Abstract

Introduction and methods

We analyzed DNA samples isolated from individuals born with cleft lip and cleft palate to identify deletions and duplications of candidate gene loci using array comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH).

Results

Of 83 syndromic cases analyzed we identified one subject with a previously unknown 2.7 Mb deletion at 22q11.21 coinciding with the DiGeorge syndrome region. Eighteen of the syndromic cases had clinical features of Van der Woude syndrome and deletions were identified in 5 of these, all of which encompassed the interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene. In a series of 104 nonsyndromic cases we found one subject with a 3.2 Mb deletion at chromosome 6q25.1-25.2 and another with a 2.2 Mb deletion at 10q26.11-26.13. Analyses of parental DNA demonstrated that the two deletion cases at 22q11.21 and 6q25.1-25.2 were de novo, while the deletion of 10q26.11-26.13 was inherited from the mother, who also has cleft lip. These deletions appear likely to be causally associated with the phenotypes of the subjects. Estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) genes from the 6q25.1-25.2 and 10q26.11-26.13, respectively, were identified as likely causative genes using a gene prioritization software.

Discussion

We have shown that array-CGH analysis of DNA samples derived from cleft lip and palate subjects is an efficient and productive method for identifying candidate chromosomal loci and genes, complementing traditional genetic mapping strategies.

Keywords: cleft lip, cleft palate, array-CGH, candidate gene

INTRODUCTION

Orofacial clefts, are a common birth defect, affecting approximately 1–2 per 1,000 births [1]. Both genetic and environmental factors are known to contribute to the occurrence of cleft lip and palate, making it complicated to elucidate causative mechanisms. Cleft lip and palate may be subdivided into two phenotypic groups: cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P), and cleft palate (CP) alone [2]. In addition approximately 30% of CL/P and 50% of CP cases are recognized as components of syndromes that show additional characteristic features [3]. A modeling study suggests that as many as 14 loci may be involved in the etiology of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts [4]. Considerable efforts have been made seeking candidate gene(s) for nonsyndromic clefts through linkage analysis, association studies and candidate gene sequencing [5–8], but some contributing genes remain to be identified.

The human genome project has produced a range of tools and resources that can be used for comprehensive gene searches. Human bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries were used as one fundamental resource for mapping and sequencing the human genome [9–12]. The mapped and sequenced BAC clones have subsequently become powerful resources as diagnostic tools to identify chromosomal abnormalities using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and array comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH) [12]. Array-CGH has been developed as a method to identify and map sub-microscopic deletions/duplications simultaneously onto the genome sequence [13]. Identification of microdeletions using array-CGH has proven to be very powerful strategy to narrow down candidate disease gene regions for subsequent gene hunting. For instance, overlapping deletions of chromosome 8q12 were identified from CHARGE association subjects using array-CGH, and subsequently, a causative gene (CHD7) was identified from the candidate region [14]. Furthermore, sub-microscopic chromosomal imbalances that are considered to be clinically relevant have been identified using array-CGH with children who have mental retardation and multiple congenital anomalies [15, 16]. In addition, it has become feasible to predict likely causative genes among a number of genes in a deleted segment by assessing the biological roles of each gene from publicly available data sets [17]. Here we report screening candidate genes which are likely involved in the etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate by analyses of DNA samples isolated from syndromic and nonsyndromic cleft subjects using array-CGH.

METHODS

DNA sequence

We used hg17, Human May 2004 Assembly, for all analyses.

Reference DNA

Reference DNA was isolated from blood obtained from an anonymous healthy male donor and used for all the hybridizations.

Study population

We selected three study populations for this project (Table 1). In this study, we defined as familial cases if one or more first degree relatives (parents or siblings) have the same phenotypes. First, we chose 20 children (Table 1A) with clinical features of Van der Woude syndrome (VWS) or with lower lip pits, and who had no mutations when all interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) exons were sequenced. The clinical diagnosis of VWS was based on published criteria that include one or more of the following cleft lip, cleft palate, hypodontia and at least one affected member of the family with lower lip pits [18].

Table 1.

Study populations

| A: Van der Woude syndrome or lower lip pits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample origin | Phenotype | Family history | |||

| Canada, France, Germany, Philippines, Switzerland, UK, USA | 20 | VWS | 18 | Positive | 16 |

| Negative | 2 | ||||

| lower lip pits | 2 | Positive | 0 | ||

| Negative | 2 | ||||

| B: Syndromic cases: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample origin | Phenotype | Family history | |||

| Iowa | 22 | Cleft lip ± cleft palate | 13 | Positive | 1 |

| Negative | 12 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||

| Cleft palate only | 9 | Positive | 2 | ||

| Negative | 7 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||

| Philippines | 41 | Cleft lip ± cleft palate | 34 | Positive | 2 |

| Negative | 31 | ||||

| Unknown | 1 | ||||

| Cleft palate only | 7 | Positive | 0 | ||

| Negative | 7 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||

| C: Nonsyndromic cases: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample origin | Phenotype | Family history | |||

| Iowa | 54 | Cleft lip ± cleft palate | 41 | Positive | 5 |

| Negative | 36 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||

| Cleft palate only | 13 | Positive | 2 | ||

| Negative | 8 | ||||

| Unknown | 3 | ||||

| Philippines | 48 | Cleft lip ± cleft palate | 43 | Positive | 9 |

| Negative | 33 | ||||

| Unknown | 1 | ||||

| Cleft palate only | 5 | Positive | 1 | ||

| Negative | 4 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||

| Other area | 2 | Cleft lip ± cleft palate | 2 | Positive | 0 |

| Negative | 1 | ||||

| Unknown | 1 | ||||

Columns “Sample origin” indicate where the DNA samples were obtained.

Second, we selected 85 phenotypically heterogeneous children with syndromic clefts: they had other non-cleft major malformations, mental retardation, or microcephaly and included some infants with recognized patterns of malformations, for example, possible Aarskog syndrome, hemifacial microsomia, or amniotic bands. Of 85 DNA samples, 63 samples passed our quality standard and were subjected to the analysis with array-CGH (Table 1B).

Third, we selected 104 nonsyndromic cleft lip and cleft palate subjects, and each was analyzed by array-CGH (Table 1C).

Karyotypes were not obtained on any samples from the Philippines. For samples from Iowa the nonsyndromic cases were not karyotyped while the syndromic cases did have karyotypes done by standard cytogenetics (ones with identified abnormalities were excluded from this analysis). For cases from the Philippines clinical information was very limited and obtained in a brief (less than five minute) interview and physical examination. For samples from Iowa subjects were clinically examined, and medical, family and pregnancy histories were obtained in a routine manner [19]. DNA from the parents of subjects with apparent cytogenetic abnormalities were analyzed with array-CGH to confirm the identified deletions/duplications as either de novo or inherited. All samples came from cases collected with IRB approvals (199804080, 199804081, 200109094 and 200003065) and came from both US and overseas populations.

Array-CGH

We generated array-CGH slides containing >32,000 BAC clones covering >99% of the human genome sequence [15, 20]. The size for detecting copy number changes can be theoretically as small as 80 kb using the clone set [20]. Test and reference DNA was labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 and hybridized to the slides. Images were captured and processed after washing. Normalized hybridization results were displayed graphically by plotting chromosome positions (X axis) against log2 (Test/Reference) values (Y axis) (Supplemental Methods). Deletion/duplication loci were first automatically scored using CGHplotter and GLAD, and then manually inspected. To reduce the noise, we focused on the loci at which three or more overlapping clones concurrently showed deletion/duplication signals for the analyses of DNA samples from syndromic and nonsyndromic subjects. The practical size of detecting copy number changes therefore is approximately 300 kb on average.

Polymorphic copy number variation

Significant numbers of copy number variation (CNV) sites have been identified and deposited in publicly available databases [http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/, http://humanparalogy.gs.washington.edu/structuralvariation/; [21–28]]. The locus of each copy number variation site in the databases was converted into the mapping position of BAC clones in the 32k set and used as guide to evaluate whether duplications/deletions are pathogenic or presumably non-pathogenic polymorphic changes. It was, however, not possible to completely overlay the known CNVs to our clone set, because the size and position of many known CNVs were reported using BAC clones that originated from different BAC clone sets [23, 25, 27]. Reproducible deletion/duplication loci, which often overlap with known polymorphic CNVs, were considered to be likely non-pathogenic CNVs.

Quantitative PCR

A set of quantitative PCR (qPCR) probes was used to verify the deletion of chromosome 22q11.21 as described [29].

Gene prioritization

We attempted to specify candidate genes using gene prioritization software, “Endeavour” [17] (Supplemental Methods). Among known candidate genes we used the following genes as a training (reference) set: IRF6, MSX1, PVRL1, TBX22, SUMO1, TGFA, TP63, EDN1, FGFR1, PPP3CC, FOXE1, TGFB3, GABRB3, FOXC2, RARA, BCL3, BMP4 [6, 19, 30].

RESULTS

Van der Woude syndrome and/or cases with lip pits

As a pilot study we analyzed 20 DNA samples from children with VWS or lower lip pits by array CGH. Most of these infants with VWS came from families with affected relatives (Table 1A). We identified 5 subjects who had deletions at chromosome band 1q32.2 where the IRF6 gene resides (not shown). Two of these five subjects were known previously to have IRF6 deletions [31, 32], but were blindly included to assess the feasibility of detecting microdeletions. The size of these five microdeletions ranged from 100 kb to 1 Mb. All five cases had positive VWS family histories. We also found a 9.1 Mb duplication of chromosome 8p21.3-8p12 and a 11.6 Mb deletion of chromosome 8q23.1-8q24.12 (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 1A) from a subject who has lower lip pits, multiple congenital anomalies including oligodactyly with absence of a left toe, and abnormal neurodevelopment, but no cleft. The proband DNA was analyzed because lower lip pits are one of the typical phenotypic features of VWS. Analysis of maternal DNA showed no chromosome 8 abnormality, but no paternal DNA was available; thus we could not determine whether the deletion and duplication were inherited from the father or de novo, but it is likely de novo given the severe phenotype in the child.

Table 2.

| Sample ID | Cytogenetic band | hg17 position | Del/Dup | Size (Mb) | Inherited or de novo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syndromic | A | 8p21.3-p12 | chr8:23270459–32377014 | Dup | 9.1 | Not determined |

| 8q23.1-q24.12 | chr8:110057120–121636326 | Del | 11.6 | Not determined | ||

| B | 22q11.21 | chr22:17308437–20001403 | Del | 2.7 | de novo | |

| Non-syndromic | C | 6q25.1-q25.2 | chr6:152077664–155256384 | Del | 3.2 | de novo |

| D | chr10q26.11-q26.13 | chr10:121490548–123727263 | Del | 2.2 | Inherited from mother |

“Del” and “Dup” stand for deletion and duplication, respectively. The “hg17 position” column indicates where each deletion and duplication is approximately localized at UCSC Genome Browser on Human May 2004 Assembly. The breakpoint boundaries for the subjects A, B and D are determined using the most proximal and distal ends of BACs which indicate deletion/duplication. The deletion boundaries for the subject C is determined using the most distal and proximal SNP markers (rs851997 and rs1106753) which indicate Mendelian incompatibilities.

Syndromic cases

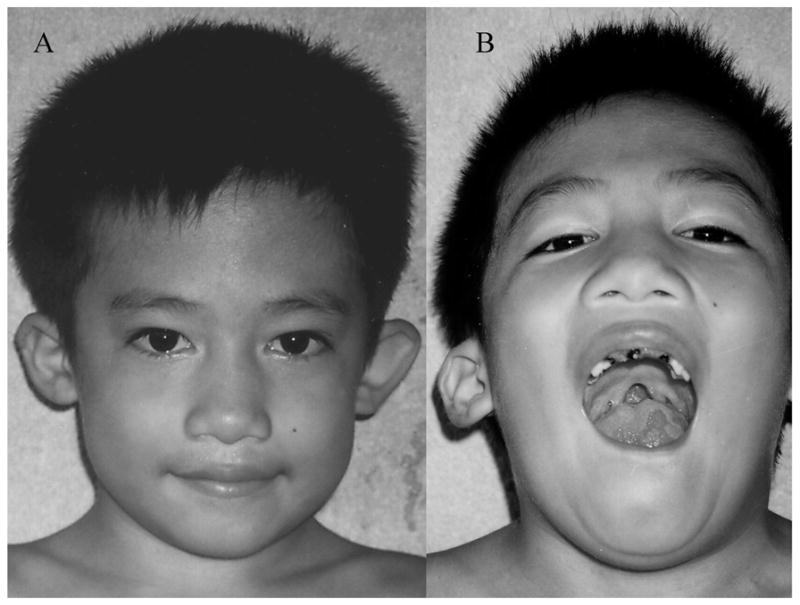

We analyzed 63 subjects with syndromic cleft lip or cleft palate by array-CGH (Table 1B). We found a 2.7 Mb deletion at chromosome 22q11.21 (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 1B) from a subject with cup shaped ears, a cleft palate and a thumb anomaly (Figure 1). This case came from samples collected in the Philippines and had not had a previous chromosome or microdeletion analysis performed. No cells were available for chromosome 22 FISH analysis. The deleted region coincides with the known velocardiofacial (DiGeorge) syndrome region [33]. This Philippine subject was not clinically diagnosed with velocardiofacial (DiGeorge) syndrome, when the DNA sample was archived. Analysis of parental DNA samples proved that the deletion was de novo. The copy numbers for the exon 12 of the UFD1L gene in the region were determined using qPCR to be 1, 2 and 2 from the subject, paternal and maternal DNA samples, respectively, confirming the de novo deletion of the proband’s DNA.

Figure 1.

A: Child with a 2.7 Mb deletion of chromosome 22q11.21 shows cup shaped ears. B: Other features of chromosome 22q11.21 deletion are apparent: cleft palate and tubular nose.

Nonsyndromic cases

We analyzed 104 DNA samples from nonsyndromic cleft lip or cleft palate subjects by array-CGH (Table 1C). First, we found a 3.2 Mb deletion at chromosome 6q25.1-25.2 from a subject with cleft lip (unilateral right) and cleft palate (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 1C). Analysis of parental DNA with array-CGH revealed that the deletion is de novo. We genotyped 57 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), with average spacing at 56 kb within the 3.2 Mb region from the subject and parents (Table 3 and Supplemental Methods). For the proband, the genotypes of markers rs17855719 and rs2273898 were determined to be heterozygous; these were, therefore, the closest informative markers from the proximal and distal breakpoints, respectively. No Mendelian incompatibility for the twelve markers distal to rs2273898 was detected, confirming diploidy of the region (not shown). For the proband, the remaining forty-three markers between rs17855719 and rs2273898 were each genotyped as homozygous. Apparent Mendelian inconsistencies were identified at 11 of the 43 SNPs by comparing genotypes of the proband – parents trio, indicating that 11 hemizygous genotypes were incorrectly typed as homozygous due to the deletion. Twenty-nine of the remaining 32 homozygous genotypes were also considered to be hemizygous, because these were located between the incompatible markers (rs851997 – rs1106753). It was not possible to conclude whether the remaining three distal markers, rs911192, rs6924188 and rs7752042 were hemizygous or homozygous. The proximal breakpoint of the deletion was narrowed down to a 43 kb region between markers rs17855719 and rs851997 and the distal breakpoint was localized to a 120 kb region between rs1106753 and rs2273898. It was also apparent that the microdeletion arose on the paternal chromosome 6. The size and location (3.18 Mb, chr6:152077664–155256384) of the deleted region estimated from the genotyping results were fairly consistent with the region obtained from the array-CGH (3.13 Mb, ch6: 151990265–155117950).

Table 3.

| hg17 | 152,031,295 | 152,077,664 | 152,100,894 | 155,220,077 | 155,256,384 | 155,256,416 | 155,300,248 | 155,343,594 | 155,376,430 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP ID | rs17855719 | rs851997 | rs3020331 | rs3800002 | rs1106753 | rs911192 | rs6924188 | rs7752042 | rs2273898 |

| Proband | GA | GG | CC | AA | GG | GG | CC | TT | GC |

| Father | AA | AA | CC | GG | AA | GG | CC | TC | GC |

| Mother | GG | CT | AA | GG | GA | CT | TT | GC |

Nine of 57 SNP genotype results at chromosome 6q25.1-q25.2 are shown. Three SNP genotypes near proximal breakpoint and six near distal breakpoint are summarized in the Table.

A second microdeletion, 2.2Mb in length, was located at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 from a subject with cleft lip without cleft palate (CL/P) (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 1D). The mother of the subject also has cleft lip without cleft palate (Supplemental Figure 2). The identical 2.2 Mb deletion was identified from maternal DNA (not shown) whereas no paternal deletion was found. No DNA samples were available from the other family members. We noted that the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene was located within the deleted 2.2 Mb region (Supplemental Figure 3A). We genotyped 4 markers near FGFR2 gene, but no informative markers were identified. We sequenced all exons of FGFR2 from the subject and parents and found no mutation. We however found a Mendelian inconsistency in marker rs4647915 which is 43 bp upstream of the start of exon 14 of FGFR2. The mother and father had homozygous (CGGTGTTTT) and heterozygous (CGGTGTTTT/CGGT_TTTT) genotypes, respectively, whereas the proband had a homozygous (CGGT_TTTT) genotype, consistent with hemizygosity and indicating paternal but no maternal inheritance. Neither the mother nor the child had any other features to support syndromic consideration and both are of normal intelligence.

Gene prioritization

We found 11 (ESR1, SYNE1, MYCT1, VIP, FBXO5, MTRF1L, RGS17, OPRM1, PIP3-E, CNKSR3, RBM16) and 9 (INPP5F, C10orf119, SEC23IP, PPAPDC1A, C10orf85, BRWD2, FGFR2, ATE1, C10orf86) genes within the two clefting candidate loci at 6q25.1-25.2 and 10q26.11-26.13 (Supplemental Figure 3). We prioritized the genes whose haploinsufficiency may have caused cleft lip with the aid of the bioinformatics tool, Endeavour gene prioritization program [17]. The prioritization is determined based on the hypothesis that the novel candidate genes play a similar role or share biological processes with the genes known to be associated with cleft lip or cleft palate. We listed 17 known clefting genes as a reference set (Methods). The available information of the 11 and 9 genes within the two microdeletions was then compared with these of the reference set (Supplemental Methods). Estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) genes were listed as the highest priority genes at 6q25.1-25.2 and 10q26.11-26.13 loci, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of these investigations was to assess the utility of array-CGH for identifying candidate chromosomal loci and genes associated with cleft lip or cleft palate. We theorized that finding such deletions/duplications would provide significant evidence for further defining candidate genes or regulatory elements, even from a single case. Array-CGH offers the opportunity to identify candidate genes for which haploinsufficiency is one mechanism. A genome-wide array-CGH assay has been proven to be an efficient method to identify sub-microscopic DNA copy number changes causing various disorders [15, 16]. For our investigations, we chose to analyze DNA samples from 100 syndromic and 100 nonsyndromic cleft lip and cleft palate subjects to detect events with frequencies on the order of 1%.

First, we analyzed 20 subjects with VWS or lower lip pits, because previous investigations suggested that haploinsufficiency of IRF6 causes VWS [31, 32, 34]. We identified 5 microdeletions at chromosome 1q32.2, a region that includes the IRF6 gene. Our results, thus, provide further evidence for a haploinsufficiency mechanism of IRF6 as a cause of VWS. We also identified a 9.1 Mb duplication at chromosome 8p21.3-8p12 and a 11.6 Mb deletion at 8q23.1-8q24.12 from a subject who has lower lip pits, multiple congenital anomalies and abnormal neurodevelopment. Although this subject did not have cleft lip or cleft palate, it is of importance to note that we found a second candidate locus for lower lip pits, in addition to IRF6. The results from these subjects showed the value and practicality of identifying deletions/duplications from the DNA samples used in this study. These encouraging results allowed us to then use array-CGH to identify potential candidate genes among infants with syndromic and nonsyndromic clefts.

We hypothesized that contiguous gene syndromes might underlie some syndromic cases of cleft lip and palate caused by deletions/duplications spanning neighboring genes that created a more complex phenotype than an isolated cleft. This strategy assumed that there was a better likelihood of identifying deletions/duplications from syndromic cases than from nonsyndromic cases. However, from the analyses of 63 syndromic subjects, we found only one infant with a 2.7 Mb deletion of chromosome 22q11.21 from a cleft palate subject with findings (cup shaped ears and tubular nose) consistent with the phenotype of velocardiofacial (DiGeorge) syndrome [33].

Third, from array-CGH analyses of 104 nonsyndromic cleft lip or cleft palate subjects, we identified two novel microdeletions, a 2.2 Mb deletion at chromosome 10q26.11-q26.13 and a 3.2 Mb deletion at 6q25.1-25.2. We found that the deletion at 10q26.11-q26.13 was inherited from her mother, who also has isolated CL/P. The FGFR2 was ranked as the highest priority gene in this region using Endeavour gene prioritization program. It has been reported that 51 of 51 homozygous Fgfr2b−/− knockout mouse embryos exhibited a cleft palate [35]. Palatal formation was affected at an early stage of development (day E13) and the palatal processes failed to grow, with a thin palatal epithelium. This suggested an important role for Fgfr2 in “budding” of the palatal processes and in maintaining growth. More recently, several missense mutations of FGFR2 were identified from nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate subjects [7]. A R84S codon change was found in one subject with bilateral cleft lip and palate, while a D138N codon mutation was found in five Filipino study subjects with cleft lip. R84S is located within the Ig domain (D1) of FGFR2, while D138N is located in the D1–D2 linker/acid box domain. Both amino acids are conserved among several vertebrates and other FGFRs. Further investigation will be required to determine if these missense mutations create a functional haploinsufficiency state. Nevertheless, our observation of a familial microdeletion of FGFR2 associated with isolated cleft lip strongly suggests that haploinsufficiency of FGFR2 is at least one pathogenetic mechanism through which mutation of FGFR2 causes clefting. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a deletion of FGFR2 from a cleft lip subject.

We did not find a known clefting candidate gene within the 3.2 Mb deletion of chromosome 6q25.1-25.2. However it is highly likely that the deletion was causally related, because it is de novo. Chromosome 6q23-25 has been reported as a clefting candidate locus based on a 10-cM genome-wide linkage scan, but no candidate gene has been identified [5]. We estimated the approximate chromosomal locus to be chr6:113633000–131897000 using the reported genetic position (120–130 cM) on the May 2004 genome sequence assembly. It appears that the locus is approximately 20 Mb proximal to the 3.2 Mb chromosome 6q25.1-q25.2 region. We identified ESR1 as the highest priority candidate gene within the region using Endeavour. It has been reported that expression of estrogen receptor alpha occures during the differentiation of tooth-forming cells [36]. Previous studies have shown that the estrogen receptor acts as a transcriptional corepressor for Smad3 (Sma and MAD-related protein 3), which is one of the major intracellular transducers of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling [37, 38]. All isoforms (1, 2 and 3) of the TGF-β family play an important role in palate development via interaction with Smad signaling system [37]. Further investigation is required to support our finding that haploinsufficiency of ESR1 is a cause of cleft lip.

In summary, we have shown that identifying deletions/duplications using array-CGH is an efficient and productive strategy to pinpoint candidate gene loci associated with cleft lip and cleft palate, complementing other genetic approaches. The availability of higher resolution arrays will permit identification of even smaller deletions and will make an additional contribution to the comprehensive approaches that are needed to identify the genes involved in complex traits involving birth defects. In addition, based on these initial results, microdeletions now become an important consideration in the genetic counseling of families who have had a child with van der Woude syndrome or with an isolated cleft.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Representative diagrams of human chromosome 8 (A), 22 (B), 6 (C) and 10 (D) are illustrated at the bottom of each figure with cytogenetic bands and positions. The numbers at the top of each figure indicate DNA sequence position from hg17, May 2004 Assembly. Array-CGH results are displayed by plotting position of each BAC on the DNA sequence (X axis) against log2 (Test/Reference) values (Y axis). (A) A 9.1 Mb duplication of chromosome 8p21.3-8p12 and a 11.6 Mb deletion of chromosome 8q23.1-8q24.12 were identified from a subject who has lower lip pits, multiple congenital anomalies including oligodactyly with absence of a left toe, and abnormal neurodevelopment. (B) A 2.7 Mb deletion at chromosome 22q11.21 was found from a subject with cup shaped ears, a cleft palate and a thumb anomaly. (C) A 3.2 Mb deletion was identified at chromosome 6q25.1-25.2 from a subject with cleft lip (unilateral right) with cleft palate. (D) A 2.2 Mb deletion was found at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 from a subject with cleft lip without palate. The deleted regions were highlighted with black stripe on each chromosome diagram.

Supplemental Figure 2: Pedigree of the subject D (Table 1) who has cleft lip

Square and circle symbols represent male and female individuals, respectively. Affected individuals are shown with blackened symbols, and unaffected individuals are shown with white symbols. The subject and her mother were affected individuals in this family.

Supplemental Figure 3: A 2.2 Mb region at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 (A) and a 3.2 Mb at chromosome 6q25.1-25.2 (B) on UCSC Genome Browser

The horizontal bold lines represent BAC clones spanning at each region. Genes assigned in the region was displayed using “RefSeq Genes track” with thin horizontal line with short vertical lines. FGFR2 and ESR1 are identified at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 and 6q25.1-25.2, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the families who agreed on participating in this study. The study was performed under the IRB approvals at the University of Iowa and Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (CHORI). The authors thank Joris Veltman, Erik Huys (University Medical Centre Nijmegen), Lucia Carbone, David Iovannisci, Barbara Swiatkiewicz, Chik On Choy, Mili Gera, Maria Leonor Kimwell, Alfred Tsang, Karen Catanese and Sharry Goree (CHORI) and Susie McConnell (University of Iowa) for their assistance. There are no competing interests. The work was funded by grants from the NICDR, R21-DE017005 to PDJ, R01-DE13513 to BCS, R37 DE-08559 and P50 DE-16215 to JCM.

References

- 1.Shaw GM, Croen LA, Curry CJ. Isolated oral cleft malformations: associations with maternal and infant characteristics in a California population. Teratology. 1991;43(3):225–8. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420430306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fogh-Anderson P. Genetic and non-genetic factors in the etiology of facial clefts. Scand J Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1967;1:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanier P, Moore GE. Genetics of cleft lip and palate: syndromic genes contribute to the incidence of non-syndromic clefts. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(Spec No 1):R73–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schliekelman P, Slatkin M. Multiplex relative risk and estimation of the number of loci underlying an inherited disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(6):1369–85. doi: 10.1086/344779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marazita ML, Murray JC, Lidral AC, Arcos-Burgos M, Cooper ME, Goldstein T, Maher BS, Daack-Hirsch S, Schultz R, Mansilla MA, et al. Meta-analysis of 13 genome scans reveals multiple cleft lip/palate genes with novel loci on 9q21 and 2q32-35. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(2):161–73. doi: 10.1086/422475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jugessur A, Murray JC. Orofacial clefting: recent insights into a complex trait. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15(3):270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley BM, Mansilla MA, Ma J, Daack-Hirsch S, Maher BS, Raffensperger LM, Russo ET, Vieira AR, Dode C, Mohammadi M, et al. Impaired FGF signaling contributes to cleft lip and palate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4512–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607956104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vieira AR, Avila JR, Daack-Hirsch S, Dragan E, Felix TM, Rahimov F, Harrington J, Schultz RR, Watanabe Y, Johnson M, et al. Medical sequencing of candidate genes for nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(6):e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osoegawa K, Mammoser AG, Wu C, Frengen E, Zeng C, Catanese JJ, de Jong PJ. A bacterial artificial chromosome library for sequencing the complete human genome. Genome Res. 2001;11(3):483–96. doi: 10.1101/gr.169601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson JD, Marra M, Hillier L, Waterston RH, Chinwalla A, Wallis J, Sekhon M, Wylie K, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, et al. A physical map of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):934–41. doi: 10.1038/35057157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung VG, Nowak N, Jang W, Kirsch IR, Zhao S, Chen XN, Furey TS, Kim UJ, Kuo WL, Olivier M, et al. Integration of cytogenetic landmarks into the draft sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):953–8. doi: 10.1038/35057192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinkel D, Segraves R, Sudar D, Clark S, Poole I, Kowbel D, Collins C, Kuo WL, Chen C, Zhai Y, et al. High resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat Genet. 1998;20(2):207–11. doi: 10.1038/2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vissers LE, van Ravenswaaij CM, Admiraal R, Hurst JA, de Vries BB, Janssen IM, van der Vliet WA, Huys EH, de Jong PJ, Hamel BC, et al. Mutations in a new member of the chromodomain gene family cause CHARGE syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(9):955–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries BB, Pfundt R, Leisink M, Koolen DA, Vissers LE, Janssen IM, Reijmersdal S, Nillesen WM, Huys EH, Leeuw N, et al. Diagnostic genome profiling in mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(4):606–16. doi: 10.1086/491719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thienpont B, Mertens L, de Ravel T, Eyskens B, Boshoff D, Maas N, Fryns JP, Gewillig M, Vermeesch JR, Devriendt K. Submicroscopic chromosomal imbalances detected by array-CGH are a frequent cause of congenital heart defects in selected patients. Eur Heart J. 2007 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aerts S, Lambrechts D, Maity S, Van Loo P, Coessens B, De Smet F, Tranchevent LC, De Moor B, Marynen P, Hassan B, et al. Gene prioritization through genomic data fusion. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(5):537–44. doi: 10.1038/nbt1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schutte BC, Bjork BC, Coppage KB, Malik MI, Gregory SG, Scott DJ, Brentzell LM, Watanabe Y, Dixon MJ, Murray JC. A preliminary gene map for the Van der Woude syndrome critical region derived from 900 kb of genomic sequence at 1q32-q41. Genome Res. 2000;10(1):81–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, Bjork BC, Knight AS, Watanabe Y, Howard E, de Lima RL, Daack-Hirsch S, Sander A, et al. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet. 2002;32(2):285–9. doi: 10.1038/ng985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krzywinski M, Bosdet I, Smailus D, Chiu R, Mathewson C, Wye N, Barber S, Brown-John M, Chan S, Chand S, et al. A set of BAC clones spanning the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(12):3651–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinds DA, Kloek AP, Jen M, Chen X, Frazer KA. Common deletions and SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):82–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad DF, Andrews TD, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Pritchard JK. A high-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):75–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, Scherer SW, Lee C. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(9):949–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarroll SA, Hadnott TN, Perry GH, Sabeti PC, Zody MC, Barrett JC, Dallaire S, Gabriel SB, Lee C, Daly MJ, et al. Common deletion polymorphisms in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):86–92. doi: 10.1038/ng1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, Feuk L, Perry GH, Andrews TD, Fiegler H, Shapero MH, Carson AR, Chen W, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444(7118):444–54. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Troge J, Alexander J, Young J, Lundin P, Maner S, Massa H, Walker M, Chi M, et al. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305(5683):525–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, Pertz LM, Clark RA, Schwartz S, Segraves R, et al. Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(1):78–88. doi: 10.1086/431652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuzun E, Sharp AJ, Bailey JA, Kaul R, Morrison VA, Pertz LM, Haugen E, Hayden H, Albertson D, Pinkel D, et al. Fine-scale structural variation of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2005;37(7):727–32. doi: 10.1038/ng1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kariyazono H, Ohno T, Ihara K, Igarashi H, Joh-o K, Ishikawa S, Hara T. Rapid detection of the 22q11. 2 deletion with quantitative real-time PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 2001;15(2):71–3. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2000.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkuraya FS, Saadi I, Lund JJ, Turbe-Doan A, Morton CC, Maas RL. SUMO1 haploinsufficiency leads to cleft lip and palate. Science. 2006;313(5794):1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1128406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sander A, Schmelzle R, Murray J. Evidence for a microdeletion in 1q32-41 involving the gene responsible for Van der Woude syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(4):575–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schutte BC, Basart AM, Watanabe Y, Laffin JJ, Coppage K, Bjork BC, Daack-Hirsch S, Patil S, Dixon MJ, Murray JC. Microdeletions at chromosome bands 1q32-q41 as a cause of Van der Woude syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84(2):145–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990521)84:2<145::aid-ajmg11>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rauch A, Pfeiffer RA, Leipold G, Singer H, Tigges M, Hofbeck M. A novel 22q11. 2 microdeletion in DiGeorge syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(2):659–66. doi: 10.1086/302235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayano S, Kure S, Suzuki Y, Kanno K, Aoki Y, Kondo S, Schutte BC, Murray JC, Yamada A, Matsubara Y. Novel IRF6 mutations in Japanese patients with Van der Woude syndrome: two missense mutations (R45Q and P396S) and a 17-kb deletion. J Hum Genet. 2003;48(12):622–8. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice R, Spencer-Dene B, Connor EC, Gritli-Linde A, McMahon AP, Dickson C, Thesleff I, Rice DP. Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(12):1692–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrer VL, Maeda T, Kawano Y. Characteristic distribution of immunoreaction for estrogen receptor alpha in rat ameloblasts. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2005;284(2):529–36. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greene RM, Nugent P, Mukhopadhyay P, Warner DR, Pisano MM. Intracellular dynamics of Smad-mediated TGFbeta signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2003;197(2):261–71. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuda T, Yamamoto T, Muraguchi A, Saatcioglu F. Cross-talk between transforming growth factor-beta and estrogen receptor signaling through Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(46):42908–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Representative diagrams of human chromosome 8 (A), 22 (B), 6 (C) and 10 (D) are illustrated at the bottom of each figure with cytogenetic bands and positions. The numbers at the top of each figure indicate DNA sequence position from hg17, May 2004 Assembly. Array-CGH results are displayed by plotting position of each BAC on the DNA sequence (X axis) against log2 (Test/Reference) values (Y axis). (A) A 9.1 Mb duplication of chromosome 8p21.3-8p12 and a 11.6 Mb deletion of chromosome 8q23.1-8q24.12 were identified from a subject who has lower lip pits, multiple congenital anomalies including oligodactyly with absence of a left toe, and abnormal neurodevelopment. (B) A 2.7 Mb deletion at chromosome 22q11.21 was found from a subject with cup shaped ears, a cleft palate and a thumb anomaly. (C) A 3.2 Mb deletion was identified at chromosome 6q25.1-25.2 from a subject with cleft lip (unilateral right) with cleft palate. (D) A 2.2 Mb deletion was found at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 from a subject with cleft lip without palate. The deleted regions were highlighted with black stripe on each chromosome diagram.

Supplemental Figure 2: Pedigree of the subject D (Table 1) who has cleft lip

Square and circle symbols represent male and female individuals, respectively. Affected individuals are shown with blackened symbols, and unaffected individuals are shown with white symbols. The subject and her mother were affected individuals in this family.

Supplemental Figure 3: A 2.2 Mb region at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 (A) and a 3.2 Mb at chromosome 6q25.1-25.2 (B) on UCSC Genome Browser

The horizontal bold lines represent BAC clones spanning at each region. Genes assigned in the region was displayed using “RefSeq Genes track” with thin horizontal line with short vertical lines. FGFR2 and ESR1 are identified at chromosome 10q26.11-26.13 and 6q25.1-25.2, respectively.