Summary

Nephrologists have focused on the uremic syndrome as an indication for dialysis. The elderly frail renal patient approaching ESRD represents a complex biologic system that is already failing. This patient phenotype exhibits progressive geriatric disabilities and dependence interspersed with shrinking periods of stability regardless of whether dialysis is started. Consequently, the frail renal patient faces challenging treatment choices underpinned by ethical tensions. Identifying the advanced frail renal patient and optimizing the shared decision-making process will enable him or her to make well informed choices based on an understanding of his or her overall condition and personal values and preferences. This approach will also permit nephrologists to fulfill their ethical obligations to respect patient autonomy, promote patient benefit, and minimize patient harm.

Introduction

The renal community is grappling with an explosion of CKD stage 4–5 patients over the age of 80 years with a spectrum of comorbidities and geriatric syndromes, including frailty, who bring expectations and misconceptions about what dialysis as a life-sustaining and quality of life therapy may achieve. Dialysis has become routine practice in the current environment of procedure-driven medical care and biomedicalization of aging, which has made it challenging for patients, families, and health professionals to make true choices (1). There are guidelines for situations where it is appropriate to forgo dialysis, like irreversible coma, terminal cancer, or inability to tolerate the procedure (2). However, there is also a growing group of elderly frail renal patients who have no absolute contraindications to renal replacement but are at risk for early mortality, increased hospitalizations, acceleration of geriatric syndromes, and significant symptom burden. Because medical care of the seriously ill patient by technology has become a major focus for ethical judgments about life, longevity, and how love and caring are expressed (1,3), patients and families struggle with saying no to dialysis therapy and yes to nondialysis medical therapy, although medical indications, big picture goals, and quality of life reasons for choosing the latter may be compelling. Shared decision-making, which includes informing the patient about the prognosis, dialysis trajectory, and nondialysis medical therapy; exploring patient values and preferences; and making an appropriate recommendation, could improve ESRD treatment choices and uphold the ethical principles that support the practice of medicine. The purpose of this article is to

examine the consequences of frailty for the elderly patient with renal disease,

describe the frail renal phenotype as a screening tool to identify the advanced frail patient, and

review ethical considerations involved in helping the advanced frail patient facing dialysis make good choices.

Frailty in Older ESRD Patients

A recent study (4) using Medicare data from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) looked at the intensity of care in the last month of life in 93,329 patients 65 years and older who initiated chronic dialysis and then died over a 5-year period. Compared with similar data in cancer and heart failure patients, those patients on dialysis had more hospitalizations (76 versus 61.3, 64.2%), intensive care unit admissions (48.9 versus 24, 19%), and hospital deaths (44.8 versus 29, 35.2%) and less hospice use (20 versus 55, 39%). The mean hospital stay was 9.8 days, and 29% underwent at least one life-sustaining intervention, including mechanical ventilation (22.3%), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (11.9%), and feeding tube placement (3.9%), before death. Use of these procedures did not differ significantly by sex, cause of ESRD, comorbid illness, or duration of dialysis and were more common in African Americans and those patients who died from cardiovascular causes.

The average first-year mortality in dialysis patients over the age of 80 years can approach 46%, and it can be 58% in nursing home patients who initiate dialysis while in long-term care (5,6). Up to 34% of elderly patients will withdraw from renal replacement therapy compared with 20% in the general dialysis population (7).

Because frailty is common in the CKD and dialysis (8–10) populations, a significant proportion of older ESRD patients may have advanced frailty at the end of life (EOL). Frailty starts early in CKD and is an independent risk factor for death and hospitalization (8–10). The prevalence of frailty in the CKD population is approximately two times the prevalence in a general geriatric outpatient community (14%–15% versus 6%–7%) (9,10). Frailty increases as estimated GFR (eGFR) declines, with an adjusted prevalence that is 2.1- and 2.8-fold greater for eGFR values of 30–44 and <30, respectively, compared with an eGFR of >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and it is associated with an estimated 2.5-fold (95% confidence interval [95% CI]=1.4 to 4.4) greater risk of death or dialysis therapy (10). This result might explain the findings in a Veterans Administration study of CKD patients ≥85 years who were more likely to die than be treated with dialysis for ESRD (11). Frailty increases as much as fivefold in dialysis patients and is independently associated with a higher risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]=2.24, 95% CI=1.60 to 3.15) and combined outcome of death or hospitalization (adjusted HR=1.63, 95% CI=1.41 to 1.87) (8). A recent study found that frailty was associated with starting dialysis at a higher eGFR as well as increased mortality, which was attenuated when this latter finding was corrected for frailty (12). This finding suggests that the symptoms and signs of frailty may be mistaken for or overlap with the signs of uremia and would then contribute to the poor outcomes in subgroups of elderly dialysis patients (Table 1), whereas traditional kidney quality indicators meet performance targets.

Table 1.

Mean life expectancy by quartile following dialysis initiation according to age and renal phenotype

| Renal Phenotype Quartiles | Life Expectancy by Age Group (yrs) | |||||

| 65–69 | 70–74 | 75–79 | 80–84 | 85–89 | 90+ | |

| 25th Percentile (0–25; frail) | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 50th Percentile (25–75; vulnerable) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| 75th Percentile (75–100; healthy) | 4.6 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 1.7 |

Adapted from reference 33, with permission.

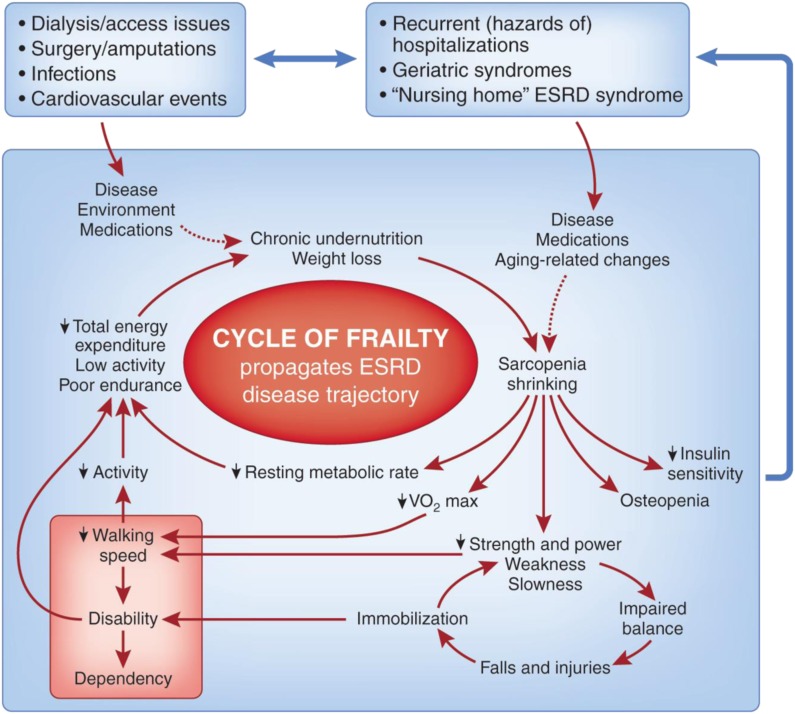

Like the unrecognized symptoms and palliative care needs (13) of ESRD patients, frailty is underdiagnosed and undertreated, in part because of the lack of a uniform definition and diagnostic criteria (14). Because this biologic entity has significant ramifications and provides a formidable opponent to quality of life, it is an ethical imperative for the renal community to understand, recognize, and be transparent about the Cycle of Frailty (see below and Figure 1) that impels certain subgroups of advanced CKD and dialysis patients to the EOL experiences described above with a high potential for suffering. This sober view must frame information sharing and recommendations in the dialysis decision-making process. The revised 2010 Renal Physicians Association guideline on the appropriate initiation and withdrawal of dialysis (2,15) provides guidance in shared decision-making, advance care planning, prognosis evaluation, and palliative care and has been shown to be effective in improving nephrologists’ preparedness in EOL decision-making (16).

Figure 1.

Cycle of Frailty with trigger entry point health events. Reprinted from reference 28, with permission.

Consequences of Frailty for the Elderly Patient with Renal Disease

The geriatric syndrome of frailty is a biologic wasting syndrome of older adults that spans multiple physiologic systems, is characterized by decreased reserves, resistance to stressors, sarcopenia, protein energy malnutrition, and atherosclerosis, and is predictive of disability, hospitalization, and mortality in community elders (17,18). Frailty is associated with increased inflammatory biomarkers (18,19). Recently, a frail mouse model has been characterized (20,21) that confirms the role of inflammatory pathway activation in this syndrome. Uremia and the dialysis procedure provide microinflammatory and oxidant stress environments (22,23) that may accelerate the expression and progression of frailty in predisposed subsets of the geriatric renal population.

Frailty is a risk factor for disability and comorbidity but may exist independently of both (17). A useful conceptual model is the Cycle of Frailty (24) (Figure 1) that is activated through trigger points of entry by intervening health events and continues to recycle after the event has terminated. At 6 months after an episode of septicemia or long bone fracture, dialysis patients have adjusted relative risks of death of 7.1 and 3.2, respectively, compared with a reference nonevent (no septicemia or long bone fracture) dialysis population (25). As the number of acute health events increases, the frailty cycle will accelerate to its end points of dependence, disability, and death.

The Cardiovascular Health Study, a longitudinal observational study in a geriatric outpatient ≥65-years-old patients community, operationalized a frailty clinical tool or frailty phenotype comprising five components: unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, low physical activity, slow gait, and weakness; a positive test requires the presence of at least three of five components, and one to two of five components signifies a prefrail state (17). The frailty phenotype had an overall prevalence of 6.9% (16.3% in those patients 80–84 years old and 25.7% in those patients 85–89 years old), with a 4-year incidence of 7.2%. It was an independent predictor (HRs estimated over 3 years in parentheses; all significance levels at P<0.05) for incident falls (1.29), worsening mobility (1.50), Activities of Daily Living (ADL) disability (1.98), hospitalization (1.29), and death (2.24). Of those patients who tested positive for frailty, 27% had neither ADL disability nor comorbidity (two or more comorbidities). Additionally, those patients who were prefrail at baseline (46.6%) had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.63 of becoming frail in the next 3–4 years compared with those patients who had no frailty components (17). It must be emphasized that the operational definition of frailty varies widely according to the conceptual framework, and no gold standard exists (14,26).

At what point does frailty become advanced or irreversible? Like the EOL concept (27,28), frailty can be viewed as a spectrum diagnosed by clinician assessment and prognostic tools (see below). The Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale (29) defines moderately frail as needing help with both ADLs and instrumental ADLs and severely frail as being completely dependent on others for ADLs or terminally ill. Alternatively, the presence of recurrent falls, increasing disability, and snowballing episodes of acute illness with incomplete recovery might suggest the presence of end stage frailty (14). Although there are no curative options for the frailty syndrome, targeted exercise and ongoing geriatric evaluation may improve clinical outcomes (14). A positive effect on ADL and instrumental ADL disability has usually required relatively long-lasting and intensive multicomponent exercise programs (30). There are no specific frailty intervention studies in ESRD patients, although geriatric renal rehabilitation programs have had success in improving functional disability (31). Elderly patients who initiate traditional dialysis will experience loss of independence at home and the need for increasing assistance (32). Dialysis also does not prevent functional decline in nursing home patients (6). These consequences may reflect aspects of progressing frailty, and if the patient is at an advanced stage of frailty, then interventions, including renal replacement, will not be successful in any significant and long-lasting way.

Frail Renal Phenotype: A Global Screening Tool to Identify the Frail Advanced Renal Patient

The frailty phenotype measure by Fried et al. (17) is a useful screening and research tool for physical frailty, but it does not incorporate other contributors to frailty, such as cognitive decline or comorbidities (26), which can drive the Cycle of Frailty. For any particular age group, dialysis patients can be divided into quartiles with differences in life expectancy (33) (Table 1). Parallel healthy (75th to 100th percentile), vulnerable (25th to 75th percentile), and frail (0 to 25th percentile) renal phenotypes have been described (Table 2) to improve decision-making and supportive/palliative renal management (28,34). The frail renal phenotype (Table 3) is a useful global construct that combines geriatric susceptibility factors (dementia, inability to ambulate, positive physical frailty testing, hypoalbuminemia, and significant symptom burden), survival data, and comorbidity information (2,34–38). Identifying this phenotype provides useful information relevant to the shared decision-making ESRD treatment discussion. Can this phenotype be considered an EOL diagnosis? Qualitatively, it can. Although the quantitative prognosis may be uncertain, it is important to implement an advance care plan (ACP) (34).

Table 2.

Healthy, vulnerable, and frail renal phenotypes with assessment tools

| Renal phenotypes |

| Healthy/usual |

| Most optimal dialysis patient |

| Might also be a transplant candidate |

| Vulnerable |

| More typical dialysis candidate |

| Characterized by increasing hospitalizations and unpredictable outcomes |

| Frail |

| Most susceptible to poor near-term outcome (6–12 months) |

| High risk of multiple and prolonged hospitalizations |

| Some are nursing home patients with marked functional disability, cognitive impairment, and dementia |

| Medical care decisions depend more on patient preferences and quality of life issues |

| Assessment tools |

| Geriatric susceptibility factors |

| Presence of dementia |

| Presence of frailty |

| Functional disability |

| Comorbidity |

| Modified Charleson comorbidity score (36) |

| Hemodialysis mortality predictor (35) |

| French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network 6-Month Prognosis Clinical Score (37) |

| Surprise question (38) |

| Nursing home patient syndrome (6) |

| Symptom burden assessment (13) |

Modified from reference 34, with permission.

Table 3.

Frail renal phenotype

| Karnofsky score<50 (disabled; requires special care and assistance) |

| Older age compared with 80–84 years: 85–89 years, RR=1.22 (95% CI=1.20 to 1.24); ≥90 years, RR=1.56 (95% CI=1.51 to 1.61) |

| Presence of geriatric susceptibility factors (syndromes) |

| Dementia |

| Nonambulatory status (RR=1.54, 95% CI=1.49 to 1.58) |

| Positive frailty testing |

| Serum albumin<35 g/L (RR=1.28, 95% CI=1.25 to 1.30) |

| Significant symptom burden |

| “Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” No |

| Low survival probabilities by |

| Comorbidity scores: CCI≥8 (36); FREIN clinical score≥9 (37) |

| Hemodialysis mortality predictor (35) |

| Four chronic conditions (RR=1.68, 95% CI=1.64 to 1.72) |

| Nursing home patient (6) |

The geriatric component of the frail renal phenotype includes functional disability, dementia, and frailty. Functional disability refers to limitations in mobility, ADLs, and/or instrumental ADLs, and it is associated with increased mortality, hospitalization, and long-term care independent of its cause (39). Inability to transfer is associated with a relative risk for death of 1.54 (5) and receives a high-ranking number on comorbidity scores (37).

Dementia diagnosed predialysis in advanced CKD is an independent risk factor for subsequent death and functional decline after dialysis is initiated. In a retrospective cohort study using USRDS data (40), the average time to death of patients with dementia before renal replacement who then started dialysis was 1.09 versus 2.7 years (P<0.001) for those patients without dementia, with a 2-year respective survival of 24% versus 66% (P<0.001) and an adjusted HR for death of 1.87 (95% CI=1.77 to 1.98). The dementia patients also experienced a threefold increase in the loss of ambulation and a greater than fourfold increase in the loss of transfer ability (both P<0.05). A marked increase in mortality in incident dialysis patients who have coexistent dementia and cannot ambulate has also been documented (7).

Ethical Considerations: Making Good Choices with the Advanced Frail Patient Facing Dialysis

The ethical clinical scenarios facing frail patients with advanced renal disease and patients on dialysis are framed by the principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice (41). Besides curing disease, the fundamental goals of medicine include the relief of suffering, treatment of symptoms, especially pain, maintenance of quality of life, communication about prognosis, and avoidance of harm (41). When patient goals are clear and one therapy option is superior, with significant benefits and small risks, no ethical dilemma exists; however, a conflict may arise when goals are not realistic or achievable and when benefits are outweighed by burdens (42). Dialysis has become one of many routine technology-based medical interventions commonly used in the elderly, and it exemplifies the successes of life extension but also, the responsibilities and burdens of medical choice placed on health practitioners, elderly patients, and their families (43). When counseling advanced CKD patients with a positive frail renal phenotype about dialysis versus nondialysis therapy, nephrologists must emphasize not only benefits, but also, they must speak clearly about possible negative consequences and offer recommendations for therapy that will either reflect patient values and preferences or serve the patient’s best interest if decisional capacity or prior wishes are absent (42).

Best interests are the set of elements that make up quality of life and involve the balance of the benefits to the burdens associated with the proposed treatment. They must be examined from the patient’s personal viewpoint and values, and they must take into account not only the disease conditions but also nonmedical factors, such as interpersonal relationships, resources, and social circumstances (41) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Promoting best interests of the frail renal phenotype

| Understand patient perspective in context of geriatric principles, personal history, values, and quality of life needs |

| Address misunderstandings and concerns |

| What do dialysis and nondialysis therapies involve? |

| What is the time and resource commitment? |

| What are the associated symptoms? |

| What will get better or continue to deteriorate? |

| Make recommendations based on prognostic data and goals of care |

| Negotiate a mutually acceptable plan |

Modified from reference 42, with permission.

It should be emphasized that the ethical principle of beneficence that underpins the best interests concept assumes that patients are vulnerable and medically uninformed, whereas patient autonomy implies an informed decision (42). Because both can coexist, physicians must advise patients and guide them away from unwise decisions (42), which means that the nephrologist should make a therapy recommendation but must also be prepared if the patient and family decide differently.

The patient preference issue is particularly important, because older patients may change their preferences for life-sustaining therapy depending on the particular clinical situation (44). Family members and physicians may also perceive patient wishes that are discordant with what the patient actually desires. In this regard, patients’ preferences for dialysis in different circumstances were incorrectly predicted by surrogates, family members, and their physicians up to one third of the time (45,46), with families consistently overestimating patients’ desires to continue dialysis across hypothetical health conditions. This discordance may lead to tension between patient preferences and best interests in the context of advanced frailty if decision-making capacity is absent and surrogates or health care agents are directing decisions.

Does dialysis or nondialysis medical therapy have value or create harm for a patient with advanced frailty? Does either enhance or diminish quality of life in these patients? These questions are complex questions that involve assessment of both physical and psychological levels framed by the patient’s personal narrative, cultural and religious background, support system, and exploration of what value and quality of life mean for that individual patient. Renal replacement therapy will address uremic syndrome and fluid overload-related issues, and it generally but not always (47) extends survival. In addition, the dialysis trajectory is associated with potential complications that should be disclosed and discussed, including (34) sudden death, which may occur while on the dialysis machine, cardiovascular events, recurrent and prolonged hospitalizations, infections like catheter-related bacteremia, need for long-term care after hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions (4), chronic critical illness (48), increasing frailty, functional decline, loss of independence, and dialysis discontinuation with an average survival of 8–10 days (7,49,50). There is no evidence that dialysis can reverse geriatric syndromes like frailty, functional disability, and dementia.

Additional concerns relate to symptom and quality of life measures. Both advanced CKD and dialysis patients can experience a significant symptom burden that may persist with renal replacement therapy (13,51). This burden may be, in part, because of inadequate symptom assessment and treatment and underuse of palliative medicine expertise (13). Although quality of life is ultimately a personal value judgment, many health-related quality of life indicators do not appear to improve over the course of dialysis (52). CKD patients exhibit compromised health-related quality of life that worsens as GFR decreases and is correlated with increasing age, decreasing serum albumin, and increasing comorbidities (53). One study revealed similar impairments in both advanced CKD and maintenance dialysis patients groups with regard to symptom load, quality of life, and depression (54). Alternatively, nondialysis therapy may be associated with a stable functional status until late in the trajectory, fewer hospitalizations, and more deaths at home (55,56).

A range of issues and attitudes regarding dialysis choices has been studied (43,57–60), and they reflect the ethical challenges that providers and patients face. In a series of open-ended interviews and participant observation (43) involving 43 dialysis patients and their choices, only two patients were described as proactive. Descriptors of patient experiences included there was “no decision—it just happens,” “I had no choice,” “I wanted to live,” and “when you will need to start dialysis” and not if. This finding suggests that primary emphasis is on mortality (survival and life expectancy) rather than the increasing geriatric, comorbid, and quality of life issues related to the dialysis trajectory. Sharing more information about this latter aspect is needed when considering quality of life preferences, because the course in frail patients is one of decline, regardless of whether dialysis or nondialysis therapy is chosen.

Frail advanced CKD patients require increasing support and palliative care with ongoing reassessment and heightened communication. The need for better communication was illustrated in a small study looking at kidney disease trajectory discussions between nephrologists and their older advanced CKD and dialysis patients (60). Patient-based themes included uncertainty about the disease trajectory and lack of preparation for living with dialysis, whereas nephrologist-related issues included difficulty explaining illness complexity, difficulty managing a disease over which they have little control, and the tendency to avoid discussions about the future. These findings suggest barriers to optimal patient choices by limiting the ability to weigh benefits, burdens, and best interests concerns. This information may have relevance to another study, where 62% of patients regretted their decision to start dialysis; the majority chose dialysis over supportive care, because it was their physician’s choice (52%) or family’s wishes (15%) (61).

Interventions to guide patients facing ESRD treatment choices include shared decision-making and decision aids (59). As part of the “Choosing Wisely” campaign to help health care providers optimize the medical decision-making process and empower patients, the 2012 American Society of Nephrology Quality and Patient Safety Task Force recommends to “not initiate chronic dialysis without ensuring a shared decision-making process between patients, their families, and their physician” (62). Individual patient goals and preferences underlie this shared decision-making process, and therefore, information on prognosis and expected benefits and harms of dialysis must be analyzed within the context of these goals and preferences. Focusing on outcomes with empathetic statements and questions that elicit big picture goals (34) first and then integrating them into a realistic ESRD treatment plan is required to make an informed decision. This information is the domain of ACP (63), which improves the chances of implementing patient wishes and increases both patient and family satisfaction at EOL (64,65).

Also of interest is the increasing use of decision aids that provide information on options in complex medical decisions and help patients clarify and communicate the personal values that they associate with different features of the options; however, these aids do not advise people to choose one over another option (66). These decision tools improve patient knowledge, risk perception, and realistic expectations of treatment options, help incorporate patient values in decision-making, and reduce decisional conflict (59,67–69). Two CKD-specific patient decision aids (what type of dialysis should I have? and should I stop kidney dialysis?) are available (70). Although studies need to be done to evaluate these kinds of tools, the development of CKD-specific decision support best practices for renal patients along the CKD trajectory (59) will improve the quality of choices for the frail renal phenotype.

Conclusion

Renal physicians can no longer consider dialysis de facto treatment for all ESRD patients. The realities and achievable end points of dialysis therapy for frail renal patients must be linked to their goals moving beyond not only living quantitatively but also exploration into what life means on a daily basis. Patients and their physicians must determine what quality of life is desirable and attainable, how it is to be achieved, and what risks and disadvantages are associated with the desired quality target (41).

Taken together, in evaluating a patient with advanced frailty for dialysis, the nephrologist should

review ethical principles, the process of shared decision-making, and fundamental goals of medicine;

discuss frailty as a biologic syndrome with vulnerability to adverse outcomes;

use the frail renal phenotype to supplement other prognostic information about what life with dialysis constitutes for an elderly frail patient;

describe nondialysis medical therapy as an active multidisciplinary treatment option (71); and

explore big picture goals and match those goals with an appropriate and realistic ESRD treatment plan.

Fortunately, palliative or supportive renal care, with its emphasis on decision-making, the ACP process, and matching medical therapy to patient goals, is becoming a part of the management of renal patients (2,34,63,72,73). Its usage in CKD patients with advanced frailty will lead to more realistic discussions about likely outcomes with and without dialysis, resulting in better informed patient choices that will optimize quality of life and entail less suffering.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Kaufman SR, Shim JK, Russ AJ: Revisiting the biomedicalization of aging: Clinical trends and ethical challenges. Gerontologist 44: 731–738, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renal Physicians Association: Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman SR: Making longevity in an aging society: Linking ethical sensibility and Medicare spending. Med Anthropol 28: 317–325, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM: Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 146: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Renal Data System (USRDS): Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2008, p 113 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG: Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2960–2967, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shlipak MG, Stehman-Breen C, Fried LF, Song X, Siscovick D, Fried LP, Psaty BM, Newman AB: The presence of frailty in elderly persons with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 861–867, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roshanravan B, Khatri M, Robinson-Cohen C, Levin G, Patel KV, de Boer IH, Seliger S, Ruzinski J, Himmelfarb J, Kestenbaum B: A prospective study of frailty in nephrology-referred patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 912–921, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, Bacchetti P, Garg AX, Kaufman JS, Walter LC, Mehta KM, Steinman MA, Allon M, McClellan WM, Landefeld CS: Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2758–2765, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao Y, Dalrymple L, Chertow GM, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL: Frailty, dialysis initiation, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 172: 1071–1077, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, Rotondi AJ, Cohen LM, Zeidel ML, Arnold RM: Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1345–1352, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko FC: The clinical care of frail, older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 27: 89–100, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss AH: Revised dialysis clinical practice guideline promotes more informed decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2380–2383, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1256–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group: Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: M146–M156, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, Tracy RP, Kop WJ, Hirsch CH, Gottdiener J, Fried LP; Cardiovascular Health Study: Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 162: 2333–2341, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leng S, Chaves P, Koenig K, Walston J: Serum interleukin-6 and hemoglobin as physiological correlates in the geriatric syndrome of frailty: A pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc 50: 1268–1271, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walston J, Fedarko N, Yang H, Leng S, Beamer B, Espinoza S, Lipton A, Zheng H, Becker K: The physical and biological characterization of a frail mouse model. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63: 391–398, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko F, Yu Q, Xue QL, Yao W, Brayton C, Yang H, Fedarko N, Walston J: Inflammation and mortality in a frail mouse model. Age (Dordr) 34: 705–715, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Himmelfarb J, Stenvinkel P, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM: The elephant in uremia: Oxidant stress as a unifying concept of cardiovascular disease in uremia. Kidney Int 62: 1524–1538, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stenvinkel P: Interactions between inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. J Ren Nutr 13: 144–148, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fried LP, Hadley EC, Walston JD, Newman AB, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, Harris TB, Ershler WB, Ferrucci L: From bedside to bench: Research agenda for frailty. Sci SAGE KE 2005: pe24, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Renal Data System (USRDS): Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2004, p 128 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Painter P, Kuskowski M: A closer look at frailty in ESRD: Getting the measure right. Hemodial Int 17: 41–49, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, Morton SC, Hughes RG, Hilton LK, Maglione M, Rhodes SL, Rolon C, Sun VC, Shekelle PG: Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 148: 147–159, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swidler MA: Palliative Care and Geriatric Treatment of Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. NephSAP Geriatric Nephrology, Washington, DC, American Society of Nephrology, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martocchia A, Frugoni P, Indiano I, Tafaro L, Comite F, Amici A, Cacciafesta M, Marigliano V, Falaschi P: Screening of frailty in elderly patients with disability by the means of Marigliano-Cacciafesta polypathology scale (MCPS) and Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) scales. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 56: 339–342, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniels R, van Rossum E, de Witte L, Kempen GI, van den Heuvel W: Interventions to prevent disability in frail community-dwelling elderly: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 8: 278, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Li M: Geriatric hemodialysis rehabilitation care. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 15: 115–122, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M: Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 361: 1612–1613, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura MK, Tan JC, O'Hare AM: Optimizing renal replacement therapy in older adults: A framework for making individualized decisions. Kidney Int 82: 261–269, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swidler MA: Geriatric renal palliative care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67: 1400–1409, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HD Mortality Predictor. Available at: http://touchcalc.com/calculators/sq Accessed November 29, 2012

- 36.Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, Seddon P, Zeidel ML: A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med 108: 609–613, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Couchoud C, Labeeuw M, Moranne O, Allot V, Esnault V, Frimat L, Stengel B; French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (REIN) registry: A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1553–1561, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, Gansor J, Senft S, Weaner B, Dalton C, MacKay K, Pellegrino B, Anantharaman P, Schmidt R: Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1379–1384, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G: Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59: 255–263, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakowski DA, Caillard S, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC: Dementia as a predictor of mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1000–1005, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ: Clinical Ethics, New York, McGraw-Hill Medical, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lo B: Resolving Ethical Dilemmas: A Guide for Clinicians, Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman SR, Shim JK, Russ AJ: Old age, life extension, and the character of medical choice. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61: S175–S184, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fried TR, O’Leary J, Van Ness P, Fraenkel L: Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 1007–1014, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miura Y, Asai A, Matsushima M, Nagata S, Onishi M, Shimbo T, Hosoya T, Fukuhara S: Families’ and physicians’ predictions of dialysis patients’ preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 122–130, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D: The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med 166: 493–497, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, Carson SS: Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 446–454, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen LM, Germain M, Poppel DM, Woods A, Kjellstrand CM: Dialysis discontinuation and palliative care. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 140–144, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murtagh F, Cohen LM, Germain MJ: Dialysis discontinuation: Quo vadis? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 379–401, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall JM, Edmonds PM, Donohoe P, Carey I, Jenkins K, Higginson IJ: Symptoms in advanced renal disease: A cross-sectional survey of symptom prevalence in stage 5 chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis. J Palliat Med 10: 1266–1276, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gabbay E, Meyer KB, Griffith JL, Richardson MM, Miskulin DC: Temporal trends in health-related quality of life among hemodialysis patients in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 261–267, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mujais SK, Story K, Brouillette J, Takano T, Soroka S, Franek C, Mendelssohn D, Finkelstein FO: Health-related quality of life in CKD Patients: Correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1293–1301, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD: Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1057–1064, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murtagh FE, Sheerin NS, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ: Trajectories of illness in stage 5 chronic kidney disease: A longitudinal study of patient symptoms and concerns in the last year of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1580–1590, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A: Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1611–1619, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, Rose J, Masterson R, Johnson DW, Howard K: Factors influencing patient choice of dialysis versus conservative care to treat end-stage kidney disease. CMAJ 184: E277–E283, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC: The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 340: c112, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murray MA, Brunier G, Chung JO, Craig LA, Mills C, Thomas A, Stacey D: A systematic review of factors influencing decision-making in adults living with chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Couns 76: 149–158, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, Fink JC, Jaber BL, Linas SL, Michael B, O’Hare AM, Schaefer HM, Shaffer RN, Trachtman H, Weiner DE, Falk AR; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force: Critical and honest conversations: The evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1664–1672, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holley JL: Advance care planning in CKD/ESRD: An evolving process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1033–1038, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W: The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 340: c1345, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL: Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 946–950, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS). Available at: http://ipdas.ohri.ca/ Accessed November 26, 2012

- 67.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S: Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 366: 780–781, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Légaré F, Thomson R: Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10: CD001431, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murray MA, Thomas A, Wald R, Marticorena R, Donnelly S, Jeffs L: Exploring the impact of a decision support intervention on vascular access decisions in chronic hemodialysis patients: Study protocol. BMC Nephrol 12: 7, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa Health Research Institutes A to Z Inventory of Decision Aids. Available at: http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/index.html

- 71.Murtagh FE, Murphy E, Shepherd KA, Donohoe P, Edmonds PM: End-of-life care in end-stage renal disease: Renal and palliative care. Br J Nurs 15: 8–11, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davison SN: Integrating palliative care for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: Recent advances, remaining challenges. J Palliat Care 27: 53–61, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Swidler M: Geriatric renal palliative care is coming of age. Int Urol Nephrol 42: 851–855, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]