To the Editor:

There has been considerable recent interest in developing therapies for food allergy, an increasingly common and highly morbid disorder for which strict dietary elimination and ready access to epinephrine remain the standard of care.(1) While both oral immunotherapy (OIT)(2-4) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT)(5) have been shown to induce clinical desensitization to foods (reviewed in 6), no head-to-head comparative analysis of the two treatments has been published.

We conducted a retrospective study of two previously published protocols for peanut allergy(2,3). This new analysis includes additional subjects, compares the 12-month oral food challenge outcomes, and extends analysis of immunologic parameters out to 24 months. Eligible peanut-allergic subjects were recruited into one of two concurrent clinical trials: OIT (maintenance dose of 4000 mg/day and cumulative double-blind, placebo-controlled challenge (DBPCFC) dose of 5000 mg); or SLIT, (2 mg/day, and 2500 mg, respectively) [all quantities refer to peanut protein]. Although the optimal immunotherapy dose remains unknown, the doses chosen in these trials were based on preliminary data from pilot studies. Of note, unique properties of the oral mucosal immune response are hypothesized to account for SLIT’s efficacy at log-fold lower doses (reviewed in 7). Both trials utilized randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled designs. Mechanistic studies were performed longitudinally as previously described using blood drawn from subjects within 24 hours of their last immunotherapy dose.(2, 3) At 12 months, subjects underwent DBPCFC to assess clinical desensitization; OIT subjects received a maximal 5000 mg cumulative protein dose, and for safety reasons SLIT challenges were limited to 2500 mg (Online Repository Tables E1/E2). We compared laboratory data between OIT and SLIT at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months, as well as DBPCFC pass/fail outcomes, using the Wilcoxon signed rank test (STATA 12; College Station, TX) and Mann-Whitney U test (GraphPad Prism; La Jolla, CA).

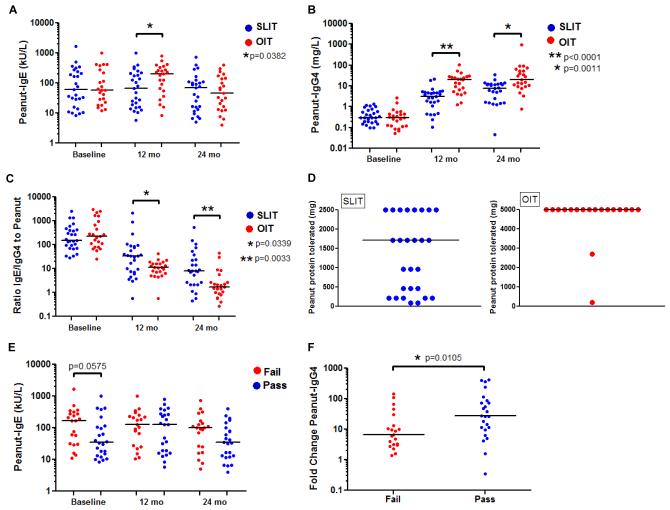

Twenty-three subjects on OIT and 27 subjects on SLIT were evaluated after receiving 2 years of treatment (Table 1). We did not undertake a formal comparison of safety parameters between the two studies, and upcoming interval reports of each study will include these data. However, there were no serious adverse events reported in either study. No SLIT and two OIT subjects (one active, one placebo) required four total doses of epinephrine for dose-related reactions. At baseline, the peanut-specific IgE was similar between OIT and SLIT subjects (Fig 1A). Twelve months of treatment led to higher median peanut-specific IgE levels in the OIT group compared to the SLIT group (204.5 kU/L versus 66.7 kU/L, p=0.0382); however, levels were not significantly different between the groups at 24 months (Fig 1A). While peanut-specific IgG4 increased over time in both groups (Fig 1B), the effect was greater with OIT at 12 (20.1 mg/L versus 3.1 mg/L) and 24 months (20.3 mg/L versus 7.9 mg/L, p<0.001). Although decreased in both groups, median peanut-specific IgE/IgG4 ratios were significantly lower at 12 and 24 months for subjects receiving OIT (Fig 1C). Thirty-four subjects (14 OIT, 20 SLIT) had basophil activation assessed by CD63 up-regulation at baseline and 12 months. After 12 months, a significantly lower percentage of CD63+ basophils was found in the OIT group compared with the SLIT group when stimulated with 100 (median 5.90% versus 21.50%) and 10−1 μg/mL (median 6.34% versus 30.75%) crude peanut extract (p<0.01). No between-group difference was seen after stimulation with weaker dilutions of 10−2 and 10−3 μg/mL crude peanut extract. Too few samples were obtained at 24 months to perform an analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline subject characteristics

| Peanut OIT | Peanut SLIT | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number evaluated | 23 | 27 | |

|

Median age at enrollment

(range) |

5.3 years (3-10) | 6.3 years (2-11) | 0.45 |

| Male | 13 (57%) | 21 (78%) | 0.14 |

| Race | 21 White 2 Black |

26 White 1 Asian |

0.59 |

|

Median peanut-specific IgE

(kU/L), range |

58.5 (12-985) | 61.7 (8.5-1636) | 0.67 |

|

Median skin prick test (mm),

range |

14.5 (7-26) | 11.5 (3.5-23.5) | 0.04 |

| Asthma | 13 (57%) | 14 (52%) | 0.78 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 17 (74%) | 21 (78%) | >0.99 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 16 (70%) | 19 (71%) | >0.99 |

| Other food allergy | 14 (61%) | 9 (33%) | 0.09 |

FIG 1.

A and B, Change in serum peanut-IgE and peanut-IgG4 (SLIT/OIT). C, IgE/IgG4 ratio to peanut (SLIT/OIT). D, Cumulative amount tolerated during DBPCFC (SLIT/OIT). E, Serum peanut-IgE (Pass/Fail). F, Fold change in serum peanut-IgG4 from baseline to 12 months (Pass/Fail). Scatter plots show individual data with a line designating the median.

Eighteen subjects on OIT and 27 subjects on SLIT underwent 12 month desensitization DBPCFCs, results of which are shown in Figure 1D. Despite differences in DBPCFC protocols, SLIT subjects reacted at lower eliciting dose thresholds. A Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the difference in proportions and relative risk for passing or failing the DBPCFC according to treatment group. The difference in proportions was statistically significant (p=0.002), with OIT-treated subjects 3 times more likely to pass the 12 month desensitization DBPCFC than SLIT-treated subjects (RR=3.00, 95% CI 1.64-5.49).

In an attempt to identify candidate biomarkers, we combined all SLIT and OIT subjects and then categorized them by “pass” or “fail” based upon their ability to complete the DBPCFC without symptoms. Consistent with other studies, subjects passing the 12 month desensitization DBPCFC tended to have lower baseline peanut-specific IgE levels (34.6 kU/L versus 167 kU/L, p=0.0575) (Fig 1E). Peanut-specific IgG4 was increased by 27-fold in the “pass” group compared to a 6.5-fold increase in the “fail” group (p=0.01; Fig 1F). Interestingly, the percentage of CD63+ basophils was significantly lower at 12 months in the “pass” group compared with the “fail” group when stimulated with 100 (median 5.90% versus 21.50%) and 10−1 μg/mL (median 6.34% versus 34.75%) crude peanut extract (p<0.01). Again no differences were seen between groups after stimulation with weaker dilutions. Skin prick tests decreased over time in all subjects. Wheal size, serum peanut-specific IgA and peanut-specific IgG, and CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T-regulatory cells were not significantly different between the OIT and SLIT groups or the “pass” and “fail” groups.

In summary, our results suggest that after two years of treatment, OIT produces greater immunologic changes than SLIT in peanut-allergic children. Specifically, peanut OIT resulted in greater changes in peanut-specific IgE, IgG4, and IgE/IgG4 ratio as well as basophil activation. In addition, eliciting dose thresholds were lower and more variable during DBPCFC at 12 months in SLIT-treated subjects, compared to OIT-treated subjects. Subjects who passed the DBPCFC tended to have lower baseline peanut-IgE levels, in addition to a larger fold change in peanut-IgG4 and less basophil activation at 12 months. The major limitation of this study is that it was not a randomized prospective study designed to directly compare the two modalities with a uniform protocol and consecutive enrollment. It is important to also note that interim clinical endpoints measured after only 12 months of immunotherapy likely do not provide a full assessment of the efficacy of either method. Further research is needed to determine the optimal length of treatment, dose, and ideal immunotherapy candidate for each modality.

Supplementary Material

Table E1 – Dosing schedule for OIT DBPCFC

Table E2 – Dosing schedule for SLIT DBPCFC

Capsule summary.

This is the first study to directly compare immunologic and clinical data following 2 years of sublingual or oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. We observed greater changes in humoral and basophil responses, and more uniform clinical responses among OIT-treated subjects.

Acknowledgments

Funding support provided by the NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine R01–AT004435–03, NIH grant R01-AI06874-01A1, NIH National Center for Research Resources UL1RR024128, NIH Training grant 5T32–AI007062–32, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology/Food Allergy Initiative, Gerber Foundation, Dorothy and Frank Robins Family, the National Peanut Board, Howard Gittis Memorial 3rd Year/4th Year Fellowship/Instructor Award (J.A.B.), and the Wallace Research Foundation (WRF2010.01). Additional support for the project was provided by Grant Number UL1RR024128 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Abbreviations

- DBPCFC

double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge

- OIT

oral immunotherapy

- SLIT

sublingual immunotherapy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6):1105–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.008. Epub 2010/12/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kemper A, Steele P, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: Clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;127(3):654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skripak JM, Nash SD, Rowley H, Brereton NH, Oh S, Hamilton RG, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Dec;122(6):1154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burks AW, Jones SM, Wood RA, Fleischer DM, Sicherer SH, Lindblad RW, et al. for the Consortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 19;367(3):233–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim EH, Bird JA, Kulis M, Laubach S, Pons L, Shreffler W, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: Clinical and immunologic evidence of desensitization. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;127(3):640–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narisety SD, Keet CA. Sublingual vs oral immunotherapy for food allergy: identifying the right approach. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1977–89. doi: 10.2165/11640800-000000000-00000. doi: 10.2165/11640800-000000000-00000. PubMed PMID: 23009174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novak N, Bieber T, Allam JP. Immunological mechanisms of sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy. 2011 Jun;66(6):733–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table E1 – Dosing schedule for OIT DBPCFC

Table E2 – Dosing schedule for SLIT DBPCFC