Abstract

An ultrasensitive stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography/selected reaction monitoring/mass spectrometry (LC-SRM/MS) assay has been developed for serum estrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 4-methoxyestrone, and 2-methoxyestrone. The enhanced sensitivity was obtained by the use of Girard P (GP) pre-ionized derivatives coupled with microflow LC. The limit of detection for each estrogen using 0.5 mL of serum was 0.156 pg/mL and linear standard curves were obtained up to 20 pg/mL. Serum samples from 20 postmenopausal women (10 lifetime non-smokers and 10 current smokers) were analyzed using this new assay. Mean serum concentrations of estrone and 2-methoxyestrone were 14.06 pg/mL (± 1.56 pg/mL) and 3.30 pg/mL (± 1.00 pg/mL), respectively, for the 20 subjects enrolled in the study. The mean estrone concentration determined by our ultrasensitive and highly specific assay was significantly lower than that reported for the control groups in most previous breast cancer studies of postmenopausal women. In addition (and contrary to many reports) serum 16α-hydroxyestrone was not detected in any of the subjects, and 4-methoxyestrone was detected in only one of the subjects. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the mean serum concentrations of estrone and 2-methoxyestrone or the ratio of serum 2-methoxyestrone to estrone between the non-smoking and smoking groups. Interestingly, the one subject with measurable serum 4-methoxyestrone (2.3 pg/mL) had the lowest estrone and 2-methoxyestrone concentrations. Using this assay it will now be possible to obtain definitive information on the levels of serum estrone, 4-methoxyestrone, and 2-methoxyestrone in studies of cancer risk using small serum volumes available from previous epidemiology studies.

Keywords: estrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 4-methoxyestrone, 2-methoxyestrone, LC-MS, stable isotopes

INTRODUCTION

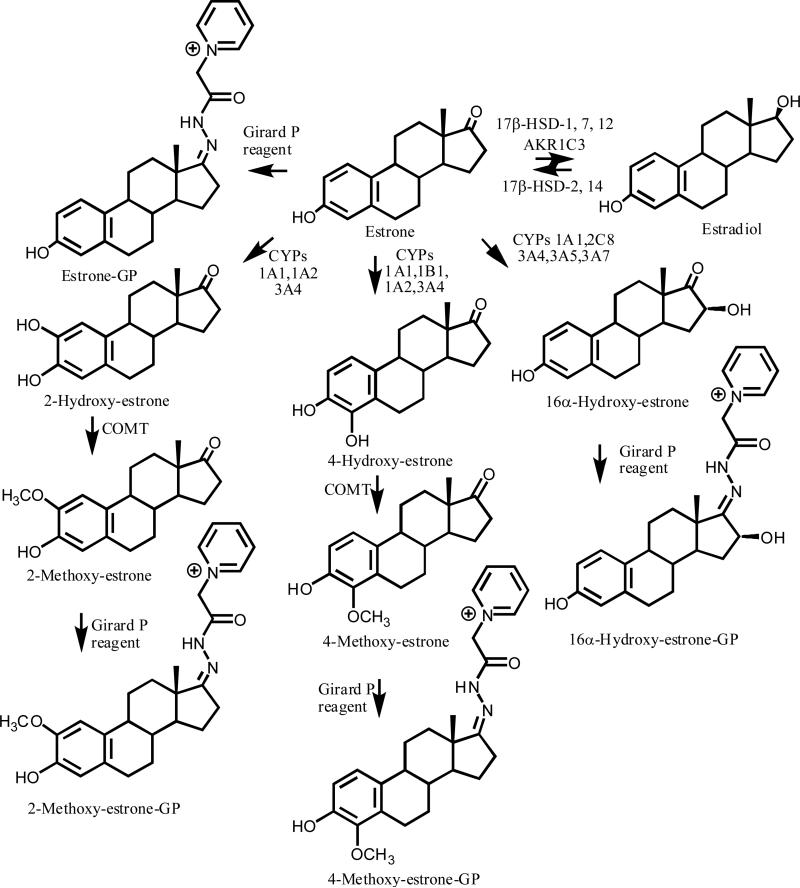

Breast cancer occurs primarily in postmenopausal rather than premenopausal women.1 This evidenced by the 90.3 % of new invasive breast cancers diagnoses and 93.1 % of 2009 breast cancer deaths in the USA, which were estimated to occur in women over the age of 45.2 Numerous reports have suggested that elevated 17β-estradiol (estradiol) and estrone levels are associated with an increase in breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women.3-5 This has been proposed to arise from a dual mechanism in which estradiol can act either as a hormone to stimulate aberrant cell proliferation or as a precursor to the formation of genotoxic catechol or hydroxylated metabolites.6-8 Estrogen biosynthesis, which occurs in the breast tissue of postmenopausal women, is fundamentally different from that which occurs in the ovaries of premenopausal women as it is dependent upon circulating C-19 androgen precursors. Aromatase (CYP19), which converts androstenedione to estrone and testosterone to estradiol, is expressed in the stromal and parenchymal components of breast cancer tissue.9 Moreover, estrone is also converted to estradiol in breast tissue by aldo-keto reductase (AKR1C3) together with 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD)-1, 7, and 12 (Figure 1), which could potentially cause a further increase in tissue estradiol concentrations10-13 In contrast, 17β-HSD-2, which is expressed in the normal epithelium of the breast, converts estradiol back to estrone using NAD+ as a co-factor, and can thus modulate the exposure of breast tissue to estradiol.12 The more recently discovered 17β-HSD-14 is also involved in NAD+-mediated conversion of estradiol to estrone and so it could also be involved in decreasing the exposure of breast tissue to estradiol.14

Figure 1.

Estrogen metabolism and formation of GP derivatives.

Estrone undergoes CYP1A1-, CYP1A2-, and CYP3A4-mediated oxidation to give the 2-hydroxyestrone and 4-hydroxyestrone catechol metabolites (Figure 1).15 In contrast, CYP1B1, metabolizes estrone to 4-hydroxyestrone with relatively high regioselectivity.16 4-Hydroxyestrone was reported to induce tumors in animal models, whereas 2-hydroxyestrone was inactive in the same models.17 Catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) converts 4-hydroxyestrone and 2-hydroxyestrone to the corresponding 4-, and 2-methoxy-metabolites (Figure 1),18 which can serve as indices of catechol estrogen formation.19 In addition, CYP3A4, CYP1A1, CYP2C8, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7 can convert estrone to 16α-hydroxyestrone (Figure 1).20-22 16α-Hydroxyestrone is thought to be a circulating metabolite6,23-27 that is involved in tumorigenesis.15,28 It has been proposed that a shift toward 2-hydroxyestrone away from the 16α-hydroxyestrone metabolic pathway, as indexed by the 2-hydroxyestrone to 16α-hydroxyestrone ratio, would be inversely associated with breast cancer risk.29 In fact, several recent epidemiological studies have reported that women with a high ratio of serum 2-hydroxyestrone metabolites to 16α-hydroxyestrone metabolites are at a decreased risk for breast cancer.30,31 This demonstrates the importance of accurately measuring the circulating concentrations of these un-conjugated estrogen metabolites, especially in postmenopausal women, as it could be helpful in identifying those women at risk of developing breast cancer.

Unfortunately, much of the current bioanalytical methodology employed for quantification of plasma and serum estrogens has proved problematic.32,33 The levels of estradiol and estrone in the serum and plasma of postmenopausal women were shown by LC-MS to be in the low pg/mL range.34-36 This has made reliable quantification of these two circulating estrogens extremely challenging. In fact, many of the reports, which have examined the relationship between circulating estradiol, estrone, and breast cancer risk, employed assays that did not have this level of sensitivity.3,4 Analysis of the estrone metabolites, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 2-methoxyestrone, and 4-methoxyestrone, in plasma and serum is even more challenging, calling into question many of the theories of breast cancer risk that are based upon the analysis of estrone and its circulating metabolites. In order to address these problems, we have developed and validated an ultrasensitive and highly specific stable isotope dilution LC-SRM/MS method for the quantification of estrone and three of its major metabolites. The assay, which is based on the use of pre-ionized GP derivatives, has been employed to establish the concentrations of estrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 4-methoxyestrone, and 2-methoxyestrone in the serum of non-smoking and smoking postmenopausal women.

EXPERIMENTAL

Clinical study

Twenty postmenopausal women were recruited for the study; 10 women were lifetime non-smokers and 10 were current smokers. The current smokers had smoked for 25-58 years (average 45 years) and smoked 0.1-1.5 packs of cigarettes/day (average 0.8 pack/day). None of the women smoked cigars. Menstrual and menopausal status was based on self report. All women were healthy and not taking exogenous hormones. The blood collection protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Review Board (Protocol # 800924). After the blood was collected, it was allowed to clot for 1 h at room temperature, serum was separated and aliquots were stored at −80 °C. Serum samples were allowed to thaw at room temperature and aliquots of 0.5 mL were used for the estrogen analyses.

Materials

Estrone, 2-methoxyestrone, 4-methoxyestrone, and 16α-hydroxyestrone were purchased from Steraloids Inc. (Newport, RI, USA). 13,14,15,16,17,18-[13C6]-Estrone, 13,14,15,16,17,18-[13C6]-2-methoxyestrone, and 13,14,15,16,17,18-[13C6]-4-methoxyestrone with an isotopic purity of 99% were purchased from Cambridge Isotope (Cambridge, MA, USA). Girard Reagent P [(1-Pyridinio) acetohydrazide chloride] was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., (Tokyo, Japan). Methyl-tertiary-butyl ether (MTBE), methanol, acetic acid, ammonium formate, formic acid, sodium chloride, hydrochloric acid and water were obtained from Sigma (Milwaukee, WI, USA). Double charcoal-stripped human serum was obtained from Golden West Biologicals, Inc (Temecula, CA, USA). Strata weak cation exchange (WCX) cartridges (55 μm, 70 Å, 100 mg) were obtained from Phenomenex Inc. (Torrance, CA, USA). High purity MS grade solvents were used for the assay. Estrone standard stock solutions were individually prepared in methanol at 1 mg/mL and stored at −20 °C. Calibration standard solutions were prepared by mixing equal amounts of the corresponding stock solutions and performing serial dilutions with methanol to the desired concentration. The internal standards (100 μg) were directly dissolved in 1 mL of methanol and stored at −80 °C.

Girard P derivatization of estrones

To a solution of estrones (1 ng of each) in seven different tubes in methanol (200 μL containing 10 % acetic acid), the GP reagent (10 μL from 1 mg/mL) was added and the derivatization reaction was performed at 37 °C. Formation of the estrone-GP derivatives was monitored after 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 and 120 min by LC-SRM/MS analysis. Analyses were conducted in duplicate.

Extraction and derivatization of serum estrogens

The internal standard solution containing 50 pg of each [13C6]-estrone standard in methanol (10 μL) was added to each serum sample (0.5 mL) using a calibrated syringe. The serum samples were acidified with 5 μL of 1 N HCl and 50 μL of saturated aqueous sodium chloride was added. The samples underwent liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) with 1.3 mL of MTBE by vortex-mixing for 10 min. They were then kept in ice for 20 min to allow separation of the two layers. The top organic layer was transferred to a fresh 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and dried in a Speed-Vac concentrator. The residue was dissolved in 200 μL of methanol containing 10 % acetic acid, GP reagent (10 μL) was added and the reaction mixture was allowed to stand for 15 min at 37 °C. The samples were evaporated to dryness using a Speed-Vac concentrator and re-dissolved in 500 μL of phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 6.8) before being purified on WCX solid phase extraction (SPE) columns. The columns were pre-conditioned with methanol (1 mL) followed by water (1 mL). The samples, re-dissolved in phosphate buffer, were loaded onto the columns, washed with 1 mL of ammonium formate buffer (20 mM, pH 5), water (1 mL), and methanol (1 mL). The estrone-GP derivatives were eluted with 1 mL of methanol/acetonitrile (20:80 v/v) containing 2 % formic acid. The eluent was evaporated to dryness using a Speed-Vac concentrator and the residue was dissolved in 50 μL of 20 % aqueous methanol and 10 μL was injected onto the LC-MS system.

LC-MS

A Vantage TSQ triple stage quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with a CaptiveSpray™ ion source (Michrom Bioresources Inc., Auburn, CA, USA) was used for the estrogen analyses. The mass spectrometer was interfaced with an Eksigent ultra-2D nanoflow LC system (Eksigent Technologies, Dublin, CA, USA) equipped with an autosampler and a thermo-controller (set at 4 °C). The syringe was washed with water (0.1 % formic acid) and acetonitrile (0.1 % formic acid) after every injection to avoid any potential carry-over. Separations were performed using a Magic C18AQ (0.3 × 150 mm, 3 μm, 200 Å) (Michrom Bioresources, Inc.) column at ambient temperature. Mobile phase A was water/acetonitrile (99.5:0.5 v/v) containing 0.1 % formic acid, and mobile phase B was acetonitrile/water (98:2 v/v) containing 0.1 % formic acid. Full loop injections of 10 μL were made using the metered injection mode. After injection, the sample was loaded onto the column using 3 min of isocratic mobile phase containing 5 % B. A linear gradient was then initiated at a flow rate of 5 μL/min as follows: 5 % B at 0 min, 5 % B at 2 min, 20 % B at 3 min, 20 % B at 4 min, 40 % B at 20 min, 40 % B at 21 min, 98 % B at 25 min, 5 % B at 26 min, 5 % B at 35 min. Operating conditions were as follows: spray voltage, 1100 V; ion transfer capillary temperature, 270 °C; collision gas, argon, S-lens voltage, 127 V; cycle time of 1 sec; and ion polarity positive. For the MS/MS scan, the pre-charged precursor ions (404.3, 410.3, 420.3, 434.3 and 440.3) were selected (unit mass resolution width) and the product ions were generated using collision induced dissociation (CID) with a collision energy of 31 eV and scanning of quadrupole-3 from m/z 50 to 500 with a cycle time of 1 sec. The SRM transitions were monitored at unit resolution in quadrupole-1 and quadrupole-3 with a dwell time of 140 millisec. They were selected based on the most intense product ion for each GP derivative as: estrone-GP (m/z 404 → m/z 157), [13C6]-estrone-GP (m/z 410 → m/z 157), 16α-hydroxyestrone-GP (m/z 420 → m/z 251), 4-methoxyestrone-GP (m/z 434 → 187), [13C6]-4-methoxyestrone-GP (m/z 440 → m/z 187), 2-methoxyestrone-GP (m/z 434 → m/z 187), and [13C6]-2-methoxyestrone-GP (m/z 440 → m/z 187).

Calibration curves

Calibration curves were made by adding standard estrones and [13C6]-estrogen internal standards to 0.5 mL of double charcoal-stripped human sera followed by extraction and derivatization as described above. Standard curves were plotted in the range 0.156 pg/mL to 20 pg/mL with the internal standard at 100 pg/mL. They were constructed by plotting the peak area ratios of the estrone to its relevant [13C6]-analog internal standard against the amount of estrone standard added to sera. [13C6]-estrone was used as the internal standard for 16α-hydroxyestrone.

Validation and stability

Quality control (QC) samples were prepared in double charcoal-stripped human serum at the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; 0.156 pg/mL), low quality control (LQC; 0.500 pg/mL), medium quality control (MQC; 2.50 pg/mL) and high quality control (HQC; 16.0 pg/mL) samples. The assay accuracy and precision were determined on 5 replicate serum samples on 3 different days. The stability of the GP derivatives was assessed by allowing validation samples to sit on the autosampler and re-analyzing them after 24 h. The stability of estrone and metabolites in the serum was also assessed following three freeze-thaw cycles (n=5) of QC samples.

Absolute recovery of estrones after extraction and derivatization

The recovery of each analyte was determined at the LQC, MQC, and HQC. One batch was analyzed after adding the internal standards (100 pg/mL) and followed the LLE as described above. In a second batch, the internal standards (100 pg/mL) were added after the LLE procedure. Both batches of samples were derivatized, purified and analyzed in consecutive LC-SRM/MS runs. The absolute recovery of estrones was calculated by comparing the ratios of analyte/internal standard of both batches.

Data Analysis

The serum estrone and metabolite concentrations were calculated using LCquan software (version 2.6) obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The statistical significance using a one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), standard deviations (SDs), and standard error of the means (SEMs) were determined using GraphPad Prism (v 5.01, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Reaction standardization of estrone and its metabolites with the GP reagent

Reaction of the GP reagent with estrone and its three metabolites (Figure 1) was essentially complete after 1 min. The derivatives were quite stable during the time-course of the reaction (120 min). For serum samples, a derivatization reaction time of 15 min was employed in order to ensure that reactions with the extracted estrogens had all gone to completion.

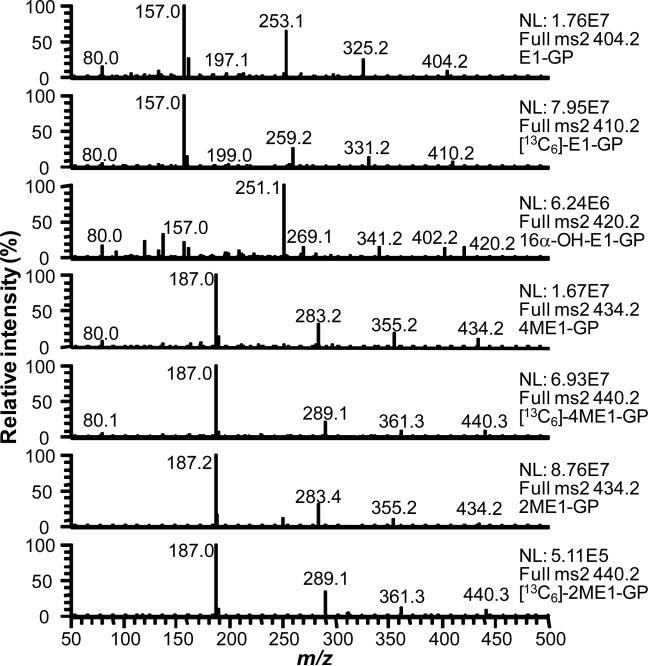

LC-MS/MS analysis of estrogen GP derivatives

Each of the estrogen derivatives exhibited intense ions corresponding to M+ of the relevant GP derivative (Figure 2). CID and MS/MS analysis revealed that five major product ions could arise from the derivatives (Fig. 3 (a-e)). A unique product ion was observed for 16α-hydroxyestrone at m/z 402, which corresponded to the expected loss of water from M+. The most intense product ions for estrone and the methoxyestrones corresponded to the structurally informative (d)-fragment, which contained the intact estrogen A- and B-rings. The [13C]-estrogen analogs and endogenous analytes had identical (d)-fragments because the [13C]-atoms located in the estrogen D-ring at C-13, C-14, C-15, C-16, C-17 and the C-18 methyl group, were lost during CID. The (d)-fragment was also observed for 16α-hydroxystrone at m/z 157; however, it was relatively weak. The most intense product ion from 16α-hydroxyestrone appeared at m/z 251 and corresponded to a dehydrated fragment-(b) (Figure 3). This ion contained the four intact steroid rings.

Figure 2.

Analysis of estrogen-GP derivatives by LC-MS/MS. The most intense product ions were selected for the SRM analysis

Figure 3.

Assignment of product ions from LC-MS/MS analysis of estrogen GP derivatives

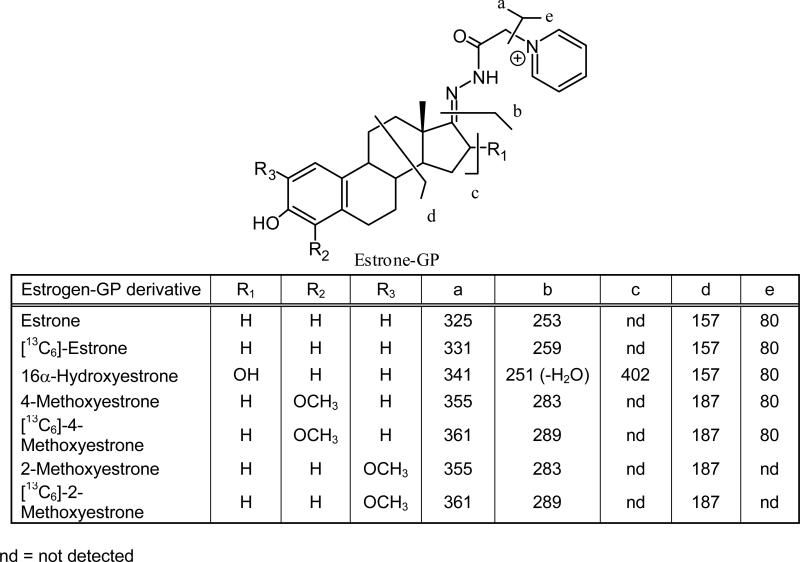

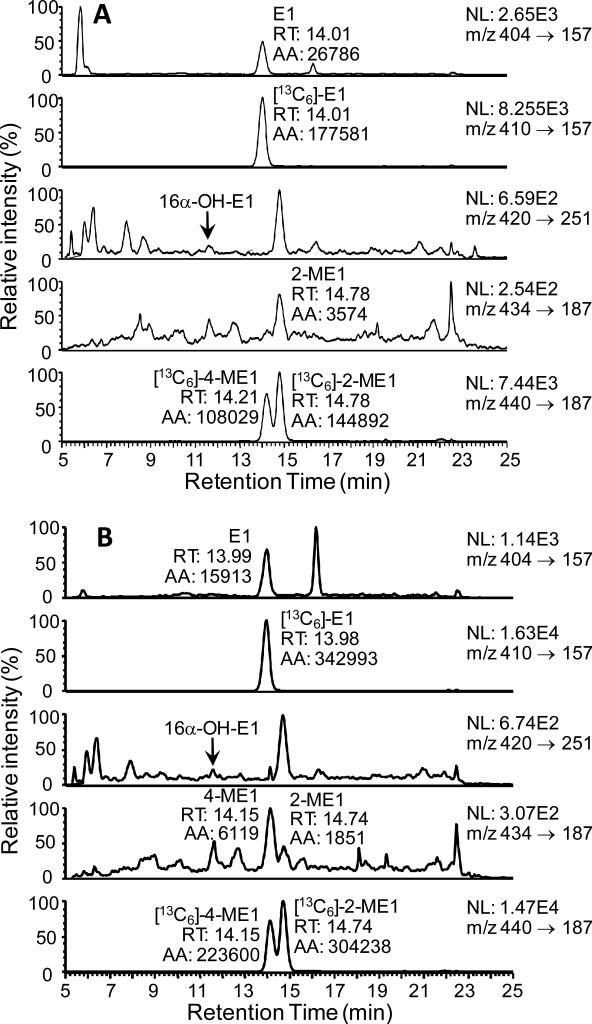

Method development

Double charcoal-stripped drug-free human serum was used to establish the analytical parameters required for the high sensitivity estrogen analysis. A two step sample preparation was employed, which involved one LLE using MTBE followed SPE of the GP-derivatives using a strata WCX column. Numerous solvents were tested for their ability to efficiently extract the estrogens including, ethyl acetate, ethyl acetate/hexane (3:2; v/v), dichloromethane, and MTBE. This revealed that MTBE was the most efficient of all those tested; furthermore, it removed many of the co-eluting interfering substances. Acidification of sera and addition of saturated brine also helped improve the recovery of estrone and its metabolites. There was an almost quantitative recovery of the estrogen-GP derivatives from the strata-WCX cartridge. Typical LC/SRM-MS chromatographic profiles of the four serum estrones as GP derivatives together with the three internal standards are shown for the LLOQ (0.156 pg/mL; Figure 4(A)) and HQC (16.0 pg/mL, Figure 4(B)). The four estrone derivatives were separated at a microflow LC rate (5 μL/min) within a 20 min chromatographic run time.

Figure 4.

LC-SRM/MS chromatograms for analysis of estrone and its metabolites extracted from double charcoal-stripped serum as GP derivatives. (A) LLOQ sample (0.156 pg/mL). (B) HQC sample (16.0 pg/mL). Abbreviations: E1, estrone, 16α-OH-E1, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 4-ME1, 4-methoxyestrone, 2-ME1, 2-methoxyestrone,.

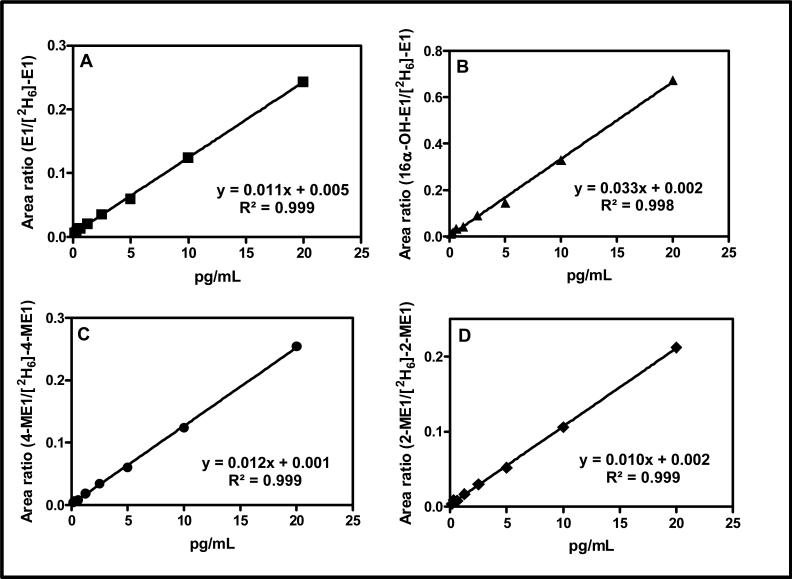

Calibration curve and limit of quantification

Calibration curves for quantifying each serum estrogen in this study were linear over a 100-fold concentration range with linear regression correlation coefficients ranging from 0.9977 to 0.9986 (Figure 5). Regression analysis of calibration curves constructed on 5 different days showed a mean (± SD) slope of 0.01284 (± 0.00142) for estrone-GP, 0.03078 (± 0.00499) for 16α-hydroxyestrone-GP, 0.01114 (± 0.00159) for 2-methoxyestrone, and 0.01342 (± 0.00152) for 4-methoxyestone. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), defined as the lowest serum standard that could be analyzed with an accuracy of 80 to 120 % and precision of ± 20 % for five replicates on three different days, was 0.156 pg/mL for each estrogen (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Typical standard curves and regression lines for four estrogens in the range 0.156 pg/mL to 20 pg/mL extracted from double charcoal-stripped serum and analyzed as GP derivatives. (A) E1. (B) 16α-OH-E1. (C). 4-ME1. (D) 2-ME1.

Table 1.

Inter-day variation for analysis of replicate QC samples (n=5) on three separate days.

| Parameter | Estrone | 16α-Hydroxyestrone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLOQ | LQC | MQC | HQC | LLOQ | LQC | MQC | HQC | |

| Theoretical (pg/mL) | 0.156 | 0.500 | 2.50 | 16.00 | 0.156 | 0.500 | 2.50 | 16.00 |

| Inter-day mean (pg/mL) | 0.149 | 0.506 | 2.58 | 15.97 | 0.140 | 0.483 | 2.60 | 14.12 |

| Precision (%) | 11.00 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 8.7 | 5.1 | 9.6 |

| Accuracy (%) | 95.4 | 101.2 | 103.4 | 96.4 | 89.6 | 96.5 | 104.1 | 88.3 |

| Parameter | 2-Methoxyestrone | 4-Methoxyestrone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLOQ | LQC | MQC | HQC | LLOQ | LQC | MQC | HQC | |

| Theoretical (pg/mL) | 0.156 | 0.500 | 2.50 | 16.00 | 0.156 | 0.500 | 2.50 | 16.00 |

| Inter-day mean (pg/mL) | 0.154 | 0.484 | 2.50 | 15.72 | 0.170 | 0.497 | 2.56 | 15.93 |

| Precision (%) | 11.4 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 3.4 | 4.1 |

| Accuracy (%) | 98.5 | 96.8 | 99.8 | 98.2 | 108.7 | 99.3 | 102.4 | 99.5 |

Assay accuracy, precision, recovery and stability

The absolute recovery of all four metabolites after extraction, derivatization, and purification from LQC, MQC, and HQC samples (n=3) was 81-90 % for estrone, 70-81 % for 16α-hydroxyestrone, 88-90 % for 2-methoxyestrone, and 87-93 % for 4-methoxyestrone. Overall, excellent accuracy and precision were obtained for the analysis of all three QC serum samples (Table 1). Intra-day accuracy (n=5) for the LQC (0.5 pg/mL), MQC (2.5 pg/mL), and HQC (16 pg/mL) ranged from 99 to 102 % for estrone, 89 to 112 % for 16α-hydroxyestrone, 99 to 110 % for 4-methoxyestrone, and 97 to 101 % for 2-methoxyestrone. The intra-day precision (n=5) ranged from 0.4 to 5.6 % for estrone, 0.9 to 9.6 % for 16α-hydroxyestrone, 2 to 7.8 % for 2-methoxyestrone, and 0.7 to 7.5 % for 4-methoxy-estrone (data not shown). The inter-day precision and accuracy data for the LQC, MQC, and HQC samples (n=5) on three separate days (Table 1) were quite similar to those observed in the individual intra-day validation. The precision and accuracy data for the analysis of the LQC, MQC, and HQC samples (n=5) after three freeze thaw cycles were similar to that shown in Table 1 for the inter-day validation (data not shown). The LLOQ, LQC, MQC, and HQC samples that were re-analyzed after 24 h standing on the autosampler gave essentially identical data to that obtained from the original analyses.

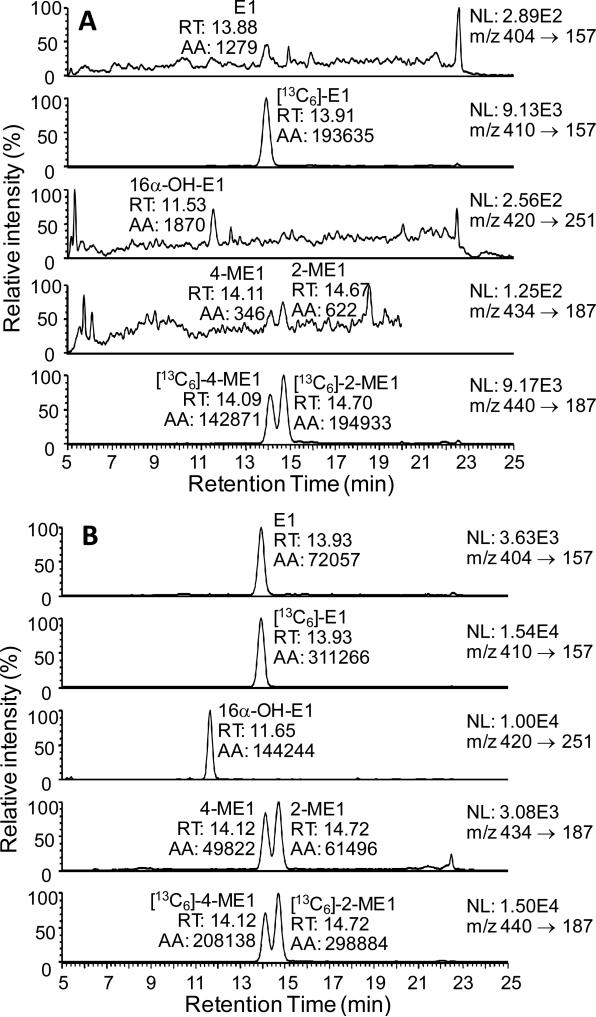

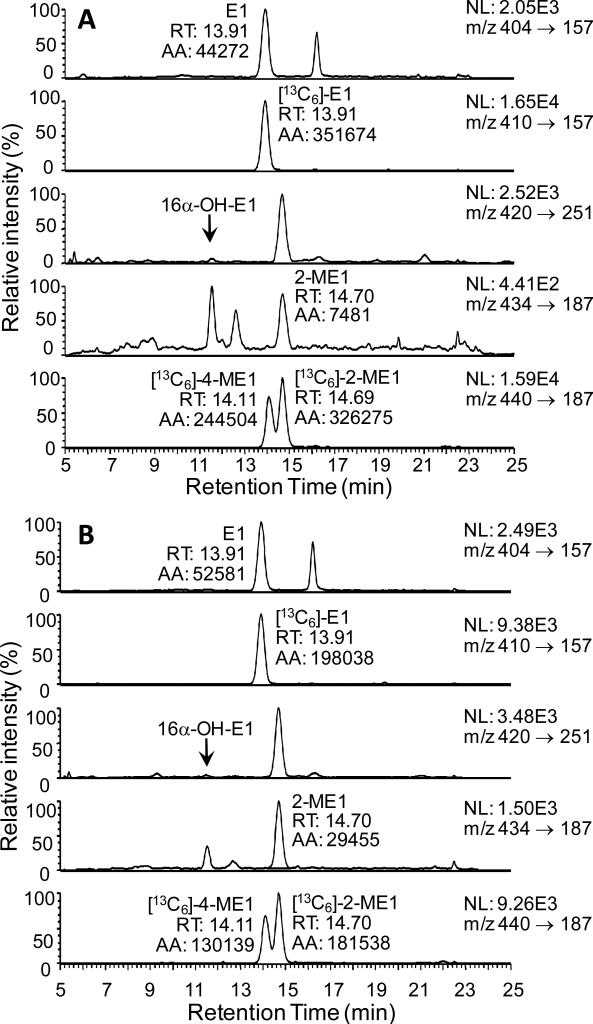

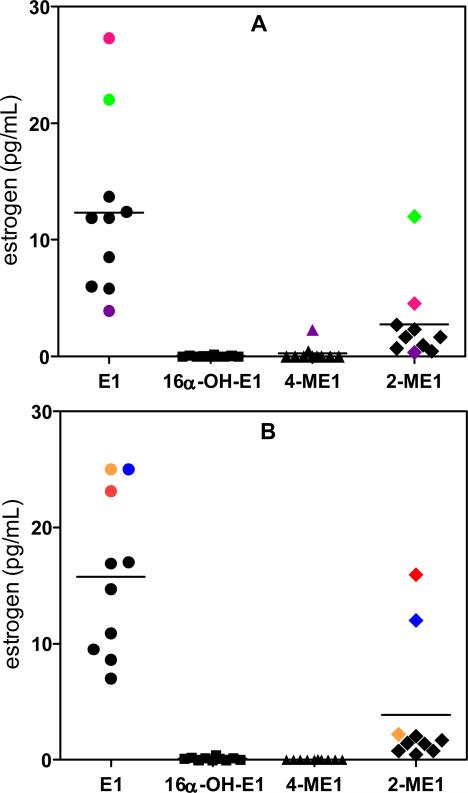

Analysis of estrones in the serum of postmenopausal women

Serum samples from twenty postmenopausal women (10 smokers and 10 non-smokers) were processed through the new validated LC-SRM/MS assay. The concentrations of estrone were above the concentration range of the standard curve (> 20 pg/mL) for some of the serum samples. Accurate concentrations were obtained by re-analysis of each sample (100 μL) after a ten-fold dilution with double charcoal-stripped serum. A LC-SRM/MS chromatogram of serum estrones for a typical non-smoker is shown in Figure 6(A). This revealed the lack of any 16α-hydroxyestrone or 4-methoxyestrone. One of the non-smokers did have measurable amounts of 4-methoxyestrone; however, 16α-hydroxyestrone was not detected (Figure 6(B)). A LC-SRM/MS chromatogram of serum estrones for one of the typical smoking women is shown in Figure 7(A). Again, 16α-hydroxyestrone and 4-methoxyestrone were not detected. The LC-SRM/MS chromatogram obtained from a woman smoker with elevated estrone and 2-methoxyestrone is shown in Figure 7(B). The mean concentration (± SEM) of estrone in the 10 non-smoking postmenopausal women was 12.34 pg/mL (± 2.33 pg/mL) and of 2-methoxyestrone was 2.74 pg/mL (± 1.11 pg/mL) (Figure 8(A)). The concentration of 16α-Hydroxyestrone was below the detection limit (0.156 pg/mL) in all subjects, whereas 4-methoxyestrone (at a level of 2.28 pg/mL) was detected in only one subject. (Figure 8(A)). The mean concentration of estrone in the 10 smoking postmenopausal women was 15.77 pg/mL (± 2.16 pg/mL) and of 2-methoxyestrone was 3.87 pg/mL (± 1.72 pg/mL) (Figure 8(B)). The concentrations of 16α-hydroxyestrone and 4-methoxyestrone were below the detection limit (0.156 pg/mL) in all subjects. The ratio of 2-methoxyestrone to estrone was 0.19 (± 0.05) in the non-smokers and 0.20 (± 0.07) in the non-smokers. There were no significant differences in serum estrone and 2-methoxyestrone concentrations between the smokers and non-smokers. The mean serum concentrations of estrone and 2-methoxyestrone were 14.06 pg/mL (± 1.56 pg/mL) and 3.30 pg/mL (± 1.00 pg/mL), respectively, for the 20 postmenopausal women in the study.

Figure 6.

LC-SRM/MS chromatograms for analysis of serum estrones as GP derivatives. (A) Typical non-smoker. (B) Non-smoker with elevated 4-ME1.

Figure 7.

LC-SRM/MS chromatograms for analysis of serum estrones as GP derivatives. (A) Typical smoker. (B) Smoker with elevated 2-ME1.

Figure 8.

Analysis of sera from postmenopausal women. (A) Non-smokers. (B) Smokers. Concentrations of estrone that were above the concentration range of the standard curve (mauve, red, green, blue, orange) were obtained after a ten-fold dilution of the samples (100 μL) with double charcoal-stripped serum. Symbols with the same colors (mauve, red, green, blue, orange, or purple) were from the same subject.

DISCUSSION

The availability of assays for serum estrone and its metabolites that combine high sensitivity with high specificity and reproducibility is essential for conducting sophisticated epidemiologic studies.37 There are three major bioanalytical methods used currently for such studies: immunoassay,38 gas chromatography-MS/MS,39 and LC-MS/MS.36 Radioimmunoassays and electrochemiluminescence immunoassays are by far the easiest to implement and the most widely used. However, they have not proven to be very successful in providing accurate concentrations of the low levels of circulating free estrone and its metabolites in postmenopausal women.40-43 Moreover, conjugated estrogens are present in plasma and serum at 2-3 orders of magnitude higher in concentration than the corresponding un-conjugated forms.44,45 Therefore, even if cross-reactivity is relatively low, conjugated estrogens can make a significant contribution to the antigen-antibody interaction and provide falsely elevated values. In addition, un-conjugated steroids such as estriol that are present in plasma can also lead to falsely elevated values.46

It is almost impossible to overcome the entire inherent assay problems involved in using immunoassay-based methodology, particularly for multiple estrogens. Therefore, reliable measurements of multiple estrogens in serum require the use of stable isotope dilution methodology in combination with LC-MS/MS or gas chromatography-MS/MS. These technologies represent the “gold standard” for the analysis of multiple estrogens when they are used under rigorously validated conditions.1,19 Losses during the extraction and chromatographic analysis are inherently taken into account by the use of an internal standard for each analyte.47 Stable isotope analogs can also act as carriers to prevent non-selective losses of trace analytes through binding to active surfaces during extraction and analyses.47

Gas chromatography-MS/MS when used in the electron ionization mode does not have the sensitivity for the analysis of estrogens in postmenopausal serum and plasma samples. In contrast, pentafluorobenzyl and trimethylsilyl derivatization of the 3- and 17-hydroxyl groups, respectively, coupled with electron capture negative chemical ionization MS/MS provides outstanding sensitivity with a LLOQ for serum estradiol of 0.6 pg/mL (2.3 pmol/L).39 However, elaboration of this methodology to multiple estrogens on a routine basis would be very challenging. LC-MS/MS methodology is not as challenging but endogenous estrogens are not effectively ionized using conventional electrospray ionization (ESI)- or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-based methodology. This has restricted the use of this conventional methodology to samples with higher concentrations of plasma and serum estrogens.43,48-50. In order to use ESI/MS or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/MS it has been necessary to enhance the ionization characteristics of estrogens by converting them to suitable derivatives.

The first approach to increasing ionization efficiency involved the preparation of electron-capturing pentafluorobenzyl derivatives coupled with the use of electron capture atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/MS.19,51 It is possible to quantify estrogens in the low pg/mL range in plasma using this approach.19 A second approach uses conventional derivatization coupled with LC-ESI/MS. This approach is exemplified by studies using the dansyl34,35,50, picolinoyl,52 or pyridinyl-3-sulfonyl53 derivatives. The third approach involves the preparation of pre-ionized (quaternized) derivatives, so that ionization is not required in the ESI source of the mass spectrometer. This approach is exemplified by studies in which N-methyl-2-pyridyl, 1-(2,4-dinitro-5-fluorphenyl)-4,4,-dimethylpiperazine, or N-methyl-nicotinyl groups were attached to the 3-hydroxy moiety of the relevant estrogen.54-56 The three derivatization strategies described above make it possible to quantify plasma and serum estrogens with limits of quantification in the low to sub-pg/mL (pmol/L) range.19,39,52,56,57

The ESI process, which occurs in solution, is followed by desolvation of resulting protonated molecules in the source of the mass spectrometer. Therefore, it is difficult to achieve complete ionization of all analyte molecules. This contrasts with pre-ionized derivatives, which are already completely ionized in solution as exemplified in a number of studies using neutral steroids.58-62 The N-methyl-nicotinyl pre-ionized derivative has proven to be particularly useful for the high sensitivity analysis of plasma and serum estrogens.56 We have now developed a similar approach using the GP derivative, which has been employed previously to analyze keto steroids.58,60,62,63 Even higher sensitivity can be obtained with the pre-ionized estrone GP derivatives when employed in combination with microflow LC-SRM/MS. This has made it possible to develop a method that can quantify estrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 4-methoxyestrone, and 2-methxyestrone simultaneously, with detection limits of 0.156 pg/mL for all four analytes (Figure 5).

Using this new assay we found that there were no significant differences in the mean serum concentrations of estrone and 2-methoxyestrone or the ratio of Figure 8). Therefore, when estrone concentrations were high, the 2-methoxyestone concentrations for the same individual were also high (Figure 8). Intriguingly, the one subject with measurable 4-methoxyestrone (non-smoker) had the lowest estrone and 2-methoxyestrone concentrations Figure 8(A)). Previous studies of postmenopausal women have shown that serum estrone is elevated in the breast cancer cases compared with in control subjects4,5,64-71 (Table 2). However, the mean estrone concentrations that were found in most of these studies for the control group were significantly higher than found with our new assay (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported concentrations of serum estrone in breast cancer cases and controls.

| Study | Cases (#) | Controls (#) | Cases (pmol/L) | Cases (pg/mL) | Controls (pmol/L) | Controls (pg/mL) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rancho Bernardo, US | 31 | 287 | 114.6 | 31.0 | 107.3 | 29.0 | Garland et al. 199264 |

| Washington County, US | 29 | 58 | 144.2 | 39.0 | 140.5 | 38.0 | Helzlsouer et al. 199465 |

| NYU WHS, US | 129 | 247 | 52.7 | 14.3 | 41.0 | 11.1 | Toniolo et al. 199566 |

| Columbia, US | 71 | 138 | 127.5 | 34.5 | 119.8 | 32.4 | Dorgan et al. 199667 |

| Nurses’ Health Study, US | 155 | 310 | 114.6 | 31.0 | 103.6 | 28.0 | Hankinson et al. 199868 |

| SOF, US | 97 | 243 | 88.8 | 24.0 | 74.0 | 20.0 | Cauley et al. 199969 |

| Nurses’ Health Study, US | 262 | 624 | 96.2 | 26.0 | 85.1 | 23.0 | Missmer et al. 200470 |

| EPIC, Europe | 677 | 1309 | 157.9 | 42.7 | 144.9 | 39.2 | Kaaks et al. 20054 |

| Michigan. US | 179 | 152 | 100.6 | 27.2 | 86.5 | 23.4 | Adly et al. 200671 |

| Hawaii, US (all women) | 132 | 261 | 132.0 | 35.7 | 112.0 | 30.3 | Woolcott et al. 20105 |

| Hawaii, US (Japanese) | 72 | 142 | 128.0 | 34.6 | 108.0 | 29.2 | Woolcott et al. 20105 |

| Philadelphia, US | NA | 20 | NA | NA | 52.0 | 14.1 | Present study |

CONCLUSIONS

The development of a validated stable isotope dilution microflow LC-SRM/MS assay has made it possible for the first time to rigorously evaluate the concentrations of estrone, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 2-methoxyestrone, and 4-methoxyestrone in serum samples obtained from postmenopausal women. The LLOQ for each analyte was 0.156 pg/mL (0.577 pmol/L for estrone) (Table 1; Figure 4(A)) and standard curves were linear in the range 0.156 pg/ml to 20 pg/mL (74.0 pmol/L for estrone) (Figure 5). The assay was very robust and required only 0.5 mL of serum. The concentrations of estrone and 2-methoxyestrone were > 0.350 pg/mL in all subjects. Therefore, future studies can be conducted using only 0.2 mL of serum, which will help preserve precious samples obtained from epidemiology studies. One subject had detectable serum 4-methoxyestrone, which might be a reflection of increased estrogen 4-hydroxylation. Increased 4-hydroxylation could potentially result in increased DNA damage and increased susceptibility to breast cancer.72 Therefore, serum 4-methoxyestrone might be a useful biomarker for breast cancer cases. We were initially surprised that 16α-hydroxyestrone could not be detected in serum from any of the subjects because previous reports had suggested that it was present in significant amounts in both premenopausal6,23,24 and postmenopausal25-27 women. However, more recent studies conducted using LC-MS-based methodology, have shown that serum 16α-hydroxyestrone could only be detected after hydrolysis with β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase.34,73,74 Furthermore, in a recent study, 16α-hydroxyestrone was below the limit of quantification (8 pg/mL) in 26 % of subjects even after the hydrolysis of the serum with β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase.74 It will be important in the future to determine whether non-conjugated 16α-hydroxyestrone can be detected in serum from breast cancer cases using our new, more sensitive assay. Furthermore, the improved sensitivity of our assay will permit the quantification of 16α-hydroxyestrone in all the case and control subjects after hydrolysis of the serum with β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase.

The mean concentration of serum estrone of in the 20 control subjects was significantly lower than that found for control subjects in most studies of breast cancer (Table 2). Therefore, the results from these previous studies will need to be reassessed. A re-analysis of serum samples from these previous studies would also afford the opportunity to assess the potential utility of 4-methoxyestrone as a biomarker of increased breast cancer risk. One previous study found serum estrone concentrations in control subjects that were similar to those found in our study and they were higher in the breast cancer cases (Table 2).66 Therefore, there is a possibility that serum estrone measurements could still reflect increased activity of tissue aromatase.75 When the analysis of serum estrone is coupled with that of serum 16α-hydroxyestrone, 2-methoxyestrone, and 4-methoxyestrone using our ultrasensitive highly specific assay, we predict that new insights into the role of estrogens in breast cancer will be gained.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of NIH grants UO1ES16004, P50HL083799, and P30ES0130508.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blair IA. Steroids. 2010;75:297. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society Breast cancer facts and figures 2009-2010. 2009.

- 3.Key T, Appleby P, Barnes I, Reeves G. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002;94:606. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaaks R, Rinaldi S, Key TJ, Berrino F, Peeters PH, Biessy C, Dossus L, Lukanova A, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Allen NE, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, van Gils CH, Grobbee D, Boeing H, Lahmann PH, Nagel G, Chang-Claude J, Clavel-Chapelon F, Fournier A, Thiebaut A, Gonzalez CA, Quiros JR, Tormo MJ, Ardanaz E, Amiano P, Krogh V, Palli D, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Trichopoulou A, Kalapothaki V, Trichopoulos D, Ferrari P, Norat T, Saracci R, Riboli E. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2005;12:1071. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolcott CG, Shvetsov YB, Stanczyk FZ, Wilkens LR, White KK, Caberto C, Henderson BE, Le ML, Kolonel LN, Goodman MT. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2010;17:125. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arslan AA, Shore RE, Afanasyeva Y, Koenig KL, Toniolo P, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 2009;18:2273. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liehr JG. Endocr. Rev. 2000;21:40. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liehr JG. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2001;7:273. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miki Y, Suzuki T, Tazawa C, Yamaguchi Y, Kitada K, Honma S, Moriya T, Hirakawa H, Evans DB, Hayashi S, Ohuchi N, Sasano H. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3945. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penning TM, Jin Y, Steckelbroeck S, Lanisnik RT, Lewis M. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004;215:63. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adamski J, Jakob FJ. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2001;171:1. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansson A. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009;114:64. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breitling R, Krazeisen A, Moller G, Adamski J. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2001;171:199. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukacik P, Keller B, Bunkoczi G, Kavanagh KL, Lee WH, Adamski J, Oppermann U. Biochem. J. 2007;402:419. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchiya Y, Nakajima M, Yokoi T. Cancer Lett. 2005;227:115. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray GI, Melvin WT, Greenlee WF, Burke MD. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippert TH, Seeger H, Mueck AO. Steroids. 2000;65:357. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawling S, Roodi N, Mernaugh RL, Wang X, Parl FF. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penning TM, Lee SH, Jin Y, Gutierrez A, Blair IA. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;121:546. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z, Guengerich FP, Kaminsky LS. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:867. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee AJ, Cai MX, Thomas PE, Conney AH, Zhu BT. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3382. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nebert DW. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jernstrom H, Klug TL, Sepkovic DW, Bradlow HL, Narod SA. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:991. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradlow HL, Jernstrom H, Sepkovic DW, Klug TL, Narod SA. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2006;87:135. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, Danielson ME, Ljung BM, Bauer DC, Cummings SR, Kuller LH. Epidemiology. 2003;14:740. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000091607.77374.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, Tworoger SS, Hankinson SE. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowers M, McConnell D, Jannausch ML, Randolph JF, Brook R, Gold EB, Crawford S, Lasley B. Clin. Endocrinol. 2008;68:806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Telang NT, Suto A, Wong GY, Osborne MP, Bradlow HL. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1992;84:634. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradlow HL, Davis DL, Lin G, Sepkovic D, Tiwari R. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 7):147. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, Tworoger SS, Hankinson SE. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 2008;17:2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Im A, Vogel VG, Ahrendt G, Lloyd S, Ragin C, Garte S, Taioli E. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1532. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dowsett M, Folkerd E. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:1. doi: 10.1186/bcr960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanczyk FZ, Lee JS, Santen RJ. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 2007;16:1713. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Roman JM, Issaq HJ, Keefer LK, Veenstra TD, Ziegler RG. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:7813. doi: 10.1021/ac070494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushnir MM, Rockwood AL, Bergquist J, Varshavsky M, Roberts WL, Yue B, Bunker AM, Meikle AW. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008;129:530. doi: 10.1309/LC03BHQ5XJPJYEKG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kushnir MM, Rockwood AL, Roberts WL, Yue B, Bergquist J, Meikle AW. Clin. Biochem. 2011;44:77. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santen RJ, Lee JS, Wang S, Demers LM, Mauras N, Wang H, Singh R. Steroids. 2008;73:1318. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanczyk FZ, Cho MM, Endres DB, Morrison JL, Patel S, Paulson RJ. Steroids. 2003;68:1173. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santen RJ, Demers L, Ohorodnik S, Settlage J, Langecker P, Blanchett D, Goss PE, Wang S. Steroids. 2007;72:666. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McShane LM, Dorgan JF, Greenhut S, Damato JJ. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 1996;5:923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rinaldi S, Dechaud H, Toniolo P, Kaaks R. IARC Sci. Publ. 2002;156:323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JS, Ettinger B, Stanczyk FZ, Vittinghoff E, Hanes V, Cauley JA, Chandler W, Settlage J, Beattie MS, Folkerd E, Dowsett M, Grady D, Cummings SR. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:3791. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsing AW, Stanczyk FZ, Belanger A, Schroeder P, Chang L, Falk RT, Fears TR. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 2007;16:1004. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanway SJ, Purohit A, Reed MJ. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:2765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geisler J, Ekse D, Helle H, Duong NK, Lonning PE. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;109:90. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao Z, Swift TA, West CA, Rosano TG, Rej R. Clin. Chem. 2004;50:160. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.023325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciccimaro E, Blair IA. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:311. doi: 10.4155/bio.09.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ceglarek U, Kortz L, Leichtle A, Fiedler GM, Kratzsch J, Thiery J. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2009;401:114. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hosogi J, Tanaka H, Fujita K, Kuwabara T, Ikegawa S, Kobayashi N, Mano N, Goto J. J. Chromatogr. B. 2010;878:222. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tai SS, Welch MJ. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6359. doi: 10.1021/ac050837i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh G, Gutierrez A, Xu K, Blair IA. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:3007. doi: 10.1021/ac000374a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamashita K, Okuyama M, Watanabe Y, Honma S, Kobayashi S, Numazawa M. Steroids. 2007;72:819. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu L, Spink DC. Anal. Biochem. 2008;375:105. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin YH, Chen CY, Wang GS. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1973. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishio T, Higashi T, Funaishi A, Tanaka J, Shimada K. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007;44:786. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang WC, Regnier FE, Sliva D, Adamec J. J. Chromatogr. B. 2008;870:233. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu X, Veenstra TD, Fox SD, Roman JM, Issaq HJ, Falk R, Saavedra JE, Keefer LK, Ziegler RG. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6646. doi: 10.1021/ac050697c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffiths WJ, Liu S, Alvelius G, Sjovall J. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:924. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffiths WJ, Alvelius G, Liu S, Sjovall J. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;10:63. doi: 10.1255/ejms.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griffiths WJ, Wang Y, Alvelius G, Liu S, Bodin K, Sjovall J. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:341. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Higashi T, Shibayama Y, Shimada K. J. Chromatogr. B. 2007;846:195. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griffiths WJ, Wang Y, Karu K, Samuel E, McDonnell S, Hornshaw M, Shackleton C. Clin. Chem. 2008;54:1317. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.100644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khan MA, Wang Y, Heidelberger S, Alvelius G, Liu S, Sjovall J, Griffiths WJ. Steroids. 2006;71:42. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garland CF, Friedlander NJ, Barrett-Connor E, Khaw KT. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992;135:1220. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Helzlsouer KJ, Alberg AJ, Bush TL, Longcope C, Gordon GB, Comstock GW. Cancer Detect. Prev. 1994;18:79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toniolo PG, Levitz M, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Banerjee S, Koenig KL, Shore RE, Strax P, Pasternack BS. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995;87:190. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dorgan JF, Longcope C, Stephenson HE, Jr, Falk RT, Miller R, Franz C, Kahle L, Campbell WS, Tangrea JA, Schatzkin A. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 1996;5:533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Speizer FE. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1292. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.17.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cauley JA, Lucas FL, Kuller LH, Stone K, Browner W, Cummings SR. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;130:270. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4_part_1-199902160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Missmer SA, Eliassen AH, Barbieri RL, Hankinson SE. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1856. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adly L, Hill D, Sherman ME, Sturgeon SR, Fears T, Mies C, Ziegler RG, Hoover RN, Schairer C. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:2402. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yue W, Santen RJ, Wang JP, Li Y, Verderame MF, Bocchinfuso WP, Korach KS, Devanesan P, Todorovic R, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;86:477. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Masi CM, Hawkley LC, Xu X, Veenstra TD, Cacioppo JT. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009;22:1148. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patel S, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT, Masi CM. Nutrition. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.08.017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santen RJ, Brodie H, Simpson ER, Siiteri PK, Brodie A. Endocr. Rev. 2009;30:343. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]