Abstract

Self-inactivating (SIN)-lentiviral vectors have safety and efficacy features that are well suited for transduction of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), but generation of vector at clinical scale has been challenging. Approximately 280 liters of an X-Linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Disorder (SCID-X1) SIN-lentiviral vector in two productions from a stable cell line were concentrated to final titers of 4.5 and 7.2×108 tu/ml. These two clinical preparations and three additional development-scale preparations were evaluated in human CD34+ hematopoietic cells in vitro using colony forming cell (CFU-C) assay and in vivo using the NOD/Lt-scid/IL2Rγnull (NSG) mouse xenotransplant model. A 40-hour transduction protocol using a single vector exposure conferred a mean NSG repopulating cell transduction of 0.23 vector genomes/human genome with a mean myeloid vector copy number of 3.2 vector genomes/human genome. No adverse effects on engraftment were observed from vector treatment. Direct comparison between our SIN-lentiviral vector using a 40-hour protocol and an MFGγc γ-retroviral vector using a five-day protocol demonstrated equivalent NSG repopulating cell transduction efficiency. Clonality survey by linear amplification-mediated polymerase chain reaction (LAM-PCR) with Illumina sequencing revealed common clones in sorted myeloid and lymphoid populations from engrafted mice demonstrating multipotent cell transduction. These vector preparations will be used in two clinical trials for SCID-X1.

Greene and colleagues report that they have successfully produced a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector at a large enough scale for two clinical trials for SCID-X1. They demonstrate that this vector has reproducible transduction efficiency both in vitro and in vivo and that no adverse effects on engraftment were observed in NOD/Lt-scid/IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice.

Introduction

Insertional oncogenesis due to proto-oncogene activation has been observed using murine γ-retroviral vectors in clinical trials, at first only in severe combined immunodeficiency disorder (SCID-X1) SIN-lentiviral vector (Hacein-Bey-Abina et al., 2003; Hacein-Bey-Abina et al., 2008; Howe et al., 2008) but later in other diseases as well (Stein et al., 2010; Fischer et al., 2011). Lentiviral vectors may be intrinsically safer than γ-retroviral vectors (Montini et al., 2006) because of a different insertional profile, which less frequently targets gene regulatory regions and specific proto-oncogenes (Schröder et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2003; Hematti et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2004). Lentiviral vectors have an additional safety advantage in that they can transduce quiescent cells, which allows a shorter ex vivo culture time with lower cytokine doses and may reduce the risk of transformation (Shou et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2010). Lentiviral backbone alone may not be sufficient to prevent all possible genotoxic adverse events however. In a recent trial using lentiviral vector to treat β-thalassemia, a vector insertion was associated with dysregulation of a growth-promoting gene potentially contributing to an apparent clonal expansion in one subject (Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010). Further safety modifications have thus been developed, including the removal of the endogenous long terminal repeat (LTR) promoter/enhancer in self-inactivating (SIN) configuration (Zufferey et al., 1998) coupled to the use of an internal cellular promoter, (Zychlinski et al., 2008; Montini et al., 2009) and the incorporation of insulator elements to block transcriptional activation of neighboring genes originating from within the vector (Evans-Galea et al., 2007; Ryu et al., 2008; Emery, 2011). We have utilized these strategies to create CL204i-EF1α-hγc-OPT, a SIN-lentiviral vector for the treatment of SCID-X1 that incorporates an internal EF1α promoter to drive expression of a human IL-2Rγc codon-optimized cDNA and flanked by the 400 bp version of the chicken β-Globin HS4 insulator (Throm et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010). This vector has demonstrated relative safety and efficacy in preclinical assays (Zhou et al., 2010).

Producing SIN-lentiviral vectors at scales to support clinical trials is an important challenge for the field. While γ-retroviral vectors can be produced by either transient transfection or the generation of stable producer cell lines, lentiviruses require the expression of multiple cytotoxic accessory genes, which makes the generation of producer cells more complicated (Schweizer et al., 2010). Vector production by transient transfection can be limited by lot-to-lot variability and plasmid contamination of the final product, which could lead to expression of viral genes in vivo (Scaramuzza et al., 2012) or to other recombination events (Schweizer et al., 2010). Vector production by stable producer cells is free of helper plasmid contamination and is generated from a quality controlled master cell bank with end of production cells that can be certified to be free of replication competent lentivirus (RCL). Although clinical trials have successfully used transiently produced SIN-lentiviral vector (Cartier et al., 2009; Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010; Merten et al., 2011; Cartier et al., 2012; Scaramuzza et al., 2012), a scalable stable producer cell system would represent a significant improvement in technology. Stable producer cell lines that make high titer lentiviral vector have been generated (Klages et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2001; Ikeda et al., 2003; Ni et al., 2005; Broussau et al., 2008), but none that can both produce SIN genomes and maintain high titer production. Our producer cell line was generated using a concatemer transfection scheme combined with regulated TetOff expression of cytotoxic viral proteins to allow the generation of Vesicular stomatitis Virus G-glycoprotein envelope (VSV-G) pseudotyped lentiviral vector particles with SIN genomes (Throm et al., 2009).

Preclinical studies of human hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transduction require a suitable surrogate assay. The most stringent of these assays employ mouse xenotransplant, in which human HSCs engraft immune deficient mice where they sustainably self-renew and undergo multilineage differentiation (Yahata et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2008). The human CD34+-derived NOD/SCID repopulating cell is a population thought to approximate the human repopulating cell (Larochelle et al., 1996; Bhatia et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1997). We utilized the NOD/Lt-scid/IL2Rγnull (NSG) mouse, an improved strain that supports higher levels of human cell engraftment and differentiation into B-, T-, and NK-cell lineages (Ishikawa et al., 2005; Lepus et al., 2009; McDermott et al., 2010). In these studies, we evaluate the stably produced material in NSG repopulating cells derived from transduced human mobilized peripheral blood and cord blood CD34+ cells. We demonstrate that we have successfully produced an SCID-X1 SIN-lentiviral vector at a large enough scale to support clinical trials, and the vector material generated had reproducible transduction efficiency. We also demonstrate that NSG repopulating cells can be transduced at meaningful levels with this material using a minimal ex vivo protocol.

Materials & Methods

Vector production

From our master cell bank (MCB), a vial of our vector producing stable cell line GPRG-EF1α-hγcOPT was thawed and the cells seeded at approximately 1–2×105 cells/ml in growth media containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT), 2 mM Glutamax (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 ng/ml doxycycline (Clontech, Mountainview, CA). Cells were grown in static culture flasks incubated at 37°C, 95% relative humidity, and 5% CO2 for six to seven passages to obtain enough cells to seed the WAVE Bioreactor. The cells were harvested, counted, and centrifuged at 400× g for 10 min to collect the cells. A Wave Bioreactor 20/50 system (GE Healthcare Bioscience, Somerset, NJ) with a 10-L (for development runs) or 50-L (for production runs) WAVE Cellbag with 100 or 500 g of Fibra-Cel disks, respectively, was inoculated at 2–4×105 cell/ml in 5-L (development runs) or 25-L (production runs) growth media set at 15 rocks per minute at an angle of 7.5 degrees. The culture was maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and pH of 7.2. On days 4 to 5, vector production was induced by washing twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Lonza) and once with DMEM, then adding production media composed of 25 L of DMEM with 10% FBS and 2 mM Glutamax. Media exchange occurred daily for 6 to 8 days with all harvests after day 2 post-induction were collected for further processing, while days 1 to 2 post-induction were discarded.

Harvests were clarified by 1.2 μm prefilter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) followed by 0.45 μm filter (Millipore) and stored at 4°C. Every two days, harvests were pooled, pH adjusted to 8.0, salt concentration adjusted to 400 mM NaCl, and passed through a Mustang Q ion-exchange capsule (Pall, Ann Arbor, MI). The Mustang Q membrane was washed using 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 with 750 mM NaCl. The capsule was then eluted in fractions using 50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 8.0 with 1.5 M NaCl. Vector-containing fractions were pooled and diluted with phosphate buffer pH 7.2 and human serum albumin (HSA; Talecris, West Clayton, NC) was added to a final concentration of 0.1% and stored at 4°C. At the end of production, all elutates were pooled and concentrated approximately 10-fold by diafiltration using a Pellicon-2 mini filter 0.1 m2 with a 500 kDa cutoff (Millipore) two times with PBS. The final concentrate was formulated with HSA to 0.5%, filtered with a 0.22 μm filter, aliquoted to sealed bags, quick frozen on dry-ice, and stored at –80°C. All procedures for vector production were done under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions.

Purification of CD34+ cells

Human mononuclear cells collected from normal donors were purchased from Key Biologics, LLC. (Memphis, TN). The donors, after obtaining written and informed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols, were treated with 5 mcg/kg/day of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) for 5 days followed by leukapheresis on days 5 and 6. The cells from both collections were pooled and then CD34+ cells purified using the clinical scale CliniMACS device (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., Auburn, CA) in the St. Jude Human Applications Laboratory. The CD34+ cells were suspended in X-Vivo 10 media (Lonza) with 1% HSA (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Westlake Village, CA) and either used immediately or suspended in Plasmalyte-148 (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Westlake Village, CA) with 0.5% HSA (Baxter Healthcare Corporation), frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen for future use. CD34+ human umbilical cord blood cells were purchased from StemCell Technologies, Inc. (Vancouver, Canada).

CD34+ cell transduction protocol

CD34+ cells were cultured in X-Vivo 10 media (Lonza) supplemented with 1% HSA (Baxter Healthcare Corporation) and 100 ng/ml of stem cell factor (SCF), thrombopoietin (TPO), and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt-3L) (CellGenix, Freiberg, Germany) in retronectin-coated (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan) 10-cm dishes or VueLife bags (American Fluoroseal, Gaithersburg, MD) for 16 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 at 1×106 cells/ml. The prestimulation media was then removed and fresh culture media was added, which additionally contains 1.35×108 tu/ml vector and 4 mg/ml protamine sulfate (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) representing a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 135, with mock-transduced cells having received protamine sulfate and X-Vivo 10 with 1% HSA in equal volume to the missing vector. This transduction mix was returned to the incubator for 24 hr. Transduced cells were lifted with trypsin (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), washed, resuspended in PBS with 1% HAS, and stored on ice until use.

NSG mouse xenotransplant

NOD/Lt-scid/IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and bred/maintained in the St. Jude Animal Resource Center (ARC) facility in compliance with protocols approved by the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee. Individual 8–12-week-old female mice were used as recipients. On day −1, recipient mice were given 35 mg/kg busulfan (Busulfex, Otsuke Amera Pharmacutical Inc., Rockville, MD) intraperitoneally as conditioning. On day 0, 1×106 human CD34+ cells were injected via the tail vein into recipient mice. Mice were maintained in the ARC facility on normal food and antibiotic-treated water until week 12 as previously published (Kim et al., 2010).

Obtaining in vivo samples

Starting at week 12, recipients were euthanized in cohorts containing at least one animal from the mock group to verify lack of cross contamination, and bone marrow was harvested from femurs using a 19 gu syringe flush. Spleens and thymi may also have been harvested and homogenized using a 70-micron cell strainer (BD Falcon, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Cell homogenate was subjected to red blood cell lysis (BD Pharmlyse, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA); the cells resuspended in Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) with 1% HSA (Baxter Healthcare Corporation); and then labeled with anti-human CD45, and/or CD19, CD33, and CD3 (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA), for 1 hour; and washed, strained, and then purified by fluorescent activated cell sorter (FACS; FACScalibur, BD biosciences, San Jose, CA). CD45+ bone marrow cells are plated in methylcellulose media (Methocult H4034 Optimum, Stem Cell Technologies) for CFU-C assay. Remaining cell populations were lysed to obtain genomic DNA (Qiagen Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Measurement of graft transduction

Cells from the PBS resuspended cell grafts were analyzed prior to their injection into NSG mice and plated in methylcellulose media (Methocult H4034 Optimum, Stem Cell Technologies) at 1–3.3×102 cells/ml in 35-mm dishes. Methylcellulose cultures were incubated in humidified 25-cm dishes at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 10–14 days to result in plates with 100–150 colonies per plate. Individual well-isolated, well-developed colonies were picked with a micropipette under direct observation using an inverted light microscope and placed in 50 ul milipure water. Thirty colonies and 2 noncolony negative control stabs were harvested per transduction arm. The water/cell mixtures were incubated at 95°C for 10 minutes. Four micrograms of proteinase K (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to each lysate. The lysates were then incubated at 55°C for 60 min and then 95°C for another 10 min. The lysates were then stored at −20°C.

Measurement of NSG repopulating cell transduction

Genomic DNA was isolated from transplanted NSG bone marrow sorted for human CD45+ by FACS using the QIAquick Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). This DNA was assayed using a quantitative real-time PCR assay (RTQ-PCR) with a specific TaqMan (TaqMan Universal PCR Mastermix, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) primer/probe set targeting the 3′ codon optimized human IL2-Rγc/vector backbone junction compared to a proprietary RNaseP reference gene primer/probe set (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) using an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus. To generate the quantitative values, a 0.1 ng to 100 ng standard curve was generated using a Jurkat-derived cell line with a single vector insertion as template. All template DNAs were run in triplicate with the final value representing the mean of the three measurements. Additional controls run with each assay plate included a separate preparation of a different Jurkat single vector insertion cell line, which demonstrated signal for both vector and RNaseP and gave the expected copy number of 1.0±0.2 vector genome per cell and a mock-transduced control, which demonstrated an RNaseP signal but no detectable vector signal (any mock signal higher than water was discarded and repeated with fresh reagents). Any variance of the single copy control that was within assay tolerance but not equal to 1.0 was used to normalize the measurements made in the experimental samples to obtain a normalized vector copy number (VCN) for each DNA template.

Measurement of myeloid vector copy number

Bone marrow was harvested from transplanted NSG mice and sorted for human CD45+ (BD biosciences) expression using FACS (FACScalibur, BD biosciences). Cells were plated in methylcellulose media (Methocult H4034 Optimum, Stem Cell Technologies), cultured, and harvested as per our CFU-C assay protocol outlined above. Colony lysate was used as template for standard PCR reactions with vector-specific and human control gene (RNaseP)–specific primers and 5-Prime Master Mix (5-Prime, Gaithersburg, MD) in a PTC-200 Thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) for 35 cycles. A dilute single vector copy Jurkat clone was used as positive control and water was used as negative control. The reaction mixture was then analyzed by gel electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel. Lysates with both vector and RNaseP bands were scored as positive, RNaseP alone as negative, and no bands as not scorable. Lysates that were vector positive were tested for VCN using the RTQ-PCR assay outlined above. A random selection of vector-negative colony lysates were used for negative controls.

Clonality assessment by linear amplification-mediated polymerase chain reaction

Linear amplification-mediated polymerase chain reaction (LAM-PCR) was performed as published (Schmidt et al., 2007), with the following modifications for our vector. One hundred cycles of linear PCR was performed with biotinylated primer at an annealing temperature of 61°C in 5-Prime Master Mix (5-Prime). Biotinylated product was immobilized on M-270 strepavadin Dynobeads (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY); ligatable ends were created with CviA1I, CviQI, and Tsp509I (NE Biolabs, Ipswich, MA); and ligated to linker sequences using Takara Ligase (Takara Bio). Nested PCR was performed on ligation products with 5-Prime Master Mix. LAM-PCR products were purified using a MinElute PCR clean-up kit (Qiagen) for Illumina sequencing.

Illumina solera sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

First-pass Illumina data for single-end reads obtained in fastq format were initially checked for base-quality values. A custom perl script was written to do regular expression matching, tossing of LTR subsequence, and tagging the vector LTR/human genomic junction. A minimum 30 bp sequence between primer and the end of LTR with no mismatch significantly increased the specificity of finding LTR-derived reads. Reads with no LTR were reconfirmed with Blast against the LTR sequence. No false negative hits were found. A 3-bp wobble at the LTR junction was removed from all samples, and reads shorter than 30 bp were discarded. LTR-derived reads were then subjected to tossing of linker subsequences specific to CviAII, CviQI, and Tsp509I restriction enzymes using a modified linker clipping perl script. Reads having at least 22-bp-long linker and mapping without a mismatch were subjected to clipping. All LTR-only and LTR- and linker-derived reads were pooled for each sample and filtered again to discard reads shorter than 30 bp. Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) was used with default parameters to map against a reference human (hg19, GRCh37, February 2009 assembly) genome downloaded from University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) in fastA format with output in sequence alignment and mapping (SAM) format. Mapped reads were filtered for unique mapping to a locus either by using XT:U tag and/or mapped using the highest map quality (MapQ) of 37. Identified vector insertion sites (VIS) within 10-bp range were merged. Any unique VIS present in five or more reads was kept for final analysis. Human oncogenes present in the dataset were identified using the Cancer Gene Census project website of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

Results

Generation of the CL204i-EF1α-hγc-OPT SIN-lentiviral vector in a WAVE bioreactor

A high titer producer clone for the CL204i-EF1α-hγc-OPT vector (Throm et al., 2009) was expanded to generate a master cell bank (MCB) in our GMP facility. We developed a method to produce clinical trial–scale vector preparations using the WAVE Bioreactor, a sealed production system using a disposable bioreactor chamber containing suspended Fibra-Cel discs for cell adherence.(GE Healthcare Bioscience BioProcess Corp. 2012) Vector production was suppressed in the presence of doxycycline using TetOff regulatory elements. MCB cells were expanded first in flask culture and then in the WAVE in doxycycline-containing media. Once the producer cells reached adequate density, vector production was induced by exchanging the doxycycline-containing media with doxycycline-free media (day 0). Supernatants were harvested every 24 hr by media exchange.

Vector production peaked 48 hr after induction (day 2) and continued until day 5. Vector preparations were titered by flow cytometry for IL2-Rγc expression on ED7R cells, a lymphoid cell line that lacks endogenous IL2-Rγc expression. Titers of unconcentrated supernatant were 1–2×107 transducing units per milliliter (tu/ml) once peak production was achieved (Fig. 1a). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not require testing of this final material for residual doxycyline. We performed three development-scale productions at 5 L/day (Wave6, 7, 8) and two clinical scale productions at 25 L/day (Wave9 and 12). Supernatants were filtered, purified using a Mustang Q ion exchange column, and concentrated approximately 10-fold by tangential flow filtration. The final yields for the clinical scale runs were roughly 30%, with titers of these final products ranging from 4.5–7.2×108 tu/ml (Fig. 1b). Cell density could not be measured directly in the WAVE because the producer cells were adhered to the Fibra-Cel discs, so serial measurements of glucose consumption was used to indicate cell density. The production kinetics of Wave8 were notable for a long plateau, which led to a higher final titer. Wave8 had a lower rate of glucose consumption at the time of induction compared to the other lots, implying that this plateau could have resulted from a lower cell density at the time of induction. To prove we could replicate a clinical-scale production, we produced the Wave12 lot, which we induced not based on time since seeding, but when glucose consumption reached the level at which Wave8 was induced, 1 to 2 grams per liter per day. The production kinetics for Wave12 were improved with a particle production more than double that of Wave9.

FIG. 1.

Vector production from stable cell line using a WAVE bioreactor. (a) Kinetics of vector particle production for three development and two clinical scale runs after induction by media exchange to doxycycline-free D10. Daily harvests from day 3 to end of run were included in final product. Vector positivity was determined by IL-2Rγc surface expression of transduced ED7R cells analyzed by flow cytometry compared to untransduced control. (b) Characteristics of the two clinical scale runs, Wave9 and Wave12. Final titers were determined using the same ED7R method.

Defining conditions for transducing human CD34+ cells by in vitro assay

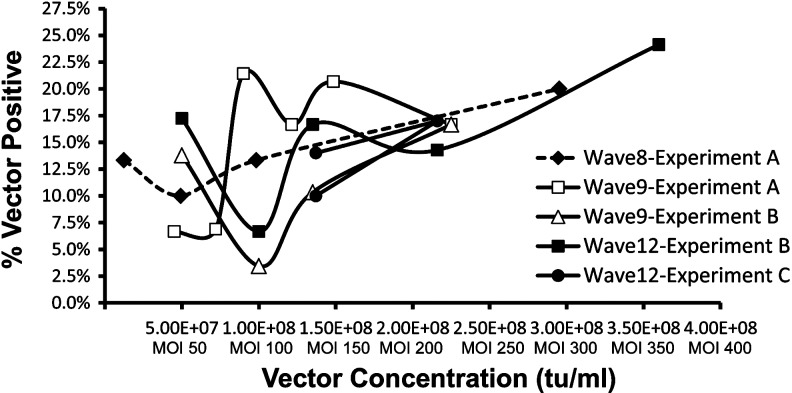

To define a suitable protocol for transduction of CD34+ cells derived from normal human donor G-CSF–mobilized peripheral blood (mPB), varying concentrations of vector were used in titering experiments. Using a short transduction protocol consisting of a 16-hour prestimulation followed by a single 24-hour vector exposure, vector doses greater than 1×108 tu/ml (MOI 100) achieved 10–20% CFU-C transduction with all vector preparations as measured by qualitative PCR of individual colony lysates (Fig. 2). Increasing doses beyond 1×108 tu/ml resulted in only modest increases in transduction efficiency. At doses less than 1×108 tu/ml, transduction efficiency was less consistent (Fig. 2). A vector dose of 1.35×108 tu/ml gave adequate transduction with all vector preparations and was therefore chosen as our working dose. All transductions were performed using our standard culture conditions as described below.

FIG. 2.

Performance of large-scale vector products using human G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells in in vitro transduction assay. Measurement of CD34+ transduction by in vitro CFU-C assay. Experiments with the same letter name performed simultaneously. Each point represents a transduction assayed by qualitative PCR of 30 individual colonies.

Transduction of human CD34+ cells does not affect engraftment in transplanted NSG recipients

We evaluated our 40-hour transduction protocol using an adaptation of the NSG mouse xenotransplant model (Kim et al., 2010) (Fig. 3). Human mPB CD34+ cells were prestimulated overnight in cytokine-containing media beginning on day −2 of transplant. On day −1 of transplant, female NSG mice were conditioned with busulfan 35 mg/kg IP and cells exposed to vector for 24 hr. On day 0, the cells were harvested and transplanted at 1×106 cells per mouse via tail vein injection. After 12 or more weeks post-transplant, animals were humanely killed and bone marrow was analyzed for expression of human CD45 by flow cytometry (Fig. 4a). A mean of 23% human engraftment was observed in all mice, with no difference between vector-treated and mock-treated grafts (Fig. 4b). The myeloid (CD33) and lymphoid (CD19/3) populations within the CD45+ cells in each mouse bone marrow (Fig. 4c) did not differ between vector and mock-treated grafts (Fig. 4d). Treatment with stably produced vector using our 40-hr transduction protocol resulted in maintenance of repopulating activity and lack of lineage skewing.

FIG. 3.

Transduction protocol and experimental outline. This diagram shows the timeline in boxes on the left and sequence of procedures for transplant in boxes in the center for the assays used in this manuscript. Cell, cytokine, and vector doses are indicated, as is culture media for our standard 40-hour transduction protocol. Donor selection and conditioning regimen is also noted.

FIG. 4.

Engraftment characteristics of vector and mock-transduced human G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells obtained from whole bone marrow harvested from NSG recipient mice 12–16 weeks post-transplant. (a) Representative flow cytometry of single mouse bone marrow. (b) Isotype control is shown at left. Human CD45 engraftment comparison of all mock-treated to all vector-treated NSG recipients. Each point represents the result of one mouse's terminal bone marrow evaluation. (c) Representative flow cytometry of human CD45+ fraction for expression of human myeloid (CD33) and lymphoid (CD19/3) markers. (d) Human lineage-specific engraftment comparison of all mock-treated to all vector-treated NSG recipients. Each point represents the result of one mouse's terminal bone marrow evaluation. Bars represent the mean.

Stably produced vector preparations transduce NSG repopulating cells derived from human mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells

To measure transduction efficiency with CL204i-EF1α-hγc-OPT, we developed a quantitative real-time PCR assay (RTQ-PCR) using a vector-specific primer/probe set targeting the junction between the 3′ end of the IL2-Rγc cDNA and the vector backbone, which was compared to a human specific RNaseP reference gene primer/probe set (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Material available online at www.liebertonline.com/hgtb). No signal for either vector or reference gene was detected in untransplanted NSG mice (data not shown). Bone marrow from transplanted NSG mice at 12 or more weeks post-transplant were FACS sorted for human CD45+ cells from which genomic DNA was obtained. Each vector preparation was tested with the 40-hour transduction protocol in a minimum of two to three separate experiments of six to ten NSG each, except Wave12, which was tested in a single experiment using four different transduction protocols. Using this protocol in six different mPB CD34+ cell grafts resulted in a mean NSG repopulating cell transduction efficiency ranging from 0.15–0.25 vector genomes/human genome (Fig. 5a) with no difference in transduction either between individual preparations or between production scales (development lots vs. clinical lots).

FIG. 5.

Transduction of human CD34+-derived NSG repopulating cells with large-scale vector preparations. (a) Transduction efficiency as measured in genomic DNA from FACS-purified human CD45+ bone marrow obtained 12–16 weeks post-transplant using quantitative real-time PCR assay. Each data point represents the result of a single mouse. Number of separate experiments performed with each vector preparation is indicated below the X-axis. Bars represent mean. (b) Myeloid vector copy number measured by quantitative real-time PCR on individual vector-positive colonies obtained from CFU-C assay performed on human CD45+ cells FACS-purified from the bone marrow of NSG mice 12–16 weeks post-transplant. There was no significant difference between arms in any intradonor comparison (not including Donor6-Wave9 because n=1 and thus not evaluable by t-test/ANOVA). The bars represent the mean of all evaluable colonies from all evaluable mice treated in one arm or one experiment. Error bars represent the mean±SEM. Number of evaluated colonies indicated as n.

To evaluate the effect of performing transductions using the closed bags we will use in our clinical trial, the transductions for donor 4 were performed using both 10-cm plates and bags. There was no effect on engraftment or transduction (data not shown), so all further experiments were performed using either one or the other method in all arms. Sorted CD45+ cell populations from engrafted mice were plated in methylcellulose media for CFU-C assay. Individual, well-isolated colonies were plucked from which lysates were prepared. The vector copy number (VCN) as measured in all positive colonies obtained from each experiment demonstrated a distribution around a mean of 3.2 vector genomes/human genome (Fig. 5b). Interdonor variability was observed, with donor 6 being more refractory to transduction while donor 4 was more permissive, but intradonor variability between different vector preparations was not observed.

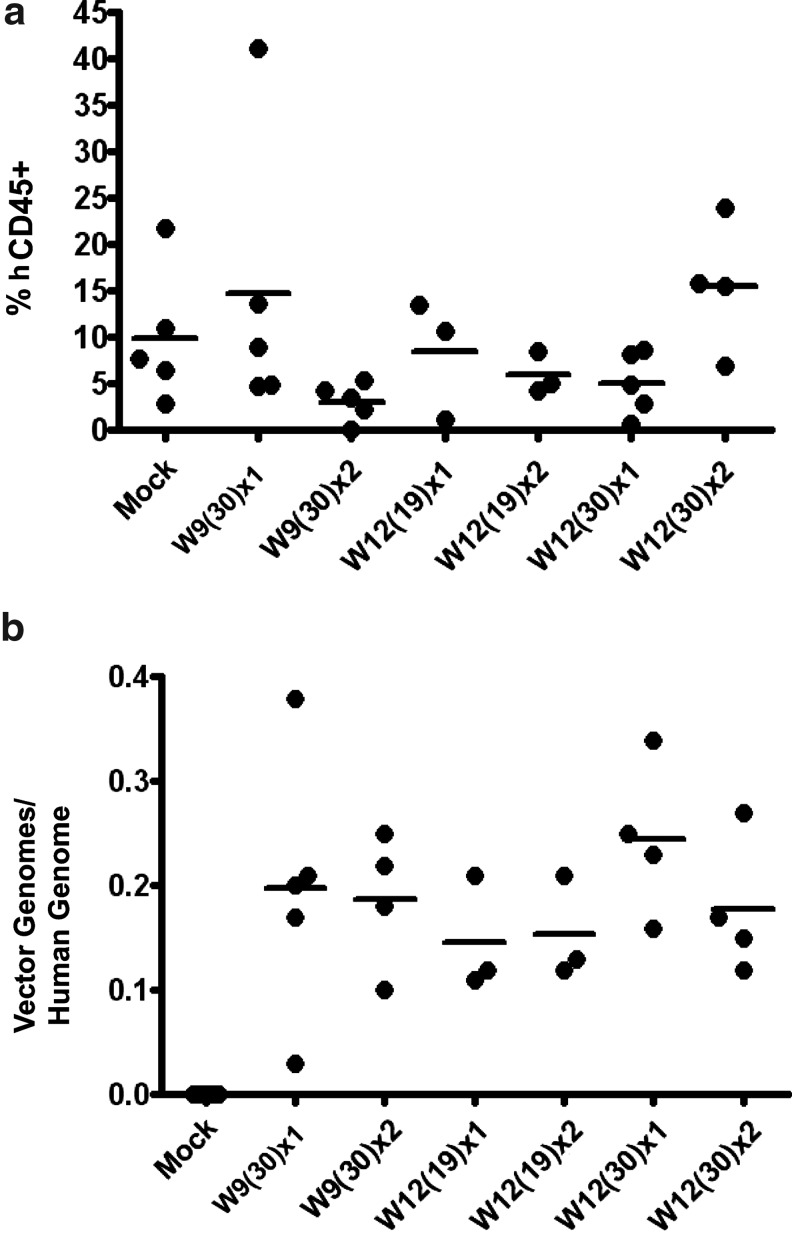

Defining conditions for transducing human CD34+ NSG repopulating cells

The Wave9 preparation was tested using our standard 40-hour protocol and a higher dose protocol employing a second vector exposure for an additional 24 hr in culture. As Wave12 had a higher titer than Wave9, we were able to transduce at the same vector concentration (1.35×108 tu/ml at 19% volume, MOI 135) and the same percent volume at a higher vector concentration (2.25×108 tu/ml at 30% volume, MOI 225), with both doses additionally tested with a second 24-hr exposure arm. Transduced cells were transplanted into NSG mice and analyzed 12 or more weeks post-transplant. We observed no differences in engraftment with any treatment protocol (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. S2) and a mean transduction for all arms of approximately 0.2 vector genomes/human genome with no increase from a second vector exposure (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Fig. S2). For mice that had evaluable bone marrow–derived CFU-C, the myeloid VCN was not different between arms (data not shown), again demonstrating saturation with a single vector exposure of 1.35×108 tu/ml (MOI 135).

FIG. 6.

Transduction of human CD34+-derived NSG repopulating cells with large-scale vector preparations at higher doses. (a) Engraftment of CD34+ transductions in NSG mice measured 12–15 weeks post-transplant. Each point represents the result from a single mouse bone marrow evaluated by flow cytometry. Bars represent the mean. (b) Transduction of NSG repopulating cells measured 12–15 weeks post-transplant. Each point represents the result of a quantitative real-time PCR assay of genomic DNA purified from human CD45+ FACS-sorted bone marrow from a single transplanted NSG mouse. Bars represent the mean. W9(30), Wave9 at 30% volume (MOI 135); W12(19), Wave12 at 19% volume (MOI 135); W12(30), Wave12 at 30% volume (MOI 225); x1, single 24-hr vector exposure; x2, two 24-hr vector exposures.

Comparison of clinical SIN-lentiviral vector preparation to a stably produced γ-retroviral vector

Using both mPB and cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells, we compared the Wave9 preparation to the Gibbon Ape Leukemia Virus (GALV) pseudotyped γ-retroviral MFGγc vector, which was used successfully in the UK trial (Gaspar et al., 2004). The MFGγc vector, which was generated from a producer cell clone at small scale, was used in a longer five-day transduction protocol with higher cytokine doses as reported in the associated clinical trial (Fig. 7a). The Wave9 preparation was used in our standard 40-hour transduction protocol (Fig. 7a). CFU-C analysis of each pre-transplant graft revealed no decrease in colony number to suggest vector toxicity (data not shown) with the MFGγc vector having higher graft transduction in both mPB and CB (Fig. 7b). Analysis of engrafted CD45+ cells 12–16 weeks post-transplant revealed equivalent bone marrow engraftment with both vectors in the mPB arms and decreased engraftment in CB transduced with MFGγc (Fig. 7c). The cord blood CD34+ cells had higher levels of engraftment than mPB, despite using fewer input cells (5×105 cells/NSG recipient for CB vs. 1×106 for mPB). RTQ-PCR analysis of CD45+-sorted populations revealed no difference in transduction efficiency between Wave9 or MFGγc in either mPB or CB (Fig. 7d). This suggests that the Wave9 clinical-scale preparation using a 40-hour transduction protocol can achieve the same NSG repopulating cell transduction efficiency of a laboratory-scale MFGγc preparation using a five-day transduction protocol. A complete set of engraftment and transduction data can be found in Supplementary Figure 3.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of human CD34+ cell transduction with Wave9 clinical SIN-lentivirus prep and an MFGγc gamma-retroviral prep. (a) Transduction protocol outline used for each vector. (b) Pre-transplant CFU-C graft transduction measured in individual colonies by qualitative PCR. There was a significant difference between the Wave9 and MFGγc arms in both mPB and CB. *indicates which comparisons are statistically significant (p<0.05) (c) Human CD45 engraftment of NSG recipients with all treatment arms. Each point represents the result of one mouse's terminal bone marrow evaluation. Bars represent the mean. (d) Transduction of human cord blood and mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells treated with either Wave9 clinical lentiviral preparation or MFGγc γ-retroviral preparation as measured by quantitative real-time PCR in genomic DNA from FACS-purified human CD45+ bone marrow obtained after 12–16 weeks post-transplant. Each data point represents the result of a single mouse. Bars represent the mean.

Clonality survey reveals polyclonal reconstitution and common vector insertions in both lymphoid and myeloid populations

CD45+ bone marrow or spleen cells were sorted by flow cytometry to isolate human myeloid (CD45+/33+/19-) and lymphoid cells (CD45+/33-/19+). Genomic DNA from the sorted cells of five engrafted mice (three vector treated and two mock treated) was subjected to LAM-PCR (Schmidt et al., 2007) to recover VIS. LAM amplicons were analyzed by Illumina sequencing using manufacturer protocol for adapter ligation and barcoded indexing primer addition. Reads were filtered to include full-length LTR sequence without mismatch (30 bp) and unambiguous mapping to the human genome using the BWA algorithm. Any VIS found in the mock-transduced population after filtering were subtracted such that our final experimental set consisted of 21,296,165,864, and 159,202 usable reads mapping to 82, 38, and 27 VIS, respectively. This final set was polyclonal with two of the three vector-treated mice demonstrating VIS common to both myeloid and lymphoid cells (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). No insertions in LMO2, PRDM16, MDS/EVI1, BMI1, CCND2, or HMG2A were observed. A complete list of sequencing results can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Assessment of Clonality of Vector-Transduced Human CD45/Lin+ Cells Obtained from the Bone Marrow of NSG Mice 12–16 Weeks Post-transplant by LAM-PCR

|

Discussion

Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy has resulted in clinical successes, yet the ability to extend this approach to larger clinical trials is limited by vector manufacturing capacity. Our scalable, stable SIN-lentiviral vector production platform compares favorably to HIV-1–based stable producer lines (Klages et al. 2000; Xu et al. 2001; Ikeda et al. 2003; Ni et al., 2005; Broussau et al., 2008), with our system uniquely maintaining production of a SIN vector genome at high titer. The unconcentrated titer generated by our platform also compares favorably to transient production, but with our method achieving a higher yield per production lot due to the large harvest volume with more harvests per lot (Schweizer et al. 2010). Our greater production capacity will also allow more uniform clinical evaluation over greater numbers of patients by not requiring repeated production of vector with every few patients. While transient production can be used to generate vector product at clinical-scale and grade, lot-to-lot variation remains a problem (Schweizer et al. 2010; Merten et al., 2011). We have demonstrated our production method provides vector product that gives reproducible transduction efficiency.

The use of human CD34+-derived NSG repopulating cells is a stringent and relevant preclinical assay for lentiviral vector transduction. Comparison of our transduction results with those that have been previously published is complicated by the use of different endpoint assays on different cell populations. Head-to-head comparison of our Wave9 preparation with MFGγc demonstrated not only equivalent repopulating cell transduction, but that the measurement of graft transduction prior to transplant gave misleadingly favorable results with the γ-retroviral vector. Our transduction results also compare favorably with published lentiviral trials targeting CD34+ cells for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD)(Cartier et al., 2009; Cartier et al., 2012), β-Thalassemia (Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010), and Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (WAS) (Merten et al., 2011; Scaramuzza et al., 2012). The two ALD trial subjects had roughly 0.2 vector genomes/human genome in bone marrow CD34+ cells by RTQ-PCR at 12 months and the β-Thalassemia trial subject (P2), clonal imbalance notwithstanding, had 0.14 vector genomes/human genome in whole bone marrow cells by RTQ-PCR at 24 months. These results are similar to our human CD45+ bone marrow transduction means of 0.13 and 0.15 vector genomes/human genome by RTQ-PCR for Wave9 and Wave12, respectively, in NSG mice. The large-scale transiently produced SIN-vector for WAS (Merten et al., 2011) was evaluated in CB CD34+ cell cultures at 8 days post-transduction with 1×108 tu/ml vector particles and associated with transduction efficiencies of 1.1 and 0.3 vector copies per human genome using RTQ-PCR. This in vitro data compares well to our pre-transplant 41% graft CFU-C transduction and our in vivo results of 0.18, 0.20, and 0.65 vector genomes/human genome.

Lentiviral vectors can potentially cause clonal imbalance in human subjects (Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010) and leukemia in animal models (Montini et al., 2009), suggesting the need to limit the vector copy number. For a measurement of transduction efficiency to represent the average vector copy number in a population of cells, it must be measured in a population where all the cells contain vector. Because only transduced CD34+ cells give rise to mature T-cells in SCID-X1 subjects, VCN can be measured in subject peripheral blood T-cells. The French (Hacein-Bey-Abina et al., 2010) and the United Kingdom (Gaspar et al., 2004; Gaspar et al., 2011) γ-retroviral trials reported a peripheral blood T-cell VCN of about one vector genome/human genome. This implies that clinical success can be achieved even at limiting dose. Using a GFP-expressing lentiviral vector, two stably engrafted rhesus macaques demonstrated 10% and 14% peripheral blood marking with a VCN of 2–3 and 1–2, respectively, in the GFP+ cell fraction (Kim et al., 2009). Transduction of human CB cells treated with two different GFP lentiviral vectors evaluated in NOD/SCID xenotransplants ranged from 1.6–16% with a mean VCN of 3.7 and 4–8% with a mean VCN of 3.9 in the GFP+ populations (Woods et al., 2003). In our studies, we measured VCN in vector-positive clonal populations taken from CFU-C assay plates. Using this approach, we obtained a mean myeloid VCN of 3.2, a value that is similar to VCN reported above.

Using our 40-hour transduction protocol, we found no decrease in engraftment with any of our vector preparations demonstrating a lack of repopulating cell toxicity. In a recent publication (Uchida et al., 2011), the number of engraftable cells was reduced by cell culture longer than 48 hr, the use of IL-3 or IL-6, or cytokine doses higher than the 100/100/100 cocktail. The 40-hour transduction protocol we use includes none of these adverse variables. This is likely relevant since our infant SCID-X1 subjects will not receive a conditioning regimen to facilitate engraftment. Time in culture has been demonstrated to impact the risk of clonal imbalance and leukemia (Shou et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2010), so our 40-hour protocol may represent a further safety advantage. Using multiple vector exposures did not improve NGS repopulating cell transduction with our vector, suggesting that the transduction of CD34+ cells can saturate with continuous exposure to vector preparations. Some groups have also reported this (Uchida et al., 2011), but other groups have found a second vector exposure can increase transduction efficiency (Scaramuzza et al., 2012). The difference between these outcomes could be explained by the protocol that resulted in additive transduction had uniquely incorporated a 12-hour wash/rest phase after the first exposure. This rest phase may function to alleviate saturation, allowing the cells to again become permissive to transduction with the second vector exposure. This wash/rest approach is currently being evaluated with our vector.

The source of CD34+ cells used for transduction also had a significant impact on results. We showed that both the transduction and engraftability of CB cells were greater than mPB cells. While the HSC target population for infant SCID-X1 may be closer in physiology to a CB CD34+ cell than an adult mPB CD34+ cell, we showed that our vector gives similar transduction to a proven standard regardless of cell source. The mPB CD34+ cells obtained from older SCID-X1 subjects have been observed to be more refractory to transduction (Thrasher et al., 2005; Chinen et al., 2007). We transduced 5×106 CD34+ cells derived from a frozen mPB product from one of these older subjects in a 10-cm dish with Wave9 and transplanted five mice. Two survived to 16 weeks for evaluation, which had 0.02 and 0.09 vector genomes/human genome in the CD45+ bone marrow (vs. 0.05 mean in the wild-type mPB control arm) and 0.11 and 0.28 in the spleens (compared to 0.32 mean in the wild-type mPB control arm). While these two mice were too few to draw any strong conclusions, the result is suggestive that older children's cells will be amenable to transduction with our clinical vector preparations.

In summary, we have produced GMP-grade SIN-lentiviral vector for SCID-X1 at clinical scale using a stable producer system. These vector preparations have demonstrated preclinical efficacy using a 40-hour transduction protocol designed to enhance safety and reduce target cell toxicity. The Wave9 and 12 vector preparations described here have passed quality control evaluations and will be used in two clinical gene transfer trials for SCID-X1: LVXSCID-ND, for newly diagnosed infants, which is currently open for enrollment, and LVXSCID-OC, for older children, which will be opening soon. These will be the first human trials to use a stably produced lentiviral vector.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Adrian Thrasher (Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Trust, London, UK) for the generous gifts of the ED7R cell line and the MFGγc producer cell line, Susan Sleep (Children's GMP, LLC, Memphis, TN) for the ED7R titrations and quality control analysis of the clinical preparations, Harry Malech (NIAID-NIH) for the generous gift of the adolescent SCID-X1 mPB, the ARC for assistance in the care and maintenance of the NSG colony, the Flow Cytometry Core Facility for performing all of the flow analysis in this manuscript, and the Hartwell Center Genomic Sequencing Core for the Illumina sequencing and assistance in tailoring the platform for LAM-PCR. This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (grant 5P01HL05374917), the Assisi Foundation of Memphis, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

MRG performed the transductions, transplants, and cell and molecular assays; designed the experiments and assays for measuring transduction and clonality; and authored this manuscript. TL performed the GMP vector productions and optimized the scale-up processing. PKM performed the bioinformatic analysis of the illumina data, designing and optimizing the pipeline as it progressed. YSK established the NSG model at our institution, maintained the colony, and assisted with IP and IV injections. PWE performed all CD34 purifications and sealed-bag transductions. JTG oversaw the derivation of the original producer cell line, the column purification procedure, and generation of the MFGγc vector prep from the stable producer cell line. BPS supervised the work of MRG and JTG and the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

All of the authors of this manuscript declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- Bhatia M. Wang J.C. Kapp U., et al. Purification of primitive human hematopoietic cells capable of repopulating immune-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:5320–5325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussau S. Jabbour N. Lachapelle G., et al. Inducible packaging cells for large-scale production of lentiviral vectors in serum-free suspension culture. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:500–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier N. Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Bartholomae C.C., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier N. Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Bartholomae C.C., et al. Lentiviral hematopoietic cell gene therapy for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Methods Enzymol. 2012;507:187–198. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386509-0.00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M. Payen E. Negre O., et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human β-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinen J. Davis J. De Ravin S.S. Hay B.N., et al. Gene therapy improves immune function in preadolescents with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Blood. 2007;110:67–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery D.W. The use of chromatin insulators to improve the expression and safety of integrating gene transfer vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2011;22:761–74. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Galea M.V. Wielgosz M.M. Hanawa H., et al. Suppression of clonal dominance in cultured human lymphoid cells by addition of the cHS4 insulator to a lentiviral vector. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:801–809. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A. Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Cavazzana-Calvo M. Gene therapy for primary adaptive immune deficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1356–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar H.B. Parsley K.L. Howe S., et al. Gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by use of a pseudotyped gammaretroviral vector. Lancet. 2004;364:2181–2187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar H.B. Cooray S. Gilmour K.C., et al. Long-term persistence of a polyclonal T cell repertoire after gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:97ra79. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GE Healthcare. 2008. WAVE Bioreactor 2/10 Operator Manual 87-4500-23 AH 11.

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Von Kalle C. Schmidt M., et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Garrigue A. Wang G.P., et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3132–3142. doi: 10.1172/JCI35700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Hauer J. Lim , et al. Efficacy of gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:355–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hematti P. Hong B.K. Ferguson C., et al. Distinct genomic integration of MLV and SIV vectors in primate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe S.J. Mansour M.R. Schwarzwaelder K., et al. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3143–3150. doi: 10.1172/JCI35798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y. Takeuchi Y. Martin F., et al. Continuous high-titer HIV-1 vector production. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:569–572. doi: 10.1038/nbt815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa F. Yasukawa M. Lyons B., et al. Development of functional human blood and immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2 receptor {gamma} chain(null) mice. Blood. 2005;106:1565–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Kobayashi K. Nakahata T. NOD/Shi-scid IL2rgamma(null) (NOG) mice more appropriate for humanized mouse models. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;324:53–76. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75647-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.J. Kim Y.S. Larochelle A., et al. Sustained high-level polyclonal hematopoietic marking and transgene expression 4 years after autologous transplantation of rhesus macaques with SIV lentiviral vector-transduced CD34+ cells. Blood. 2009;113:5434–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-185199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.S. Wielgosz M.M. Hargrove P., et al. Transduction of human primitive repopulating hematopoietic cells with lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with various envelope proteins. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1310–1317. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klages N. Zufferey R. Trono D. A stable system for the high-titer production of multiply attenuated lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2000;2:170–176. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle A. Vormoor J. Hanenberg H., et al. Identification of primitive human hematopoietic cells capable of repopulating NOD/SCID mouse bone marrow: implications for gene therapy. Nat Med. 1996;2(12):1329–37. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepus C.M. Gibson T.F. Gerber S.A., et al. Comparison of human fetal liver, umbilical cord blood, and adult blood hematopoietic stem cell engraftment in NOD-scid/gammac-/-, Balb/c-Rag1-/-gammac-/-, and C.B-17-scid/bg immunodeficient mice. Hum. Immunol. 2009;70:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott S.P. Eppert K. Lechman E.R., et al. Comparison of human cord blood engraftment between immunocompromised mouse strains. Blood. 2010;116:193–200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-271841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten O.W. Charrier S. Laroudie N., et al. Large-scale manufacture and characterization of a lentiviral vector produced for clinical ex vivo gene therapy application. Hum. Gene Ther. 2011;22:343–56. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R.S. Beitzel B.F. Schroder A.R., et al. Retroviral DNA integration, ASLV, HIV, and MLV show distinct target site preferences. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E. Cesana D. Schmidt M., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene transfer in a tumor-prone mouse model uncovers low genotoxicity of lentiviral vector integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:687–96. doi: 10.1038/nbt1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E. Cesana D. Schmidt M., et al. The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:964–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI37630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y. Sun S. Oparaocha I., et al. Generation of a packaging cell line for prolonged large-scale production of high-titer HIV-1-based lentiviral vector. J. Gene Med. 2005;7:818–834. doi: 10.1002/jgm.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu B.Y. Evans-Galea M.V. Gray J.T., et al. An experimental system for the evaluation of retroviral vector design to diminish the risk for proto-oncogene activation. Blood. 2008;111:1866–1875. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-085506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza S. Biasco L. Ripamonti A., et al. Preclinical Safety and Efficacy of Human CD34(+) Cells Transduced With Lentiviral Vector for the Treatment of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome. Mol. Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.23. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. Schwarzwaelder K. Bartholomae C., et al. High-resolution insertion-site analysis by linear amplification-mediated PCR (LAM-PCR) Nat. Methods. 2007;4:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder A.R. Shinn P. Chen H., et al. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer M. Merten O.W. Large-scale production means for the manufacturing of lentiviral vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2010;10:474–486. doi: 10.2174/156652310793797748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers S. Gomes T.J. Larochelle A., et al. Ex vivo expansion of retrovirally transduced primate CD34+ cells results in overrepresentation of clones with MDS1/EVI1 insertion sites in the myeloid lineage after transplantation. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1633–1639. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou Y. Ma Z. Lu T. Sorrentino B.P. Unique risk factors for insertional mutagenesis in a mouse model of XSCID gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:11730–11735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603635103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein S. Ott M.G. Schultze-Strasser S., et al. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat Med. 2010;16(2):198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher A.J. Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Gaspar H.B., et al. Failure of SCID-X1 gene therapy in older patients. Blood. 2005;105:4255–4257. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throm R.E. Ouma A.A. Zhou S., et al. Efficient construction of producer cell lines for a SIN lentiviral vector for SCID-X1 gene therapy by concatemeric array transfection. Blood. 2009;113:5104–5110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N. Hsieh M.M. Hayakawa J., et al. Optimal conditions for lentiviral transduction of engrafting human CD34+ cells. Gene Ther. 2011;18:1078–1086. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.C. Doedens M. Dick J.E. Primitive human hematopoietic cells are enriched in cord blood compared with adult bone marrow or mobilized peripheral blood as measured by the quantitative in vivo SCID-repopulating cell assay. Blood. 1997;89:3919–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods N.B. Muessig A. Schmidt M., et al. Lentiviral vector transduction of NOD/SCID repopulating cells results in multiple vector integrations per transduced cell: risk of insertional mutagenesis. Blood. 2003;101:1284–1289. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. Li Y. Crise B. Burgess S.M. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science. 2003;300:1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K. Ma H. McCown T.J., et al. Generation of a stable cell line producing high-titer self-inactivating lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2001;3:97–104. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahata T. Yumino S. Seng Y., et al. Clonal analysis of thymus-repopulating cells presents direct evidence for self-renewal division of human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2006;108:2446–2454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S. Mody D. DeRavin S.S., et al. A self-inactivating lentiviral vector for SCID-X1 gene therapy that does not activate LMO2 expression in human T cells. Blood. 2010;116:900–908. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R. Dull T. Mandel R.J., et al. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J. Virol. 1998;72:9873–9880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9873-9880.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zychlinski D. Schambach A. Modlich U., et al. Physiological promoters reduce the genotoxic risk of integrating gene vectors. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:718–725. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.