Abstract

African Americans, compared with white Americans, underutilize mental health services for major depressive disorder. Church-based programs are effective in reducing racial disparities in health; however, the literature on church-based programs for depression is limited. The purpose of this study was to explore ministers’ perceptions about depression and the feasibility of utilizing the church to implement evidence-based assessments and psychotherapy for depression. From August 2011 to March 2012, data were collected from three focus groups conducted with adult ministers (n = 21) from a black mega-church in New York City. Using consensual qualitative research to analyze data, eight main domains emerged: definition of depression, identification of depression, causal factors, perceived responsibilities, limitations, assessment, group interpersonal psychotherapy, and stigma. A major finding was that ministers described depression within a context of vast suffering due to socioeconomic inequalities (e.g., financial strain and unstable housing) in many African American communities. Implementing evidence-based assessments and psychotherapy in a church was deemed feasible if principles of community-based participatory research were utilized and safeguards to protect participants’ confidentiality were employed. In conclusion, ministers were enthusiastic about the possibility of implementing church-based programs for depression care and emphasized partnering with academic researchers throughout the implementation process. More research is needed to identify effective, multidisciplinary interventions that address social inequalities which contribute to racial disparities in depression treatment.

Keywords: African Americans, Church, Depression, Mental health services, Community-based participatory research

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most disabling and prevalent psychiatric disorders in the USA.1 Epidemiological studies show that 14–17 % of Americans are diagnosed with MDD at some point in their lives.1,2 African Americans, compared with white Americans, have slightly lower or similar rates of lifetime MDD.2–4 Nevertheless, African Americans with MDD have a more persistent and debilitating course of illness relative to their white counterparts.3,5 Despite national initiatives to reduce racial disparities in mental health care,6,7 African Americans continue to under-utilize mental health services compared with white Americans.8–11 Factors associated with these disparities include stigma of mental illness,12 lack of access,13 financial cost,13, and distrust of providers.14 Given the disabling nature of MDD and enduring racial disparities in care, identifying alternative treatment strategies is a pressing public health priority.

Research suggests that community-based interventions hold promise for reducing racial disparities in depression treatment.15,16 The Black Church, classically defined as the set of seven predominantly African American denominations of the Christian faith,17 is a prominent, easily accessible, and trusted institution in many African American communities.17,18 The Black Church has a history of confronting racial disparities by providing health and social services to community members.17,19 Church-based health programs are designed to provide measurable benefits to individuals through education, screening, and treatment.19,20 Such programs have effectively improved health outcomes for cancer screening,21–23 dietary change,21,24–28 weight loss, 21,26,28,29 smoking cessation,30 and diabetes treatment.31 However, the literature on church-based programs for mental disorders is limited. Our group conducted a systematic review of church-based programs for mental disorders among African Americans and found only eight empirical studies.32 Depression was the primary outcome in only one of these studies.33

Clergy provide an invaluable role in the US mental health care delivery system.34 Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey, a nationally representative general population survey of 8,098 adults in the USA, show that a higher percentage of people sought help for mental disorders from clergy (25 %) compared with psychiatrists (16.7 %) or general medical doctors (16.7 %).34 African American ministers, in particular, are considered trusted “gatekeepers” for referring community members to mental health professionals.35,36 Neighbors et al. found that 50 % of African Americans utilizing only one source of mental health care sought help from clergy providers.35 Despite the indispensable mental health services provided by African American ministers, qualitative data about their roles in depression care are scarce.37 Focus groups are an effective qualitative research method for investigating complex behaviors and can help identify emerging issues for intervention planning.38,39

Thus, the purpose of this study was to conduct focus groups with ministers from one of the largest black churches in the US to learn their views on depression and the feasibility of implementing church-based programs for MDD. We specifically sought to understand the minister’s perspectives on distributing a validated depression screening assessment40 to parishioners in the church. We also explored the ministers’ opinion about conducting an evidence-based treatment for MDD, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) delivered in a group,41–43 at the church. This intervention was selected because it has been shown to be effective among similar populations,44,45 including two studies conducted in groups with community members in rural Uganda.46–48

Methods

Sample and Recruitment

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. This study was conducted at a predominantly African American, Methodist denomination, mega-church in New York City. Mega-churches are defined as having at least 2,000 worshippers throughout the course of a weekend. As such, there are over 1,200 mega-churches in the USA.49 Persons identified as ministers (n = 65) at the church were eligible to participate in the focus group study regardless of race/ethnicity or gender. Additional inclusion criteria were age 18 years and older, English speaking, and able to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria included inability to provide signed informed consent and any significant medical condition compromising ability to participate. Men and women were recruited equally.

Study participants were recruited from a convenience sample during the ministers’ regularly scheduled, monthly administrative meeting on 11 June 2011. The research team gave a detailed power-point presentation that described the study objectives and process for conducting the focus groups. A total of 32 ministers initially agreed to participate in the study. However, eleven of these ministers decided not to participate due to scheduling conflicts, resulting in 21 of 32 eligible ministers who ultimately participated (65.6 %). All ministers who participated provided signed informed consent. No demographic information was collected from the ministers who did not participate in the focus groups.

Procedure

A semi-structured, open-ended question guide based on the study objectives was developed. Prior to conducting the focus groups, researchers modified the question guide based on feedback from members of the church’s Health Ministry, a committee of congressional members who promote health-related activities at the church.50 The final question guide is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Question guide utilized for minister focus groups

| Tell me a little about your responsibilities as a minister |

| How long have you been a minister? |

| What does the term “depression” mean to you? |

| Do you believe depression is a disease? |

| What factors do you believe contribute to depression? |

| Do you believe other factors contribute to depression? (Biological, psychological, spiritual (i.e., sins), and others?) |

| What are the main mental health/emotional concerns or issues of members in your church? |

| What do you consider mental/emotional distress (impairment)? |

| How do you identify if a member is in distress? |

| If a member comes to you in distress, how do you help them? |

| Do you believe you can help a church member who is in mental/emotional distress? |

| How do you determine if a church member needs help for depression outside of the church? |

| If a church member needs help for depression outside the church, how do you determine the type of help they need? |

| How do you make a referral? |

| To whom/where do you refer them? (Social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, primary care doctor, or others?) |

| Do you believe some psychological problems require medications? |

| If so, what disorders require medications? |

| What are your views on people who take medications for depression? |

| Do you believe that some members avoid seeking help for depression? |

| If members avoid getting help for depression, why do you think that is? |

| Do you believe it would be a good idea to distribute a mental health survey about depression to members in your church? |

| What do you believe would be the challenges of distributing a mental health survey in your church? |

| How do you overcome these challenges? |

| How do you keep material confidential? |

| How do you present a research study to a church congregation? |

| Do you believe it would be a good idea to conduct group therapy for depression in your church? |

| What do you believe are the challenges of conducting group therapy for depression in your church? |

| How do you overcome these challenges? |

| How do you keep group material confidential? |

| How do you deal with legal problems related to treatment? |

Each of the focus groups (n = 3) was facilitated by the primary investigator, an African American male psychiatrist. All focus groups were conducted on-site at the church in the pastoral library between 13 August 2011 and 10 March 2012. The number of participants in each focus group ranged from three to ten ministers. The group facilitator initiated the open-ended interview; however, the specific content and order of the discussion was driven by participants’ responses.14,51 Research assistants took detailed field notes to record the flow of discussion, seating arrangement, and nonverbal gestures of participants. Each focus group lasted 90 min and was audiorecorded. Each minister received a $30 fee upon completing the study.

Immediately after each focus group, investigators met to review field notes, comment on group dynamics, and download the audio-recording to a password protected laptop computer. Each focus group was then transcribed verbatim into Microsoft Word. Identifying information was removed from all of the transcripts to protect confidentiality of the participants. Members of the research team received a copy of the transcript to review prior to commencing data analysis.

Data Analysis

Data from the focus groups were analyzed via methods of consensual qualitative research.52–54 This analytic process involves three essential steps: (1) identifying domains—topics used to group data, (2) developing core ideas—summary of the data that captures what was said in few words and greater clarity, and (3) a cross-analysis—used to construct common themes across groups.53 Two researchers coded all of the transcripts and identified domains. Discrepancies were argued to consensus among research team members through discussions led by the primary investigator. A senior investigator, who has extensive experience conducting focus groups with African Americans and analyzing qualitative data,55–58 served as external auditor to ensure that raw data had been coded accurately. We identified three overarching themes: concept of depression, ministers’ role in depression care, and church-based depression services. After conducting cross-analyses across the three focus groups, eight primary domains emerged.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The mean age of ministers (n = 21) was 54 years (SD = 11.6), and the majority of ministers were female (85.7 %). In terms of racial/ethnic self-identification, 17 ministers were African American, two were Jamaican, one identified as “Other,” and one did not respond. Most of the ministers were married (52.4 %) and had a master’s degree or higher (57.1 %). Characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of minister focus group participants (n = 21)

| Minister characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) | 54 (11.6) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 18 (85.7) |

| Men | 3 (14.3) |

| Ethnicitya | |

| African American | 17 (81.0) |

| Jamaican | 2 (9.5) |

| Other | 1 (4.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 11 (52.4) |

| Never married | 5 (23.8) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 5 (23.8) |

| Education | |

| High School | 1 (4.8) |

| Some College | 1 (4.8) |

| Completed College | 7 (33.3) |

| Master’s Degree or Higher | 12 (57.1) |

aOne participant did not respond

Concept of Depression

Definition

Ministers defined depression as a common and serious problem among African Americans that occurs in a context of vast suffering. Women and youth were cited as high-risk groups for becoming depressed. A common description of depression was a feeling of being “hopeless” or “helpless.” People with depression were described as “trapped” or “stagnant.” One minister defined depression as follows:

“It’s various degrees, levels, but the easiest working definition for me is a negative triad – negative view of self, negative of others, and negative view of future and world. Everywhere I look; everywhere I see; it doesn’t look good.”

Most ministers asserted that depression is a disease, although support for this definition was not unanimous. Other ministers argued that only “some depression” constitutes a disease state. Surprisingly, only one minister defined depression solely in reference to God, describing depression as:

“…a greater opportunity for the depressed person to work on the relationship with God, and for God, in return, to meet the needs that the depressed person has…”

Identification

Duration and severity of symptoms were proposed as ways to distinguish depression from transient periods of sadness or “environmental” stress. Many ministers also identified various types of depression, such as “seasonal depression” and “dysthymia.” Several ministers identified people with depression as crossing a threshold:

“Whereas the person who is really depressed and actually struggling doesn’t even know where to start; that not being able to see your way out of it. The duration and that person’s reaction to what they are in, I would say are ways to distinguish.”

Causal Factors

Though many causes were listed, socioeconomic conditions and conflict in interpersonal relationships were named as the main causal factors for depression. Specifically, financial hardship, unstable employment, broken family systems, and loss of a loved one were named as factors causing depression. One minister stated that the primary mental health concerns facing church congregants were:

“…not having money, not being able to meet your obligations, [and] having people want to take your house because you can’t make the payment.”

“Life circumstance” and “stress” of the being African American in the USA were also described as factors contributing to depression. Ministers illustrated how the adverse effects of institutional racism, political policies, and unfavorable environmental conditions contributed to depression:

“Effects of slavery, then white supremacy, racism, and all things that we talk about in the black community; all that we have to deal with in our community is systemic. So, even though you may play by all the rules, and you may get the degrees and do everything that’s required of you, and then you don’t get that payoff in the end, you can go into a state of depression.”

Ministers stated that biologic factors such as low serotonin levels, sleep deprivation, and “chemical issues” can lead to depression. Many cited “trauma,” particularly childhood trauma, as causing depression. Crises of identity were cited as major causes of depression among adolescents.

Minister’s Role in Depression Care

Perceived Responsibilities

Ministers stated that they have multiple responsibilities in providing depression care. The ministers currently utilize prayer, “faith healing,” and quoting Scriptures to counsel congregant members. The ministers outlined a process by which parishioners in need can speak briefly with a minister immediately after the main Sunday service. Providing short-term counseling to parishioners who are experiencing psychological distress and referring parishioners to mental health professionals were also identified as ministers’ responsibilities. A summary of these responsibilities is:

“…to stop the bleeding and use discernment and be able to give them [parishioners] direction. I believe, we all believe in Biblical principle, but we have to use practical application. You have to use discernment and know when this is out of your hands and you guide them off and give them recommendations to get themselves practical, clinical help.”

Limitations

The ministers reported that time constraints and lack of a formal procedure for counseling and referring parishioners are factors currently limiting their ability to provide depression care. Ministers felt like they were “barely scratching the surface” of the real issues causing a person distress. Ministers acknowledged it was difficult to assess a parishioner thoroughly:

“I found myself as a new minister, being sort of overwhelmed with that, because my heart was aching for them [parishioners]. It was not very much that I could really do in terms of just prayer and listening; kind of talk and console and make a referral.”

Due to lack of knowledge about mental illness, some ministers expressed concern over the possibility of doing more harm to depressed parishioners than helping them. Some ministers admitted feeling “unequipped” to handle severe cases of depression. Conversely, many ministers could not describe a systematic process by which to refer parishioners to a higher level of care outside the church:

“I’m just not aware of … some processes, a procedure to follow, if there were someone to see these individuals. But as an individual minister, I don’t know if I’m the right person.”

Feasibility of Church-Based Depression Services

Assessment

Ministers stressed the importance of keeping responses on the depression screening instrument anonymous and brief. The ministers’ major concerns with the health survey were how it would be distributed and why socioeconomic data were being collected. Ministers objected to distributing the survey to congregants during Sunday services, because they thought it would disrupt the flow of service and might cause respondents to falsify results due to social pressure. Instead, they suggested distributing the assessment in “smaller settings” like the church choir or Men’s Bible Study. Ministers and academic researchers collaborating to distribute the screening instrument and reporting the results back to the church were deemed crucial to gain the trust of parishioners:

“You have a team of ministers that have signed up for this, maybe put us in rotation to go out and support you or whoever is going to be handing them out, so we can explain it. So it’s a familiar face, it’s not like outsiders coming and using us as guinea pigs …”

“And so you definitely want to give them the results, so that they are part of the process, and they understand the results. Because you are actually educating people when you give them results.”

Group Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Ministers asserted that Group IPT would be feasible to conduct in a church building. The ministers equated Group IPT to a support group, “Grief Share,” which is currently conducted weekly at the church:

“We do Grief Share, as a Christian-based, grief support group. People were very open, and not that we have any clinicians in there, but the program was developed by some clinicians and by some Christians. And I think it’s very helpful, and it’s a safe space for people that are going through clinical issues or grief to interject how they really feel …”

However, protecting parishioner’s confidentiality and protecting the church against liability were identified as the main challenges to providing Group IPT in the church. A minister summarized these risks:

“… someone may breach that confidentiality. There may be some devastating effects behind that, because if the person is already depressed and now you expose them, and they may do something even worse to themselves or someone else, which would leave the church open to liability.”

Stigma

Stigma cut across all of the over-arching themes, i.e., concept of depression, ministers’ role in depression care, and feasibility of church-based depression services. Ministers suggested that depression may be more stigmatized in the church community than the lay public due to parishioners’ concern that depression signifies an erosion of one’s relationship with God and failure to be a “good Christian.” For instance:

“When people are transparent, they’re not made to be comfortable to be transparent, because either they are ostracized or either they’re labeled, or either they don’t have enough faith, or they’re not spiritual enough. So, people have learned to play the church game.”

The stigma associated with depression was cited as a barrier in the ministers’ ability to have a prominent role in care. Ministers suggested that identifying depression in a parishioner would be met with resistance:

“It’s very hard for people to accept. When people come to you, for you to say, you know, ‘Are you experiencing depression?’ They don’t want to hear that.”

Due to the stigma associated with psychotherapy, one minister suggested calling the group intervention, “Coping with the Vicissitudes of Life.” Ministers asserted that changing the name would help with recruitment, because “if you say anything about group therapy, they (community members) are not coming.”

Discussion

The ministerial focus groups presented here represent the first phase of a study designed to address racial disparities in depression treatment via church-based programs. The second phase of the study involves distributing a depression screening assessment among parishioners.40 The final phase involves conducting IPT in a group at the church.41,46,47 Since African Americans have higher rates of church attendance and religiosity compared with other racial-ethnic groups,59,60 church-based programs may reach a large cohort of African Americans who currently do not utilize mental health services.15,16,49

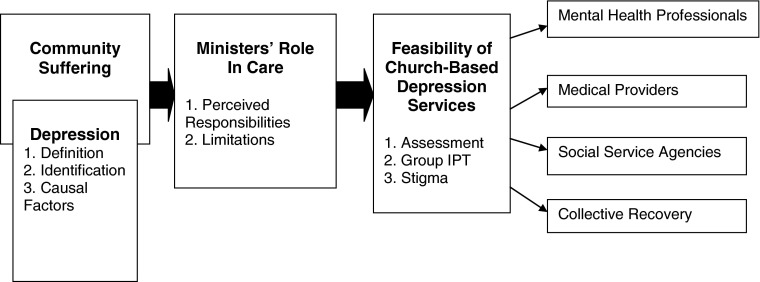

Overall, the ministers were enthusiastic about expressing their perspectives on depression and stated that providing church-based depression services is feasible. A pathway of care representing our major domains is illustrated in Figure 1. The pathway emphasizes how ministers’ role as “gatekeeper” can be leveraged to refer parishioners to church-based depression screening and Group IPT, mental health professionals, other medical providers, and social service agencies. To better equip them in their gate-keeping role, we suggest that ministers be formally trained about the signs and symptoms of major depression.49,61 Such training was successfully used to educate clergy in a domestic violence preventive program.61 Educating ministers and having them disseminate that knowledge to community members could help reduce some of the stigma associated with depression. We also suggest that clergy develop a formal, systematic process for documenting which parishioners are referred to mental health professionals. A crucial part of this process would involve building trust between ministers and local mental health providers.

Figure 1.

Pathway of depression care that summarizes results of ministers’ focus groups.

An important finding was that ministers described depression within a context of vast suffering in the African American community. Consistent with prior studies, ministers attributed depression among African Americans to harsh socioeconomic conditions.37,62–64 As such, interventions that solely target depressive symptoms may be insufficient to address the broader issues of chronic stress and suffering.62 More research is needed to identify effective, interdisciplinary interventions which address the numerous factors contributing to suffering in many African American communities.58,65 One possible solution is to promote “collective recovery,” a process of rebuilding social connections in under-served communities that lead to individual and group recovery.65,66 Collective recovery was effectively utilized in New York City to help communities cope with the aftermath of the terroristic attack of 9/11.66

The ministers viewed the screening assessment as a way to educate parishioners about the symptoms of depression. Ministers emphasized the importance of collaborating with academic researchers to distribute the assessment to parishioners in small group settings. By administering the survey in smaller groups (i.e., the church choir), ministers would be able to more easily address parishioners’ concerns about the need to collect socioeconomic data. They also stressed the necessity of getting buy-in from the lead pastor and identifying members of the ministerial staff who would consistently advocate for implementing the assessment.67 Garnering support of key intra-organizational leaders is highly correlated with the success of church-based health programs.32,67–70

Regarding IPT in a group, the ministers emphasized similarities between Group IPT and a grief support group which is currently conducted at the church. Group IPT provided in a church can appeal to African Americans’ cultural preferences for depression treatment. For example, African Americans in clinical samples express a preference for psychotherapy over taking medications to treat depression71 and are three more times likely than white adults to cite spirituality as an extremely important part of depression care.72 The ministers’ major concerns about conducting Group IPT were about the possibility of breaching confidentiality and liability against the church. To protect participant confidentiality and reduce stigma, ministers recommended that Group IPT be conducted at a church building located one block away from the current main sanctuary. Collaborating with community members to identify flexible ways to deliver Group IPT was successfully completed among community members in Uganda.73 In addition to these recommendations, it appears prudent for churches and researchers to consult with legal experts prior to implementing evidence-based psychotherapy on church grounds.

We must acknowledge the study’s limitations. First, our findings may have limited generalizability to other settings. Our study was conducted with a relatively small sample (n = 21) of highly educated ministers from one church that has over 2,000 members in an urban setting. Future studies should be conducted with a greater number of churches that vary in size, level of minister education, and geographic location. Second, we assessed ministers’ perspectives about a specific depression screening assessment and treatment. As such, we cannot comment on the ministers’ perceptions of utilizing other depression assessments or interventions. Third, since the primary investigator was also lead facilitator of the focus groups, participants’ may have been subject to desirability effects.74,75 Prior to conducting the study, our team decided that the risk of possible desirability effects would be outweighed by the benefit of the primary investigator’s visibility and engagement with the ministers throughout the study, leading to a more trusting relationship. Building trust is an essential process of community-based interventions.76–78

In conclusion, reducing racial disparities in depression care is a multi-layered problem, for which there is no single solution. We recognize that there may be vulnerable populations (i.e., black adolescent males) that are unlikely to be reached by church-based mental health programs.32 However, African American ministers play an essential role in providing mental health services to underserved communities. Partnering with church leaders via principles of community-based participatory research68,76,78 appears essential for implementing and testing church-based depression services. Additional research is needed to develop interdisciplinary, collaborative interventions to address the socioeconomic factors that contribute to suffering and mental health disparities among African Americans.

Acknowledgements

In the past 2 years, Dr. Hankerson was supported by grant 5-T32 MH015144 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and grant #17694 from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD). Dr. Lukachko received support from a grant 5-T32-MH13043 from the NIMH. Dr. Weissman received funding from the NIMH, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), NARSAD, the Sackler Foundation, the Templeton Foundation, and the Interstitial Cystitis Association and receives royalties from the Oxford University Press, Perseus Press, the American Psychiatric Association Press, and MultiHealth Systems. None of these sources conflict with the content of this manuscript. The remaining authors have no relevant research support and no conflicts of interests to disclose. The results of this manuscript, in part, were presented at a symposium during the 64th Institute on Psychiatric Services Conference in New York, New York on Friday, 5 October 2012.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satcher D. The initiative to eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities is moving forward. Public Health Rep. 1999;114(3):283–287. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.3.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satcher D, Higginbotham EJ. The public health approach to eliminating disparities in health. Am J Publ Health. 2008;98(3):400–403. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thurston IB, Phares V. Mental health service utilization among African American and Caucasian mothers and fathers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(6):1058. doi: 10.1037/a0014007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(11):1264–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Löwe B, Schenkel I, Carney-Doebbeling C, Göbel C. Responsiveness of the PHQ-9 to psychopharmacological depression treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):62–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menke R, Flynn H. Relationships between stigma, depression, and treatment in white and African American primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(6):407–411. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a6162e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hines-Martin V, Malone M, Kim S, Brown-Piper A. Barriers to mental health care access in an African American population. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2003;24(3):237–256. doi: 10.1080/01612840305281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson VLS, Bazile A, Akbar M. African Americans’ perceptions of psychotherapy and psychotherapists. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2004;35(1):19–26. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.35.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells K, Miranda J, Bruce ML, Alegria M, Wallerstein N. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells KB, Miranda J, Bauer MS, et al. Overcoming barriers to reducing the burden of affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(6):655–675. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatters LM. Religion and health: public health research and practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ransdell LB. Church-based health promotion: an untapped resource for women 65 and older. Am J Heal Promot. 1995;9(5):333–336. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell MK, James A, Hudson MA, et al. Improving multiple behaviors for colorectal cancer prevention among African American church members. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):492–502. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan N, Fox SA, Derose KP, Carson S. Maintaining mammography adherence through telephone counseling in a church-based trial. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(9):1468–1471. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.9.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts RC, Hollenberg JA. Increasing mammography practice by African American women. Cancer Practice. 1999;7(2):78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1390–1396. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, et al. Body and soul: a dietary intervention conducted through African-American Churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, et al. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Heal Psychol. 2005;24(4):339–348. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, et al. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through Black churches: results of the Eat for Life trial. J Inf. 2001;91(10):1686–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resnicow K, Taylor R, Baskin M, McCarty F. Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obesity. 2005;13(10):1739–1748. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young DR, Stewart KJ. A church-based physical activity intervention for African American women. Fam Commun Health. 2006;29(2):103–117. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voorhees CC, Stillman FA, Swank RT, Heagerty PJ, Levine DM, Becker DM. Heart, body, and soul: impact of church-based smoking cessation interventions on readiness to quit. Prev Med. 1996;25(3):277–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boltri JM, Davis-Smith M, Zayas LE, et al. Developing a church-based diabetes prevention program with African Americans. The Diabetes Educator. 2006;32(6):901–909. doi: 10.1177/0145721706295010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hankerson SH, Weissman MM. Church-based health programs for mental disorders among African Americans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(3):243–249. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mynatt S, Wicks M, Bolden L. Pilot study of INSIGHT therapy in African American women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22(6):364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neighbors HW, Musick MA, Williams DR. The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(6):759–777. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young JL, Griffith EE, Williams DR. The integral role of pastoral counseling by African-American clergy in community mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(5):688–692. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramer TL, Blevins D, Miller TL, Phillips MM, Davis V, Burris B. Ministers’ perceptions of depression: a model to understand and improve care. J Relig Health. 2007;46(1):123–139. doi: 10.1007/s10943-006-9090-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shelley D, Cantrell MJ, Moon-Howard J, Ramjohn DQ, VanDevanter N. The $5 man: the underground economic response to a large cigarette tax increase in New York City. Am J Publ Health. 2007;97(8):1483–1488. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan D. Focus groups. Ann Rev Sociol. 1996;22:129–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidair HB, Boccia AS, Johnson JG, et al. Depressed parents’ treatment needs and children’s problems in an urban family medicine practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(3):317–321. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC. Interpersonal psychotherapy. Current Status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(8):599–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950080011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weissman MM. Recent non-medication trials of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10(1):117–122. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grote NK, Bledsoe SE, Swartz HA, Frank E. Feasibility of providing culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for antenatal depression in an obstetrics clinic: a pilot study. Res Soc Work Pract. 2004;14(6):397–407. doi: 10.1177/1049731504265835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shanok A, Miller L. Depression and treatment with inner city pregnant and parenting teens. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2007;10(5):199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty KF, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes randomised controlled trial. British J Psychiatry. 2006;188(6):567–573. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3117–3124. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clougherty KF, Verdeli H, Mufson LH, Young JF. Interpersonal psychotherapy: effectiveness trials in rural Uganda and New York City. Psychiatr Ann. 2006;36(8):566–572. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bopp M, Webb B. Health promotion in megachurches: an untapped resource with megareach? Health Promot Pract. 2012; 13(5): 679–686. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Austin S, Harris G. Addressing health disparities: the role of an African American health ministry committee. Soc Work Public Health. 2011;26(1):123–135. doi: 10.1080/10911350902987078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW. Focus groups: theory and practice. Vol 20. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007.

- 52.Hill C, Thompson B, Williams E. A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Couns Psychol. 1997;25(4):517–572. doi: 10.1177/0011000097254001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hill CE, Knox S, Thompson BJ, Williams EN, Hess SA, Ladany N. Consensual qualitative research: an update. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):196–205. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knox S, Hess SA, Williams EN, Hill CE. "Here’s a little something for you": how therapists respond to client gifts. J Couns Psychol. 2003;50(2):199–210. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE, III, Haynes K, Gross S. Black women and AIDS prevention: a view towards understanding the gender rules. J Sex Res. 1990;27(1):47–64. doi: 10.1080/00224499009551541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fullilove M, Fullilove R. Stigma as an obstacle to AIDS action. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42(7):1117–1129. doi: 10.1177/00027649921954796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green LL, Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE. Stories of spiritual awakening: the nature of spirituality in recovery. J Subst Abus Treat. 1998;15(4):325–331. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fullilove MT, Green L, Fullilove RE. Building momentum: an ethnographic study of inner-city redevelopment. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(6):840–844. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.6.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jayakody R, Levin JS. Black and White differences in religious participation: a multisample comparison. J Sci Study Relig. 1996;35(4):403–410. doi: 10.2307/1386415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor RJ, Mattis J, Chatters LM. Subjective religiosity among African Americans: a synthesis of findings from five national samples. J Black Psychol. 1999;25(4):524–543. doi: 10.1177/0095798499025004004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tripp M, Burleigh D, Wolff DA, Gadomski A. Training clergy: the role of the faith community in domestic violence prevention. J Relig Abuse. 2001;2(4):47–62. doi: 10.1300/J154v02n04_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams DR. Black-White differences in blood pressure: the role of social factors. Ethn Dis. 1992;2(2):126–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9 Suppl):S29–37. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fullilove MT, Hernandez-Cordero L, Madoff JS, Fullilove RE., 3rd Promoting collective recovery through organizational mobilization: the post-9/11 disaster relief work of NYC RECOVERS. J Biosoc Sci. 2004;36(4):479–489. doi: 10.1017/S0021932004006741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hernandez-Cordero LJ, Fullilove MT. Constructing peace: helping youth cope in the aftermath of 9/11. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3 Suppl):S31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval. 2005;26(3):320–347. doi: 10.1177/1098214005278752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marcus M, Walker T, Swint J, et al. Community-based participatory research to prevent substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in African-American adolescents. J Interprofessional Care. 2004;18(4):347–359. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Voorhees CC, Stillman FA, Swank RT, Heagerty PJ, Levine DM, Becker DM. Heart, body, and soul: impact of church-based smoking cessation interventions on readiness to quit. Prev Med. 1996;25(3):277–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Francis SA, Liverpool J. A review of faith-based HIV prevention programs. J Relig Health. 2009;48(1):6–15. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, Ford DE, Powe NR. How important is intrinsic spirituality in depression care? A comparison of white and African-American primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):634–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verdeli H, Clougherty K, Bolton P, et al. Adapting group interpersonal psychotherapy for a developing country: experience in rural Uganda. World Psychiatry. 2003;2(2):114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hollander JA. The social contexts of focus groups. J Contemp Ethnogr. 2004;33(5):602–637. doi: 10.1177/0891241604266988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilkinson S. Focus groups in health research. J Health Psychol. 1998;3(3):329–348. doi: 10.1177/135910539800300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Minkler M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S81–S87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]