Abstract

Background

As worldwide life expectancy rises, the number of candidates for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer over 70 years will increase. This study aims to examine outcomes after esophagectomy in elderly patients.

Methods

Retrospective review of 474 patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer during 2002–2011. 334 (70.5%) patients were <70 years old (group A), 124 (26.2%) 70–79 years (group B) and 16 (3.4%) ≥80 years (group C). We analyzed the effect of age on outcome variables including overall and disease specific survival.

Results

Major morbidity was observed to occur in 115 (35.6%) patients of group A, 58 (47.9%) of group B and 10 (62.5%) of group C (p=0.010). Mortality, both 30- and 90-day was observed in 2(0.6%) and 7(2.2%) of group A, 4(3.2%) and 7 (6.1%) of group B, and 1(6.3%) and 2(14.3%) of group C, respectively (p=0.032 and p=0.013). Anastomotic leak was observed in 16(4.8%) patients of group A, 6(4.8%) of group B and 0(0%) of group C (p=0.685). Anastomotic stricture (defined by the need for ≥2 dilations) was observed in 76(22.8%) of group A, 13(10.5%) of group B and 1(6.3%) of group C (p=0.005). Five-year overall and disease specific survival was 64.8% and 72.4% for group A, 41.7% and 53.4% for group B, 49.2% and 49.2% for group C patients (p=0.0006), respectively.

Conclusions

Esophagectomy should be carefully considered in patients 70–79 years old and can be justified with low mortality. Outcomes in octogenarians are worse suggesting esophagectomy be considered on a case by case basis. Stricture rate is inversely associated to age.

Keywords: Esophagus, Esophageal cancer, Esophageal surgery, Outcomes, Statistics-regression analysis

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer is a disease that specially affects the elderly, showing a peak incidence after age 65. Moreover, recent population based literature has reported that patients harboring Barrett’s metaplasia over 70 years old have an increased incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma [1,2] compared to ages 30–69. Esophageal cancer in the elderly often occurs in patients with significant comorbidities contributing to the complexity of a treatment strategy. As worldwide actuarial life expectancy increases, the number of candidates for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer over 70 years will progressively increase. In an outcomes analysis of 2315 patients derived from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Database who underwent esophagectomy, 30% of patients were ≥ 70 years old, and 5% were > 80 years old.[3]

Controversy around the candidacy of elderly patients to tolerate esophagectomy remains primarily in two forms: whether age by itself is an independent risk factor for complications and death, and whether there is a survival benefit from esophagectomy in the elderly. Several single institution series have reported greater rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality in the elderly age group when compared to their younger counterparts [4–9], while others have reported similar outcomes [10–14]. This study aims to examine short and long outcomes after esophagectomy for cancer in elderly patients (≥70 years old) when compared to younger patients. Our hypothesis is that age by itself may not be an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study population includes consecutive patients undergoing esophagectomy with curative intent for malignant disease on the Thoracic Surgery service at the Massachusetts General Hospital between January 1, 2002 and January 1, 2011. This retrospective study was inclusive of a wide spectrum of surgical techniques for esophagectomy. Technique was mainly determined by tumor location and surgeon preference. Minimally invasive esophagectomy was always performed with laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach and thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus with an intrathoracic stapled anastomosis. The study specifically includes patients with an esophagogastric anastomosis; therefore, patients undergoing esophageal reconstruction by means of jejunal or colonic conduit were excluded. Additional exclusions include those patients undergoing additional procedures such as laryngectomy or pharyngectomy. Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy were included. Demographics, preoperative and intraoperative data as well as outcome measures were recorded. The Institutional Review Board specifically considered this retrospective chart review, including subject selection and confidentiality, and waived the need for patient consent.

Upper endoscopy was performed on all patients whereupon a diagnosis of esophageal cancer was confirmed. All patients were evaluated with computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Most patients underwent staging with positron emission tomography and endoscopic ultrasound if feasible. Pulmonary function tests were routinely obtained and cardiac stress testing if risk factors were present. Patients with resectable T3N0 or greater disease were considered for concurrent neoadjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin/5-Flourouracil) plus 5000 cGy of intensity modulated radiation. Young patients (<70 years) with T2N0 disease were also considered for neoadjuvant therapy. A minority of patients underwent induction chemotherapy alone followed by surgery.

Esophageal reconstruction consisted of creation of a gastric tube using a linear stapling device (Autosuture; Covidien, Norwalk, CT) along the lesser curve. The diameter of the gastric conduit and the location of the gastric anastomosis on the conduit were variable. Esophagogastric anastomoses were performed using either a manual two-layer technique modified from the original description by Sweet [15], or employing an end-to-end anastomotic circular stapling device (Autosuture 25, 28, 31 mm; Covidien). Stapled esophagogastric anastomoses were performed in the thorax only. The use of a pyloric drainage procedure was surgeon dependent. Pyloromyotomy with an omental buttress was the most common pyloric drainage procedure performed. Almost all patients received a feeding jejunostomy.

Long-term follow up data was obtained from different sources. The Social Security Death Index (SSDI) was consulted to determine the vital status of the patients and primary care physicians were contacted to determine the cause of death.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoints for this study are overall morbidity, in-hospital or 30 and 90-day mortality, overall (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). Data from the patients was analyzed using the statistical software Stata/SE 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of categorical variables between age groups. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare medians among age groups. We analyzed the effects of age on major morbidity, anastomotic outcomes, operative mortality and long-term survival. Major morbidity was defined as a composite outcome including all variables listed in Table 3. Odds ratios were calculated for major morbidity, anastomotic outcomes and mortality taking subjects <70 years as reference. Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the effect of age as a continuous variable on the primary end points while adjusting for variables of interest. Both OS and CSS analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, log-rank test and the Cox proportional hazards method. Statistical significance was considered with a p value less than 0.05.

Table 3.

Postoperative complications in patients undergoing esophagectomy

| Variable | <70 years (n=334) | 70–79 yr (n=124) | ≥80 years (n=16) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Complications, n (%) | 179(53.6) | 77(62.1) | 14(87.5) | 0.011 |

| Major complications, n (%) | 124(37.2) | 59(47.6) | 10(62.5) | 0.016 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 48(14.4) | 36(29.0) | 6(37.5) | <0.001 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 5(1.5) | 7(5.7) | 0(0) | 0.034 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1(0.3) | 1(0.8) | 0(0) | 0.732 |

| Respiratory failure | 10(3) | 11(8.9) | 3(18.8) | 0.002 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 0(0) | 2(1.6) | 1(6.3) | 0.002 |

| Ventilation >48hr | 6(1.8) | 5(4.0) | 1(6.3) | 0.252 |

| Pneumothorax | 54(16.2) | 16(12.9) | 2(12.5) | 0.657 |

| Pneumonia | 36(10.8) | 13(10.5) | 5(31.3) | 0.039 |

| Empyema | 1(0.3) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.811 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3(0.9) | 3(2.4) | 0(0) | 0.389 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 3(0.9) | 1(0.8) | 0(0) | 0.928 |

| Gastric outlet syndrome | 24(7.2) | 10(8.1) | 1(6.3) | 0.936 |

| Anastomotic leak | 16(4.8) | 6(4.8) | 0(0) | 0.685 |

| Ileus | 26(7.8) | 11(8.9) | 4(25) | 0.057 |

| Pyloric dilation | 23(7) | 14(11.4) | 2(12.5) | 0.263 |

| Sepsis | 9(2.7) | 7(5.7) | 0(0) | 0.224 |

| Cerebrovascular event | 0(0) | 1(0.8) | 0(0) | 0.243 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy | 5(1.5) | 1(0.8) | 0(0) | 0.757 |

| Acute renal injury | 3(0.9) | 4(3.2) | 0(0) | 0.164 |

| Chylothorax | 6(1.8) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.280 |

| Requiring ligation | 5(1.5) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.347 |

| Bleeding requiring reoperation | 1(0.3) | 2(1.6) | 0(0) | 0.274 |

| Need for postoperative transfusion | 57(17.1) | 35(28.2) | 3(18.8) | 0.030 |

RESULTS

Careful review of a prospective database revealed 474 consecutive patients who underwent esophageal resection with gastric conduit reconstruction over a 9-year period. Patients were divided into three groups based on age. Of these, 334 (70.5%) patients were <70 years old (group A), 124 (26.2%) 70–79 years old (group B) and 16 (3.4%) ≥80 years old (group C). Patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients undergoing esophagectomy.

| Variable | <70 years (n=334) | 70–79 years (n=124) | ≥80 years (n=16) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 57.9±7.4 | 73.8±2.9 | 82.2±1.6 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.093 | |||

| Male | 278(83.2) | 99(79.8) | 10(62.5) | |

| Female | 56(16.8) | 25(20.2) | 6(37.5) | |

| Comorbidities*, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 129(41.1) | 67(59.3) | 3(23.1) | 0.001 |

| CAD | 38(12.1) | 29(25.7) | 3(23.1) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 41(13) | 20(17.7) | 0(0) | 0.157 |

| PVD | 8(2.6) | 6(5.3) | 2(15.4) | 0.029 |

| CVA | 7(2.2) | 6(5.4) | 0(0) | 0.194 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6(1.8) | 4(3.2) | 1(6.3) | 0.379 |

| Steroid use | 5(1.6) | 2(1.8) | 0(0) | 0.890 |

| CHF | 1(0.3) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.818 |

| COPD | 4(1.2) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.528 |

| Pulmonary function tests | ||||

| FEV1 %, mean±SD | 86.9±20.2 | 86.2±18.2 | 86.6±21.2 | 0.962 |

| DLCO %, mean±SD | 85.0±22.9 | 83.7±20.6 | 83.5±18.9 | 0.897 |

| Histology | 0.947 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 261(78.1) | 100(80.7) | 14(87.5) | |

| Squamous | 43(12.9) | 15(12.1) | 2(12.5) | |

| HGD | 17(5.1) | 3(2.4) | 0(0) | |

| Other malignant | 13(3.9) | 6(4.8) | 0(0) | |

| Stage | 0.454 | |||

| 0 | 27(9.4) | 7(6.2) | 0(0) | |

| IA | 66(22.9) | 25(22.1) | 3(21.4) | |

| IB | 40(13.9) | 9(8.0) | 2(14.3) | |

| IIA | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| IIB | 77(26.7) | 29(25.7) | 5(35.7) | |

| IIIA | 61(21.2) | 34(30.1) | 4(28.6) | |

| IIIB | 9(3.1) | 8(7.1) | 0(0) | |

| IIIC | 3(1.0) | 1(0.9) | 0(0) | |

| IV | 5(1.7) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n(%) | 173(51.8) | 46 (37.1) | 3(18.8) | 0.001 |

CAD: Coronary Artery Disease, CHF: Congestive Heart Failure, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, CVA: Cerebrovascular Accident, DLCO: Carbon Monoxide Diffusing Capacity, FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second, PVD: Peripheral Vascular Disease

Comorbidities information available for 440 patients (<70 years: 314, 70–79 years: 113 and ≥80 years: 13).

Surgical technique

Ivor-Lewis was the most frequent approach to esophagectomy in our study population in 216 (45.7%) patients, followed by a left thoracoabdominal in 152 (32.1%), transhiatal in 49 (10.4%), minimally invasive in 38 (8.0%) and modified McKeown in 18 (3.8%) patients (Table 2). Based on this, 406 (85.6%) anastomoses were located in the chest while 68 (14.4%) were in the neck. The esophagogastric anastomosis was constructed with a hand-sewn technique in 385 (81.2%) cases and with a stapled technique in 89 (18.8%). Pyloromyotomy was performed in 174 (36.8%) patients; 118 (35.4%) patients in group A, 52 (41.9%) in group B, and 4 (25%) in group C (p=0.268). After the procedure, 444 (94.3%) patients were extubated in the operating room; this was achieved in 314 (94.9%) patients in group A, 116 (93.6%) in group B and 14 (87.5%) in group C (p=0.429).

Table 2.

Surgical procedures, techniques and parameters among patients undergoing esophagectomy.

| Variable | <70 years (n=334) | 70–79yr (n=124) | ≥80 years (n=16) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery, n (%) | ||||

| Ivor Lewis | 156(46.9) | 53(42.7) | 7(43.8) | 0.743 |

| Minimally invasive | 31(9.3) | 7(5.7) | 0(0) | 0.216 |

| Thoracoabdominal | 102(30.6) | 46(37.1) | 4(25) | 0.339 |

| Transhiatal | 31(9.3) | 14(11.3) | 4(25) | 0.120 |

| Modified McKeown | 13(3.9) | 4(3.2) | 1(6.3) | 0.826 |

| Anastomotic Location, n (%) | 0.123 | |||

| Cervical | 44(13.2) | 19(15.3) | 5(31.3) | |

| Intrathoracic | 290(86.8) | 105(84.7) | 11(68.8) | |

| Above/at azygos vein | 186(64.1) | 60(48.4) | 7(63.6) | |

| Below azygos vein | 104(35.9) | 45(36.3) | 4(36.4) | |

| Anastomotic technique, n (%) | 0.125 | |||

| Hand-sewn | 264(79.0) | 106(85.5) | 15(93.8) | |

| Stapled | 70(21.0)* | 18(14.5) | 1(6.2) | |

| Reinforcement of anastomosis, n (%) | 188(56.3) | 81(65.3) | 9(56.3) | 0.214 |

Includes 1 case with linear side-to-side anastomosis.

Postoperative care

Postoperatively, patients spent a median of 1 day in the intensive care unit (ICU) (interquartile range [IQR]:1–2 days, range:1–36 days); patients in group A spent a median of 1 day in the ICU (IQR:1–2 days, range:1–35 days), while patients in group B spent 1 day (IQR:1–2 days, range:1–36 days) and patients in group C spent 1.5 days (IQR: 1–2 days, range:1–8 days) (p=0.031). Patients were discharged from the hospital at a median of 10 days of hospital stay (IQR:9–13 days, range:6–64 days); patients in group A spent a median of 10 days (IQR:9–13 days, range:6–76 days), patients in group B spent 11 days (IQR:9–15 days, range:6–136 days) and patients in group C spent 11 days (IQR: 9.5–20 days, range:8–69 days) (p=0.004).

Postoperative morbidity

Major morbidity was observed to occur in 193 (40.9%) patients. The most frequent postoperative complications were atrial arrhythmias in 89 (18.9%), pneumothorax in 72 (15.3%), pneumonia in 54 (11.4%), delayed gastric emptying in 35 (7.4%) and respiratory failure in 24 (5.1%) patients. Major morbidity occurred in 124 (37.2%) patients of group A, 59 (47.6%) of group B and 10 (62.5%) of group C (p=0.016). The distribution of complications according to age groups can be observed in Table 3. There was a significant trend towards increased postoperative major morbidity with increasing age, as seen in Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that increasing age was significantly associated with major postoperative morbidity (OR=1.03 [1.01–1.05], p=0.014), while adjusting for gender, hypertension, CAD, PVD, diabetes, neoadjuvant therapy and surgical technique.

Table 4.

Effect measures for outcomes of interest in patients undergoing esophagectomy.

| Outcome | AGE GROUP OR/HR (95% CI) | p value for trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <70 years (n=334) | 70–79 years (n=124) | ≥80 years (n=16) | ||

| Anastomosis | ||||

| Stricture | 1.00 | 0.40 (0.21–0.75) | 0.23 (0.03–1.76) | 0.001 |

| Hand-sewn | 1.00 | 0.40 (0.21–0.77) | 0.21 (0.03–1.62) | 0.002 |

| Stapled | 1.00 | N/C | N/C | - |

| Major morbidity | 1.00 | 1.53 (1.01–2.33) | 3.37 (1.12–10.19) | 0.005 |

| Mortality | ||||

| 30-day | 1.00 | 5.53 (1.20–25.50) | 11.07 (1.54–79.34) | 0.008 |

| 90-day | 1.00 | 2.91 (1.04–8.14) | 7.50 (1.78–31.64) | 0.004 |

CI: Confidence Interval, HR: Hazard Ratio, N/C: Not computable, OR: Odds Ratio

Anastomotic outcomes

Anastomotic leak was observed in 16 (4.8%) patients of group A, 6 (4.8%) of group B and none (0%) of group C (p=0.685). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed no association between anastomotic leak and age (OR=0.99 [0.94–1.03], p=0.574) while adjusting for gender, hypertension, CAD, diabetes, neoadjuvant therapy, anastomotic technique and reinforcement of the anastomosis. Anastomotic stricture, defined as the need for 2 or more dilations after surgery, was observed in 76 (22.8%) patients of group A, 13 (10.5%) patients of group B and 1 (6.3%) patient of group C (p=0.005). There was a significant inverse relation between age and stricture rate (Table 4).

Perioperative Mortality

Thirty-day mortality was observed in 7 (1.5%) patients of the entire cohort, while 90-day mortality was seen to occur in 16 (3.6%) patients. Mortality at 30 days was observed in 2 (0.6%) patients of group A, 4 (3.2%) of group B, and one (6.3%) of group C (p=0.032). Mortality at 90 days was observed in 7 (2.2%) patients of group A, 7 (6.1%) of group B and 2 (14.3%) of group C (p=0.013). There was a significant trend towards increased 30-day and 90-day mortality with increasing age (Table 4). Multivariate analysis failed to reveal a significant association between age and 30-day mortality (OR=1.08 [0.97–1.21], p=0.165) while adjusting for gender, hypertension, CAD, neoadjuvant therapy, surgical technique and occurrence of major postoperative complications; however, it did show a significant association with mortality at 90 days (OR=1.08 [1.01–1.16], p=0.022) while adjusting for the same variables.

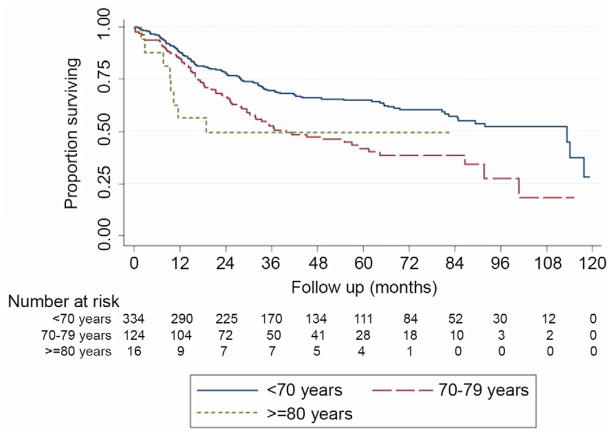

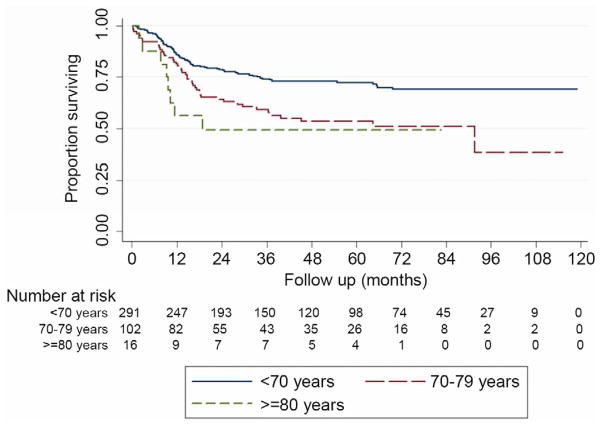

Survival analysis

Five-year overall survival was 58.1% for the entire cohort after a mean follow-up of 43.0 ± 30.8 months. Five-year OS was 64.8% for patients in group A, 41.7% in group B and 49.2% in group C as seen in Figure 1 (p=0.0006). Univariate and multivariate analysis for OS can be observed in Table 5. Cancer-specific survival was available for 409 (86.3%) subjects where esophageal cancer was the perceived cause of death for 131 patients, while the remaining 278 were alive or died of a different cause. Five-year CSS was 66.8% for the entire cohort and was 72.4% for patients in group A, 53.4% in group B and 49.2% in group C as seen in Figure 2 (p=0.0006). Increasing age was seen to be significantly associated with a decrease in OS and CSS, even when adjusting for gender, cancer histology, cancer stage, neoadjuvant therapy and the occurrence of major postoperative morbidity (Table 5).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival after esophagectomy stratified by age group.

Table 5.

Risk factor analysis for overall and cancer-specific survival in patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer

| VARIABLE | OVERALL SURVIVAL | CANCER-SPECIFIC SURVIVAL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (CI 95%) | p value | HR (CI 95%) | p value | HR (CI 95%) | p value | HR (CI 95%) | p value | |

| Age | ||||||||

| <70 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 70–79 years | 1.79 (1.33–2.41) | <0.001 | 1.50 (1.07–2.11) | 0.020 | 1.86 (1.29–2.69) | 0.001 | 1.50 (0.97–2.31) | 0.068 |

| ≥80 years | 1.98 (0.96–4.05) | 0.063 | 2.99 (1.40–6.38) | 0.005 | 2.45 (1.18–5.08) | 0.016 | 3.49 (1.59–7.68) | 0.002 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male | 1.04 (0.72–1.49) | 0.830 | 1.09 (0.73–1.63) | 0.676 | 0.92 (0.61–1.40) | 0.704 | 1.05 (0.65–1.69) | 0.842 |

| Histology | ||||||||

| High-grade dysplasia | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 4.10 (1.30–12.87) | 0.016 | 4.20 (0.67–26.20) | 0.124 | 3.53 (0.87–14.32) | 0.078 | 4.92 (0.47–51.70) | 0.184 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4.69 (1.43–15.37) | 0.011 | 3.55 (0.54–23.17) | 0.186 | 4.37 (1.02–18.76) | 0.047 | 4.05 (0.36–45.14) | 0.256 |

| Cancer Stage | ||||||||

| Stage 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Stage I | 0.60 (0.31–1.15) | 0.122 | 0.42 (0.11–1.61) | 0.207 | 0.45 (0.21–0.96) | 0.038 | 0.34 (0.08–1.45) | 0.145 |

| Stage II | 1.36 (0.73–2.56) | 0.335 | 0.91 (0.24–3.41) | 0.885 | 1.07 (0.52–2.19) | 0.856 | 0.79 (0.19–3.28) | 0.749 |

| Stage III | 2.97 (1.61–5.46) | <0.001 | 1.99 (0.54–7.37) | 0.301 | 2.64 (1.34–5.19) | 0.005 | 2.03 (0.50–8.16) | 0.319 |

| Stage IV | 3.81 (1.23–11.85) | 0.021 | 3.17 (0.59–17.01) | 0.178 | 4.29 (1.18–15.66) | 0.027 | 4.41 (0.69–28.22) | 0.117 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 1.22 (1.05–1.41) | 0.007 | 1.17 (0.98–1.38) | 0.072 | 1.20 (1.01–1.44) | 0.040 | 1.22 (0.98–1.51) | 0.071 |

| Postoperative major morbidity | 1.69 (1.27–2.25) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.14–2.15) | 0.005 | 2.01 (1.41–2.86) | <0.001 | 2.07 (1.39–3.07) | <0.001 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for cancer-specific survival after esophagectomy stratified by age group.

COMMENT

Life expectancy worldwide is growing and it is anticipated that by the year 2050 at least 16% of the world’s population will be at least 65 years old (20.5% in North America and 27.9% in Europe) [17]. The elderly patient is defined by the American Geriatrics Society as 75 years or more.[18] Age 70 or more was used in this analysis since most of the world’s esophageal literature defines 70 years as a cut off for the elderly. In 2009 Wright et al. [2] reported on cumulative data from the STS Thoracic Surgery Database where worse outcomes were observed in patients 75 years old compared to those 55 years old. Our data supports similar observations of published series on esophagectomy in the elderly [4–7,11,14] where patients ≥ 70 exhibited a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, hypertension and peripheral vascular disease compared to patients under 70. In contrast to some series [10,12,13], we observed a significant increase in postoperative major complications in patients >80 years at 62.5% compared to 47.6% in patients 70–79 years and 37.2% in patients <70 years. These morbidities were highlighted by a 2.5-fold increase in atrial fibrillation, a 3-fold increase in respiratory failure, and a 3-fold increase in pneumonia when ≥ 80 years old. Despite these observations, hospital length of stay was only 1 day longer (median 11 days) in the elderly compared to 10 days in patients < 70 years.

Interestingly, operative approach did not appear to influence short-term outcomes with advancing age. In contrast to a large study from the Netherlands [5] analyzing outcomes in 811 patients < 70 years old and 250 patients ≥ 70 years old, we did not find any increased morbidity with the use of a thoracoabdominal approach in elderly patients. This approach is often employed at our institution for distal esophageal tumors and can be advantageous in the obese patient by virtue of improved exposure. It has been our observation that elderly patients tolerate this incision very well provided it is oncologically appropriate. When specifically analyzing respiratory complications (using a composite of pneumonia, ARDS, ventilation >48 hr and respiratory failure) by operative approach, we found a trend towards less complications with MIE (p=0.077) and an increased risk with modified McKeown (p=0.010).

In patients 70–79 years old, we observed a leak rate of 4.8%, not significantly different when compared to those <70 years at 4.8%. Of note, only 1.1% (1/89) patients experienced a leak with a stapled anastomosis compared to 21/385 (5%) of patients with a hand sewn technique. We observed no leaks in patients > 80 years old. The notion that age is not an independent predictor of leak is concordant with previous series that have reported anastomotic leak rates of 3.9% – 22% in patients <70 years and 4.5% – 25% in older patients [4,6–11,13], with no significant difference. Data on anastomotic stricture rates in the elderly is not well defined. In 2003, Rahamim and colleagues [8] reported an anastomotic stricture rate of 25% in patients >70 years and 36% in patients <70 years (p=0.04) which is similar to our study observation of a decreasing stricture rate with advancing age (<70 years: 22.8%, 70–79 years: 10.5%, ≥80 years: 6.3%; p=0.005). Neoadjuvant therapy did not appear to contribute to the development of anastomotic stricture. Stricture was identified in 18.3% (41/222) of patients who received preoperative chemotherapy or radiation and in 18.5% (46/249) of patients who were not treated with induction therapy. This is an interesting finding and our study does not provide specific clues for its cause. However, we postulate that the normal inflammatory response to wound healing may be attenuated with increasing age perhaps leading to less collagen deposition and fibrosis.

There are very few contemporary case series [9,10] that document 90-day mortality after esophagectomy in the medical literature. Postoperative 30-day and 90-day mortality in the present study was 6.3% and 14.3% in patients ≥80 years, while it was 3.2% and 6.1% for patients 70–79 years and 0.6% and 2.2% for patients <70 years, respectively. We observed a 2.9-fold increase in 90-day mortality in patients undergoing esophagectomy age 70–79 and a 7.5-fold increase in patients > 80. Multivariate analysis confirmed that age and perioperative complications were independent predictors of OS and CSS in our series even after adjusting for possible confounders. Although there is some controversy in the world’s literature regarding the influence of age on mortality after esophagectomy, the majority of publications [4–8] report 30-day mortality rates of 0.7%–14% in patients <70 years and 6–18% in older patients, which were significantly different. Others [11–13] have reported 30-day mortality rates of 2.4%–3.3% in patients <70 years and 1.9%–7.6% in older patients, which were not different. Interestingly, one-year survival (which may be a more potent surrogate for perioperative mortality) was no different in our patients aged < 70 (87.7%) compared to ≥ 70 (82.7%).

Finally, increasing age was associated with reduced OS and CSS in patients undergoing esophagectomy in this analysis. Despite this trend, which has been corroborated by many single institution series [4,6,8,9,14], 5-year OS for patients ≥ 70 years old in this study (41.2%) is among the highest reported in the literature. This phenomenon cannot be attributed to earlier stage disease since 34% of elderly patients presented with stage III disease compared to 22% in patients < 70. Decreased OS may be attributed to comorbidities and reduced physiologic reserve; however, decreased CSS may be related to impaired immunosurveillance in the elderly, the unwillingness of medical or radiation oncologists to render multimodality therapy, or a conscious effort by a surgeon to attenuate the extent of the operation given advanced age. CSS rates have been reported to be similar between age groups [13,15] or to be decreased in elderly patients [5,6].

Our study has several limitations. There is an inherent selection bias in choosing patients for esophagectomy, particularly in those > 80 years old. Although some objective criteria (performance status, cardiopulmonary reserve, and tumor location) were used to deny patients an esophageal resection, surgeons’ judgment was difficult to measure. Furthermore, neoadjuvant therapy (predominately concurrent chemotherapy and radiation) was employed less frequently with advancing age (37% of patients aged 70–79, and 19% of patients > 80) compared to 52% of patients < 70 years old. This phenomenon may contribute to worse CSS. Quality of life assessment was not analyzed in this elderly cohort and represents a major limitation, which will be part of a subsequent study.

In summary, elderly patients (>70 years) with esophageal cancer present more frequently with comorbid conditions (especially cardiovascular disease), when compared to patients <70 years. More specifically, they have higher rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality, are less likely to develop anastomotic stricture, and experience decreased overall and cancer-specific survival rates. Multivariate analysis of the significant variables in this study did not identify tumor histology, cancer stage, gender or the use of neoadjuvant therapy as independent predictors of poor outcome in the elderly. Chronologic age should not be a sole criterion for recommending esophagectomy; however, it is more evident that offering this modality to patients > 70 years requires careful consideration and should be performed in centers of excellence. Overall, operative mortality in this series was very acceptable at 3.2% in patients 70–79, justifying esophagectomy in this age group. Patients ≥ 80 years old should be evaluated on a case by case basis since the risk of perioperative death can reach 6–14%. Earlier stage disease in the extreme elderly should first be referred for endoscopic techniques as an alternative to esophagectomy. As demographic and outcome variables for esophagectomy expand in the STS General Thoracic Database, more clinical parameters can be explored to assess risk in the elderly.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided by the Division of Thoracic Surgery at the Massachusetts General Hospital. This statistical analysis of this work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst (The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award 8UL1TR000170-05 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers)).

Footnotes

Presented at the 48th STS Annual Meeting, Ft. Lauderdale, FL.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sørensen HT, Funch-Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bytzer P, Christensen PB, Damkier P, Vinding K, Seersholm N. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and Barrett’s esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright CD, Kucharczuk JC, O’Brien SM, Grab JD, Allen MS. Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database. Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk adjustment model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(3):587–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poon RT, Law SY, Chu KM, Branicki FJ, Wong J. Esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus in the elderly: results of current surgical management. Ann Surg. 1998;227(3):357–64. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cijs TM, Verhoef C, Steyerberg EW, Koppert LB, Tran TC, Wijnhoven BP, et al. Outcome of esophagectomy for cancer in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(3):900–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang HX, Ling L, Zhang X, Lin P, Rong TH, Fu JH. Outcome of elderly patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma after surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97(6):862–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita M, Egashira A, Yoshida R, Ikeda K, Ohgaki K, Shibahara K, et al. Esophagectomy in patients 80 years of age and older with carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(5):345–51. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2171-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahamim JS, Murphy GJ, Awan Y, Junemann-Ramirez M. The effect of age on the outcome of surgical treatment for carcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23(5):805–10. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moskovitz AH, Rizk NP, Venkatraman E, Bains MS, Flores RM, Park BJ, et al. Mortality increases for octogenarians undergoing esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(6):2031–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pultrum BB, Bosch DJ, Nijsten MW, Rodgers MG, Groen H, Slaets JP, et al. Extended esophagectomy in elderly patients with esophageal cancer: minor effect of age alone in determining the postoperative course and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1572–80. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruol A, Portale G, Zaninotto G, Cagol M, Cavallin F, Castoro C, et al. Results of esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in elderly patients: age has little influence on outcome and survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(5):1186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang W, Igaki H, Tachimori Y, Sato H, Daiko H, Kato H. Three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal cancer in elderly patients over 70 years of age. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(3):867–71. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis FH, Jr, Williamson WA, Heatley GJ. Cancer of the esophagus and cardia: does age influence treatment selection and surgical outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187(4):345–51. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zehetner J, Lipham JC, Ayazi S, Banki F, Oezcelik A, DeMeester SR, et al. Esophagectomy for cancer in octogenarians. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23(8):666–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweet RH. Carcinoma of the esophagus and the cardiac end of the stomach immediate and late results of treatment by resection and primary esophagogastric anastomosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1947;135(8):485–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.1947.02890080015005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alibakhshi A, Aminian A, Mirsharifi R, et al. The effect of age on the outcome of esophageal cancer surgery. Ann Thorac Med. 2009;4(2):71–74. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.49415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population to 2300. United Nations; New York: 2004. ( http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/longrange2/WorldPop2300final.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 18.LoCicero J, Shaw PJ. Thoracic surgery in the elderly: Areas of future research studies. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009;19(3):409–13. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]