Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has been associated with adverse physical, psychoemotional, and sexual health, and African American women are at higher risk for experiencing IPV. Considering African American women predominantly have African American male partners, it is essential to identify factors associated with IPV perpetration among African American men. The present study examined attitudes toward IPV, ineffective couple conflict resolution, exposure to neighborhood violence, and the interplay of these factors as predictors of IPV perpetration. A community sample of 80 single, heterosexual, African American men between 18 and 29 years completed measures assessing sociodemographics, attitudes towards IPV, perceived ineffective couple conflict resolution, exposure to neighborhood violence, and IPV perpetration during the past 3 months. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses, with age, education, and public assistance as covariates, were conducted on 65 men who reported being in a main relationship. Couple conflict resolution and exposure to neighborhood violence moderated the relation between attitudes supporting IPV and IPV perpetration. Among men who reported high ineffective couple conflict resolution and high exposure to neighborhood violence, IPV perpetration increased as attitudes supporting IPV increased. The findings indicated that interpersonal- and community-level factors interact with individual level factors to increase the risk of recent IPV perpetration among African American men. While IPV prevention should include individual-level interventions that focus on skills building, these findings also highlight the importance of couple-, community-, and structural-level interventions.

Keywords: African–American, Intimate partner violence, Conflict resolution, Neighborhood, Community violence

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is considered a serious public health concern and is associated with both adverse health outcomes and high-risk sexual behaviors among diverse groups of women.1–3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),4 IPV is defined as “physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse.” Experiences of IPV can adversely affect women’s physical and psychological health.5–8 Additionally, IPV has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2,9–12 In the United States, the estimated total cost for medical and mental health services related to IPV each year is approximately $4.1 billion and nearly $1.8 billion for loss of productivity (e.g., lost time from work).13

Given the multiple negative health and economic costs of IPV, it is important to examine factors associated with male perpetration of IPV towards female partners. Previous research has indicated that attitudes towards IPV are an important predictor of male perpetration of partner violence14–16 across societies and cultures.15 Men who are violent towards their wives are more likely to have attitudes accepting violence and are more likely to approve of marital violence.17 Additionally, men who are violent, in general, are more likely to have positive attitudes towards violence against women.18,19 Given that attitudes towards IPV are an established predictor of IPV perpetration, the present study expands upon this by examining whether these attitudes interact with other known risk factors for IPV, namely, conflict resolution and exposure to violence, to increase the risk of IPV perpetration by young adult African American men. Previous research has indicated that African American women are at higher risk for experiencing IPV.20 More recent research suggests that once socioeconomic status and other known risk factors are considered, the relative risk of socioeconomic status (SES) on IPV varies by ethnicity, wherein compared to white or Hispanic couples, African American couples residing in impoverished neighborhoods were more likely to report IPV regardless of other factors like male or female perpetration of partner violence.21 Considering that the relative association of SES on IPV is especially influential among Black couples, it is pertinent to examine other factors that may be associated with an increased risk for IPV among African American women and their male partners.

Several studies have established a relationship between an individual’s level of skill in conflict resolution or problem solving and violence perpetration,22–25 and previous research has found that ineffective or destructive communication styles are more indicative of men who use violence.26,27 However, another important factor to consider beyond the individual is a couple’s pattern of conflict resolution or the extent to which the relationship involves a pattern of ineffective communication.28–30 Prior research has evidenced an association between couples’ perception of ineffective conflict resolution communication within their relationship and adverse couple functioning, including marital dissatisfaction and divorce,29,30 and IPV.27 Feldman and Ridley27 employed the Communication Patterns Questionnaire,31 a self-report measure assessing the perceptions partners have regarding their communication patterns during conflict. Compared to nonviolent men, men reporting IPV also described the communication pattern in their relationship as having less constructive communication and instead used more mutual blame, mutual threat, and mutual verbal aggression. The frustration of being unable to effectively resolve a conflict or assertively communicate within a relationship can lead to anger, which, in turn, may also lead to violence,14,26,32,33 and having attitudes that support males’ use of violence toward a female partner may increase this risk of violence.

Numerous studies have also observed a significant association between IPV and community-level factors, including exposure to neighborhood violence and poverty.21,34,35 It is believed that communities where violence exists lack cohesion and that repeated witnessing of community violence may make interpersonal violence, including IPV, a credible tool for negotiation.36,37 Gelles’38 social structural theory posits that IPV is a conditioned response to “socially structured stress,” or stress attributed to social conditions such as low income and education, poverty, and unemployment. The inequity within socioeconomic positions are experienced by the marginalized as stressors that may increase their risk of violence. Using this theory, one study found that as the proportion of the unemployed, the working class, and those living below the poverty level increased and the number of high school graduates within a neighborhood decreased, the rate of IPV increased.35 Hence, it is possible that attitudes towards IPV interact with exposure to neighborhood violence to increase men’s actual threat and use of violence towards their female partners.

Given that attitudes towards IPV is an independent, individual-level predictor of IPV, this study extends upon previous findings by examining two higher level predictors—perceived couple conflict resolution and exposure to neighborhood violence—as moderators of the association between African American men’s attitudes towards IPV and their perpetration of IPV. We hypothesize that higher perceptions of ineffective couple conflict resolution and greater exposure to neighborhood violence will interact with attitudes supporting IPV to elevate the risk of perpetrating IPV in the past 3 months. The interplay of these factors and their role on IPV have important implications for violence prevention programs for both men and women.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This study is part of a larger study targeting African American men for an HIV/STI intervention piloted from March 2009 through September 2009. Participants were recruited from barber shops and recreational facilities frequented by African American men throughout the metropolitan area of Atlanta. Those males self-identifying as African American, heterosexual, unmarried, between the ages of 18 and 29 years, and reporting unprotected vaginal intercourse within the last 30 days were eligible to participate in the larger study. Overall, 96 of 113 African American men met the eligibility criteria, and of those eligible, 80 men agreed to participate, yielding a response rate of 83 %. Considering this study assessed perceived couple conflict resolution, only men reporting a main relationship (n = 65) were included in the study analyses. Men agreed to complete an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) assessing several demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors. The study protocol was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board prior to implementation. Participants provided informed consent, and each participant was compensated for his completion of these study procedures.

Measures

Sociodemographics

Participants were asked to report their age in years, highest level of education obtained, and whether they or someone living in their household received public assistance (i.e., welfare, TANF, SSI, food stamps, WIC, or section 8 housing subsidies). Additionally, participants reported the length (in months) of their main relationship and whether they lived with their “girlfriend.”

Attitudes Towards Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Attitudes towards IPV were assessed using a 12-item, Likert-type scale39 (α = .80) that measures men’s attitudes towards males’ use of violence against a dating partner. Response options ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Negatively worded items were reverse-scored, all items were summed, and higher scores represented greater acceptance of violent behavior towards female partners.

Ineffective Arguing Inventory (IAI)28

A revised version of the IAI assessed perceived couple conflict resolution. As opposed to assessing an individual’s style of resolving conflict, this six-item, Likert-type scale (α = .75) measured men’s perception of how they and their partner resolve conflict as a couple. Example items include, “By the end of an argument, you and your partner have really listened to each other,” “You and your partner’s arguments are left hanging and unsettled,” and “You and your partner go for days being mad at each other.” Response options ranged from (1) strongly agree to (5) strongly disagree. Positively worded items were reverse scored; all items were summed, and higher scores indicated a higher degree of perceived ineffective conflict resolution between the participant and his partner.

City Stress Inventory (CSI)40

A shortened version of the CSI assessed neighborhood disorder and men’s exposure to neighborhood violence. Men were asked to report the frequency in which several events (e.g., gang, drug, gun activity, and public disputes) occurred in their neighborhood during the past year. Response options ranged from never (1) to often (4), all scores were summed, and higher scores on this 11-item survey (α = .91) indicated greater exposure to neighborhood violence.

Abusive Behavior Inventory (ABI)41

A revised version of the ABI assessed recent IPV perpetration Participants indicated on a five-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently) how often in the past 3 months they engaged in various physically (e.g., threatened her with a knife, gun, or other weapon), emotionally (e.g., made her do something humiliating or degrading like beg for forgiveness), or sexually (e.g., physically forced her to have oral, anal, and/or vaginal sex) abusive behaviors towards a dating partner (24 items; α = .82). All scores were summed, and higher scores indicate higher frequency of IPV perpetration.

Data Analysis Plan

This study tested two models predicting IPV perpetration: the interaction of attitudes supporting IPV with (1) perceived ineffective couple conflict resolution and (2) neighborhood violence. Separate hierarchical linear multiple regression analyses tested each model. Based on previous research on IPV perpetration,42,43 demographics (age, education, and public assistance) and relationship characteristics (cohabitation and relationship length) were entered as covariates in the first and second steps of each model. The predictor variable (attitudes supporting IPV) was entered into the second step, and each moderator variable (ineffective couple conflict resolution communication and neighborhood violence) was entered into the third step of its model. The interaction term was entered in the final step of each model. The two interaction terms were calculated by centering the predictor and moderator variables and then multiplying the centered predictor variable with each moderator variable. To aid in the graphing of significant interaction effects, we plotted the regression line between y (the criterion variable) and x (the predictor variable) at specific values of z (moderator variable). When entering one standard deviation below and above the mean of z, these points represented the lower and upper values associated with each of the slopes, respectively.44 Significance test for the slopes representing each model were also conducted.45

Results

Participants reported an average age of 23 years (SD = 3.5 years). More than a third of the sample (n = 24) reported receiving a high school diploma or GED as the highest level of education attained, while 17 % (n = 11) reported attending some college. Forty percent (n = 26) reported having a paying job, and half of those men reported earning $9 or less per hour (M = 9.82, SD = 3.38). Also, 55 % of men reported living in a household that received some form of public assistance. Relationship, psychosocial, and behavioral characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1. This sample reported varying lengths of time in their current relationships with 50 % reporting having been in their current relationship for 19 months or longer. Forty-two percent of men (n = 27) indicated they were cohabitating with their current partner.

Table 1.

Relationship, psychosocial, and behavioral characteristics of 65 heterosexual African American men, aged 18–29, Atlanta, GA, 2009

| Attitudes and behaviors | Number (%) | Range for scale/self-report | Cronbach’s α | M | (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship length | 1–159 | 33.98 | 35.15 | ||

| Lives with main partner | 27 (42) | ||||

| Has children | 40 (62) | ||||

| Children live with participant | 29 (45) | ||||

| Attitudes supporting IPV | 12–60 | .80 | 23.84 | 8.76 | |

| Ineffective couple conflict resolution communication | 6–30 | .75 | 15.16 | 5.39 | |

| Exposure to neighborhood violence | 11–44 | .91 | 26.25 | 9.05 | |

| IPV perpetration (past 3 months) | 24–120 | .82 | 31.13 | 5.33 |

Model 1

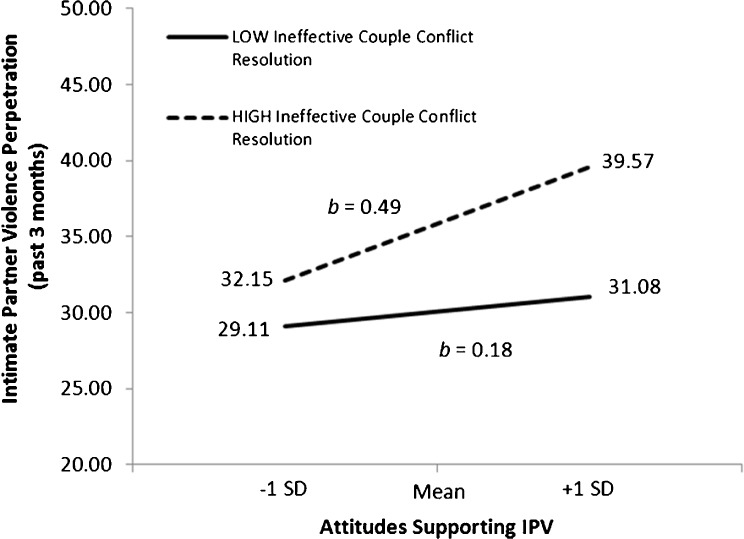

When controlling for demographics and relationship characteristics, there was a significant interaction effect of attitudes supporting IPV and perceived ineffective couple conflict resolution on males’ recent perpetration of IPV, Adjusted R2 = .151, ∆F(1,56) = 4.52, p = .04 (Table 2). The association between attitudes supporting IPV and IPV perpetration was greater among men reporting high ineffective couple conflict resolution than among men reporting low ineffective couple conflict resolution (Figure 1). Among men reporting low ineffective couple conflict resolution, IPV perpetration increased 0.18 U for each unit increase in attitudes supporting IPV, t(56) = 1.65, n.s., whereas among men reporting high ineffective couple conflict resolution, IPV perpetration increased 0.49 U for each unit increase in attitudes supporting IPV, t(56) = 4.60, p < .001.

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear regression of interaction effect of perceived ineffective couple conflict resolution and attitudes supportive of IPV on male perpetration of IPV in the past 3 months, Atlanta, GA, 2009

| Predictor variable | Adjusted R2a | ∆R2 | ∆F | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Age | .019 | 0.065 | 1.41 | −1.50 | .25 |

| Education | 0.446 | ||||

| Public assistance | −2.51 | ||||

| Step 2: Cohabitation | .037 | 0.048 | 1.59 | −2.07 | .21 |

| Relationship length | 0.014 | ||||

| Step 3: Attitudes supporting IPV | .044 | 0.021 | 1.38 | 0.066 | .24 |

| Step 4: Ineffective couple conflict resolution communication | .098 | 0.063 | 4.50 | 0.336 | .04 |

| Step 5: Interaction term | .151 | 0.060 | 4.52 | 0.030 | .04 |

aAdjusted for demographics (age, education, and public assistance) and relationship characteristics (cohabitation and relationship length)

Figure 1.

Regression lines for association between attitudes supporting IPV and male perpetration of IPV in the past 3 months, as moderated by perceived ineffective couple conflict resolution (a two-way interaction). b unstandardized regression coefficient (i.e., simple slope), SD standard deviation.

Model 2

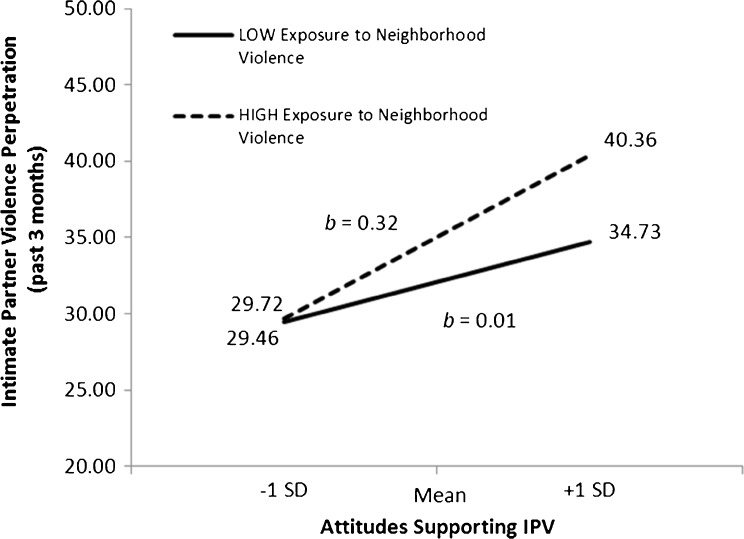

When controlling for demographics and relationship characteristics, there was a significant interaction effect of attitudes supporting IPV and neighborhood violence on males’ recent perpetration of IPV, Adjusted R2 = .221, ∆F(1,56) = 6.00, p = .02 (Table 3). The association between attitudes supporting IPV and IPV perpetration was greater among men with high exposure to neighborhood violence than among men with low exposure to neighborhood violence (Figure 2). Among men with low exposure to neighborhood violence, IPV perpetration increased 0.01 U for each unit increase in attitudes supporting IPV, t(56) = 0.15, n.s., whereas among men with high exposure to neighborhood violence, IPV perpetration increased 0.32 U for each unit increase in neighborhood violence, t(56) = 3.30, p < .001.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear regression of interaction effect of exposure to neighborhood violence and attitudes supportive of IPV on male perpetration of IPV in the past 3 months, Atlanta, GA, 2009

| Predictor variable | Adjusted R2a | ∆R2 | ∆F | B | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Age | .019 | 0.065 | 1.41 | −0.264 | .25 |

| Education | 0.706 | ||||

| Public assistance | −1.86 | ||||

| Step 2: Cohabitation | .037 | 0.048 | 1.59 | −2.04 | .21 |

| Relationship length | 0.033 | ||||

| Step 3: Attitudes supporting IPV | .044 | 0.021 | 1.38 | 0.085 | .24 |

| Step 4: Exposure to neighborhood violence | .152 | 0.112 | 8.44 | 0.168 | .01 |

| Step 5: Interaction term | .221 | 0.073 | 6.00 | 0.017 | .02 |

aAdjusted for demographics (age, education, and public assistance) and relationship characteristics (cohabitation and relationship length)

Figure 2.

Regression lines for association between attitudes supporting IPV and male perpetration of IPV in the past 3 months, as moderated by exposure to neighborhood violence (a two-way interaction). b unstandardized regression coefficient (i.e., simple slope), SD standard deviation.

Discussion

Family violence research suggests that the occurrence of violence between intimate partners is multifaceted, involving multiple risk factors beyond individual-level predictors.27 This study assessed the interaction of an individual-, interpersonal-, and community-level predictor of IPV perpetration among an economically disadvantaged sample of African American men. As expected, attitudes supporting IPV were positively related to IPV perpetration, and ineffective couple conflict resolution communication and exposure to neighborhood violence moderated the relationship between this individual-level factor and perpetration by elevating the risk of male perpetration of IPV.

The finding that exposure to neighborhood violence was associated with an increase in recent male perpetration of IPV is consistent with previous studies34,46,47 and supports the notion that “the environmental context influences what goes on in the privacy of homes.”46, p. 396 One study34 argued that the effect of community violence on male violence toward a female partner could be explicated by a lack of strong connections between community residents and hence, little collective efficacy to control the level of violence in their disordered neighborhoods. A higher threshold for violence in a community can also normalize the use of violence and provide opportunities to consort with others that support the use of violence, thereby producing violent male networks that increase individual risk for perpetration.34 In the present study, IPV perpetration increased as a function of both attitudes supporting IPV and high exposure to community violence. Considering the environmental context in which violence is enacted and observed, prevention of IPV perpetration and victimization must involve coordinated efforts at the community level, in addition to the individual and family levels.

Given that intimate relationships between men and women are characterized as interdependent, often experiencing competing goals and resource constraints, conflict in relationships is expected. However, ineffective conflict resolution is associated with destructive outcomes like IPV.48,49 Whereas previous IPV research26,27 has focused on conflict resolution at the individual level (i.e., targeting an individual’s ability to resolve conflict), this study assessed the issue of conflict resolution at an interpersonal level—an individual’s perception of how he and his partner resolve conflict. This study’s findings suggest that males’ perceptions of ineffective conflict resolution elevate the risk of IPV perpetration, given attitudes supporting IPV also exist. As Feldman and Ridley’s27 study indicated, relationships are often mutually combative, especially in the African American community where rates of male to female partner violence (MFPV) and female to male partner violence (FMPV) are two to 2.7 times as high as the rates among Whites.50 However, caution is needed in the implication and application of these findings as male and female use of aggression and violence cannot be treated equally. Furthermore, such findings do not imply there is less power imbalance in African American couples relative to other groups, and other contributing factors may exist.

IPV and community violence may be understood as mechanisms for resolving conflict when other methods for resolving conflict due to competing demands are not available or successful.27 Many IPV studies focus on individual-level variables like attitudes or individual conflict resolution skills without considering higher level factors like exposure to violence in the community and the ways in which a couple, not an individual, resolve conflict. This focus has driven IPV prevention interventions for men to exclude prevention partners or community members and organizations. In their review of primary and secondary dating violence prevention programs, Cornelius and Resseguie22 found that most interventions focus on education, gender role attitudes, attitudes towards violence, and psychoeducational resources for perpetrators and victims. However, the facilitation of behavior change requires that men and women also learn skills for effective communication, negotiation, conflict resolution, and anger management through modeling, role playing, and rehearsal of skills.22,27,46

In addition to skill building and couples-level interventions, Gelles’38 social structural theory, which focuses on social stressors and poor social conditions, indicates that attention is needed towards structural factors that promote IPV. Structural interventions offer an opportunity to target social determinants of health in multiple capacities.51 These interventions might include job training, debt relief counseling, and income generation.52 A microfinance-based structural intervention in South Africa was found to be effective in reducing IPV over a 2-year period.53 Community- and societal-level interventions should alter norms surrounding neighborhood violence, conflict resolution skills, and IPV. If men participate in individual-level IPV interventions but then return to communities where violence or norms that support violence exist, then this may lead them to revert back to old behaviors, including IPV perpetration.34

Limitations

Despite significant and interesting findings associated with African American men’s perpetration of IPV, it is necessary to discuss potential limitations of this study. Given the cross-sectional analyses, causal interpretations cannot be made. Also, the data on IPV attitudes, perceptions of conflict resolution, and perpetration of and exposure to violence rely on retrospective self-report data. It is possible that participants had difficulty recalling important information and/or they provided a socially desirable response to sensitive questions. However, use of the ACASI can reduce socially desirable responses and increase the likelihood of more honest responding.54,55 Also, other sources of data for couples’ pattern of conflict resolution (e.g., partner’s perception and actual observations of couple conflict resolution) would be superior to one partner’s perception of couple conflict resolution. Given the small sample size, it is possible that we may have failed to detect other associations among the study variables due to insufficient power. However, the inclusion of other known predictors of IPV perpetration not assessed in the current study (e.g., peer norms, family violence, stress, witnessing and experiencing violence as a child, and antisocial personality characteristics) might have increased the magnitude of the models’ effect. Finally, the results of this study may have limited generalizability to men from other racial/ethnic backgrounds or men from various geographic regions of the United States other than the southeast. Given that the eligibility criteria for the larger study included engaging in risky sexual behavior, replication with diverse populations is ideal.

Conclusions

Interventions for IPV are essential, as IPV serves as a risk factor for other negative health behaviors. Considering the increased risk of physical, psychological, and sexual health concerns in the context of partner violence,2,5–7,56,57 prevention interventions targeting key risk factors are essential. For example, the number of studies assessing prevention interventions that address both IPV and sexual risk is scant.11 Although numerous dating violence prevention programs have been developed, most are not evaluated for their effect on changes in attitudes and behaviors.22 Furthermore, the majority of dating violence prevention programs target individuals within school systems (e.g., adolescents and college-aged men and women), and the efficacy of these interventions has not been evaluated with older men and women. Future research should assess IPV-related factors that may differ for older samples of intimate partners and design prevention programs to meet the needs of these individuals.22

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control;2003.

- 2.Seth P, Raiford JL, Robinson L, Wingood GM. Intimate partner violence and other partner-related factors: correlates of sexually transmissible infections and risky sexual behaviours among young adult African American women. Sex Heal. 2010;7:25–30. doi: 10.1071/SH08075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raiford JL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. Effects of fear of abuse and possible STI acquisition on the sexual behavior of African American adolescent girls and young women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1067–1071. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Definition of intimate partner violence. 2009; http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/intimatepartnerviolence/definitions.html. Accessed March 17, 2009.

- 5.Edwards V, Black M, Dhingra S, McKnight-Eily L, Perry G. Physical and sexual intimate partner violence and reported serious psychological distress in the 2007 BRFSS. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;54:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hien D, Ruglass L. Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: an overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2009;32:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell R, Lichty LF, Sturza M, Raja S. Gynecological health impact of sexual assault. Res Nurs Heal. 2006;29:399–413. doi: 10.1002/nur.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley R, Schwartz AC, Kaslow NJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among low-income African-American women with a history of intimate partner violence and suicidal behaviors: self-esteem, social support, and religious coping. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:685–696. doi: 10.1002/jts.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu E, El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Chang M. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk among urban minority women in primary health care settings. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(3):291–301. doi: 10.1023/A:1025447820399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer HM, Gibson P, Hernandez M, Kent C, Klausner J, Bolan G. Intimate partner violence and high-risk sexual behaviors among female patients with sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(7):411–416. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American deep south. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(4):701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2003.

- 14.Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: a meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10:65–98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawoko S. Predictors of attitudes toward intimate partner violence: a comparative study of men in Zambia and Kenya. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1056–1074. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6(1):46–61. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.6.1.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders DG, Lynch AB, Grayson M, Linz D. The inventory of beliefs about wife beating: the construction and initial validation of a measure of beliefs and attitudes. Violence and Victims. 1987;2:39–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shields NM, McCall GJ, Hanneke CR. Patters of family and nonfamily violence: violent husbands and violent men. Violence and Victims. 1988;3:83–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadsky O, Crawford M. Establishing batterer typologies in a clinical sample of men who assault their female partners. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1988;7:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Schafer J, Clark CL. Intimate partner violence and drinking among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the US. J Subst Abus. 2000;11:123–138. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark CL, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: Multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornelius TL, Resseguie N. Primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: a review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007;12:364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2006.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riggs D, O’Leary K, Breslin F. Multiple correlates of physical aggression in dating couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1990;5:61–73. doi: 10.1177/088626090005001005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riggs D, O’Leary K. A theoretical model of courtship aggression. In: Pirog-Good MA, Stets JE, editors. Violence in dating relationships. New York: Praeger; 1989. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonio T, Hokoda A. Gender variations in dating violence and positive conflict resolution among Mexican adolescents. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:533–545. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson K, Murachver T. Attitudes and attributions associated with female and male partner violence. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;39:1481–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00492.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman CM, Ridley CA. The role of conflict-based communication responses and outcomes in male domestic violence toward female partners. J Soc Pers Relat. 2000;17:552–573. doi: 10.1177/0265407500174005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurdek LA. Conflict resolution styles in gay, lesbian, heterosexual nonparent, and heterosexual parent couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:705–722. doi: 10.2307/352880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottman JM, Krokoff LJ. Marital interaction and satisfaction: a longitudinal view. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:47–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder DK. Manual for the marital satisfaction inventory.: Western Psychological Services; 1981.

- 31.Christensen A. Dysfunctional interaction patterns in couples. In: Knoller P, Fitzpatrick MA, editors. Perspectives on marital interaction. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters; 1988. pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toro-Alfonso J, Rodriguez-Madera S. Domestic violence in Puerto Rican gay male couples: perceived prevalence, intergenerational violence, addictive behaviors, and conflict resolution skills. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:639–654. doi: 10.1177/0886260504263873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norlander B, Eckhardt C. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:119–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghavan C, Rajah V, Gentile K, Collado L, Kavanagh AM. Community violence, social support networks, ethnic group differences, and male perpetration of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:1615–1632. doi: 10.1177/0886260509331489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Harris TR. Neighborhood characteristics as predictors of male to female and female to male partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Goldstein PJ. The drug/violence nexus: a tripartite conceptual framework. Journal of Drug Issues. 1985;15:493–506. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross CE, Jang SJ. Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:401–420. doi: 10.1023/A:1005137713332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gelles RJ. Family violence. Annu Rev Sociol. 1985;11:347–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.11.080185.002023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price EL, Byers ES. The attitudes towards dating violence scales: development and initial validation. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14(4):351–375. doi: 10.1023/A:1022830114772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: development and validation of a neighborhood stress index. Heal Psychol. 2002;21(3):254–262. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shepard MF, Campbell JA. The abusive behavior inventory: a measure of psychological and physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7:291–305. doi: 10.1177/088626092007003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raj A, Santana C, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1873–1878. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Kapur NA, Gupta J, Raj A. Violence against wives, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection among Bangladeshi men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(3):211–215. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(1):87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stueve A, O’Donnell L. Urban young women’s experiences of discrimination and community violence and intimate partner violence. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:386–401. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghavan C, Mennerich A, Sexton E, James S. Community violence and its direct, indirect, and mediating effects on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1–18. doi: 10.1177/1077801206294115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messinger AM, Davidson LL, Rickert VI. IPV among adolescent reproductive health patients: the role of relationship communication. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(9):1851–1867. doi: 10.1177/0886260510372933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bell KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: moving towards a contextual framework. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(7):1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casenave NA, Straus MA. Race, class network embeddedness, and family violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, eds. Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990:321–335.

- 51.Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Higgins JA. Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):435–445. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1996;60:275–304. doi: 10.1086/297751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wingood GM, Seth P, DiClemente RJ, Robinson LS. Association of sexual abuse with incident high-risk human papillomavirus infection among young African American women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:784–786. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b3567e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]