Abstract

In order to establish a human challenge model of Shigella related disease for vaccine testing, a dose-escalating inpatient trial was performed. Three groups of 12 healthy adult volunteers were orally challenged with 93,440 and 1680 CFU of Shigella sonnei strain 53G. Subjects were admitted to the Vaccine Trial Centre (VTC) at Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand. The primary purpose of this study was to identify the dose of S. sonnei 53G required to elicit clinical disease in at least 70% of Thai adult subjects. At the highest dose of 1680 CFU, the attack rate was 75%, while at the two lower doses, the attack rate was approximately 50%. This human challenge model, which is the first of its kind in an endemic region, will provide an opportunity for S. sonnei vaccine evaluation in endemic populations.

Keywords: Shigella, Human challenge model, Shigella vaccine

1. Introduction

Shigella infections remain a significant global health concern with an estimated 90 million episodes and 108,000 deaths per year [1]. In Thailand the incidence in children under 5 was reported as 4/1000/year with Shigella sonnei predominant accounting for over 80% of all episodes [2]. Increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance [3,4] and long term sequelae of Shigella infections [5–7] are also of concern. With limited viable treatment options and the problem significance, the need for effective vaccines is growing.

Humans are the only natural host for Shigella spp., although Shigella related disease have been shown to occur in primate models using several-log higher infective doses [8]. The lack of an appropriate animal model leads to the need for a safe and reproducible human challenge model. Previous S. sonnei experimental challenge studies were conducted in the U.S. [9–11] but have not been documented in endemic regions where Shigella vaccines to prevent Shigella related disease would be targeted. This study establishing a human challenge model in Thailand will provide an opportunity for evaluating S. sonnei vaccine candidates in an endemic area.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical review

The study was approved by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s Human Subjects Research Review Board; the Ethical Review Committee for Research in Human Subjects, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand; and the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University.

2.2. Subjects

Healthy Thai adults aged 20–40 years were recruited from the Bangkok Metropolitan region. Written informed consent and assessment of understanding were required before enrollment. Subjects were screened for significant illnesses or pregnancy by history, physical examination and laboratory results. Other exclusion criteria included the presence of anti-S. sonnei lipopolysaccharide (LPS) IgG antibody titers >1:800 [12] or Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) B27.

2.3. Study design

The objective of this study was to identify the dose of S. sonnei 53G required to elicit clinical diseases in at least 70% of healthy Thai adults after oral challenge. The trial consisted of three sequential cohorts, each with 12 subjects. Subjects were admitted to the Vaccine Trial Centre and challenged orally with approximately 100, 400, or 1600 colony forming units (CFU) of S. sonnei 53G. Subjects ingested S. sonnei 53G inoculum suspended in 30 mL of sterile water preceded by drinking 150 mL of sodium bicarbonate buffer to neutralize gastric acidity [13]. During the inpatient stay, subjects were monitored daily for adverse events, gastrointestinal (including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, tenesmus, and diarrhea/dysentery) or other systemic symptoms. Stool samples were collected to determine shedding of S. sonnei 53G and occult blood. Blood samples were collected for evaluation of immune responses.

On Day 5 after challenge, 500 mg of ciprofloxacin twice daily for 3 days was administered. Subjects were released between Days 8 and 11 and returned on Days 14 and 28 for outpatient assessments. A telephone call on Day 42 was conducted to assess the presence of sequelae, specifically joint pains or arthritis.

2.4. Preparation of challenge strain

S. sonnei 53G was initially isolated from a child with diarrhea in Tokyo in 1954. The seed was maintained at the Center for Vaccine Development, University of Maryland. A master cell bank (MCB) (BPR-327-00, Lot 0593) was manufactured by the Pilot Bioproduction Facility, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), Silver Spring, MD, U.S. [9]. The production cell bank (PCB), Lot AS140406 was prepared from frozen vials of MCB sent to Thailand and further characterized for purity, stability, and invasiveness. The PCB was streaked on Congo Red agar and red colonies were tested for agglutination with form I S. sonnei antisera (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) after incubation. Six form I colonies were suspended in 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and plated for confluent growth. On Day 0, bacteria were suspended in PBS and adjusted to OD600 of 0.10, 0.40, and 0.16 corresponding to 1.0 × 108, 4.3 × 108, and 1.6 × 108 CFU/mL, respectively. Serial 10-fold dilutions were performed to obtain final target inoculums of 100, 400 and 1600 CFU/mL. Immediately before challenge, 1 mL of each target inoculum was added to 30 mL sterile water for each subject.

2.5. Laboratory tests

2.5.1. Colony count of challenge inoculum

Two milliliters of each inoculum dose was reserved for pre and post challenge quantitation. Before and after challenge, three Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) were inoculated with 0.25, 0.25, and 0.1 mL of 100, 400, and 1600 CFU inoculums, respectively. After incubation, average numbers of colonies on each TSA plate were calculated to CFU/mL.

2.5.2. Stool culture

All stools were evaluated for weight and presence of blood or mucus and graded on consistency. The first normal stool and up to two abnormal stools per day were collected for culture and PCR. Rectal swabs were collected when stool samples were unavailable. Rectal or stool sample swabs stored in Cary Blair transport medium were processed 4–24 h after collection by direct inoculation onto Hektoen Enteric Agar. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, up to ten non-lactose-fermenting (NLF) colonies were selected and tested by agglutination with S. sonnei antiserum (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). If none of the NLF colonies agglutinated in the Group D antiserum, a representative colony was inoculated in biochemical media for identification.

2.5.3. PCR detection of S. sonnei 53G

DNA templates were prepared using QiaAmp Stool Purification kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). PCR followed by gel electrophoresis to detect a 1644 bp amplified product was applied [14].

2.5.4. Antibody-secreting cells (ASC)

S. sonnei LPS specific IgA, IgM and IgG ASC per 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) on Days 0, 7 and 9 were enumerated by ELISPOT as previously described [15,16]. Positive responses were ASC counts on Day 7 and/or 9 greater than mean + 3 SD of ASC count on Day 0 or ≥10 ASC per 106 PBMC when the count on Day 0 is 0.

2.5.5. Serum antibody responses

Blood samples collected at Days 0, 14 and 28 were tested for IgA, IgM, and IgG antibody responses against S. sonnei LPS by ELISA [16,17]. Seroconversion was defined as ≥4 fold increase on Days 14 and/or 28 compared to Day 0.

2.6. Study-specific definitions

The clinical disease endpoint was defined as diarrhea, dysentery, and/or fever. Diarrhea was defined as two or more grade 3, 4, or 5 stools within 48 h totaling ≥200 mL in volume or a single grade 3, 4, or 5 stool ≥300 mL in volume. Dysentery was defined as a stool of grade 3, 4, or 5 with visible blood. Shigellosis was defined as diarrhea and/or dysentery accompanied by a fever of ≥38.3 °C, one or more severe intestinal symptoms, and shedding of S. sonnei. Severity of symptoms was graded as mild with symptoms present but subject activity levels unchanged; moderate with activity reduced but subjects able to function; and severe with markedly reduced activity and subjects bedridden.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Among the three cohorts, the mean age of subjects was compared by one-way ANOVA, the gender distribution and education levels were compared by Fisher’s exact test, and the median baseline IgG antibody titers were compared by a non-parametric equality-of-medians test using Stata 10 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Dose related linear trend was measured by Jonckheere-Terpstra test comparing frequency of seroconversion or positive ASC responses and linear by linear association test comparing antibody titers or ASC counts using StatXact 8 (Cytel Studio, Cambridge, MA, USA).

3. Results

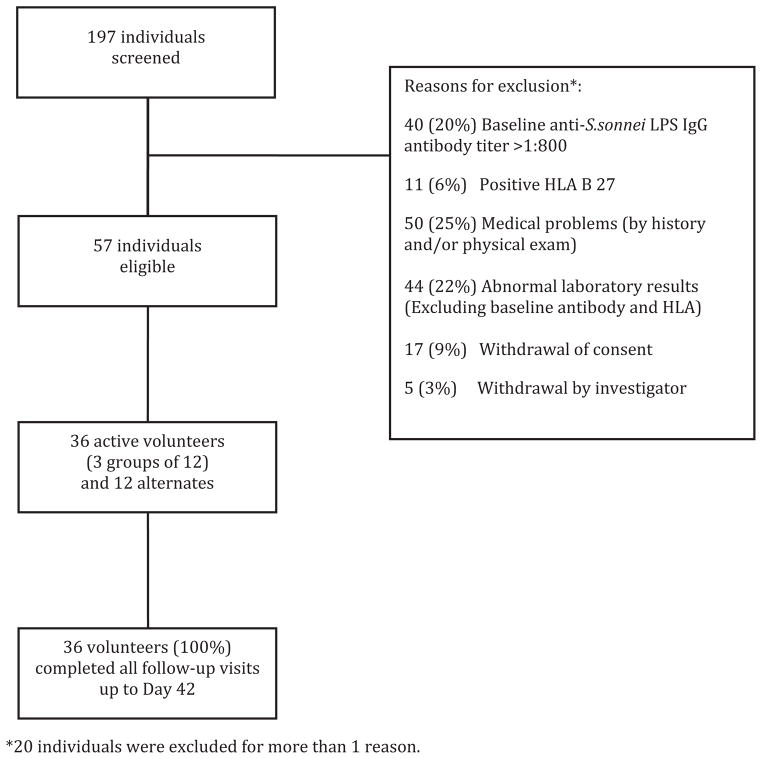

Subject screening, exclusion and enrollment are shown in Fig. 1. The actual post-inoculum counts of S. sonnei 53G were 93, 440 and 1680 CFU for Groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The percentages of form I (smooth-edged) and form II (rough-edged) colonies were 68% and 32% and 85% and 15% for Groups 2 and 3, respectively. No statistical differences in mean age, gender, education, or median baseline IgG antibody titers were observed among the three cohorts (Table 1). All enrolled subjects were followed up to completion.

Fig. 1.

Volunteer screening and enrollment.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline IgG antibody data.

| Group 1 (n = 12) | Group 2 (n = 12) | Group 3 (n = 12) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mean age (SD) | 23.8 (2.7) | 26.6 (3.2) | 24.1 (4.7) | 0.15a |

| 2. Number (%) of female | 5 (42) | 4 (33) | 4 (33) | 1.00b |

| 3. Number (%) of subjects with a vocational education or bachelor’s degree | 8 (67) | 8 (67) | 8 (67) | 1.00b |

| 4. Median anti-S. sonnei LPS IgG antibody titer at baseline | 1:100 | 1:200 | 1:100 | 0.34b |

Test for equivalence of means by ANOVA.

Fisher’s exact test.

Six subjects in Group 1 passed at least one dysenteric stool (Table 2). Among these, three subjects had dysentery accompanied by fever. In Group 2, 5 subjects suffered from dysentery, and one subject had diarrhea and fever. In Group 3, 9 subjects had dysentery, one of whom also had diarrhea and three of whom had concurrent fever. One of these 9 subjects met the criteria for shigellosis by having dysentery, fever, severe tenesmus, and shed S. sonnei. There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups in terms of frequency and severity of clinical diseases. Subjects who met any defined clinical disease endpoint were 6/12 (50%), 6/12 (50%) and 9/12 (75%) in Groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes following S. sonnei 53G challenge.

| Group | N | Challenge inoculum (CFU) | No. (%)with diarrheaa | No. (%)with dysenteryb | No. (%)with feverc | No. (%) meeting Clinical Disease End Pointd | No. (%) meeting Shigellosis Criteriae | No. (%) with any Systemic or Abdominal Symptoms | No. (%) with Severe Intestinal Symptoms | No. (%) with shedding of S. sonneif |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 93 | 0 | 6 (50) | 3 (25) | 6 (50) | 0 | 10 (83) | 0 | 7 (58) |

| 2 | 12 | 440 | 1 (8) | 5 (41) | 1 (8) | 6 (50) | 0 | 11 (92) | 1 (8) | 9 (75) |

| 3 | 12 | 1680 | 1 (8) | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | 1 (8) | 12 (100) | 1 (8) | 11 (92) |

Diarrhea was defined as two or more grade 3, 4, or 5 stools within 48 h totaling ≥200 mL in volume or a single grade 3, 4, or 5 stool ≥300 mL in volume.

Dysentery was defined as a stool of grade 3, 4, or 5 with visible blood.

Fever was defined as oral temperature >38.0 °C.

Clinical disease endpoint was defined as diarrhea, dysentery, and/or fever.

Shigellosis was defined as diarrhea and/or dysentery accompanied by a fever of ≥38.3 °C, one or more severe intestinal symptoms, and shedding of S. sonnei.

Subjects were considered positive for shedding if they produced at least one stool positive by either culture or PCR or both.

The number (%) of subjects who produced at least one stool tested positive for S. sonnei by culture in Groups 1, 2, and 3 were 6 (50%), 8 (67%), and 11 (92%), respectively. The median and range of number of days of culture-positive stools of Groups 1, 2 and 3 were 1.5 days and 1–4 days; 2.5 days and 1–4 days; and 3 days and 1–6 days, respectively. S. sonnei was detected in at least one stool by PCR in 58%, 67%, and 92% of Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. An increasing proportion of subjects shed S. sonnei, and longer periods of shedding were observed with each subsequent challenge dose. Most (75–83%) of the subjects in all cohorts had positive occult blood tests in at least one stool.

A correlation of immunologic responses with shedding and/or the presence of clinical diseases is presented in Table 3. The largest proportions of subjects who had shedding, seroconverted and positive ASC responses were those in the highest challenge dose group. All 4 subjects in Group 1 with neither shedding nor clinical diseases lacked Shigella-specific immune responses. Seven, 9 and 11 subjects of Groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively, who excreted S. sonnei showed positive IgA ASC responses, regardless of clinical symptoms. In addition, all of these 27 subjects also had significant increases of serum IgG or IgA or both.

Table 3.

Correlation of shedding of S. sonnei, clinical disease, seroconversion and positive antibody secreting cell (ASC) responses in each challenge group.

| Shedding of S. sonnei in stoola | Clinical diseaseb | Number of subjects | Number with IgG seroconversionc | Number with IgA seroconversionc | Number with positive IgG ASC responsed | Number with positive IgA ASC responsed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | − | − | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| + | − | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| + | + | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| − | + | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 12 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Group 2 | − | − | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| + | − | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| + | + | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| − | + | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Subtotal | 12 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Group 3 | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| + | − | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| + | + | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | |

| − | + | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 12 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

Subjects were considered positive for shedding if they produced at least one stool positive by either culture or PCR or both.

Clinical disease was defined as dysentery, diarrhea, and/or fever.

Seroconversion was defined as a ≥4-fold increase of anti-S. sonnei LPS antibody titer at Day 14 and/or Day 28 compared to the Day 0 titer.

Positive responses were ASC counts on Day 7 and/or 9 greater than mean + 3 SD of ASC count on Day 0 or ≥10 ASC per 106 PBMC when the count on Day 0 is 0. Significant dose related trends were observed for frequency of positive IgA-ASC (P = 0.03) and IgG-ASC (P = 0.04) responses among the three challenge groups (Jonckheere-Terpstra test).

Most solicited symptoms experienced by subjects were graded as mild or moderate. Two subjects in Group 2 experienced severe abdominal pain or malaise, and one subject in Group 3 experienced severe tenesmus. At Day 14 visit, one subject in Group 1 and one in Group 3 experienced a single elevation of total bilirubin of 2.65 and 1.79 mg/dL, respectively, a serious adverse event classified as grade IV according to the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) guidelines. However, neither patient showed other associated signs and symptoms. By Day 28, the total bilirubin levels returned to normal without treatment. All subjects reported no abnormalities on Day 42 by telephone assessments.

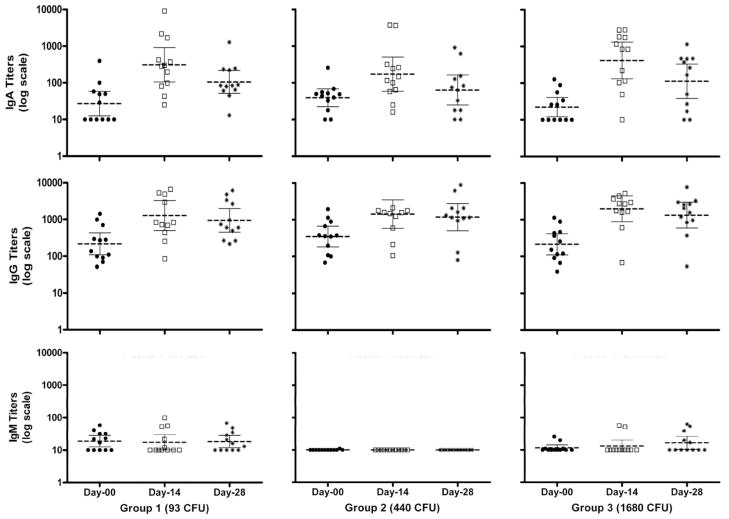

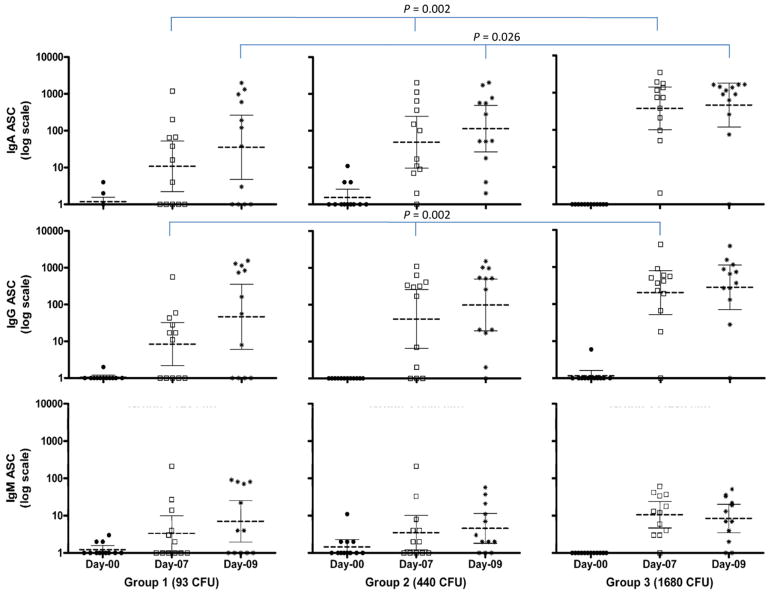

In all three cohorts, the geometric mean of serum IgA and IgG S. sonnei LPS titers elevated at Day 14 and dropped slightly at Day 28 (Fig. 2) and the cohort challenged with 1680 CFU had the greatest number of seroconversions (Table 3). None of the subjects had post-challenge serum IgM seroconversion. IgA and IgG ASC counts showed an increase at Day 7 and slightly increased further in Day 9 in all 3 cohorts. Dose related ASC responses were also observed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Serum IgA, IgG, and IgM antibody titers (bars represent geometric mean (middle bar) with 95% confidence intervals) against S. sonnei lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of subjects at baseline (closed round symbol), Day 14 (open square symbols) and Day 28 (star symbols) after challenge with S. sonnei 53G at doses of 93, 440 and 1680 colony forming unit (CFU). No significant dose related linear trends were noted.

Fig. 3.

IgA, IgG and IgM antibody secreting cells (ASC) counts (bars represent geometric mean (middle bar) with 95% confidence intervals) to S. sonnei lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of subjects at baseline (closed round symbol), Day 7 (open square symbols) and Day 9 (star symbols) after challenge with S. sonnei 53G at doses of 93, 440 and 1680 colony forming unit (CFU). ASCs were determined by ELISPOT. Significant dose related linear trends P values (linear by linear association) are shown.

4. Discussion

This study is the first S. sonnei human challenge model conducted in a Shigella endemic area. Similar studies have been conducted in North America to establish a challenge model or to evaluate vaccine efficacy [9–11,18]. Six of 11 volunteers (55%) developed clinical shigellosis after challenge with 500 CFU of S. sonnei 53G in skim milk buffer [11]. An inoculum of 400 CFU of S. sonnei 53G in a bicarbonate buffer was used in a re-challenge phase of a bivalent Shigella sonnei vaccine efficacy study and an attack rate of 67% (8/12) was observed in immunologically naïve subjects [10]. Another efficacy study using a challenge dose of 400 CFU in skim milk buffer reported a 55% (5/9) attack rate [9]. It was not clear why a challenge dose that elicited relatively low attack rates was selected for vaccine efficacy evaluation in these trials. Reported attack rates were higher and more consistent in studies that used bicarbonate rather than skim milk buffer [9,13,19,20]. Differences in inoculum preparation, buffer, clinical outcomes and small sample sizes limit our ability to compare results of these studies. In this study, we found that a dose of 1680 CFU of freshly harvested S. sonnei 53G administered after sodium bicarbonate buffer was necessary for 75% of healthy Thai adults to develop clinical diseases. This dose is higher than what was previously used in immunologically naïve volunteers and may reflect greater difficulties with challenge of volunteers from endemic environments [9,11].

One of our major concerns was underlying immunity in an endemic population, which might affect the establishment of a reliable human challenge model. Prior studies suggested that baseline serum antibodies may provide less severe symptoms [9,12,21], while other studies have reported no correlation with either disease outcome or infection [11,22,23]. Our exclusion criteria included having a baseline S. sonnei LPS IgG antibody titer of >1:800, which resulted in excluding 20% of screened subjects and enrollment of few subjects with borderline titers. We explored possible correlations between pre-existing antibody levels and infections or disease severity; however, no significant correlations were observed in any of these small cohorts.

Prior studies have attempted to correlate immune responses and protection; however, correlations are not yet clear [9,19,20]. If resistance to infection or disease is indeed immunologically correlated, the mediator might be local mucosal immune responses [11]. The IgA ASC assay is used as a marker for the activation of mucosal immune response [24,25]. We observed that IgA ASC results correlated better with colonization of S. sonnei than other immunologic assays as previously reported [10,11,25]. However, IgA ASC responses were the only evidence of immune responses in 2 subjects without detected shedding. Measurement of IgA ASC or other immune parameters should be continued until better correlates of immunity are discovered that may enable screening or characterization of non-naïve populations in future studies.

Despite the study limitations of small sample size, an inability to repeat the target dose, or test higher doses, the observed attack rate of 75% in Thai population is useful information for future vaccine efficacy testing in an endemic area. To ensure that populations with Shigella disease burden benefit from vaccination, vaccine efficacy testing should be conducted using populations where Shigella is endemic. This may ensure that safe and effective doses of vaccines are used in these populations, which might be quite different from doses used in more naïve populations. The current study establishing a human challenge model for Shigella related disease in an endemic population, is a step forward in the right direction.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the clinical staff at Mahidol University; Dr. Jittima Dhitavat, Dr. Wirach Maekananthawat, Dr. Varunee Desakorn, Ms. Supa Naksrisook; Mr. Apichai Srijan and the laboratory staff at the Department of Enteric Diseases, AFRIMS; the study coordinators, Ms. Narumon Thanthamnu and Ms. Umaporn Suksawad; and the Medical Monitors, Dr. Porntep Chantavanich and Dr. Chirasak Kamboonruang, for their significant contributions to the study. The authors also thank Dr. Edwin Oaks of Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) for providing S. sonnei LPS. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under IAA # Y1-AI-4906-03 and the Department of Defense, U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC).

Footnotes

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Army or Department of Defense.

Conflicts of interest: None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions: LB: Study design, acquisition, data analysis and manuscript preparation; PP: Study design, acquisition, data analysis and manuscript revision; SC: Study acquisition; KTC: Data analysis and manuscript preparation; DI: Study acquisition, data analysis and manuscript preparation; VB: Study acquisition; MMV: Study design and manuscript revision; TLH: Study design and manuscript revision; CJM: Study design, data analysis and final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors have approved the final version of this publication.

References

- 1.WHO. Diarrhoeal Diseases: Shigellosis. Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR) 2009 Feb; [cited; Available from: http://www.who.int/vaccineresearch/diseases/diarrhoeal/en/index6.html#disease]

- 2.Chompook P, Samosornsuk S, von Seidlein L, Jitsanguansuk S, Sirima N, Sudjai S, et al. Estimating the burden of shigellosis in Thailand: 36-month population-based surveillance study. Bull World Health Organ. 2005 Oct;83(10):739–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isenbarger DW, Hoge CW, Srijan A, Pitarangsi C, Vithayasai N, Bodhidatta L, et al. Comparative antibiotic resistance of diarrheal pathogens from Vietnam and Thailand, 1996–1999. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002 Feb;8(2):175–80. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo CY, Su LH, Perera J, Carlos C, Tan BH, Kumarasinghe G, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Shigella isolates in eight Asian countries, 2001–2004. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008 Apr;41(2):107–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill Gaston JS, Lillicrap MS. Arthritis associated with enteric infection. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003 Apr;17(2):219–39. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(02)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiller RC. Role of infection in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan;42(Suppl 17):41–7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosek M, Yori PP, Olortegui MP. Shigellosis update: advancing antibiotic resistance, investment empowered vaccine development, and green bananas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct;23(5):475–80. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833da204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kweon MN. Shigellosis: the current status of vaccine development. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun;21(3):313–8. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f88b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black RE, Levine MM, Clements ML, Losonsky G, Herrington D, Berman S, et al. Prevention of shigellosis by a Salmonella typhi–Shigella sonnei bivalent vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1987 Jun;155(6):1260–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrington DA, Van de Verg L, Formal SB, Hale TL, Tall BD, Cryz SJ, et al. Studies in volunteers to evaluate candidate Shigella vaccines: further experience with a bivalent Salmonella typhi–Shigella sonnei vaccine and protection conferred by previous Shigella sonnei disease. Vaccine. 1990 Aug;8(4):353–7. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz C, Baqar S, van de Verg L, Thupari J, Goldblum S, Olson JG, et al. Characteristics of Shigella sonnei infection of volunteers: signs, symptoms, immune responses, changes in selected cytokines and acute-phase substances. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995 Jul;53(1):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen D, Block C, Green MS, Lowell G, Ofek I. Immunoglobulin M, A, and G antibody response to lipopolysaccharide O antigen in symptomatic and asymptomatic Shigella infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1989 Jan;27(1):162–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.1.162-167.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Losonsky GA, Wasserman SS, Hale TL, Taylor D, et al. A modified Shigella volunteer challenge model in which the inoculum is administered with bicarbonate buffer: clinical experience and implications for Shigella infectivity. Vaccine. 1995 Nov;13(16):1488–94. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman AB, Venkatesan M. Construction of a stable attenuated Shigella sonnei DeltavirG vaccine strain WRSS1, and protective efficacy and immunogenicity in the guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model. Infect Immun. 1998 Sep;66(9):4572–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4572-4576.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orr N, Katz DE, Atsmon J, Radu P, Yavzori M, Halperin T, et al. Community-based safety, immunogenicity, and transmissibility study of the Shigella sonnei WRSS1 vaccine in Israeli volunteers. Infect Immun. 2005 Dec;73(12): 8027–32. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8027-8032.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnoy S, Baqar S, Kaminski RW, Collins T, Nemelka K, Hale TL, et al. Shigella sonnei vaccine candidates WRSs2 and WRSs3 are as immunogenic as WRSS1, a clinically tested vaccine candidate, in a primate model of infection. Vaccine. 2011 Aug;29(37):6371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen D, Orr N, Robin G, Slepon R, Ashkenazi S, Ashkenazi I, et al. Detection of antibodies to Shigella lipopolysaccharide in urine after natural Shigella infection or vaccination. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996 Jul;3(4):451–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.4.451-455.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coster TS, Hoge CW, VanDeVerg LL, Hartman AB, Oaks EV, Venkatesan M, et al. Vaccination against shigellosis with attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain SC602. Infect Immun. 1999 Jul;67(7):3437–43. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3437-3443.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotloff KL, Losonsky GA, Nataro JP, Wasserman SS, Hale TL, Taylor D, et al. Evaluation of the safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy in healthy adults of four doses of live oral hybrid Escherichia coli–Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain EcSf2a-2. Vaccine. 1995 Apr;13(5):495–502. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00011-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine MM, Woodward WE, Formal SB, Gemski P, DuPont HL, Hornick RB, et al. Studies with a new generation of oral attenuated shigella vaccine: Escherichia coli bearing surface antigens of Shigella flexneri. J Infect Dis. 1977 Oct;136(4):577–82. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen D, Green MS, Block C, Slepon R, Ofek I. Prospective study of the association between serum antibodies to lipopolysaccharide O antigen and the attack rate of shigellosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991 Feb;29(2):386–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.386-389.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuPont HL, Hornick RB, Dawkins AT, Snyder MJ, Formal SB. The response of man to virulent Shigella flexneri 2a. J Infect Dis. 1969 Mar;119(3):296–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/119.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DuPont HL, Hornick RB, Snyder MJ, Libonati JP, Formal SB, Gangarosa EJ. Immunity in shigellosis. II. Protection induced by oral live vaccine or primary infection. J Infect Dis. 1972 Jan;125(1):12–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orr N, Robin G, Lowell G, Cohen D. Presence of specific immunoglobulin A-secreting cells in peripheral blood after natural infection with Shigella sonnei. J Clin Microbiol. 1992 Aug;30(8):2165–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2165-2168.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van de Verg L, Herrington DA, Murphy JR, Wasserman SS, Formal SB, Levine MM. Specific immunoglobulin A-secreting cells in peripheral blood of humans following oral immunization with a bivalent Salmonella typhi-Shigella sonnei vaccine or infection by pathogenic S. sonnei. Infect Immun. 1990 Jun;58(6):2002–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.2002-2004.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]