Abstract

The purpose of the Kentucky Elder Oral Health Survey (KEOHS) was to assess the oral health status of Kentuckians 65 and older.

The KEOHS consisted of a self-administered questionnaire and a clinical examination. Recruitment occurred from May 2002 through March 2005 of persons aged 65 and older (n=1386) whose functional ability was classified by residential setting. Independent elders living in their own homes were designated as “well-elders,” those who lived in skilled nursing facilities and who were functionally dependent were designated as “nursing home elders,” and those older adults who were considered frail were designated as “homebound elders.”

Significant associations were found between the functional ability of the elders and demographic characteristics. While elders who were homebound reported the highest rate of barriers to care, dental insurance, affordability, and transportation were consistently reported as barriers for all groups of elders.

This study has established the baseline oral health status of older adults in Kentucky and the data shows-differences that exist for various community living situations.

Keywords: Living Situation, Access to Care, Elders, survey, oral health, Kentucky

Introduction

The 2000 report released by the Surgeon General, Oral Health in America1 alerted Americans about the importance of oral health to their overall health and well being. In addition, it highlighted the fact that vulnerable populations experience more oral diseases and receive less care1. This can be seen in populations of older adults, as poor oral health increases with diseases which can occur with increasing age. Oral and pharyngeal cancers are diagnosed primarily among people over the age of 652. Periodontal disease and loss of teeth are more common among older adults. Studies3–5 suggest that older adults are less likely to visit a dentist than younger populations. Obtaining adequate oral health care is particularly problematic for older Americans who reside in a long-term care (nursing home) facilities6–8.

In 2006, Kentucky ranked second in the percentage of people who were edentulous over age 65, while its neighboring state of West Virginia ranked first9. Edentulism and poor oral health of seniors in Kentucky is a growing concern as evidence suggests that chronic diseases can be exacerbated or greatly influenced by oral health10–13.

The Kentucky Elder Oral Health Survey (KEOHS) assessed the oral health status of Kentuckians aged 65 and older and represented the first oral health assessment of elders in Kentucky. The study is unique in that it examined elders based on their functional ability via their living situation. Screening procedures followed two similar statewide surveys done to examine the oral health status of Kentucky children (under age 18) 14 and adults (age 18 and older) 15. The results from this study provide valuable information regarding the overall status of oral health for dentate and edentulous elders by age, gender, race, marital status, education, income, smoking status, and residence. Additionally, the results provide a context for which oral health professionals, state agencies, and other interested parties can develop strategic plans for improving the oral health needs of elders in their communities.

Methods

The KEOHS represents the third oral health survey meant to assess the oral health status of citizens of Kentucky, with particular focus on adults age 65 and older; the first two surveys assessed the oral health status of children14 and adults15.

The aims of the KEOHS were:

- Assessment

- Assess the oral health status and treatment needs of elders living in different types of residential settings

- Assess the perceived oral health status of Kentucky elders

- Assess the clinical oral health status

- Comparison

- Compare both perceived and clinical oral health status of Kentucky’s elders by geographic region and residential setting

- Develop a comparison to the 2002 Kentucky Adult Oral Health Survey (KAOHS)

- Surveillance

- Identify factors affecting dental access for Kentucky elders

- Provide information for a point-in-time comparison to the Healthy Kentuckians 2010 objectives

- Begin a starting point for an ongoing surveillance system of elder Kentuckians regarding their oral health status

In order to address the aims of the KEOHS, a two component evaluation was conducted: a self-administered questionnaire and a clinical examination. For participants who were unable to complete a written questionnaire, interviews were conducted in place of the self-administered survey. The self-administered questionnaire included questions in five general categories: demographics, general health, oral health, use of dental health services and health access beliefs. Demographic information included age, gender, race, marital status, education, location of residence, and income. Current smoking status, arthritis, cardiovascular risk factors, number of prescriptions, and mobility assessment were collected as part of the general health section. Oral health variables included questions on their general oral health, pain, bleeding gums, caries experience, and loss of teeth. Utilization of dental health services was assessed with questions regarding length of time since last dental visit and reasons for seeing the dentist. Barriers to dental care and suggestions for access to dental services were also collected with health access beliefs. Included in the questions regarding barriers to care, participants were asked to select the services that were difficult to obtain from the following: basic list (check-ups, cleanings and fillings), advanced list (crowns, bridges, implants, periodontal treatments and extractions), emergency list (able to make appointment and visit dentist right away for dental pain or oral problem), prosthodontic services (having dentures or partial dentures made by dentist), and other. Additionally, data was collected on the various residential settings of elders and were classified based on their community living status: nursing home (NH), homebound (HB), and well-elders (WE). Well-elders were defined as elders that utilized a senior center and were neither institutionalized nor confined to their home. A subset of the well-elders were recruited from the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging and designated as Sanders-Brown (SB) elders. The Sanders-Brown Center conducts research to improve the lives of older individuals by investigating the causes, treatment and cures of dementing neurodegenerative diseases and stroke. The elders participating from Sanders-Brown did not utilize Senior Centers and represent a cohort considered to have attained a higher socioeconomic and educational status than other participants.

The clinical examinations, included full mouth assessments and were performed to determine the reliability of self report responses regarding oral health status. Clinical examinationss were carried out by twelve dentists who were informed of the study through brochures distributed at local dental society meetings, the Kentucky Dental Association (KDA) newsletter, and by word of mouth. The dentists were members of the Kentucky Dental Association, voluntarily participated in six training sessions over a three-month period. All participating dentists attended a 3 hour training/calibration session. The assessment of dental caries and periodontal indicators were all dichotomous (yes/no) responses. Six anterior mandibular teeth (22 – 27) were used as indicator teeth for the periodontal markers including: gingival signs (free or attached gingival or papillae on the facial surface of three or more mandibular teeth were moderately to severely red or blue; teeth showed significant deviations from normal contour or texture), recession, calculus, tooth mobility, and gingival bleeding. Gingival bleeding was assessed by flossing between two teeth Assessments of overall periodontal health, determined by the number of negative responses to the periodontal markers, and urgency of periodontal problems were included for all dentate subjects. Urgency of periodontal problems was classified as “No problems detected,” “Routine care required,” “Early care required,” and “Immediate care required.” Other clinical examination assessments included extra-oral pathology (face and neck, tempomandibular joint, lips, corners of mouth) and intra-oral pathology (buccal and labial mucosa, roof of mouth, tongue, floor of mouth, and saliva (absent, no moisture, ropy, or thick) and denture evaluation for those who were edentulous including: hygiene, occlusion, integrity, stability, and retention as well as the health of the alveolar ridges, adequacy of replacements for missing teeth, and overall oral health. For the edentulous sample, the criteria for the denture assessment were dichotomous (adequate/inadequate).

With the exception of elders who were homebound, clinical examinations were carried out on all participants who completed the questionnaire. For elders who were homebound, it was not feasible to provide clinical examinations for each participant in his/her home, and so a sample of HB participants was selected. Pilot testing of the questionnaire and the clinical examination was conducted with 35 participants (15 WE, 10 NH, and 10 HB) chosen at random. Pilot testing and finalization of the questionnaire took place in the fall of 2001. The final survey consisted of 48 self-reported questions and 33 clinical items. Recruitment of statewide facilities to participate and training of dentists to assist in conducting the clinical examination were done from January through April 2002. Facilities were recruited via randomized phone calls with follow-up letters mailed to participating centers.

Based on the 2000 Census, 504,793 elders (65 and older) reside in Kentucky, comprising approximately 13% of Kentucky’s total population and 16.6% of Kentucky’s population over age 18. Most of these elders (n = 475,527) are non-institutionalized and of the non-institutionalized, 8,066 were designated as homebound by the state Administration on Aging (AOA) in 2002. To ensure a statewide sampling, five geographic regions (Western, Eastern, Bluegrass/Central, Northern, and Louisville) of the state previously identified in the children and adult surveys were utilized in the sampling scheme for the KEOHS (Table 1). A subset of 70 well-elders was recruited from the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging. These elders were designated Sanders-Brown (SB) elders in the KEOHS and due to their differences in socioeconomic and educational status the data reflects these findings separately from the WE group. A total of 1,386 elders completed the questionnaire (413 NH, 473 HB, 430 WE, and 70 SB), and 951 of these elders had clinical examinations (413 NH, 38 HB, 430 WE, and 70 SB).

Table 1.

Statewide Distribution of Sample

| Nursing Home | Homebound | Well-Elders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Population N (%) |

Sample N (%) |

Population N (%) |

Sample N (%) |

Population N (%) |

Sample N (%) |

| Kentucky | 29,266 | 413 | 8,066 | 473 | 475,527* | 430 |

| Western | 8,932 (30.5) |

120 (29.1) | 2,086 (25.9) |

167 (35.3) | 95 (22.1) | |

| Louisville | 5,936 (20.3) |

74 (17.9) | 673 ( 8.3) | 53 (11.2) | 86 (20.0) | |

| Bluegrass | 4,538 (15.5) |

68 (16.5) | 1,808 (22.4) |

75 (15.9) | 122 (28.4) | |

| Northern | 2,719 (9.3) | 59 (14.3) | 928 (11.5) | 44 (9.3) | 34 (7.9) | |

| Eastern | 7,141 (24.4) |

92 (22.3) | 2,571 (31.9) |

134 (28.3) | 93 (21.6) | |

Regional percentages are not provided for the Well-Elder population because Census Bureau does provide regional estimates without including the 8,066 homebound.

The first survey collection and clinical examinations took place in May 2002. The final surveys were completed in March 2005 and entered into an Excel database. Categorical data were summarized with counts and percentages. Chi-square tests were performed to evaluate association of elder groups with demographic, oral health, and dental service responses. All analyses, which focused on the self-report portion of the KEOHS and were performed with SAS v9.1 and a significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

Approval for this study was granted by the Medical Institutional Review Board, Office of Research Integrity, University of Kentucky (IRB@02-0182-FIV).

Results

The sample is described overall and by elder group in Table 2. Statistically significant associations were found between the elder group (WE, NH, HB) classification and all demographic characteristics. The majority of surveyed participants were between ages 65–84 (65.1%), however, well-elders (84.2% between 65 and 84 years of age) tended to be younger than nursing home elders (56.9% were 85 years or older). The sample was predominantly female (77.2%) and white (91.9%). Well-elders (77.9%) and nursing home elders (93.2%) tended to live in urban or small city residential locations, whereas home-bound elders were equally distributed across all residential locations. The majority of all elders were widowed (57.9%). Over half the surveyed participants (51.3%) had less than a high school education with home-bound elders being the least educated. A considerable number of all the elders (35.2%) did not know their annual household income, these predominately represented NH participants. Even so, nearly half (46.5%) of all the elders reported earning less than $15,000 per year. This group of low income elders was predominately comprised of the HB participants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Elder Groups

| Sanders- Brown (N = 70) |

Well- Elders (N = 430) |

Nursing Home (N =413) |

Homeboun d (N = 473) |

Total (N = 1386) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 65–84 | 65 | 362 (84.2%) | 178 (43.1%) | 293 (62.7%) | 898 (65.1%) |

| 85+ | 5 (7.1%) | 68 (15.8%) | 235 (56.9%) | 174 (37.3%) | 482 (34.9%) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 24 | 126 (29.3%) | 93 (22.5%) | 73 (15.4%) | 316 (22.8%) |

| Female | 46 | 304 (70.7%) | 320 (77.5%) | 400 (84.6%) | 1070 (77.2%) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 69 | 377 (88.7%) | 390 (94.7%) | 432 (91.3%) | 1268 (91.9%) |

| Black/Other | 1 (1.4%) | 58 (11.2%) | 22 (5.3%) | 41 (8.7%) | 112 (8.2%) |

| Residence* | |||||

| Urban | 70 | 176 (40.9%) | 247 (59.8%) | 174 (36.8%) | 667 (48.1%) |

| Small City | 0 (0.0%) | 159 (37.0%) | 138 (33.4%) | 151 (31.9%) | 448 (32.3%) |

| Rural | 0 (0.0%) | 94 (21.9%) | 23 (5.6%) | 148 (31.3%) | 265 (19.1%) |

| Marital Status* | |||||

| Never Married | 3 (4.3%) | 22 (5.1%) | 81 (19.9%) | 19 (4.0%) | 125 (9.1%) |

| Divorced/Separated | 5 (7.1%) | 56 (13.0%) | 32 (7.9%) | 63 (13.4%) | 156 (11.3%) |

| Widowed | 24 | 205 (47.7%) | 238 (58.5%) | 330 (70.2%) | 797 (57.9%) |

| Married | 38 | 147 (34.2%) | 51 (12.5%) | 58 (12.3%) | 294 (21.4%) |

| Education | |||||

| Less HS | 2 (2.9%) | 188 (44.8%) | 166 (43.3%) | 334 (70.8%) | 690 (51.3%) |

| HS/GED | 7 (10.0%) | 110 (26.2%) | 92 (24.0%) | 72 (15.3%) | 281 (20.9%) |

| Some College | 23 | 69 (16.4%) | 54 (14.1%) | 53 (11.2%) | 199 (14.8%) |

| College + | 38 | 53 (12.6%) | 71 (18.5%) | 13 (2.8%) | 175 (13.0%) |

| Income | |||||

| < $15,000 | 2 (2.9%) | 171 (39.8%) | 52 (12.6%) | 420 (88.8%) | 645 (46.5%) |

| $15,000 – $49,999 | 34 | 113 (26.3%) | 21 (5.1%) | 33 (7.0%) | 201 (14.5%) |

| $50,000+ | 29 | 16 (3.7%) | 6 (1.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 52 (3.8%) |

| Don't Know | 5 (7.1%) | 130 (30.2%) | 334 (80.9%) | 19 (4.0%) | 488 (35.2%) |

| Smoke Cigarettes | |||||

| No | 64 | 390 (92.2%) | 372 (91.4%) | 391 (83.4%) | 1217 (89.0%) |

| Yes | 4 (5.9%) | 33 (7.8%) | 35 (8.6%) | 78 (16.6%) | 150 (11.0%) |

| Dentate Status | |||||

| Dentate | 64 | 237 (56.4%) | 220 (55.0%) | 205 (43.3%) | 726 (53.3%) |

| Edentulous | 6 (8.6%) | 183 (43.6%) | 180 (45.0%) | 268 (56.7%) | 637 (46.7%) |

p < 0.05

Nearly half of all the elders self-reported they were edentulous (46.7%), and the rates ranged from a high of 56.7% in HB elders to a low of 8.6% in SB elders. Considerable agreement was found between the self-assessment of dentate status and the clinical assessment. Since only a small number of homebound elders had clinic examinations, dentate status was based on self-assessment. Comparisons between dentate and edentulous elders are shown in Table 3. The dentate status was significantly associated with age (p=0.003), location of residence (p<0.001), education level(p<0.001), income(p<0.001), smoking status(p<0.001), marital status (p<0.001), and elder group classification (p<0.001). Being younger, residing in urban areas, having more education, earning more, and not smoking were associated with retaining teeth.

Table 3.

Characteristics by Missing Teeth Classification

| Dentate (N = 726) |

Edentulous (N = 637) |

Total (N = 1363) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | |||

| 65–84 | 497 (68.7%) | 386 (60.9%) | 898 (65.1%) |

| 85+ | 226 (31.3%) | 248 (39.1%) | 482 (34.9%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 167 (23.0%) | 145 (22.8%) | 316 (22.8%) |

| Female | 559 (77.0%) | 492 (77.2%) | 1070 (77.2%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 668 (92.3%) | 583 (92.0%) | 1268 (91.9%) |

| Black/Other | 59 (7.8%) | 51 (8.0%) | 112 (8.2%) |

| Residence* | |||

| Urban | 393 (54.1%) | 258 (40.5%) | 667 (48.1%) |

| Small City | 232 (32.0%) | 211 (33.1%) | 448 (32.3%) |

| Rural | 99 (13.6%) | 164 (25.7%) | 265 (19.1%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Never Married | 71 (9.9%) | 49 (7.7%) | 125 (9.1%) |

| Divorced/Separated | 85 (11.8%) | 67 (10.6%) | 156 (11.3%) |

| Widowed | 375 (52.1%) | 413 (65.1%) | 797 (57.9%) |

| Married | 186 (25.8%) | 103 (16.2%) | 294 (21.4%) |

| Education* | |||

| Less HS | 282 (39.8%) | 400 (65.0%) | 690 (51.3%) |

| HS/GED | 148 (20.9%) | 130 (21.1%) | 281 (20.9%) |

| Some College | 140 (19.8%) | 55 (8.9%) | 199 (14.8%) |

| College + | 138 (19.5%) | 30 (4.9%) | 175 (13.0%) |

| Income* | |||

| < $15,000 | 266 (36.6%) | 373 (58.6%) | 645 (46.5%) |

| $15,000 – $49,999 | 143 (19.7%) | 55 (8.6%) | 201 (14.5%) |

| $50,000+ | 48 (6.6%) | 3 (0.5%) | 52 (3.8%) |

| Don't Know | 269 (37.1%) | 206 (32.3%) | 488 (35.2%) |

| Smoke Cigarettes* | |||

| No | 663 (92.7%) | 534 (84.8%) | 1217 (89.0%) |

| Yes | 52 (7.3%) | 96 (15.2%) | 150 (11.0%) |

| Elder Group* | |||

| Sanders-Brown | 64 (8.8%) | 6 (0.9%) | 70 (5.1%) |

| Well-Elders | 237 (32.6%) | 183 (28.7%) | 420 (30.8%) |

| Nursing Home | 220 (30.3%) | 180 (28.3%) | 400 (29.4%) |

| Homebound | 205 (28.2%) | 268 (42.1%) | 473 (34.7%) |

p < 0.05

Note: There were 23 elders with dentate status missing. Only elders with non-missing dentate status (n = 1363) are included in this table.

Approximately half of the dentate elders (372/726, 51.5%) reported having replacements for missing teeth. Of these elders, the majority (75.6%, n=266/352) reported that the replacements were adequate, where adequacy was assessed as being comfortable, functioning/working well, and looking good. Most (570/637, 89.5%) of the edentulous elders reported having dentures, but a lower percentage (59.3%) indicated that their dentures were adequate. A description of denture prevalence and adequacy is provided by elder group in Table 4. Overall, many (61.7%) of the elders have had their current set of dentures for more than a decade and approximately one-third of elders with dentures reported that the replacements were inadequate (failed to meet at least one of being comfortable, functioning/working well, or looking good) or needed new ones. The rate of inadequacy of replacements was significantly higher (p<0.05) in homebound elders (38.1%) than nursing home elders (20.6%) and well-elders (16.5%).

Table 4.

Denture Prevalence and Adequacy of Replacements

| Sanders- Brown N= 70 |

Well-Elders N= 430 |

Nursing Home N= 413 |

Homebound N= 473 |

Total N= 1386 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Dentures | 64 (91.4%) | 261 (60.7%) | 250 (60.5%) | 229 (48.4%) | 804 (58.0%) |

| Dentures | 6 (8.6%) | 169 (39.3%) | 163 (39.5%) | 244 (51.6%) | 582 (42.0%) |

| Adequate | 3 (50.0%) | 93 (56.7%) | 113 (69.8%) | 133 (54.3%) | 342 (59.3%) |

| Inadequate | 2 (33.3%) | 55 (33.5%) | 37 (22.8%) | 101 (41.2%) | 195 (33.8%) |

| Missing | 1 (16.7%) | 16 (9.8%) | 12 (7.4%) | 11 (4.5%) | 40 (6.9%) |

| Length of Dentures | n = 6 | n = 169 | n = 163 | n = 244 | n = 582 |

| 1–10 Years | 1 (16.7%) | 57 (33.7%) | 49 (30.1%) | 73 (29.9%) | 180 (30.9%) |

| 11+ Years | 5 (83.3%) | 102 (60.4%) | 89 (54.6%) | 163 (66.8%) | 359 (61.7%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (5.9%) | 25 (15.3%) | 8 (3.3%) | 43 (7.4%) |

| Need New Dentures | |||||

| Yes | 2 (33.3%) | 55 (32.5%) | 37 (22.7%) | 101 (41.4%) | 195 (33.5%) |

| No | 3 (50.0%) | 93 (55.0%) | 111 (68.1%) | 132 (54.1%) | 339 (58.2%) |

| Missing | 1 (16.7%) | 21 (12.4%) | 15 (9.2%) | 11 (4.5%) | 48 (8.3%) |

Note: Denture adequacy was self-reported and based on three criteria: Comfortable, function/work well, and look good, all of which must have been met

Regardless of having replacements or not, elders also reported dissatisfaction with the ability to chew (22.1%) and the appearance of their teeth and/or dentures (23.2%). Participants (19.3%) also reported having pain in the teeth, gums, or jaws and indicated current dental problems (27.7%). Even so, the majority (54.8%) of all participants reported their overall oral health status as excellent to good. The clinical assessment of overall oral health tended to have a higher percentage in the excellent to good rating when compared to the self-reported assessment of overall oral health for the Sanders-Brown (clinic: 92.9%, self: 85.3%) and well-elders (clinic: 66.5%, self: 60.0%), while for the homebound elders (clinic (n=38): 39.5%, self 40.8%) and those in nursing homes (clinic: 48.2%, self: 60.7%) tended to have higher excellent to good self-report percentages. This might explain why only 35.4% of elders reported having a dental visit within the past year. The range was a low of 22.8% (HB) and 28.3% (NH) to a high of 88.6% (SB).

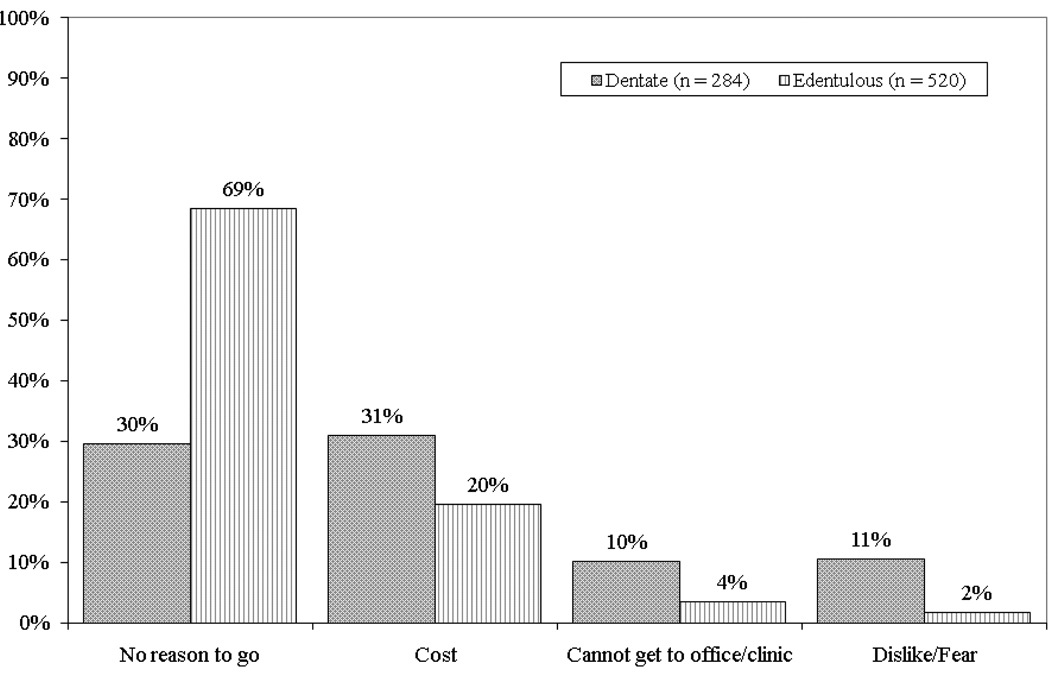

Homebound elders recorded the longest time without visiting a dentist, 45.3% had not seen a dentist in five or more years. Reasons for not visiting the dentists are shown in Figure 1. The most common response for not visiting the dentist in the past year was, “No reason to go”. Edentulous elders were twice as likely to report this as their main reason. Cost was also a common reason for not visiting a dentist in the past year, followed by an inability to get to a dental office. The surveyed elders’ top three reasons for their most recent dental visit were prosthetics care (39.2%), preventive work (30.0%), and pain or emergency treatment/extraction (15.0%).

Figure 1.

Reasons for not visiting the dentist within the past year (n = 804)

Overall, 40.6% (563/1386) of all elders reported that they had barriers to getting dental care and services. The specific barriers are presented in Table 5 by elder group. Homebound elders had the highest proportion reporting barriers to care (327/473) and cited no dental insurance (67.9%) and cost of dental care (63.3%) as barriers to receiving services. Dental insurance, affordability, and transportation were consistently reported as barriers across the elder groups, with HB and NH also indicating lack of mobility as an obstacle. Elders reported having difficulty obtaining basic (37.3%), advanced (41.6%), prosthodontic (34.1%), and emergency (14.9%) dental services. The top recommendations given by elders for improving access to dental care and services are also shown in Table 5. The support for these recommendations varied by elder group. While making dentistry more affordable was supported by all elder groups, nursing home and homebound elders were also interested in mobile clinic/mobile van access, home visits, and handicapped accessible dental offices.

Table 5.

Barriers and Recommendations

| Sanders- Brown |

Well-Elders | Nursing Home |

Homebound | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to Dental Services (n) | 8 | 112 | 116 | 327 | 563 |

| No Dental Insurance | 4 (50.05) | 50 (44.6%) | 42 (36.2%) | 222 (67.9%) | 318 (56.5%) |

| Can't Afford | 1 (12.5%) | 62 (55.4%) | 30 (25.9%) | 207 (63.3%) | 300 (53.3%) |

| No Transportation | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (8.0%) | 51 (44.0%) | 82 (25.1%) | 142 (25.2%) |

| Limited Mobility | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (33.6%) | 87 (26.6%) | 126 (22.4%) |

| Won't Accept Medicaid | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.7%) | 17 (14.7%) | 21 (6.4%) | 31 (7.3%) |

| Other/Don't Know | 4 (50.0%) | 8 (7.2%) | 12 (10.4%) | 21 (6.4%) | 45 (8.0%) |

| Recommendations (n) | 57 | 321 | 315 | 473 | 1166 |

| Make Dentistry Affordable | 27 (47.4%) | 197 (45.8%) | 106 (33.7%) | 317 (67.0%) | 647 (55.5%) |

| Mobile Clinic/ Mobile Van | 6 (10.5%) | 54 (12.6%) | 107 (34.0%) | 164 (34.7%) | 331 (28.4%) |

| House Visits | 2 (3.5%) | 8 (1.9%) | 73 (23.2%) | 176 (37.2%) | 259 (22.2%) |

| Handicap Accessible Offices | 5 (8.8%) | 18 (4.2%) | 55 (17.5%) | 99 (20.9%) | 177 (15.2%) |

| Other | 24 (42.1%) | 31 (7.2%) | 40 (12.7%) | 38 (8.0%) | 133 (11.4%) |

Discussion

Older adults constitute a growing proportion of the US population and as such increasingly demand the attention of dental health providers. Nonetheless, adults aged 65 years and older are not a homogenous group, complicating the universal provision of basic dental treatment to older adults. Additionally, limited public funding for dental care suggests that this funding could be targeted at elderly cohorts that report poor oral health outcomes.

The data presented in Table 2 and Table 3 highlight some of the important characteristics of the different elderly groups surveyed in this study. It also shows the dangers of attempting to survey older adults as one group without regard for living situation, education, functional status, socioeconomic considerations, and income. Elders from the SB and WE groups were more educated, earned more, and tended not to smoke in comparison to those from the HB and NH groups. Certain groups, such as the elders from SB and WE, had high dental care competency compared to those from the other elder groups, such as NH and HB. Older adults who were self-sustaining were more mobile and had better oral health outcomes. This suggests that instead of applying limited public funding allocated for the improvement of oral health to the general adult population aged 65 and older, these funds should target specific oral health needs within the context of each elder group.

Particular attention should be given to older adults classified as homebound. This group had the largest dental care disparities compared to any other group. These elders had higher levels of poor general and oral health outcomes. This group also contained the largest percentage of individuals who reported major barriers to getting dental care or services, had no dental insurance, and could not afford dental care. Evaluation of these groups of elders showed that oral health disparities of homebound elders was not solely a problem of age, as elders in the SB and WE groups had better oral health than the elders in the NH and HB groups regardless of age.

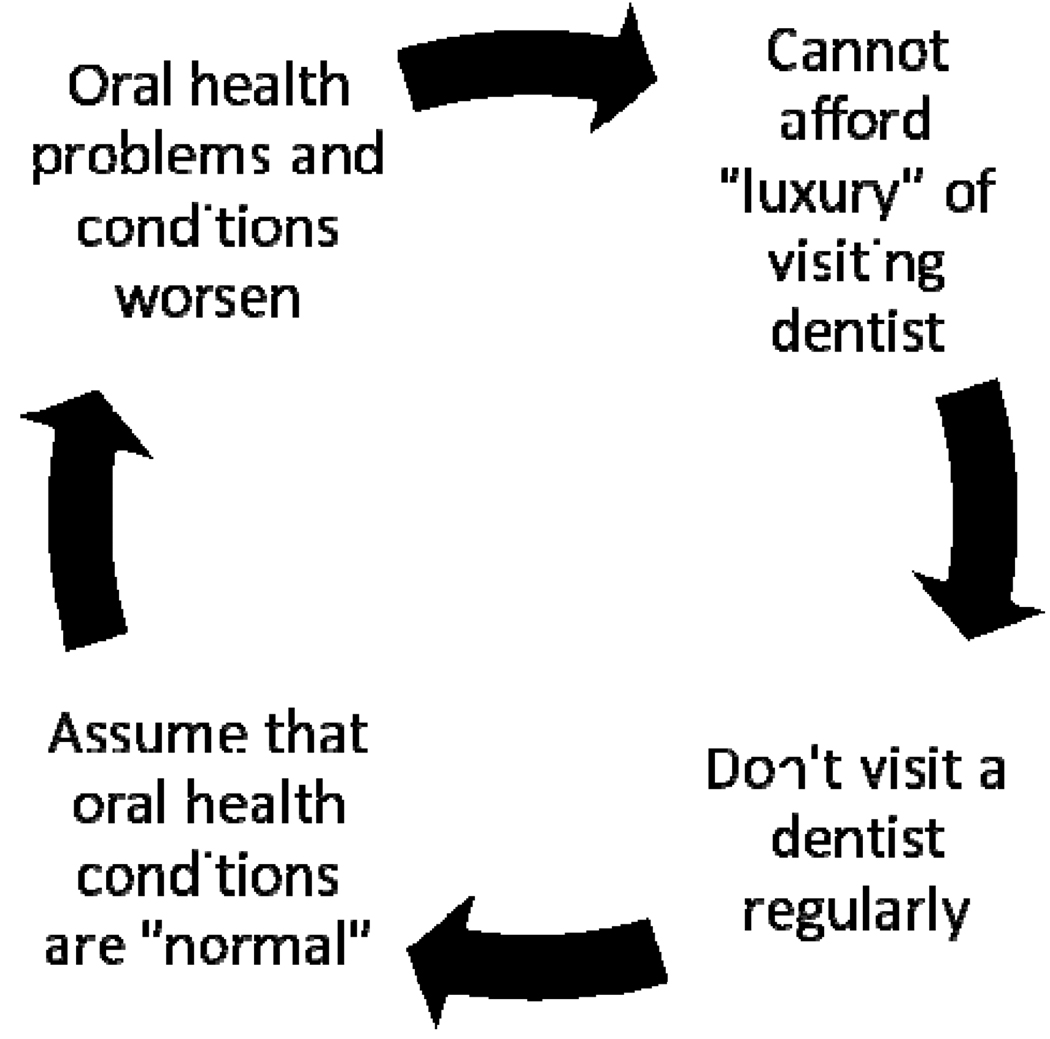

Although this is a cross sectional study, our findings suggest that elders without proper access to oral health services may become entrapped in a destructive oral health cycle we termed the Dental Death Spiral (Figure 2). The vast majority of elders surveyed indicated that they had not visited or were not visited by a dentist in the past year. Without a professional oral health assessment, these elders were unaware of oral health issues and allowed undetected and minor oral health problems to worsen. As restorative and emergency care is more costly than preventive care, elderly patients may spiral into a cycle that prevents them from adequately receiving proper oral health care. Clinical examination data from this study indicated that Kentucky elders may already be in the Dental Death Spiral as the majority of these older adults reported good to excellent overall oral health but clinical assessments did not agree with the their perception of their oral health. Elders living in NH and HB seem to be disproportionally affected by this cycle.

Figure 2.

Dental Death Spiral

A similar statewide study of oral health of older adults was conducted in Arizona16. Compared to individuals in the Arizona study, those in Kentucky were more likely to be edentulous (31% vs. 46.7%). In addition, elders in Arizona were more likely to have visited a dentist within the last year (46%) compared to those in Kentucky (35.4%). Findings from both studies found that participants who were homebound or living in nursing homes had the poorest oral health.

While the KEOHS provided the opportunity to investigate oral health conditions and attributes of Kentucky elders, this study was limited by the difficulties involved in the recruitment of older persons. Difficulties with recruitment at nursing homes resulted in a convenience sample rather than a randomized sample of approximately 10% of nursing homes in Kentucky. Similar recruitment problems existed for the well elders who utilized senior centers. In many cases, the elders considered the research team to be infringing on their time, on card playing, bingo games, and special events. Additionally, the logistical issues in carrying out clinical examinations on homebound elders limited the clinical comparisons of outcomes that could be made between other groups of elders and the homebound. It should also be noted that the length of time to complete the study (2002–2005) may have had some bearing on the results. The cross sectional nature of the study only allowed for one data point for subjects during the study period. It is impossible to say if the subjects would have given the same responses at other times during the four -year course of the study. In addition, four years have elapsed since completion of data collection. While we expect that results would be similar today, the oral health of older adults may have deteriorated. Given the current economic situation, elders may consider dental care to be more of a “luxury” now than ever before. Despite these difficulties, the study did have a sufficiently large sample to provide an even distribution of groups of participants for self-administered assessments and (the WE and NH) and for clinical examinations.

Conclusion

The general classification of individuals age 65 years and older as older adults is too broad a classification for a growing segment of the US population. Data from this study also indicated that the local and state government of Kentucky face numerous barriers to provide adequate and accessible dental care for older adults. Continual assessment of the oral health of older adults is required to target the at-risk populations.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support:

Kentucky Department of Public Health, Oral Health Program

Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, Thomas P. Rogers Endowment

University of Kentucky College of Dentistry

Department of Veterans Affairs

Kentucky Department of Health, Office of Aging Services

Contributor Information

Heather M. Bush, University of Kentucky, College of Public Health.

Noel E. Dickens, University of Kentucky, College of Public Health

Robert G. Henry, Dept of Veterans Affairs Office of Aging.

Lisa Durham, Western Kentucky University, Institute for Rural Health.

Nancy Sallee, University of Kentucky, College of Dentistry.

Judith Skelton, University of Kentucky, College of Dentistry.

Pam S. Stein, University of Kentucky, College of Medicine.

James C. Cecil, III, Oral Health Program, Commonwealth of Kentucky.

References

- 1.Oral health in America: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberg MA, Maloney WJ. Oral health and elder care. US Pharm. 2007;32:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamster IB. Oral Health care services for older adults: A looming crisis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:699–702. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burt BA, Eklund SA, Ismail AI. Dentistry, dental practice, and the community. Ontario, Canada: Saunders Book Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson PL, Andersen RM. Determinants of dental care utilization for diverse ethnic and age groups. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:254–262. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110020801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkey D, Berg R. Geriatric oral health issues in the United States. Int Dent J. 2001;51:254–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis AG. Geriatric dentistry in long-term-care facilities: current status and future implications. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:139–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1999.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strayer M. Oral health care for homebound and institutional elderly. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1999;27:703–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limeback H. The relationship between oral health and systemic infections among elderly residents of chronic care facilities: A review. Gerodontology. 1988;7:131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1988.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesäniemi YA, Syrjälä SL, et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779–781. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:559–569. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansson L, Lavstedt S, Frithiof L, Theobald H. Relationship between oral health and mortality in cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:762–768. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.280807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardison JD, Cecil JC, White JA, Manz M, Mullins MR, Ferretti GA. The 2001 Kentucky childrens oral health survey: findings for children ages 24 to 59 months and their caregivers. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis DO. Executive summary: 2002 Kentucky Adult Oral Health Survey. Department of Public Health. Commonwealth of Kentucky, Oral Health Program; 2003. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg RG, Berkey DB, Tang JM, Baine C, Altman DS. Oral health status of older adults in Arizona: Results from the Arizona Elder Study. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20:226–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2000.tb01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]