Abstract

To determine whether macrophage differentiation involves increased uptake of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, we assessed the expression and function of its transporter SVCT2 during phorbol ester-induced differentiation of human-derived THP-1 monocytes. Induction of THP-1 monocyte differentiation by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) markedly increased SVCT2 mRNA, protein, and function. When ascorbate was present during PMA-induced differentiation, the increase in SVCT2 protein expression was inhibited, but differentiation was enhanced. PMA-induced SVCT2 protein expression was blocked by inhibitors of protein kinase C (PKC), with most of the affect due to the PKCβI and βII isoforms. Activation of MEK/ERK was sustained up to 48 h after PMA treatment, and the inhibitors completely blocked PMA-stimulated SVCT2 protein expression, indicating an exclusive role for the classical MAP kinase pathway. However, inhibitors of NF-κB activation, NADPH oxidase inhibitors, and several antioxidants also partially prevented SVCT2 induction, suggesting diverse distal routes for control of SVCT2 transcription. Both known promoters for the SVCT2 were involved in these effects. In conclusion, PMA-induced monocyte-macrophage differentiation is enhanced by ascorbate and associated with increased expression and function of the SVCT2 protein through a pathway involving sustained activation of PKCβI/II, MAP kinase, NADPH oxidase, and NF-κB.

Keywords: ascorbate transport, SVCT2, protein kinase C, MAPK, NF-κB

Introduction

Macrophages are a crucial component of the inflammatory response, whether this is beneficial, as in response to bacterial infection, or harmful, as in atherosclerosis and certain autoimmune processes. Macrophages are derived from short-lived circulating blood monocytes following recruitment of the latter into the sub-endothelial space. Macrophage differentiation from monocytes varies with the tissues involved and depends on complex interactions with growth factors, cytokines, matrix proteins, and other cells [1,2]. One factor heretofore largely neglected in the macrophage differentiation process is vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. Ascorbate has been shown to enhance differentiation of osteoblast precursors [3], neuronal stem cells [4], axon-related Schwann cells [5], HL-60 cells [6], and a skeletal muscle cell line [7]. The ascorbate might also play a role in monocyte differentiation is suggested by the results of a study in which scorbutic guinea pigs challenged with an intraperitoneal injection of mineral oil developed only 25% the number of macrophages as did animals on an ascorbate-sufficient diet [8]. Compared to cells from ascorbate-replete animals, these macrophages were also less mature and had impaired migration, although not phagocytosis. If ascorbate is involved in macrophage differentiation or survival, then macrophages should have efficient mechanisms for maintaining intracellular ascorbate.

Both monocytes and macrophages contain high intracellular ascorbate concentrations compared to other related cell types. For example, ascorbate concentrations in freshly isolated human monocytes are 4–6 mM [9,10], which is more than twice that present in circulating neutrophils, and about 80-fold greater than the 40–50 µM ascorbate concentrations in plasma [9]. Peritoneal macrophages derived from thioglycollate-treated mice, even though activated, also have ascorbate concentrations of 3 mM [11]. At least one role for this intracellular ascorbate is to protect the cells from oxidant damage [12]. For example, macrophage phagocytosis progressively decreases intracellular ascorbate, whereas increasing intracellular ascorbate decreases ROS and preserves α-tocopherol [11].

High intracellular ascorbate concentrations in macrophages are maintained by the sodium- and energy-dependent SVCT2 transporter [11], one of the two isoforms of this transporter that have been cloned [13]. Ascorbate can also enter cells in its two-electron oxidized form, which is often termed dehydroascorbate (DHA). DHA forms a bicyclic hemiketal in solution that is transported on the GLUT-type glucose transporter [14]. Once inside cells, DHA is rapidly reduced to ascorbate, which it is trapped within cells because of the hydrophilic nature and negative charge. Although DHA uptake and reduction efficiently recycles oxidized ascorbate and prevents loss of ascorbate due to the short half-life of DHA in physiologic fluids, it likely contributes little to maintaining the concentration gradient of ascorbate across the plasma membrane. Support for this conclusion is that human erythrocytes, which lack the SVCT2 [15] but rapidly recycle ascorbate from DHA [16], have intracellular ascorbate concentrations the same as those in plasma [9]. Even more compelling evidence for the importance of the SVCT2 in maintaining intracellular ascorbate is the SVCT2 knockout mouse [17], which has very low ascorbate concentrations in brain, liver, lung, and other tissues, and which dies at birth.

Despite its importance for maintaining intracellular ascorbate, little is known about regulation of the SVCT2. The human protein encodes a 650 amino acid membrane protein that crosses the plasma membrane 12 times and contains potential intracellular protein kinase A and C phosphorylation sites [13]. The latter are probably involved in post-translational regulation of the SVCT2, since ascorbate transport is acutely stimulated by cyclic AMP analogs [18] and by protein kinase C (PKC) activation [19]. Phorbol ester or thrombin stimulation of human platelets increased SVCT2 protein expression and function [20]. This effect was due to increases in translation of existing SVCT2 mRNA, since platelets lack nuclei and this transcriptional machinery, and since no changes were evident in platelet SVCT2 mRNA. In nucleated cells a variety of agents enhance SVCT2 expression at the level of mRNA, protein, and function. In some instances this is not related to cell differentiation, such as when induced by glucocorticoids [21], epidermal growth factor [22], or hydrogen peroxide [23], whereas in others it accompanies cell differentiation, such as with zinc [24] and calcium/phosphate ions [25]. These results support SVCT2 regulation at both the transcriptional and translational levels, but do not define the signal transduction pathway(s) involved, or define a role for the SVCT2 in cell differentiation.

In the present work we evaluated the transcriptional/translational regulation of the SVCT2 during differentiation of human THP-1 monocytes to macrophages, since these cells express established monocyte-macrophage markers on differentiation [26,27], and since they have been extensively studied as a model of monocytic differentiation to macrophages with relevance to inflammation, infection, and atherosclerosis [28,29]. Monocyte-to-macrophage conversion of these cells is typically induced by treatment with the tumor-promoting agent phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), which activates the PKC signaling pathway in a number of cell types [30–32]. We found that ascorbate enhanced PMA-induced THP-1 monocyte differentiation, that PMA-induced differentiation caused a large increase in SVCT2 message, protein, and function, and that the latter responses are dependent on the PKCβI/II isoforms acting through pathways involving B-Raf, MEK/ERK, and NF-κB.

Materials and Methods

Materials

PMA, actinomycin D, GF109203x, GW 5074, PD 98059, Trolox, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase-polyethylene glycol (PEG-catalase), N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), apocynin, and diphenylene iodonium (DPI) were from Sigma/Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Bryostatin 2, Gö6983, Gö6976, PKCβ inhibitor, PKCβII/EGFR inhibitor (CGP53353), ZM 336372, FR180204, NF-κB Activation Inhibitor and IKK Inhibitor VII were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The B-Raf inhibitor SB-590885 was kindly provided by GlaxoSmithKline, PLC (Stevenage, United Kingdom). The antibodies for SVCT2 (S-19), SVCT1 (N-20, H-78), p-ERK1/2 (E-4), PKCβII (F-7), IκB-α (C-21) and actin (I-19) used in immunoblots were supplied by Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Suppliers of additional antibodies were as follows: phospho-PKCβII (Thr641) (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and phospho-PKC (pan) (βII Ser660) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Inc. supplied the L-[1-14C]ascorbic acid (specific activity 4 mCi/mmol), which was dissolved in deionized water containing 0.1 mM acetic acid and stored in multiple aliquots at −20 °C until use.

Cell culture and differentiation

THP-1 human myeloid leukemia cells were obtained from the ATCC and were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Monocyte suspensions were typically differentiated into macrophages by a 72-h exposure to 100 nM PMA. PMA treatment resulted in a phenotype characterized by adherence to the culture plate, and cessation of proliferation (data not shown).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL reagent (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), and 2 µg was primed with random hexamers and reverse transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) in a final volume of 20 µl. One microliter of this mixture was amplified in a 25-µl reaction using Advantage 2 PCR kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide. The amplification parameters and primers for SVCT2, CD11b, CD14 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) are provided in Table I.

Table I.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences and PCR conditions for regular RT-PCR

| PCR condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Primer sequences(5’ to 3’) | Denaturation | Annealing | Elongation | cycle no. |

|

| SVCT2 | F | GAT GCC ATG TGT GTG GGG TA | 95°С | 55°С | 72°С | 40 |

| R | TAT TGT CAG CAT GGC AAT GC | 30 sec | 30 sec | 30 sec | ||

| P1/exon 1a |

F | TCA GAC TCA GGG TGA AGG ACA CCA | 95°С | 60°С | 72°С | 40 |

| R | ACC ACC GGA AGA GTG AAG AAA GCT GG | 30 sec | 30 sec | 30 sec | ||

| P2/exon 1b |

F | AAC CAC GCG AGC TGC AGC CAG | 95°С | 55°С | 72°С | 40 |

| R | ACC ACC GGA AGA GTG AAG AAA GCT GG | 30 sec | 30 sec | 30 sec | ||

| CD11b | F | CCC CCA GGT CAC CTT CTC CG | 95°С | 60°С | 72°С | 29 |

| R | GCT CTG TCG GGA AGG AGC CG | 30 sec | 30 sec | 30 sec | ||

| CD14 | F | CGA GGA CCT AAA GAT AAC CGG C | 95°С | 60°С | 72°С | 29 |

| R | GTT GCA GCT GAG ATC GAG CAC | 30 sec | 30 sec | 30 sec | ||

| G3PDH | F | TCT TTT GCG TCG CCA GCC GAG C | 95°С | 68°С | 72°С | 25 |

| R | CCT GCA AAT GAG CCC CAG CCT TC | 30 sec | 30 sec | 30 sec | ||

Assay of cell adhesion

To assess cell adhesion, THP-1 monocytes were treated for 3 days in culture with 0–100 nM PMA in the absence or presence of 100 µM ascorbate. Non-adherent cells were removed by two gentle rinses with PBS. The adherent cells were then completely removed from the plate by a 5 min treatment with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution. The released cells were counted using a hemocytometer.

Assay of ascorbate transport

Ascorbate transport was measured in differentiated THP-1 monocytes following 3 days of treatment with 100 nM PMA. The cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/well in 6-well plates. Undifferentiated cells were prepared to the same cell number in suspension for comparison of transport rates. Prior to the assay, cells were rinsed with cell incubation buffer (15 mm Hepes, 135 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 0.8 mm MgCl2), either directly for differentiated cells on the plates, or by centrifugation (1,000 x g, 5 min) for non-adherent undifferentiated cells. The transport assay was carried out by incubation of the cells at 37 °C in 1 ml of the same medium that contained 2–200 µM L-[1-14C]ascorbic acid, 0.5 mM reduced glutathione and 30 mM 3-O-methylglucose. Glutathione was included to prevent the oxidation of ascorbate, and the glucose analog was included to block any uptake of any remaining DHA on glucose transporters [11]. Uptake was stopped at 20 min or as noted by rinsing the cells with three times in ice-cold PBS. Cells were dissolved in 1 mL of 1 M NaOH and the incorporated radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Transport kinetic constants (Km and Vmax) were calculated from initial rates of transport at various concentrations of ascorbate by fitting the data to a double reciprocal plot. Data represent means ± SD of two experiments with each determination done in duplicate.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer that contained 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 (v/v), 0.5% deoxycholic acid (w/v), 0.1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (pH 8.0). Cytosolic fractions were prepared from cells treated with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 µg/ml digitonin). After centrifugation (12,000 x g, 15 min), soluble cytosolic fractions were removed and the remaining pellets were treated for 30 min at 4 °C with the lysis buffer supplemented with 1% of Triton X-100. The samples were again centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C and the soluble supernatant containing the membrane fraction was removed. The remaining particulate fraction was then extracted by boiling for 5 min in a 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) buffer supplemented with 2.5% SDS and 10% glycerol. To prevent proteolysis and dephosphorylation, these buffers also contained a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 1 (Sigma/Aldrich). Proteins were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 7.5% polyacrylamide gels and were then electro-transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated for 2 h at room temperature (overnight at 4 °C for SVCT2) with primary antibody in the following dilutions: 1:200 dilution for SVCT2 (S-19), SVCT1 (N-20, H-78), p-ERK1/2 (E-4), PKCβII (F-7), IκB-α (C-21) and actin (I-19); 1:1000 dilution for phospho-PKCβII (Thr641) and phospho-PKC (pan) (βII Ser660) antibody. After three rinses in 1x PBS-Tween 20, the membranes were incubated at room temperature for 2 hours with a 1:10,000 dilution of a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) and detection was carried out with ECL (Amersham, United Kingdom).

Competition experiments were carried out by incubating the primary antibody with a 100-fold molar excess of blocking peptide for 3 h at room temperature before immunoblotting.

Data analysis

Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance with post-hoc testing using the software program Sigma Stat 2.0 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Significance was based on a P value of <0.05.

Results

PMA induces SVCT2 expression in THP-1 monocytes during macrophage differentiation

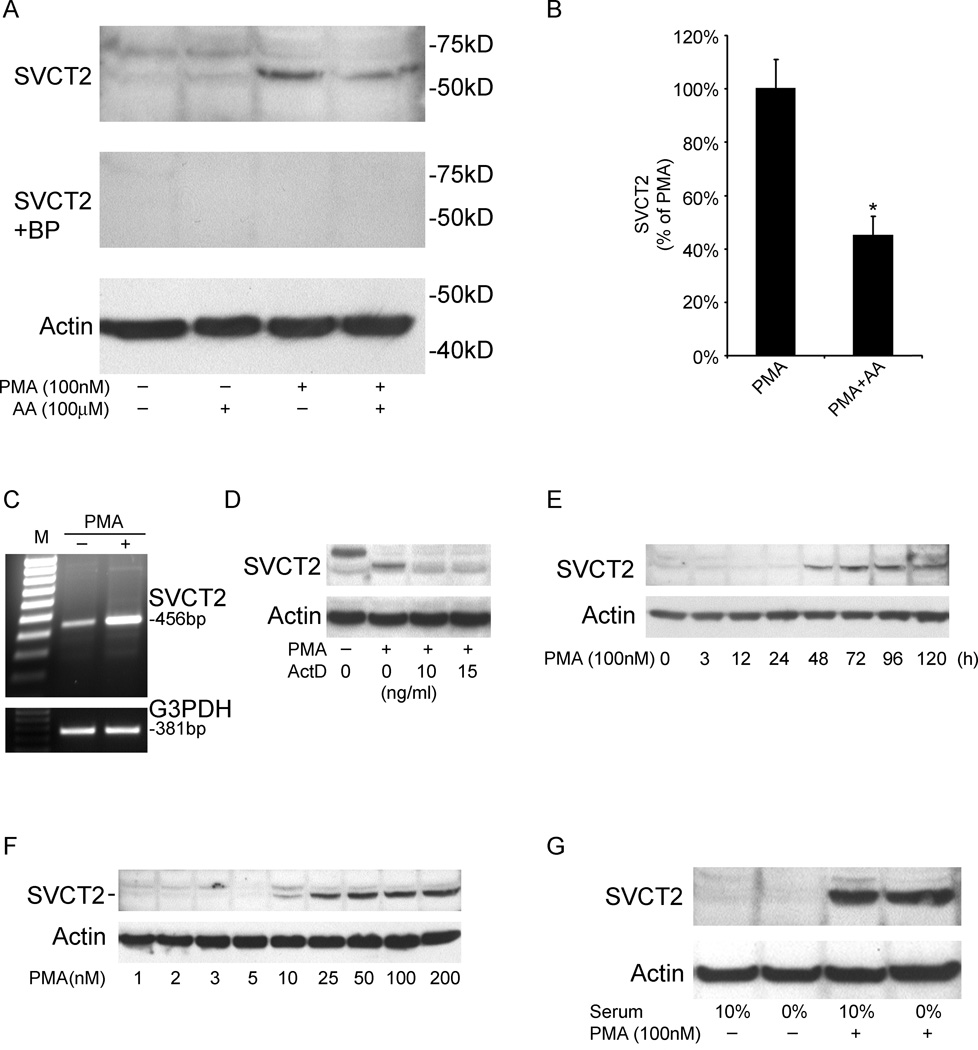

To assess effects of such differentiation on SVCT2 expression, undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes were cultured for 3 days with 100 nM PMA followed by immunoblot analysis. The SVCT2 was identified on electrophoresis as a band with an apparent molecular weight of about 65 kDa (Fig. 1A). In undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes this band was faint, but was strongly induced by PMA. Inclusion of 100 µM ascorbate at the beginning and daily during the 3–5 day PMA treatment significantly decreased SVCT2 induction by 55% (Fig. 1B). Another band of 75 kDa was often observed in undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes, but was usually decreased by PMA treatment. Competition studies performed with the peptide to which the antibody was made abolished labeling of both bands, leaving open the possibility that the 75 kDa band is a larger isoform of the transporter with differential regulation by PMA. PMA-induced expression of the SVCT2 at the mRNA level was also confirmed by RT-PCR with detection of a 456 bp product (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the SVCT1 was not detected either by RT-PCR or by immunoblotting using both N- and C-terminal-specific antibodies (data not shown). We next determined whether the induction of SVCT2 expression by PMA was due to increased rates of transcription using actinomycin D, which inhibits DNA-primed RNA polymerase activity. As shown in Fig. 1D, actinomycin D abolished PMA-mediated SVCT2 protein expression. PMA stimulated SVCT2 protein expression in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1E and F). Increased expression was apparent within 48 h after addition of 100 nM PMA, was maximal at 3–4 days of PMA exposure (Fig. 1E). Increased SVCT2 expression after 3 days in culture was evident at a PMA concentration as low as 10 nM and was maximal at 100 nM PMA (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

PMA induces SVCT2 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. (A) Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of a single addition of 100 nM PMA or daily additions of 100 µM ascorbate (AA) as noted for 3 days and then were prepared for immunoblotting using antibodies specific for SVCT2 or actin as described in Materials and methods. The top panel shows SVCT2 immunostaining, the middle panel (SVCT2+BP) shows a competition study with the SVCT2 blocking peptide, and the bottom panel shows staining for actin. The latter was included as a control to confirm equivalent protein loading in each lane. Locations of molecular weight markers and the bands corresponding to the SVCT2 are noted. (B) Combined results from 6 experiments of ascorbate effects on PMA-induced SVCT2 protein expression, expressed as percentage of PMA treatment results, with an asterisk indicating P<0.001 versus PMA alone. (C) Cells were treated with or without 100 nM PMA for 3 days as noted, followed by amplification of mRNA by RT-PCR and ethidium bromide staining. G3PDH staining is included as a control. (D) THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with actinomycin D (ActD) for 30 min prior to a 3 day treatment with PMA and harvesting of cells for immunoblotting of the SVCT2 (top panel) and actin (bottom panel). (E) Time course of PMA (100 nM) stimulation of SVCT2 expression was measured by immunoblotting of the SVCT2 (top panel), along with actin control (bottom panel). (F) Concentration-dependence of PMA-stimulated SVCT2 expression (top panel) and actin (bottom panel) were measured by immunoblotting of cell extracts after 3 days in culture with the indicated concentration of PMA. (G) Cells were maintained in 0% serum for 2 d, and then supplemented with 100 nM PMA for additional 3 d followed by SVCT2 immunoblotting.

Both THP-1 monocytes and macrophages were typically cultured in the presence of 10% fetal calf serum, which was associated with low SVCT2 protein expression (Fig. 1A). It is possible that the presence of growth factors and cytokines in the 10% fetal calf serum could modify PMA induction of SVCT2. As shown in Fig. 1G, serum deprivation did not affect SVCT2 expression after 3 d of PMA induction. This indicates that the PMA effects on SVCT2 expression were independent of serum factors.

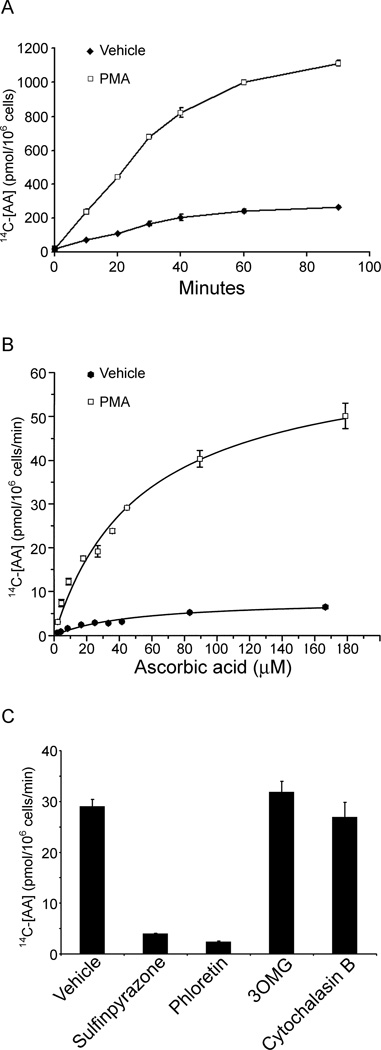

PMA-induced THP-1 monocyte differentiation increases ascorbate transport

To determine if increased SVCT2 protein expression has functional consequences, effects of PMA-induced differentiation on rates of ascorbate transport were determined. The time course of ascorbate transport in both undifferentiated and differentiated cells was linear for at least 40 min and was increased in the differentiated cells (Fig. 2A). Measurement of initial rates of transport over a range of extracellular ascorbate concentrations showed that transport was saturable in both cell types (Fig. 2B). For undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes the apparent Km was 48.5 ± 10.9 µM with a Vmax of 8.1 ± 0.8 pmol/106 cells/min; for differentiated THP-1 monocytes, the apparent Km was 53.6 ±7.3 µM with a Vmax of 64.3±3.9 pmol/106 cells/min. These results indicate that PMA-induced differentiation of THP-1 monocytes increased the transport Vmax by approximately eight-fold over the vehicle, which is in agreement with the relative increase in SVCT2 protein determined by immunoblotting. On the other hand, PMA treatment did not change the Km of ascorbate transport. Further evidence for that the SVCT2 mediated this transport was that it was almost completely blocked by sulfinpyrazone and phloretin (Fig. 2C), two known inhibitors of sodium- and energy-dependent ascorbate transport in other cells. On the other hand, the glucose transport inhibitors 3-O-methylglucose (3OMG) and cytochalasin B were without effect on rates of ascorbate transport.

Fig. 2.

Ascorbate transport in undifferentiated and differentiated THP-1 monocytes. (A) Time course of uptake of 50 µM L-[1-14C]ascorbic acid was measured in undifferentiated cells treated with vehicle alone and cells that had been differentiated by 3 days of treatment with 100 nM PMA. Data represent the mean ± SD of three experiments. (B) Concentration-response curves for the transport of radiolabeled ascorbate were measured over 20 min at 37 °C in undifferentiated cells (treated with Vehicle alone) or in cells differentiated as noted in (A) by PMA. (C) Transport inhibitor effects on radiolabeled ascorbate transport were measured in PMA-differentiated cells for 30 min at 37 °C without/with addition of sulfinpyrazone (1 mM), phloretin (100 µM), 3OMG (30 mM), or cytochalasin B (10 µM). Data represent the mean ± SD of two experiments.

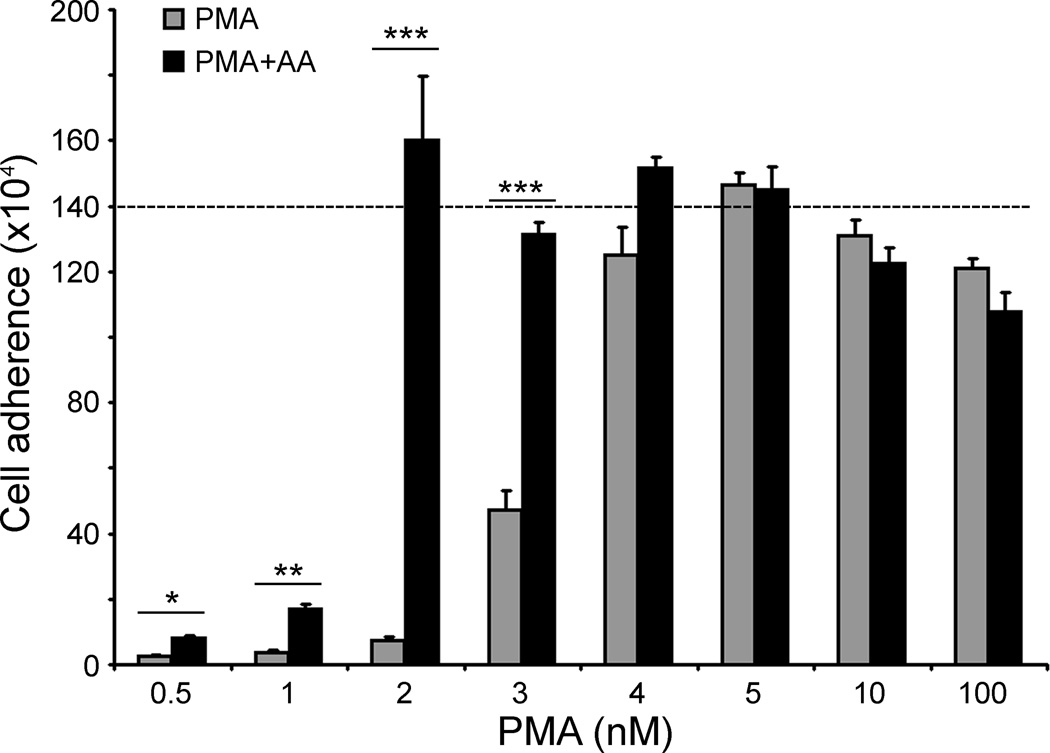

Ascorbate promotes cell adhesion and conversion to macrophage morphology during PMA-induced differentiation

PMA-induced differentiation of THP-1 monocytes is characterized by increased cell adherence, loss of proliferation, and assumption of a spindle-shaped phenotype [29]. As shown Fig. 3, culture of the same initial number of THP-1 monocytes with increasing concentrations of PMA caused more cells to convert from a rounded shape with poor adherence to a macrophage-like morphology (large cells, strongly adherent with spindle-like shapes). Although ascorbate alone had no effect on adhesion or cell morphology (data not shown), after culture with both ascorbate (100 µM) and increasing concentrations of PMA, more cells adhered to the plate and became spindle-shaped than with PMA alone. The effect of ascorbate on cell adhesion was quantified and shown to be most apparent at sub-maximal concentrations of PMA (Fig. 3). The data are shown relative to the initial number of plated cells (dashed line), rather than as a ratio of adherent/non-adherent cells, since the latter is confounded by continued proliferation at low PMA concentrations. In the absence of PMA, THP-1 cell numbers increased about 4-fold over 3 days in culture.

Fig. 3.

PMA-induced cell adhesion is enhanced by ascorbate. Cells (1.4 × 106 per well) were cultured for 3 days with the indicated concentration of PMA in the absence or presence of daily additions of 100 µM ascorbate and adhesion was quantified as described under Materials and methods. Data are mean ± SD of 3 determinations from an experiment representative of 4 performed. Statistical comparison between cells pretreated or not with ascorbate is shown as follows: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

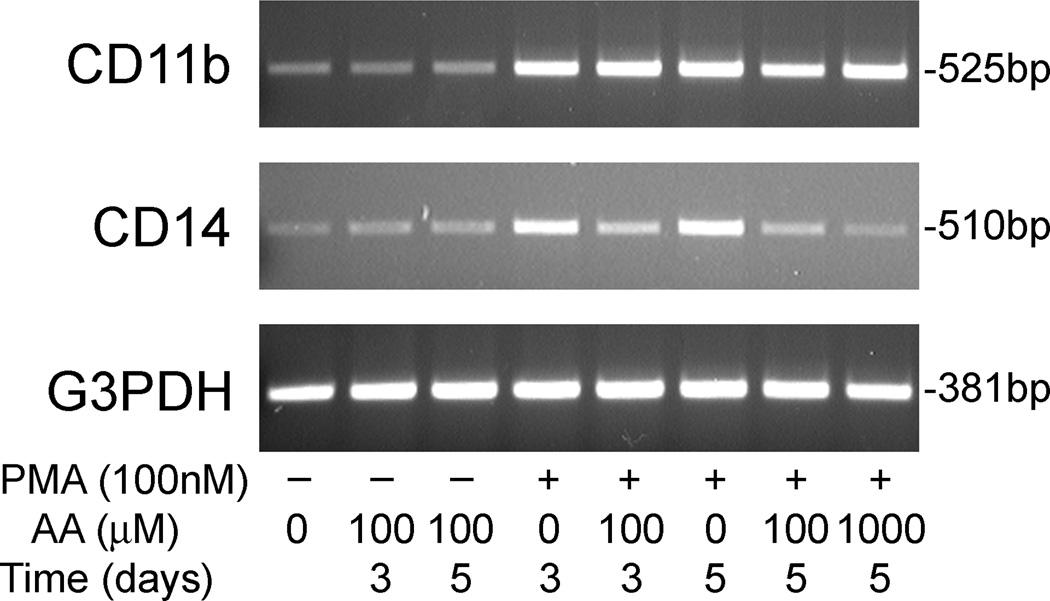

PMA-induced differentiation in THP-1 monocytes is accompanied by increased expression of the macrophage markers CD11b and CD14 [29]. In agreement, we found that treating THP-1 monocytes with 100 nM PMA over 3–5 days in culture increased mRNA of both markers, as noted in the top two panels of Fig. 4. Addition of ascorbate alone was without effect on either differentiation marker over the same time period. When cells were treated with both PMA and ascorbate, CD11b expression was unchanged compared to PMA alone (Fig. 4, top panel), but expression of CD14 was decreased, especially at 1 mM ascorbate (Fig. 4, middle panel).

Fig. 4.

PMA and ascorbate effects on macrophage differentiation markers. THP-1 monocytes were treated in culture for the times indicated with PMA and/or ascorbate at the concentrations indicated, followed by RT-PCR analysis of total RNA for CD11b (top panel) and CD14 (middle panel). The bottom panel shows G3PDH mRNA to confirm equal loading of the gel lanes with cell material. Results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments.

The results thus far show that PMA-induced macrophage differentiation of THP-1 monocytes markedly increases expression and function of the SVCT2 and that certain aspects of such differentiation are modified by ascorbate. We next sought to determine the molecular mechanism by which PMA increased SVCT2 transcription and expression, especially as dependent on the protein kinase C and MAP kinase pathways.

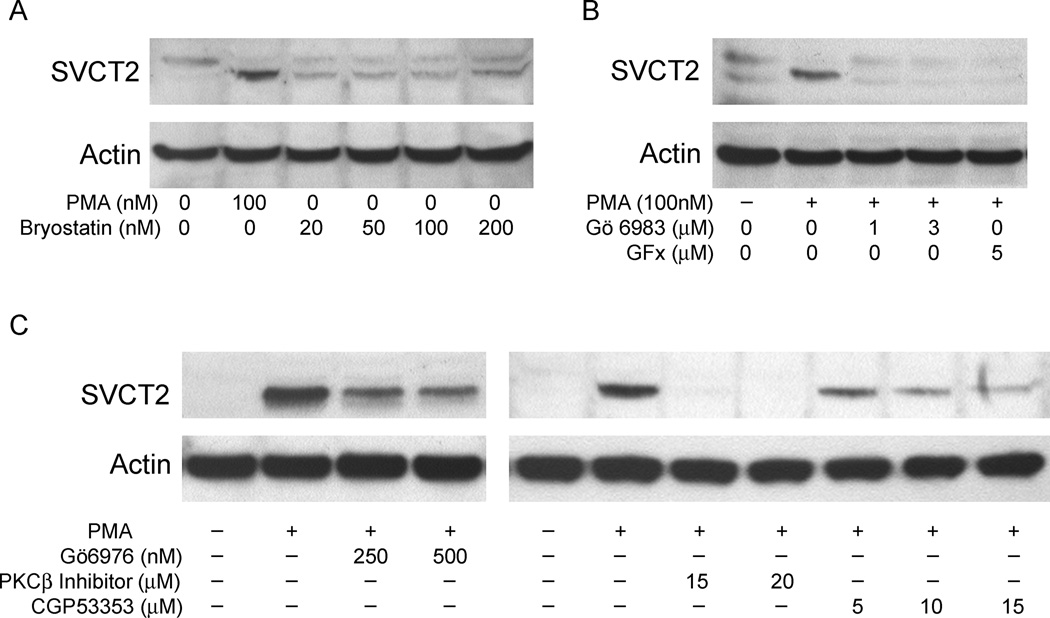

PMA activates PKC and its βI/βII isoforms in THP-1 monocytes

PMA is known to stimulate PKC by acting as an analog of diacylglycerol. Several agents were used to confirm that PKC activation was required for PMA-stimulated SVCT2 expression. Bryostatin 2, which is a competitive PKC agonist, induced SVCT2 protein expression over 3 days of treatment in culture at concentrations as low as 20 nM, although expression was not as high as an equal concentration of PMA (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, PKC inhibitors with broad isoform specificity blocked PMA-stimulated SVCT2 expression. As shown in Fig. 5B, SVCT2 induction by PMA was completely blocked by 1 µM Gö6983 and by 5 µM GF109203x (GFx). These agents inhibit the PKC isoforms α, βI, βII and δ in THP-1 monocytes [33]. Gö6976, which selectively inhibits PKC isoforms α, βI and µ at the concentrations used, partially blocked the induction of the SVCT2 by PMA (Fig. 5C, left panel). An inhibitor that selectively inhibits the βI and βII isoforms of PKC, noted in the right panel of Fig. 5C as PKCβ, completely blocked PMA-induced SVCT2 expression at a concentration of 15 µM. On the other hand, the PKCβII-specific inhibitor CGP53353 also decreased, but did not abolish, PMA-induced SVCT2 expression (Fig. 5C, right panel). Together, these results indicate involvement of PKCβI and βII in PMA-dependent SVCT2 induction.

Fig. 5.

PMA activates PKC and its βI/II isoforms in THP-1 monocytes. (A) Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of PMA or the PKC agonist bryostatin 2 as noted for three days in culture and taken for SVCT2 immunoblotting. (B) Cells were pretreated for 30 min with the indicated concentrations of the selective PKC inhibitors Gö6983 or GF109203x (GFx), and then treated with PMA (100 nM) for 3 days before SVCT2 immunoblotting. (C) Cells were treated for 3 days with 100 nM PMA along with the indicated concentrations of a Ca2+-dependent PKC inhibitor (Gö6976), an inhibitor of both PKCβI and PKCβII, (PKCβI/II), or a PKCβII-specific inhibitor (CGP53353) followed by extraction and immunoblotting for the SVCT2. The gels shown are representative of 2 gels with each treatment.

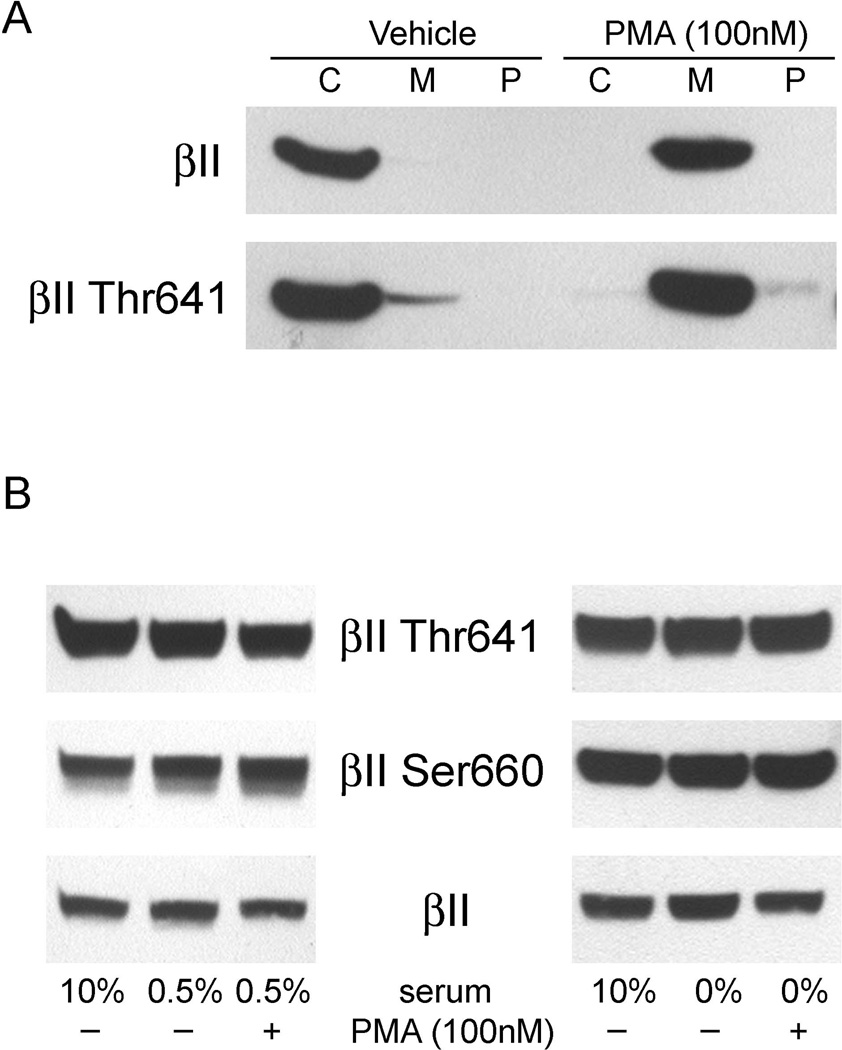

Effects of PMA on the phosphorylation status of PKCβ

To further evaluate the activation of PKCβ, we compared the distribution of PKCβII, among the cytosolic, membrane, and SDS/glycerol extractable particulate protein fractions isolated from undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes that were acutely stimulated with PMA. After only 1 h of stimulation with 100 nM PMA, translocation of PKCβII as well as PKCβII phosphorylated on Thr641 from the cytosolic to the membrane fraction was observed, reflecting activation of this enzyme (Fig. 6A). PMA to activation of PKC in other cells requires phosphorylation of Thr641 and Ser660 [34,35] and several other studies have also implicated the involvement of PMA in the phosphorylation of PKC, although this has not been shown for monocytes. As shown in Fig. 6B, PKCβII showed substantial basal phosphorylation on both Thr641 and Ser660 that was unaffected by PMA. Basal PKCβII phosphorylation was unaffected by culture of the cells for 3 days in low-serum conditions (0.5%) or adapted over 2 days to lack of serum before stimulation (Fig. 6B). Thus, acute stimulation with PMA did not significantly increase PKCβII phosphorylation, indicating that PKCβII is constitutively phosphorylated at Thr641 and Ser660, and that phosphorylation is not an immediate activation step in THP-1 monocytes.

Fig. 6.

Constitutive phosphorylation of PKCβII in unstimulated THP-1 monocytes. (A) THP-1 monocytes were stimulated for 1 h with 100 nM PMA. Cytosolic (C), membrane (M) and particulate (P) protein fractions were isolated from the cells and were tested for the presence of PKCβII by immunoblotting. (B) Cells were maintained in 0.5% serum for 72 hours or in 0% serum for 2 days, and then treated with 10%, 0.5% or 0% serum in the presence or absence of PMA for 30 min. The phosphorylation status of Thr641 and Ser660 in PKCβII and total PKCβII (βII) were determined by immunoblot of the phosphoproteins in whole cell extracts.

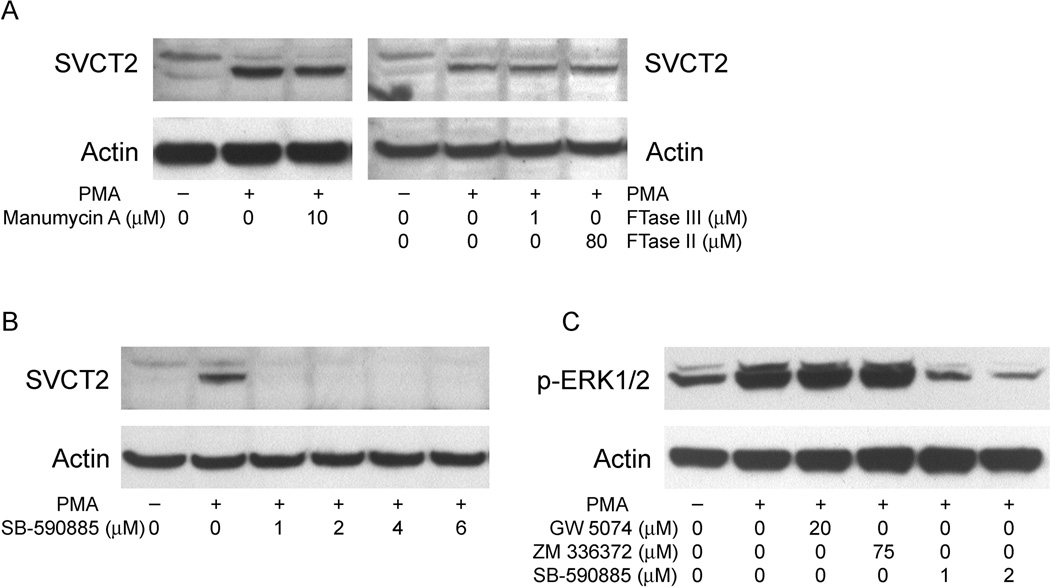

PMA/PKC activates B-Raf in a Ras-independent manner

Many of the downstream effects of PKC activation are mediated through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways. PMA acting through PKC can activate the classical MAPK pathway through Ras-dependent or -independent pathways. To determine whether PMA-induced SVCT2 expression is dependent on Ras in THP-1 monocytes, three Ras inhibitors (manumycin A, FTase Inhibitor II and FTase Inhibitor III) were employed. As shown in Fig. 7A, PMA-stimulated SVCT2 induction was not affected by any of the inhibitors. Thus, PMA-induced SVCT2 expression appears to be independent of Ras in these cells.

Fig. 7.

Induction of SVCT2 is dependent on B-Raf, but not Ras. In all experiments cells were pre-treated for 30 min with the respective inhibitors before addition of 100 nM PMA for 3 d in culture. THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with Ras inhibitors manumycin A, FTase Inhibitor II and FTase Inhibitor III (A), or the B-Raf inhibitor SB-590885 (B). Whole-cell lysates were extracted and analyzed for SVCT2 by immunoblotting. (C) Cells were pretreated with Raf inhibitors for 30 min prior to incubation with 100 nM PMA for 1 h. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis with an antibody specific for phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2).

We next determined the role of Raf kinases in SVCT2 induction. Raf kinases are phosphorylated and activated by PKC, leading into the MAPK pathway, which involves subsequent phosphorylation and activation of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2. To evaluate the involvement of Raf kinases, we treated cells with specific inhibitors of Raf. As shown in Fig. 7B, inhibition of B-Raf with 1 µM SB-590885 completely blocked SVCT2 induction. If PMA induces the SVCT2 through the MAPK pathway, then phosphorylation of ERK1/2 should occur and inhibition of the respective Raf should also block ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Although inhibition of PMA-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was not observed for two c-Raf inhibitors (Fig. 7E, lanes 3 and 4), it was evident when B-Raf was inhibited (Fig. 7E, lanes 5 and 6). This indicates that the PMA/PKC cascade is mediated by B-Raf activation.

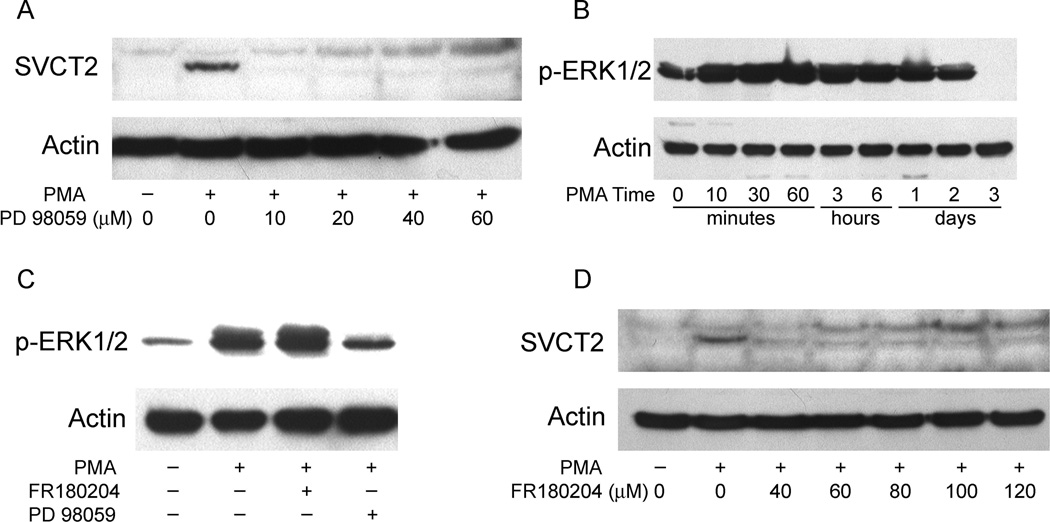

MAPK pathway is involved in PMA-induced SVCT2 expression

To test the role of the “classical” MAPK pathway in PMA-induced SVCT2 expression, we pretreated THP-1 monocytes for 30 min with increasing concentrations of the highly selective MAPK kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD 98059, followed by PMA (100 nM) for 3 days. As shown in Fig. 8A, PD98059 completely abolished PMA-induced SVCT2 induction at a concentration of 10 µM and also prevented differentiation by PMA (data not shown). Since MEK activation of ERK1/2 involves phosphorylation on its threonine and tyrosine residues, we evaluated the ability of PMA to phosphorylate ERK1/2. PMA treatment of THP-1 monocytes caused rapid ERK1/2 phosphorylation over 10 min, which was sustained until day 2 in culture, but then decreased to zero at day 3 (Fig. 8B). The PMA agonist bryostatin 2 can also induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (data not shown). As shown in lane 3 of Fig. 8C, PMA-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was not affected by inhibition of its kinase activity with the ERK inhibitor FR180204 (also known as ERK inhibitor II) [36], but was markedly inhibited when cells were treated with the MEK inhibitor PD 98059 (4th lane, Fig. 8C). Further, inhibition of the kinase activity of ERK1/2 by FR180204 completely abolished PMA-induced SVCT2 expression (Fig. 8D). Taken together, these results support a role for sustained ERK1/2 activation in the MAPK pathway as a key component of SVCT2 induction.

Fig. 8.

MAPK pathway inhibition abolishes SVCT2 expression. (A) THP-1 monocytes were pretreated for 30 min with the MEK inhibitor PD 98059 before incubation with 100 nM PMA for 3 days and immunoblotting of the SVCT2 in whole-cell lysates. (B) Cells were treated with 100 nM PMA for different time intervals, followed by assay of ERK1/2 phosphorylation as noted above. (C) Cells were pretreated with the ERK inhibitors FR180204 (60 µM) or PD 98059 (20 µM) for 30 min before incubation with 100 nM PMA for 60 min. Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates was carried out using the p-ERK1/2-specific antibody. (D) Cells were pretreated for 30 min with the ERK inhibitor FR180204 before a 3 d exposure to 100 nM PMA and immunoblotting of the SVCT2.

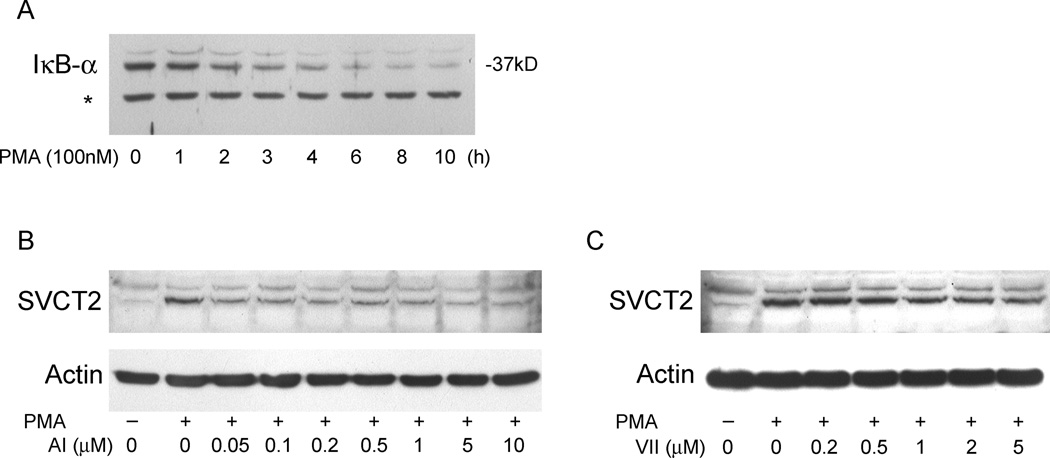

NF-κB pathway is involved in PMA-induced SVCT2 expression

The NF-κB pathway has been shown to be activated downstream of MEK/ERK [37,38]. To confirm this in THP-1 monocytes, PMA-induced degradation of IκB-α was investigated. As shown in Fig. 9A, incubation of THP-1 monocytes with PMA for 5 h or more led to significant proteolysis of IκB-α. To further determine whether NF-κB plays a role in the PKC-mediated induction of SVCT2, we pretreated THP-1 monocytes with an NF-κB activation inhibitor (AI) and with IKK inhibitor VII, followed by PMA treatment. Both NF-κB pathway inhibitors attenuated PMA-induced SVCT2 expression over 3 days of culture, although inhibition was not complete with either agent (Fig. 9B and C).

Fig. 9.

Involvement of NF-κB in PMA-mediated SVCT2 expression in human THP-1 monocytes. (A) PMA-induced degradation of IκB-α was investigated. THP-1 monocytes were stimulated for different times with 100 nM PMA. Cytosolic extracts were analyzed. The asterisk indicates a non-specific band as a loading control. (B) and (C) Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of NF-κB Activation Inhibitor (AI) or IKK Inhibitor VII (VII) for 30 min before incubation with 100 nM PMA for 3 d followed by immunoblotting of the SVCT2.

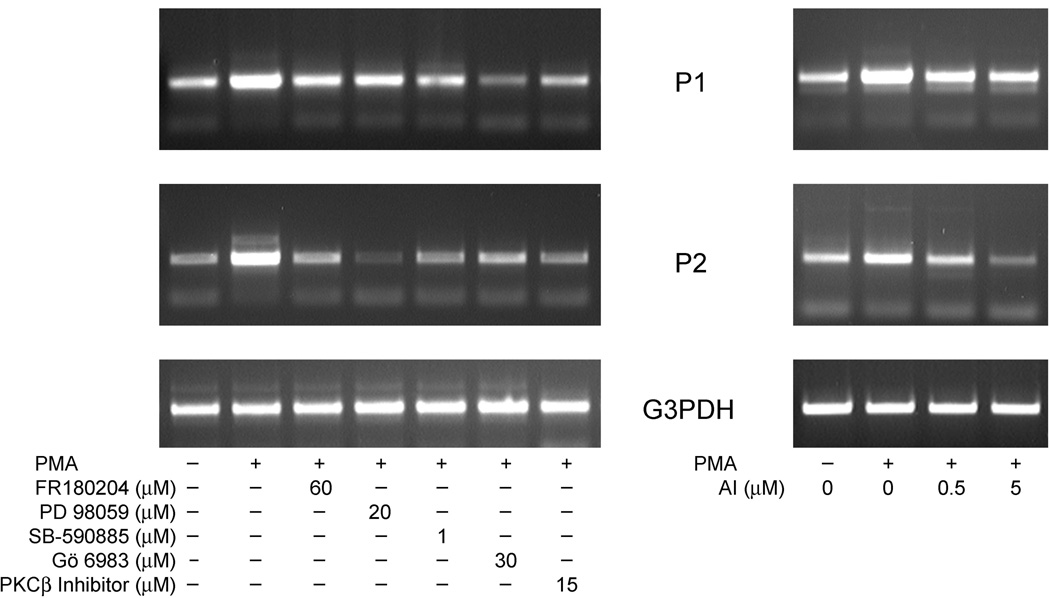

Role of SVCT2 promoter variants in PMA-induced SVCT2 expression

Rubin and his colleagues [39] have previously shown that the human SVCT2 promoter activity is mediated by two variants (P1/exon 1a and P2/exon 1b variants) that encode the same SVCT2 protein. In order to determine the involvement of the two promoter variants in PMA-induced expression of SVCT2 in THP-1 monocytes, we measured changes in mRNA of these variants using transcript variant-specific primers. Whereas the basal abundance of the promoter variants was usually similar, both were augmented by 3 days of treatment with 100 nM PMA, although the relative increase was variable from experiment to experiment. These results are shown in the two panels of Fig. 10. In the left-hand panel of Fig. 10, it is shown that inhibitors of PKCβI/II (PKCβ Inhibitor, Gö 6983), B-Raf (SB-590885), MEK (PD 98059) and ERK (FR 180204) inhibited transcription of both the P1/exon 1a and the P2/exon 1b transcript variants. On the other hand, blockade of NF-κB activation by the NF-κB activation inhibitor completely abolished the transcription of PMA-induced P2/exon 1b mRNA, but had a little effect on the P1/exon 1a variant mRNA. Together, these results suggest that 1) both promoter variants are responsible for PMA-dependent SVCT2 activation, and 2) that failure of NF-κB blockade to completely decrease SVCT2 protein induction (Fig. 9) may be due to the involvement of other transcription factor (e.g. c-Fos/c-Jun) in the regulation of the P1/exon 1a transcript variant.

Fig. 10.

Analysis of SVCT2 transcript variants. (A) THP-1 monocytes were treated with PKC and MAPK pathway inhibitors followed by 100 nM PMA induction for 3 days and assay of SVCT2 transcript variants. (B) THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with the NF-κB Activation Inhibitor prior to 100 nM PMA for 3 days. Assay for SVCT2 transcript abundance was carried out by two-step RT-PCR with reverse transcription performed in the presence of exon 1a-specific (P1) or exon 1b-specifc (P2) forward primers and common reverse primer from exon 3.

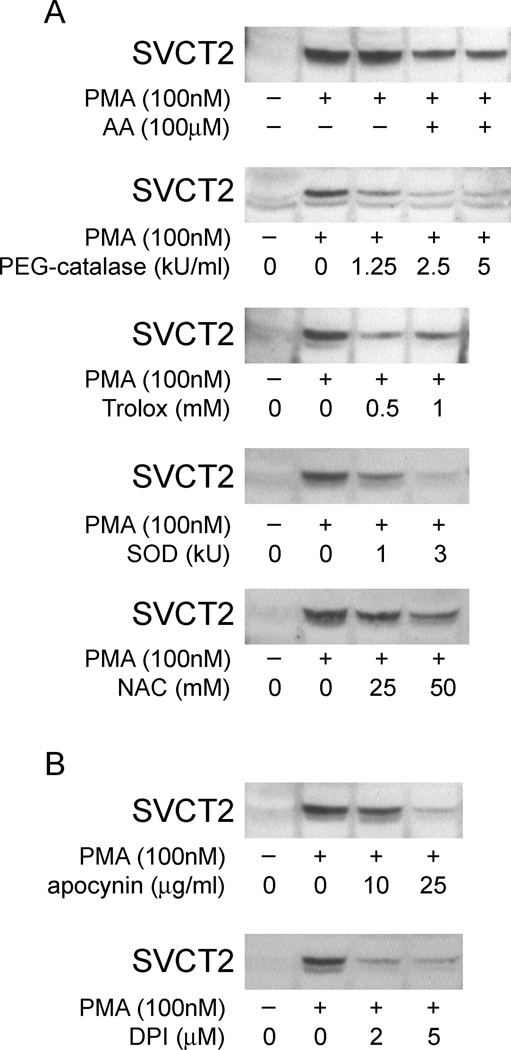

SVCT2 expression is suppressed by NADPH oxidase inhibitors

The induction of monocyte differentiation by PMA has been shown to activate PKC isozymes and thereby induce several signaling mediators, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) [40,41]. To determine whether PMA-stimulated ROS generation is involved in the inducible expression of SVCT2 in THP-1 cells, we assessed the effect of ROS on SVCT2 induction. As shown in Fig. 11A, the increase in SVCT2 induction was suppressed by pre-incubating cells with several antioxidants with distinctive modes of action, including AA, catalase, Trolox, (SOD), and NAC. Additionally, NADPH oxidase inhibitors, including apocynin and DPI, also significantly down-regulated the expression of SVCT2 by PMA (Fig. 11B). Taken together, these data support the notion that oxidative stress is involved in the regulation of SVCT2 expression.

Fig. 11.

SVCT2 expression is suppressed by antioxidants and by NADPH oxidase inhibitors. (A) ascorbate (AA), PEG-catalase, Trolox, SOD and NAC were added to the incubation medium 1 h before PMA (100 nM), after which culture was continued for an additional 3 days before harvesting the cells and SVCT2 immunoblotting. (B) NADPH oxidase inhibitors were added to THP-1 monocytes 1 h before PMA and SVCT2 protein was evaluated after 3 days in culture.

Discussion

Differentiation of monocytes into macrophages involves induction of numerous cellular processes that can support cell attachment, enhance motility induced by chemoattractants, release inflammatory proteins and enzymes, initiate phagocytosis, kill bacteria, and destroy foreign proteins. A role for ascorbate in the process of macrophage differentiation is plausible, based on its beneficial effects on differentiation and maturation in other cell types [5,42,43], as noted previously. We found that daily addition of ascorbate also facilitated THP-1 monocyte adhesion and morphologic differentiation induced over 3 days by low concentrations of PMA. This shows that ascorbate enhanced PMA-induced differentiation of monocytes, although it should be noted that ascorbate alone did not affect differentiation. As expected, THP-1 monocyte differentiation caused marked increases in the message for the monocyte-macrophage surface antigens CD11b and CD14. Although ascorbate did not affect CD11b message during PMA-induced differentiation, it decreased expression of CD14, which facilitates detection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Macrophages from the CD14 knockout mice show impaired activation of the NF-κB pathway and as a result LPS-induced IL-6 and TNF-α production is deficient [44]. Therefore, the effect of ascorbate to decrease CD14 expression in THP-1 macrophages could offer one mechanism to explain why ascorbate inhibits both NF-κB activation and suppresses release of downstream products of NF-κB activation, including IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-activated human monocytes [45]. These responses may be limited to the macrophage lineage, since ascorbate increases both CD11 and CD14 during promyelocytic HL-60 cell differentiation induced by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 [6].

PMA-induced differentiation of THP-1 monocytes caused a marked increase in expression and function of the specific ascorbate transporter SVCT2, as reflected by increases in SVCT2 mRNA, protein, and the transport Vmax without change in the Km. Identification of the SVCT2 as a ∼65 kDa protein on immunoblots was based on a predicted molecular weight of ∼70 kDa from the amino acid sequence of the human SVCT2 [46]. Although Savini, et. al. [20] have reported an apparent molecular weight of ∼50 kDa in human platelets, we and others [47] see higher molecular masses in human-derived cells. Previous studies suggest that induction of SVCT2 expression with cell differentiation may depend on cell type or the differentiation stimulus employed. For example, induction of differentiation in MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells by transforming growth factor-β was accompanied by increased specific ascorbate transport [42], which in this cell type would be on the SVCT2 [25]. On the other hand, C2C12 myoblasts induced to differentiate into myotubes by serum starvation showed decreased rates of ascorbate transport [48]. Our finding of strong SVCT2 induction due to PMA-induced differentiation of THP-1 monocytes suggests that a need for increased intracellular ascorbate accompanies the differentiation process. Indeed, when ascorbate was provided during differentiation, PMA-induced SVCT2 expression was decreased, indicating that intracellular ascorbate is involved in the regulation of differentiation. Intracellular ascorbate may also decrease function of its own transporter more rapidly within 1 hour [19,49], probably by inhibiting translocation of the SVCT2 to the plasma membrane from intracellular sites [19].

Phorbol esters such as PMA mimic diacylglycerol and induce cell differentiation through activation of the PKC pathway [32,50]. As expected, PMA induction of the SVCT2 required PKC activity. The PKC family comprises at least 11 closely related isoenzymes. Cells of monocyte/macrophage lineage express not only the classical (Ca2+-dependent) isoenzymes α, βI, and βII, but also the novel (Ca2+-independent) isoenzymes δ and ε, and the atypical isoenzyme ζ [33,51]. The present results show that PKCβ is required for PMA-stimulated induction of the SVCT2. Thus, PMA-stimulated SVCT2 expression was mimicked by bryostatin 2, a known competitive agonist of PKC with PMA. Second, use of a variety of PKC inhibitors with varying specificity showed that SVCT2 induction was mediated both by the PKCβI and the βII isoforms.

Movement of PKC to the plasma membrane is required for its ultimate activation [50]. This effect was observed in response to PMA stimulation for both PKCβII protein and for PKCβII that was phosphorylated on Thr641. Most PKC isoforms are activated in two steps. The first involves co-translational phosphorylation of Thr500 in the activation loop of PKCβII by the upstream kinase PDK-1 (Phosphoinositide-Dependent Kinase-1) or a related enzyme. Phosphorylation at the activation loop then triggers intracellular autophosphorylation at two C-terminal sites, the turn motif (Thr641 in PKCβII) and the hydrophobic motif (Ser660 in PKCβII) required for subsequent activation of PKC [52]. This results in a conformational change and facilitates cofactors such as diacylglycerol to remove an auto-inhibitory domain from the active site leading to the activation of PKC for downstream targets. Surprisingly, we found that PKCβII in THP-1 monocytes was constitutively phosphorylated on Thr641 and Ser660 and that Thr641-phosphorylated PKCβII was rapidly translocated to the plasma membrane during the first hour of PMA treatment. These results suggest that the main stimulus to PKCβII activation in THP-1 monocytes is translocation of its constitutively phosphorylated form and subsequent activation in the plasma membrane.

PKC-mediated activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway has been well-characterized, but the exact nature and order of events leading to Raf activation remain to be fully elucidated. PKC has been shown to activate Raf directly and induce cross-talk between PKC and Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways [53]. Alternatively, it has been proposed that PKC can activate Ras, which subsequently leads to Raf and ERK activation. Jurkat leukemic T cells [54], and primary rat ventricular myocytes [55] have exhibited Ras-dependent activation of MAPK by PMA; but in NIH3T3 cells [56], and HEK293 cells [57], this activation appears to be Ras-independent. Thus, the involvement of Ras in signaling processes initiated by PMA appears to be cell type-dependent. In the present study inhibitors of Ras farnesylation, the most critical step in post-translational processing requiring for Ras function, failed to suppress both SVCT2 induction and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, suggesting that PMA-mediated SVCT2 induction is Ras-independent.

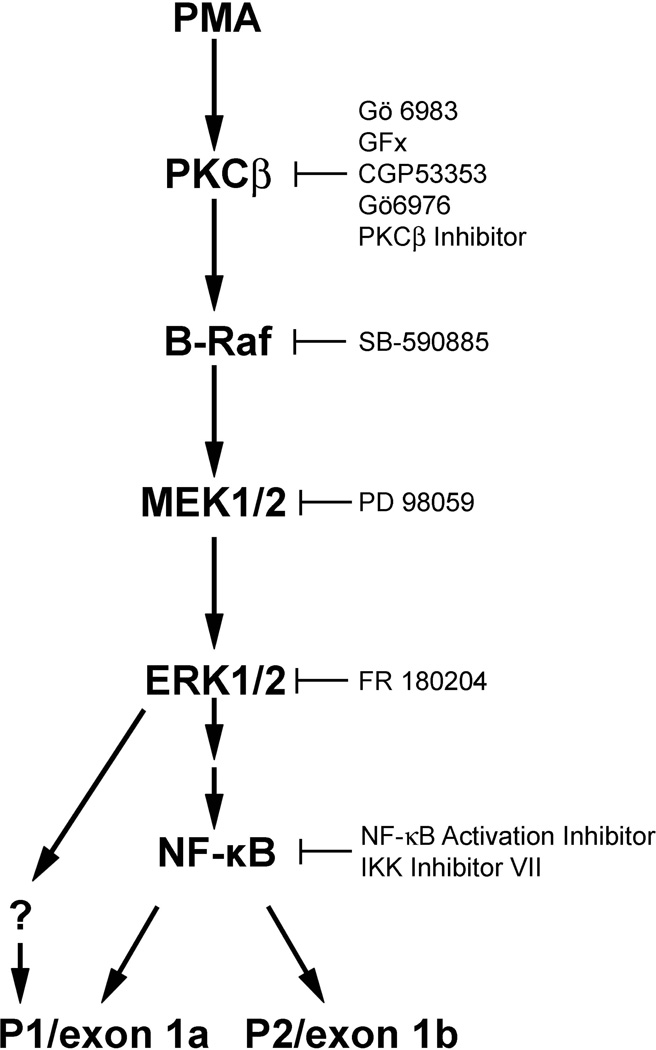

Activation of B-Raf and the other members of the Raf family is a complex process involving mechanisms that have not been completely elucidated. Several lines of evidence indicate that B-Raf and c-Raf may play different roles in cell differentiation and proliferation. c-Raf is thought to be responsible for the transient activation of the ERK pathway required for proliferation upon epidermal growth factor stimulation, while B-Raf causes a persistent activation of ERK required for differentiation in response to stimulation with nerve growth factor [58], consistent with our observations. In many cells, B-Raf is considered the major kinase involved in MEK phosphorylation [59,60]. Indeed, PMA treatment of THP-1 monocytes induced ERKI/II phosphorylation, which along with SVCT2 induction was prevented by a B-Raf inhibitor. On the other hand, inhibition of c-Raf by two different inhibitors did not affect ERK1/2 phosphorylation upon PMA treatment, suggesting that c-Raf may not be involved in PMA-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation and SVCT2 induction in THP-1 monocytes. In contrast to ERK1/2 phosphorylation, the increase of SVCT2 was not apparent until after 2 days of treatment with PMA (Fig. 1D). This is consistent with the notion that PMA induction of SVCT2 could be a consequence of the earlier ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The classical MAPK cascade (Scheme 1) consists of a three-kinase module that includes an MEK kinase (Raf kinases), which activates an MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK), which in turn activates a mitogen-responsive ERK1/2 corresponding to the classical MAPK. ERKs are serine-threonine kinases that when activated phosphorylate numerous substrates, including transcription factors. Although there may be multiple such transcription factors involved in ERK1/2-dependent SVCT2 activation, at least one of these appears to be NF-κB (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

A proposed signal transduction pathway that regulates PMA-stimulated SVCT2 expression during THP-1 monocyte differentiation.

The MAPK cascade is known to activate NF-κB via an indirect mechanism [61]. The transcription factor NF-κB in turn plays a key role in the activation of inflammatory response genes. In resting cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by association with an inhibitory protein IκB. In response to signaling by inflammatory cytokines, IκB kinase (IKK) is activated and phosphorylates IκB on two serine residues. IκB is then ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome, freeing NF-κB to migrate into the nucleus and activate gene expression. We found that IκB was degraded over several hours after treatment with PMA, showing that NF-κB is present in its active form early in the course of PMA treatment. Subsequent inhibition of NF-κB activation by two different inhibitors partially decreased SVCT2 protein expression during THP-1 monocyte differentiation. If NF-κB drives SVCT2 expression, the resulting increase in intracellular ascorbate could ameliorate the oxidant stress associated with NF-κB activation [62] and negatively feedback on NF-κB signaling [63].

The SVCT2 is unusual in that its expression is driven by two promoters that generate the same coding sequence [39]. In an effort to see whether PMA-stimulated SVCT2 expression might be regulated by one or the other promoter, selected inhibitors of each step in the activation cascade induced by PMA were tested for effects on promoter expression. Although generation of both promoter variants was inhibited by these agents, PMA-induced P2/exon 1b transcription was generally decreased more than that of P1/exon 1a. This was especially evident for inhibition of NF-κB activation. Although NF-κB activation appears important in SVCT2 induction, whether these pathways act in concert or separately remains to be determined.

Over the last several years, ROS have been implicated in the cell-signaling process. For example, many recent studies with various experimental systems indicate that MAPK species JNK and p38 are strongly activated by ROS or by a mild oxidative shift of the intracellular redox state. As to the relationship between ROS and ERK activation, while MAPK inhibitors completely prevented PMA-induced SVCT2 expression, indicating a critical role in the induction of SVCT2, several scavengers of different types of ROS (NAC, PEG-catalase, SOD, and Trolox) and NADPH oxidase inhibitors partially inhibited PMA-induced SVCT2 expression in THP-1 monocytes (Fig. 11), with no change of phosphorylated ERK (data not shown). This suggests the existence of a second mechanism of PMA-induced SVCT2 expression that is dependent on both ROS and ERK. In addition, H2O2 failed to up-regulate SVCT2 expression in the absence or presence of PMA (data not shown), suggesting that SVCT2 induction is probably tightly regulated by the differentiation of THP-1 monocytes. Further investigation of the relationship between ROS and PMA-induced SVCT2 will be needed.

In conclusion, these results suggest that increased ascorbate uptake mediated by the SVCT2 is a consequence of macrophage differentiation induced by PMA, that ascorbate itself modifies SVCT2 expression, and that several factors are involved in the transcriptional regulation of SVCT2 expression, including PKCβ1/II-dependent sustained activation of the MAPK pathway, ROS, and NF-κB pathway activation. Whether such findings relate to normal human monocyte differentiation remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

It was supported by NIH grant DK 50435 and by the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center (DK 20593). We appreciate GSK (United Kingdom) for B-Raf specific inhibitor SB-590885.

Abbreviations

- PKC

protein kinase C

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DHA

dehydroascorbic acid

- DPI

diphenylene iodonium

- SVCT2

Sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- NAC

N-acetyl cysteine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the 15th annual meeting of the Society for Free Radical Biology and Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, Nov. 2008.

References

- 1.Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. New vistas on macrophage differentiation and activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:14–16. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naito M. Macrophage differentiation and function in health and disease. Pathol. Int. 2008;58:143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu XM, Itoh N, Taniguchi T, Hirano J, Nakanishi T, Tanaka K. Stimulation of differentiation in sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 overexpressing MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;317:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SH, Lumelsky N, Studer L, Auerbach JM, McKay RD. Efficient generation of midbrain and hindbrain neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:675–679. doi: 10.1038/76536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eldridge CF, Bunge MB, Bunge RP, Wood PM. Differentiation of axon-related Schwann cells in vitro. I. Ascorbic acid regulates basal lamina assembly and myelin formation. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:1023–1034. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.2.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quesada JM, Lopez-Lluch G, Buron MI, Alcain FJ, Borrego F, Velde JP, Blanco I, Bouillon R, Navas P. Ascorbate increases the 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced monocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1996;59:277–282. doi: 10.1007/s002239900123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitsumoto Y, Liu Z, Klip A. A long-lasting vitamin C derivative, ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, increases myogenin gene expression and promotes differentiation in L6 muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;199:394–402. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganguly R, Durieux M-F, Waldman RH. Macrophage function in vitamin C-deficient guinea pigs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1976;29:762–765. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/29.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans RM, Currie L, Campbell A. The distribution of ascorbic acid between various cellular components of blood, in normal individuals, and its relation to the plasma concentration. Br. J. Nutr. 1982;47:473–482. doi: 10.1079/bjn19820059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergsten P, Amitai G, Kehrl J, Dhariwal KR, Klein HG, Levine M. Millimolar concentrations of ascorbic acid in purified human mononuclear leukocytes. Depletion and reaccumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:2584–2587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May JM, Li L, Qu ZC, Huang J. Ascorbate uptake and antioxidant function in peritoneal macrophages. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;440:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loke WM, Proudfoot JM, McKinley AJ, Croft KD. Augmentation of monocyte intracellular ascorbate in vitro protects cells from oxidative damage and inflammatory responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;345:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsukaguchi H, Tokui T, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Chen X-Z, Wang YX, Brubaker RF, Hediger MA. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature. 1999;399:70–75. doi: 10.1038/19986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastore P, Rizzetto T, Curcuruto O, Cin MD, Zaramella A, Marton D. Characterization of dehydroascorbic acid solutions by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:2051–2057. doi: 10.1002/rcm.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May JM, Qu ZC, Qiao H, Koury MJ. Maturational loss of the vitamin C transporter in erythrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;360:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May JM, Qu ZC, Whitesell RR, Cobb CE. Ascorbate recycling in human erythrocytes: Role of GSH in reducing dehydroascorbate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;20:543–551. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotiriou S, Gispert S, Cheng J, Wang YH, Chen A, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Miller GF, Kwon O, Levine M, Guttentag SH, Nussbaum RL. Ascorbic-acid transporter Slc23a1 is essential for vitamin C transport into the brain and for perinatal survival. Nature Med. 2002;8:514–517. doi: 10.1038/0502-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson JX. Ascorbic acid uptake by a high-affinity sodium-dependent mechanism in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1989;53:1064–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang WJ, Johnson D, Ma LS, Jarvis SM. Regulation of the human vitamin C transporters and expressed in COS-1 cells by protein kinase C. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1696–C1704. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00461.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savini I, Catani MV, Arnone R, Rossi A, Frega G, Del Principe D, Avigliano L. Translational control of the ascorbic acid transporter SVCT2 in human platelets. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:608–616. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujita I, Hirano J, Itoh N, Nakanishi T, Tanaka K. Dexamethasone induces sodium-dependant vitamin C transporter in a mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1. Br. J Nutr. 2001;86:145–149. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biondi C, Pavan B, Dalpiaz A, Medici S, Lunghi L, Vesce F. Expression and characterization of vitamin C transporter in the human trophoblast cell line HTR-8/SVneo: effect of steroids, flavonoids and NSAIDs. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2007;13:77–83. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savini I, Rossi A, Catani MV, Ceci R, Avigliano L. Redox regulation of vitamin C transporter SVCT2 in C2C12 myotubes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;361:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu XM, Itoh N, Taniguchi T, Nakanishi T, Tatsu Y, Yumoto N, Tanaka K. Zinc-induced sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 expression: potent roles in osteoblast differentiation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;420:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X, Itoh N, Taniguchi T, Nakanishi T, Tanaka K. Requirement of calcium and phosphate ions in expression of sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 and osteopontin in MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1641:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) Int. J. Cancer. 1980;26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwende H, Fitzke E, Ambs P, Dieter P. Differences in the state of differentiation of THP-1 cells induced by phorbol ester and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;59:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klezovitch O, Edelstein C, Scanu AM. Stimulation of interleukin-8 production in human THP-1 macrophages by apolipoprotein(a). Evidence for a critical involvement of elements in its C-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46864–46869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oda T, Hirota K, Nishi K, Takabuchi S, Oda S, Yamada H, Arai T, Fukuda K, Kita T, Adachi T, Semenza GL, Nohara R. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 during macrophage differentiation. Am. J. Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C104–C113. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00614.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaken S. Protein kinase C isozymes and substrates. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996;8:168–173. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parekh DB, Ziegler W, Parker PJ. Multiple pathways control protein kinase C phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2000;19:496–503. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HW, Ahn DH, Crawley SC, Li JD, Gum JR, Jr, Basbaum CB, Fan NQ, Szymkowski DE, Han SY, Lee BH, Sleisenger MH, Kim YS. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate up-regulates the transcription of MUC2 intestinal mucin via Ras, ERK, and NF-kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32624–32631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siow YL, Au-Yeung KK, Woo CW. O K Homocysteine stimulates phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase p47phox and p67phox subunits in monocytes via protein kinase Cbeta activation. Biochem. J. 2006;398:73–82. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitatani K, Idkowiak-Baldys J, Hannun YA. Mechanism of inhibition of sequestration of protein kinase C alpha/betaII by ceramide. Roles of ceramide-activated protein phosphatases and phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of protein kinase C alpha/betaII on threonine 638/641. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:20647–20656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouroedov A, Eto M, Joch H, Volpe M, Luscher TF, Cosentino F. Selective inhibition of protein kinase Cbeta2 prevents acute effects of high glucose on vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in human endothelial cells. Circulation. 2004;110:91–96. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133384.38551.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohori M, Kinoshita T, Okubo M, Sato K, Yamazaki A, Arakawa H, Nishimura S, Inamura N, Nakajima H, Neya M, Miyake H, Fujii T. Identification of a selective ERK inhibitor and structural determination of the inhibitor-ERK2 complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;336:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang B, Xu S, Brecher P, Cohen RA. Growth factors enhance interleukin-1 beta-induced persistent activation of nuclear factor-kappa B in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22:1811–1816. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000037679.60584.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurland JF, Voehringer DW, Meyn RE. The MEK/ERK pathway acts upstream of NF kappa B1 (p50) homodimer activity and Bcl-2 expression in a murine B-cell lymphoma cell line. MEK inhibition restores radiation-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32465–32470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin SA, Dey S, Reidling JC. Functional analysis of two regulatory regions of the human Na+ -dependent vitamin C transporter 2, SLC23A2, in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1732:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hmama Z, Knutson KL, Herrera-Velit P, Nandan D, Reiner NE. Monocyte adherence induced by lipopolysaccharide involves CD14, LFA-1, and cytohesin-1. Regulation by Rho and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1050–1057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traore K, Trush MA, George M, Jr, Spannhake EW, Anderson W, Asseffa A. Signal transduction of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-induced growth inhibition of human monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells is reactive oxygen dependent. Leuk. Res. 2005;29:863–879. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson JX, Dixon SJ. Ascorbate concentration in osteoblastic cells is elevated by transforming growth factor-β. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;268:E565–E571. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.4.E565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu S, Li L, Weeber EJ, May JM. Ascorbate transport by primary cultured neurons and its role in neuronal function and protection against excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:1046–1056. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore KJ, Andersson LP, Ingalls RR, Monks BG, Li R, Arnaout MA, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. Divergent response to LPS and bacteria in CD14-deficient murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 2000;165:4272–4280. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hartel C, Strunk T, Bucsky P, Schultz C. Effects of vitamin C on intracytoplasmic cytokine production in human whole blood monocytes and lymphocytes. Cytokine. 2004;27:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daruwala R, Song J, Koh WS, Rumsey SC, Levine M. Cloning and functional characterization of the human sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters hSVCT1 and hSVCT2. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu X, Iguchi T, Itoh N, Okamoto K, Takagi T, Tanaka K, Nakanishi T. Ascorbic acid transported by sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 stimulates steroidogenesis in human choriocarcinoma cells. Endocrinology. 2007;149:73–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savini I, Catani MV, Duranti G, Ceci R, Sabatini S, Avigliano L. Vitamin C homeostasis in skeletal muscle cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;38:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson JX, Jaworski EM, Kulaga A, Dixon SJ. Substrate regulation of ascorbate transport activity in astrocytes. Neurochem. Res. 1990;15:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/BF00965751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan SL, Parker PJ. Emerging and diverse roles of protein kinase C in immune cell signalling. Biochem. J. 2003;376:545–552. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keranen LM, Dutil EM, Newton AC. Protein kinase C is regulated in vivo by three functionally distinct phosphorylations. Curr. Biol. 1995;5:1394–1403. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolch W, Heidecker G, Kochs G, Hummel R, Vahidi H, Mischak H, Finkenzeller G, Marme D, Rapp UR. Protein kinase C alpha activates RAF-1 by direct phosphorylation. Nature. 1993;364:249–252. doi: 10.1038/364249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li YQ, Hii CS, Costabile M, Goh D, Der CJ, Ferrante A. Regulation of lymphotoxin production by the p21ras-raf-MEK-ERK cascade in PHA/PMA-stimulated Jurkat cells. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3316–3320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiloeches A, Paterson HF, Marais R, Clerk A, Marshall CJ, Sugden PH. Regulation of Ras.GTP loading and Ras-Raf association in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes by G protein-coupled receptor agonists and phorbol ester. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade by phorbol ester is mediated by Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19762–19770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Vries-Smits AM, Burgering BM, Leevers SJ, Marshall CJ, Bos JL. Involvement of p21ras in activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2. Nature. 1992;357:602–604. doi: 10.1038/357602a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ming XF, Burgering BM, Wennstrom S, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin CH, Bos JL, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Activation of p70/p85 S6 kinase by a pathway independent of p21ras. Nature. 1994;371:426–429. doi: 10.1038/371426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vaudry D, Stork PJ, Lazarovici P, Eiden LE. Signaling pathways for PC12 cell differentiation: making the right connections. Science. 2002;296:1648–1649. doi: 10.1126/science.1071552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mikula M, Schreiber M, Husak Z, Kucerova L, Ruth J, Wieser R, Zatloukal K, Beug H, Wagner EF, Baccarini M. Embryonic lethality and fetal liver apoptosis in mice lacking the c-raf-1 gene. EMBO J. 2001;20:1952–1962. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huser M, Luckett J, Chiloeches A, Mercer K, Iwobi M, Giblett S, Sun XM, Brown J, Marais R, Pritchard C. MEK kinase activity is not necessary for Raf-1 function. EMBO J. 2001;20:1940–1951. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakano H, Shindo M, Sakon S, Nishinaka S, Mihara M, Yagita H, Okumura K. Differential regulation of IkappaB kinase alpha and beta by two upstream kinases, NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3537–3542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allen RG, Tresini M. Oxidative stress and gene regulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:463–499. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cárcamo JM, Pedraza A, Bórquez-Ojeda O, Golde DW. Vitamin C suppresses TNFα-induced NFkappaB activation by inhibiting IkappaBα phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12995–13002. doi: 10.1021/bi0263210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]