Abstract

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterised by reduced bone quantity and quality and an increased susceptibility to fracture, and appears to be one of many chronic conditions that might be influenced by events early in life. Specifically, there is growing evidence of an interaction between the genome and the environment in the expression of the disease.

Keywords: osteoporosis, programming, bone, fracture, nutrition, cohort

Introduction

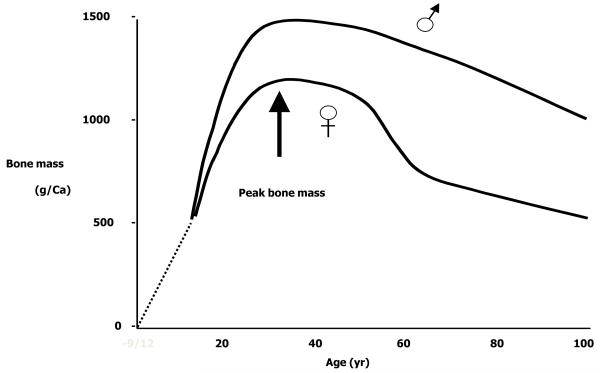

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterised by reduced bone quantity and quality and an increased susceptibility to fracture [1]. It is a very common condition, with the remaining lifetime risk of a fragility fracture estimated at 53.2 % in a UK woman aged 50 [1]. The risk of fracture rises sharply with increasing age in both sexes [1] and depends on two factors: the mechanical strength of bone and the forces applied to it. Mechanical strength is strongly influenced by bone mass; this parameter represents a combination of bone size and volumetric mineral density. It is recognised that the bone mass of an individual in later life (the time at which fragility fractures become common) depends upon the peak attained during skeletal growth and the subsequent rate of bone loss, as demonstrated in Figure 1, so that a higher bone mass, and hence a lower likelihood of fracture, may be achieved through maximising peak bone mass, or by reducing bone loss. The relative contribution of these two processes has recently been elucidated. Hui et al explored the relative contributions of peak bone mass and bone loss to adult bone mass and found that at age 70 years, they each explained 50% of the variance in bone mineral density (BMD) [2]. A more recent modelling study from Hernandez et al demonstrated that peak bone mass was six times more powerful a predictor of age of onset of osteoporosis than age of menopause or rate of bone loss [3].

Figure 1.

Bone mass acquisition through the lifecourse

Optimal peak bone mass acquisition is therefore critical to bone health in later life. The fetus accretes 80% of the required 30g calcium during the last trimester in human pregnancies [4]; thereafter bone mass increases largely as a result of increase in bone size throughout childhood. During the adolescent growth spurt around 25% of the final peak bone mass is achieved [4]. Peak bone mass is reached in the twenties, and but exact timing appears to vary with skeletal site and with sex [4]. After the achievement of peak bone mass, bone density starts to decline and this is accelerated after the menopause in women. We believe that the skeletal growth trajectory becomes set early in life; this is known as “tracking”. Animal studies have attempted to alter this growth trajectory through dietary manipulation, with a consequent effect on skeletal parameters, and will be discussed in more detail later in this review.

Osteoporosis appears to be one of many chronic conditions that might be influenced by events early in life. Specifically, there is growing evidence of an interaction between the genome and the environment in the expression of the disease, with epigenetics playing an increasing role in mechanistic studies. The suggestion that the skeleton can be permanently changed by an adverse early environment is of course not novel - rickets is a very visible example. This article will review the evidence for programming of osteoporosis, highlighting epidemiological studies of BMD and fracture in cohorts where birth details are known, and studies of potential underlying mechanisms.

Intrauterine programming of osteoporosis and fracture

Fracture is the ultimate consequence of osteoporosis and represents the public health burden of the condition. Although there is no absolute threshold that determines whether fracture will, or will not, occur there is a graded risk with an approximate doubling of fracture risk with each standard deviation drop in BMD [5]. Epidemiological studies that have sought to examine relationships between early life factors and osteoporosis have often looked at relationships with BMD rather than fracture, given the large sample sizes required to use fracture as a study outcome until cohorts reached a relatively advanced age.

The first epidemiological evidence that osteoporosis risk might be programmed came from a study of 153 women born in Bath during 1968-69 who were traced and studied at age 21 years [6]. Data on childhood growth were obtained from linked birth and school health records. There were significant associations between weight at one year and bone mineral content (BMC), at the lumbar spine and femoral neck; these relationships were independent of adult weight and body mass index. The study suggested that while early life factors were important in determining the size of the skeletal envelope, mineralisation within that skeletal envelope was strongly influenced by adult lifestyle such as physical activity.

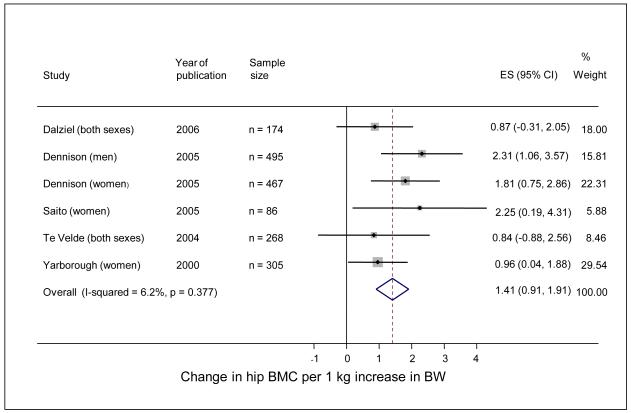

In a second cohort study of 238 men and 201 women aged 60-75 years, who were born and still lived in Hertfordshire [7], there were highly significant relationships between weight at one year and adult bone area at the spine and hip; the relationships with BMC at these two sites were weaker but remained statistically significant. They also remained after adjustment for lifestyle characteristics in adulthood that might have influenced bone mass (physical activity, dietary calcium intake, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption). Similar relationships have now been replicated in a younger Hertfordshire cohort [8]; in this study the relative contributions of birthweight, weight at one year and adult weight to adult bone mass were considered, and it appeared that the contributions of early growth were greatest for bone area, and clearly apparent for BMC, but not as evident for volumetric BMD. The findings of studies performed by other groups also suggest the importance of the early environment in the determination of later bone mass, and have been summarised in a recent systematic review that identified fourteen studies that were eligible for inclusion. Meta-analysis demonstrated that a 1 kg increase in birthweight was associated with a 1.49 g increase in lumbar spine BMC (95% CI 0.77-2.21); birthweight was not associated with lumbar spine BMD in 11 studies. In six studies, considering the relationship between birthweight and hip BMC, meta-analysis demonstrated that a 1 kg increase in birthweight was associated with a 1.41 g increase in hip BMC (95% CI 0.91-1.91)(Figure 2).. Seven studies considered the relationship between birthweight and hip BMD and, in most, birthweight was not a significant predictor of hip BMD. Three studies assessing the relationship between weight at 1 year and adult bone mass all reported that higher weight at one was associated with greater BMC of the lumbar spine and hip [9].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies assessing the association between birthweight (kg) and BMC of the hip in adults (reproduced with permission from [9])

In addition to BMC and BMD, the forces applied to a bone are important in determining fracture risk. These might be modified by bone geometry and for this reason Javaid et al undertook analysis of the DXA scan images acquired in 300 Hertfordshire Cohort Study participants, using automated Hip Structure Analysis to derive estimates of femoral neck length, width, cross-sectional moment of inertia (CSMI) and buckling ratio [10]. Their findings suggested that poor growth in utero and during the first year of postnatal life was associated with disproportion of the proximal femur in later life (narrower neck but preserved axis length), with a corresponding reduction in mechanical strength of the region, over and above that attributable to reduced BMC per se.

In the third detailed analysis of bone density, geometry and strength among participants from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, peripheral computed tomography (pQCT) was utilised to evaluate cortical and trabecular bone density, strength strain index and fracture load in the distal radius and tibia (Stratec XCT2000 instrument) [11]. There were strong associations between birth-weight, conditionally adjusted weight at one year, and each of bone width, length, area, fracture load and strength-strain index, at the tibia among both men and women, with less marked associations in a similar direction for the proximal radius. The relationships were again robust to adjustment for adult lifestyle factors such as age, body mass index, social class, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, dietary calcium intake, and HRT use among women. The data add to those from Hip Structure Analysis and suggest that poor growth in utero and during the first year of postnatal life is associated with alterations in bone architecture, cortical size and geometry, in addition to a deficit in densitometrically measured bone mineral content, resulting in compromised bone strength and increased risk of later fracture. Studies are currently underway to establish relationships between bone strength using the newest and most sophisticated techniques and early life factors.

As we have discussed the clinically important consequence of reduced bone mass is fracture. Data is now available which directly link growth rates in childhood with the risk of later hip fracture [12]. Studies of a unique Finnish cohort in whom birth and childhood growth data were linked to later hospital discharge records for hip fracture, have permitted follow-up of around 7,000 men and women who were born in Helsinki during 1924-1933. Body size at birth was recorded and serial measurements of height and weight throughout childhood were available. Hip fracture incidence was assessed in this cohort using the Finnish hospital discharge registration system. After adjustment for age and sex, there were two major determinants of hip fracture risk: tall maternal height, and low rate of childhood growth, which was statistically independent of each other. Hip fracture risk was also elevated among babies born short, but of average height by age 7 years, suggesting that hip fracture risk might be particularly elevated among children in whom growth of the skeletal envelope is forced ahead of the capacity to mineralise, a phenomenon which is accelerated during pubertal growth. A second paper from this cohort has identified a low BMI in childhood as an important predictor of hip fracture in adulthood, suggesting a direct effect of low fat mass on bone mineralisation, or an influence of altered timing of pubertal maturation [13].

The third piece of epidemiological evidence that osteoporosis might be programmed stems from mother-offspring studies [14]. In the Princess Anne hospital cohort, after adjusting for sex and gestational age at birth, neonatal bone mass was strongly, positively associated with birthweight, birth length and placental weight. Other determinants included maternal and paternal birthweight, and maternal triceps skinfold thickness at 28 weeks. Maternal smoking and energy intake at 18 weeks gestation, were negatively associated with neonatal BMC at both the spine and whole body. More recently paternal skeletal size and areal density have been shown to be positively associated with intrauterine bone mineral accrual but more strongly in female infants [15]. The influence of the father on skeletal development in the offspring is necessarily genetic (for example through the imprinting of growth promoting genes such as IGF-2), in contrast to the combined genetic and environmental influences in the mother.

Javaid et al [16] showed that the same maternal factors that had been associated with neonatal bone mass in both the Princess Anne and Southampton Women’s Survey cohorts were all associated with reduced whole body BMC of the child at age 9 years. In the same study, lower ionised calcium concentration in umbilical venous serum also predicted reduced childhood bone mass; this association appeared to mediate the effects of maternal fat stores, smoking and socioeconomic status on the bone mass of the children at age 9 years. It was also noted that around 31% of the mothers had insufficient and 18% had deficient circulating concentrations of 25(OH)-vitamin D during late pregnancy (11-20 and <11 nmol/l respectively. Reduced concentration of 25(OH)-vitamin D in mothers during late pregnancy was associated with reduced BMC in children at age 9 years and remained robust after adjusting for childhood calcium intake and physical activity, as well as for maternal smoking and body build. Further evidence supporting a role for maternal vitamin D status was obtained in the Southampton Women’s Survey, where maternal vitamin D concentrations again correlated with neonatal bone mass [17], and with the shape of the fetal femur, whereby maternal vitamin D insufficiency was associated with femoral splaying as early as 19 weeks of gestation. These findings have led onto a randomised controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation to pregnant women that will report shortly.

Finally, in recent work looking at postnatal growth, relationships between fetal growth and growth and skeletal indices at 4 years of age were stronger for the first and second postnatal years, than the period aged 2-4 years [18]. The proportion of children changing their place in the distribution of growth velocities progressively reduced with each year of postnatal life. These data suggest a critical time window for determination of the skeletal growth trajectory, with vitamin D a particularly topical potential effector.

Mechanisms of programming

There are three cellular mechanisms for the induction of programming. First, the nutrient environment may permanently alter gene expression; one example of this is permanent change in the activity of metabolic enzymes such as HMG-CoA reductase [19]. Recent studies have highlighted epigenetic phenomena as a mechanism whereby the environment can influence gene expression. One such example in osteoporosis comes from mechanistic work using placental samples from the SWS that has shown that mRNA expression of the key active plasma membrane calcium transporter (PMCA3) is significantly related to bone mass of the newborn offspring [20] consistent with the hypothesis that maternal vitamin D insufficiency might alter placental calcium transport. Epigenetic mechanisms may also underpin the previous reports of interaction between polymorphism in the gene for the vitamin D receptor, birth weight, and bone mineral density in the Hertfordshire cohort, such that among individuals in the lowest third of birth weight, spine BMD was higher among individuals of genotype ‘BB’ after adjustment for age, sex and weight at baseline [21] while in contrast, spine BMD was reduced in individuals of the same genotype who were in the highest third of the birthweight distribution. A similar interaction was observed between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human growth hormone gene (GH1) and weight in infancy, adult bone mass and bone loss rates [22]. This SNP was shown to be functional, and complemented previous work showing relationships between circulating GH and cortisol and bone loss rates in Hertfordshire.

Second, early nutrition may permanently reduce cell numbers. The small, but normally proportioned rat produced by undernutrition before weaning, has been shown to have fewer cells in its organs and tissues. Amman et al investigated the effects of four isocaloric diets with varying levels of protein content on areal BMD, bone ultimate strength, histomorphometry, biochemical markers of bone remodeling, plasma IGF-I, and sex hormone status in adult female rats [23]. After 16 weeks on a low protein diet, BMD was significantly decreased at skeletal sites containing trabecular or cortical bone. Mehta et al also explored the effect of maternal undernutrition using a rat maternal protein deficiency model [24]. They found that offspring of protein restricted mothers had a reduction in bone area, but not BMD, compared to offspring of mothers fed a normal diet during pregnancy. It was also found that the offspring of the protein-restricted mothers had abnormally widened growth plates compared with the offspring of controls. These data complement work that reported that offspring from mothers fed a restricted protein diet during pregnancy had femoral necks with thinner, less dense trabeculae, femoral necks with more closely packed trabeculae, vertebrae with thicker, denser trabeculae and midshaft tibiae with denser cortical bone as assessed my micro-CT [25]. Thus maternal undernourishment appears to modulate skeletal growth in the offspring through alternation of both the osteogenic environment and skeletal structure.

Thirdly, certain clones of cells may be altered by environmental adversity during development; at this time, this mechanism appears less important in skeletal programming.

Conclusions

There is widespread epidemiological evidence suggesting a link between early life events and later risk of osteoporosis. Such studies have been complemented in recent years by animal work showing that maternal undernutrition has a lasting effect on skeletal development in the offspring, and an increasing awareness of the potential role of epigenetic phenomena as a possible mechanism that might mediate the relationship between maternal factors and fetal development. Future work will focus on mechanism of programming, through detailed studies of bone structure and epigenetic work, and will also move forward to interventional work, such as the MAVIDOS study.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Medical Research Council; the Wellcome Trust, the Arthritis Research Campaign; and the National Osteoporosis Society for support of our research programme into the fetal origins of osteoporotic fracture.

Footnotes

Statement of Interest Dr Harvey and Professor Dennison have no conflicts of interest to declare. Professor Cooper has received consulting and lecture fees from AMGEN, GSK, Alliance for Better Bone Health, MSD, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, Servier, Medtronic and Roche.

References

- 1.Dennison E, Cole Z, Cooper C. Diagnosis and epidemiology of osteoporosis. Current Opinions in Rheumatology. 2005;17:456–61. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000166384.80777.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC., Jr. The contribution of bone loss to postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 1990;1:30–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01880413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez CJ, Beaupre GS, Carter DR. A theoretical analysis of the relative influences of peak BMD, age-related bone loss and menopause on the development of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:843–847. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs CS. In: Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. Favus MJ, editor. ASBMR; Washington: 2003. pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ. 1996;312:1254–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper C, Cawley MID, Bhalla A, et al. Childhood growth, physical activity and peak bone mass in women. J Bone Min Res. 1995;10:940–947. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper C, Fall C, Egger P, et al. Growth in infancy and bone mass in later life. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:17–21. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennison EM, Syddall HE, Aihie Sayer A, et al. Birthweight and weight at one year are independent determinants of bone mass in the seventh decade: the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Ped Res. 2005;57:582–6. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000155754.67821.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baird J, Kurshid MA, Kim M, et al. Does birthweight predict bone mass in adulthood? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporosis Int. 2011;22:1323–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javaid MK, Lekamwasam S, Clark J, et al. Infant growth influences proximal femoral geometry in adulthood. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:508–12. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.051214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver H, Jameson K, Aihie Sayer A, et al. Growth in early life predict bone strength in late adulthood: the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Bone. 2007;41:400–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper C, Eriksson JG, Forsén T, et al. Maternal height, childhood growth and risk of hip fracture in later life: a longitudinal study. Osteoporosis Int. 2001;12:623–629. doi: 10.1007/s001980170061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javaid MK, Erikssn JG, Kajantie E, et al. Growth in childhood predicts hip fracture risk in later life. Osteoporosis Int. 2011;22:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfrey K, Walker-Bone K, Robinson S, et al. Neonatal bone mass: influence of parental birthweight, maternal smoking, body composition, and activity during pregnancy. J Bone Min Res. 2001;16:1694–1703. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.9.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Poole JR, et al. Paternal skeletal size predicts intrauterine bone mineral accrual. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1676–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Javaid MK, Crozier SR, Harvey NC, et al. Maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy and childhood bone mass at age 9 years: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2006;367(9504):36–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67922-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ioannou C, Javaid MK, Mahon P, et al. The effect of maternal vitamin D concentration on fetal bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97 doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2538. epub 2012 Sept 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey NC, Mahon PA, Kim M, et al. Intrauterine growth and postnatal skeletal development: findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:34–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown SA, Rogers LK, Dunn JK, et al. Development of cholesterol homeostatic memory in the rat is influenced by maternal diets. Metabolism. 1990;39:468–473. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin R, Harvey NC, Crozier SR, et al. Placental calcium transporter (PMCA3) gene expression predicts intrauterine bone mineral accrual. Bone. 2007;40:1203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennison EM, Arden NK, Keen RW, et al. Birthweight, vitamin D receptor genotype and the programming of osteoporosis. Paed Peri Epidemiol. 2001;15:211–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennison E, Syddall H, Rodriguez S, et al. Polymorphism in the growth hormone gene, weight in infancy and adult bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4898–903. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammann P, Bourrin S, Bonjour JP, et al. Protein undernutrition-induced bone loss is associated with decreased IGF-1 levels and estrogen deficiency. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:683–680. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta G, Roach HI, Langley-Evans S, et al. Intrauterine exposure to a maternal low protein diet reduces adult bone mass and alters growth plate morphology in rats. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2002;71:493–498. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-2104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanham SA, Roberts C, Perry MJ, et al. Intrauterine programming of bone. Part 2: alteration of skeletal structure. Osteopor Int. 2008;19:157–167. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]