Abstract

Targeting transgene expression to specific hematopoietic cell lineages could contribute to the safety of retroviral vectors in gene therapeutic applications. Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a defect of phagocytic cells, can be managed by gene therapy, using retroviral vectors with targeted expression to myeloid cells. In this context, we analyzed the myelospecificity of the human miR223 promoter, which is known to be strongly upregulated during myeloid differentiation, to drive myeloid-restricted expression of p47phox and gp91phox in mouse models of CGD and in primary patient-derived cells. The miR223 promoter restricted the expression of p47phox, gp91phox, and green fluorescent protein (GFP) within self-inactivating (SIN) gamma- and lentiviral vectors to granulocytes and macrophages, with only marginal expression in lymphocytes or hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Furthermore, gene transfer into primary CD34+ cells derived from a p47phox patient followed by ex vivo differentiation to neutrophils resulted in restoration of Escherichia coli killing activity by miR223 promoter–mediated p47phox expression. These results indicate that the miR223 promoter as an internal promoter within SIN gene therapy vectors is able to efficiently correct the CGD phenotype with negligible activity in hematopoietic progenitors, thereby limiting the risk of insertional oncogenesis and development of clonal dominance.

Brendel and colleagues evaluate the properties of a DNA fragment derived from the human miR223 regulatory region as an internal promoter within self-inactivating (SIN) retroviral vectors for the gene therapy of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). They show that miR223-driven expression of gp91phox or p47phox efficiently corrects the CGD phenotype in mouse models. Importantly, the miR223-driven vector leads to negligible transgene expression in hematopoietic progenitors, which may reduce the risk of insertional oncogenesis and development of clonal dominance that is sometimes observed with SIN retroviral vectors.

Introduction

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) comprises a group of immunodeficiencies characterized by malfunctioning of the phagocytic nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, resulting in defective reactive oxygen species (ROS)–dependent killing of microbes and consequently leading to recurrent severe bacterial and fungal infections (Seger, 2008). About 67% of CGD cases result from mutations within the X-linked CYBB gene encoding the gp91phox subunit of NADPH oxidase (X-CGD), whereas 16% result from malfunction of the p47phox subunit (van den Berg et al., 2009).

The first clinically successful gene therapy (GT) trial for primary immunodeficiency was reported in 2000 (Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2000). Since then, the list of indications for which GT treatment led to permanent or temporary benefit for treated patients has been continuously growing (Aiuti et al., 2002; Mavilio et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2006; Ott et al., 2006; Kaplitt et al., 2007; Bainbridge et al., 2008; Cartier et al., 2009; Boztug et al., 2010; Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010; Porter et al., 2011).

For CGD, the first clinically successful X-CGD GT trial with proven restoration of ROS production and resolution of treatment refractory Aspergillus infections was initiated in 2004 in Frankfurt and Zürich. In this study, a gammaretroviral long terminal repeat (LTR)–driven vector containing a strong spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) promoter/enhancer was used to express gp91phox. However, vector-mediated transactivation of the EVI1 proto-oncogene in progenitor cells resulted in clonal dominance progressing to genetic instability and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (Stein et al., 2010). These severe side effects revealed the need of vector redesign to avoid vector-mediated genotoxic effects. This could be achieved by using vectors with self-inactivating (SIN) configuration and cell-type-specific internal enhancer/promoters, thereby restricting transgene expression to the deficient cell compartment (i.e., to granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages in CGD) and limiting the risk of proto-oncogene transactivation to cells with limited life span (reviewed in Toscano et al., 2011). Herewith, we tested the human miR223 regulatory region, which is highly active only in myeloid cells, in the context of SIN gamma- and lentiviral vectors (Fukao et al., 2007) for its expression specificity, stability over time, and its ability to restore NADPH oxidase function and mediate bacterial killing.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-human CD14-FITC, anti-human CD206-FITC (clone 19.2), anti-Ly6G-FITC (clone 1A8), anti-Gr1-PE (clone RB6-8C5), anti-B220-FITC or APC-Cy7 (clone RA3-6B2), anti-CD3-PE (clone 17A2), anti-CD11b-PE (clone M1/70), anti-ScaI-PE (clone E13-161.7), mouse Fc-block (clone 2.462), and Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit were from Beckton Dickinson (Basel, Switzerland), as was anti-p47phox (clone 1)-APC labeled by Beckton Dickinson services. Anti-CD11b-PerCP/Cy5.5, APC or PE-Cy7 (clone M1/70), anti-F4/80-PerCP/Cy5.5 (clone BM8) and anti-CD117-FITC or APC (clone 2B8), CD45.1-PE or PE-Cy7 (clone A20), CD45.2-PercP-Cy5.5 (clone 104), and ScaI-PE-Cy7 (clone D7) were from eBiosciences (Vienna, Austria). Anti-CD11C-PerCP (clone N418) came from Biolegend (Uithoorn, The Netherlands). Anti-ΔLNGFR-APC, human and mouse Lineage Cell Depletion Kits, CD14 microbeads, and Gr1-VioBlue (clone RB6-8C5) were from Miltenyi Biotec GmbH (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For intracellular p47phox staining combined with surface staining, cells were blocked for 10 min at 4°C, incubated with surface staining antibodies for 1 hr, and washed twice followed by intracellular staining using Cytofix/Cytoperm according to manufacturer's description.

Animals

p47phox–/– (B6[Cg]-Ncf1m1J/J) and gp91phox–/– (B6.129S-Cybbtm1Din/J) mouse husbandry and animal experiments were carried out in compliance with the local animal protection law.

Vector construction

The 5′ regulatory region of the human miRNA223 promoter (782 bp, chrX:65,234,612-65,235,394 GRCh37/hg19 assembly) was amplified from PLB985 gDNA using the following primers: forward, 5′-CATATGACTTGTACAGCT TCACAGGGCTCC (NdeI linker); reverse, 5′-GGATCCCTGT CAGTGGAGTGGTGC (BamHI linker). This element was cloned into lentiviral vectors via the NdeI–BamH1 sites to replace the MRP8 promoter in the MRP8-gp91-wPRE (MgpW) vector (Brendel et al., 2011) or the corresponding GFP-containing MEW vector. Gammaretroviral constructs were derived from the pSER11M8ΔN91s vector (M. Grez) by exchanging the transgene against a synthetic human p47phox reading frame (Geneart, Regensburg, Germany) and by exchanging the internal promoter against promoter candidates (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Material available online at www.liebertonline.com/hgtb). The gammaretroviral vector encoding SFFV:ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox was already described (Wohlgensinger et al., 2010). In this construct, the SFFV promoter was exchanged against the miR223 promoter. Lentiviral vectors encoding miR223 p47phox were derived from the pCCL.CHIM.GP91phox.WPRE (Santilli et al., 2011) by exchanging the promoter and the transgene.

Virus production

Virus supernatants were produced in 293T cells upon co-transfection with pMD2.VSV.G with CMVΔR8.91 for lentiviral vectors or pUMVS plus the gene transfer vector for gammaretroviral vectors (Supplementary Fig. S1), using TransIT-293 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI) or calcium phosphate–mediated transfection. Culture supernatants were collected after 24 and 48 hr, sterile-filtered, concentrated in Ultracal-100K Centrifugal Filters (Millipore, Zug, Switzerland) or by ultracentrifugation (2 hr at 50,000 g at 4°C), and stored at −80°C.

Transduction and ex vivo granulocytic differentiation

Murine lineage-negative (Lin–) bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated from femur and tibias of 6–12-week-old mice using the Miltenyi lineage cell depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH). The cells were prestimulated for 24 hr in StemSpan SFEM (StemCell Technologies, Grenoble, France) supplemented with mouse stem cell factor (mSCF) (10 ng/ml), mouse thrombopoietin (mTPO) (20 ng/ml), mouse insulin-like growth factor 2 (mIGF-2) (20 ng/ml), and human fibroblast growth factor 1 (hFGF1) (10 ng/ml) (all from Peprotech, Hamburg, Germany) at 0.5×106 to 1×106 cells per milliliter. Transduction was carried out at 20–50 multiplicity of infections (MOIs) in the presence of protamine sulfate (6 μg/ml) for 24 hr in 24-well plates. The cells were cultivated for another 24 h before transplantation. For granulocytic differentiation in vitro, the cells were incubated in RetroNectin (Takara Bio Europe/SAS, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) plates in differentiation medium 1 (RPMI) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 25 ng/ml mouse granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (mG-CSF) for 3 days up to 2 weeks.

After informed consent, human Lin– cells were isolated from BM aspirates of a p47phox CGD patient, using the Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH). Lin– BM cells were expanded for 3 days on 24-well plates coated with RetroNectin in X-Vivo 10, penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 ng/ml human interleukin-3 (hIL-3), 150 ng/ml human stem cell factor (hSCF), 150 ng/ml human FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (flt3) ligand (hFlt3L), 50 ng/ml human thrombopoietin (hTPO), and 2% FCS (or 1% bovine serum albumin). For retroviral transduction, cells were harvested and centrifuged onto virus preloaded RetroNectin plates.

For ex vivo differentiation, cells were harvested again and seeded on RPMI (10% FCS, penicillin/streptomycin, 50 ng/ml hSCF, 10 ng/ml human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (hG-CSF), 10 ng/ml hFLT3L) at day 1. At day 10, cells were shifted to differentiation medium 2 (differentiation medium 1 without SCF) and incubated for another 10 days, followed by FACS sorting using a BD FACSAria Flow Cytometer (Beckton Dickinson, Basel, Switzerland).

Animal GT

p47phox–/– and gp91phox–/– mice received lethal (9.5 Gy or a split dose of 2×5.5 Gy) irradiation. About 1×106 to 2×106 gene-modified Lin– BM cells were injected intravenously. Animals were sacrificed after 7–23 weeks, and blood, spleen, BM, and peritoneal macrophages were analyzed for transgene expression.

Escherichia coli killing assay

The assay was conducted as described recently (Ott et al., 2006) with minor modification. Granulocytes were co-incubated with opsonized E. coli at a ratio of 1:10 for 30 min at 32°C. Essentially, neutrophils were incubated with the E. coli strain ML-35. This particular strain lacks the membrane transport protein lactose permease and constitutively expresses β-galactosidase (β-Gal). Engulfment of E. coli ML-35 by neutrophils is followed by perforation of the bacterial cell wall and accessibility to β-Gal, which is subsequently inactivated by ROS (Hamers et al., 1984). Briefly, 2×109 E. coli/ml were opsonized with 20% (v/v) Octaplas (Octapharma AG, Lachen, Switzerland) for 5 min at 37°C. Opsonized E. coli (final concentration, 0.9×108/ml) were added to granulocytes (0.9×107/ml). At defined time points, granulocytes were lyzed with 0.05% saponin (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) and the samples were incubated with 1 mM ortho-nitrophenyl-βD-galactopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich, Seelze, Germany) at 37°C for 30 min. β-Gal activity was followed by standard procedures at 420 nm.

Human monocytes/macrophage culture

After informed consent, human monocytes were isolated using CD14 microbeads. Cryostorage in CryoSto CS10 (StemCell Technologies) resulted in 30% survival upon thawing. Monocytes were cultured, transduced at a high MOI, and differentiated to macrophages in RPMI, 10% Octaplas, 2 mM L-Gln, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, and M-CSF 100 ng/ml.

Nitroblue tetrazolium test

Macrophages were incubated in 1 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT; Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Buchs, Switzerland) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 200 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) plus 0.5 nmol/ml N-Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) (both from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH) for 1 hr at 37°C and fixed thereafter in PBS and 2% formaldehyde (Merck [Schweiz] AG, Zug, Switzerland). Photographs were taken on a Leica DM-IL microscope with a DFC-480 camera (Leica Microsystems [Schweiz] AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland).

Dihydrorhodamine 123 assay

About 106 granulocytes in 1 ml of Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with Ca/Mg, 0.5% human albumin, 1000 U catalase, 7.5 mM glucose, and antibodies were stimulated with 200 ng PMA and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Then, dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR) was added to a final concentration of 0.435 μM, incubated for further 15 min at 37°C, kept on ice for 30 min, and analyzed using FACS Calibur (Beckton Dickinson, Basel, Switzerland) or FACS Canto II (Beckton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

Results

The miR223 promoter induces transgene expression upon granulocytic differentiation in vitro

To identify a myeloid-restricted promoter adequate for the gene therapy of CGD, we analyzed the promoter activity of a 782-bp DNA fragment derived from the human miR223 promoter within SIN gamma- and lentiviral vector constructs, as earlier reports have indicated strong and specific upregulation of miR223 gene expression during myeloid differentiation (Fukao et al., 2007; Landgraf et al., 2007; Johnnidis et al., 2008). We tested the miR223 promoter in conjunction with the gp91phox and the p47phox subunits of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase as well as with a ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox fusion construct (Wohlgensinger et al., 2010) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

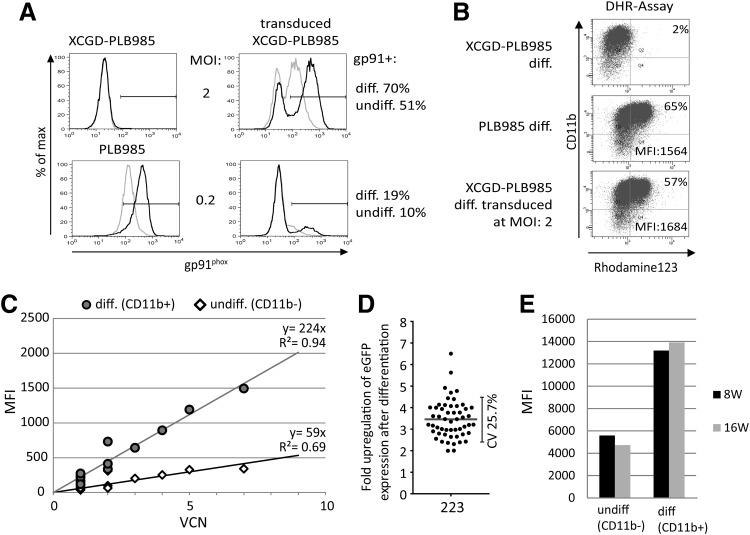

Initially, we transduced murine Lin– BM cells obtained from p47phox–/– animals with SIN gammaretroviral vectors harboring p47phox under control of the miR223 promoter, and compared this with the specificity of other promoters derived from myeloid-restricted genes such as cFES (Heydemann et al., 2000) and MRP8 (Brendel et al., 2011), or synthetic promoters like the p40/48 (a 250-nt chimeric promoter consisting of two PU.1 transcription factor binding sites from the p40 and one PU1 site from the p47 promoter), or the Sp107 (He et al., 2006) promoters. We used the SFFV promoter as a benchmark for high expression levels in myeloid cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). p47phox expression was analyzed by FACS upon intracellular p47phox staining 2 days after transduction in ScaI+ cells as well as in ex vivo differentiated Ly6G+ granulocytes generated thereof (Supplementary Fig. S2A). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ratio of p47phox expression in differentiated versus undifferentiated cells was used to estimate the induction of transgene expression upon myeloid differentiation. In this screen, the miR223 promoter showed the strongest induction of p47phox expression among the promoters tested (Supplementary Fig. S2C). In addition, differentiated cells were analyzed for ROS production in a DHR oxidation assay. We observed a consistent increase in DHR+ granulocytes from cFes, p40/48, and the miR223-corrected cells, but only the miR223-corrected population showed a statistically significant increase of DHR+ cells compared with the mock control (Supplementary Fig. S2B and D). Next, we transduced the human myelomonocytic cell line X-CGD PLB985 with a lentiviral SIN vector encoding gp91phox under control of the miR223 promoter (223gpW). Transductions at MOIs of 2 and 0.2 resulted in moderate gp91phox expression levels in 51% and 10% of the cells, respectively. Upon differentiation, the percentage of gp91phox-expressing cells increased to 70% and 19%, respectively, in parallel to a significant increase in expression levels (Fig. 1A). Restoration of ROS production could be confirmed in 57% of the cells transduced at an MOI of 2, with DHR MFIs comparable to those of differentiated wild-type PLB-985 cells (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Performance of miR223 promoter–containing lentiviral vectors in the human myelomonocytic X-CGD cell line PLB985. (A) FACS analysis of gp91phox expression in undifferentiated (gray) and differentiated (black) X-CGD-PLB985 cells transduced with 223gpW at MOIs 2 and 0.2 along with nontransduced controls. (B) NADPH oxidase activity in 223gpW-transduced X-CGD-PLB985 cells assessed by the DHR assay. (C) Correlation of VCN and GFP expression levels in undifferentiated (diamonds) and differentiated (circles) PLB985 clonal cell populations transduced with 223GFP. (D) Fold upregulation of GFP expression levels during granulocytic differentiation in clonal populations derived from 223GFP-transduced PLB985 cells. Variation of expression levels is given as percentage of coefficient of variation (%CV). (E) Cumulative long-term stability of GFP expression in 223GFP-transduced PLB985 cells during a 4-month culture period in differentiated and undifferentiated clonal populations. CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; DHR, dihydrorhodamine 123; GFP, green fluorescent proten; MOI, multiplicity of infection; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; VCN, vector copy number.

We generated single clones of PLB-985 cells transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding GFP under control of the miR223 promoter in order to quantify gene expression without variations resulting from antibody staining. The analysis revealed a good correlation between vector copy number (VCN) and transgene expression particularly in differentiated cells (R2=0.94), whereas a reduced correlation was evident in undifferentiated cells (R2=0.69) (Fig. 1C). In 53 monoclonal populations, the mean fold induction of GFP expression upon granulocytic differentiation was 3.5±0.88 (Fig. 1D) with a coefficient of variation of only 25.7%. Moreover, GFP signals in these clones remained stable during the total observation period of 4 months (Fig. 1E).

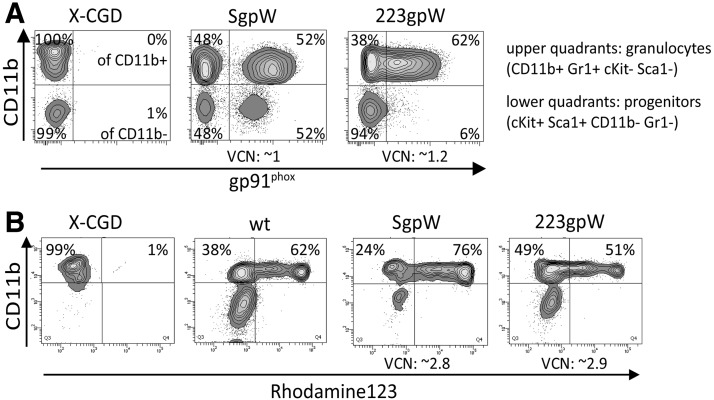

The induction of transgene expression and reconstitution of NADPH oxidase activity could also be confirmed in granulocytes obtained upon ex vivo differentiation of transduced murine Lin– gp91phox–/– BM cells. Lentiviral transduction with the vector harboring gp91phox under SFFV promoter control (SgpW) resulted in similar expression of gp91phox in hematopoietic progenitors (cKit+ ScaI+) and granulocytes (CD11b+ Gr1+) (Fig. 2A) with good reconstitution of ROS production in differentiated CD11b+ Gr1+ cells (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, the miR223 promoter (223gpW) mediated weak gp91phox expression in a small fraction (6%) of the hematopoietic progenitors (cKit+ ScaI+ CD11b– Gr1–), whereas 62% of the CD11b+ Gr1+ cells showed significant amounts of gp91phox expression, confirming induction of miR223 promoter activity upon granulocytic differentiation. As in PLB-985 cell–derived granulocytes (Fig. 1B), miR223-driven gp91phox expression also mediated high levels of ROS production in granulocytes derived from transduced primary murine Lin– cells with ROS levels similar to those observed in granulocytes derived from wild-type (C57Bl6) or SgpW-transduced X-CGD cells (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Expression of gp91phox and NADPH oxidase activity after in vitro culture of 223gpW-transduced murine X-CGD Lin– BM cells. (A) 223gpW-transduced murine Lin– cells were analyzed for gp91phox expression in stem and progenitor cells (lower quartiles) and in granulocytes (upper quartiles). (B) Functional reconstitution of NADPH oxidase activity in X-CGD neutrophils mediated by the recombinant expression of gp91phox as assessed by the DHR assay. BM, bone marrow; Lin–, lineage-negative.

Collectively, these results strongly indicate an induction of miR223 promoter activity upon granulocytic differentiation regardless of transgene identity or the vector system utilized.

The miR223 promoter drives myelo-specific transgene expression in CGD mouse models in vivo

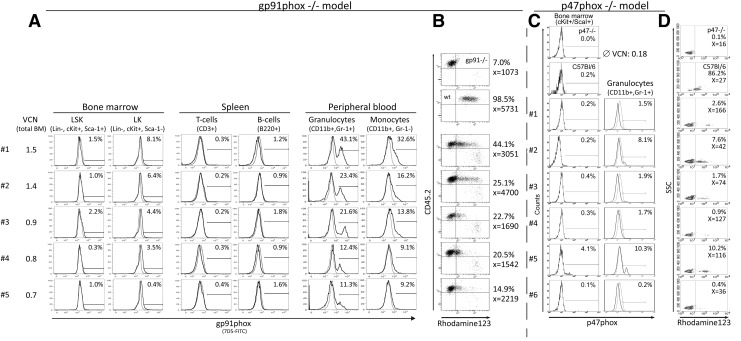

To characterize the miR223 promoter activity in vivo, we monitored transgene expression patterns in gp91–/– and p47–/– mouse models of CGD. After lentiviral transduction of X-CGD Lin– BM cells with 223gpW and reinfusion into lethally irradiated recipient mice, gp91phox expression was analyzed in donor cells up to 23 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 3A and B; Supplementary Fig. S3). Expression in BM LSK (Lin– ScaI+ cKit+) cells and lymphoid cells (CD3+ or B220+) was almost undetectable, while increasing amounts of gp91phox were detected during differentiation from progenitor LSK cells (Lin– ScaI– cKit+) to monocytes (CD11b+ Gr1–) and to mature granulocytes (CD11b Gr1+). Gp91phox expression in granulocytes led to the reconstitution of NADPH oxidase activity and ROS production as analyzed by the DHR assay. The percentages of DHR+ granulocytes correlated with the percentages of gp91phox expression in individual animals, and DHR MFIs indicate the production of significant amounts of ROS at moderate VCNs between 0.7 and 1.5 (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

In vivo expression profile of miR223 promoter–driven gp91phox or p47phox vectors. (A) Lentivirally (223gpW) transduced Lin– BM cells from gp91phox–/– (CD45.2) mice were transplanted into irradiated SJL mice (CD45.1). Expression of gp91phox in different donor-derived hematopoietic lineages was determined 23 weeks after transplantation by flow cytometry. Shown in overlay histograms: gray, gp91–X-CGD-PLB985 cells; black, transduced sample. (B) Analysis of the NADPH oxidase activity in peripheral blood granulocytes derived from the mice shown in (A). (C) Lin– BM cells from p47–/– mice were gammaretrovirally (miR223 p47phox) transduced and transplanted into congenic recipient mice. Analysis of p47phox expression and reconstitution of NADPH oxidase activity (D) was performed 8 weeks after transplantation.

In the p47–/– animal model, an miR223 p47phox gammaretroviral vector (Supplementary Fig. S1) was used to transduce syngeneic Lin– BM cells, and cell populations were analyzed for p47phox expression by intracellular staining 7 weeks after reinfusion (Fig. 3C). Very low expression of p47phox was observed in BM cKit+ ScaI+ or splenic T and B cells (data not shown), and expression levels in monocytes remained under the detection limit. Expression levels in granulocytes were below 11% at an average of 4%, indicating one copy per cell (Fehse et al., 2004). Although MFIs of p47phox+ granulocyte signals were moderate, ROS production was restored in all animals (Fig. 3D). The percentages of DHR+ granulocytes closely correlated with the percentages of p47phox FACS+ granulocytes (R2=0.9872). No adverse events regarding animal health, organ size, and appearance were observed during these studies. Furthermore, there was no decline of expression over time, which might indicate the absence of epigenetic silencing.

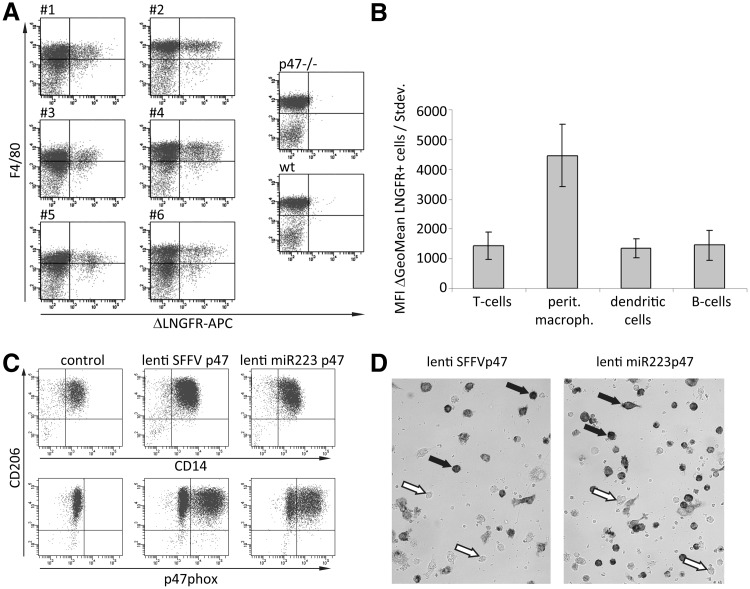

The miR223 promoter is active in p47phox-deficient macrophages

As NADPH oxidase function is required in granulocytes and in macrophages, we tested transgene expression in peritoneal macrophages of NADPH oxidase–deficient animals. Lethally irradiated p47phox–/– mice were reconstituted with Lin– cells transduced with a gammaretroviral vector encoding the ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox fusion construct under miR223 control, allowing for indirect p47phox detection by ΔLNGFR surface staining (Wohlgensinger et al., 2010).

Significant ΔLNGFR expression was observed in F4/80+ peritoneal macrophages in all treated animals, indicating miR223 promoter activity in macrophages (Fig. 4A), while ΔLNGFR detection signals in splenic T and B cells and blood dendritic cells were in the range of background staining (Fig. 4B). Next, we analyzed the miR223 promoter activity in primary human macrophages obtained from blood monocytes of a p47phox-deficient CGD patient. Monocytes were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding p47phox under control of the SFFV or the miR223 promoter and differentiated to macrophages for 7 days, resulting in high levels of transduction for both vectors (Fig. 4C). ROS production in primary macrophages was confirmed in an NBT reduction assay upon PMA/fMLP stimulation (Fig. 4D), clearly indicating miR223 promoter activity in this cell type.

FIG. 4.

miR223 promoter activity in macrophages. Lin– BM cells from p47phox–/– mice were gammaretrovirally transduced (miR223-ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox) and reinfused into lethally irradiated p47phox–/– mice. FACS analysis of (A) ΔLNGFR expression in peritoneal macrophages and (B) T, B, and dendritic cells after 8 weeks revealed preferential expression in peritoneal macrophages. (C) Frozen blood monocytes from a p47phox CGD patient were taken into culture overnight and lentivirally (miR223-p47phox) transduced. The cells were kept in culture for 7 days, followed by FACS analysis of p47phox expression in macrophages (CD206+ CD14+). (D) Functional reconstitution of ROS production was analyzed in macrophages by nitroblue tetrazolium assay. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

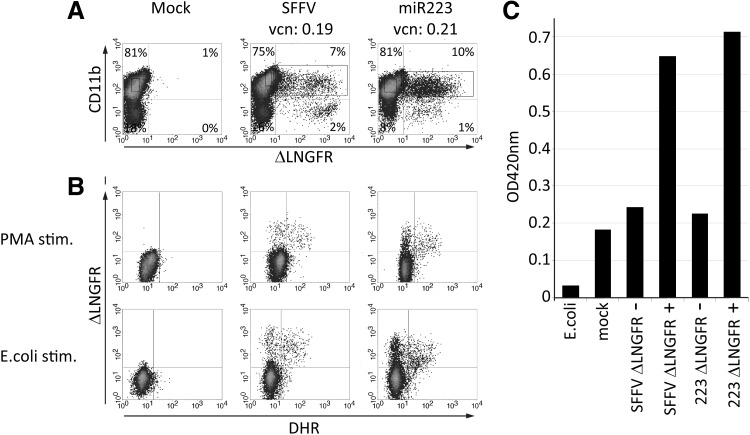

The miR223 promoter–controlled p47phox expression restores E. coli killing activity in primary human granulocytes

To analyze whether miR223 promoter–driven p47phox expression restores granulocyte anti-microbial activity, we transduced Lin– BM cells from a p47phox-deficient CGD patient with the gammaretroviral vector encoding the ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox fusion construct under miR223 or SFFV transcriptional control followed by granulocytic differentiation ex vivo. ΔLNGFR surface staining circumvents intracellular staining for p47phox for functional analyses and allows for the enrichment of gene-modified cells. In differentiated myeloid cells, gene marking rates of 7%–10% were observed (Fig. 5A). Stimulation of these cells with either PMA or opsonized E. coli resulted in DHR oxidation exclusively in ΔLNGFR+ cells, indicating restoration of ROS production in a p47phox-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). ΔLNGFR surface marking of neutrophils, together with CD11b marking of differentiated granulocytes, was used to FACS-sort mock-transduced p47phox+ (ΔLNGFR+) and p47phox– (ΔLNGFR–) granulocytes (all CD11b+) derived from γRetro-SIN miR223-ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox and γRetro-SIN SFFV-ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox–transduced cells. Sorted cell populations were then analyzed in an E. coli killing assay (Ott et al., 2006). In this assay, an increase in optical density at 420 nm indicates effective bacterial killing. Both ΔLNGFR+ populations showed effective restoration of E. coli killing activity, whereas the CD11b+/ΔLNGFR– populations derived from the same cultures were unable to kill E. coli (Fig. 5C). Thus, antimicrobial function was restored in neutrophils expressing p47phox under control of the miR223 (as well as SFFV) promoter. These data reinforce the potential utility of the miR223 promoter for high and myeloid-restricted transgene expression.

FIG. 5.

E. coli killing activity of ex vivo differentiated human p47phox–/– granulocytes after gene transfer. Lin– cells from a p47–/– CGD patient were mock transduced or gammaretrovirally transduced with the self-inactivating SFFV-ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox or the self-inactivating miR223-ΔLNGFR-2A-p47phox vectors and propagated to granulocytes in liquid cell culture. (A) Expression of the surrogate marker ΔLNGFR reflecting p47phox expression in myeloid differentiated (CD11b+) and undifferentiated (CD11b–) cells. (B) Within the CD11b/ΔLNGFR double-positive populations, 0.1%, 48.7%, and 49.1% responded by ROS production upon stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate as revealed in the DHR assay (upper panels). Stimulation with opsonized E. coli (lower panels) resulted in ROS production in 1.3%, 32.1%, and 35.5% of the double-positive cells. (C) Transduced CD11b+ cells were separated by FACS as indicated by the ΔLNGFR gates shown in (A) (purity: SFFV, 87%; miR223, 93%). The isolated populations were analyzed for their E. coli killing capacity in a standard killing assay using the E. coli strain ML35. An increase in optical density at 420 nm indicates bacterial killing activity.

Discussion

Transactivation of proliferation-promoting genes as the primary cause of clonal dominance in gene therapy studies can potentially be avoided by the use of SIN vectors driving transgene expression from an internal tissue-specific promoter rather than from strong constitutively active promoters such as the viral LTR (Zychlinski et al., 2008; Modlich et al., 2009; Montini et al., 2009). Another potential risk arises from transcriptional read-through, that is, the extension of viral transcripts through the virus–genome border into the genomic sequence or splicing of vector transcripts into cellular exons. Both features have contributed to leukemia formation in animal models and clinical studies (Cesana et al., 2012). For CGD, a myelo-specific promoter driving transgene expression preferentially in phagocytes could be an option to limit transgene expression to short-lived cells, thereby theoretically limiting the risks associated with enhancer- or read-through–mediated activation of proto-oncogenes (Kustikova et al., 2009; Toscano et al., 2011). The study was motivated by the results obtained during the long-term follow-up of CGD patients treated by gene therapy revealing transactivation of EVI1 as primary cause of clonal dominance with development of MDS, and promoter silencing leading to treatment failure (Stein et al., 2010).

In our study, we evaluated the properties of a DNA fragment derived from the human miR223 regulatory region as an internal promoter within SIN retroviral vectors for the gene therapy of CGD, as the hsa-miR223 gene was reported to be transcribed nearly exclusively within the hematopoietic compartment (Landgraf et al., 2007) in a highly myeloid-specific manner (Fukao et al., 2007; Johnnidis et al., 2008).

In the gp91phox-deficient mouse model, miR223-driven gp91phox expression resulted in up to 43% gp91phox+ granulocytes, but the same resulted in only 0.3%–2.2% gp91phox+ early stem and progenitor cells (LSK cells) and in a maximum of 1.8% positive T and B cells, as assessed by intracellular staining despite mean VCNs of 0.7–1.5 (Fig. 3A). The lack of gp91phox expression in immature primitive progenitors and B and T cells could be attributed to a detection bias, as gp91phox is not stable in cells lacking p22phox, the second component of the cytochrome b558 complex. However, p22phox is ubiquitously expressed (Chambers et al., 2007) and gp91phox can be easily detected in LSK cells transduced with SgpW, a lentiviral vector containing the SFFV enhancer/promoter element driving gp91phox expression (Fig. 2A) (Brendel et al., 2011). Similarly, in the p47phox model, miR223-mediated p47phox expression was weak in BM cKit+/ScaI+ cells and undetectable in T and B cells, while neutrophils were up to 10.3% p47phox+. Although the analyses of both models were performed at different time points, hematopoiesis after 7 or more weeks is mainly maintained by mid- and long-term repopulating multipotent progenitors (Dykstra et al., 2007; Gerrits et al., 2010). Therefore, lineage-specific expression is unlikely to originate from the transduction of lineage-restricted progenitors but rather truly reflects the specificity of the miR223 promoter element. The expression distribution observed in our experiments resembles the expression pattern of the miR223 gene in mice (Johnnidis et al., 2008) and humans (Allantaz et al., 2012). Moreover, our in vitro experiments show that the miR223 promoter can direct gp91phox expression in a VCN-dependent manner and generates levels of superoxide equivalent to those observed in differentiated wild-type human myeloid cell lines and in vitro differentiated murine neutrophils (Figs. 1 and 2).

Myeloid-restricted expression of the miR223 gene has been attributed to the action of a complex regulatory loop including the coordinate binding of CEBP and PU.1 to a region upstream of the major pri-miR223 transcription start site (MTSS) and to the binding of C/EBPα and NFI-A to a nonconserved responsive element 2710 bp downstream of the MTSS, which corresponds to an intron of the pri-miR223 transcript (Fukao et al., 2007). Although the detailed interplay of these two regulatory regions in mediating tissue specificity has not been clarified, evidence exists that the intronic regulatory region contributes to miR223 expression specificity (Fazi et al., 2007). The DNA fragment used in our studies comprises the MTSS and includes the CEBP and PU.1 sites but lacks the binding sites for C/EBPα and NFI-A. Despite this, a myeloid-restricted expression pattern was observed in vitro and in vivo.

A recent study characterized a myelo-specific chimeric promoter generated by the fusion of cathepsin G and c-Fes minimal 5′-flanking regions driving gp91phox expression within a lentiviral SIN vector (Santilli et al., 2011). In comparison to this vector, the 223gpW exhibits even lower leakiness in lymphocytes and more importantly in LSK cells. One possible explanation for this is the lack of SP1-binding sites in the miR223 DNA fragment used in this study, which are present in the chimeric promoter and which may account for the low levels of gene expression seen in primitive progenitors transduced with SIN vectors containing the chimeric promoter (Santilli et al., 2011).

Alternatively, miRNA target sequences can also be used to restrict transgene expression to the desired target population (Brown et al., 2007). Best example of this is the use of the miR126 target sequences to detarget expression of an otherwise toxic gene product (galactocerebrosidase) from HSCs in the context of gene therapy for globoid cell leukodystrophy (Gentner et al., 2010).

Although targeting gene expression to myeloid cells in the context of CGD is a reasonable approach, there is no experimental evidence for a toxic effect of gp91phox expression in hematopoietic primitive progenitor cells (Grez et al., 2011). Thus, the relevant issue for CGD vectors is the absolute reconstitution of superoxide levels, as the analysis of 227 CGD patients revealed a close correlation between superoxide production levels and long-term survival (Kuhns et al., 2010).

Unfortunately, a restricted tissue-specific transgene expression frequently yields weak expression levels. The question is whether, despite the high specificity, miR223-mediated expression levels are sufficient to correct the CGD phenotype.

In our hands, FACS-sorted p47phox+ neutrophils derived from the BM cells of transduced Lin– p47phox-deficient patients clearly demonstrated E. coli killing activity ex vivo for both SFFV- and miR223-containing vectors compared with the fraction of untransduced neutrophils, indicating that the level of miR223-mediated p47phox expression in neutrophils is sufficient to restore the physiological antimicrobial function of these cells (Fig. 5).

ROS production seems to possess a triggering role for antimicrobial defense mechanisms, and it is a prerequisite for NET formation and extracellular killing (Bianchi et al., 2009). Already, very low amounts of granulocytic ROS production result in significant changes in membrane potential, K+ efflux, and bacterial killing (Rada et al., 2004). This indicates that low levels of gp91phox or p47phox expression in CGD phagocytes could result in significant physiological improvement in the clinical status of treated patients. In mice, already 4%–8% of wild-type granulocytes or 11%–21% gene-modified neutrophils were sufficient to protect X-CGD mice against respiratory challenge with Aspergillus fumigatus conidia, although a significant higher number of gene-corrected neutrophils was required to improve host defense of X-CGD animals against Staphylococcus aureus and Burkholderia cepacia (Dinauer et al., 2001; Urban et al., 2009; Bianchi et al., 2011). We expect our tissue-specific miR223 vectors to show an improved safety profile compared to vectors with ubiquitously active promoters, as our highly myelo-specific expression pattern strongly limits the promoter activity in stem and progenitor cells and thus may prevent the occurrence of side effects while restoring the physiological antimicrobial function of gene-corrected neutrophils.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work done by C.B., L.C.-W., and M.G. was supported by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Grants 01GU0811, TP2b, and E-RARE 01GM1012), the Research Priority Program 1230 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the European Union (FP7 integrated project CELL-PID HEALTH-2010-261387), and the LOEWE Center for Cell and Gene Therapy Frankfurt funded by the Hessische Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst (HMWK; funding reference number: III L 4-518/17.004 [2010]). J.R. was supported by “Gebert Rüf Stiftung: Programme Rare Diseases—New Approaches” and EU-FP 7 CELL PID.

We thank Support of Young Scientist by Zürich University, Swiss National Science Foundation SNF (Grant number 320000-121983), and Theodor and Ida Herzog-Egli Foundation. We also thank Romain Zuffery and Sen Lin Li for promoter constructs and Prof. A. Thrasher for the pCCL.CHIM.GP91phox.WPRE vector. Novartis Stiftung für Medizinisch-Biologische Forschung enabled animal experiments. The Georg-Speyer-Haus is supported by the Bundesministerium für Gesundheit and the Hessisches Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Aiuti A. Slavin S. Aker M., et al. Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Science. 2002;296:2410–2413. doi: 10.1126/science.1070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allantaz F. Cheng D.T. Bergauer T., et al. Expression profiling of human immune cell subsets identifies miRNA-mRNA regulatory relationships correlated with cell type-specific expression. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge J.W. Smith A.J. Barker S.S., et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M. Hakkim A. Brinkmann V., et al. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood. 2009;114:2619–2622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M. Niemiec M.J. Siler U., et al. Restoration of anti-Aspergillus defense by neutrophil extracellular traps in human chronic granulomatous disease after gene therapy is calprotectin-dependent. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;127:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.021. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boztug K. Schmidt M. Schwarzer A., et al. Stem-cell gene therapy for the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1918–1927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendel C. Muller-Kuller U. Schultze-Strasser S., et al. Physiological regulation of transgene expression by a lentiviral vector containing the A2UCOE linked to a myeloid promoter. Gene Ther. 2011;19:1018–1029. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.D. Gentner B. Cantore A., et al. Endogenous microRNA can be broadly exploited to regulate transgene expression according to tissue, lineage and differentiation state. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1457–1467. doi: 10.1038/nbt1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier N. Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Bartholomae C.C., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M. Hacein-Bey S. De Saint Basile G., et al. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M. Payen E. Negre O., et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human beta-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesana D. Sgualdino J. Rudilosso L., et al. Whole transcriptome characterization of aberrant splicing events induced by lentiviral vector integrations. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:1667–1676. doi: 10.1172/JCI62189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S.M. Boles N.C. Lin K.Y., et al. Hematopoietic fingerprints: an expression database of stem cells and their progeny. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:578–591. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer M.C. Gifford M.A. Pech N., et al. Variable correction of host defense following gene transfer and bone marrow transplantation in murine X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Blood. 2001;97:3738–3745. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra B. Kent D. Bowie M., et al. Long-term propagation of distinct hematopoietic differentiation programs in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazi F. Racanicchi S. Zardo G., et al. Epigenetic silencing of the myelopoiesis regulator microRNA-223 by the AML1/ETO oncoprotein. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehse B. Kustikova O.S. Bubenheim M. Baum C. Pois(s)on—it's a question of dose. Gene Ther. 2004;11:879–881. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T. Fukuda Y. Kiga K., et al. An evolutionarily conserved mechanism for microRNA-223 expression revealed by microRNA gene profiling. Cell. 2007;129:617–631. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner B. Visigalli I. Hiramatsu H., et al. Identification of hematopoietic stem cell-specific miRNAs enables gene therapy of globoid cell leukodystrophy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:58ra84. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrits A. Dykstra B. Kalmykowa O.J., et al. Cellular barcoding tool for clonal analysis in the hematopoietic system. Blood. 2010;115:2610–2618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grez M. Reichenbach J. Schwable J., et al. Gene therapy of chronic granulomatous disease: the engraftment dilemma. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:28–35. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers M.N. Bot A.A.M. Weening R.S., et al. Kinetics and mechanism of the bactericidal action of human neutrophils against Escherichia coli. Blood. 1984;64:635–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W. Qiang M. Ma W., et al. Development of a synthetic promoter for macrophage gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:949–959. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydemann A. Warming S. Clendenin C., et al. A minimal c-fes cassette directs myeloid-specific expression in transgenic mice. Blood. 2000;96:3040–3048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnnidis J.B. Harris M.H. Wheeler R.T., et al. Regulation of progenitor cell proliferation and granulocyte function by microRNA-223. Nature. 2008;451:1125–1129. doi: 10.1038/nature06607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplitt M.G. Feigin A. Tang C., et al. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson's disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns D.B. Alvord W.G. Heller T., et al. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2600–2610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustikova O.S. Schiedlmeier B. Brugman M.H., et al. Cell-intrinsic and vector-related properties cooperate to determine the incidence and consequences of insertional mutagenesis. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1537–1547. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf P. Rusu M. Sheridan R., et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavilio F. Pellegrini G. Ferrari S., et al. Correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1397–1402. doi: 10.1038/nm1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlich U. Navarro S. Zychlinski D., et al. Insertional transformation of hematopoietic cells by self-inactivating lentiviral and gammaretroviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1919–1928. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E. Cesana D. Schmidt M., et al. The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:964–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI37630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R.A. Dudley M.E. Wunderlich J.R., et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M.G. Schmidt M. Schwarzwaelder K., et al. Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat. Med. 2006;12:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D.L. Levine B.L. Kalos M., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada B.K. Geiszt M. Kaldi K., et al. Dual role of phagocytic NADPH oxidase in bacterial killing. Blood. 2004;104:2947–2953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santilli G. Almarza E. Brendel C., et al. Biochemical correction of X-CGD by a novel chimeric promoter regulating high levels of transgene expression in myeloid cells. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:122–132. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger R.A. Modern management of chronic granulomatous disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2008;140:255–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein S. Ott M.G. Schultze-Strasser S., et al. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat. Med. 2010;16:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toscano M.G. Romero Z. Munoz P., et al. Physiological and tissue-specific vectors for treatment of inherited diseases. Gene Ther. 2011;18:117–127. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban C.F. Ermert D. Schmid M., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg J.M. Van Koppen E. Ahlin A., et al. Chronic granulomatous disease: the European experience. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgensinger V. Seger R. Ryan M.D., et al. Signed outside: a surface marker system for transgenic cytoplasmic proteins. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1193–1199. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zychlinski D. Schambach A. Modlich U., et al. Physiological promoters reduce the genotoxic risk of integrating gene vectors. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:718–725. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.