Abstract

Many cancer chemotherapeutic agents form DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs), extremely cytotoxic lesions that form covalent bonds between two opposing DNA strands, blocking DNA replication and transcription. However, cellular responses triggered by ICLs can cause resistance in tumor cells, limiting the efficacy of such treatment. Here we discuss recent advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of ICL repair that cause this resistance. The recent development of strategies for the synthesis of site-specific ICLs greatly contributed to these insights. Key features of repair are similar for all ICLs, but there is increasing evidence that the specifics of lesion recognition and synthesis past ICLs by DNA polymerases are dependent upon the structure of ICLs. These new insights provide a basis for the improvement of antitumor therapy by targeting DNA repair pathways that lead to resistance to treatment with crosslinking agents.

Keywords: Interstrand crosslinks, Cancer chemotherapy, DNA repair, Cisplatin, Nitrogen mustards

Introduction

The faster proliferation of cancer cells compared to healthy ones makes cell cycle-dependent DNA metabolism a main target for chemotherapeutic agents. While some agents interfere with chromosome segregation during cell division or with the generation of nucleotide triphosphates needed for DNA synthesis, a large number of drugs used in chemotherapeutic regimens directly target DNA to kill malignant cells [1, 2]. These agents form adducts with DNA that interfere with essential aspects of its metabolism such as DNA replication and transcription, triggering cell death. Among DNA damaging agents, those forming DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs) are particularly potent as ICLs make strand separation impossible by the covalent linkage of two DNA strands [3, 4]. ICLs, like most DNA lesions, trigger cellular signaling and repair cascades that are associated with resistance of tumor cells to ICL-forming agents [5]. Due to the genetic make up of tumor cells and the generally higher mutation rates, the levels of resistance to chemotherapeutic agents vary greatly and present a serious problem in finding optimal therapies.

In this review we will discuss our current understanding of the biological responses triggered by ICLs with a focus on the use of synthetic adducts that have facilitated these studies. We will also provide an outlook into how these findings may be translated into the design of therapeutic agents for cancer chemotherapy.

Bifunctional alkylating agents form ICLs as the physiologically most important lesions

DNA crosslinking agents were among the first chemotherapeutic drugs used to treat cancer in the 1940s, after a serendipitous discovery. Mechlorethamine, a nitrogen mustard, was originally designed as a more stable derivative of mustard gas as a chemical warfare agent. An accident led to the exposure of civilians and soldiers to mustard gas during World War II and revealed the lymphotoxic effect of these agents. Together with earlier observations of mustard gas on cell growth, these observations provided the motivation for the first clinical trials and successful treatment of lymphoma patients with nitrogen mustards (NM) [6–8]. Numerous derivatives of mechlorethamine have subsequently been developed and NMs such as chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, and ifosfamide are still mainstays of antitumor therapy. Only many years later, after the elucidation of the double helical structure of DNA was it established that NMs form ICLs by reacting with the N 7 positions of two guanine residues on two complementary DNA strands [9–11]. ICL formation was subsequently demonstrated for a number of additional antitumor agents, including platinum complexes, mitomycin C, and chloro ethyl nitroso ureas [11, 12]. Crosslinking agents are, however, not limited to cancer chemotherapy and a number of endogenous and environmental agents such malondialdehyde (a lipid peroxidation product), acetaldehyde, and natural products like the furocoumarins (present in plants and cosmetics), can form ICLs [13]. Since such adducts constitute a serious threat to cellular survival, they have provided an evolutionary incentive for organisms to develop the ability to repair ICLs. The importance of these repair pathways is evidenced by the existence of the human cancer-prone disorder Fanconi anemia (FA). Cells from FA patients are specifically sensitive to crosslinking agents, implicating deficient ICL repair as a cause for the genomic instability that leads to carcinogenesis. While these repair pathways are vital for healthy cells, they cause resistance to ICL-forming agents in a therapeutic setting [14, 15].

Generation and structures of ICL-containing DNA

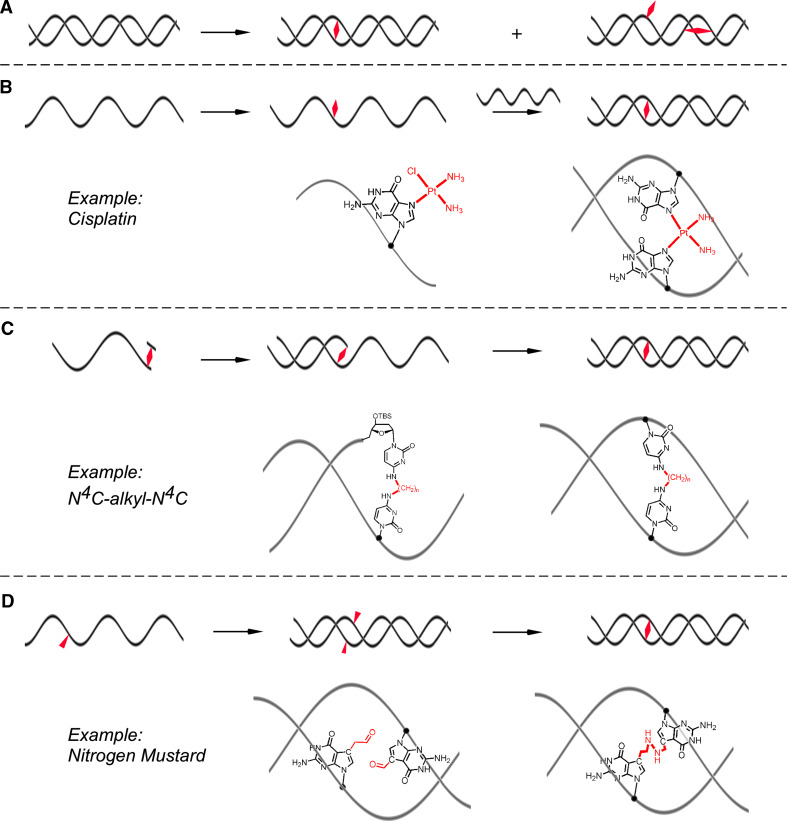

One of the prerequisites for studying ICL repair is the availability of defined ICL-containing oligonucleotides. Initially, this was achieved by the reaction of duplex DNA with crosslinking agents (Fig. 1a). While this approach led to the generation of DNA duplexes with ICLs formed by NM, cisplatin, BCNU, or mitomycin C, it is very inefficient, yielding only about 1–5% of ICL adducts, with monoadducts and intrastrand crosslinks making up the majority of products [3, 4]. This approach can be improved upon to a minor extent by generating first a monoadduct with a single-stranded oligonucleotide, followed by annealing to a complementary strand and ICL formation (Fig. 1b). More targeted strategies for the synthesis of ICLs have recently been developed that make use of site-specific solid-phase DNA synthesis and introduce the ICL either in form of a crosslinked dimer (Fig. 1c) or as ICL precursors that can undergo a specific coupling reaction after incorporation into complementary strands and annealing (Fig. 1d). These approaches are discussed in more detail in conjunction with crosslinking agents and structures of ICL-containing oligonucleotides below.

Fig. 1.

Methods for the preparation of DNA interstrand crosslinks. a Treatment of an oligonucleotide with a bifunctional alkylating agent. This method gives rise to a mixture of products (intra- and interstrand crosslinks, monoadducts) and ICL typically make up less than 5% of all the products. b Two-step ICL formation. After reaction of a single strand containing one guanine residue, the monoadduct is purified, annealed with a complementary strand, and activated to react with the other strand. This method is more efficient than a, but yields typically do not exceed 20%. c Multi-step solid-phase synthesis; the crosslink is chemically synthesized as a nucleotide dimer and incorporated into DNA followed by bidirectional solid-phase DNA synthesis. This approach yields highly specific ICLs. d Two crosslink precursors are incorporated into DNA using solid-phase DNA synthesis and the ICL formed by a selective post-synthetic crosslinking reaction. This approach also yields ICLs with high specificity and in high yields. ICLs are shown as red diamonds

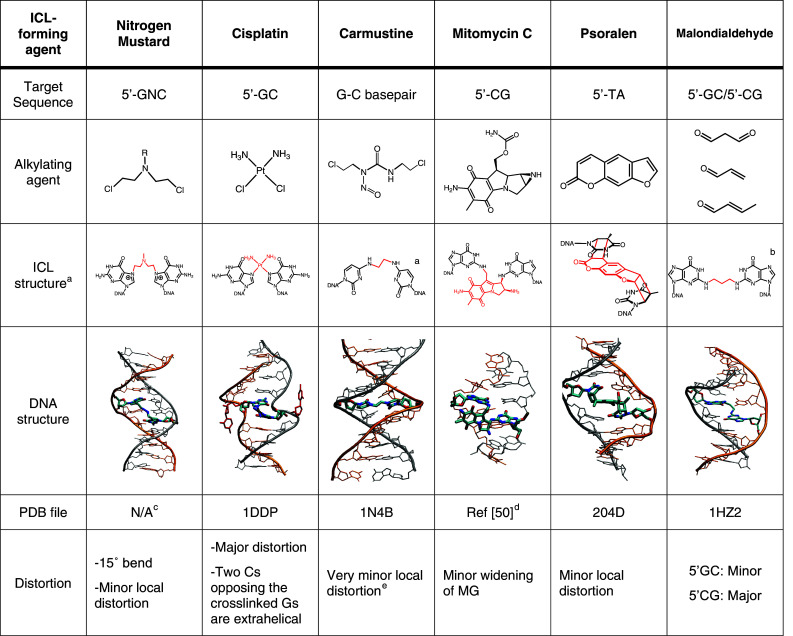

Nitrogen mustard ICLs

Nitrogen mustards react with the N 7 position of guanine residues through the reactive N,N-bis-(2-chloroethyl)amine functional group. NMs preferentially form a 1,3 ICL in a 5′-d(GNC) sequence context [16–18]. It has been shown that NM ICLs induce a slight bend in duplex DNA (~15°) to best accommodate the bridge between the two strands. In fact, the maximal theoretical length of the five-atom bridge formed by NM (~7.5 Å), is less than the average distance between the N 7-G sites in 5′-d(GNC) sequence (~8.9 Å) (Fig. 2) [19, 20]. Initially, NM ICLs were generated by treatment of dsDNA with NMs, yielding only small amounts of ICLs in a non-specific reaction. Additionally, NM ICLs are inherently unstable on a laboratory time scale (in the order of hours to days at room temperature) hindering detailed characterization [21–24]. One way to generate more stable NM ICLs has been to convert them to the stable ring-opened formamidopyrimidine (FAPY) form by treatment with aqueous base enabling initial studies of the repair of NM ICLs in bacteria [16, 25–27], although this approach did not address the problem of selectivity and the final structure of the lesion is significantly different from the original NM ICL.

Fig. 2.

Common ICL-forming agents and their DNA adducts. a Although native BCNU adducts have not yet been synthesized, various mimics have been synthesized and used to study repair. The structure of the ICL and the pdb file refer to one of these mimics. b This ICL has been synthesized in two sequence contexts. This ICL is a reduced and stabilized form of the crosslinks formed by malondialdehyde. c The structure shown here is based on a molecular modeling study [28]. d The coordinates for the mitomycin C ICL were kindly provided by Suse Broyde based on Ref [51]. e The distortion refers to the mimic showed here. The exact distortion provoked by BCNU is not known and is likely to be different than the mimic

We recently developed a strategy to synthesize stable analogs of NM ICLs site-specifically with high specificity and in high yield [20, 28]. This approach involved the incorporation of acetaldehyde functionalities at the 7-positions of G residues in complementary oligonucleotides and use of a double reductive amination reaction to generate the ICL (Fig. 1d). dG was substituted with 7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine to counteract the inherent lability of the glycosidic bond in N 7-alkylated guanines. This approach not only allowed for the synthesis of ICLs isosteric to the drug-induced adducts but also of ICLs that induce a distinct degree of bending of the DNA helix by variation of the length of the bridge linking the two bases on complementary strands. As discussed in more detail below, evidence is increasing that a number of steps in ICL repair, in particular the initial recognition by cellular proteins and interaction with polymerases, are dependent upon the structure of the ICL.

Cisplatin ICLs

Cisplatin was serendipitously discovered as a compound with cytotoxic activity in 1965 [29, 30]. It is still widely used and is particularly successful against testicular cancer. Based on the initial success, many analogous of cisplatin (e.g., carboplatin, oxaliplatin, satraplatin, and picoplatin) have been generated and others are in development to improve the pharmacological properties [31]. Cisplatin is a planar coordination complex of Pt(II) with two chloride ligands in cis-position. Once the molecule enters the cell, the chlorides are displaced by two molecules of water, producing an activated form of cisplatin that is capable of forming adducts with proteins, RNA, and DNA [32]. Like NMs, cisplatin preferentially reacts with the nucleophilic N 7 position of guanine, forming a monoadduct and subsequently forming intra- and interstrand crosslinks. Among these, the 1,2-intrastrand crosslinks (65% at 5′-GG and 25% at 5′-AG) are formed most frequently while 1,3-intrastrand crosslinks (up to 5% at 5′-GNG) and 1,2-interstrand crosslink (up to 8% at 5′-GC) are also formed in significant amounts [32]. The cisplatin interstrand crosslink severely distorts the double helix, due to the shortened distance between two guanines on complementary strands (Fig. 2). The cytosines opposite to the connected guanosines are flipped out into an extrahelical conformation and the DNA is considerably bent [33, 34]. Although no fully synthetic approach to cisplatin ICLs has been reported, these adducts have been prepared relatively efficiently by hybridization directed crosslinking (Fig. 1b). Activated cisplatin (cis-[Pt(NH3)2(H2O)Cl]) is first incubated with an oligonucleotide containing a unique G in a 5′-d(GC) site to generate a monoadduct. Following purification, annealing to a complementary strand results in ICL formation [35]. We have employed this strategy in our laboratory for the preparation of oligonucleotides with a single defined cisplatin ICLs that were inserted into plasmids [36] to study replication-dependent repair of ICLs (see below).

Zhu and Lippard [37] synthesized a derivative of a cisplatin ICL in which one of the amines was conjugated to a photoreactive benzophenone moiety. This photoreactive substrate was used to identify proteins that bind to the ICL in cell extracts revealing important differences in which proteins bind to inter- versus intrastrand crosslinks.

Chloro ethyl nitroso urea ICLs

Chloro ethyl nitroso ureas (CENUs), in particularly carmustine (BCNU), are widely used in cancer chemotherapy and are particularly useful for the treatment of brain tumors due to their ability to pass the blood–brain barrier [38]. The mechanism by which CENUs form ICLs is distinct from that of NMs and cisplatin. CENUs initially alkylate the O 6 position of dG and rapidly react again to form O 6-ethanoguanine, which slowly rearranges to an ICL formed between N 3 of dC and N 1 of dG [39]. Although CENU ICL-containing oligonucleotides have been generated by treatment of oligonucleotides with BCNU [40], strategies for the efficient site-specific generation of this adduct on a larger scale have so far remained elusive. A number of BCNU-like adducts have been synthesized either by incorporation of a precursor (a chloroethyl modified thymine) that can form an ICL with a guanine residue [41] or by incorporation of crosslinked nucleotide dimer into DNA using solid-phase synthesis (Fig. 1c) [42–44]. This later strategy allowed the synthesis of bridges with different lengths and different structures. Although these synthetic adducts are distinct from the CENU ICLs, some of them have started to yield insight into how the repair of ICL that are linked through their Watson–Crick pairing surfaces may differ from those that are linked through either major or minor groves [45, 46].

Mitomycin C: ICLs induced by a natural product

Mitomycin C (MMC) belongs to a class of antibiotics originally isolated from Streptomyces caespitosus and it is widely used in chemotherapy against gastrointestinal tumors, gastric, pancreatic, biliary tract, colorectal, and anal cancer [47]. Mitomycin C only forms adducts with DNA after reduction of its quinone ring reacting mainly with exocyclic amines of dG. After rearrangement and alkylation of a second guanine, it forms ICLs in a 5′-(GC) sequence in addition to intrastrand crosslinks and monoadducts [48, 49]. MMC ICLs are formed in the minor groove, where they induce a moderate widening to accommodate the MMC heterocycle [50, 51]. Since ICLs are formed relatively efficiently by treatment of a duplex with MMC, this agent has been used in cellular ICL repair studies as well as for some biochemical studies [52–54].

Psoralen–ICL formation can be induced by UV light

Psoralens are linear furocumarins isolated from plants and fungi and are used in the treatment of skin disease such as vitiligo or psoriasis. Psoralens intercalate into DNA and can be photoactivated with UV-A radiation to form covalent adducts with thymidine bases, forming interstrand crosslinks (Fig. 2) [55]. This ability to control the activity of psoralen by photoactivation is why this drug is specifically useful for the treatment of skin disease [56] and has made psoralen one of the most useful agents to generate ICL-containing oligonucleotides. Treatment of oligonucleotides containing a specific 5′-AT sequence with psoralen and UV can be controlled to produce mostly ICLs without excessive formation of byproducts such as monoadducts or intrastrand crosslinks. The efficiency of ICL formation has been additionally increased by the use of high-intensity lasers to specifically produce first the monoadduct and then the ICL [57] and by the chemical synthesis and incorporation into DNA by solid-phase synthesis of the monoadduct followed by the UV irradiation to obtain the ICL [58]. Psoralen ICLs have been structurally characterized by NMR [59, 60] and X-ray crystallography [61], revealing that these ICLs locally constrain and distort the DNA at the site of the intercalation but do not change the overall DNA structure (Fig. 2).

Due to the relative ease of preparation and stability, psoralen ICLs have been the most frequently used substrate in investigations of ICL repair in bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells. More recently, Seidman and coworkers [62] developed a method for the induction of spatially defined ICLs in living cells by introduction of psoralen conjugates into cells and generation of ICLs using UV laser irradiation at defined positions in the cell nuclei. In this approach, psoralen was conjugated to a digoxigenin, allowing for the detection of the psoralen ICL by immunofluorescence. This approach allows the study of the recruitment of repair proteins to sites of ICLs [63] and provides a powerful new tool for studying ICL repair.

ICLs formed by endogenous and environmental compounds

Whereas most of the current interest in crosslinking agents stems from their use in cancer chemotherapy, the many endogenous and environmental ICL-forming agents must have been the driving force behind the evolution of the responses they trigger. One large group of agents that can form ICLs includes bifunctional aldehydes that are formed in cellular metabolic processes such as lipid peroxidation [13]. A prototypical bifunctional electrophilic compound is malondialdehyde, which can crosslink DNA via two exocyclic guanine amino groups [64]. A number of additional aldehydes (formaldehyde and acetaldehyde) and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (acrolein, crotonaldehyde), that are found in food, pesticides, and tobacco smoke and can also form DNA ICLs [65, 66]. One characteristic of aldehyde-induced ICLs is that they are intrinsically reversible, which can complicate biochemical and cellular studies. To circumvent this issue, Harris, Rizzo and coworkers [67] devised a way to synthesize a trimethlylene ICL connecting two G residues in the minor groove, representing a reduced and stabilized form of aldehyde ICLs. The structures of these ICLs in 5′-GC and 5′-CG sequence contexts were characterized by NMR [67, 68]. The 5′-GC ICL is readily accommodated in the minor groove and causes little distortion, while the 5′-CG destabilizes the duplex and induces a bend and a twist in the double helix (Fig. 2).

Interstrand crosslinks can be formed from additional potentially endogenous sources. For example, nitric oxide has the ability to form ICLs through diazotization of the exocyclic amine of a G and subsequent ICL formation by reaction with an adjacent G on a complementary strand. This reaction yields an adduct in which two guanine residues are directly linked through a single amine group in the minor groove [69–71]. Such NO-induced ICLs have been incorporated into oligonucleotides as dimers using a solid-phase synthesis strategy [72, 73]. Structural characterization of these ICLs by NMR revealed that although they do not bend the DNA they induce distortion of the double helix by everting the cytosines paired with the crosslinked guanines into an extrahelical position in the minor groove [72].

Finally, the Greenberg laboratory has demonstrated that radicals such as the ones formed at the methyl group of thymidine can from ICLs, pointing to yet another potential endogenous source of ICLs [74, 75].

ICLs pose a difficult problem for the DNA repair machinery

Interstrand crosslinks are uniquely complex lesions, as they need to be removed from both strands of DNA. An intact template for the regeneration of the original DNA sequence is therefore not available as it is for monoadducts that are repaired by base excision or nucleotide excision repair. It became apparent from the first studies of ICL repair in E. coli by Cole [76, 77] that this process requires the interplay of multiple pathways, including nucleotide excision repair (NER) and homologous recombination (HR). The situation is even more complex in eukaryotes, where additional layers of regulation are present and ICLs are repaired by distinct pathways in S and G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle. Thus in addition to NER and HR, repair and signaling pathways like FA, mismatch repair (MMR) and translesion synthesis (TLS) have been implicated in ICL repair.

Replication forks stall at ICLs and trigger their repair

ICLs exhibit the highest levels of toxicity when they block strand separation and polymerase activity of the replication machinery and it is believed that the arrest of the replication fork is the trigger to initiate ICL repair [78]. Any details of replication-dependent repair have remained elusive until very recently, but several classes of proteins have been shown to be involved in ICL repair based on the sensitivity of cell lines with deficiencies in the corresponding genes. Such studies implicated endonucleases, including ERCC1–XPF [79–81] and MUS81–EME1 [82, 83], translesion synthesis polymerases, in particular Polζ and Rev1 [84–86] and proteins involved in homologous recombination, such as Rad54, XRCC2, and XRCC3 [87, 88] in ICL repair. In vertebrates, cells deficient in one of the at least 13 proteins associated with the cancer-prone inherited disorder FA pathway are specifically hypersensitive to ICL-forming agents. The mechanism by which the FA pathway is involved in mediating and regulating ICL repair is slowly emerging [89–91].

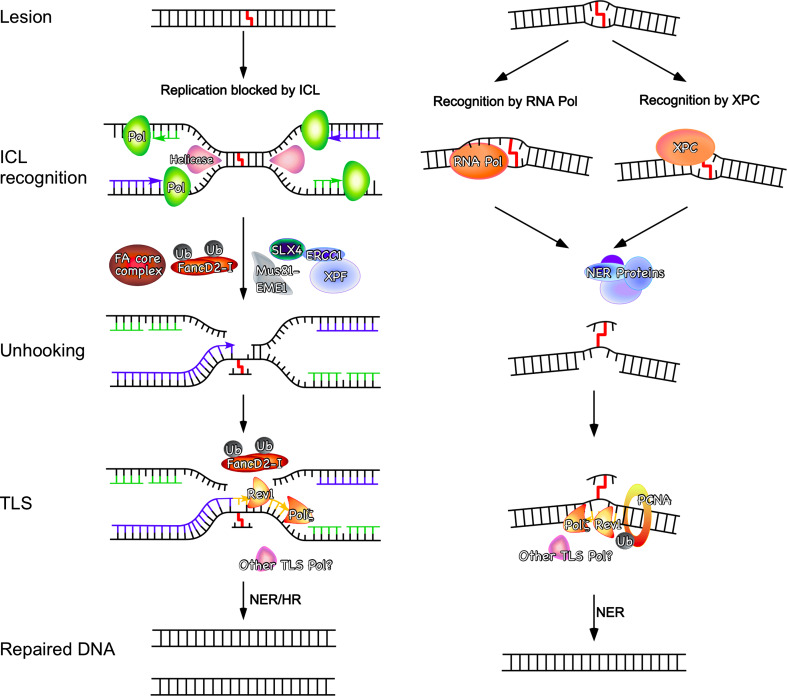

A recent breakthrough in our understanding of ICL repair came from studies in cell-free Xenopus egg extracts, a biochemical system that supports efficient replication of plasmids [92]. To adapt this system to study ICL repair, short oligonucleotides containing site-specific cisplatin or nitrogen mustard-like ICL prepared as described above were ligated into plasmids [36]. Incubation of these ICL-containing plasmids with the extracts allows plasmid replication under physiological conditions. Upon initiation of replication, two forks approach the crosslink from opposite directions, initially stalling at ~20–40 nucleotides from the ICL (Fig. 3). After a delay of ~20 min, one of the leading strands is extended to within one nucleotide of the ICL. At this point, dual incision around the ICL of the lagging strand template leads to unhooking of the ICL, and translesion synthesis leads to bypass of the lesion and full extension of the nascent leading strand. Although it has not yet been experimentally demonstrated, the ICL-remnant may then be removed by NER and the unhooked strand reengaged in replication by homologous recombination in a way similar as for double-strand breaks formed during replication.

Fig. 3.

Models for replication-dependent (left) and -independent (right) ICL repair pathways. In the replication-dependent pathway, the lesion is detected when replication forks are blocked by the ICL. The replication fork initially pauses 20–40 nucleotides from the ICLs, and then approaches to the ICL, activating the FA pathway. The FA core complex ubiquitinates the FANCD2–FANCI complex, a step required for the endonucleases to incise the lagging strand on both sides of the ICL and REV1 and Polζ to extend the leading strand past the ICL. It is believed that HR and possibly NER then complete the process and restore the intact DNA sequence. In G0/G1, the ICL can also be recognized by an RNA polymerase during transcription or, depending on its structure by the NER damage recognition factor XPC-RAD23B. NER proteins are thought to be responsible to unhook the ICL initiating repair synthesis and carrying out TLS past the unhooked ICL in a manner dependent on ubiquitinated PCNA and a TLS polymerase (probably Rev1 and Polζ to bypass the lesion in an potentially error-prone manner. Finally, it is believed that the NER machinery eliminates the ICL remnant restoring the intact DNA

Regulation of ICL repair by the FA pathway

The various steps and factors involved in replication-dependent ICL repair will be discussed here in the framework provided by this study. The stalling of replication forks can trigger many pathways and we will limit discussion here to the FA pathway, which is most relevant to ICL repair. Indeed, the FA pathway is activated in S-phase in particular after exposure to crosslinking agents and this activation is also fully recapitulated in the cell-free Xenopus system. The FA pathway contains three components; the first one is the core complex, which contains eight FANC proteins (A, B, C, E, F, G, L, M) and at least five associated proteins (FAAP100, FAAP24, HES1, MHF1 and MHF2) [91, 93, 94]. Only two proteins of the FA core complex have known catalytic activities: FANCM is a DNA translocase and interacts tightly with MHF1-2 and FAAP24 [93–96]. It has the ability to remodel stalled replication fork structures and it is likely to play a role in loading the FA core complex at replication forks that are stalled at ICLs. FANCM also has a role in activating checkpoint signaling in the absence of the FA core complex [97].

The other protein with known catalytic activity is FANCL, which is a ubiquitin ligase [98, 99] and its activity is required for the monoubiquitination of the FANCD2–FANCI proteins, the second component of the FA pathway [100, 101]. Ubiquitination of FANCD2–FANCI leads to colocalization of the heterodimer with other DNA repair factors in chromatin and is essential for mediating cellular resistance to crosslinking agents. A matter of debate for a long time, the direct role of FANCD2–FANCI in ICL repair was recently demonstrated in a cell-free Xenopus system using a site-specific cisplatin ICL [102]. In the absence of FANCD2–FANCI or in the presence of a mutant FANCD2 protein that can no longer be ubiquitinated (K562R), the replication fork was still able to approach the ICL to the −1 position, but both the unhooking and translesion synthesis steps were blocked. This result thus suggests that ubiquitinated FANCD2–FANCI complex has a direct role in recruiting nucleases and/or translesion synthesis polymerases to the sites of ICLs (see below).

The remaining FA proteins, FANCD1 (better known as BRCA2), FANCJ (a helicase, also known as BACH1 or BRIP1) and FANCN (also know as PALB2) act downstream of FANCD2–FANCI are believed to have a role in mediating recombination later in the pathway [91].

Recently, it has been suggested that the FA pathway may also function outside of replication, but the mechanisms by which this might occur are not yet clear [103, 104].

Which endonucleases are involved in unhooking the ICL?

An important feature of ICL repair in eukaryotes is that double-stranded breaks (DSBs) are induced at stalled replication forks [78, 80, 105]. They are likely probably induced in an unhooking step immediately before the replication machinery bypasses the lesion (Fig. 3). Two structure-specific endonucleases involved in ICL repair are ERCC1–XPF and MUS81–EME1, since cells defective in these enzymes are hypersensitive to crosslinking agents [79, 81, 82, 106]. Both of these enzymes cleave ss/dsDNA junction with 5′ ssDNA overhangs and therefore have the wrong polarity to make the first cut to generate DSBs in ICL repair [107]. In line with this view, studies have shown that neither ERCC1–XPF nor MUS81–EME1 are absolutely required for the formation of DSBs in response to crosslinking agents during S-phase as evidenced by the formation of γ-H2AX-foci, cellular markers of DSBs [81, 106]. Although dissenting views have been voiced as well [82, 108], it is most likely that the these two nucleases are instead involved in mediating the second incision in ICL repair [80, 109, 110] or perhaps also in resolving intermediates further downstream in the pathway during the homologous recombination step [111]. Both proteins seem to be recruited to the site of ICL repair by interaction with the SLX4 protein, which can also form a Holliday junction resolvase with another nuclease SLX1. Knock-down of SLX4 renders cells sensitive to crosslinking agents and SLX4 may therefore have a special role in coordinating nuclease activities at ICL [112–115]. Since SLX4 also contains a ubiquitin-binding (UBZ) domain, this may happen by interaction with a ubiquitinated protein such as FANCD2–FANCI.

Despite the implication of a number of nucleases in unhooking ICLs, it is likely that the protein(s) that makes the first incision on the lagging strand has not yet been identified.

Translesion synthesis restores the leading strand during ICL repair

Translesion synthesis is an essential step in replication-dependent (and replication-independent, see below) repair as it restores one of the two strands affected by the ICL (Fig. 3). Human cells contain at least 15 polymerases, many of which have the ability to bypass various types of DNA damage [116, 117]. Among these, there is a striking sensitivity of cells deficient in Polζ (Rev3–Rev7) and Rev1 to crosslinking agents [86]. Chicken DT40 cells deficient in Rev3 are in fact more sensitive than any other cell line to crosslinking agents pointing to a key role of this polymerase in ICL repair. The polymerase activity of Rev1 is limited to the insertion of a single dCTP opposite a damaged base while Polζ is generally considered to be a good extender polymerase and the two polymerases often act in concert [118]. The kinetics of ICL repair in the Xenopus egg extracts system suggest that one polymerase may insert a dNTP opposite the crosslinked nucleotide, while a second polymerase may responsible for the extension past the ICL [36]. Depletion of Rev7 from the Xenopus extracts leads to an additional stalling of the replication fork at the 0 position at a cisplatin ICLs, after insertion of a dNTP opposite the ICL, strongly suggesting that Polζ is responsible for the extension step past the ICL.

While these observations cumulatively suggest that Rev1 and Polζ are the key players for the TLS step in ICL repair, there is increasing evidence that additional polymerases take part in this process. For example, while the bypass of the helix-distorting cisplatin ICLs was dependent on Rev7 in Xenopus egg extracts, a nitrogen-mustard-like ICL that does not distort the DNA helix was bypassed with comparable efficiency in the presence and absence of Rev7. This indicates that other polymerases are able to bypass this ICL. Indeed, other TLS polymerases such as Polη, Polκ, or Polι are able to bypass such non-distorting ICLs in vitro under certain conditions (Ho T.V., A.G., O.D.S., unpublished observations). Lloyd and coworkers have studied the ability of minor groove trimethylene ICLs (Fig. 2) or non-distorting major groove ICLs. They found that these minor groove ICLs were readily and specifically bypassed by Polκ [66], whereas the major groove ICL were specifically bypassed by Polν [119]. The studies suggest that the bypass of ICLs by polymerases is highly dependent of the structure of the ICL and that a number of polymerases aside from Rev1 and Polζ may contribute to the process.

The completion of replication-dependent ICL repair involves homologous recombination and possibly nucleotide excision repair. The unhooked crosslink now resembles a “common” NER substrate, affecting only one strand, however genetic experiments showed only mild sensitivity to cells defective in NER genes other than ERCC1–XPF. On the other hand, loss of HR proteins showed substantially increased sensitivity to crosslinking agents. The role of HR in ICL repair has been recently reviewed by Hinz [120].

Replication-independent ICL repair

While most evidence points to replication-dependent repair being the main mechanism of dealing with ICLs, there is now robust support for ICL repair mechanisms in G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle (reviewed in [121]). The contribution of replication-independent pathways to ICL repair has not been fully appreciated, primarily because the extreme toxicity of ICLs is most apparent when a replication fork is blocked. Therefore, cells with deficiencies in genes that contribute to ICL repair during the S phase display higher toxicity when exposed to crosslinking agents.

Conclusive evidence for a replication-independent pathway stems from several experimental systems. Genetic studies in the yeast S. cerevisiae have revealed that NER and TLS pathways are essential for the repair of nitrogen mustard ICLs in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle [122]. The use of reporter assays has suggested similar pathways in mammalian cells [54, 123, 124]. In these studies, oligonucleotides containing site-specific ICLs were ligated into the promoter region of a gene of a plasmid. Activation of gene expression required the repair of the ICLs in mammalian cells. These studies showed that, consistently with the studies in S. cerevisiae, ICLs were repaired by a pathway involving NER and TLS. A number of ICLs were repaired in this way, including those formed by psoralen [123], mitomycin C [54] N 4C-N 4C and N 3T-N 3T alkyl ICLs [125], and cisplatin (Enoiu M., O.D.S., unpublished observations). As it has been shown for replication-dependent ICL repair, the TLS polymerases Rev1 and Polζ are of particular importance for the bypass of ICLs [124], in line with the observation that deletions in Rev1 and Polζ render DT40 cells more sensitive to crosslinking agents than deletions in any other gene [126]. The TLS polymerases are recruited to bypass the ICLs in G0/G1 in dependence of ubiquitination of PCNA by Rad18 [122, 124], similar to TLS of single-stranded lesions.

Interestingly, the recognition of some ICLs (psoralen, MMC) occurs by global genome NER (GG-NER) involving XPC-RAD23B [54, 123], while the repair of others (alkyl ICLs, cisplatin) was found to be dependent on transcription-coupled NER (TC-NER) [125] (Enoiu M., O.D.S., unpublished observations). The efficiency of NER of lesions affecting one strand of DNA is believed to be roughly proportional to the amount of thermodynamic destabilization induced by a lesion [127]. By contrast, it is believed that all bulky adducts can stall an RNA polymerase and trigger TC-NER (in the transcribed strands of active genes) [128]. An example of a lesion that is addressed mainly by TC-NER is the cyclopyrimidine dimer (CPD), which induces only minor distortion in the DNA [54, 127].

Although NER clearly plays a role in repairing ICLs, our understanding of how these lesions interact with NER proteins is limited. Although it has been shown that XPC-RAD23B is likely to be the first NER protein to arrive at psoralen ICLs in living cells [129], very little is known about how various ICLs are recognized by NER proteins. It is intriguing that cisplatin ICLs, which are highly helix-distorting [33], are not repaired by GG-NER [130], whereas psoralen or MMC ICLs, which are less distorting, are processed by GG-NER [54, 123, 129]. It therefore appears that the rules of damage recognition in NER and binding by XPC-RAD23B as they have been defined for lesions on one strand of DNA simply do not apply for ICLs [131–133]. It has been suggested that the mismatch repair proteins MutSβ (MSH2–MSH3) may play a role in facilitating the recognition of ICLs by NER and perhaps also independently of NER [134, 135]. The structural features that trigger NER of ICLs therefore remain to be determined.

In vitro studies of processing of ICLs by NER have revealed additional features that differ from canonical repair. NER proteins have been shown to make two incisions on one side of a psoralen or N 4C-ethyl-N 4C ICL, resulting in a gap 5′ to an ICL [45, 136, 137]. Such a gap could in principle facilitate TLS past the ICL, perhaps in conjunction with an incision 3′ to the lesion mediated by a nuclease that is not involved in NER, but the physiological relevance of this observation remains to be established.

Toward the discovery of clinically useful inhibitors of ICL repair

As it has been shown that the repair of ICLs in tumor cells leads to resistance to treatment with crosslinking agents such as cisplatin or NMs [138, 139], the inhibition of these repair pathways is an important goal for anti-tumor therapy. The recent demonstration that the inhibition of ssDNA break repair protein PARP in BRCA2-deficient tumors is synthetically lethal, demonstrates that DNA repair inhibitors can be effective even in the absence of DNA-damaging agents [140–142].

As discussed above, the repair of ICLs is a complex affair and involves players from many different DNA repair pathways. To ensure specific and efficient inhibitory effects in conjunction with the treatment of crosslinking agents, it would be desirable to target those pathways that are specifically responsible for the repair of ICLs. With the advances of our understanding of ICL repair, proteins and pathways that may be targeted to inhibit ICL repair are emerging.

So far, the FA pathway has received most of the attention as a target due to the specific sensitivity of FA-deficient cells to crosslinking agents. Indeed, preclinical model studies in mice have revealed that disruption of FA core complex proteins FANCC and FANCG in adenocarcinoma cell lines abrogates FANCD2 monoubiquitylation and renders cells sensitive to agents such oxaliplatin and melphalan [143, 144]. To date, screens for inhibitors of the FA pathway have mostly focused on the most clearly discernable step, the ubiquitination of FANCD2–FANCI and the concomitant translocation of these two proteins into cellular foci and chromatin. D’Andrea and coworkers [145] used a cellular screen to identify compounds that inhibit the translocation of a GFP-labeled FANCD2 to nuclear foci following genotoxic treatment. The Hoatlin laboratory used Xenopus laevis cell-free extracts to screen for small molecules that inhibit FANCD2 ubiquitination upon incubation with different DNA molecules [146]. These two studies identified inhibitors of the FA pathway, including the natural product curcumin and derivatives thereof, that render cells sensitive to treatment with crosslinking agents. Gallmeier et al. [144] carried out a different type of screen to identify compounds that are selectively toxic to FA-deficient cells, yielding a number of interesting lead compounds. These studies raise the possibility that FA inhibitors with clinically useful properties may be found, both as a chemosensitizers in cisplatin-based cancer treatment and as synthetic-lethal agents in tumors with defects in the FA genes. Further development of FA pathway inhibitors will require a more detailed understanding of the mechanisms by which the identified compounds operate. Furthermore, emerging structural studies of FA proteins [99, 147] and a better understanding of the mechanisms by which FA proteins such as FANCM contribute to ICL repair will provide additional opportunities for inhibitors that target FA proteins.

As discussed above, another group of proteins that have ICL repair-specific functions are the endonucleases that make incisions around ICLs during replication-dependent repair. Although proteins like ERCC1–XPF have a number of functions, recent studies suggest that this protein is recruited to sites of ICL repair through specific interaction with partners such as SLX4 [112–115]. Importantly, cells expressing mutant ERCC1–XPF with a specific defect in NER are not sensitive to crosslinking agents such as cisplatin or MMC [148], suggesting that the identification and characterization of interaction sites that recruit nucleases to carry out their function in ICL repair may be fruitful targets for therapeutic intervention.

Concluding remarks

The repair of ICLs is accomplished by an assembly of many components from different repair pathways. Our understanding of the intricate network of interaction between signaling and repair pathways triggered by ICLs is still far from complete. The development of new methods to synthesize oligonucleotides containing site-specific ICLs has been an important advance for the field. These oligonucleotides have been incorporated into plasmids and used in cell-free extracts and living cells to study ICL repair pathways. Together with cell-biology and genetic approaches, this will aid the understanding of the molecular basis of how ICL repair differs from repair pathways of lesions that only affect one strand of DNA. These insights should provide opportunities to find new targets for drug developments to increase the therapeutic efficiency of crosslinking agents and to target tumor cells with specific defects in ICL repair.

Acknowledgments

We thank Suse Broyde (NYU) for providing the coordinates for the mitomycin C ICL. Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by NIH grants GM080454, CA092584, and ES004068.

Abbreviations

- ICL

Interstrand crosslink

- NM

Nitrogen mustards

- NER

Nucleotide excision repair

- CENU

Chloro nitroso urea

- MMC

Mitomycin C

- FA

Fanconi anemia

- HR

Homologous recombination

- TLS

Translesion synthesis

Note added in proof

A candidate nuclease to make the first incision in the lagging strand in replication-dependent ICL repair has recently been discovered. This protein, FAN1 (Fanconi-associated nuclease 1) interacts with ubiquitination FancD2-FancI, has the appropriate polarity of incision, and knock-down of FAN1 renders cells sensitive to crosslinking agents. See McKay C, Declais AC, Lundin C, Agostino A, Deans AJ, MacArtney TJ, Hofamn K, Gartner A, West SC, Helleday T, Lilley DM, Rouse J (2010) Identification of KIAA1018/FAN1, a DNA repair nuclease recruited to DNA damage by monoubiquitinated FANCD2. Cell 142:65–76; Kratz K, Schöpf B, Kaden S, Sendoel A, Eberhard R, Lademann C, Cannavó E, Sartori AA, Hengartner MO, Jiricny J (2010) Deficiency of FANCD2-associated nuclease KIAA1018/FAN1 sensitizes cells to interstrand crosslinking agents. Cell 142:77–88; Smogorzewska A, Desetty R, Saito TT, Schlabach M, Lach FP, Sowa ME, Clark AB, Kunkel TA, Harper JW, Colaiácovo MP, Elledge SJ (2010) A genetic screen identifies FAN1, a Facnoni anemia-associated nuclease necessary for DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mol Cell 39:36–47. Liu T, Ghosal G, Yuan J, Chen J, Huang J (2010) FAN1 acts with FANCI-FANCD2 to promote DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Science 329:693–696.

References

- 1.DeVita VT, Chu E. A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8643–8653. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein RJ. Drug-induced DNA damage and tumor chemosensitivity. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:2062–2084. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.12.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schärer OD. DNA interstrand crosslinks: natural and drug-induced DNA adducts that induce unique cellular responses. Chembiochem. 2005;6:27–32. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noll DM, Mason TM, Miller PS. Formation and repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA. Chem Rev. 2006;106:277–301. doi: 10.1021/cr040478b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman L, Wintrobe M, Dameshek W, Goodman M, Gilman A. Nitrogen mustard therapy—use of methyl-bis(beta-chloroethyl)amine hydrochloride and tris(beta-chloroethyl)amine hydrochloride for Hodgkin's disease, lymphosarcoma, leukemia and certain allied and miscellaneous disorders. J Am Med Assoc. 1946;132:126–132. doi: 10.1001/jama.1946.02870380008004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohn KW. Beyond DNA cross-linking: history and prospects of DNA-targeted cancer treatment—Fifteenth Bruce F. Cain Memorial Award lecture. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5533–5546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilman A, Philips F. The biological actions and therapeutic applications of the B-chloroethyl amines and sulfides. Science. 1946;103:409–436. doi: 10.1126/science.103.2675.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geiduschek EP. “Reversible” DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1961;47:950–955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.7.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brookes P, Lawley PD. The reaction of mono- and di-functional alkylating agents with nucleic acids. Biochem J. 1961;80:496–503. doi: 10.1042/bj0800496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohn KW, Spears CL, Doty P. Inter-strand crosslinking of DNA by nitrogen mustard. J Mol Biol. 1966;19:266–288. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajski SR, Williams RM. DNA cross-linking agents as antitumor drugs. Chem Rev. 1998;98:2723–2796. doi: 10.1021/cr9800199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone MP, Cho Y-J, Huang H, Kim H-Y, Kozekov ID, Kozekova A, Wang H, Minko IG, Lloyd RS, Harris TM, Rizzo CJ. Interstrand DNA cross-links induced by alpha, beta-unsaturated aldehydes derived from lipid peroxidation and environmental sources. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41:793–804. doi: 10.1021/ar700246x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panasci L, Xu Z-Y, Bello V, Aloyz R. The role of DNA repair in nitrogen mustard drug resistance. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:211–220. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHugh PJ, Spanswick VJ, Hartley JA. Repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks: molecular mechanisms and clinical relevance. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:483–490. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojwang JO, Grueneberg DA, Loechler EL. Synthesis of a duplex oligonucleotide containing a nitrogen mustard interstrand DNA–DNA cross-link. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6529–6537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rink S, Solomon M, Taylor M, Rajur S, McLaughlin L, Hopkins P. Covalent Structure of a nitrogen mustard-induced DNA interstrand cross-link—an N7-to-N7 linkage of deoxyguanosine residues at the duplex sequence 5′-d(GNC) J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2551–2557. doi: 10.1021/ja00060a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millard J, Raucher S, Hopkins P. Mechlorethamine cross-links deoxyguanosine residues at 5′-GNC sequences in duplex DNA fragments. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2459–2460. doi: 10.1021/ja00162a079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rink SM, Hopkins PB. A mechlorethamine-induced DNA interstrand cross-link bends duplex DNA. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1439–1445. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guainazzi A, Campbell AJ, Angelov T, Simmerling C, Schärer OD (2010) Synthesis and molecular modeling of a nitrogen mustard DNA interstrand crosslink. Chem Eur J (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kallama S, Hemminki K. Alkylation of guanosine by phosphoramide mustard, chloromethine hydrochloride and chlorambucil. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1984;54:214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1984.tb01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kallama S, Hemminki K. Stabilities of 7-alkylguanosines and 7-deoxyguanosines formed by phosphoramide mustard and nitrogen mustard. Chem Biol Interact. 1986;57:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(86)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan Y, Gold B. Sequence-specificity for DNA interstrand cross-linking by alpha, ω-alkanediol dimethylsulfonate esters: evidence for DNA distortion by the initial monofunctional lesion. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11942–11946. doi: 10.1021/ja991813u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta JR, Przybylski M, Ludlum DB. Alkylation of guanosine and deoxyguanosine by phosphoramide mustard. Cancer Res. 1980;40:4183–4186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grueneberg D, Ojwang J, Benasutti M, Hartman S, Loechler E. Construction of a human shuttle vector containing a single nitrogen mustard interstrand, DNA–DNA cross-link at a unique plasmid location. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2268–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berardini M, Mackay W, Loechler E. Evidence for a recombination-independent pathway for the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links based on a site-specific study with nitrogen mustard. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3506–3513. doi: 10.1021/bi962778w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berardini M, Foster P, Loechler E. DNA polymerase II (polB) is involved in a new DNA repair pathway for DNA interstrand cross-links in Escherichia coli . J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2878–2882. doi: 10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t031385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelov T, Guainazzi A, Schärer OD. Generation of DNA interstrand cross-links by post-synthetic reductive amination. Org Lett. 2009;11:661–664. doi: 10.1021/ol802719a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg B, VanCamp L, Trosko JE, Mansour VH. Platinum compounds: a new class of potent antitumour agents. Nature. 1969;222:385–386. doi: 10.1038/222385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg B, VanCamp L, Krigas T. Inhibition of cell division in Escherichia coli by electrolysis products from a platinum electrode. Nature. 1965;205:698–699. doi: 10.1038/205698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Structure, recognition, and processing of cisplatin-DNA adducts. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, Zhu L, Reid BR, Drobny GP, Hopkins PB. Solution structure of a cisplatin-induced DNA interstrand cross-link. Science. 1995;270:1842–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coste F, Malinge JM, Serre L, Shepard W, Roth M, Leng M, Zelwer C. Crystal structure of a double-stranded DNA containing a cisplatin interstrand cross-link at 1.63 Å resolution: hydration at the platinated site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1837–1846. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.8.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofr C, Brabec V. Thermal and thermodynamic properties of duplex DNA containing site-specific interstrand cross-link of antitumor cisplatin or its clinically ineffective trans isomer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9655–9661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Räschle M, Knipscheer P, Knipsheer P, Enoiu M, Angelov T, Sun J, Griffith JD, Ellenberger TE, Schärer OD, Walter JC. Mechanism of replication-coupled DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Cell. 2008;134:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu G, Lippard SJ. Photoaffinity labeling reveals nuclear proteins that uniquely recognize cisplatin-DNA interstrand cross-links. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4916–4925. doi: 10.1021/bi900389b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johannessen T-CA, Bjerkvig R, Tysnes BB. DNA repair and cancer stem-like cells—potential partners in glioma drug resistance? Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludlum DB. The chloroethylnitrosoureas: sensitivity and resistance to cancer chemotherapy at the molecular level. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:588–598. doi: 10.3109/07357909709047601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischhaber PL, Gall AS, Duncan JA, Hopkins PB. Direct demonstration in synthetic oligonucleotides that N, N′-bis(2-chloroethyl)-nitrosourea cross links N1 of deoxyguanosine to N3 of deoxycytidine on opposite strands of duplex DNA. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4363–4368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alzeer J, Schärer OD. A modified thymine for the synthesis of site-specific thymine–guanine DNA interstrand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4458–4466. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noll DM, Noronha AM, Miller PS. Synthesis and characterization of DNA duplexes containing an N(4)C-ethyl-N(4)C interstrand cross-link. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3405–3411. doi: 10.1021/ja003340t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilds CJ, Noronha AM, Robidoux S, Miller PS. Mispair-aligned N3T-alkyl-N3T interstrand cross-linked DNA: synthesis and characterization of duplexes with interstrand cross-links of variable lengths. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9257–9265. doi: 10.1021/ja0498540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilds CJ, Xu F, Noronha AM. Synthesis and characterization of DNA containing an N-1-2′-deoxyinosine-ethyl-N-3-thymidine interstrand cross-link: a structural mimic of the cross-link formed by 1, 3-bis-(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:686–695. doi: 10.1021/tx700422h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smeaton MB, Hlavin EM, McGregor Mason T, Noronha AM, Wilds CJ, Miller PS. Distortion-dependent unhooking of interstrand cross-links in mammalian cell extracts. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9920–9930. doi: 10.1021/bi800925e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smeaton MB, Hlavin EM, Noronha AM, Murphy SP, Wilds CJ, Miller PS. Effect of cross-link structure on DNA interstrand cross-link repair synthesis. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1285–1297. doi: 10.1021/tx9000896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hofheinz R-D, Beyer U, Al-Batran S-E, Hartmann JT. Mitomycin C in the treatment of gastrointestinal tumours: recent data and perspectives. Onkologie. 2008;31:271–281. doi: 10.1159/000122590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomasz M, Lipman R, Chowdary D, Pawlak J, Verdine GL, Nakanishi K. Isolation and structure of a covalent cross-link adduct between mitomycin C and DNA. Science. 1987;235:1204–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.3103215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomasz M, Chowdary D, Lipman R, Shimotakahara S, Veiro D, Walker V, Verdine GL. Reaction of DNA with chemically or enzymatically activated mitomycin C: isolation and structure of the major covalent adduct. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6702–6706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rink SM, Lipman R, Alley SC, Hopkins PB, Tomasz M. Bending of DNA by the mitomycin C-induced, GpG intrastrand cross-link. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:382–389. doi: 10.1021/tx950156q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Norman D, Live D, Sastry M, Lipman R, Hingerty BE, Tomasz M, Broyde S, Patel DJ. NMR and computational characterization of mitomycin cross-linked to adjacent deoxyguanosines in the minor groove of the d(T-A-C-G-T-A).d(T-A-C-G-T-A) duplex. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2861–2875. doi: 10.1021/bi00463a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warren AJ, Ihnat MA, Ogdon SE, Rowell EE, Hamilton JW. Binding of nuclear proteins associated with mammalian DNA repair to the mitomycin C-DNA interstrand crosslink. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1998;31:70–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1998)31:1<70::AID-EM10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mustra DJ, Warren AJ, Hamilton JW. Preferential binding of human full-length XPA and the minimal DNA binding domain (XPA-MF122) with the mitomycin C-DNA interstrand cross-link. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7158–7164. doi: 10.1021/bi002820u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng H, Wang X, Warren A, Legerski R, Nairn R, Hamilton J, Li L. Nucleotide excision repair- and polymerase eta-mediated error-prone removal of mitomycin C interstrand cross-links. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:754–761. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.754-761.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cimino G, Gamper H, Isaacs S, Hearst J. Psoralens as photoactive probes of nucleic acid structure and function: organic chemistry, photochemistry, and biochemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:1151–1193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stern RS. Psoralen and ultraviolet a light therapy for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:682–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct072317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spielmann HP, Sastry SS, Hearst JE. Methods for the large-scale synthesis of psoralen furan-side monoadducts and diadducts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4514–4518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobertz W, Essigmann JM. Solid-phase synthesis of oligonucleotides containing a site-specific psoralen derivative. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5960–5961. doi: 10.1021/ja9703178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spielmann HP, Dwyer TJ, Hearst JE, Wemmer DE. Solution structures of psoralen monoadducted and cross-linked DNA oligomers by NMR spectroscopy and restrained molecular dynamics. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12937–12953. doi: 10.1021/bi00040a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang GS, Kim JK, Choi BS. The solution structure of a psoralen cross-linked DNA duplex by NMR and relaxation matrix refinement. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:191–197. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinden RR, Hagerman PJ. Interstrand psoralen cross-links do not introduce appreciable bends in DNA. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6299–6303. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thazhathveetil AK, Liu ST, Indig FE, Seidman MM. Psoralen conjugates for visualization of genomic interstrand cross-links localized by laser photoactivation. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:431–437. doi: 10.1021/bc060309t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Majumdar A, Muniandy PA, Liu J, Liu JL, Liu ST, Cuenoud B, Seidman MM. Targeted gene knock in and sequence modulation mediated by a psoralen-linked triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11244–11252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niedernhofer LJ, Daniels JS, Rouzer CA, Greene RE, Marnett LJ. Malondialdehyde, a product of lipid peroxidation, is mutagenic in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31426–31433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng G, Shi Y, Sturla SJ, Jalas JR, McIntee EJ, Villalta PW, Wang M, Hecht SS. Reactions of formaldehyde plus acetaldehyde with deoxyguanosine and DNA: formation of cyclic deoxyguanosine adducts and formaldehyde cross-links. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:145–152. doi: 10.1021/tx025614r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minko IG, Harbut MB, Kozekov ID, Kozekova A, Jakobs PM, Olson SB, Moses RE, Harris TM, Rizzo CJ, Lloyd RS. Role for DNA polymerase kappa in the processing of N2-N2-guanine interstrand cross-links. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17075–17082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801238200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dooley PA, Tsarouhtsis D, Korbel GA, Nechev LV, Shearer J, Zegar IS, Harris CM, Stone MP, Harris TM. Structural studies of an oligodeoxynucleotide containing a trimethylene interstrand cross-link in a 5′-(CpG) motif: model of a malondialdehyde cross-link. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1730–1739. doi: 10.1021/ja003163w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dooley PA, Zhang M, Korbel GA, Nechev LV, Harris CM, Stone MP, Harris TM. NMR determination of the conformation of a trimethylene interstrand cross-link in an oligodeoxynucleotide duplex containing a 5′-d(GpC) motif. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:62–72. doi: 10.1021/ja0207798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shapiro R, Dubelman S, Feinberg AM, Crain PF, McCloskey JA. Isolation and identification of cross-linked nucleosides from nitrous acid treated deoxyribonucleic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:302–303. doi: 10.1021/ja00443a080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kirchner J, Hopkins P. Nitrous-acid cross-links duplex DNA fragments through deoxyguanosine residues at the sequence 5′-CG. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4681–4682. doi: 10.1021/ja00012a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Caulfield JL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Nitric oxide-induced interstrand cross-links in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:571–574. doi: 10.1021/tx020117w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Edfeldt NBF, Harwood EA, Sigurdsson ST, Hopkins PB, Reid BR. Solution structure of a nitrous acid induced DNA interstrand cross-link. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2785–2794. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harwood E, Sigurdsson S, Edfeldt N, Reid B, Hopkins PB. Chemical synthesis and preliminary structural characterization of a nitrous acid interstrand cross-linked duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5081–5082. doi: 10.1021/ja984426d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hong IS, Greenberg MM. Efficient DNA interstrand cross-link formation from a nucleotide radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3692–3693. doi: 10.1021/ja042434q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hong IS, Ding H, Greenberg MM. Oxygen independent DNA interstrand cross-link formation by a nucleotide radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:485–491. doi: 10.1021/ja0563657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cole R. Repair of DNA containing interstrand crosslinks in Escherichia coli: sequential excision and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:1064–1068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cole R, Levitan D, Sinden R. Removal of psoralen interstrand cross-links from DNA of Escherichia coli: mechanism and genetic control. J Mol Biol. 1976;103:39–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Akkari Y, Bateman R, Reifsteck C, Olson S, Grompe M. DNA replication is required to elicit cellular responses to psoralen-induced DNA interstrand cross-links. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8283–8289. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.21.8283-8289.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoy CA, Thompson LH, Mooney CL, Salazar EP. Defective DNA cross-link removal in Chinese hamster cell mutants hypersensitive to bifunctional alkylating agents. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1737–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.De Silva IU, McHugh PJ, Clingen PH, Hartley JA. Defining the roles of nucleotide excision repair and recombination in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7980–7990. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.21.7980-7990.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Niedernhofer LJ, Odijk H, Budzowska M, van Drunen E, Maas A, Theil AF, de Wit J, Jaspers NGJ, Beverloo HB, Hoeijmakers JHJ, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1–Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–5787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hanada K, Budzowska M, Modesti M, Maas A, Wyman C, Essers J, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81–Eme1 promotes conversion of interstrand DNA crosslinks into double-strands breaks. EMBO J. 2006;25:4921–4932. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hanada K, Budzowska M, Davies S, van Drunen E, Onizawa H, Beverloo HB, Maas A, Essers J, Hickson I, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81 contributes to replication restart by generating double-strand DNA breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Simpson LJ, Sale JE. Rev1 is essential for DNA damage tolerance and non-templated immunoglobulin gene mutation in a vertebrate cell line. EMBO J. 2003;22:1654–1664. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Niedzwiedz W, Mosedale G, Johnson M, Ong C, Pace P, Patel KJ. The Fanconi anaemia gene FANCC promotes homologous recombination and error-prone DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2004;15:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gan GN, Wittschieben JP, Wittschieben BØ, Wood RD. DNA polymerase zeta (pol zeta) in higher eukaryotes. Cell Res. 2008;18:174–183. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Essers J, Hendriks RW, Swagemakers SM, Troelstra C, de Wit J, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. Disruption of mouse RAD54 reduces ionizing radiation resistance and homologous recombination. Cell. 1997;89:195–204. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu N, Lamerdin JE, Tebbs RS, Schild D, Tucker JD, Shen MR, Brookman KW, Siciliano MJ, Walter CA, Fan W, Narayana LS, Zhou ZQ, Adamson AW, Sorensen KJ, Chen DJ, Jones NJ, Thompson LH. XRCC2 and XRCC3, new human Rad51-family members, promote chromosome stability and protect against DNA cross-links and other damages. Mol Cell. 1998;1:783–793. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Niedernhofer LJ, Lalai AS, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Fanconi anemia (cross)linked to DNA repair. Cell. 2005;123:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrg2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moldovan G-L, D’Andrea AD. How the Fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:223–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Walter J, Sun L, Newport J. Regulated chromosomal DNA replication in the absence of a nucleus. Mol Cell. 1998;1:519–529. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yan Z, Delannoy M, Ling C, Daee D, Osman F, Muniandy PA, Shen X, Oostra AB, Du H, Steltenpool J, Lin T, Schuster B, Décaillet C, Stasiak A, Stasiak AZ, Stone S, Hoatlin ME, Schindler D, Woodcock CL, Joenje H, Sen R, de Winter JP, Li L, Seidman MM, Whitby MC, Myung K, Constantinou A, Wang W. A histone-fold complex and FANCM form a conserved DNA-remodeling complex to maintain genome stability. Mol Cell. 2010;37:865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singh TR, Saro D, Ali AM, Zheng X-F, Du C-h, Killen MW, Sachpatzidis A, Wahengbam K, Pierce AJ, Xiong Y, Sung P, Meetei AR. MHF1-MHF2, a histone-fold-containing protein complex, participates in the Fanconi anemia pathway via FANCM. Mol Cell. 2010;37:879–886. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meetei AR, Medhurst AL, Ling C, Xue Y, Singh TR, Bier P, Steltenpool J, Stone S, Dokal I, Mathew CG, Hoatlin M, Joenje H, de Winter JP, Wang W. A human ortholog of archaeal DNA repair protein Hef is defective in Fanconi anemia complementation group M. Nat Genet. 2005;37:958–963. doi: 10.1038/ng1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ciccia A, Ling C, Coulthard R, Yan Z, Xue Y, Meetei AR, Laghmani EH, Joenje H, McDonald N, de Winter JP, Wang W, West SC. Identification of FAAP24, a Fanconi anemia core complex protein that interacts with FANCM. Mol Cell. 2007;25:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Collis SJ, Ciccia A, Deans AJ, Horejsí Z, Martin JS, Maslen SL, Skehel JM, Elledge SJ, West SC, Boulton SJ. FANCM and FAAP24 function in ATR-mediated checkpoint signaling independently of the Fanconi anemia core complex. Mol Cell. 2008;32:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Meetei A, de Winter JP, Medhurst A, Wallisch M, Waisfisz Q, van de Vrugt H, Oostra A, Yan Z, Ling C, Bishop C, Hoatlin M, Joenje H, Wang W. A novel ubiquitin ligase is deficient in Fanconi anemia. Nat Genet. 2003;35:165–170. doi: 10.1038/ng1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cole AR, Lewis LPC, Walden H. The structure of the catalytic subunit FANCL of the Fanconi anemia core complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:294–298. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, Meyn M, Timmers C, Hejna J, Grompe M, D’Andrea AD. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–262. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Smogorzewska A, Matsuoka S, Vinciguerra P, McDonald E, Hurov K, Luo J, Ballif B, Gygi S, Hofmann K, D’Andrea AD, Elledge S. Identification of the FANCI protein, a monoubiquitinated FANCD2 paralog required for DNA repair. Cell. 2007;129:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Knipscheer P, Räschle M, Smogorzewska A, Enoiu M, Ho TV, Schärer OD, Walter JC, Elledge SJ. The Fanconi anemia pathway promotes replication-dependent DNA interstrand cross-link repair. Science. 2009;326:1698–1701. doi: 10.1126/science.1182372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ben-Yehoyada M, Wang LC, Kozekov ID, Rizzo CJ, Gottesman ME, Gautier J. Checkpoint signaling from a single DNA interstrand crosslink. Mol Cell. 2009;35:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shen X, Do H, Li Y, Chung W-H, Tomasz M, de Winter JP, Xia B, Elledge SJ, Wang W, Li L. Recruitment of Fanconi anemia and breast cancer proteins to DNA damage sites is differentially governed by replication. Mol Cell. 2009;35:716–723. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McHugh P, Sones W, Hartley J. Repair of intermediate structures produced at DNA interstrand cross-links in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3425–3433. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.10.3425-3433.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dendouga N, Gao H, Moechars D, Janicot M, Vialard J, McGowan CH. Disruption of murine Mus81 increases genomic instability and DNA damage sensitivity but does not promote tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7569–7579. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7569-7579.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ciccia A, McDonald N, West S. Structural and functional relationships of the XPF/MUS81 family of proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:259–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.070306.102408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rothfuss A, Grompe M. Repair kinetics of genomic interstrand DNA cross-links: evidence for DNA double-strand break-dependent activation of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:123–134. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.123-134.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bhagwat N, Olsen AL, Wang AT, Hanada K, Stuckert P, Kanaar R, D’Andrea A, Niedernhofer LJ, McHugh PJ. XPF-ERCC1 participates in the Fanconi anemia pathway of cross-link repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6427–6437. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00086-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McCabe KM, Hemphill A, Akkari Y, Jakobs PM, Pauw D, Olson SB, Moses RE, Grompe M. ERCC1 is required for FANCD2 focus formation. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;95:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bergstralh DT, Sekelsky J. Interstrand crosslink repair: can XPF-ERCC1 be let off the hook? Trends Genet. 2008;24:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fekairi S, Scaglione S, Chahwan C, Taylor ER, Tissier A, Coulon S, Dong M-Q, Ruse C, Yates JR, Russell P, Fuchs RP, McGowan CH, Gaillard P-HL. Human SLX4 is a Holliday junction resolvase subunit that binds multiple DNA repair/recombination endonucleases. Cell. 2009;138:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Svendsen JM, Smogorzewska A, Sowa ME, O’Connell BC, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. Mammalian BTBD12/SLX4 assembles a Holliday junction resolvase and is required for DNA repair. Cell. 2009;138:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Muñoz IM, Hain K, Déclais A-C, Gardiner M, Toh GW, Sanchez-Pulido L, Heuckmann JM, Toth R, Macartney T, Eppink B, Kanaar R, Ponting CP, Lilley DMJ, Rouse J. Coordination of structure-specific nucleases by human SLX4/BTBD12 is required for DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2009;35:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Andersen SL, Bergstralh DT, Kohl KP, LaRocque JR, Moore CB, Sekelsky J. Drosophila MUS312 and the vertebrate ortholog BTBD12 interact with DNA structure-specific endonucleases in DNA repair and recombination. Mol Cell. 2009;35:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Loeb LA, Monnat RJ. DNA polymerases and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrg2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yang W, Woodgate R. What a difference a decade makes: insights into translesion DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15591–15598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:317–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yamanaka K, Minko IG, Takata K-I, Kolbanovskiy A, Kozekov ID, Wood RD, Rizzo CJ, Lloyd RS. Novel enzymatic function of DNA polymerase nu in translesion DNA synthesis past major groove DNA–peptide and DNA–DNA cross-links. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:689–695. doi: 10.1021/tx900449u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hinz JM. Role of homologous recombination in DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:582–603. doi: 10.1002/em.20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Muniandy PA, Liu J, Majumdar A, Liu S-t, Seidman MM. DNA interstrand crosslink repair in mammalian cells: step by step. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45:23–49. doi: 10.3109/10409230903501819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sarkar S, Davies AA, Ulrich HD, McHugh PJ. DNA interstrand crosslink repair during G1 involves nucleotide excision repair and DNA polymerase zeta. EMBO J. 2006;25:1285–1294. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang X, Peterson C, Zheng H, Nairn R, Legerski R, Li L. Involvement of nucleotide excision repair in a recombination-independent and error-prone pathway of DNA interstrand cross-link repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:713–720. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.713-720.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shen X, Jun S, O’Neal LE, Sonoda E, Bemark M, Sale J, Li L. REV3 and REV1 play major roles in recombination-independent repair of DNA interstrand cross-links mediated by monoubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13869–13872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hlavin EM, Smeaton MB, Miller PS. Initiation of DNA interstrand cross-link repair in mammalian cells. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:604–624. doi: 10.1002/em.20559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Nojima K, Hochegger H, Saberi A, Fukushima T, Kikuchi K, Yoshimura M, Orelli B, Bishop D, Hirano S, Ohzeki M, Ishiai M, Yamamoto K, Takata M, Arakawa H, Buerstedde J, Yamazoe M, Kawamoto T, Araki K, Takahashi J, Hashimoto N, Takeda S, Sonoda E. Multiple repair pathways mediate tolerance to chemotherapeutic cross-linking agents in vertebrate cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11704–11711. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gillet LCJ, Schärer OD. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian global genome nucleotide excision repair. Chem Rev. 2006;106:253–276. doi: 10.1021/cr040483f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hanawalt P, Spivak G. Transcription-coupled DNA repair: two decades of progress and surprises. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:958–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Muniandy PA, Thapa D, Thazhathveetil AK, Liu S-t, Seidman MM. Repair of laser-localized DNA interstrand cross-links in G1 phase mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27908–27917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.029025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zamble DB, Mu D, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lippard SJ. Repair of cisplatin—DNA adducts by the mammalian excision nuclease. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10004–10013. doi: 10.1021/bi960453+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Min J-H, Pavletich NP. Recognition of DNA damage by the Rad4 nucleotide excision repair protein. Nature. 2007;449:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature06155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Schärer OD. Achieving broad substrate specificity in damage recognition by binding accessible nondamaged DNA. Mol Cell. 2007;28:184–186. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Maillard O, Camenisch U, Blagoev KB, Naegeli H. Versatile protection from mutagenic DNA lesions conferred by bipartite recognition in nucleotide excision repair. Mutat Res. 2008;658:271–286. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhao J, Jain A, Iyer RR, Modrich PL, Vasquez KM. Mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair proteins cooperate in the recognition of DNA interstrand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4420–4429. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhang Y, Wu X, Guo D, Rechkoblit O, Geacintov NE, Wang Z. Two-step error-prone bypass of the (+)- and (−)-trans-anti-BPDE-N2-dG adducts by human DNA polymerases eta and kappa. Mutat Res. 2002;510:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bessho T, Mu D, Sancar A. Initiation of DNA interstrand cross-link repair in humans: the nucleotide excision repair system makes dual incisions 5′ to the cross-linked base and removes a 22- to 28-nucleotide-long damage-free strand. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6822–6830. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mu D, Bessho T, Nechev LV, Chen DJ, Harris TM, Hearst JE, Sancar A. DNA interstrand cross-links induce futile repair synthesis in mammalian cell extracts. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2446–2454. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.7.2446-2454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Martin LP, Hamilton TC, Schilder RJ. Platinum resistance: the role of DNA repair pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1291–1295. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Spanswick VJ, Hartley JM, Hartley JA. Measurement of DNA interstrand crosslinking in individual cells using the single cell gel electrophoresis (Comet) assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;613:267–282. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-418-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt ANJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NMB, Jackson SP, Smith GCM, Ashworth A. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]