Abstract

Background

Despite the frequent occurrence of pleural effusions in lung transplant recipients, little is known about early posttransplant pleural space infections. We sought to determine the predictors and clinical significance of pleural infection in this population.

Methods

We analyzed 455 consecutive lung transplant recipients and identified patients that underwent sampling of pleural fluid within 90 days posttransplant. A case control analysis was performed to determine the characteristics that predict infection and the impact of infection upon posttransplant survival.

Results

Pleural effusions undergoing drainage occurred in 27% of recipients (124/455). Ninety-six percent of effusions were exudative. Pleural space infection occurred in 27% (34/124) of patients with effusions. The incidence of infection did not differ significantly by native lung disease or type of transplant operation. Fungal pathogens accounted for over 60% of the infections; Candida albicans was the predominant organism. Bacterial etiologies were present in 25% of cases. Infected pleural effusions had elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (p=0.036) and markedly increased neutrophils in the pleural space (p<0.0001) as compared to noninfected effusions. A pleural neutrophil percentage of >21% provides a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 79% for correctly identifying infection. Patients with pleural space infection had diminished one year survival as compared to those without infection (67% vs. 87%, respectively, p=0.002).

Conclusion

Pleural infection with fungal or bacterial pathogens commonly complicates lung transplantation and elevated neutrophils in the pleural fluid is the most sensitive and specific indicator of infection.

Keywords: Effusions, Empyema, Neutrophils, Lung Transplantation

Introduction

Although infection represents a leading cause of death over the first year after lung transplantation 1, little is known regarding the risk factors, microbial etiology, or clinical significance of early posttransplant pleural space infection in the lung transplant population. Moreover, the specific pleural fluid characteristics that predict infection and the value of Light’s criteria in assessing the etiology of the effusion have not been evaluated in the early postoperative lung transplant recipient. Prior reports suggest pleural effusions can develop in the early postoperative period after lung transplantation both in the presence and absence of allograft rejection.2,3 Additionally, one prior report found only a 4% incidence of empyema among lung transplant recipients primarily from bacterial etiologies.4 In contrast, we have determined that there is a higher incidence of pleural infection in the early postoperative period and that these infections are more likely due to atypical or fungal pathogens. Herein, we report our systematic analysis of the incidence, pleural fluid characteristics, microbiology, and clinical outcome of patients who develop pleural space infection early after lung transplantation.

Methods

Patients

We performed an IRB approved review of all lung transplant recipients at Duke University Medical Center between January 1996 and August 2005. Patients who underwent pulmonary retransplant (n=19), native lung transplant after prior single-lung transplant of the opposite lung (n=1), or living lobar transplant (n=7) were excluded from the analysis because of their unique pleural space characteristics. Patients who received multiple organ transplants and patients who died within 72 hours postoperatively (n=7) were also excluded. We analyzed the records of 455 consecutive cadaveric lung transplant recipients that met inclusion criteria and identified every instance in which a patient underwent sampling of pleural fluid within the first 90 days posttransplant.

Patient demographics, pleural fluid characteristics and serum laboratory values obtained within ten days of the thoracentesis were recorded (if multiple thoracenteses were performed, the initial values were used). All laboratory values were not available for all events (exact number included for each analysis). Protein levels recorded as <2.0 g/dL were considered to be 1.9 g/dL and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels recorded as <100 U/L were considered to be 99 U/L for purpose of statistical analysis. Effusions were classified as an exudate if any of Light’s criteria were met: 1) Pleural protein to serum protein ratio of greater than 0.5, 2) Pleural LDH to serum LDH ratio of greater than 0.6, or 3) an absolute LDH of greater than 133 U/L (2/3 the upper limit of normal serum LDH (200 U/L) at our reference laboratory).5

Transplant procedure and postoperative management protocol

Details of the transplant procedure and postoperative management have been described in detail previously.6,7 During the study period, patients received triple immunosuppression with cyclosporine (prior to 2001) or tacrolimus (after 2001), azathioprine and methylprednisolone followed by prednisone. Since 1999 patients also received basiliximab perioperatively. Transplant recipients received ceftazidime and vancomycin prophylaxis perioperatively for two weeks or specific antimicrobial prophylaxis adjusted for known preoperative pathogens or donor culture results for two to three weeks. CMV prophylaxis with intravenous ganciclovir was given based on the CMV status of the donor and recipient. Patients received inhaled conventional or liposomal amphotericin B daily for four days and then weekly while in the hospital for fungal prophylaxis. No azole antifungal agents were routinely used as prophylaxis during the study period.

Chest tubes were routinely removed from patients within seven days after surgery. A drainage procedure was performed on any lung transplant patient who developed a new or increasing pleural effusion visible on portable or PA and lateral chest x-ray. Ultrasound was not used to screen for the presence of pleural effusions in these patients, but was routinely used to guide thoracentesis. Patients receive chest radiographs daily postoperatively, weekly for the first month after discharge and then monthly over the first year. If clinical indications developed, additional radiographic studies were pursued. A freshly obtained sample of pleural fluid was submitted for microbiology culture in sterile plastic tubes; special culture bottles with media were not utilized. If a pleural space infection was not completely drained by the thoracentesis procedure, then a chest tube was placed. In cases where loculated fluid was not adequately drained by the chest tube then VATS or open decortication was performed. Patients with pleural space infections received antimicrobial therapy directed against the cultured pathogen or empiric broad spectrum antibiotics in the case of the two sterile pleural space infections.

Definition of pleural space infection

Pleural space infection was defined as any pleural effusion with a positive bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, or viral culture for a pathogenic organism obtained from the normally sterile pleural space or as a negative culture accompanied by the presence of frank pus in the pleural space (>20,000 total nucleated cells/cm2). Separate effusions or pleural space infections in the same patient were defined as two distinct events if occurring with different organisms or if separated by at least one month.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SAS (9.1, Cary, NC) and GraphPad (4.02, San Diego, California) software. Results are reported as mean±standard error (SE) or median and interquartile range (IQR). The fluid characteristics of effusions and pleural space infections were compared using a two-sided Student’s t-test with equal or unequal variance, as appropriate. Dichotomous variables were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Data were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and one year survival was compared using the Log Rank test. Patients were right-censored at one year for survival analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated using SAS logistic regression and GraphPad ROC functions.

Results

Demographic characteristics

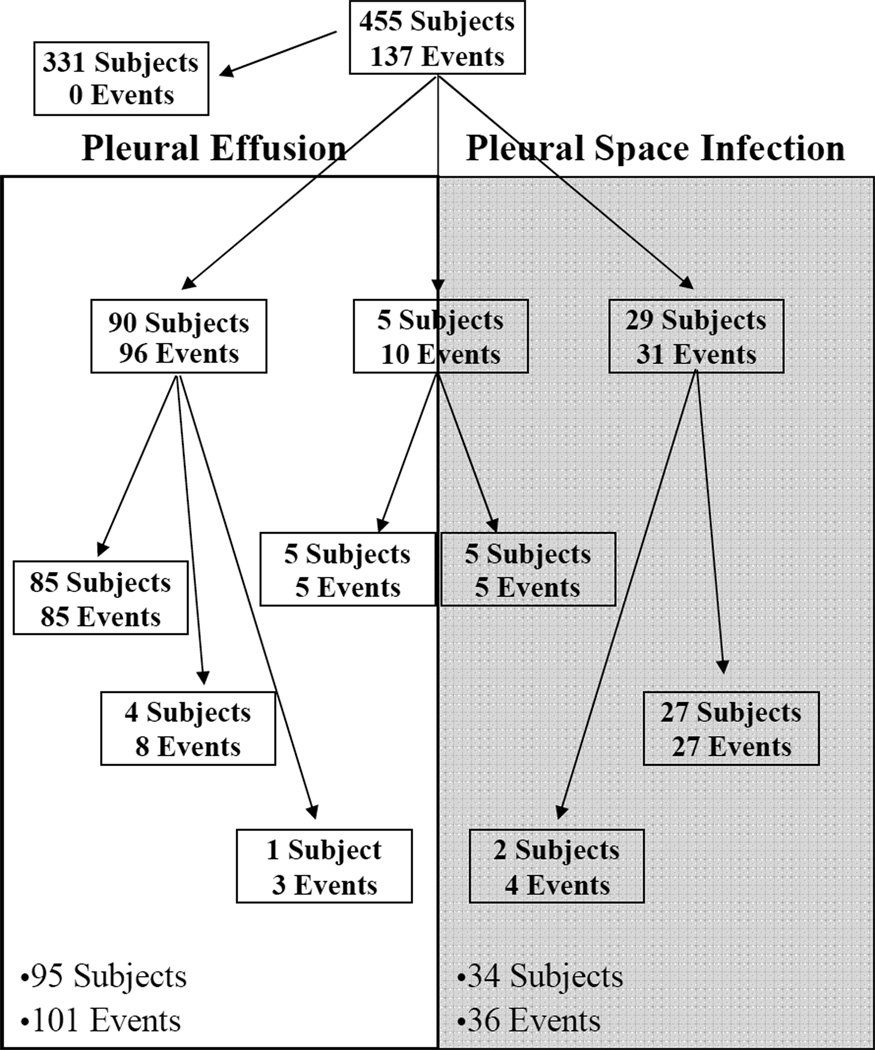

A total of 101 noninfected effusion events occurred in 95 patients and 36 pleural space infection events occurred in 34 patients for a total of 137 effusion events in these 124 patients. Five patients had an effusion event separated in time from a pleural space infection event (and are counted as having both a noninfected effusion event and a pleural space infection), five subjects had multiple effusion events (all of which were noninfected) and two subjects had multiple pleural space infection events, as summarized in Figure 1. Early posttransplant pleural effusions, thus, occurred in 27% (124/455) of lung transplant recipients. The majority of effusions were free of infection; however, 27% (34/124) of patients with effusions had pleural space infections. The demographic characteristics of the patients with noninfected posttransplant effusions are similar to those in patients with pleural space infections (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in the age, gender, native disease, type of transplant operation or days to the first clinical intervention between those patients who developed an infected pleural effusion and those free from infection. The rate of pleural space infection was not increased in patients with septic lung disease (p=0.81). A trend, however, was observed towards increased risk for pleural space infection in patients who underwent bilateral as compared to single lung transplantation (p=0.06). The time from transplant to thoracentesis in patients with pleural space infection ranged from 7 to 88 days with a median of 28 days (21–38 days, IQR).

Figure 1.

Distribution of pleural space effusions and infections among lung transplant recipients. 101 noninfected pleural effusion events (unshaded) occurred in 95 subjects and 36 pleural space infection events (shaded) occurred in 34 subjects.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of lung transplant recipients by effusion group.

| Effusion (n=90) | Pleural Space Infection (n=34) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SE) | 51±1 | 52±2 | 0.81 |

| Gender | 0.15 | ||

| Male | 56% (n=50) | 71% (n=24) | |

| Female | 44% (n=40) | 29% (n=10) | |

| Type of Transplant Operation | 0.06 | ||

| Single | 21% (n=19) | 6% (n=2) | |

| Bilateral | 79% (n=71) | 94% (n=32) | |

| Native Disease Type | |||

| Septic | 21% (n=19) | 24% (n=8) | 0.81* |

| Obstructive | 50% (n=45) | 38% (n=13) | |

| Fibrotic | 21% (n=19) | 26% (n=9) | |

| Other | 8% (n=7) | 12% (n=4) | |

| Mean days to 1st effusion analysis (+SE) | 36±2 | 34±4 | 0.55 |

p-value compares septic lung disease v. pooled results from other native disease types

Patient management and outcomes

All pleural space infections were managed with drainage and appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Six (17%) pleural space infections were drained fully with thoracentesis alone. In addition, 24 (67%) were managed with chest tube drainage (2 were the initial postoperative chest tubes). Finally, 6 (17%) pleural space infections were managed with Video Assisted Thorascopic Surgery (VATS) or open surgical decortication.

Pleural fluid characteristics

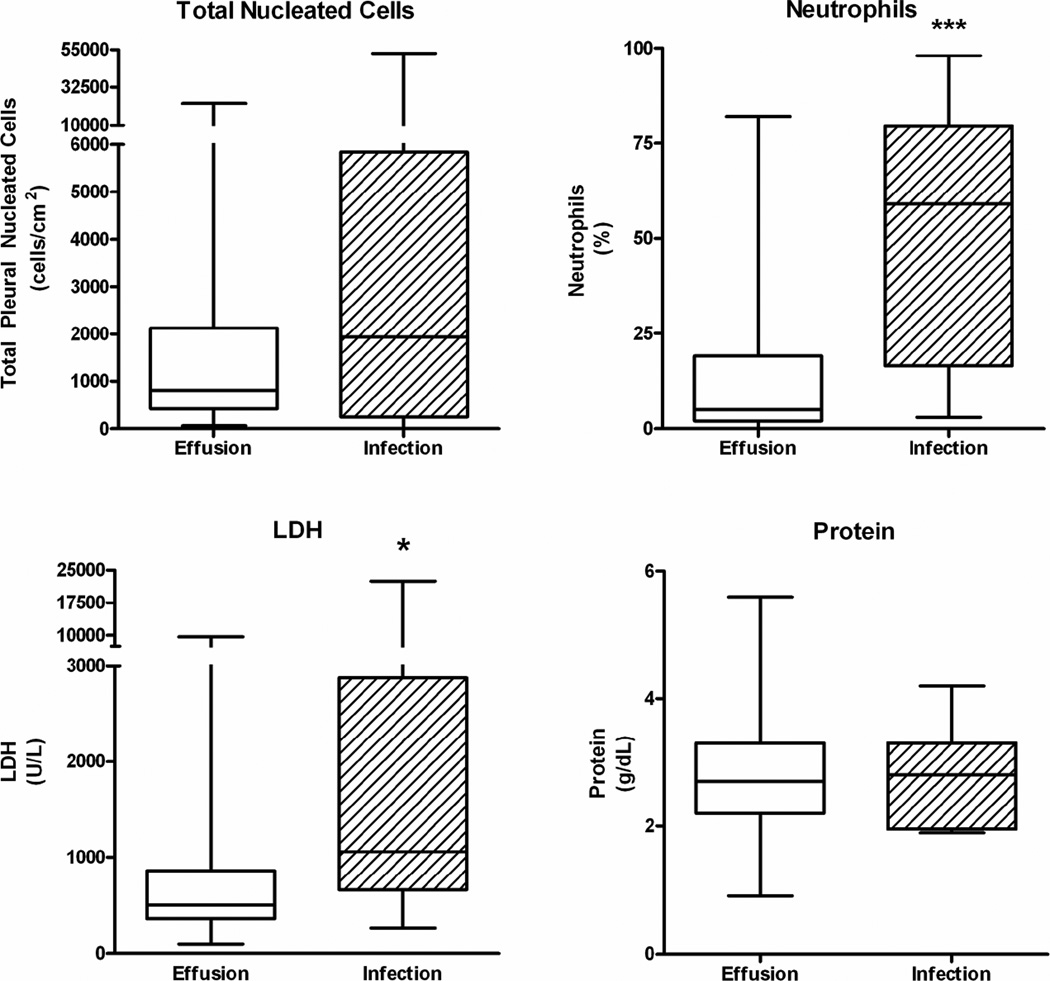

The characteristics of the effusions in patients with pleural space infection were compared to those in patients with effusions free from infection. The mean and standard error of each variable and total number of patients in which each test was performed was recorded in Table 2 and, for many variables, there was little difference in the fluid characteristics; there was no significant difference in pleural protein, pleural glucose, pleural pH, pleural protein/serum protein ratio, pleural LDH/serum LDH ratio or total nucleated cells. Among all of the effusions and pleural space infections with laboratory chemistries, 96% (114/119) met at least one of Light’s criteria for an exudate. As shown in Table 2,96% of effusions were exudative among both patients with pleural space infection (27/28) and those without pleural space infection (87/91). A trend towards increased LDH ratio, protein ratio, reduced pH, reduced glucose, and increased total nucleated cells was observed with infected as compared to noninfected effusions.

Table 2.

Comparison of pleural fluid and serum characteristics in patients with pleural space infections and noninfected pleural effusions

| Effusion | Pleural Space Infection | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleural LDH (U/L) (n=115) | 889±142 (n=89) | 3236±1049 (n=26) | 0.04 |

| LDH ratio (n=65) | 1.36±0.335 (n=47) | 4.24± 1.48 (n=18) | 0.07 |

| Pleural Protein (g/dL) (n=119) | 2.85±0.10 (n=91) | 2.75±0.74 (n=28) | 0.59 |

| Protein ratio (n=55) | 0.51±0.02 (n=40) | 0.59±0.04 (n=15) | 0.06 |

| Exudate (n=114) | 96% (n=87) | 96% (n=27) | 1.00 |

| Pleural Glucose (mg/dL) (n=98) | 125±5.85 (n=73) | 105±10.7 (n=25) | 0.08 |

| Pleural pH (n=88) | 7.46±0.01 (n=67) | 7.37±0.04 (n=21) | 0.07 |

| Total Pleural Nucleated Cells (cells/cm2) (n=119) | 2075±433 (n=89) | 5637±1980 (n=30) | 0.09 |

| Pleural Lymphocytes (%) (n=119) | 65±2.7 (n=89) | 34±5.6 (n=30) | <0.0001 |

| Pleural Neutrophils (%) (n=119) | 16±2.2 (n=89) | 51±5.9 (n=30) | <0.0001 |

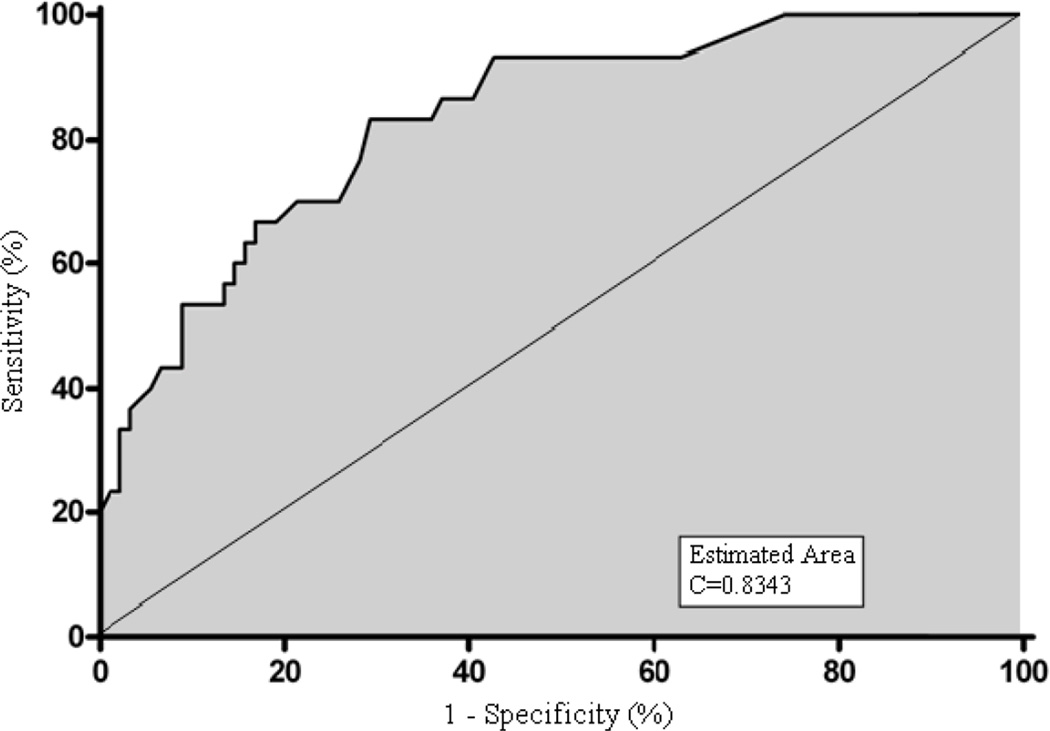

In contrast, the pleural LDH was significantly increased in patients with pleural space infection as compared to noninfected effusion (3236±1049 U/L vs. 889±142 U/L, respectively, p=0.036). Furthermore, highly significant differences between infected and noninfected pleural effusions were observed in the cell differential count. A marked increase in the neutrophil percentage was observed in the infected pleural spaces as compared to noninfected effusions (51±6% vs. 16±2%, respectively, p<0.0001). This highly significant difference is illustrated in Figure 2. In addition, a marked reduction in the lymphocyte percentage was observed in the pleural space infections as compared to the noninfected effusions (34±6% vs. 65±3%, respectively, p<0.0001). Furthermore, a ROC curve constructed from the neutrophil differential counts demonstrates that pleural neutrophil percentage is a sensitive and specific diagnostic criteria which is useful in identifying the presence of a pleural space infection within three months of transplantation in a lung transplant recipient (Figure 3, c-value=0.84). Analysis suggests a cutoff point of >21% neutrophils provides a reasonable sensitivity and specificity for correctly identifying pleural fluid infection (70% and 79%, respectively) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Impact of Pleural Space Infection on Total Pleural Nucleated Cells, Neutrophil Differential Count, Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), and Protein (*p<0.05, *** p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve of Differential Neutrophil Counts and Pleural Space Infection (c=0.8343).

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity in the detection of pleural space infection based on % Neutrophils

| Neutrophils (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| >8 | 93 | 57 |

| >15 | 83 | 71 |

| >21 | 70 | 79 |

| >40 | 60 | 85 |

| >60 | 47 | 91 |

Microbiology

A total of fifteen pathogens were isolated from 36 pleural space infection events that occurred in 34 lung transplant recipients. Two patients had episodes of infection with multiple pathogens and two patients were included with negative cultures but frank pus in the pleural fluid (52,869 total nucleated cells/cm2 and 28,200 total nucleated cells/cm2,respectively).

The predominant organism cultured from the pleural fluid was Candida albicans, which accounted for 44% (n=16) of all pleural space infections. No other pathogen was cultured from more than 6% (n=2) of patients (Table 4). Fungal species caused 61% (n=22) of pleural space infections, while bacterial species were responsible for 25% (n=9) of the cases, predominately due to gram negative pathogens. Atypical causes of pleural infection included Mycoplasma hominis (n=2) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (n=1).

Table 4.

Microbial etiology of pleural space infection

| Fungal Species | 61% (n=22) | Bacterial Species | 25% (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | n=2 | Burkholderia cepacia | n=2 |

| Candida albicans | n=16 | Enterococcus species | n=1 |

| Candida parapsilosis | n=1 | Escherichia coli | n=1 |

| Candida glabrata | n=2 | Klebsiella oxytoca | n=1 |

| Candida tropicalis | n=1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | n=1 |

| Roseomonas species | n=1 | ||

| Serratia marcescens | n=1 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | n=1 | ||

| Other Pathogens | 8% (n=3) | Culture Negative Pleural Infection | 6% (n=2) |

| Mycoplasma hominis | n=2 | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | n=1 | ||

Survival Analysis

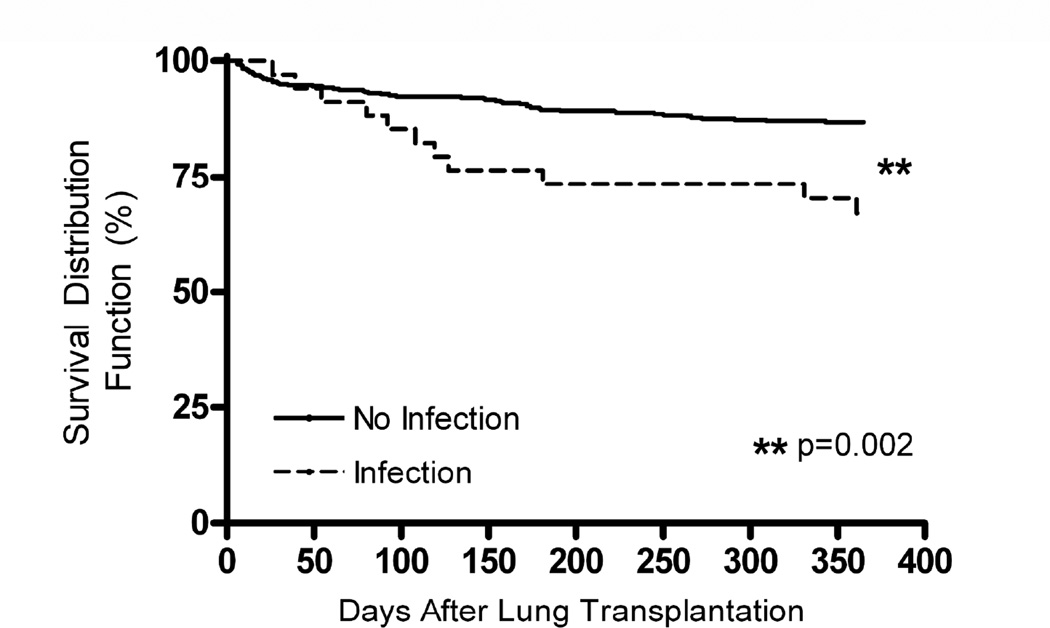

One year posttransplant survival was 86% in patients without an effusion, 91% in patients with effusions in the absence of an infection, and 67% in patients with pleural space infection (p=0.0034, 3 way comparison, Log-Rank test). There was no significant difference in the one year posttransplant survival of patients without an effusion and patients with an effusion which occurred in the absence of pleural space infection (p=0.16), demonstrating the presence of an effusion in the absence of infection did not alter survival. Therefore, the one year survival of patients with noninfected effusions or no effusions (No Infection group, Figure 4) was significantly improved as compared to the one year posttransplant survival of patients with a pleural space infection (Infection group, Figure 4) (p=0.002). In patients with pleural space infection who died (n=11), one died of a non-infectious complication, one died of progressive pulmonary Aspergillosis (the same pathogen as cultured from the pleural space) and 82% (n=9) died from sepsis with multiple organ system failure. In 67% (6/9) of these patients, the following pathogen was cultured from the blood and the pleural fluid: Candida albicans (n=2), Candida glabrata (n=1), Burkholderia cepacia (n=1), Staphylococcus aureus (n=1), Serratia marcescens (n=1). The time from initial sampling to death in these 6 patients with the same pathogen cultured from the blood and the pleural space and the one patient with pulmonary and pleural Aspergillosis was a median of 43 days (20–54 days, IQR). In the other three patients who died of sepsis, one patient had Candida albicans cultured from their pleural fluid but no blood cultures, one had Candida albicans cultured from their pleural fluid and Candida glabrata cultured from their blood, and one had Candida parapsilosis cultured from their pleural fluid and Burkholderia cepacia cultured from their blood.

Figure 4.

Impact of pleural space infection on survival after lung transplantation. One year survival of patients free from pleural space infection is significantly greater than those patients with early posttransplant pleural space infection 87% vs. 67%, respectively, p=0.002, Log Rank test.

Discussion

We present a comprehensive analysis of early pleural space infection in lung transplant recipients. Pleural effusions occur in 25% of patients within the first 90 days after lung transplantation. Likely mechanisms for effusions during this early postoperative period include increased alveolar permeability, perioperative pleural inflammation, postoperative atelectasis and impaired lymphatic drainage, as has been suggested previously.2,8,9 In addition, the host alloimmune response to the transplant could also contribute to the development of effusions. Furthermore, pleural space infection occurs in over one quarter of patients with early posttransplant effusions. We found clinical characteristics (type of transplant operation or native lung disease) were not significant predictors of pleural space infection.

In contrast, we identified several pleural fluid characteristics that were useful in identifying patients with pleural infection. An increased pleural LDH and particularly an increased neutrophil percentage among the total pleural cells is highly predictive indicator of pleural space infection in this population. The ROC analysis demonstrates that a neutrophil percentage of >21% provides a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 79% for correctly identifying infection (Table 3). Although using a much higher cutoff, such as 60% neutrophils, would increase the specificity to over 90% it would reduce the sensitivity to only 47%. Our results emphasize the importance of pursing appropriate microbiological cultures in all early posttransplant effusions and highlight that a finding of increased neutrophils should raise the suspicion of a pleural space infection.

A surprising finding in our analysis was that traditional pleural markers, such as the distinction between transudate and exudate, are of little value in the transplant population because the majority of all early posttransplant effusions are exudative. In the non-transplant setting, classification of a pleural effusion as a transudate or exudate (commonly performed using Light’s criteria) provides valuable clues to the etiology of the effusion. In the early posttransplant setting, we found that over 95% of the effusions in our study were exudative by Light’s criteria. Thus, this distinction does not provide clinically useful information regarding the risk for pleural space infection. This observation is consistent with much smaller previous reports that suggest early posttransplant effusions tend be exudative even in the absence of infection or rejection.2,3

Prior reports have also suggested that lymphocystosis of the pleural fluid is nonspecific early after transplant and occurs both in patients free from rejection or with acute allograft rejection.3,9,11 Similarly, we observed a majority of noninfected effusions demonstrate a lymphocytic predominance which may reflect the normal host response and lymphocyte trafficking through the newly transplanted allograft lung. We did not attempt to correlate the presence of lymphocytosis with rejection in our analysis given that many patients did not undergo concurrent lung biopsy and that our focus was upon risk factors and significance of pleural space infection. The relationship between these pleural characteristics and allograft rejection certainly represents an interesting area for future studies.

Another novel observation of our study is the high percentage of fungal pleural space infections early after lung transplantation which contrasts with previous smaller studies of posttransplant pleural effusions.4 The increase in the percentage of pleural infections due to fungal etiologies as compared to previous studies might reflect our bacterial prophylaxis practices and our consistent approach to pursue fungal cultures in all effusions. In addition, our results might reflect the increasing importance of Candida species as a nosocomial pathogen in the intensive care unit (ICU). Candida species now account for a significant percentage of nosocomial bloodstream infections.12,13 Recently, pleural space nosocomial infections with Candida species have been described in critically ill patients.14

Compromised host defense early after transplantation due to immunosuppression and the presence of multiple chest tubes might provide a portal for Candida species and other opportunistic pathogens to enter into the pleural space and cause infection. The standard prophylactic antibiotic regimen and immunosuppression (including induction) posttransplant may predispose these patients to fungal infections due to the compromised host defenses and paucity of competing bacterial species. In all our patients, our center employed standard antifungal prophylaxis with inhaled amphotericin B.15 Over 60% of lung transplant centers use a similar approach with inhaled amphotericin B.16 However, the inhaled approach, while minimizing side effects, might be less effective in the prevention of fungal pleural space infection than systemic antifungal agents.

All patients with pleural space infection received an aggressive management approach which included drainage of the infected pleural space and appropriate antibiotics directed at the specific pleural space microbiology.17 Despite this approach, our results demonstrate that pleural space infection is associated with significantly worse posttransplant survival. Early pleural space infection thus identifies patients at increased risk for additional complications and one year mortality. Although we cannot attribute these patient deaths directly to the pleural space infection, the cause of death in 82% (9/11) of patients was sepsis. Furthermore, a pathogen cultured from the blood was identical to the pathogen cultured from the pleural fluid in 67% (6/9) of these patients, suggesting a relationship between disseminated infection, pleural infection and death in these patients.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature which hindered our ability to look at other risk factors for developing post-transplant pleural effusions such as the size mismatch between the transplanted lung and the recipient chest cavity, or the relationship between effusions and concurrent allograft rejection. Additionally, although our policy is to sample all newly developed or enlarging pleural effusions in lung transplant recipients we can not, given the retrospective nature of the study, be absolutely certain that all effusions were sampled, which may have affected the observed incidence of effusions and pleural space infections. A prospective analysis in lung transplant recipients with pre-defined criteria for identification, sampling and management of pleural space infection as well as concurrent lung biopsy at the time of effusion would be useful to extend our findings.

In summary, pleural space infection occurs in one fourth of lung transplant recipients who develop early posttransplant effusions. Clinical characteristics are of limited utility in identifying patients with pleural space infection. A very high neutrophil component of the pleural cell differential has the greatest specificity for identifying the presence of pleural space infection. Because the presence of infection is associated with worse posttransplant survival, aggressive approaches to prevention, diagnosis and management should be further evaluated.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL69978) and Departmental funds

REFERENCES

- 1.Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-third Official Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report--2006. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2006;25:880–892. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shitrit D, Izbicki G, Fink G, et al. Late postoperative pleural effusion following lung transplantation: characteristics and clinical implications. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2003;23:494–496. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Judson MA, Handy JR, Sahn SA. Pleural effusion from acute lung rejection. Chest. 1997;111:1128–1130. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunley DR, Grgurich WF, Keenan RJ, et al. Empyema complicating successful lung transplantation. Chest. 1999;115:1312–1315. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, et al. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates.[see comment] Annals of Internal Medicine. 1972;77:507–513. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau CL, Palmer SM, D'Amico TA, et al. Lung transplantation at Duke University Medical Center. Clinical Transplants. 1998:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadjiliadis D, Duane Davis R, Steele MP, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in lung transplant recipients. Clinical Transplantation. 2003;17:363–368. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veith FJ, Koerner SK, Siegelman SS, et al. Recognition and treatment of rejection in experimental and human lung allografts. Transplantation Proceedings. 1973;5:783–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Judson MA, Handy JR, Sahn SA. Pleural effusions following lung transplantation. Time course, characteristics, and clinical implications. Chest. 1996;109:1190–1194. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.5.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herridge MS, de Hoyos AL, Chaparro C, et al. Pleural complications in lung transplant recipients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:22–26. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(05)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judson MA, Sahn SA. The pleural space and organ transplantation. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 1996;153:1153–1165. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent S, et al. Nosocomial Bloodstream Infections in US Hospitals: Analysis of 24,179 Cases from a Prospective Nationwide Surveillance Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yapar N, Uysal U, Yucesoy M, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections associated with Candida species in a Turkish University Hospital. Mycoses. 2006;49:134–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko S-C, Chen K-Y, Hsueh P-R. Fungal Empyema Thoracis : An Emerging Clinical Entity. Chest. 2000;117:1672–1678. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer SM, Drew RH, Whitehouse JD, et al. Safety of aerosolized amphotericin B lipid complex in lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2001;72:545–548. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108150-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dummer JS, Lazariashvilli N, Barnes J, et al. A survey of anti-fungal management in lung transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2004;23:1376–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marom EM, Palmer SM, Erasmus JJ, et al. Pleural effusions in lung transplant recipients: image-guided small-bore catheter drainage. Radiology. 2003;228:241–245. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281020847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]