths in our study population were attributable to ‘non-natural’ causes such as suicide, accidents and homicide, we found that these ‘non-natural’ causes carried a substantially higher comparative excess risk of early death—ranging between 27 years of lost life for depression and a staggering 49.5 years for eating disorders, emphasising that these non-natural deaths occur earlier than the more common natural causes of death. For the whole cohort of mentally ill individuals, those dying from non-natural causes lost, on average, almost 32 years of life, reinforcing the continuing need for national suicide prevention strategies.

Stable ‘mortality gap’

In addition, contrary to results elsewhere,7 13 we did not find any evidence that the difference in risk of death between the general population and the mentally disordered was worsening over time. In fact, we observed that this ‘mortality gap’ was stable over 25 years for all the common mental disorders, which offers some reassurance to claims that the mentally disordered have not benefited from improvements in public health.8 Nevertheless, our data indicate that there continues to be a need for monitoring the physical health of those with mental disorder, and in particular screening for cardiovascular disease.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of this study include the whole population coverage and the long time series, along with the demonstrable high quality and completeness20 of the diagnostic coding and cause of death coding. The reliability of a given diagnosis does not necessarily imply that it is valid, however, in a specialty that lacks objective diagnostic tests. We have also taken care with main psychiatric diagnosis assignation, using a pragmatic hierarchical approach to account for the diagnostic shift and comorbidities that are commonly seen in day-to-day clinical psychiatric practice. Definitive diagnosis is not always easy initially in mental health, and over such a long study period there may be a shift in diagnostic trends. Main psychiatric diagnosis has therefore been assigned using a hierarchical approach and taking into account all diagnoses recorded on an individual's psychiatric discharge records over the period of study rather than simply diagnosis at first admission. This approach considerably increases the number of people in the higher categories (eg, psychoses). For example, of 17 031 individuals who were first admitted with depression, 71% were assigned to depression, 17% subsequently had schizophrenia recorded on a discharge record and so were assigned to ‘complicated schizophrenia’ and 11% were assigned to ‘complicated bipolar’. For some groups, the hierarchy is less intuitive, for example, of the 325 individuals who were first admitted with eating disorders but subsequently had other mental ill-health problems, 69% moved out of the eating disorder group into another group higher up the hierarchy (data not shown). This will lead to a conservative SMR for some complicated cases due to time at risk for conditions lower down the hierarchy being assigned to a condition higher up the hierarchy in the person-year analysis. Another consideration to bear in mind is that the threshold for admission to a psychiatric hospital will likely have changed over time, particularly, as community-based alternatives became available. This unquantifiable threshold shift could complicate the interpretation of the time trend data in table 6.

Comorbidity and early death

Furthermore, we have documented that diagnostic 'complexity’ (indicated by further recording of other mental disorders in addition to the main psychiatric diagnosis, substance misuse or physical health problems) tends to increase the risk of premature death and the average years of lost life in those previously hospitalised due to mental illness. This adverse effect of complexity has not been reported before to the best of our knowledge, and emphasises that comorbidity exacerbates prognosis, although an alternate explanation is that increased ‘complexity’ is in effect a proxy for lesser diagnostic rigour and care, which may in turn affect mortality. Similarly, an increased ‘complexity’ in a case may be a marker of increased severity of illness, which may in turn be related to early death. Also, our use of the SMR and the ‘years of lost life’ techniques allows the quantification of both the relative and the absolute burden of excess death in this population. However, as this is a secondary care cohort, it will only capture those most severely affected by mental disorder, and hence does not allow comment on, for example, those with depression managed solely in the community. Equally, those hospitalised due to eating disorder are often physically unwell, so it is perhaps no surprise that this diagnostic group had worrying relative and absolute mortality results in this study. Not all comorbidity (or ‘complexity’) will have been captured here, due to the exclusion of physical ill-health discharge records and probable under-recording of secondary psychiatric diagnostic codes. Finally, we designed a ‘wash in’ period of 5 years (1981–1986) in order to capture only first admissions, but it is likely that some patients with psychiatric admissions prior to 1981 were included. The apparently old age at ‘diagnosis’/first admission may suggest that these are in fact not all first admissions, that is, the relatively short wash in period has allowed us to include patients readmitted after more than 5 years as ‘first admissions’.

A systematic review by Saha et al13 found an SMR of 2.5 for risk of death in schizophrenia, which is greater than our figures of 1.8 (uncomplicated) and 2.0 (complicated), but the more recent study by Hoang et al7 from England found similar SMRs for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder to our own results, albeit with a shorter follow-up. Large long-term follow-up mortality studies comparing common mental disorders have not been reported elsewhere, to our knowledge, and our data provide the context for the literature on early death in specific disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,7 and depression and anxiety.21 More detailed analysis of the time trends for individual causes of death in specific diagnostic groups would be valuable in the future.

Implications

In previous studies of all-cause mortality in those with mental illness in Scotland, behavioural risk factors such as heavy smoking and a sedentary lifestyle have been linked to early death, along with social isolation and deprivation.22 Policy makers in the UK have also highlighted the physical health needs and premature mortality of those with mental health problems which echo the worrying disparities in lifespan we have identified for all the common mental disorders compared with the general population. In particular, we have found that the highest risk of early death is associated with young age at first admission; eating disorders; personality disorders; and in those with multiple diagnoses. A national approach across primary and secondary care tackling the complex mix of factors contributing to early death in the mentally disordered is required, addressing intrinsic disease-related factors as well as lifestyle issues; lack of help seeking; and even stigma within the healthcare professions.23 24 The inequity in life expectancy in the mentally disordered documented here poses a considerable challenge to our healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Denise Coia.

Footnotes

Contributors: OA and MT conceived and designed the study. OA and DS ascertained the data and prepared the results tables and graphs. All authors analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. RW is the study guarantor.

Funding: The funding was through NHS Scotland.

Competing interests: All authors are employed by NHS Scotland. MT has received fees and/or hospitality from the manufacturers of various antipsychotic medications.

Ethics approval: Neither NHS ethical approval nor Privacy Advisory Committee approval was required for this study as no patient identifiable data were released out with NHS National Services Scotland and no new data linkages were undertaken.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We are happy to share data with appropriate bodies and researchers.

References

- 1.Lopez AD, Murray C, C.J.L. The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med 1998;4:1241–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173:11–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Nordentoft M, et al. Increased mortality among patients admitted with major psychiatric disorders: a register based study comparing mortality in unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:899–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahlbeck K, Westerman J, Nordentoft M, et al. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:453–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, et al. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:116–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res 2011;131:101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoang U, Stewart R, Goldacre MJ. Mortality after hospital discharge for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: retrospective study of linked English hospital episode statistics, 1999–2006. BMJ 2011;343:d5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornicroft G. Physical health disparities and mental illness: the scandal of premature mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:441–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark C, Macleod M, Hall D, et al. Mortality after discharge from long term psychiatric care in Scotland, 1977–94: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2003;3:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang C, Hayes R, Perera G, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e19590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24:17–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborn DPJ, Levy G, Nazareth I, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom's General Practice Research Database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:242–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1123–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fors BM, Isacson D, Bingefors K, et al. Mortality among persons with schizophrenia in Sweden: an epidemiological study. Nord J Psychiatry 2007;61:252–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kendrick S, Clarke J. The Scottish record linkage system. Health Bull 1993;51:72–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming M, Kirkby B, Penny KI. Record linkage in Scotland and its applications to health research. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:2711–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLoone P. Carstairs scores for Scottish postcode sectors from the 1991 census. Glasgow: Public Health Research Unit, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Exeter D, Boyle P, Feng Z, et al. The creation of ‘consistent areas through time’ (CATTs) in Scotland, 1981–2001. Popul Trends 2005;119:28–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang CL. The life table and its applications. Malabar, Florida: Robert E Kreiger Publications, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 20. http://www.isdscotland.org/Products-and-Services/Data-Quality/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markkula N, Harkanen T, Perala J, et al. Mortality in people with depressive, anxiety and alcohol use disorders in Finland. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Steptoe A. Psychiatric hospital admissions, behavioural risk factors, and all cause mortality. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2474–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Agerbo E, et al. Somatic hospital contacts, invasive cardiac procedures, and mortality from heart disease in patients with severe mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:713–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence DM, Holman CD, Jablensky AV, et al. Death rate from ischaemic heart disease in Western Australian psychiatric patients 1980–1998. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:31–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.