Summary

Background and objectives

Patients with kidney failure sometimes do not receive chronic renal replacement therapy (RRT), even though this may reduce their life expectancy. This study aimed to identify factors associated with initiation of chronic RRT.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This cohort study was conducted with Albertans aged >18 years between May 2002 and March 2009, using linked data from the provincial renal programs, clinical laboratories, and provincial health ministry. This study focused on those who developed kidney failure, defined by an estimated GFR (eGFR) <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at last measurement during follow-up, together with prior CKD (eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at least 90 days earlier). Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine factors significantly associated with initiation of chronic RRT.

Results

In total, 7901 participants had eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at last measurement. After adjustment, older participants were less likely to initiate chronic RRT. Remote residence location, dementia, and metastatic cancer also decreased the likelihood of initiating RRT. The cumulative probability of initiating RRT during follow-up was 76.8% for urban-dwelling men aged <50 years without comorbidity, but was only 3.2% among remote-dwelling women aged ≥70 years with dementia and metastatic cancer. In contrast, patients with diabetes and heavy/severe proteinuria were more likely to initiate chronic RRT.

Conclusions

There is substantial variability in the likelihood of RRT initiation for patients with eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Further studies are needed to delineate factors that influence this outcome.

Introduction

Current guidelines define kidney failure by estimated GFR (eGFR) <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (1–3). Chronic dialysis is associated with high mortality rates (4,5), and many patients have poor quality of life (6–13). Although dialysis treatment is available to all Canadian residents (14), some people with kidney failure die without receiving dialysis or pre-emptive kidney transplantation (15–17), either because of unexpected death from comorbidity (18) or because of a deliberate choice not to receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) (19,20).

Not all patients with severe kidney disease develop clinical indications for RRT despite low eGFR, and some may choose not to initiate RRT even if treatment is medically indicated. Most studies of people with kidney failure focus on those initiating chronic RRT; much less is known about people who die without receiving RRT despite eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (untreated kidney failure). This issue is clinically important because choosing to forego RRT is a valid treatment option among competent and well informed patients.

We studied a large cohort of patients from a single Canadian province to assess the frequency of untreated kidney failure, and to examine factors that are associated with the occurrence of this outcome. Because patients with severe comorbidity (with poor life expectancy with or without dialysis) may experience less clinical benefit from RRT than healthier patients, we hypothesized that increased comorbidity would be associated with increased likelihood of untreated kidney failure. Similarly, because the burden associated with traveling to dialysis treatments (or relocation to a center with a dialysis unit) may be increased for people living far from the closest dialysis unit, we hypothesized that initiating RRT would be less common in remote-dwellers.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

We used the Alberta Kidney Disease Network database, which incorporates data from Alberta Health and Wellness (AHW; the provincial health ministry), the Northern and Southern Alberta Renal Programs, and the clinical laboratories in Alberta (21). We assembled a cohort of adults aged ≥18 years who were Alberta residents between May 2002 and March 2009, and who had serum creatinine measured during this period. All people registered with AHW were eligible for inclusion. All Alberta residents are eligible for insurance coverage by AHW, and >99% participate in this coverage. AHW coverage fully reimburses the cost of dialysis treatment, inpatient and outpatient medical costs, physician visits, and laboratory testing, including diagnostic imaging.

Population

We excluded patients with kidney failure (defined as documented eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, chronic dialysis, or prior kidney transplant) at baseline. Initiation of chronic dialysis and pre-emptive kidney transplantation (collectively comprising RRT) was identified using data from the Northern and Southern Alberta Renal Programs. The study population was further limited to those who developed kidney failure in follow-up. CKD was defined by at least two measurements of eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 >90 days apart with no interceding values ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Of these, we selected the subset with kidney failure, defined by eGFR measurement <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at end of follow-up (meaning that those whose eGFR declined below 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 but then recovered by end of follow-up were not considered to have experienced kidney failure). For this subset, the date where eGFR was first <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was considered the index date (Supplemental Figure 1). Only outpatient serum creatinine measurements were used, and GFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (22). Using the last measurement of proteinuria obtained before the index eGFR measurement, heavy/severe proteinuria was defined as urinary albumin/creatinine ratio ≥60 mg/mmol, protein/creatinine ratio ≥100 mg/mmol, or urine dipstick ≥2+. Patients in whom proteinuria was not measured before the index eGFR measurement were identified using a binary variable for “proteinuria not measured.”

We followed patients from the first occurrence of kidney failure after baseline until March 2009. Participants were categorized into the following outcome groups based on their clinical outcome at the end of study: chronic RRT, death, or neither (censored). The objective of this study was to identify factors associated with chronic RRT (“treated kidney failure”) compared with death in the absence of chronic RRT (“untreated kidney failure”).

Comorbidities

Demographic variables included age (categorized as 18–49.9, 50–69.9, and ≥70 years), sex, Aboriginal (registered First Nations or recognized Inuit), social assistance, rural or urban residence (defined using the Statistics Canada definition as recorded in the Postal-Code Conversion File data; www.statcan.ca), and distance to the closest nephrologist (categorized as ≤50, 50.1–100, 100.1–200, >200 km). Distance by road between the residence of each patient and the practice location of the closest nephrologist was calculated using ArcGIS 9.3 software (www.esri.com) as previously described (23).

We used validated algorithms to define the Charlson comorbidities, diabetes, and hypertension (24) at baseline using physician claims, hospitalization, and ambulatory care utilization data. The Charlson score was based on the Deyo classification (25) of the following comorbidities: cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, diabetes with and without complications, AIDS/HIV, metastatic solid tumor, myocardial infarction, mild liver disease, moderate/severe liver disease, paralysis, peptic ulcer disease, and rheumatic disease. We used International Classification of Diseases claims to define affective and psychotic disorders as in our previous work (26). The Charlson comorbidity variables were defined using all available claim and hospitalization data in the 3-year period before and on the index date (these data were available for >96% of the cohort). Diabetes and hypertension was defined using data 1 year before and on the index date and proteinuria was defined as the first value before and on the index date.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted analyses with Stata/MP 11.2 software (www.stata.com) and reported baseline descriptive statistics as counts and percentages, or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate. Chi-squared and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test for differences across outcome groups. Using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models (cause-specific hazard model), we estimated the associations between potential factors (at baseline) and initiation of chronic RRT adjusted for all variables presented in Table 1 including individual comorbidities but not the Charlson score. A two-way interaction between age and sex was also included. In alternative models, we explored two-way interactions between age and proteinuria as well as between age and diabetes, but these two-way interactions were not included in the main model. We censored follow-up when a participant died (competing risk), moved out of province, or reached the end of the study (March 31, 2009). Furthermore, we modeled death using a cause-specific Cox regression in which initiation of chronic RRT was treated as a competing risk; we considered a proportional subdistribution hazard model for modeling initiation of chronic RRT (27,28). In a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated factors associated with initiation of RRT in a subset of participants who experienced a more restrictive definition of kidney failure (eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2) at end of follow-up. In a second sensitivity analysis, we excluded participants who died within 6 weeks of the first documented instance of eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 without receiving RRT. We determined that the proportional hazard assumption was satisfied by examining plots of Schoenfeld residuals and testing covariates interacted with time. The threshold P for statistical significance was set at 0.05. The primary model used all available follow-up for each participant. In addition to hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), we present likelihoods of RRT initiation (drawn from the primary model) both after 1 year and at the end of follow-up. To calculate the likelihood of RRT initiation, we used estimates of the baseline survival function. In these analyses, other factors were assigned the population means or frequency, as appropriate. The institutional review boards at the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary approved this study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with kidney failure

| Characteristic | Study Endpoint | P Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiated Chronic RRT | Died | Censored | ||

| Participants | 1997 (25) | 3372 (43) | 2532 (32) | — |

| Follow-up (mo) | 7.2 (2.5, 16.3)b | 5.2 (0.9, 15.8) | 19.8 (8.4, 38.2) | — |

| Age (yr) | 65 (53, 74) | 83 (76, 89) | 76 (66, 83) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1198 (60) | 1429 (42.4) | 1066 (42.1) | <0.001 |

| Aboriginal | 140 (7) | 68 (2) | 53 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Social assistance | 205 (10.3) | 54 (1.6) | 103 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 322 (16.1) | 499 (14.8) | 394 (15.6) | 0.19 |

| Distance (km) | 20 (20, 60) | 20 (20, 80) | 20 (20, 80) | 0.002 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 1091 (54.6) | 1493 (44.3) | 1177 (46.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1808 (90.5) | 2990 (88.7) | 2334 (92.2) | 0.03 |

| Charlson scorec | 4 (2, 6) | 5 (3, 7) | 4 (2, 5) | <0.001 |

| AIDS/HIV | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | — |

| Cancer, metastatic | 36 (1.8) | 317 (9.4) | 72 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Cancer, nonmetastatic | 261 (13.1) | 884 (26.2) | 407 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 228 (11.4) | 794 (23.5) | 341 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 517 (25.9) | 1410 (41.8) | 758 (29.9) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 49 (2.5) | 988 (29.3) | 260 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 587 (29.4) | 1992 (59.1) | 908 (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Mild liver disease | 79 (4) | 89 (2.6) | 82 (3.2) | 0.01 |

| Mod/severe liver disease | 19 (1) | 58 (1.7) | 20 (0.8) | 0.02 |

| Myocardial infarction | 338 (16.9) | 944 (28) | 454 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 45 (2.3) | 112 (3.3) | 44 (1.7) | 0.03 |

| Peptic ulcer | 154 (7.7) | 305 (9) | 149 (5.9) | 0.09 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 275 (13.8) | 621 (18.4) | 339 (13.4) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 89 (4.5) | 167 (5) | 122 (4.8) | 0.41 |

| Affective disorder | 391 (19.6) | 734 (21.8) | 584 (23.1) | 0.06 |

| Psychotic disorder | 49 (2.5) | 206 (6.1) | 90 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria | <0.001 | |||

| Heavy/severe | 1175 (58.8) | 803 (23.8) | 694 (27.4) | |

| None/mild/moderate | 518 (25.9) | 1960 (58.1) | 1657 (65.4) | |

| Not measured | 304 (15.2) | 609 (18.1) | 181 (7.1) | |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range). RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Comparison of the group that initiated chronic dialysis with the group that died during follow-up.

If followed until end of study, death, or moving, then follow-up is 48.1 (29.6, 63.5).

Charlson score includes AIDS/HIV, metastatic cancers, nonmetastatic cancers, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, dementia, diabetes, heart failure, mild liver disease, moderate/severe liver disease, myocardial infarction, paraplegia, peptic ulcer, peripheral vascular disease, and rheumatologic disease. The median and interquartile range are presented.

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

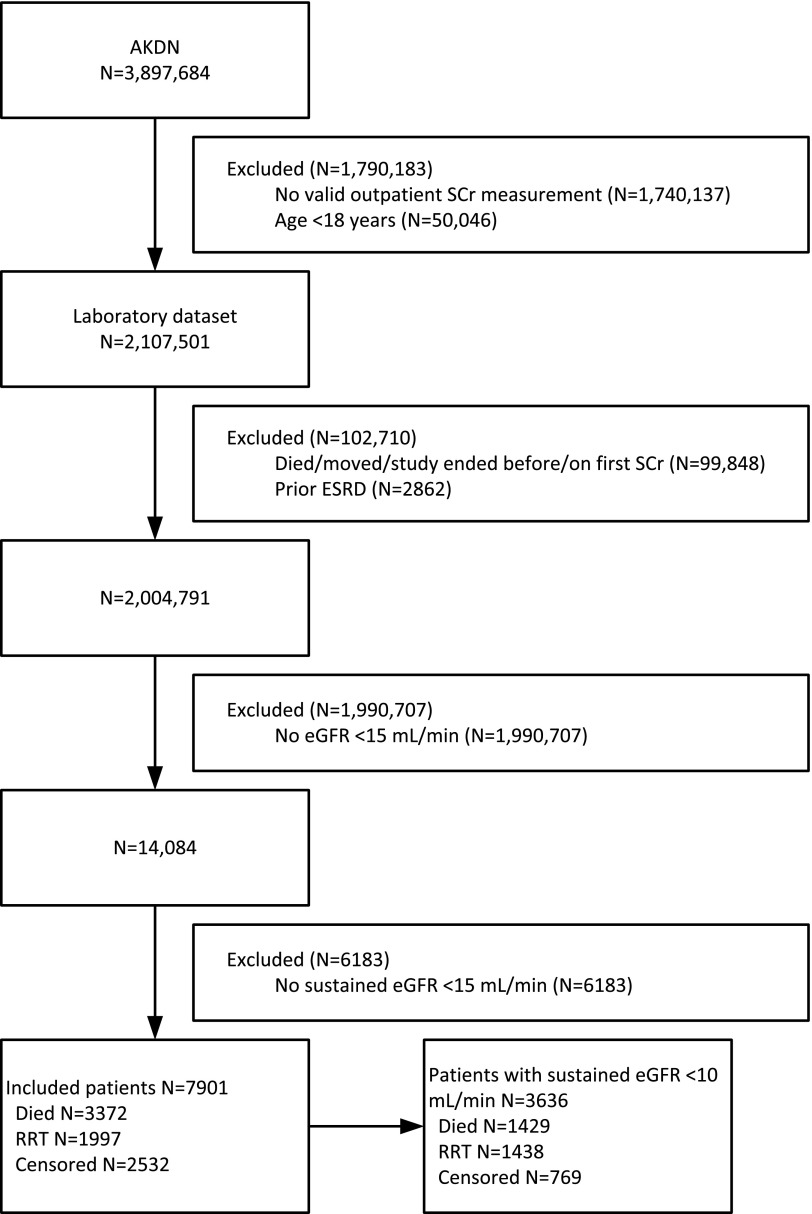

Of 3,897,684 potentially eligible participants, 7901 had eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at last measurement during follow-up and were selected for further study (Figure 1). During median follow-up of 11 months (IQR, 3–27 months), 1929 (24%) participants initiated chronic dialysis, 68 (1%) received a pre-emptive kidney transplant, 3372 (43%) died without initiating RRT, and the remaining 2532 (32%) were censored (neither died nor initiated RRT at end of follow-up). For purposes of analysis, patients initiating chronic dialysis and the small number who received a pre-emptive transplant were considered together.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram. CKD was defined by at least two measurements of eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 ≥90 days apart with no interceding values ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Of these, we selected the subset whose last eGFR measurement was <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2. For this subset, the date where eGFR was first <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was considered as the index date for kidney failure. AKDN, Alberta Kidney Disease Network; SCr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated GFR; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

The characteristics of the study participants who initiated chronic RRT, who died, or who were censored at the end of the study are shown in Table 1. Compared with those participants who died, participants who initiated chronic RRT were younger, were more often men and Aboriginal, were more often on social assistance, and were less likely to live in a remote location. Comorbidities were generally less common among patients who initiated chronic RRT compared with those who died—with the exception of diabetes, hypertension, and mild liver disease, which were more common in the former group.

Factors Associated with Initiating Chronic RRT

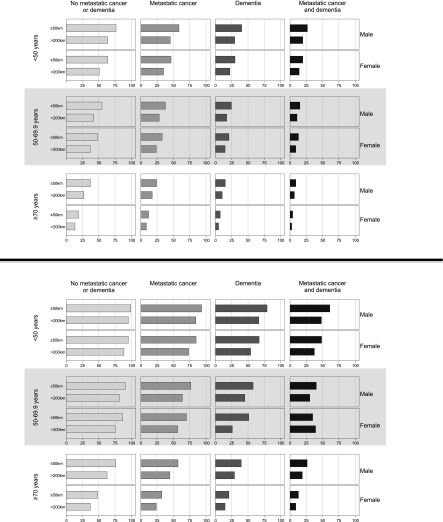

Older age, female sex, remote residence location, dementia, metastatic cancer, and chronic lung disease were all significantly associated with a lower likelihood of initiating chronic RRT, whereas the presence of heavy/severe proteinuria was associated with an increased likelihood of initiating chronic RRT. Even among people with diabetes, the presence of heavy/severe proteinuria increased the likelihood of RRT initiation during follow-up. For example, among urban men with diabetes aged 50–70 years, the likelihood of initiating RRT at 1 year after cohort entry was 50.2% and 20.4% for those with and without heavy/severe proteinuria, respectively (P<0.001).

The association between age and initiation of RRT was significantly modified by the presence of heavy/severe proteinuria (P<0.001). The HRs of initiating RRT were 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21 to 0.34) and 0.15 (95% CI, 0.12 to 0.19) for participants aged >70 with and without heavy/severe proteinuria, respectively (compared with participants aged 18–49.9, with and without heavy/severe proteinuria). Corresponding HRs for participants aged 50–69.9 years were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.57 to 0.89) and 0.52 (95% CI, 0.40 to 0.67).

The association between age and initiation of RRT was also modified by sex (P<0.001) (Table 2). Older women aged >70 years were less likely to initiate therapy than older men aged >70 years (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.54; P<0.001). Among groups defined by age, sex, and residence location, older women (aged ≥70 years) who lived >200 km from a nephrologist were the least likely to initiate chronic RRT (range, 0.9%–12.3% at 1 year of follow-up) and men aged <50 years who lived <50 km from a nephrologist (range, 8.5%–72.2% at 1 year of follow-up) were the most likely to initiate chronic RRT, regardless of their comorbidities (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 1). Results over the full duration of follow-up were similar.

Table 2.

Adjusted associations between potential factors and outcomes

| Factor | Initiated Chronic RRT | Initiated Chronic RRT, Sensitivitya | Initiated Chronic RRT, Sensitivityb | Died |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (n) | 1997 | 1438 | 1997 | 3372 |

| Men, age (yr) | ||||

| 18–49.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50–69.9 | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.64)c,d | 0.60 (0.49 to 0.73)c,d | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.65)c,d | 2.51 (1.48 to 4.25)c |

| ≥70 | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.38)c,d | 0.41 (0.33 to 0.50)c,d | 0.33 (0.28 to 0.39)c,d | 5.90 (3.52 to 9.88)c |

| Women, age (yr) | ||||

| 18–49.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50–69.9 | 0.64 (0.53 to 0.78)c,d | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.79)c,d | 0.64 (0.53 to 0.78)c,d | 2.07 (1.29 to 3.34)c |

| ≥70 | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.26)c,d | 0.27 (0.21 to 0.35)c,d | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.26)c,d | 4.81 (3.03 to 7.64)c |

| Aboriginal | 1.49 (1.23 to 1.81)c | 1.15 (0.92 to 1.45) | 1.48 (1.22 to 1.80)c | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.25) |

| Social assistance | 1.29 (1.10 to 1.50)c | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.30) | 1.29 (1.10 to 1.50)c | 1.13 (0.85 to 1.51) |

| Rural | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.25) | 1.05 (0.89 to 1.25) | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.26) | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.25)c |

| Distance (km) | ||||

| ≤50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50.1–100 | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.97)c,d | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.03) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.97)c,d | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.00) |

| 100.1–200 | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.94)c,d | 0.79 (0.63 to 0.99)c,d | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.94)c,d | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) |

| >200 | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.82)c,d | 0.71 (0.58 to 0.86)c,d | 0.69 (0.58 to 0.82)c,d | 1.08 (0.95 to 1.23) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.19 (1.08 to 1.31)c | 1.20 (1.07 to 1.34)c | 1.19 (1.08 to 1.31)c | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.01) |

| Hypertension | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.41)c | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.32) | 1.20 (1.02 to 1.40)c | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.66)c,d |

| Cancer, metastatic | 0.60 (0.43 to 0.85)c,d | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.98)c,d | 0.61 (0.43 to 0.86)c,d | 2.10 (1.85 to 2.39)c |

| Cancer, nonmetastatic | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.03) | 0.84 (0.71 to 0.99)c,d | 0.90 (0.79 to 1.04) | 1.38 (1.27 to 1.50)c |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.06) | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.06) | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.39)c |

| COPD | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98)c,d | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.91)c,d | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98)c,d | 1.17 (1.09 to 1.26)c |

| Dementia | 0.36 (0.27 to 0.47)c,d | 0.34 (0.25 to 0.46)c,d | 0.36 (0.27 to 0.48)c,d | 2.18 (2.01 to 2.36)c |

| Heart failure | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.02) | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.07) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.02) | 1.58 (1.46 to 1.70)c |

| Mild liver disease | 1.11 (0.89 to 1.39) | 1.15 (0.87 to 1.50) | 1.11 (0.88 to 1.39) | 0.89 (0.72 to 1.11) |

| Moderate/severe liver disease | 1.07 (0.67 to 1.69) | 0.74 (0.37 to 1.50) | 1.08 (0.68 to 1.71) | 1.87 (1.44 to 2.45)c |

| MI | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.10) | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.19) | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.11) | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.22)c |

| Paralysis | 1.11 (0.81 to 1.53) | 1.07 (0.72 to 1.59) | 1.11 (0.81 to 1.53) | 1.06 (0.87 to 1.29) |

| Peptic ulcer | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.44)c | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.25) | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.44)c | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.19) |

| PVD | 1.16 (1.01 to 1.33)c | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.18) | 1.17 (1.02 to 1.34)c | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) |

| Rheumatic disease | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.33) | 1.22 (0.95 to 1.57) | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.32) | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23) |

| Affective disorder | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.24) | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.27) | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.23) | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.95)c,d |

| Psychotic disorder | 0.75 (0.56 to 1.01) | 0.71 (0.50 to 1.00) | 0.77 (0.57 to 1.03) | 1.06 (0.92 to 1.23) |

| Proteinuria | ||||

| Heavy/severe | 3.06 (2.75 to 3.42)c | 2.30 (2.02 to 2.62)c | 3.08 (2.76 to 3.43)c | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.14) |

| Not measured | 2.28 (1.98 to 2.64)c | 1.67 (1.38 to 2.02)c | 2.30 (1.99 to 2.65)c | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.20) |

Data are presented as the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) unless otherwise specified. RRT renal replacement therapy; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; eGFR, estimated GFR.

Limited to participants with eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at last measurement during follow-up.

Excluded participants with early death (those who died within 6 weeks of first measured eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n=621).

Results significant at P<0.05.

Confidence limits that round to 1.00 may be >1.00 or <1.00; therefore, their significance status will vary. These results are significant but are associated with a lower likelihood of initiating chronic RRT.

Figure 2.

Proportion initiating chronic renal replacement therapy at the end of follow-up. The top and bottom panels are for patients without and with heavy/severe proteinuria, respectively. In each panel, the columns from left to right, light gray to black bars, show participants with less to more comorbidity, specifically no metastatic cancer or dementia, metastatic cancer, dementia, and both metastatic cancer and dementia. Plots of male and female participants alternate from the top to the bottom of the plot region. The first two rows are for participants aged <50 years, the second two rows are for participants aged 50–69.9 years (shaded), and the last two rows are for participants aged ≥70 years. Lastly, within each graph, the top bars show participants residing ≤50 km from a nephrologist and the bottom bars show participants residing >200 km from a nephrologist.

Participants who were Aboriginal, on social assistance, and who had diabetes, hypertension, a history of peptic ulcer disease, or prior peripheral vascular disease were more likely to initiate chronic RRT. Results for the proportional subdistribution hazard model were similar (data not shown) and are not presented.

Results were similar when eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at end of follow-up was used to define kidney failure. Specifically, the likelihood of initiating RRT was lower among those with older age, female sex, remote residence location, and increasing comorbidity, and higher among people with diabetes or heavy/severe proteinuria (Table 2).

In a second sensitivity analysis, we excluded participants who died within 6 weeks of the first documented instance of eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 without receiving RRT. In this analysis, all variables (older age, female sex, remote residence, metastatic cancer, chronic lung disease, and dementia) remained significantly associated with not initiating RRT (Table 2).

Factors Associated with Death

In addition to being associated with a lower likelihood of initiating chronic RRT, older age, metastatic cancer, dementia, and chronic lung disease were associated with significantly increased risk of death (Table 2). Male sex, rural residence, nonmetastatic cancer, heart failure, liver disease, cerebrovascular disease, and prior myocardial infarction were associated with increased risk of death.

Discussion

Although development of kidney failure defined by eGFR is an objective outcome, initiation of RRT is at least partially subjective because it requires a specific decision by the patient and his or her physician. In this study of roughly 4 million people treated in a universal health care system, we found substantial variation in the likelihood of RRT initiation. Older age, female sex, remote residence location, and comorbidities such as dementia, metastatic cancer, and chronic lung disease were independently associated with lower likelihood of initiating chronic RRT for kidney failure. There was substantial variability in the likelihood of initiating RRT by these factors; the cumulative incidence of RRT initiation among those with kidney failure was 76.8% for younger, urban-dwelling men without comorbidity, but only 3.2% among remote-dwelling women aged >70 years and with substantial comorbidity such as dementia and metastatic cancer. Results were consistent for two different statistical approaches and robust to sensitivity analysis in which patients with limited life expectancy were excluded.

Because follow-up in this study was relatively short (median of 11 months), some participants were censored (neither died nor experienced kidney failure during the study). Some of these participants may have had stable (or very slowly decreasing) kidney function despite their low baseline eGFR. This would have led to identification of factors that predispose to more rapid renal loss (such as diabetes and heavy/severe proteinuria) as being associated with RRT initiation. In support of this hypothesis, differences in the proportion initiating RRT between people with and without heavy/severe proteinuria were less pronounced after inclusion of follow-up beyond 1 year after first documentation of kidney failure. However, differences in rate of progression are unlikely to explain all of the observed heterogeneity in the proportion who initiated RRT during follow-up.

Why would patients with kidney failure not initiate RRT? Although there are limited data (15–17,29), there are at least four potential reasons: patients may intend to initiate RRT (especially dialysis) but die before treatment begins, they may choose not to receive RRT, they may not be offered RRT by providers, or they may not have a clinical indication for RRT despite very low eGFR. We attempted to reduce the likelihood that unexpected death influenced our results by excluding patients who died soon after first measurement of low eGFR (<10 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and found similar results. This suggests that unexpected death was not a major contributor to our results. Although a decision by nephrologists not to offer RRT to people with poor prognosis was relatively common 2 decades ago (30), clinical experience suggests that such unilateral decisions are rare in Canada today. However, because we did not have data on the reason that RRT was not initiated, these comments are speculative.

Previous studies of this issue tended to focus exclusively on patients aged >70 years (15,16,18) and generally compared survival and prognostic factors between patients receiving dialysis with those who opted for conservative management. Our findings were broadly similar to these previous studies, which identified a lower likelihood of dialysis initiation among female patients (30) and elderly individuals (31–34). Given the potential burden of repeated travel to receive dialysis treatment (and because dialysis was much more common than pre-emptive transplantation), it was not surprising that remote-dwelling patients were less likely to initiate RRT than those living closer. In fact, qualitative studies of patients with advanced kidney failure suggest that prolonged travel to a distant facility is an important potential barrier to accepting dialysis treatment (20,33,35,36). Our previous work shows that the likelihood of untreated kidney failure is substantially higher among older adults than in otherwise similar younger patients (37); this study extends these findings by highlighting how the likelihood of initiating RRT varies with the presence of other clinical characteristics including sex, comorbidity, and residence location.

A recent meta-analysis including >2 million participants showed that the strong association between albuminuria and the risk of ESRD (defined as dialysis initiation, kidney transplantation, or death due to kidney failure) was not significantly modified by age (38). Like Hallan et al. (38), we found that people with heavy albuminuria were more likely to initiate RRT. However, we also noted that the presence of albuminuria appeared to modify the relation between age and the likelihood of RRT initiation. Specifically, the decreased likelihood of initiating RRT among older people (versus younger people) was attenuated in the presence of heavy albuminuria.

Our study has limitations that should be considered. First, although we used validated algorithms to assess comorbidity, we relied on linkage of serum creatinine data with administrative databases to identify patients; thus, some patients with kidney failure might have been missed or the burden of comorbidity underestimated (39). In particular, participants who did not have serum creatinine measured before death would not have been identified as having kidney failure. However, because of the universal nature of health care in Canada, this was unlikely to have been a common occurrence. Second, we were not able to identify the race of participants other than Aboriginal, and thus could not examine how the likelihood of RRT initiation varied by race. Third, although we had eGFR data, we did not have information on symptom burden, quality of life, family supports, or patient preferences—all of which likely also influenced the decision to initiate dialysis, especially in elderly individuals (33,34,40). Fourth, our data were drawn from a single Canadian province, and whether our findings apply to other populations or settings will require further study. Fifth, the definition of untreated kidney failure that we used has some limitations. For example, some patients might have recovered kidney function with additional follow-up (thus misclassified as untreated kidney failure); others might have had eGFR values that were typically <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 but were ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at end of follow-up due to random fluctuations in serum creatinine (thus misclassified as free of kidney failure). However, results were similar when a more stringent definition of kidney failure was used (eGFR <10 ml/min per 1.73 m2), suggesting that these limitations are unlikely to have affected our conclusions. Finally, given the nature of our data, we could not exclude the possibility that some patients were not offered RRT by their providers, although we believed that this was unlikely to have occurred frequently during the study period.

Although RRT can be associated with good quality of life among patients with older age or more comorbidity (41–44), the choice not to receive RRT is entirely appropriate for competent, well informed patients. Physicians should focus on ensuring that patients with kidney failure are educated about their choices and the likely outcomes of the various treatments, including conservative management. The substantial variability in the likelihood of initiating RRT suggests the need for future studies to better understand the factors that influence this outcome, as well as the need for clinical tools that assist patients to make an appropriate, well informed decision that incorporates their values and preferences. Finally, our results justify continued efforts to improve access to tertiary services (including dialysis and pre-emptive kidney transplantation) for remote-dwellers.

In conclusion, we found substantial variability in the likelihood of initiating RRT for kidney failure in this population-based cohort study. Further work is needed to identify factors that influence this outcome and facilitate shared decision making about the benefits and harms of chronic RRT.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a team grant to the Interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) and by the University Hospital Foundation. M.T. is supported by an AHFMR Population Health Scholar award and a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal care of people with CKD.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.10721012/-/DCSupplemental.

See related editorial, “What Determines Whether a Patient Initiates Chronic Renal Replacement Therapy?,” on pages 1276–1278.

References

- 1.Levin A, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B, Tobe S, McFarlane P, Ruzicka M, Burns K, Manns B, White C, Madore F, Moist L, Klarenbach S, Barrett B, Foley R, Jindal K, Senior P, Pannu N, Shurraw S, Akbari A, Cohn A, Reslerova M, Deved V, Mendelssohn D, Nesrallah G, Kappel J, Tonelli M: Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease. CMAJ 179: 1154–1162, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions: Chronic Kidney Disease: National Clinical Guideline for Early Identification and Management in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care, London, Royal College of Physicians, The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Organ Replacement Register: Treatment of End-Stage Organ Failure in Canada: 1999 to 2008—CORR 2010 Annual Report, Ottawa, Ontario, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurm HS, Gore JM, Anderson FA, Jr, Wyman A, Fox KA, Steg PG, Eagle KA, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Investigators : Comparison of acute coronary syndrome in patients receiving versus not receiving chronic dialysis (from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE] Registry). Am J Cardiol 109: 19–25, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakewell AB, Higgins RM, Edmunds ME: Quality of life in peritoneal dialysis patients: Decline over time and association with clinical outcomes. Kidney Int 61: 239–248, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP, Jr, Hart LG, Blagg CR, Gutman RA, Hull AR, Lowrie EG: The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 312: 553–559, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N: A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int 50: 235–242, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manns B, Johnson JA, Taub K, Mortis G, Ghali WA, Donaldson C: Quality of life in patients treated with hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis: What are the important determinants? Clin Nephrol 60: 341–351, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, de Haan RJ, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT: Physical symptoms and quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: Results of The Netherlands Cooperative Study on Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD). Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 1163–1170, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suet-Ching WL: The quality of life for Hong Kong dialysis patients. J Adv Nurs 35: 218–227, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, Rotondi AJ, Cohen LM, Zeidel ML, Arnold RM: Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1345–1352, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wight JP, Edwards L, Brazier J, Walters S, Payne JN, Brown CB: The SF36 as an outcome measure of services for end stage renal failure. Qual Health Care 7: 209–221, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manns BJ, Mendelssohn DC, Taub KJ: The economics of end-stage renal disease care in Canada: Incentives and impact on delivery of care. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 7: 149–169, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A: Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1611–1619, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, Nguyen AT, Touam M, Grünfeld JP, Jungers P: Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: Cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1012–1021, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendelssohn DC, Kua BT, Singer PA: Referral for dialysis in Ontario. Arch Intern Med 155: 2473–2478, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, Rose J, Masterson R, Johnson DW, Howard K: Factors influencing patient choice of dialysis versus conservative care to treat end-stage kidney disease. CMAJ 184: E277–E283, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manns BJ, Mortis GP, Taub KJ, McLaughlin K, Donaldson C, Ghali WA: The Southern Alberta Renal Program database: A prototype for patient management and research initiatives. Clin Invest Med 24: 164–170, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rucker D, Hemmelgarn BR, Lin M, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW, Ayyalasomayajula B, James MT, Bello A, Gordon D, Jindal KK, Tonelli M: Quality of care and mortality are worse in chronic kidney disease patients living in remote areas. Kidney Int 79: 210–217, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan H, Khan N, Hemmelgarn BR, Tu K, Chen G, Campbell N, Hill MD, Ghali WA, McAlister FA, Hypertension Outcome and Surveillance Team of the Canadian Hypertension Education Programs : Validation of a case definition to define hypertension using administrative data. Hypertension 54: 1423–1428, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA: Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43: 1130–1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bresee LC, Tonelli M, Manns B, Hemmelgarn BH: Temporal trends in incidence of acute myocardial infarction and revascularization in people with and without mental illness. Presented at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention/Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism 2012 Scientific Sessions, San Diego, CA, March 13–16, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim HJ, Zhang X, Dyck R, Osgood N: Methods of competing risks analysis of end-stage renal disease and mortality among people with diabetes. BMC Med Res Methodol 10: 97, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns A, Davenport A: Maximum conservative management for patients with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Hemodial Int 14[Suppl 1]: S32–S37, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch DJ, West ML, Cohen AD, Jindal KK: Experience with not offering dialysis to patients with a poor prognosis. Am J Kidney Dis 23: 463–466, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez Jornet A, Ibeas J, Real J, Peña S, Martínez Ocaña JC, García García M: [Advance directives in chronic dialysis patients]. Nefrologia 27: 581–592, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K: Choosing not to dialyse: Evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract 95: c40–c46, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Visser A, Dijkstra GJ, Kuiper D, de Jong PE, Franssen CF, Gansevoort RT, Izaks GJ, Jager KJ, Reijneveld SA: Accepting or declining dialysis: Considerations taken into account by elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. J Nephrol 22: 794–799, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yong DS, Kwok AO, Wong DM, Suen MH, Chen WT, Tse DM: Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: A study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med 23: 111–119, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fetherstonhaugh DMA: Hobson's Choice: Dialysis or the Coffin: A Study of Dialysis Decision-Making Amongst Older People [PhD thesis], Melbourne, Australia, Centre for Health and Society and the Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnston S, Noble H: Factors influencing patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease to opt for conservative management: A practitioner research study. J Clin Nurs 21: 1215–1222, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Manns BJ, O’Hare AM, Muntner P, Ravani P, Quinn RR, Turin TC, Tan Z, Tonelli M, Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Rates of treated and untreated kidney failure in older vs younger adults. JAMA 307: 2507–2515, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hallan SI, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Mahmoodi BK, Black C, Ishani A, Kleefstra N, Naimark D, Roderick P, Tonelli M, Wetzels JF, Astor BC, Gansevoort RT, Levin A, Wen CP, Coresh J, Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Age and association of kidney measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease. JAMA 308: 2349–2360, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Martin AA, Fink NE, Powe NR: Validation of comorbid conditions on the end-stage renal disease medical evidence report: The CHOICE study. Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 520–529, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo WK, Li FK, Choy CB, Cheng SW, Chu WL, Ng SY, Lo CY, Lui SL: A retrospective survey of attitudes toward acceptance of peritoneal dialysis in Chinese end-stage renal failure patients in Hong Kong—from a cultural point of view. Perit Dial Int 21[Suppl 3]: S318–S321, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chester AC, Rakowski TA, Argy WP, Jr, Giacalone A, Schreiner GE: Hemodialysis in the eighth and ninth decades of life. Arch Intern Med 139: 1001–1005, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimkovic N, Oreopoulos DG: Chronic peritoneal dialysis in the elderly. Semin Dial 15: 94–97, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kutner NG, Jassal SV: Quality of life and rehabilitation of elderly dialysis patients. Semin Dial 15: 107–112, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westlie L, Umen A, Nestrud S, Kjellstrand CM: Mortality, morbidity, and life satisfaction in the very old dialysis patient. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 30: 21–30, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.