Abstract

Walking outdoors is often difficult or impossible for many seniors and people with disabilities during winter. We present a novel approach for conducting winter accessibility evaluations of commonly used pedestrian facilities, including sidewalks, street crossings, curb ramps (curb cuts and dropped curbs), outdoor stairs and ramps, building and transit entrances, bus stops, and driveways. A total of 183 individuals, aged 18–85 completed our survey. The results show that cold weather itself had little impact on the frequency of outdoor excursions among middle-aged and older adults while the presence of snow and/or ice on the ground noticeably kept people, especially older adults at home. The survey found that the key elements decreasing winter accessibility were icy sidewalks and puddles at street crossings and curb ramps. While communities have recognized the need to improve snow and ice removal, little attention has been paid to curb ramp design which is especially ineffective in winter when the bottom of the ramps pool with rain, snow, and ice, making it hazardous and inaccessible to nearly all users. We conclude that investigations of alternative designs of curb ramp are needed.

Keywords: Winter, Accessibility, Pedestrian facilities, Participation, Physical activity

Introduction

The study of the effect of weather on pedestrian accessibility is limited and sometimes neglected.1,2 Several studies indicate that most outdoor falls occur on sidewalks, curbs, and streets,3 and the largest proportion of falls take place during the winter months.4 Icy surfaces are one of the most cited factors that lead to falls.5 Few studies have been done to investigate pedestrians’ perception of how the winter weather changes a normally accessible route to an inaccessible one. Several studies among adults report that poor weather is perceived as a barrier to physical activity6–10 and that daily physical activity levels decrease as ambient temperature drops and also decrease with rain and snowfall.11,12 People with functional limitations reported that curb ramps become particularly hazardous in winter.13–15 A prime indicator of the accessibility of an architectural environment is the degree to which the environment enables the performance of relevant activities by its users. An architectural environment that complies with the 7 Principles of Universal Design16 should enable comparable activity performance by all its users regardless of the users’ functional limitations in all weather conditions.

A growing body of research in public health pays attention to environmental factors as they correlate to physical activity, participation, and accessibility.17–19 There are numerous different scientific approaches to the study and measurement of environmental factors ranging from experimental manipulation of the environment in randomized controlled trials to questionnaires on subjective experiences of environmental barriers to participation.20 Questionnaires that ask people with disabilities about environmental barriers and facilitators are probably the instruments known best in the area of human functioning and disability research. When one asks for barriers or facilitators, the environment–functioning interaction is directly addressed. Several measures have been used to assess the influence of various environmental features on the participation of people with disabilities. However, only a few of the instruments included weather and climate as environmental factors and examined their influence on participation and accessibility, such as the Craig Hospital Inventory of Environmental Factors (CHIEF)21 and the Measure of the Quality of the Environment (MQE).22,23 The CHIEF measure revealed the most commonly identified barriers for both people with disabilities and those without disabilities; the number one barrier was weather.21 The MQE asked to what extent the winter climatic conditions (snow, ice, cold, etc.) or summer climatic conditions (heat, humidity, rain, etc.) as well as the sidewalk and intersection accessibility in the summer or winter influence people’s daily life.23 Boucher et al. used the MQE and found that intersection accessibility was rated as an obstacle in the winter but as a facilitator in the summer by most users.23 Therefore, it is important to identify built environment and natural features that cause the most problems for accessibility in winter conditions not only at intersections but also at other pedestrian facilities. The purpose of this study was to develop a questionnaire to gather information about different age groups, explore winter-related accessibility issues, assess the impact of adverse weather, assess the performance of pedestrian facilities, and identify facilities and features that need to be improved and enhanced as high priority needs.

Methods

Sampling Procedure

The purpose of sampling in this study was to make comparisons across three age groups: young (between 18 and 34 years), middle aged (between 35 and 59 years), and older (>60 years) as well as between people with and without functional limitations (mobility, hearing, and/or vision limitations). The goal of universal design is to address the needs of a wide variety of people. As such, people with specific functional limitations can be viewed as “reference users.” Meeting the needs of these reference users can effectively meet the needs of everyone else. The intent was to understand the priorities and what effectiveness means for people with functional limitations, not to generalize to the whole population.

The sample was a convenience sample and participants from diverse geographical and socio-economic contexts were recruited using a hybrid sampling method: (1) a survey invitation was sent to all employees of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (TRI); (2) an invitation letter was posted on an online daily news blog called Spacing Toronto; (3) an invitation flyer and a print version of the web survey was posted at five community centers across the City of Toronto to recruit community-dwelling older people. In all, 261 people responded to the survey over a 2-month period (March–April 2008). Of those who responded, 74 people were excluded because of a lack of response on the functional limitation and/or winter outdoor experience measures. Furthermore, four respondents were not included in the analysis since they lived outside the Greater Toronto Area (based on postal code). The total sample size analyzed was 183 of which 69 responses were obtained from the TRI site, 96 from Spacing Toronto, and 18 from the community centers.

Questionnaire Development

A web-based survey (print version was provided upon request) was used to identify priority needs for increased accessibility and usability of pedestrian facilities in the winter. Features causing the most problems that related to winter conditions were identified as high priority needs that became the focus of further study. The questionnaire study was approved by the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Research Ethics Board.

A literature review performed prior to this study failed to identify any previously tested instrument for assessment of perceived winter accessibility. As such, a new survey questionnaire had to be developed. The core part of the questionnaire concerning outdoor locations, perceived problems, and winter coping strategies were identified based on a qualitative study using observation and interview with six older people (60 years and older). A more traditional part of the questionnaire covered basic demographics as well as aspects of health (self-reporting of functional limitations) according to Steinfeld24and Danford et al..25 The questionnaire was developed over a period of 3 months and went through an iterative revision process. The final questionnaire comprised 31 structured questions and five open-ended questions. The questions were classified into three categories:

General information: This part contains questions on age group, gender, household income group, residential environment, and postal code. Participants were also asked to estimate the weekly frequency of outdoor excursions in a typical autumn week and in a winter week with or without snow/ice on the ground. These three conditions were chosen because they represent a relatively comfortable (autumn), a less comfortable (winter without snow/ice on the ground), and a difficult (winter with snow/ice on the ground) time to be outdoors in Toronto. Six response alternatives were given, ranging from 1 = “rarely” to 6 = “more than one time/day”.

Functional limitations: This part contains 11 questions on functional limitation measures. The initial concept of the functional limitation measures came from The Enabler, which is described in Steinfeld’s “Access to the Built Environment: A Review of the Literature”.24 The Enabler concept illustrated 15 different disability concerns that should be considered in design. Danford and his colleagues at University at Buffalo then developed a set of questions on sensory or functional conditions (e.g., limitations in mobility, vision, hearing, cognition, etc.) and how often each condition affects performance of routine activities.25 Then they hired 13 independent consultants with a variety of impairments to review and validate the functional limitation measures. The input received during this consultation has helped Maisel and her colleagues refine the questions and specifically made them change the language from “limitations” to “conditions” within the survey (Jordana Maisel, personal communication). Functional limitation was subjectively assessed in the questionnaire by asking the respondents how often various mobility, hearing, or sight conditions affect their ability to perform routine activities. The respondents were asked to rate the frequency on a three-point scale (1 = “always”, 2 = “sometimes” to 3 = “never”). The mobility, hearing, or sight condition could be due to a permanent circumstance or temporary injury or circumstance (e.g., a broken leg or pregnancy). A person is considered to have a functional limitation if he/she responded “always” or “sometimes” to any of the conditions. The respondents were asked to indicate one limitation which most affected their ability with the response alternatives “mobility”, “hearing”, and “sight”. Concerning reliance on assistive devices, the respondents were asked: “What assistance and/or assistive devices do you use outside in the winter?” The response alternatives were: “I do not use any assistive aids”, “cane/crutches”, “wheelchair”, “scooter”, and “hearing aid”, and it was possible for the respondents to report use of more than one assistive device or to fill in “other” devices not listed.

- Experiences in getting around outdoors in the winter and winter coping strategies: This is the core part of the questionnaire and was developed based on a qualitative study with six older people (60 years and older) who were not part of the study sample. All six participants reported having various functional limitations and going outdoors in the winter at least twice a week. Each participant first took part in an observation session, then an interview session. During the observation session, the participant took a walk (approximately 45 min long) on a familiar, self-chosen route, for example, from their home to the local senior center, together with an observer. During the walk, the participant was systematically observed and any critical incidents (such as slips, trips, or falls) occurring was recorded either through the observer’s annotations or by the participant’s own remarks. The participant was also encouraged to recall any incidents (such as a pedestrian facility obstructed by snow or ice) that occurred in the last three winters. Afterwards, the walk was further discussed with the participant during an interview consisting of the following themes:

- Outdoor locations that are challenging or problematic in the winter

- Specific incidents/problems at the identified locations and ideas on changes/improvements

- Strategies that they use to manage the winter, changes in outdoor travel habits over the years and reasons for such changes

The qualitative information was transcribed and analyzed with content analysis in order to find general patterns and to categorize identified problematic locations (pedestrian facilities), problems perceived at each locations, and winter coping strategies. It resulted in nine outdoor locations, six perceived problems, and eight winter coping strategies. After these items were discussed among the expert committee and the healthcare professionals, 23 items were worded into questions forming a pilot questionnaire. In order to strengthen the validity and reliability of the pilot questionnaire, it was tested on another three older people who were not part of the study sample. Potential misunderstandings were found for two questions which were reworded. The final core part of the questionnaire comprised 13 structured questions and three open-ended questions.

In this part of the questionnaire, participants rated their overall perception of the outdoor environment in the winter by answering the following question: “Do you have any problems getting around outdoors (walking, or using wheelchairs or scooters, etc.) in the winter?” with the response alternatives “yes” and “no”. In addition, the respondents were asked to state the problems perceived at nine specific outdoor locations. The nine outdoor locations were sidewalks, street crossings, curb ramps, outdoor stairs and ramps, building or transit entrances, bus stops, roads without sidewalks, and driveways. The response alternatives for each location were: “I do not use this location in the winter”, “I have never experienced any problems at this location during the winter”, “icy surface”, “snowy/slushy surface”, “snow bank”, “puddle”, “splashed by passing automobiles”, and “reduced visibility”. Respondents could choose more than one item for each location and fill in “Other” perceived problems not listed. Then the respondents were asked to indicate one location which caused the greatest concern in the winter. With respect to preferred coping strategies, the respondents were asked: “How do you manage the problems you have getting around outdoors in the winter?” The response alternatives were: “stay home”, “go out less”, “be more careful”, “avoid the area/location”, “use ice grip devices”, “get assistance from others”, and “rely more on automobiles instead of walking”; it was possible for the respondents to report use of more than one strategy or fill in “other” strategies not listed. The questionnaire ended with one open-ended question that asked the participant to provide comments and suggestions on how to improve accessibility during the winter.

Statistical Analysis

Due to use of ordinal data, skewed data distributions, and the small sample sizes, nonparametric tests were used in this study. Differences between the three age groups with regard to perceived functional limitation, frequency of outdoor excursion, whether having problems with getting around outdoors, and using of winter coping strategies were tested by the chi-square test. Differences in frequency of outdoor excursion, whether having problems with getting around outdoors, and using of winter coping strategies between respondents who reported at least one functional limitation and those who had no limitations were also assessed by means of the chi-square test. Differences between the three conditions were tested by means of the Wilcoxon matched pairs test with regard to frequency of outdoor excursion in the three age groups and in people with or without functional limitations. All analyses were accomplished using Statistica software (version 5.5; Statsoft; Tulsa, OK). P values below 0.05 were considered significant in all tests.

Results

General Information and Functional Limitations

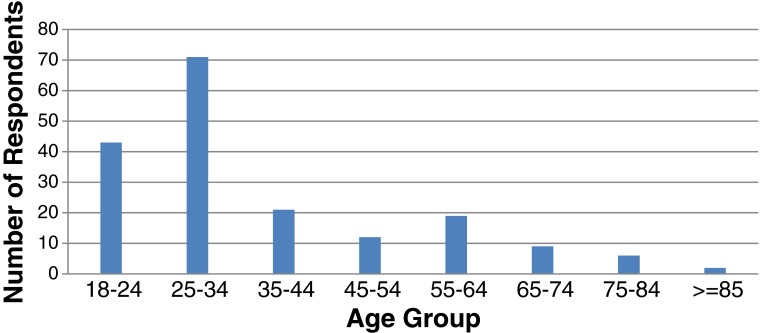

The characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. The young age group (18–34 years) included 114 participants, the middle aged group (35–59 years) had 42 participants and the older aged group (60–85 years) included 27 participants. The age distribution of the respondents is shown in Figure 1 and income distribution is shown in Figure 2. Of all the respondents, 47 % stated that they had at least one functional limitation (mobility, hearing or sight) that sometimes affected their ability to perform routine activities. The results showed that 77 % of the older participants had at least one functional limitation, compared to 57 % of the middle-aged and 39 % of the young participants (Table 1). Chi-square tests found significant differences between young and middle-aged groups (p = 0.04) and between young and older groups (p = 0.002), but there was no significant difference between middle-aged and older groups (p = 0.16). A significantly higher proportion of the female respondents (55 %) compared to male respondents (37 %) reported at least one functional limitation (chi-square test, p = 0.02). Among the 69 participants who further pointed out that their limitations affected their ability to perform routine activities, 43 (62 %) were most affected by mobility limitations (arm, leg, and/or back), 15 (22 %) were most affected by sight limitations and 3 (4 %) were affected by hearing limitations, and 8 (12 %) reported that other conditions (for example: height extremes or respiratory problems) affected their ability to perform routine activities the most. Despite the high proportion of respondents who reported at least one functional limitation, only 8 % (n = 13) of them indicated that they used assistive devices. Six respondents used canes, five used wheelchairs, one used a scooter, and one used a hearing aid.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents

| Characteristics | Young | Middle aged | Older | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 Years | 35–59 Years | 60–85 Years | |||

| N = 114 (%) | N = 42 (%) | N = 27 (%) | N = 183 (%) | ||

| % Female | 62 | 69 | 74 | 66 | |

| Functional limitations (FL) | Mobility | 27 | 50 | 59 | 36 |

| Hearing | 6 | 11 | 52 | 13 | |

| Sight | 11 | 16 | 43 | 16 | |

| At least one FL | 39 | 57 | 77 | 47 | |

| Use of assistive device | 2 | 17 | 19 | 8 | |

| Had problems getting around outdoors in the winter | 17 | 36 | 56 | 27 | |

Figure 1.

Age distribution of the respondents.

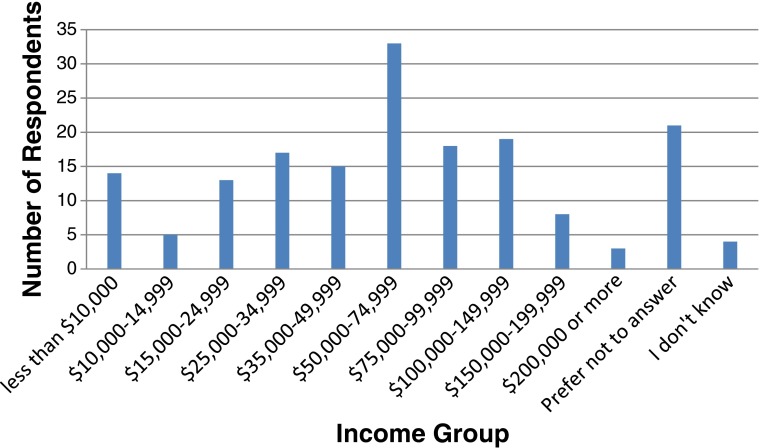

Figure 2.

Income distribution of the respondents.

In order to investigate to what extent the weather and surface conditions affected participants’ outdoor excursion frequency, participants were asked to recall the weekly frequency of outdoor excursions in a typical autumn week, and a winter week with or without snow/ice on the ground. As shown in Table 2, when the outdoor environment gradually deteriorated, people tended to go out less frequently regardless of their age. During a typical week in autumn (comfortable condition), 86 % of respondents went out at least once per day, this rate decreased to 82 % during a winter week when there was no snow and/or ice on the ground (less comfortable condition). However, the decrease was only significant in young respondents (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p = 0.001) but not in middle-aged and older respondents (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p = 0.08 and p = 0.46, respectively). During a winter week when there was snow and/or ice on the ground (difficult condition), only 66 % of respondents went out at least once per day, which was significantly lower than in an autumn week (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p < 0.0001) and in a winter week when there was no snow and/or ice on the ground (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p < 0.0001). The decreases of frequency of outdoor excursion when snow or ice was present were even more pronounced in the older adults, the rate dropped from 67 % in a winter week without snow/ice to 42 % in the snowy/icy condition (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p = 0.0003) compared to a drop from 85 to 71 % in the middle-aged adults (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p = 0.0007) and a drop from 84 to 70 % in the young adults (Wilcoxon matched pairs test, p < 0.0001). When snow or ice was present, the differences between young and older groups and between middle-aged and older groups were statistically significant (chi-square test, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Distribution and differences in frequency of outdoor excursion among three age groups (Y, young (18–34 years, n = 112); M, middle-aged (35–59 years, n = 41); O, older (60–85 years, n = 24))

| Frequency of outdoor excursions, n | Autumn | Winter without snow/ice | Winter with snow/icea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | M | O | Yb | M | O | Yb, c | Mb, c | Ob, c | |

| More than 1 time per day | 82 | 31 | 11 | 66 | 25 | 11 | 46 | 19 | 3 |

| 1 time per day | 20 | 4 | 5 | 28 | 10 | 5 | 32 | 10 | 7 |

| 3–6 times per week | 8 | 6 | 7 | 17 | 6 | 5 | 30 | 8 | 6 |

| 2 times per week | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 time per week | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rarely | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| At least once per day | 91 % | 85 % | 67 % | 84 % | 85 % | 67 % | 70 % | 71 % | 42 % |

| 86 % | 82 % | 66 % | |||||||

aSignificant difference between young and older groups and between middle-aged and older groups

bSignificant difference from the autumn condition in the same age group

cSignificant difference from the winter without snow/ice condition in the same age group

A significantly lower proportion of respondents who reported one or more functional limitation (82 %) went out at least once per day during a typical week in autumn, compared to 94 % of those who did not report any functional limitation (chi-square test, p = 0.01). During a winter week when there was no snow and/or ice on the ground, 78 % of respondents who reported one or more functional limitation went out at least once per day and this rate decreased significantly to 67 % during a winter week when there was snow and/or ice on the ground. For respondents who reported no functional limitations, 89 % of them went out at least once per day during a winter week when there was no snow and/or ice on the ground, and this rate dropped to 72 % when snow or ice was present. The difference in the frequency of outdoor excursions between these two groups was not significant during winter weeks with or without snow/ice on the ground (chi-square test, p = 0.07 and 0.48, respectively).

Experiences While Getting Around Outdoors in the Winter

All 183 respondents commented on whether they had problems moving around outdoors in the winter. Of all the respondents, 27 % stated that they had problems moving around outdoors in the winter. The results showed that 56 % of the older participants had problems, compared to 36 % of the middle aged and 17 % of the young participants (Table 1). Chi-square tests found significant differences between young and middle-aged groups (p = 0.01) and between young and older groups (p < 0.0001), but there was no significant difference between middle-aged and older groups (p = 0.10). Among the respondents who had functional limitations, a significantly higher proportion (32 %) indicated that they had problems moving around outdoors in the winter, compared to 18 % of those who did not report a functional limitation (chi-square test, p = 0.04).

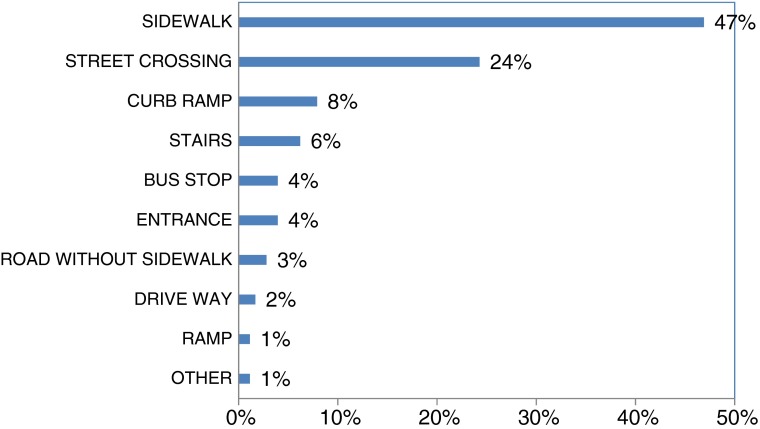

Figure 3 illustrates the outdoor locations that were of greatest concern to respondents across the three age groups. In total, 47 % of respondents chose the sidewalk as their greatest concern, while 24 % chose the street crossing and 8 % chose the curb ramp. Other locations mentioned by the respondents included stairs, bus stops, building or transit entrances, and driveways. There was no significant difference across the three age groups or between respondents with or without functional limitation.

Figure 3.

Outdoor location that concerned the respondents the most when they were taking outdoor excursions in the winter. Six respondents did not respond to this question, leaving us with reports from 177 persons.

Since the locations that concerned the respondents the most were sidewalks, street crossings, and curb ramps, the problems that were experienced by all respondents at these three locations were further analyzed. Of the 179 respondents who completed the question on sidewalks, four young participants and one older participant reported that they had never experienced any problems using sidewalks during the winter. Of the 182 respondents who completed the question on street crossings, one young participant and one older participant reported that they did not use street crossings in the winter and nine young participants, one middle aged and one older participant reported that they had never experienced any problems using street crossings during the winter. Of the 183 respondents who completed the question on curb ramps, five young participants and one middle-aged participant reported that they did not use curb ramps in the winter and eight young participants, one middle aged and two older participants reported that they had never experienced any problems using curb ramps during the winter. The results (Table 3) showed that the problems with sidewalks most frequently experienced by all respondents were icy surfaces (81 %), snow bank (70 %), and snowy/slushy surfaces (69 %). At street crossing, the problems most frequently experienced by all respondents were snowy/slushy surfaces (71 %), snow banks (68 %), and puddles (63 %). At curb ramps, the problems most frequently experienced by all respondents were snowy/slushy surfaces (65 %), puddles (64 %), and snow banks (58 %). Other problems cited by the respondents at these three locations included walking on metal manhole covers in the sidewalk, high snow banks obstructing pedestrians and drivers from seeing each other, and difficulties in distinguishing the curb ramp from the sidewalk. There was no significant difference across three age groups or between respondents with or without functional limitations.

Table 3.

Percentages of respondents experienced the various problems in the winter at three locations (side walk, street crossing, and curb ramp)

| Sidewalk | Crossing | Curb ramp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 179 (%) | n = 182 (%) | n = 183 (%) | |

| Did not use in the winter | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Had no problem during the winter | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| Icy surface | 81 | 59 | 55 |

| Snow bank | 70 | 68 | 58 |

| Snowy / slushy surface | 69 | 71 | 65 |

| Puddle | 60 | 63 | 64 |

| Splashed by passing automobiles | 15 | 54 | 46 |

| Reduced visibility | 15 | 16 | 7 |

| Other | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Winter Coping Strategies

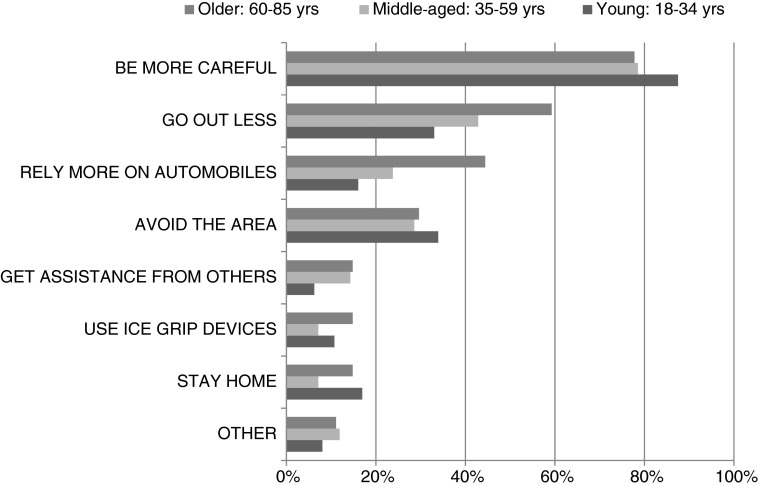

Chi-square tests showed that there were significant differences between young, middle-aged, and older respondents in relation to winter coping strategies. Of the older group, the strategies reported most often were “be more careful” (78 %), “go out less” (59 %), and “rely more on automobiles instead of walking” (44 %) as shown in Figure 4. Among young and middle-aged respondents, the strategies reported most often were “be more careful” (88 and79%, respectively), “go out less” (33 and 43 %, respectively), and “avoiding the area/location” (34 and 29 %, respectively). A significantly higher proportion of older respondents relied more on automobiles (44 %), compared to young respondents (16 %; chi-square test, p = 0.001). Besides the provided options, 17 respondents stated other strategies such as “use a gym for exercise rather than my usual outdoor walk” or “walk on the street instead of the sidewalk”. The difference between respondents with and without functional limitations in relation to winter coping strategies was not significant.

Figure 4.

Winter coping strategies reported in the survey by age group.

Eighty-three participants responded to the open-ended question with suggestions for solutions to outdoor accessibility in the winter. A range of general suggestions included: better snow and ice removal on sidewalks, engineer away the puddles at the bottom of curb ramps, use a slip-resistant surface on stairs, keep bus stops free of snow banks, and color the sidewalk so as to make “hidden” ice visible.

Discussion

This explorative study showed that cold temperature itself had little impact on the frequency of outdoor excursions in the middle-aged and older respondents. However, the presence of snow and/or ice on the ground noticeably kept people, especially older adults at home. The older pedestrians went out less when there was snow and ice on the ground, more older adults and people with functional limitations had problems moving around outdoors in the winter, and a significantly higher proportion of older respondents relied more on automobiles in the winter. The respondents generally were more concerned with icy surfaces at sidewalks, while at street crossings and curb ramps they were more concerned with snowy/slushy surfaces and puddles. Street crossings, sidewalks, curb ramps, and bus stops are key elements of a community infrastructure that support safety, security, mobility, activity, and engagement in public life. They play an important role in the development of livable communities by creating walkable neighborhoods and an accessible public realm. Considerable information has been available on accessible design of these pedestrian facilities since the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law in 1990,26–28 but there is no systematic research on how they can be designed to remain usable in all weather conditions. Our results suggest that snow and ice dramatically changes the accessibility of these pedestrian facilities. Future studies are needed to confirm our findings and more fully understand how weather impacts accessibility as well as how to improve winter accessibility.

We found that respondents went out less in the winter. These findings are consistent with results from other studies.29–32 Tucker and Gilliland32 noted that precipitation, cold weather, and wind were the deterring factors to physical activity in many parts of Canada and the northern USA. However, despite associations between leisure activity and seasonality, weather has generally not been found to be a barrier to physical activity when controlling for other potential confounders. King et al.33 found that weather was not reported to be a strong personal barrier to physical activity, and consequently was not independently associated with physical activity among a sample of US adult women (40 years of age or older). One possible explanation for the weak association between cold weather and outdoor activities among middle-aged and older adults might be that slippery surface conditions (covered by snow, slush, or ice) presented a bigger barrier than cold temperatures alone. Our study added to the results of the few existing studies on frequency of winter outdoor activities by providing more information about specific outdoor hazards. Icy sidewalk surfaces, and puddles and slush at curb ramps were the most frequently named barriers and concerned the pedestrians the most in the winter. Furthermore, the results showed that there were no significant differences between age groups and between people with or without functional limitations on overall perception of concerned location and the number of problems at each of the three locations (sidewalk, street crossing and curb ramp) in the winter. These findings suggest that winter weather and surface conditions greatly exacerbate the barriers in the pedestrian environment to the extent that even people without any functional limitations are sharing the same concerns as those who have functional limitations.

Streets, roads, and sidewalks are most often used by older adults for leisure time physical activity,34,35 but our results suggest that walking on sidewalks or roads in the winter may be dangerous because of icy surfaces, snow banks, and other hazards. As found in this study, icy surfaces were the number one concern on sidewalks, whereas puddles and slushy/snowy surfaces were the top concerns at curb ramps and street crossings (Table 3). Street crossings are important elements that connect sidewalks and streets. Curb ramps are essential components of the sidewalk network because they provide accessibility to wheelchairs, baby strollers, and other mobility aids at intersections and other areas where the sidewalk is elevated by a curb. The curb ramp was designed in Berkeley, California and is the current standard of accessibility. While the current design of curb ramp is successful in temperate climates such as California, it is especially ineffective in locations with cold winters because the curb ramp pools with rain, snow, and ice, often making it hazardous and inaccessible to nearly all users. The ADA has guidelines for maintaining the accessibility of sidewalks. All sidewalks and curb ramps must be clear of snow allowing at least the legal minimum width for travel. Our previous study audited the extent to which barriers resulting from winter precipitation form at curb cuts in downtown Toronto and found that 44 % of all the curb ramps had puddles covering more than one half the width of the pedestrian crossing.36 Ryser and Halseth suggested that care should be taken to modify curb details where snow and ice are prone to gather.15 Of 32 % of the respondents (n = 57) who chose the street crossing or curb ramps as their greatest concern, the majority of them (77 %) commented on how puddles of snow/ice/slush formed at the bottom of the curb ramps and made it very difficult to cross the street. One participant commented that “curb cuts are absolutely awful in the winter. There are usually huge snow banks to climb over and then no drainage of melting snow on the street side so that when you jump across, you usually land in an impossibly large puddle. This is all while paying attention to turning vehicles and trying to cross the street while the light is still green. Safety is a huge concern.” Another participant commented that “curb cuts are usually flooded with water/slush. I need to step over/around the puddles to make it onto the street.” It is the combination of the gutters along the sides of the road used to drain water to catch basins and the slope of the curb ramp that creates a reservoir effect collecting and trapping precipitation directly in the paths of pedestrians attempting to cross the road.

The current design of curb ramps causes many street crossings in the Toronto area to have poor accessibility throughout the winter months (Figure 5b and c). This is illustrated well in Figure 5c which shows an image taken after the sun melted all the snow at one intersection. The only place where pedestrians cannot access the crosswalk is at the curb ramp. After observing snow and ice removal at the intersection and interviewing the District Superintendent in charge of managing snow removal in the Toronto area, it was clear that improving winter pedestrian conditions is not simply a matter of sending more plows out on the roads. It was observed that under rainy and light snow conditions, the puddles at the bottom of curb ramps remained for long periods of time even when the sidewalks were free of snow and ice. Although there are different types of curb ramps and it is required that curb ramps be adequately drained,28 to our best knowledge, no alternative designs of curb ramp have been developed to successfully address the issue of the accumulation of water/snow/slush/ice at the bottom of the ramp. Given the extreme weather conditions associated with Canada’s winter climate, pedestrian safety concerns require civil engineers and urban planners not only to address the need for prompt and efficient snow and ice removal from sidewalks, but also to promote the need for alternative designs of street crossings and curb ramps that take into account winter conditions and to evaluate the effectiveness of such environmental improvements.

Figure 5.

Curb ramp conditions in summer (a) and winter (b) and (c), Toronto, Canada.

Compared to previous studies,37,38 the present study included a higher proportion of participants with functional limitations (47 %, Table 1). It was not our intention to determine the proportion of the general population who has specific opinions on mobility difficulties created by winter weather. Our goal was to identify the relative importance and frequency assigned to different issues by a population that includes a high proportion of people with mobility limitations.

Additional perceived problems revealed in the survey responses included “highways” (a nonpedestrian location) mentioned by one participant, as well as metal plates in the sidewalk, drivers not paying attention to pedestrians, indistinguishable curb ramps, and a lack of railings for outdoor stairs. Participants also elaborated on some of the winter coping strategies that were provided and two participants mentioned that they would use the road instead of the sidewalk. Additional perceived problems specific to each location should be added to the next round of questionnaires and it is recommended that such revisions to our questionnaire be included in future studies.

Study limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the design and the self-report of functional limitation. Another limitation of this study is that data about a respondent’s education level was not collected. People with lower incomes or lower education levels, are less likely to participate in surveys and those in the lowest educational category tend to be underrepresented.39 Therefore, other methods need to be developed in the future to increase the participation of underrepresented groups, such as focus group or observational methods. Additionally, our findings are limited by a low response rate and relatively small, predominantly female (66 %) and young (62 %) sample. We designed our study (hybrid sampling method and offering a lottery incentive) to maximize the yield of responses within a limited time frame. We also used statistical comparisons that account for the small sample size. However, future studies with larger samples of older adults who have mobility limitations are needed to confirm our current results and more fully understand how weather impacts accessibility. Another study limitation is that environmental exposure was considered only in terms of outdoor excursion frequency, use of the nine outdoor locations in the winter and any problems experienced at the locations, as real-time data on actual behavior and activities is not possible to gather by means of a survey questionnaire. Accordingly, future iterations of tools for assessing outdoor facilities could take advantage of technologies such as GPS devices to track location in space and time combined with local meteorological information to collect data regarding the complex interrelationship between environmental exposure, perception and activities as well as the impact of weather on mobility and accessibility.

Conclusions

The present study emphasized the need to plan for multiseason pedestrian environments. The data from the survey illustrated that the key elements that decreased winter accessibility were icy surfaces on the sidewalk and slush/puddles at street crossings and curb ramps. The results of this study shed some light on the effect of winter weather and surface conditions on the perception of winter accessibility, showing that cold temperatures alone had little impact on the frequency of outdoor excursions among middle-aged and older adults while the presence of snow and/or ice on the ground noticeably kept people, especially older adults, at home. On the other hand, winter weather and surface conditions greatly exacerbate the barriers in the pedestrian environment to the extent that people without any functional limitations are sharing the same concerns as those who have functional limitations. Given the extreme weather conditions associated with Canada’s winter climate, pedestrian safety concerns require civil engineers and urban planners not only to address the need for prompt and efficient snow and ice removal from sidewalks, but also to promote the need for alternative designs of street crossing and curb ramp that take into account winter conditions and evaluate the effectiveness of such environmental improvements. It should be acknowledged that only a limited number of comparable studies on winter accessibility have been reported to date. Thus, while our results must be regarded as preliminary, they also indicate that our questionnaire has the potential, to be further developed into an outdoor assessment tool, for revealing and prioritizing the needs of users.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) through the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Universal Design and the Built Environment (grant #H133E050004-08A), a partnership with the Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access (IDEA). We also acknowledge the support of Toronto Rehabilitation Institute who receives funding under the Provincial Rehabilitation Research Program from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario. Equipment and space have been funded, in part, with grants from the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the Province of Ontario. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of these organizations. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Leslie Beard, Michael D. Grimble, and Dylan Reid for their invaluable assistance during data collection.

References

- 1.Wennberg H, Stahl A, Hyden C. Older pedestrians’ perceptions of the outdoor environment in a year-round perspective. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6(4):277–90. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0123-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muraleetharan T, Meguro K, Adachi T, Hagiwara T, Kagaya S. Influence of winter road conditions and signal delay on pedestrian route choice in Japan’s snowiest metropolis. Transp Res Rec. 2005;1939:145–53. doi: 10.3141/1939-17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li W, Keegan THM, Sternfeld B, Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Kelsey JL. Outdoor falls among middle-aged and older adults: a neglected public health problem. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1192–200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg WP, Alessio HM, Mills EM, Tong C. Circumstances and consequences of falls in independent community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing. 1997;26(4):261–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talbot LA, Musiol RJ, Witham EK, Metter EJ. Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC Publ Health. 2005;5:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humpel N, Marshall AL, Leslie E, Bauman A, Owen N. Changes in neighborhood walking are related to changes in perceptions of environmental attributes. AnnBehav Med. 2004;27(1):60–7. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmon J, Crawford D, Owen N, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a population-based study of barriers, enjoyment, and preference. Heal Psychol. 2003;22(2):178–88. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dasgupta K, Joseph L, Pilote L, Strachan I, Sigal RJ, Chan C. Daily steps are low year-round and dip lower in fall/winter: findings from a longitudinal diabetes cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2010;66(5):474–6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klenk J, Büchele G, Rapp K, Franke S, Peter R. Walking on sunshine: effect of weather conditions on physical activity in older people. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;66(5):474–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.128090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCormack GR, Friedenreich C, Shiell A, Giles-Corti B, Doyle-Baker PK. Sex- and age-specific seasonal variations in physical activity among adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(11):1010–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.092841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CB, Ryan DAJ, Tudor-Locke C. Relationship between objective measures of physical activity and weather: a longitudinal study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Togo F, Watanabe E, Park H, Shephard RJ, Aoyagi Y. Meteorology and the physical activity of the elderly: The Nakanojo Study. Int J Biometeorol. 2005;50(2):83–9. doi: 10.1007/s00484-005-0277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dewar RE. Pedestrians and bicyclists. In: Dewar RE, Olson PL, editors. Human factors in traffic safety. Tucson: Lawyers & Judges; 2002. pp. 557–612. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nabors D, Gibbs M, Sandt L, Rocchi S, Wilson E, Lipinski M. Pedestrian road safety audit guidelines and prompt lists. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryser L, Halseth G. Institutional barriers to incorporating climate responsive design in commercial redevelopment. Environ Plan B: Plan Des. 2008;35(1):34–55. doi: 10.1068/b32066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwarsson S, Stahl A. Accessibility, usability and universal design—positioning and definition of concepts describing person–environment relationships. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(2):57–66. doi: 10.1080/dre.25.2.57.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity. A review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(3):188–99. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moudon AV, Lee C. Walking and bicycling: an evaluation of environmental audit instruments. Am J Heal Promot. 2003;18(1):21–37. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugiyama T, Thompson CW. Outdoor environments, activity and the well-being of older people: conceptualising environmental support. Environ Plan A. 2007;39(8):1943–60. doi: 10.1068/a38226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinhardt JD, Miller J, Stucki G, Sykes C, Gray DB. Measuring impact of environmental factors on human functioning and disability: a review of various scientific approaches. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(23–24):2151–65. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.573053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander M, Matthews D. Pediatric Rehabilitation: P & P, 4th Edition: Principles & Practices: Fourth Edition. Demos Medical; 2009.

- 22.Boschen KA, Tonack M, Gargaro J. The impact of being a support provider to a person living in the community with a spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2005;50(4):397–407. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.50.4.397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boucher N, Dumas FB, Maltais D, Richards CL. The influence of selected personal and environmental factors on leisure activities in adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(16):1328–38. doi: 10.3109/09638280903514713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinfeld E. Access to the built environment: a review of literature. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danford GS, Grimble MD, Maisel J, editors. Benchmarking the Effectiveness of Universal Design. Annual Research Conference of the Architectural Research Centers Consortium : leadership in architectural research, between academica and the profession 2009; San Antonio, TX.

- 26.Axelson PW, Chesney DA, Galvan DV, Kirschbaum JB, Longmuir PE, Lyons C, et al. Designing sidewalks and trails for access, part I of II: review of existing guidelines and practices: US Dept. of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration; 1999.

- 27.Dawson D. Designing accessible facilities in the public right-of-way. ITE J (Inst Transp Eng) 2004;74(9):46–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirschbaum JB, Administration FH, States U. Designing sidewalks and trails for access part II of II: best practices design guide: US Dept. of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration; 2001.

- 29.Suminski RR, Petosa RL, Stevens E. A method for observing physical activity on residential sidewalks and streets. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):434–43. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews CE, Freedson PS, Hebert JR, Stanek Iii EJ, Merriam PA, Rosal MC, et al. Seasonal variation in household, occupational, and leisure time physical activity: longitudinal analyses from the seasonal variation of blood cholesterol study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(2):172–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pivarnik JM, Reeves MJ, Rafferty AP. Seasonal variation in adult leisure-time physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(6):1004–8. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000069747.55950.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tucker P, Gilliland J. The effect of season and weather on physical activity: a systematic review. Public Health. 2007;121(12):909–22. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King AC, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler AA, Sallis JF, Brownson RC. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial—ethnic groups of U.S. middle-aged and older-aged women. Heal Psychol. 2000;19(4):354–64. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Bacak SJ, Housemann RA. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(9):1529–36. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084622.39122.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huston SL, Evenson KR, Bors P, Gizlice Z. Neighborhood environment, access to places for activity, and leisure-time physical activity in a diverse North Carolina population. Am J Heal Promot. 2003;18(1):58–69. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu J, Li Y, Fernie G, Saundercook B. How current pedestrian crossings fail in winter weather and the need for experimental intersections to design for safety. 8th Annual International Conference on Walking and Liveable Communities; New York City, 2009.

- 37.Altman B, Bernstein A. Disability and health in the United States, 2001–2005. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Participation and Activity Limitation Survey 2006: analytical report. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berra S, Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Tebé C, Bisegger C, Duer W, et al. Methods and representativeness of a European survey in children and adolescents: the KIDSCREEN study. BMC Public Health. 2007. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]