Abstract

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is an uncommon, slow growing malignant salivary gland tumor that is characterized by wide local infiltration, perineural spread, propensity to local recurrence and distant metastasis. In this paper, the authors present a case of adenoid cystic carcinoma affecting the palate and involving the maxillary sinus in a 60-year-old male patient along with a brief review of literature.

Keywords: Adenoid cystic carcinoma, malignant salivary gland tumor, maxillary sinus, palate

INTRODUCTION

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ADCC) is a malignant salivary gland tumor that was first described by Billroth in 1859[1] under the name cylindroma attributing to its cribriform appearance formed by the tumor cells with cylindrical pseudolumina or pseudospaces. The term “adenoid cystic carcinoma” was introduced by Ewing (Foote and Frazell) in 1954. ADCC is a relatively rare malignant salivary gland tumor comprising less than 1% of all malignancies of head and neck. It is the 5th most common malignancy of salivary gland origin, representing 5-10% of all salivary gland neoplasms.[2,3]

The parotid and submandibular glands are the two most common sites for ADCC accounting for 55% of the cases. Among the major glands, the parotid is the most common site of occurrence.

Intraorally 50% of ADCCs occur on the palate. ADCC accounts for 8.3% of all palatal salivary gland tumors and 17.7% of malignant palatal salivary gland tumors (AFIP series). The other less common sites are lower lip, retromolar tonsillar pillar area, sublingual gland, buccal mucosa and floor of the mouth.[3] The nose and paranasal sinuses represent the next most common sites for minor gland ADCCs.[4]

The tumor is most often clinically deceptive by its small size and slow growth, which actually overlies its extensive subclinical invasion and marked ability for early metastasis making the prognosis questionable.[5] The three recognized histological variants of ADCC are cribriform, tubular and solid although, cribriform is the most commonest and solid is the least commonest. It is recognized that most ADCCs do not occur in “pure” cribriform, tubular or solid types. It is not uncommon to have more than one histopathologic pattern in a single neoplasm and rather all three patterns can be observed in the majority of tumors. Generally tumors are classified according to the histologic pattern that predominates. The main reason for histological typing is to assess the prognostic difference between histologic types. Tubular pattern (well differentiated) is believed to have the best prognosis compared to the cribriform pattern (moderately differentiated) and solid pattern (poorly differentiated).[6] ADCC is graded according to Szanto, et al. as cribriform or tubular (grade I), less than 30% solid (grade II) or greater than 30% solid (grade III).[7]

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a chief complaint of pain and discharge in the upper left back region of the jaw since one and half years. According to the patient one year prior to our consultation, he got the maxillary molars extracted from a local dentist due to pain and mobility of the teeth in that area. Upon consultation patient revealed that the pain continued to exist even after the extraction.

The extra oral examination was within normal limits with no evidence of lymphadenopathy. The patient is a known hypertensive and is on medication since three years for the same. The patient had smoking habit, which he quit only a couple of years ago. Intraoral examination revealed a solitary erythematous swelling with diffuse borders involving the left posterior portion of hard palate and was also seen involving the soft palate on the same side. The swelling was seen extending from mesial aspect of first premolar to 1 cm posterior to tuberosity on left side, involving the palatal area but not crossing the midline [Figure 1]. An oro-antral communication was seen with purulent discharge. The remainder of the intraoral examination was within normal limits.

Figure 1.

Intraorally, the lesion was seen involving the hard and soft palate but not crossing the midline

The swelling was nontender. The inspectory findings were confirmed on palpation. CT scan revealed complete obliteration of the left maxillary sinus [Figure 2]. The clinical differential diagnosis included a benign or malignant neoplasm of minor salivary glands, a neoplasm of maxillary sinus.

Figure 2.

CT scan showing complete obliteration of left maxillary sinus

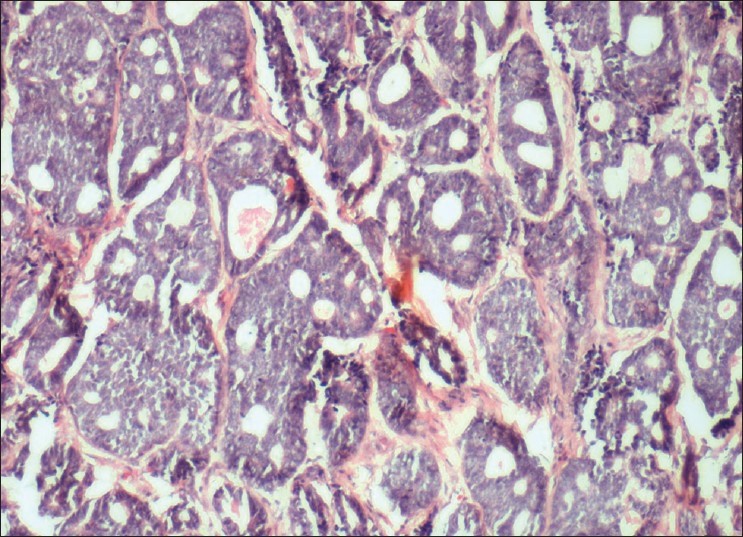

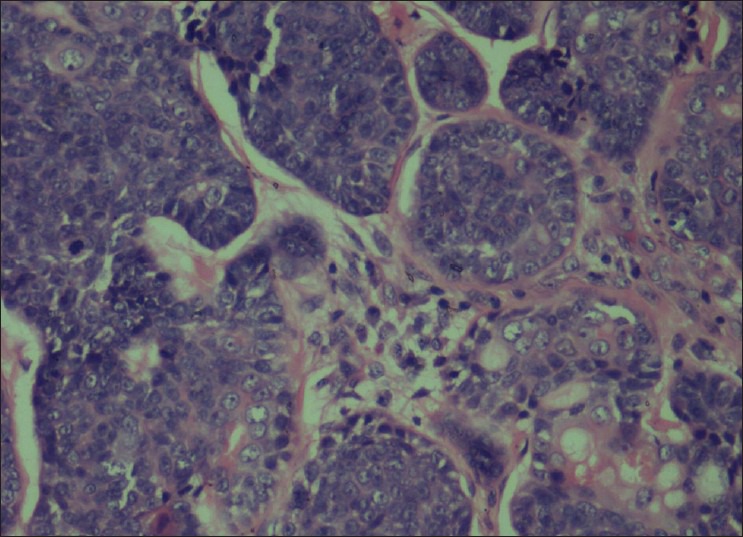

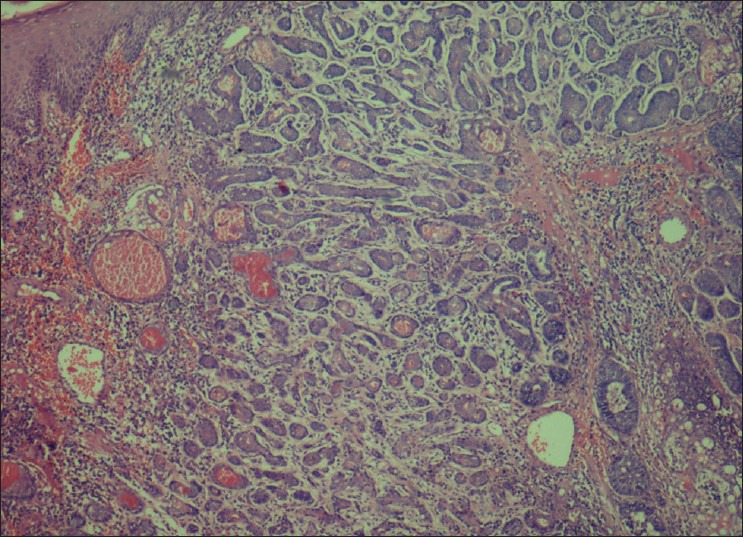

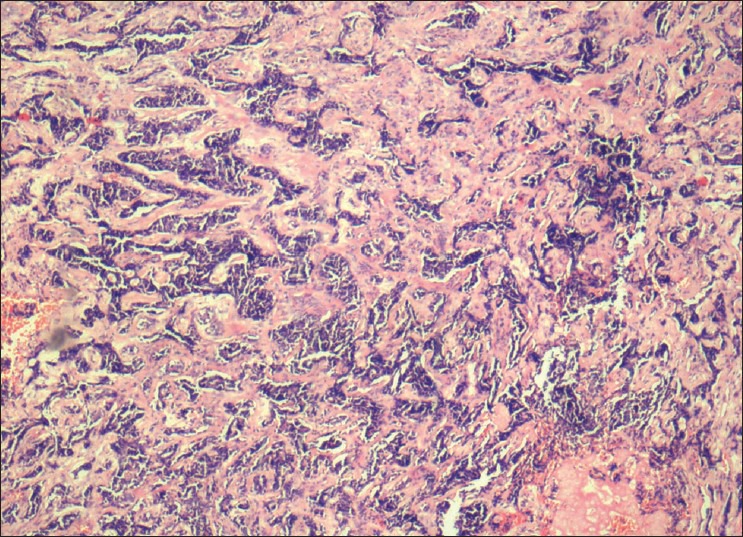

An incisional biopsy of palate and sinus lining was performed. Histopathological examination revealed fibrous stroma with areas of hyalinization. Islands of uniform cells arranged in cord-like pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei were seen enclosing round to oval pseudocystic spaces in the stroma. Few of these spaces showed eosinophilic coagulum [Figure 3]. The tumor cells are also seen arranged in the form of solid islands [Figure 4] and ductal pattern [Figure 5]. The present case showed all the three histological types. There was no evidence of perineural invasion even on serial sectioning. Focal areas showed small cords and longitudinal tubules of isomorphic cells set in a background of densely hyalinized stroma [Figure 6].

Figure 3.

Variable-sized cribriform spaces formed by small deeply basophilic cells imparting Swiss cheese pattern

Figure 4.

Solid pattern composed of nests of basaloid cells and mitotic figures

Figure 5.

Tubular pattern characterized by ductal structures formed by layers of isomorphic basaloid cells

Figure 6.

Tubules of isomorphic tumor cells set in a densely hyalinized stroma

A diagnosis of ADCC (cribriform pattern) was established. The patient was treated by wide surgical excision with clear margins and hemi-maxillectomy of left maxillary region with post-radiotherapy. The present case was staged as T4N0M0 based on American Joint Committee on cancer as a guide to prognosis. The patient was under regular follow-up and is free of the disease at one-year follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Adenoid cystic carcinoma most often presents a diagnostic and treatment challenge owing to the rarity of the lesion. Most findings regarding ADCC are actually based upon studies with a small number of patients and there is a need for further information regarding its clinical behaviour as well as treatment modalities and their results.[8]

ADCC may occur at any age although in most cases the patients’ age ranged from 24 to 78 years. The age of patients affected with major salivary gland tumors has been shown to be younger (mean 44 years) compared to the age of those who developed tumors of the minor glands (mean 54 years) and shows female predilection (F:M − 1.2:1). Pain is a common and important finding, occurring early in the course of the disease before there is a noticeable swelling.[9] Neoplastic cell neurotropism causes pain.

Among the minor salivary glands, palate is more commonly involved generally the area of greater palatine foramen.

Among the malignant neoplasms of minor salivary glands, the most common was mucoepidermoid carcinoma (21.8%) followed by polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) (7.1%) and ADCC was the third most common (6.3%).[10,11]

ADCCs of the minor glands have been reported to have worse prognosis than those of the major salivary glands.[12,13] Tumors involving the nose, paranasal sinuses and maxillary sinus have the worst prognosis as they are usually detected with higher stages at the time of diagnosis.[14] Tumors of minor salivary glands usually have the tendency to infiltrate extra glandular soft tissues and bone thereby allowing increased dissemination of the tumor. Lymph node involvement is uncommon (< 5% of cases) and is usually due to contiguous spread rather than lymphatic permeation or embolization.[15]

The differential diagnosis of ADCC includes PLGA, basal cell adenoma (BCA), mixed tumor and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (BSC). The cribriform pattern so typical of ADCC may also rarely be seen in BCA, mixed tumor and PLGA, and the distinction between PLGA and ADCC is more challenging. A polymorphous architecture characterizes PLGA whereas ADCC has a more limited range of histologic patterns with no more than three patterns. Foci of papillary growth and areas of single cell infiltration are characteristic of PLGA. Basophilic pools of glycosaminoglycans are seen in ADCC but not in PLGA. PLGA shows uniform cell population with cytologically bland, round or oval vesicular nuclei and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm where as cells in ADCC have clear cytoplasm, angular, hyperchromatic nuclei and may show mitotic activity. The Ki-67 index is reported to be 10 times higher in ADCC compared to PLGA. Smooth muscle markers of myoepithelial differentiation are positive in ADCC but negative in PLGA.[16] Though PLGA may form solid areas, they lack the overall high-grade feel associated with ADCC.

Occasional foci in pleomorphic adenoma (PA) can resemble ADCC but the presence of typical myxochondroid matrix and plasmacytoid or spindle shaped cells helps to avoid confusion.[17]

Cribriform structures may sometimes be observed in BCA and such cases can be differentiated from ADCC on the basis of gradual structural alteration from areas typical of BCA. The peripheral palisading and focal squamous differentiation with whorling pattern present in BCA are not usually encountered in ADCC.[18]

BSC should be differentiated from solid ADCC of minor salivary glands. The basement membrane material secreted by BSC tends to dissect between tumor cells rather than form crisp cribriform spaces seen in ADCC. Focal keratinization, attachment to rete pegs, and presence of surface squamous dysplasia or carcinoma in situ helps to distinguish it from ADCC. Furthermore p63 staining is diffuse in BSC compared to ADCC.[19]

Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the pseudocysts are positive for periodic acid schiff reagent (PAS) and Alcian blue and contain basement membrane components such as type IV collagen, heparin sulfate and laminin isoforms. Epithelial cells are positive for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Duct lining cells are positive for C-kit (CD117) and myoepithelial cells are positive for S-100 protein, calponin, p63, smooth muscle actin and myosin. Expression of S-100, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neural cell adhesion molecule have been correlated with the presence of perineural invasion. P53 mutations appear to be involved with tumor progression and recurrence.[20]

Molecular genetic data: Alterations in chromosomes 6q, 9p and 17p12-13 are the most frequent cytogenetic alterations reported. One half of the cases show genomic deletions of chromosome 6. Candidate suppressor genes have also been mapped to chromosome 12. Hypermethylation of the promoter region of the p16 gene was associated with higher histologic grades of malignancy. Microarrays and comparative genomic hybridization have been used to identify candidate genes for ADCC.[20]

Possible treatment modalities available for the treatment of ADCC are surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and combined therapy. It requires excision with the widest surgical margins possible as tumor cells extend well beyond the clinical and radiographic margins. Neutron therapy, which involves larger particles of greater energy can achieve reasonable local control as a primary therapeutic modality. Adoptive immunotherapy along with chemoradiotherapy has recently shown promising results. E-cadherin expression can be used as prognostic marker. High argyrophilic nuclear organizing regions (AgNor) counts may be predictive of metastasis.[6] Main factors associated with patient survival are anatomic location, primary lesion size, presence or absence of metastasis at the time of diagnosis, perineural invasion and histological variant.[21]

Long-term survival is particularly low in grade III tumors. Distant metastasis occurs in 25%-50% of patients and lung is the most common involved site.[22] The present patient showed no pleural or parenchymal abnormalities on chest X-ray.

The 5-year survival rate after effective treatment is 75%, but long-term survival rates are low (10 years-20% and 15 years-10%).

The present patient was recalled at every 6-month interval in view of the sinus involvement and propensity for distant metastasis.

CONCLUSION

ADCC is rather an uncommon salivary gland malignancy. It is unique for its peculiar histopathological features and tendency for perineural invasion. Lesions involving the sinus tend to have a poor prognosis due to its infiltrative growth and distant metastasis. Long-term follow-up of patient at regular intervals is mandatory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors like to acknowledge the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, S.B.Patil Dental College and Hospital, Bidar, Karnataka, India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Lucas RB. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. Pathology of tumors of the oral tissues; pp. 330–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuba HM, Spector GJ, Thawley SE, Simpson JR, Mauney M, Pikul FJ. Adenoid cystic salivary gland carcinoma: A histomorphologic review of treatment failure patterns. Cancer. 1986;67:519–24. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860201)57:3<519::aid-cncr2820570319>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: Factors influencing survival. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;138:579–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HK, Sung MW, Chung PS, Rhee CS, Park CI, Kim WH. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:721–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880310027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx RE, Stern D. Chicago: Quintessence; 2002. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, A rational for diagnosis and management; pp. 550–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnepp DR, Henley JD, Roderick HW, Simpson, Eveson J. Salivary and lacrimal glands. In: Gnepp Douglas R., editor. Diagnostic surgical pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009. pp. 482–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szanto PA, Luna MA, Tortoledo ME, White RA. Histologic grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Cancer. 1984;54:1062–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840915)54:6<1062::aid-cncr2820540622>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grahne B, Lauren C, Holsti LR. Clinical and histological malignancy of adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1977;91:743–9. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100084310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neville BW, Damm D, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Salivary gland pathology. In: Neville, editor. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. Missouri: Saunders; 2009. pp. 495–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of intra oral minor salivary gland tumors: A study from northern California and comparison to reports from other parts of the world. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:207–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashemi Pour MS, Zarei MR, Chamani G, Rad M. Malignant salivary glands tumors in Kerman province: A Retrospective Study. Dent Res J. 2007;4:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nascimento AG, Amaral AL, Prado LA, Kligerman J, Silveira TR. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands: A study of 61 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Cancer. 1985;57:312–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860115)57:2<312::aid-cncr2820570220>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dal Maso MD, Lippi L. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: A clinical study of 37 cases. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:177–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokemueller H, Eckardt A, Brachvogel P, Hausamen JE. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: A 20 years experience. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:25–31. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen MS, Jr, Marsh WL., Jr Lymphnode involvement by direct extension in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Absence of classic embolic lymphnode metastasis. Cancer. 1976;38:2017–21. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197611)38:5<2017::aid-cncr2820380525>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad AR, Savera AT, Gown AM. The myoepithelial immunophenotype in 135 benign and malignant salivary gland tumors other than pleomorphic adenoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:801–6. doi: 10.5858/1999-123-0801-TMIIBA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogawa I, Miyauchi M, Matsuura H. Pleomorphic adenoma with extensive adenoid cystic carcinoma – like cribriform areas of parotid gland. Pathol Int. 2003;53:30–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagao K, Matsuzaki O, Saiga H, Sugano I, Shigematsu H, Kaneko T, et al. Histopathologic studies of basal cell adenoma of the parotid gland. Cancer. 1982;50:736–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820815)50:4<736::aid-cncr2820500419>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emanuel P, Wang B, Wu M. P63 immunohistochemistry in the distinction of adenoid cystic carcinoma from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:645–50. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John W, Toshitaka N. Diseases of the salivary glands. In: Barnes L, editor. Surgical pathology of the head and neck. 3rd ed. New York: Informa Health Care; 2009. pp. 552–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett A, Speight P. The controversial adenoid cystic carcinoma. The implications of histological grade and perineural invasion. In: Mc Gurk M, Renehan A, editors. Controversies in the management of salivary gland disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 211–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laura D. Lung metastasectomy in Adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary gland. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:890–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]