Abstract

A clear understanding of local transmission dynamics is a prerequisite for the design and implementation of successful HIV prevention programs. There is a tremendous need for such programs geared towards young African-American women living in American cities with syndemic HIV and injection drug use. In some of these American cities, including Baltimore, the HIV prevalence rate among young African-American women is comparable to that in some African nations. High-risk heterosexual sex, i.e., sex with an injection drug user or sex with someone known to have HIV, is the leading risk factor for these young women. Characterizing transmission dynamics among heterosexuals has been hampered by difficulty in identifying HIV cases in these settings. The case identification method described in this paper was designed to address challenges encountered by previous researchers, was based on the Priorities for Local AIDS Cases methodology, and was intended to identify a high number of HIV cases rather than achieve a representative sample (Weir et al., Sex Transm Infect 80(Suppl 2):ii63-8, 2004. Through a three-phase process, 87 venues characterized as heterosexual sex partner meeting sites were selected for participant recruitment in Baltimore, MD. One thousand six hundred forty-one participants were then recruited at these 87 venues, administered a behavioral risk questionnaire, and tested for HIV. The HIV prevalence was 3 % overall, 3 % among males, and 4 % among females and ranged from 1.7 to 22.6 % among high-HIV-risk subgroups. These findings indicate that attributing HIV transmission to high-risk heterosexual sex vs. other high-HIV-risk behaviors would be difficult. Moving beyond individual risk profiles to characterize the risk profile of venues visited by heterosexuals at high risk of HIV acquisition may reveal targets for HIV transmission prevention and should be the focus of future investigations.

Keywords: HIV, Heterosexual, Prevalence, Disease transmission, Infectious, Drug user, Adult

Introduction

African-American women in Baltimore City and five other US cities are becoming infected with HIV at a rate five times the national average for African-American women, close to rates observed in some African countries.2 Among American women 13 to 24 years old, heterosexual contact remains the primary mode of infection, responsible for 90 % of all infections in 2009.3 The local source of the infection for these women and the role of parenteral transmission routes such as injection drug use (IDU) and needle sharing are unknown.4–6 Also unclear is the extent to which these heterosexually transmitted infections may be resulting in other heterosexual infections among men who are otherwise at lower risk, i.e., heterosexual, non-IDU. A clear understanding of HIV transmission dynamics is necessary to design and implement successful prevention strategies in order to reduce infection among heterosexuals particularly among young, African-American women.

In Baltimore, as in other areas, it has been difficult to identify heterosexually infected individuals. Household studies have failed to identify large numbers of HIV-infected individuals with HIV prevalence reported to be less than 1 % in these study populations.7 Clinic-based studies have also yielded low numbers of heterosexual cases. For example, in 2009, among 15- to 24-year-old public STD clinic clients who self-identified as heterosexual, there were a total of eight HIV cases among males and four cases among females resulting in HIV prevalence in both genders of less than 1 % (unpublished data). Given the lack of HIV cases identified in these settings, we used the Priorities for Local AIDS Cases methodology in this study to identify high-HIV-risk community venues, which were reported as heterosexual sex partner meeting venues.1 Other studies such as National Health Behavioral Surveillance Survey (NHBS) and the HIV Prevention Trials Network have also used a venue-based approach to conduct heterosexual HIV surveillance.

Our objectives for this study were to determine HIV prevalence overall, among males and females separately, and within specific behaviorally defined subgroups of heterosexual adults in a venue-based sample in order to characterize likely sources of HIV infection in this particular urban setting.8,9 We also sought to identify recent risk behaviors that were associated with HIV infection status and might be indicative of the ongoing transmission of HIV from infected to those susceptible to infection.

Methods

Study Setting

The setting for the current study presents a unique opportunity to address the study objectives. The study was conducted in Baltimore, a city with longstanding syndemics of poverty, illicit drug use, and HIV.9–11 Baltimore is located in the Mid-Atlantic USA with an estimated population in 2009 of 637,418 people.12 Baltimore has a 24 % poverty rate, nearly double that of the national rate, ranking it as the sixth poorest metropolitan area.12 Thirty-five percent of Baltimore's children live below the poverty line, compared to just 11 % statewide and 18 % nationally.12 Baltimore has high rates of IDU and non-IDU drug use.13–15 Baltimore is estimated to have at least 60,000 illicit drug addicts—roughly 10 % of the population—and police report that drugs are a factor in eight of every ten city homicides.16 It is estimated that about 40,000 of the city's estimated 60,000 addicts are IDUs with heroin featuring prominently.17,18 Baltimore also has endemic rates of STIs and is a city with racial/ethnic disparities in STIs that are four times the national average. In 2009, Baltimore had the fourth highest HIV incidence rate in the nation.19

Procedures

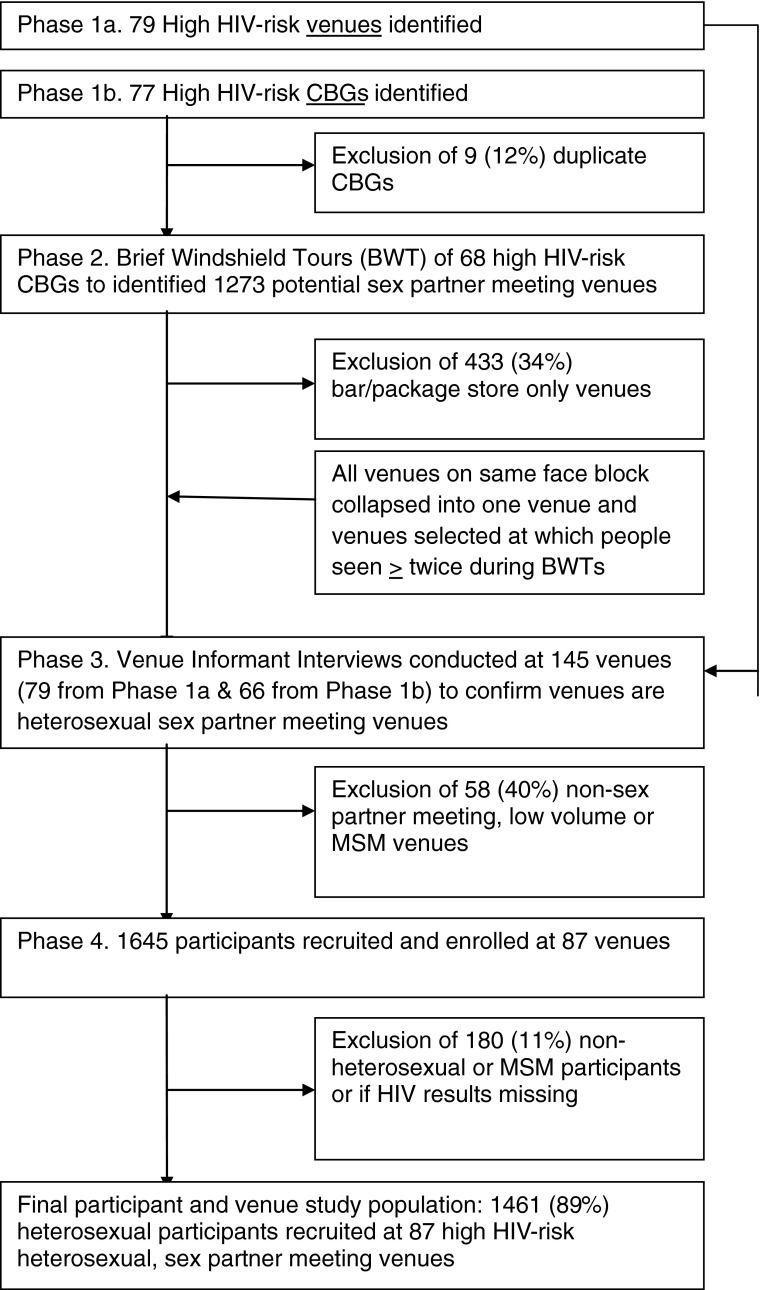

The study was a venue-based, cross-sectional study of adults 18 to 35 years of age conducted in Baltimore, MD from October 2008 through December 2009. Potential high-HIV-risk sex partner meeting venues were identified using a three-phase methodology (Figure 1).1 In phase 1, multiple sources of information were used to identify specific sex partner meeting venues and high-HIV-risk areas (i.e., census block groups (CBGs)) where sex partner meeting venues might exist. Sources of information that might yield drug-related venues were included. In phase 2, brief windshield tours (BWTs) were conducted in order to identify venues where “significant” numbers of people congregated. In phase 3, observational data were collected and venue informant interviews were conducted to identify high volume, heterosexual sex partner meeting sites, regardless of drug-related activity.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram for a venue-based study among 18–35-year-olds in Baltimore, MD, from 2008 to 2009.

Venue Selection

In phase 1 (a), primary data were collected from 309 public health STI clinic records from 2003 to 2004 and 2006, interviews with 26 key informants likely to be knowledgeable about commercial sex workers (CSWs) or IDU, and a 2008 on-line strip club directory to generate a list of potential venues. In phase 1 (b), secondary data analysis was used to identify high-HIV-risk CBGs as characterized by: (1) high (>92nd percentile) gonorrhea rates from 2002 to 2004 (n = 30); (2) high (>95th percentile) violent crime counts and high (>97.5th percentile) property crime counts from 2004 to 2005; (3) high drug prevalence (n = 10) (defined as top ten factor scores based on a factor analysis of average count of narcotics-related 911 calls from 1998 to 2001 and average count of juvenile drug arrests from 1998 to 2003); or (4) high (>95th percentile) heroin-related overdose fatality counts (n = 7) from 2004 to 2006. Identification through any single method described previously was adequate for further consideration of the venue for inclusion. De-duplication of 77 CBGs yielded 68 unique CBGs, representing 9.6 % (68/710) of CBGs in Baltimore.

In phase 2, three BWTs of each venue and high-HIV-risk CBG were conducted.20 A BWT consisted of a 3-h driving tour of each venue/area in order to record the locations and times of gatherings of three or more seemingly age-eligible adults, exclusive of bus stops, bars, and package stores. If people were observed to congregate at a venue on more than one occasion, it proceeded to phase 3 for further consideration.

In phase 3 at each venue, staff again assessed the number of people congregating and/or passing by and then interviewed three venue informants, i.e., patrons, passersby, or business owners. Based on these data, a venue was included if one or more venue informants reported it to be a sex partner meeting site. Venues were excluded if (1) all venue informants said no people met sex partners there; or (2) no venue informant said sex partners met there and the staff observed less than three people and all venue informants reported less than six people gathered at the venue at any time; or (3) staff reported the venue to be predominantly a meeting place for men who have sex with men (MSM). Venues meeting neither exclusion nor inclusion criteria were eligible for inclusion as part of a random sample, i.e., venues where venue informants answered “don't know” or “no” as to whether people met sex partners there and either: (1) greater than three people were observed by the staff, or (2) three venue informants reported at least six people would gather there at any time were eligible for inclusion as part of a random sample. A venue became a site for participant recruitment if it met inclusion criteria or was selected in a 66 % random sample. All venues at which participants were subsequently recruited fulfilled these venue selection criteria regardless of how they were originally identified in phases 1 and 2.

Participant Recruitment and Interview Procedures

Operating from a modified recreational vehicle, a team of three staff members recruited and enrolled participants at the selected venues between 6 and 9 p.m. on consecutive nights until 20 participants had been recruited. Staff recruited anyone who stepped into the area of sidewalk adjacent and equal in length to the van. Eligibility criteria were that participants be 18 to 35 years of age, English-speaking, and sexually active within the last 3 months. Eligible and interested participants provided informed consent, completed a brief, staff-administered questionnaire and were tested for HIV (OraSure). Participants received $20 for their time. HIV-positive participants were reported to the Maryland State AIDS Administration and the Baltimore Health Department for linkage to care. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participant Measures

HIV Infection

Participants were classified as HIV infected if the OraSure test and confirmatory western blot were both positive.

Sexual Orientation

Participants were asked whether they were heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual. Additionally, both male and female participants were asked if they had ever had sex with a man.

Demographics

Age, gender, and race/ethnicity (Black, White, Asian, Hispanic, or other) were self-reported by the participant and recoded to Black, White, and Other. Educational attainment was self-reported as the highest level of schooling completed (less than high school, some high school, high school or general equivalency diploma (GED), some college, bachelor's degree, and graduate studies).

High-HIV-Risk Behaviors

Sex Partnering Risk Behaviors

Participants were asked if in the past 12 months they had had sex with an IDU or someone HIV positive. High-HIV-risk heterosexual sex was defined as sex with an IDU or HIV-positive partner in the past 12 months.

CSW Risk Behaviors

Participants were asked whether in the past 12 months they had exchanged drugs or money for sex or whether they had exchanged sex for money or drugs. Participants answering either question positively were considered to be have engaged in CSW in the past 12 months.

Parenteral or IDU Risk Behaviors

Participants were asked whether they had used a needle to inject drugs ever in their lifetime and in the past 6 months. They were also asked whether they shared a needle while injecting drugs in the past 6 months. Participants were classified as IDU ever if they responded that they had used a needle to inject drugs any time in their lifetime. Participants were classified as having parenteral risk in the past 6 months if they responded positively to using a needle to inject drugs or sharing a needle or syringe while injecting drugs in the past 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate associations between HIV status and participant characteristics including demographics and high-HIV-risk behaviors were determined using a t test, chi-square, or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression models determined the association between HIV status and behaviorally defined high-HIV-risk subgroups. In all analyses, we stratified by gender because we hypothesized, based on the literature, that HIV prevalence and transmission dynamics would differ for males and females.19,21 In multivariable modeling, we adjusted for age because we hypothesized that the likelihood of HIV infection and behavioral risk would increase with age. We also adjusted for the non-independent nature of the data, i.e., clustering of individuals within venues. All statistical procedures were performed using STATA (STATA Intercooled, version 11.0; STATA Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

We enrolled 1,641 participants from 87 venues. Participants were excluded due to missing interviews (n = 30) or missing HIV testing results (n = 14). Because of our interest in heterosexual HIV transmission, we excluded men who reported having sex exclusively with men (n = 136), yielding a final sample size of 1,461 (89 %). The final sample included 661 men and 800 women (Table 1). The majority of participants were Black and had earned a high school diploma or GED.

Table 1.

Demographics and high-HIV-risk behaviors by HIV status of 18–35-year-old heterosexuals in a venue-based study, Baltimore, MD, 2008–2009

| Overall, n = 1,461 | Males, n = 661 | Females, n = 800 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | HIV−, n = 641 | HIV+, n = 20 | HIV−, n = 641 | HIV+, n = 20 | HIV−, n = 768 | HIV+, n = 32 | |||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | |

| Age, years | 27.2 | 6.0 | 32.9 | 5.5 | <0.001 | 27.6 | 6.2 | 33.3 | 4.8 | 0.0001 | 26.9 | 5.9 | 32.8 | 5.9 | <.0001 |

| Race | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | ||||

| Black | 1,168 | 96.3 | 45 | 3.7 | 523 | 83.0 | 17 | 85.0 | 645 | 84.3 | 28 | 87.5 | |||

| White | 196 | 97.5 | 5 | 2.5 | 94 | 14.9 | 2 | 10.0 | 102 | 13.3 | 3 | 9.4 | |||

| Other | 31 | 93.9 | 2 | 6.1 | >0.05 | 13 | 2.1 | 1 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 18 | 2.4 | 1 | 3.1 | 0.8 |

| High school diploma or GED | 824 | 58.6 | 26 | 50.0 | >0.05 | 362 | 56.7 | 11 | 55.0 | 0.9 | 462 | 60.2 | 15 | 46.9 | 0.1 |

HIV Prevalence

Overall, 52 or 3.2 % of participants tested positive for HIV (Table 2). The HIV prevalence among males was 3.0 % and among females was 4.0 %. The HIV prevalence among specific behaviorally defined subgroups for males and females is provided in Table 2 (range 1.7–22.6 %). In multivariable analysis adjusted for age and venue clustering, the odds of being HIV infected are two times greater for a male reporting IDU ever than for a male not reporting IDU ever (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 2.17; 95 % confidence Interval (CI) 1.08, 4.36). Females in any behaviorally defined subgroup, high-HIV-risk heterosexual sex, CSW, parenteral risk in the past 6 months, or IDU ever had an increased odds of being HIV infected compared to females not belonging to any such subgroup. Reporting no high-HIV behavioral risk was significantly associated with a 74 % decrease in the odds of being HIV infected compared to individuals reporting any high-HIV behavioral risk.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of HIV according to HIV-risk category and HIV prevalence according to HIV-risk category among 18–35-year-old participants in a venue-based study conducted in Baltimore, MD from 2008 to 2009

| Males (n = 661) | Females (n = 800) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95 % CI | HIV prevalence | 95 % CI | AOR | 95 % CI | HIV prevalence | 95 % CI | |

| Overall | 3.0 | 1.7, 4.3 | 4.0 | 2.6, 5.3 | ||||

| No reported risk | 0.46 | 0.20, 1.06 | 1.7 | 0.5, 2.9 | 0.26 | 0.11, 0.62 | 2.1 | 1.0, 3.2 |

| High-HIV-risk heterosexual sexa, past 12 months | 0.98 | 0.24, 3.94 | 5.0 | −1.8, 11.8 | 4.59 | 1.83, 11.6 | 18.8 | 7.7, 29.8 |

| CSW, past 12 months | 1.46 | 0.48, 4.48 | 5.5 | 1.5, 9.4 | 4.96 | 2.17, 11.4 | 15.8 | 8.7, 23.0 |

| Parenteral risk, past 6 months | 1.67 | 0.64, 4.35 | 7.9 | 2.7, 13.2 | 6.48 | 2.94, 14.3 | 16.7 | 8.4, 24.9 |

| IDU, ever in lifetime | 2.17 | 1.08, 4.36 | 7.0 | 1.1, 13.0 | 4.15 | 1.88, 9.15 | 22.6 | 11.4, 33.9 |

aHigh-HIV-risk heterosexual sex = IDU or HIV-positive sex partner in the past 12 months

High-HIV-Risk Behaviors

HIV-infected heterosexual male and female participants were significantly (P < 0.01) older than uninfected males and females (27.6 vs. 33.3 years and 26.9 vs. 32.8 years, respectively). For males, there were not any significant differences between HIV-infected and uninfected males according to race/ethnicity or high-HIV-risk sexual behaviors including high-HIV-risk heterosexual sex and CSW behaviors. There were significant differences in parenteral risk behaviors between HIV-infected and uninfected men. A higher percentage of HIV-infected (vs. uninfected) men injected drugs in the past 6 months (25.0 vs. 10.3 %; P < 0.05), shared needles in the past 6 months (15.0 vs. 3.7; P = 0.01), and reported IDU ever (40.0 vs. 14.5; P < 0.01).

HIV-infected (vs. uninfected) females differed significantly in their reported high-HIV-risk sexual behaviors; a higher percentage of HIV-infected vs. uninfected females in the past 12 months had had sex with an IDU (25.0 vs. 4.6; P < 0.0001), sex with an HIV positive (6.3 vs. 1.2; P < 0.05), exchanged drugs or money for sex (43.8 vs. 7.9; P < 0.001), and exchanged sex for drugs or money (25.0 vs. 7.4; P < 0.001). HIV-infected (vs. uninfected) females were also significantly more likely to have parenteral risk behaviors. A higher percentage of HIV-infected (vs. uninfected) females injected drugs in the past 6 months (37.5 vs. 5.2; P < 0.001), shared needles in the past 6 months (15.6 vs. 2.0; P < 0.001) and reported IDU ever (40.6 vs. 8.5; P < 0.001). In multivariable analyses adjusting for age and venue clustering, risk behaviors among females significantly associated with HIV infection were any risky CSW behaviors in the past 6 months (AOR 1.19; 95 % CI 1.04, 1.36; P = 0.010) and any parenteral risk behaviors in the past 6 months (AOR 2.76; 95 % CI 1.02, 7.45; P = 0.045).

Discussion

The high prevalence of HIV infection overall and among subgroups is suggestive of a high burden of infection in this urban venue-based sample of heterosexual adults aged 18 to 35 years. The HIV prevalence was 3 % overall and ranged from 1.7 % among males reporting no high-HIV-risk behaviors to 22.6 % among females reporting IDU ever. The overall HIV prevalence of 3 % was similar to findings in comparable populations. The NHBS found a 3 % HIV prevalence among heterosexuals in Baltimore in 2007.5 NHBS-HET was a cross-sectional survey administered to heterosexual males and females aged 18–50 recruited in Baltimore during 2006–2007. The population sampled similar, i.e., a heterosexual population at increased of HIV infection, although IDU and IDU venues were purposefully excluded in the NHBS, but not in our study. The identification of heterosexual HIV-infected individuals in both studies is notable given our lack of ability to identify cases from other sources of information. The persistent burden of infection among this heterosexual high-risk population suggests that efforts need to be better targeted to address the transmission of HIV in this population.

In examining the prevalence of HIV among heterosexuals in this high-risk setting, we found that it may be difficult to isolate heterosexual sexual risk from other high-HIV-risk exposures. This corresponds to findings from other studies. IDU, sex partner IDU, and CSW were highly prevalent among the heterosexual participants at the Baltimore and Washington, DC sites of the NHBS-HET studies. In Baltimore, 12 % reported IDU in the past year and 19 % reported CSW behaviors.5 In Washington, DC, 14 and 7 % reported individual or sex partner IDU, respectively, in the past year and of those not reporting recent IDU, HIV-positive (vs. HIV negative) men were five times and women were eight times more likely to report ever-IDU.6 Given attempts to exclude IDU from NHBS-HET in order to focus on heterosexual HIV risk, these rates of IDU may underrepresent the rates in these communities, among otherwise similar individuals.

The HIV prevalence of 1.96 in participants reporting no high-HIV-risk behaviors may indicate that self-sustained heterosexual transmission is contributing to the very high overall HIV prevalence at these venues. Alternatively, these HIV-positive participants may be misclassified as being without risk behaviors: they may not have known or may not have wanted to disclose their own or their sex partner's risk behaviors. As the population identified in this study is not representative of the general heterosexual population in Baltimore, inferring that there is generalized heterosexual transmission would be premature.

There are limitations to the current study. As in the NHBS-HET, we were unable to distinguish recent vs. prevalent infection which limits our ability to determine the cause of HIV acquisition. Self-reported data on demographic and HIV-risk behaviors may be misreported due to social desirability, lack of knowledge, or poor recall. The stigma associated with both drug use and lack of knowledge of sex partners' risk behaviors may make drug exposure data particularly difficult to obtain using a survey which may result in misclassification. It is possible that MSM account for some of the high-HIV prevalence among females not reporting HIV risk factors as females were not asked whether any of their sex partners were MSM. Finally, as stated, the results may not be generalizable to all US cities, but only those with highly endemic HIV and IDU.

Our findings suggest close links between heterosexuals and members of other high-HIV-risk subgroups. The interconnectedness of IDU and high-risk heterosexual HIV risk would suggest that needle exchange and drug treatment may remain critical in the prevention of heterosexual HIV transmission.22–24 HIV infection cannot easily be attributed to a single risk factor in the event that an HIV-positive person reports more than on high-HIV-risk behavior. This prompts one to look beyond the individual risk profile, to individual's risk environment. Future studies should focus on venue-level factors associated with HIV transmission.25–27 This study highlights the importance of high-HIV-risk venues for the screening and treatment of HIV-positive individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the men and women who participated in this study and the staff who collected the data. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number R21HD052438) and National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant number KO1 DA022298-01A1) are gratefully acknowledged for their support.

Footnotes

The data in this study were presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, San Francisco, February 19, 2010.

References

- 1.Weir SS, Tate JE, Zhusupov B, Boerma JT. Where the action is: monitoring local trends in sexual behaviour. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(Suppl 2):ii63–ii68. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The HPTN 064 (ISIS study)—HIV incidence in women at risk for HIV: US. 2012.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance in adolescents and young adults. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/index.htm; Updated 2011–2012. Accessed July 6, 2012.

- 4.Denning P, DiNenno E. Communities in crisis: is there a generalized HIV epidemic in impoverished urban areas of the United States? 2010.

- 5.Towe VL, Sifakis F, Gindi RM, Sherman SG, Flynn C, Hauck H, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection and sexual risk behaviors among individuals having heterosexual sex in low income neighborhoods in Baltimore, MD: the BESURE study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(4):522–528. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bcde46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magnus M, Kuo I, Shelley K, Rawls A, Peterson J, Montanez L, et al. Risk factors driving the emergence of a generalized heterosexual HIV epidemic in Washington, District of Columbia networks at risk. AIDS. 2009;23(10):1277–1284. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b51da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings JM, Taylor R, Iannacchione VG, Rogers SM, Chung SE, Huettner, et al. The available pool of sex partners and risk for a current bacterial sexually transmitted infection. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(7):532–538. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson L. Baltimore's HIV/AIDS epidemic, a unique challenge. Poster exhibition: the XV International AIDS Conference: abstract no. MoPeE4266

- 9.Simon D, Burns E. The corner: a year in the life of an inner-city neighborhood. 1st ed. New York: Broadway; 1997. Accessed June 20, 2012.

- 10.Agar M, Reisinger H. Numbers and trends: heroin indicators and what they represent. Hum Organization. 1999;58:365–374. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleghorn AA, Jones TS, Doherty MC, Celentano DD, Vlahov D. Acquisition and use of needles and syringes by injecting drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199509000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Census Bureau. Census 2000, summary file 3 (SF 3). 2003. <http://www.geolytics.com/Default.asp>. Updated 2003. Accessed February 12.

- 13.Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Monterroso E, Brown D, Vlahov D. Correlates of HIV infection among young adult short-term injection drug users. AIDS. 2000;14(6):717–726. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200004140-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta SH, Galai N, Astemborski J, Celentano DD, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland (1988–2004) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(3):368–372. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243050.27580.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlahov D, Anthony JC, Munoz A, Margolick J, Nelson KE, Celentano DD, et al. The ALIVE study, a longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in intravenous drug users: description of methods and characteristics of participants. NIDA Res Monogr. 1991;109:75–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig T. Drugs worsen in city, U.S. says: traffic in cocaine, heroin, ecstasy assessed by DEA. Baltimore Sun. 2000.

- 17.Associated Press. Baltimore leads in ER cases tied to drugs. Baltimore Sun. 1998.

- 18.United States. National Drug Intelligence Center. Heroin in the northeast. 2003.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents, by sex and age group, 2008-37 states and 5 U.S. dependent areas. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/slides/Adolescents_6.pdf.

- 20.MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, Sullivan PS. Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behaviors of men who have sex with men—a national application of venue-based, time-space sampling. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):39–47. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV prevalence estimates—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(39):1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strathdee SA, Stockman JK. Epidemiology of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users: current trends and implications for interventions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlahov D, Robertson AM, Strathdee SA. Prevention of HIV infection among injection drug users in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S114–S121. doi: 10.1086/651482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metzger DS, Navaline H. HIV prevention among injection drug users: the need for integrated models. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4 Suppl 3):iii59–iii66. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gindi RM, Sifakis F, Sherman SG, Towe VL, Flynn C, Zenilman JM. The geography of heterosexual partnerships in Baltimore city adults. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(4):260–266. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f7d7f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohl DA, Khan MR, Tisdale C, Norcott K, Duncan J, Kaplan AM, et al. Locating the places people meet new sexual partners in a southern US city to inform HIV/STI prevention and testing efforts. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):283–291. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9746-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodhouse DE, Rothenberg RB, Potterat JJ, Darrow WW, Muth SQ, Klovdahl AS, et al. Mapping a social network of heterosexuals at high risk for HIV infection. AIDS. 1994;8(9):1331–1336. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]