Abstract

Purpose

To test the hypothesis that consolidation therapy with yttrium-90 (90Y) –ibritumomab tiuxetan after brief initial therapy with four cycles of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in patients with previously untreated mantle-cell lymphoma would be a well-tolerated regimen that would improve outcomes compared with historical R-CHOP data.

Patients and Methods

Patients ≥ 18 years old with histologically confirmed mantle-cell lymphoma expressing CD20 and cyclin D1 who had not received any previous therapy and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2 and adequate organ function were eligible. The study enrolled and treated 57 patients, of whom 56 patients were eligible. Fifty-two patients (50 eligible patients) received 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan. The study design required 52 eligible patients to detect a 50% improvement in the median time to treatment failure (TTF) compared with that reported for six cycles of R-CHOP.

Results

With 56 analyzed patients (median age, 60 years; men, 73%), the overall response rate was 82% (55% complete response/complete response–unconfirmed). With a median follow-up of 72 months, the median TTF was 34.2 months. The median overall survival (OS) has not been reached, with an estimated 5-year OS of 73% (79% for patients ≤ age 65 years v 62% for patients > age 65 years; P = .08 [log-rank test]). There were no unexpected toxicities.

Conclusion

R-CHOP given for four cycles followed by 90Y–ibritumomab tiuxetan compared favorably with historical results with six cycles of R-CHOP in patients with previously untreated mantle-cell lymphoma. This regimen was well tolerated and should be applicable to most patients with this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Mantle-cell lymphoma (MCL) has distinct genetic alterations, biologic features, and clinical behavior.1 The t(11;14) cytogenetic translocation leads to dysregulated cyclin D1 expression.2 Confirming the diagnosis of MCL requires demonstrating t(11;14), usually by fluorescent in situ hybridization, or the expression of cyclin D1 by immunohistochemistry. The MCL immunophenotype is characterized by monoclonal B cells expressing CD19, CD20, and CD5 but lacking coexpression of CD23. Clinically, MCL at diagnosis has a median age in the seventh decade with predominance in men and is usually advanced stage with a propensity to involve bone marrow, spleen, and extranodal sites. MCL is incurable with standard chemotherapy, like other indolent lymphomas, but has a shorter median survival.

A benchmark for comparison of treatment outcomes in lymphoma, including MCL, is rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). R-CHOP as initial therapy for untreated MCL yields a high response rate, but remissions are not durable.3,4 Although induction therapy with rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone, alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate-cytarabine, has better reported results,5,6 results in patients older than age 65 years are not as promising and this regimen is difficult to administer in larger group settings.7,8

Another approach to improve R-CHOP outcomes is to add consolidation therapy, such as high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell support (HDC/ASCT).9 HDC/ASCT, however, is not applicable to all patients and, although it prolongs progression-free survival (PFS), is not curative. More intensive induction, including high-dose cytarabine, followed by HDC/ASCT consolidation has yielded promising results,10–12 although the median age in these trials was 56 to 58 years.

Because MCL is predominantly a disease of patients older than age 60 years, and R-CHOP achieves high response rates of relatively short duration, we sought to test a consolidation strategy that would be applicable to most patients with MCL. Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) is active in heavily pretreated patients with MCL.13 RIT as initial therapy has a high response rate but disappointing duration.14 The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) tested the hypothesis that RIT consolidation by using yttrium-90 (90Y) –ibritumomab tiuxetan after brief initial therapy with four cycles of R-CHOP would be a well-tolerated and effective regimen for patients with previously untreated MCL.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

From protocol activation in November 2003 to closure in February 2005, 57 patients were enrolled from 16 United States centers. Patients were eligible if they had histologically confirmed CD20-positive mantle-cell lymphoma expressing cyclin D1 and/or having t(11;14), had received no previous therapy (< a 2-week course of glucocorticoids was permitted), and had at least one site of measurable disease. Patients had to be ≥ 18 years old with no upper limit. Other inclusion criteria were as follows: ECOG performance status of 0 to 2; neutrophils greater than 2,500/μL and platelets greater than 100,000/μL unless as a result of disease involving the bone marrow; total bilirubin less than 1.5 mg/dL (1.5 to 3.0 mg/dL was allowed if as a result of liver involvement by lymphoma); serum creatinine less than 2.0 mg/dL, AST and ALT less than 2.5× the institutional upper normal limit, and calcium less than 11.5 mg/dL. Patients had no previous history of malignancy, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer, carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix, or a surgically cured malignancy and disease free ≥ 3 years. Patients were ineligible it they had known CNS lymphoma, HIV infection, or comorbidities precluding R-CHOP therapy. The left ventricular ejection fraction needed to be greater than 45%, and patients had to have an expected life span more than 6 months. Each site was required to obtain and maintain ongoing approval from its local human investigations committee. Investigators obtained informed consent from each participant. The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov.

Patients who completed four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy without disease progression proceeded to RIT with the 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan regimen if they had bone marrow less than 25% involved by lymphoma and ≥15% cellular, an absolute neutrophil count greater than 1,500/μL, platelets greater than 100,000/μL, serum creatinine less than 2.0 mg/dL, total bilirubin less than 2.0 mg/dL and AST and ALT less than 2.5× the institutional upper normal limit.

Pathology and Flow Cytometry

A central pathology review was performed for 49 of 57 cases (86%), with a confirmed diagnosis of MCL in 44 of 49 cases. Of the five cases that were centrally reviewed but did not have confirmed MCL, one case was considered mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. The other four cases appeared likely to be MCL on the basis of a morphologic review and reported immunophenotypic data. Of the eight cases that were not centrally reviewed, all appeared likely to be MCL on the basis of a review of pathology reports and immunophenotypic data. Therefore, 56 of 57 patients were considered to have the correct histology and were included in the final analysis. Baseline blood samples were to be sent to the Leukemia Translational Studies Laboratory of the ECOG for flow cytometric immunophenotyping.15 Samples were analyzed for 43 patients, of whom 38 patients (88%) had detectable clonal B cells.

Treatment Plan

R-CHOP was administered on day one and repeated every 3 weeks for four cycles. Rituximab 375 mg/m2 was infused intravenously (IV) by using institutional standard escalating rates after acetaminophen and diphenhydramine premedication. Prednisone was given at a 100-mg total dose orally per day for 5 days, with the first dose given before receiving rituximab. Antiemetics were given at the discretion of the treating physician. This treatment was followed by cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2 IV, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 IV, and vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 IV (maximum dose, 2 mg). Standard dose reductions were used for hematologic, hepatic, and neurologic toxicity. Myeloid growth factors were not mandated but could be used at the discretion of the physician. Stem-cell collection for storage was neither mandated nor prohibited but, if collected, was performed by using myeloid growth factor during recovery from cycle four of R-CHOP and not with additional chemotherapy.

The standard 90Y-RIT treatment program, consisting of 5 mCi 111In– ibritumomab tiuxetan tracer dose given after rituximab 250 mg/m2 on day 1, subsequent imaging to ensure adequate biodistribution, and 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan given after rituximab 250 mg/m2 on day 8, was to begin within 4 to 8 weeks from the last administration of R-CHOP. Bone marrow was examined in that interval to ensure adequate cellularity and less than 25% marrow involvement by lymphoma. The dose of 90Y, which was capped at 32 mCi, was 0.4 mCi/kg if the platelet count was ≥ 150,000/μL and was reduced to 0.3 mCi/kg if the platelet count was between 100,000/μL and 149,000/μL.

Evaluation of Toxicity and Response

All baseline imaging and laboratory studies were performed less than 4 weeks before the start of treatment. A complete physical examination was performed at the start of treatment, before each treatment cycle, 3 to 4 weeks after cycle four of R-CHOP, and at weeks 4, 8, and 12 after RIT. Computed tomography restaging for response evaluation was performed after cycles two and four of R-CHOP and 12 weeks after RIT. Positron emission tomography scans were not mandated. Subsequent monitoring per protocol included a physical examination and laboratory studies every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months through year 5, and then annually with computed tomography scans every 6 months for 5 years.

Responses were assessed per the Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Response Criteria International Workshop.16 Toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0.

Statistical Methods

The primary end point of the study was time to treatment failure (TTF), which was defined as the time from study entry to the first occurrence of progression, relapse after response, or death as a result of any cause. Howard et al3 reported a median TTF of 16 months for R-CHOP, which corresponds to a 1.5-year TTF of 44%. Study E1499 was designed to consider this treatment promising if the 1.5-year TTF was ≥ 60%, corresponding to a 50% increase in the median TTF compared with R-CHOP for six cycles. This design required 52 eligible patients, and allowing for 10% ineligibility and pathology exclusion, the total accrual goal was 57 patients. Among the 52 eligible patients, if ≥ 28 patients (54%) were free of treatment failure at 1.5 years, the treatment would be considered worth additional evaluation. The design provided 85% power and 10% type I error (one-sided).

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from registration to death as a result of any cause. OS and TTF were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparison between curves was analyzed by using log-rank tests. Fisher's exact tests were used to compare response rates between different patient groups.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

Fifty-seven patients were enrolled between March 2004 and February 2005. One patient was considered ineligible as a result of incorrect histology on central pathology review and was excluded from the analysis. Of the 56 analyzed patients (Table 1), 73% of patients were men, and the median age was 60 years (range, 33 to 83 years). An advanced stage of III to IV was present in 91% of patients, whereas 48% of patients had involvement of more than one extranodal site, and 82% of patients had bone marrow involvement. Performance status was 0 to 1 in all but one patient, B symptoms were present in 14 patients (25%), and seven patients (13%) had a mass ≥ 10 cm. The International Prognostic Index17 (IPI) was 0 to 2 in 52% of patients and 3 to 5 in 46% of patients (one patient was not evaluable for IPI and mantle-cell lymphoma IPI (MIPI) as a result of missing LDH). According to the mantle-cell lymphoma IPI,18 MIPI was low in 50% of patients, intermediate in 27% of patients, and high in 21% of patients.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographic or Characteristic | No. of Patients (N = 56) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 60 | |

| Range | 33-83 | |

| Sex, M | 41 | 73 |

| Stage | ||

| II | 5 | 9 |

| III | 3 | 5 |

| IV | 48 | 86 |

| PS | ||

| 0 | 32 | 57 |

| 1 | 23 | 41 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Marrow involved | 46 | 82 |

| B symptoms | 14 | 25 |

| Maximum nodal mass > 10 cm | 7 | 13 |

| IPI | ||

| Low, 0-1 | 16 | 29 |

| Low-intermediate, 2 | 13 | 23 |

| High-intermediate, 3 | 22 | 39 |

| High, 4-5 | 4 | 7 |

| MIPI | ||

| Low | 28 | 50 |

| Intermediate | 15 | 27 |

| High | 12 | 21 |

Abbreviations: IPI, International Prognostic Index; M, male; MIPI, mantle-cell lymphoma IPI; PS, performance status.

Outcome

Therapy was well tolerated, and 51 (91%) of the 56 analyzed patients received all planned treatment. Of the five patients who did not receive 90Y-RIT, three patients had disease progression, one patient died of myocardial infarction before the scheduled RIT, and one patient chose to receive another therapy. In no patients did the degree of marrow involvement or thrombocytopenia preclude RIT administration, which was at the full dose (0.4 mCi/kg) in 48 patients and at a 25% dose reduction as a result of lower platelets in three patients. One patient who received RIT was considered ineligible per the protocol because the patient had an absolute neutrophil count ≤ 1,500/μL when registered for RIT. This patient, who was included in the outcome analysis for R-CHOP but not for RIT, had no untoward toxicity from the RIT.

For the 56 eligible patients (Table 2), the overall response rate at completion of all therapy was 82%, with 50% complete responses (CRs), 5% complete response–unconfirmed (CRu), and 27% partial responses (PRs), assessed without functional imaging. After R-CHOP, there were eight CRs, 3 CRu (20%), and 28 PRs (50%), with 15 patients (27%) with stable disease. The response improved in 22 patients after 90Y-RIT treatment. Sixteen patients converted from PR to CR/CRu, three patients converted from stable disease to CR/CRu, and three patients converted from stable disease to PR. An additional six patients with PR after R-CHOP had additional improvement in their tumor measurements but remained classified as PRs. Response rates did not differ by age, which were (86%) (30 of 35) for patients ≤ 65 years old compared with 76% (16 of 21) for patients older than age 65 years, although there was a trend for patients older than age 65 years to have a lower rate of CR/CRu (48% v 60%, respectively).

Table 2.

Outcomes

| Category | No. of Patients | Response Rate | % | CR/CRu | % | Median TTF (months) | Median OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP* | 56 | 39 | 70 | 11 | 20 | 34.2 | NR |

| RIT† | 50 | 32 | 64 | 23 | 46 | 30.8 | NR |

| Age, years | |||||||

| ≤ 65 | 35 | 30 | 86 | 21 | 60 | 35.3 | NR |

| > 65 | 21 | 16 | 76 | 10 | 48 | 24.6 | 68.5 |

| P | .48 | .41 | .33 | .08 | |||

| IPI | |||||||

| 0-2 | 29 | 25 | 86 | 20 | 69 | 31.5 | NR |

| 3-5 | 26 | 20 | 77 | 10 | 38 | 34.6 | NR |

| P | .49 | .03 | .74 | .87 | |||

| MIPI baseline | |||||||

| Low | 28 | 28 | 100 | 17 | 61 | 36.4 | NR |

| Intermediate | 15 | 11 | 73 | 8 | 53 | 24.6 | NR |

| High | 12 | 6 | 50 | 5 | 42 | 10.2 | 65.6 |

| P | < .001 | .53 | .12 | .01 | |||

| Circulating lymphoma cells/μL | |||||||

| ≤ 5,000 | 49 | 41 | 84 | 28 | 57 | 34.5 | NR |

| > 5,000 | 7 | 5 | 71 | 3 | 43 | 12.6 | NR |

| P | .60 | .69 | .34 | .58 | |||

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CRu, complete response–unconfirmed; IPI, International Prognostic Index; MIPI, mantle-cell lymphoma IPI; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PS, performance status; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; RIT, radioimmunotherapy; TTF, time to treatment failure.

Response rate and CR/CRu were evaluated after fourth-cycle R-CHOP compared with baseline measurements. TTF and OS were calculated from study registration.

Response rate and CR/CRu were evaluated 3 months after RIT and compared with pre-RIT measurements. TTF and OS were calculated from RIT start.

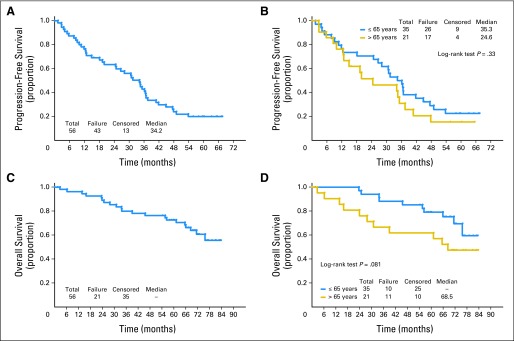

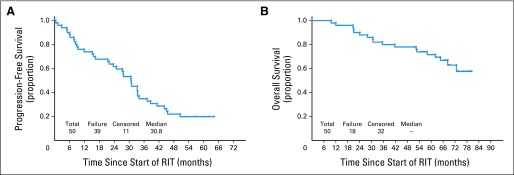

With a median follow-up of 72 months (Fig 1), the median TTF was 34.2 months. The estimated 1.5-year TTF was 69% (90% CI, 58% to 78%). For patients ≤ 65 years old versus patients older than age 65 years, the median TTF was 35.3 months versus 24.6 months, respectively (P = .33). The median OS has not been reached, with an estimated 3-year OS of 80% (90% CI, 69% to 87%; 88% for patients ≤ age 65 years v 67% for patients > age 65 years) and a 5-year OS of 73% (90% CI, 61% to 81%; 79% for patients ≤ age 65 years v 62% for patients > age 65 years; P = .08 [log-rank test]). The median TTF was 10, 25, and 36 months for high-, intermediate-, and low-risk MIPI, respectively, although statistical significance was not achieved (P = .12). Among the 50 eligible patients who received RIT (Fig 2), the median TTF from the start of RIT was 30.8 months, and the median OS has not been reached. The median TTF for patients with leukemic presentation was 11.9 months for the five patients with lymphocyte counts greater than 15,000/μL and 12.6 months for seven patients with lymphocyte counts greater than the cutoff of 5,000/μL. Although TTF for leukemic patients was shorter than the 34.5-month TTF for patients without leukemic presentation, this did not translate into a survival difference.

Fig 1.

For the 56 eligible patients enrolled onto the trial, (A) time to treatment failure and (C) overall survival are shown. For these 56 patients, (B) time to treatment failure and (D) overall survival by patients ≤ 65 years old versus patients older than age 65 years at enrollment onto the trial are shown.

Fig 2.

(A) Time to treatment failure and (B) overall survival for the 50 eligible patients who received radioimmunotherapy (RIT).

Of 43 events, 42 event were disease progression, whereas one event was from myocardial infarction before RIT. Of the other 20 deaths, 14 deaths were from MCL, and six deaths were from unknown or other causes.

Toxicity

There were no unexpected toxicities (Table 3). During R-CHOP administration, grade 3 or 4 toxicity included leukocytes (seven grade 3 and 20 grade 4 neutropenia), platelets (one grade 3 and two grade 4), neutropenic fever or infection (three grade 3 and one grade 4), anemia (one grade 3), diarrhea (two grade 3), metabolic abnormalities (10 grade 3), hyperuricemia (one grade 4), sensory neuropathy (two grade 3), syncope (one grade 3), oral mucositis (one grade 3), and dyspnea or hypoxia (three grade 3). After RIT, grade 3 or 4 toxicities were limited to leukocytes and platelets, except for a single episode of grade 3 hyperglycemia. Neutropenia occurred in 39 of 52 patients (17 grade 3 and 11 grade 4). Thrombocytopenia was reported in 49 patients (eight grade 3 and 16 grade 4). There was no grade 3 or 4 anemia (37 grade 1 or 2), and no patient developed neutropenic fever. Overall, there were 46 patients with a grade 2 or greater reduction in neutrophils, hemoglobin, or platelets after RIT. Of these patients, 38 patients (83%) recovered to grade 1 or better by week 12 after RIT, five patients by recovered to grade 1 or better by week 16, and only two patients still had low counts at week 16 (one patient with grade 3 neutropenia and one patient with grade 2 thrombocytopenia). One patient developed myelodysplasia 6 years after RIT with intervening diagnoses of pancreatic neuroendocrine and metastatic renal cell cancers as well as additional therapy for recurrent MCL.

Table 3.

Grade 3 or 4 Toxicities During Chemotherapy and RIT

| Toxicity | R-CHOP |

RIT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Hemoglobin | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Leukocytes | 8 | 14 | 10 | 18 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Lymphopenia | 11 | 19 | 6 | 11 | 18 | 35 | 4 | 8 |

| Neutrophils | 7 | 12 | 20 | 35 | 17 | 33 | 11 | 21 |

| Platelets | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 15 | 16 | 31 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Diarrhea without previous colostomy | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Muco/stomatitis (symptom), oral cavity | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Infection with grade 3-4 neutropenia, colon | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Infection with grade 0-2 neutropenia, lung | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Hypocalcemia | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Hyperglycemia | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Hypoglycemia | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Hyponatremia | 5 | 9 | ||||||

| Hyperuricemia | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Neuropathy, sensory | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Syncope | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Dyspnea | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Hypoxia | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Worst degree | 18 | 32 | 22 | 39 | 21 | 40 | 20 | 38 |

Abbreviations: R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

DISCUSSION

Outcomes in MCL have improved, with OS rates of 5 years19 or longer.20 By using R-CHOP as an initial therapy for untreated MCL, Howard et al3 reported a 96% response rate and median PFS of 16 months. In a larger cohort,4 the response rate was 92%, and PFS was 28 months, but these patients received consolidation therapy. Patients with MCL treated in the R-CHOP arm of a randomized trial had a median PFS of 20 months.21 Similar data was reported from a retrospective analysis of patients who received R-CHOP at National Comprehensive Cancer Network institutions22 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Previously Reported Outcomes of R-CHOP As Initial Therapy for MCL

| Reference | No. of Patients | Median Age (years) | Maintenance/Consolidation | Median PFS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Howard et al3 | 40 | 55 | None | 17 |

| Lenz et al4* | 62 | 61 | Interferon | 19 |

| Rummel et al21 | 48 | 70 | None | 22 |

| Lacasce et al22* | 29 | 55 | None | 18 |

| Kluin-Nelemans et al23* | 280 | 70 | ||

| R-CHOP responders only | 79 | Rituximab | 56 | |

| 81 | Interferon | 24 | ||

| Smith et al, this article | 56 | 60 | RIT | 34† |

Abbreviations: MCL, mantle-cell lymphoma; PFS, progression-free survival; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

Selected only R-CHOP treated, non–high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell support populations in these reports.

Reported as time to treatment failure.

Because of the activity of RIT in MCL,13,14 its favorable toxicity profile, and the need for a consolidation treatment applicable to all patients, including older and less-fit patients, this trial tested, as an initial therapy of MCL, an abbreviated four cycles of R-CHOP followed by consolidation with 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan. RIT improved the quality of responses achieved with four cycles of R-CHOP, a cycle number that was selected to ensure the safety and tolerability of subsequent RIT and to allow for the possibility of an RIT crossfire effect. The overall treatment regimen, which was a relatively short-duration, well-tolerated outpatient regimen applicable to most patients with MCL, produced a median TTF of 34.2 months. This median TTF is better than that previously reported for six cycles of R-CHOP.3,21 Not surprisingly, no plateau in PFS is apparent. The baseline MIPI18 score correlated with the outcome. All planned therapy was administered to 52 of 57 enrolled patients, generally within 14 to 18 weeks. No unexpected toxicities were noted. No patient had delayed recovery of blood counts after RIT. Having demonstrated the safety of this brief treatment strategy, RIT consolidation after more-complete cytoreduction, such as after a full-course of R-CHOP or cytarabine- or bendamustine-based regimens, can be investigated. As MCL treatment evolves to more intense regimens in young, fit patients, perhaps RIT consolidation will focus on older patients. Whether RIT consolidation would be more effective and/or more toxic after R-CHOP given for six or eight cycles or on a 14-day cycle remain open questions.

There are theoretic concerns that excess rituximab could block RIT activity24; however, residual rituximab levels from R-CHOP would be minimal compared with levels from the two doses administered before RIT. Surprisingly little is known about optimal unlabeled rituximab levels for RIT.25 Nonetheless, in our study, RIT was clearly active. RIT is also active after R-CHOP for diffuse large–B-cell lymphoma26 and follicular lymphoma with even more rituximab administered.27 In the FIT trial,28 the benefit from RIT consolidation was similar in patients receiving chemotherapy with or without rituximab. Optimization of the amount of pre-RIT unlabeled antibody on the basis of circulating rituximab and residual CD20 targets would be worth future study.

Alternatives to consolidation approaches to improve R-CHOP results include maintenance strategies. Maintenance rituximab prolongs PFS in indolent B-cell lymphoma29 but has been less-well studied in MCL. Rituximab maintenance after single-agent rituximab in a mixed population of patients with untreated or relapsed MCL showed a modest prolongation of event-free survival.30 In relapsed MCL, rituximab maintenance after treatment with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone with or without rituximab31 had modest effects. The initial therapy for MCL with a modified R-CHOP–like regimen followed by rituximab maintenance yielded a median PFS of 37 months.32 In a recently reported trial23 in which patients ≥ 60 years old with MCL were randomly assigned to treatment with R-CHOP or rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (R-FC), R-CHOP was superior to R-FC for response rates and OS. Responding patients were again randomly assigned to receive rituximab or interferon maintenance until progression. The remission duration was prolonged by rituximab maintenance but only after R-CHOP. In the cohort of patients who responded to R-CHOP, the response duration with rituximab maintenance was 56 months compared with 24 months with interferon (P = .001). This differential effect was not seen in patients receiving R-FC, which suggested that maintenance and consolidation effects will vary with the induction strategy. A comparison of RIT consolidation, perhaps followed by maintenance rituximab, with maintenance rituximab alone may be of interest.

R-CHOP for four cycles followed by 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan is a well-tolerated outpatient regimen that can be used to treat most patients with MCL. The 1.5-year TTF of 69% and median TTF of 34.2 months compare favorably with results reported the use of six cycles of R-CHOP (Table 4). Even with new therapeutic backbones such as rituximab plus bendamustine,21 perhaps with bortezomib,33,34 the concept of consolidation with RIT will remain attractive, although for each regimen, the safety and tolerability of subsequent RIT will require clinical trial validation. Even if maintenance rituximab and/or lenalidomid (currently under investigation) become standard, RIT consolidation before maintenance will remain an interesting research question. Currently, in patients who cannot tolerate more-intensive regimens or clinical trials, R-CHOP for four cycles followed by 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan is a reasonable approach to the initial therapy of MCL.

Acknowledgment

Biogen-IDEC supplied 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan for the study.

Footnotes

Written on behalf of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Supported in part by Public Health Service Grants No. CA21115, CA23318, CA66636, CA17145, CA27525, CA14958, and CA21076 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Presented in part at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Atlanta, GA, June 2-6, 2006; the 47th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, December 8-11, 2007; and the 11th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma, Lugano, Switzerland, June 15-18, 2011.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00070447.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Sandra J. Horning, Genentech (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: Leo Gordon, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (C); Randy D. Gascoyne, Roche/Genentech (C); Brad S. Kahl, Genentech (C); Ranjana Advani, Genentech (C) Stock Ownership: Sandra J. Horning, Roche Honoraria: Mitchell R. Smith, Genentech, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals; Randy D. Gascoyne, Roche/Genentech Research Funding: Andres Forero-Torres, Biogen-IDEC; Brad S. Kahl, Genentech; Ranjana Advani, Genentech Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mitchell R. Smith, Brad S. Kahl, Sandra J. Horning

Provision of study materials or patients: Mitchell R. Smith, Leo Gordon, Andres Forero-Torres, Brad S. Kahl, Ranjana Advani, Sandra J. Horning

Collection and assembly of data: Mitchell R. Smith, Hailun Li, Randy D. Gascoyne, Elisabeth Paietta, Brad S. Kahl, Fangxin Hong, Sandra J. Horning

Data analysis and interpretation: Mitchell R. Smith, Hailun Li, Leo Gordon, Randy D. Gascoyne, Elisabeth Paietta, Brad S. Kahl, Fangxin Hong, Sandra J. Horning

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris NL, Jaffé ES, Stein H, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: A proposal from the international lymphoma study group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams ME, Swerdlow SH. Cyclin D1 overexpression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with chromosome 11 bcl-1 rearrangement. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:71–73. doi: 10.1093/annonc/5.suppl_1.s71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard OM, Gribben JG, Neuberg DS, et al. Rituximab and CHOP induction therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma: Molecular complete responses are not predictive of progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1288–1294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: Results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1984–1992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romaguera JE, Fayad LE, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7013–7023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romaguera JE, Fayad LE, Feng L, et al. Ten-year follow-up after intense chemoimmunotherapy with Rituximab-HyperCVAD alternating with Rituximab-high dose methotrexate/cytarabine (R-MA) and without stem cell transplantation in patients with untreated aggressive mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:200–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epner EM, Unger J, Miller T, et al. A multicenter trial of hyperCVAD + rituxan in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma. 49th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 8-11, 2007; Atlanta, GA: (abstr 387) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merli F, Luminari S, Ilariucci F, et al. Rituximab plus HyperCVAD alternating with high dose cytarabine and methotrexate for the initial treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma, a multicentre trial from Gruppo Italiano Studio Linfomi. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, et al. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progression-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: Results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood. 2005;105:2677–2684. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: A nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112:2687–2693. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermine O, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al. Alternating courses of 3x CHOP and 3x DHAP plus rituximab followed by a high dose ARA-C containing myeloablative regimen and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is superior to 6 courses CHOP plus rituximab followed by myeloablative radiochemotherapy and ASCT in mantle cell lymphoma: Results of the MCL younger trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network (MCLnet). 52nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 4-7, 2010; Orlando, FL. (abstr A110) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damon LE, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for untreated patients with mantle-cell lymphoma: CALGB 59909. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6101–6108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M, Oki Y, Pro B, et al. Phase II study of yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5213–5218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zelenetz AD, Noy A, Pandit-Taskar N, et al. Sequential radioimmunotherapy with tositumomab/iodine I131 tositumomab followed by CHOP for mantle cell lymphoma demonstrates RIT can induce molecular remissions. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:436s. (suppl; abstr 7560) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grever MR, Lucas DM, Dewald GW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of genetic and molecular features predicting outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results from the US Intergroup Phase III Trial E2997. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:799–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.[no authors listed]. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:558–565. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrmann A, Hoster E, Zwingers T, et al. Improvement of overall survival in advanced stage mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:511–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al. Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1209–1213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab is superior in respect of progression free survival and cr rate when compared with CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment of patients with advanced follicular, indolent, and mantle cell lymphomas: Final results of a randomized phase iii study of the StiL (Study Group Indolent Lymphomas, Germany). 51st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 5-8; New Orleans, LA. 2009. (abstr 405) [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaCasce AS, Vandergrift JL, Rodriguez MA, et al. Comparative outcome of initial therapy for younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: An analysis from the NCCN NHL Database. Blood. 2012;119:2093–2099. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kluin-Nelemans JC, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al. R-CHOP versus R-FC followed by maintenance with rituximab versus interferon-alfa: Outcome of the first randomized trial for elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011:118. (abstr 439) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopal AK, Press OW, Wilbur SM, et al. Rituximab blocks binding of radiolabeled anti-CD20 antibodies (Ab) but not radiolabeled anti-CD45 Ab. Blood. 2008;112:830–835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Illidge TM, Bayne M, Brown NS, et al. Phase 1/2 study of fractionated (131)I-rituximab in low-grade B-cell lymphoma: The effect of prior rituximab dosing and tumor burden on subsequent radioimmunotherapy. Blood. 2009;113:1412–1421. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-175653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zinzani PL, Rossi G, Franceschetti S, et al. Phase II trial of short-course R-CHOP followed by 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan in previously untreated high-risk elderly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3998–4004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Markus TM, et al. Rituximab plus short-duration chemotherapy followed by Yttrium-90 Ibritumomab tiuxetan as first-line treatment for patients with follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A phase II trial of the Sarah Cannon Oncology Research Consortium. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9:223–228. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.n.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, et al. Phase III trial of consolidation therapy with yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan compared with no additional therapy after first remission in advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5156–5164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): A phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:42–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghielmini M, Schmitz S-FH, Cogliatti S, et al. Effect of single-agent rituximab given at the standard schedule or as prolonged treatment in patients with mantle cell lymphoma: A study of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:705–711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: Results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) Blood. 2006;108:4003–4008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahl B, Longo WL, Eickhoff, JC, et al. Maintenance rituximab following induction chemoimmunotherapy may prolong progression-free survival in mantle cell lymphoma: A pilot study from the Wisconsin Oncology Network. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1418–1423. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedberg JW, Vose JM, Kelly JL, et al. The combination of bendamustine, bortezomib, and rituximab for patients with relapsed/refractory indolent and mantle cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:2807–2812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-314708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fowler N, Kahl BS, Lee P, et al. Bortezomib, bendamustine, and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: The phase II VERTICAL study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3389–3395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]