Abstract

Temperament, effortful control, and problem behaviors at 4.5 years were assessed in 72 children classified as exuberant, inhibited, and low-reactive as 2-year-olds. Exuberant toddlers were more positive, socially responsive to novel persons, less shy, and rated as having more problem behaviors including externalizing and internalizing behaviors, than other children as preschoolers. Two forms of effortful control, the ability to delay a response and the ability to produce a subdominant response, were associated with fewer externalizing behaviors, while expressing more negative affect (relative to positive/neutral affect) when disappointed was related to more internalizing behaviors. Interaction effects implicated high levels of unregulated emotion during disappointment as a risk factor for problem behaviors in exuberant children.

Keywords: temperament, externalizing, internalizing, exuberant, inhibited, toddlers

One of the primary aims of developmental research is to identify pathways from early behavior to later childhood competence, or alternatively, to behavioral dysfunction. One construct that has received considerable research attention for its theoretical and empirical links to these outcomes is temperament. In the present study we examined developmental outcomes, specifically externalizing and internalizing behavior, of children varying on the temperament dimensions of approach and inhibition. This research is based on the theoretical model which proposes that temperament may have a critical role in the development of psychopathological conditions (Frick & Morris, 2004; Rothbart, Posner, & Hershey, 1995). Likewise, our study is informed by the developmental psychopathology framework (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1998) which emphasizes the application of normative development to understanding atypical populations and the study of individual developmental pathways as essential to identifying those most likely to develop maladaptive behaviors.

Several pathways by which temperament may be related to high-risk conditions or psychopathology have been proposed (Rothbart et al., 1995). Psychopathology, for example, may directly map onto a temperamental extreme, as when an infant who has difficulty attending for long periods develops attention deficit disorder. Temperament may also contribute to psychopathology by providing a context that interacts with other factors to increase the probability of a disorder. A tendency to be easily frustrated, for example, may create difficulties interacting with peers, which in turn may lead to heightened aggression. On the positive side, temperament may also act as a buffer to conditions that put a child at risk, as in the example of a child living in poverty who is predisposed toward positive affect.

Two interconnected temperament dimensions often linked to risk for psychopathology are approach and inhibition (Nigg, 2000; Rothbart et al., 1995). Historically, this concept has been considered a unitary dimension reflecting a predisposition to approach or withdraw from novel or unfamiliar events, which was central to theories in comparative and personality psychology (Cloninger, 1987; Gray, 1982; Schnierla, 1959). More recently, it has been applied to the study of infant and child temperament (Asendorpf, 1990; Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001; Kagan & Snidman, 1991; Thomas & Chess, 1977), and behavioral distinctions have been drawn between indices of approach and inhibition (Fox et al., 2001; Putnam & Stifter, 2005). In a series of longitudinal studies, Kagan and colleagues (Garcia-Coll, Kagan, & Reznick, 1984; Kagan, 1994; Kagan & Snidman, 1991) have investigated a cluster of behaviors and biological concomitants labeled “behavioral inhibition.” Using an extreme group approach, these studies have demonstrated that the predisposition to be fearful and avoid new and unfamiliar events is relatively stable, associated with several physiological measures reflecting sympathetic activation, and predictive of social withdrawal (Biederman et al., 2001; Kagan, 1994; Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987; Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002). On the flip side, behaviorally uninhibited children, those who readily approach novel persons and objects, have been shown to exhibit the opposite profile. Although some stability has been identified in behavioral inhibition, particularly among children at the extreme end of the continuum, discontinuity has also been found particularly when moderating factors are considered. Parenting, child care, and IQ, for example, have been shown to influence change in inhibition (Asendorpf, 1994; Fox et al., 2001; Park, Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1997). Interestingly, while the majority of inhibited children became less fearful over time, the behavioral style, uninhibited or “exuberant,” has shown considerable stability (Fox et al., 2001; Pfeifer, Goldsmith, Davidson, & Rickman, 2002).

The link between approach/inhibition tendencies and risk for psychopathology has been investigated extensively in older children and adults. Much of this work is based on the neurological models of Gray (1982) who proposed a Behavioral Approach System (BAS) and Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS). The BAS is presumed to motivate behavior toward positive incentives whereas the BIS leads to avoidance of stimuli signaling punishment. Research has linked dominance of BAS over BIS functioning to externalizing problems, with BIS dominance implicated in internalizing difficulties. For instance, both the desire to engage in novel and intense activities (approach motivation), and the willingness to take risks for the sake of such experiences (a lack of inhibition), has been related to manic, bipolar, and antisocial personality disorders in adults (Zuckerman, 1994), and to elevated rates of conduct disorder, high levels of self-reported negative behaviors, and low rates of internalizing problems in children (Colder & O’Connor, 2004; Frick & Morris, 2004; Kafry, 1982). BIS dominance, on the other hand, is proposed to increase vulnerability to anxiety disorders (Gray, 1982). Empirical support for this relation can be found in studies with adults (Newman, Wallace, Schmitt, & Arnett, 1997) and children (Caspi, Henry, McGee, Moffit, & Silva, 1995). Observed fearfulness/fearlessness in young children has been related to later internalizing and externalizing behavior (Hirshfeld et al., 1992; Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 2000; Putnam & Stifter, 2002; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1996). A follow-up study of one of Kagan’s cohorts found children with stable behavioral inhibition to have significantly higher rates of anxiety disorders than children who were either uninhibited or had changed in behavioral inhibition across early childhood (Hirshfeld et al., 1992). And, although it might be expected that uninhibited toddlers would be at risk for externalizing behavior, only a few studies have examined and confirmed this relationship (Putnam & Stifter, 2005; Rubin, Coplan, Fox, & Calkins, 1995; Schwartz et al., 1996).

Not all children classified as exuberant or behaviorally inhibited are at risk for behavior problems. Indeed, the relationship between behavioral inhibition and internalizing is modest with several studies failing to find this link (Schwartz et al., 1996). Many developmental tasks are accomplished between the ages at which temperamental profiles of exuberance and behavioral inhibition are identified and problem behavior develops. Thus, whereas a particular style of temperament may put a child at risk for developing a set of problem behaviors, the emergence of new skills may decrease this likelihood. Following Rothbart (Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981), we conceive of temperament as having reactive and self-regulatory components. While variations in emotional reactivity are identifiable in early infancy, self-regulatory skills are proposed to come online in later infancy and function to modulate reactivity. Effortful control, a type of self-regulation, is a term used by Rothbart to describe individual differences in the ability to voluntarily inhibit a prepotent behavioral or emotional response and/or to generate a sub-dominant response. These skills emerge by 12 months and become more organized during the preschool years (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001; Kopp, 1982). Effortful control, therefore, may moderate approach or inhibition to affect later social competence/problem behavior. Indeed, several studies have shown effortful control to be directly and indirectly linked to behavioral adjustment in preschoolers (Murray & Kochanska, 2002), elementary school aged children (Eisenberg et al., 1996; Murray & Kochanska, 2002) and adolescents (Rothbart, Ellis, & Posner, 2004) In the present study we hypothesized that higher levels of effortful control would lessen the risk of problem behavior associated with approach and/or inhibition. To address this hypothesis we examined three functions of effortful control, (1) to suppress/delay a dominant response; (2) to suppress a dominant response for the purposes of producing a subdominant response; and (3) to regulate emotion.

Effortful control processes are primarily cognitive and proposed to be related to the development of the frontal lobe. In this way, effortful control is similar to executive function, a rubric for goal-directed problem solving that involves inhibitory control, attentional flexibility, planning, and working memory. Consistent with effortful control, the greatest growth in executive function (EF) occurs between 2 and 5 years of age (Zelazo, Carter, Reznick, & Frye, 1997). Executive function has been related to mental health outcomes, with executive function deficits identified in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Pennington, Groisser, & Welsh, 1993) and in conduct disordered adolescents, (Giancola, 1995; Moffit, 1993). Deficiencies in executive control are proposed to decrease the ability to generate alternative responses (e.g., non-aggressive, prosocial) to emotion-eliciting situations (Giancola, 1995). Related to the present study, EF, specifically inhibitory control and planning, was found to moderate the behavioral outcomes of “hard to manage” preschoolers (Hughes, White, Sharpen, & Dunn, 2000) such that those with lower EF were observed to be more antisocial than their peers with higher EF scores.

The distinction between the ability to suppress/delay a response and the ability to suppress a dominant response in favor of a subdominant response found in the definition of effortful control is similar to distinctions made in the executive function field. Carlson and Moses (2001) proposed these distinctions within inhibitory control, a component of executive function. They found that inhibitory control could be further discriminated into processes that delay a prepotent response and those that activate a conflicting novel response by suppressing a prepotent response. Underlying the difference between these processes, suggest Carlson and Moses, is the need for working memory in the conflict task. Zelazo and colleagues (Hongwanishkul, Happaney, Lee, & Zelazo, 2005; Zelazo & Muller, 2002) similarly distinguish these two processes but along affective lines. “Hot” EF is elicited by problems that require regulation of emotion, particularly if it involves reward, such as delaying gratification. “Cool” EF is more likely to be elicited by abstract, decontextualized problems such as the Stroop task. Importantly, these distinctions have been validated through differential prediction to theory of mind (Carlson & Moses, 2001; Jahromi & Stifter, in press) and general intelligence (Hongwanishkul et al., 2005). Due to the theoretical and empirical distinctiveness of these processes we considered how the ability to suppress/delay a response and the ability to produce a subdominant response each interacted with temperament style to predict problem behavior. Following Carlson and Moses we respectively labeled these processes “delay EF” and “conflict EF.”

Effortful control processes can also be recruited for the purposes of regulating emotions. Emotion self-regulation, emerges in infancy and has demonstrated significant development across early childhood (Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995; Stifter, 2002), moving from an external process dependent primarily upon caregiver intervention to a more self-reliant internal process. Indeed, by the preschool years it is difficult to assess whether a child is regulating their emotions or not reacting at all to an emotion-eliciting stimulus (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004; Thompson, 1994). Because emotion self-regulation functions to either attenuate or enhance emotional reactions, emotion regulation strategies that are effectively and consistently applied may change the behavioral appearance of a child. For example, a child who exhibited a low threshold for frustration in infancy may be at low risk for angry outbursts as a preschooler once he or she has developed emotion regulation skills. Alternatively, the inability to regulate frustration may increase risk of problem behavior. This hypothesis has been supported by research with toddlers (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000), preschool children (Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002), and school aged children (Eisenberg et al., 1996; Eisenberg et al., 2000).

The present study is a longitudinal examination of a sample of 2 year olds for which motoric approach/inhibition and positive and negative affect were coded from a series of tasks designed to elicit approach/inhibition (Putnam & Stifter, 2005). Taking a person-oriented approach we were able to identify children who failed to approach due to high inhibition from those who chose not to approach because of a deficit in approach activation. Cluster analysis identified three temperament groups; exuberant (high approach/positive affect), inhibited (low approach/negative affect) and low reactive (moderate approach/low positive and negative affect). In addition, we found a concurrent relationship between temperament and parent ratings of problem behavior. Exuberant toddlers were rated highest on the externalizing scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987) whereas inhibited toddlers were rated highest on the internalizing scale. Although these data suggest a link to developmental problems, problem behavior ratings at 2 years of age may reflect temperament (Lengua, West, & Sandler, 1998; Sanson, Prior, & Kyrios, 1990) and/or developmentally appropriate behaviors (Campbell, 1995). Thus, to verify whether approach and inhibition are risk factors for later problem behavior, we examined the longitudinal outcomes of these toddlers when they were 4.5 years of age.

It is important to note how the present study on inhibited and exuberant temperament differs from studies by Kagan (Kagan, 1994) and Fox (Fox et al., 2001) who have also studied these temperament types. Kagan’s inhibited and uninhibited groups were composed of toddlers who exhibited extremes (high and low) in negative reactions to unfamiliar persons and situations. He further demonstrated that these two groups could be predicted from earlier (4 month) reactivity to stimulation (Kagan, Snidman, & Arcus, 1998). In examining early precursors of inhibited and uninhibited temperament Fox showed that 4 month old infants who responded to novel events with positive affect, not lack of negative affect, went on to be uninhibited toddlers. Interestingly, although Fox and colleagues labeled these children “exuberant,” they did not use positive affect when measuring inhibition at later ages. In the present study toddlers were drawn from a community sample and categorized based on their negative and positive reactions to a “risk room” as well as their approach/inhibition behavior.

The first goal of the present study was to examine the stability and instability of approach and inhibition. We expected some stability in both dimensions as Kagan (1994) and others (Fox et al., 2001; Pfeifer et al., 2002) have shown inhibited and uninhibited behaviors to maintain their behavioral style across childhood. However, because these studies examined extreme groups we might expect less stability in the present sample, particularly from inhibited children who demonstrated significant change despite their original classification as extremely inhibited.

Our second goal was to examine longitudinal relations between approach/inhibition and problem behavior. Both direct and indirect relations were hypothesized. In our previous study, exuberant children exhibited more positive affect, particularly when engaged in new and exciting situations. But high approach children are also more likely to become frustrated (Rothbart, Evans, & Ahadi, 2000). High levels of “unrequited” approach (i.e., high frustration) may lead children to develop problem behaviors, particularly those of the externalizing type. Similarly, inhibited children who are highly fearful in novel and uncertain situations may develop anxieties that are maladaptive as they become more exposed to larger social groups. Given the emergence and consolidation of effortful control between the toddler and preschool years (Kopp, 1982), it was hypothesized that these skills would moderate the direct relation between temperament and problem behavior. In particular, the ability to apply effortful control in emotionally charged situations may assist the exuberant child in maintaining a positive orientation while managing a propensity to become angry. Such emotion self-regulation would buffer the likelihood that these children would develop externalizing problem behaviors. Although inhibited children have been found to possess higher levels of effortful control, variations in this skill may moderate the relation between inhibition and internalizing behaviors by overriding reactive attentional biases to threatening stimuli (Lonigan, Vasey, Phillips, & Hazen, 2004). Finally, because low-reactive children appear to be low on approach and inhibition processes, self-regulation may be less critical for successful adaptation among these children.

To examine the stability of approach/inhibition and its prediction to later behavior problems, we followed toddlers who were classified as exuberant, inhibited, and low reactive at 2 years of age. At 4.5 years of age, three forms of effortful control were measured: (1) the ability to suppress/delay a response for reward; (2) the ability to produce a novel response while suppressing a dominant response; and (3) the ability to regulate emotion when disappointed. Lastly, temperament across the 4.5 year lab tasks was assessed by observers and problem behavior checklists were completed by both parents.

Method

Participants

150 (78 females) infants were initially enrolled in a longitudinal study to examine the development of emotion regulation across the first two years of life. At two years of age, toddlers and their parents returned to the laboratory for two visits and 126 (63 females) participants were available for testing. For the preschool follow-up study, all families of the 126 toddlers were contacted and of these 72 (34 females) agreed to participate (27 had relocated and 27 declined to participate).1

Participants were drawn from predominantly white, educated, middle class families. Of the original sample, 5 infants were African American, 2 African, 3 Asian, and 1 Native American. All children at the 4.5-year follow-up were white (34 females). Maternal and paternal age at the time of recruitment into the study averaged 29.7 years (range 16 to 43) and 31.8 years (range 19 to 46), respectively. Education level for mothers averaged 15.6 years (range 10–26 years) and for fathers averaged 16.3 years (range 10 to 28 years). The majority of families reported their income to be between $50,000 and $75,000.

When children who returned for the 4.5-year follow-up were compared on the 2-year data used in the present study (see below) to those who were unable or chose not to participate, no significant differences were found, suggesting that attrition was random.

Procedures

2-Year Protocol

A series of tasks were used to elicit approach/inhibition in toddlers over two visits scheduled one month apart. In brief, toddlers were 1) introduced to a strange laboratory room; 2) approached by an unfamiliar female; 3) asked to look into a black box; 4) left with a “boring” toy to play with; 5) asked to jump off a series of stairs; 6) invited to play “ring around the rosie” with the stranger and parent; 7) given a choice between a high intensity and low intensity toys; 8) shown a champagne popper; 9) exposed to a vacuum cleaner. In addition, electrodes were placed on the child’s chest for the purposes of heart rate recording during one of the visits. Details of each of these tasks can be found in Putnam and Stifter (2005).

4.5-Year Protocol

Children returned to the laboratory for two visits at 4.5 years of age, once with their mothers and a second time with their fathers. The order of the first visit was 1) matching task; 2) ranking of toys for the disappointment task; 3) video vignettes; 4) emotion interview; 5) cognitive assessment; 6) disappointment; 7) structured play; 8) free play/clean up; 9) frustration task. During the second visit the following sequence of tasks was administered: 1) interview; 2) three pegs; 3) Day/Night Stroop; 4) delay of gratification; 5) walk-a-line; 6) structured play; 7) continuous performance task; 8) tapping task; 9) dinky toys; 10) free play/clean up; and 11) frustration task. Only the delay of gratification, dinky toys, three pegs, day/night, tapping, and the disappointment paradigm were used in the present study and are detailed below. All procedures were administered at a child-sized table and videotaped for off-line coding. The parent was in the room during the majority of all tasks unless otherwise noted. Although these tasks do not directly map onto Carlson and Moses’s (2001) distinction of delay and conflict tasks, we labeled two tasks that involved delay (delay of gratification, dinky toys) as Delay EF and the traditional EF tasks (three pegs, day/night, tapping) as Conflict EF. Furthermore, a factor analysis of the data resulting from these tasks suggested maintaining this distinction.2 While we recognize that regulation to the disappointment task likely requires executive control we elected to treat this emotional challenge separately as a moderator of temperament and labeled it emotion self-regulation.

Delay EF

Two tasks were used as measures of delay EF – delay of gratification and “dinky toys.” The delay of gratification task was taken from Mischel’s classic design (Mischel & Ebbesen, 1970). In the present study children were given a choice between two chocolate candies or goldfish crackers if they wait or one candy/cracker if they are not able to wait a set amount of time. Prior to the start of the procedure mothers were asked about their child’s preference for chocolate candy or goldfish crackers. Children were then told the rules and given a bell to ring if they could not wait. They were left alone in the room for a maximum of 15 minutes. If the child rang the bell before that time, the experimenter would return and the child would receive one candy/cracker. If they did not ring the bell, the experimenter returned after 15 minutes and the child was given the two candies/crackers.

In the dinky toys task (adapted from Goldsmith & Reilly, 1992) a clear, lidded container of small toys was presented to the child. The child was told that he/she could have one of the toys but should look carefully because once a toy was chosen he/she could not return the toy for another. The lid was removed and the child was allowed to look and choose but if he/she touched a toy, that toy was considered to be their choice.

Conflict EF

Three tasks designed to assess the child’s ability to inhibit a pre-potent response and produce a novel response were administered. The Three Pegs task required the child to tap colored pegs according to the experimenter’s instructions(Balamore & Wozniak, 1984). A wooden board with three differently-colored pegs, ordered red-yellow-green, was presented by the experimenter. A pretest insuring that the child understood the colors was conducted followed by a verbal instruction to the child to tap the pegs in the order – red, green, yellow. If the child tapped correctly a second trial was conducted. If the child tapped incorrectly then the experimenter demonstrated the task and asked the child to tap the pegs. If the child was correct a second trial was conducted. If incorrect, the child received a third demonstration.

The Day/Night task is a Stroop-like task (Gerstadt, Hong, & Diamond, 1994) that uses a set of cards containing black cards with a picture of a moon and white cards with a picture of a sun. When children saw the black card they were instructed to say “day” and when they saw the white card they were instructed to say “night.” After practice trials to test their understanding of the task were administered, 16 cards in a fixed random order were presented to the children and their responses recorded.

The Tapping task (Diamond & Taylor, 1996) required the child to learn and apply two rules. When the experimenter tapped the table with a stick once the child was to tap the table twice, and when the experimenter tapped the table twice the child was to tap the table once. If practice trials were passed (child performed both rules without a prompt) then the test trials were begun. If the child was incorrect the rules were re-demonstrated and then the test trials were administered. The 16 test trials were administered in a fixed random order.

Emotion self-regulation

To assess the child’s ability to regulate his/her emotional expression, the disappointment task was administered. Following Cole’s (Cole, 1986) procedure, the child was shown a tray of 5 toys and asked to first choose the one he/she liked best. The most-liked toy was put aside and then the child was asked which toy he/she liked the least. This procedure continued until all the toys were ranked. The child then participated in a number of tasks, the last of which was a receptive language test, after which the child was thanked and told he/she would receive a prize. The experimenter left the room with the parent and returned with a wrapped prize, which consisted of the toy that the child had ranked as the least favorite.

The experimenter handed the child the wrapped prize and sat across from the child while the child unwrapped the gift (experimenter-present condition). The experimenter remained in the room for 30 seconds attending to paperwork and did not engage the child during this time. After 30 seconds the experimenter left the room for 60 seconds (experimenter-absent condition). A second experimenter returned to the room to interview the child about the gift (how he/she felt about the prize, did he/she know that she gave them the wrong gift). The child was then given an opportunity to exchange the gift for any other gift on the tray.

Measures

2-Year Measures

Approach/Inhibition

Several behaviors that reflected approach and/or inhibition were coded from the videotapes of the two 2 year lab visits using coding systems created for the present study or adapted from previous studies (Fox et al., 2001; Kagan, Reznick, Snidman, & Garcia-Coll, 1984; Park et al., 1997). Proximity to parent was coded on a continuous basis using a scale ranging from 1 (clinging) to 5 (two or more steps away from parent). Reliabilities on 13% of the sample averaged .78 (Cohen’s kappa). The number of spontaneous nondistressed vocalizations was coded during all situations with the stranger (reliability on 14% of the data with 83% agreement). Activity level was coded during lab entry, boring toy and play with assistant tasks by applying a scale ranging from 0 (completely still) to 4 (running or vigorous movement) every 5 seconds (reliability on 14% with an average kappa of .80).

Several episode-specific ratings were made: 1) willingness to allow electrode placement (5-point scale from strongly avoids to no avoidance); 2) willingness to play ring-around-the-rosie game (5-point scale from actively refuses to immediately and enthusiastically joins in); 3) degree of exploration of the black box (6 point scale ranging from no approach to entire head inside box); 4) willingness to jump from steps (7 point scale ranging from no approach to jumps off prior to prompts); 5) off task behavior during the boring toy (coded every 5 seconds with a 3-point scale ranging from no off-task behavior to active engagement in off-task behavior). Finally, latencies to choose a low or high intensity toy were scored. If the child did not choose a toy, they were assigned a latency score of 20. Reliability was performed on 14% of the sample for the above ratings and Cohen’s kappas ranged from .80 to .85. Latency scores were reliable with 93% agreement.

Positive/Negative Affect

For all procedures, positive affect and negative affect were rated, based on facial and vocal expressions, from the videotapes using a global scale ranging from 0 (no affect) to 5 (continuous, high intensity affect). Reliability was calculated on 11% of the visits with kappas at .71 for positive affect and .73 for negative affect.

Group Formation

All measures from the 24/25-month visit were subjected to a Confirmatory Factor Analysis that supported a three factor model (details of this analysis are described in Putnam & Stifter, 2005) consisting of positive affect, negative affect, and approach/inhibition. A cluster analysis was then performed to create groups based on these three factors. Three groups were formed – 1) a group that was high in negativity and low in approach (inhibited), 2) a group that was high in positive affect and approach (exuberant), and 3) a group that was low on both emotion variables but moderate on approach/inhibition (low reactive). Gender was equally distributed across groups.

4.5-Year Measures

Delay EF

Latency to delay of gratification (ring bell or eat candy/cracker) and latency to choose a dinky toy were coded from the videotapes and calculated using a computer program. Children who waited the entire 15 minutes of the delay of gratification task were given a latency score of 900 seconds. A variable representing Delay EF was created by averaging the z-scores of the two latency variables. See Table 1 for the raw means and standard deviations for these data. There were no differences between temperament groups on the individual delay tasks or the composite.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for the study variables

| Total1 | Exuberant2 | Inhibited3 | Low Reactive4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Delay of gratification | 666.3 (348.7)5 | 640.0 (363.0) | 774.3 (319.6) | 635.6 (346.1) |

| Dinky toys | 27.1 (43.1)5 | 25.8 (38.7) | 38.3 (65.3) | 21.2 (28.3) |

| Three pegs | 2.04 (1.2) | 1.94 (1.2)a | 2.14 (1.0)a | 2.14 (1.3)a |

| Day/Night | 68.9 (24.5)6 | 60.8 (24.2)a | 74.7 (24.3)a | 65.3 (23.9)a |

| Tapping | 74.0 (30.0)6 | 81.2 (24.1)a | 55.6 (34.8)b | 76.4 (29.9)a |

| Emotion Regulation during Disappointment | .39 (.26)7 | .26 | .39 (.26) | .26 |

| Observed Activity | 5.2 (1.5)8 | 5.3 (1.3)a | 5.4 (1.7)a | 4.9 (1.6)a |

| Observed Response to Novel Persons | 3.2 (.76)9 | 3.5 (.60)a | 3.0 (.82)b | 3.0 (.85)b |

| Observed Positive Affect | 5.6 (1.3)8 | 6.0 (.87)a | 4.9 (1.5)b | 5.4 (1.3)b |

| Observed Shyness | 2.6 (1.4)8 | 2.1 (.89)a | 3.1 (1.4)b | 3.1 (1.7)b |

| Observed Task Persistence | 5.6 (1.7)8 | 6.0 (1.8)a | 4.7 (1.5)b | 5.6 (1.5)ab |

| CBCL Externalizing | 10.5 (7.8) | 13.3 (7.8)a | 7.2 (4.8)b | 9.1 (8.5)b |

| CBCL Internalizing | 4.5 (4.0) | 5.6 (4.6)a | 3.9 (3.6)b | 3.1 (3.0)ab |

| Total Behavior Problems | 25.4 (16.4) | 30.7 (17.0)a | 20.7 (10.5)b | 21.3 (17.5)b |

N = 67–72;

N = 30–33

N = 15–17;

N = 21–22;

latency in seconds;

z-scores;

proportion of positive and neutral facial and vocal minus negative;

9-point scale;

5-point scale. Values with different subscripts are significantly different from each other.

Conflict EF

For two of the tasks – day/night and tapping, the percentage of correct responses across all test trials was calculated. In addition, the number of practice trials was recorded. A composite score of the percent correct and number of practice trials (reversed) was calculated, such that higher scores reflected better performance. Because the three pegs task was scored as either pass or fail but had several instruction trials, children were given a 0 if they failed the task, 1 if they required two repeated instructions, 2 if they required one additional instruction, and 3 if they performed the task after the first demonstration. Thus, a high score reflected better performance on the three pegs task. A Conflict EF composite was created by averaging the z-scores of the three executive function variables (see Table 1). Group differences were revealed for the tapping task only, F (2,65) = 4.16, p < .02. Inhibited children were significantly less likely to make errors than either exuberant or low reactive children.

Emotion self-regulation

Children’s facial and vocal expressions of affect were coded from the videotaped disappointment paradigm. Vocalizations during the experimenter present and experimenter absent conditions were transcribed and then coded for content and tone. Negative verbalizations including words such as “angry” and “sad” and positive verbalizations including such words as “happy” and “love” were noted from the transcript. In rating vocalizations from the videotapes, those that were hostile, demanding or whiney were coded as negative while vocalizations that were pleasant, cheerful or appreciative were coded as positive. Verbalizations and vocalizations were further categorized as low or high positive and low or high negative. For example, if either tone or content was positive then the vocalization was coded as low positive. If the vocalization was positive in both tone and content then it was coded as high positive. All other vocalizations were coded as neutral and typically consisted of children’s reference to, or description of, the prize. Reliability on 28% of the subjects was .91 (Cohen’s kappa).

Children’s facial expressions were coded using the Facial Action Coding System (Ekman & Friesen, 1978)) as a guide. Coders were trained to mark the onset and offset of expressions reflecting low/moderate positive, high positive, low/moderate negative, and high negative affect. Positive expressions included lip corner pull and cheek raise. Negative expressions included lip corner depress, upper lip raise, chin raise, lip tighten, lip press, lip biting, nose wrinkle, inner brow raise, and lowered brow. A more detailed description of the coding scheme can be obtained from the first author. Coders were first trained to 89% agreement, and maintained 84% agreement on 24% of the subjects.

Composite scores representing positive, neutral, and negative affect during the experimenter-present and experimenter-absent conditions were created by averaging the proportion of time children expressed positive, neutral, or negative affect facially and vocally/verbally (see Table 1 for the means and standard deviations for these variables). Because we were primarily interested in preschoolers’ ability to regulate emotional expression, we chose to focus only on affect expressed during the experimenter-present condition, since this challenged the emotion regulation system more than the experimenter absent condition. Finally, to reflect the child’s ability to regulate their disappointment we created a composite by summing the proportion of positive and neutral affect and subtracting the proportion of negative affect expressed during the experimenter present condition. No temperament group differences were revealed.

Observed Temperament

To assess child temperament, we adapted the Infant Behavior Record (Bayley, 1969) and applied it to the two 4.5-year laboratory visits. Scales (description; scoring range) included: Activity level (amount of gross body movement; 1–9), Reaction to novel persons (social responsiveness to examiners; 1–5), Positive affect (level of happiness/positive mood; 1–9), Shyness/fearfulness (degree of fear of persons, situation; 1–9), and Task persistence (degree of on-task behavior; 1–9). Two observers who had different roles during the lab visits conferred at the end of each visit, came to consensus, and then scored the child on each of the above scales. All observers were trained on the application of the scale prior to its use. The observed temperament scales were significantly correlated across the two visits (r’s ranging from .41 to .54, all p’s < .01) so composites that averaged each scale across the two visits were created (see Table 1).

Child Behavior Checklist

Mothers and fathers each completed the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 4–16 (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). An Externalizing behavior score, which included aggression and delinquent behavior (Cronbach’s α= .89), an Internalizing behavior score, which consisted of anxiety/depression, social withdrawal, and somatic problems (Cronbach’s α = .75), and a Total Problems score (Cronbach’s α = .97), were calculated from the CBCL. Mother and father reports of internalizing, externalizing, and total problem behaviors were significantly correlated, r = .33, p < .01 for internalizing, r = .39, p < .005 for externalizing, r = .64, p < .001 for total problems, and thus were combined by taking the average of the two reports (see Table 1). As expected, the two broad bands were highly related (r = .61, p < .001).3

Results

Stability of Temperament

To examine whether toddlers classified as inhibited (n = 17), low reactive (n = 22) and exuberant (n = 33) maintained the attributes that characterized their temperament style, an omnibus MANOVA was conducted on the observed temperament scales, using the 2-year temperament classifications as the grouping factor. Because sex differences in social behavior emerge in the preschool years, gender was also used as a grouping factor in the analyses.

A significant multivariate effect was found for temperament group, F (12, 122) = 1.86, p < .05. Follow-up univariate ANOVAs revealed significant differences for responsiveness to novel persons, shyness, positive affect, and task persistence. As can be seen in Table 1, exuberant children were significantly more responsive to novel persons, F (2, 66) = 4.73, p < .01, d = .61, more positive in affective tone, F (2, 66) = 5.38, p < .01, d = .83, and less shy, F (2, 66) = 6.14, p < .01, d = .90, than inhibited and low reactive children. Exuberant children also demonstrated more task persistence than inhibited children, F (2, 66) = 3.37, p < .05, d = 1.04. No multivariate main effects were found for gender or the interaction between temperament group and gender.

Thus, it appears that observed temperament across two laboratory tasks at 4.5 years was systematically related to the exuberant temperament profile at 2 years of age. On the other hand, inhibited and low reactive children were very similar on the 4.5 year observed temperament ratings.

Longitudinal Outcomes for 2-Year Temperament Types

The primary goal of the present study was to examine the behavior problem outcomes of children exhibiting inhibited, exuberant, and low reactive temperament profiles. Based on our previous research and that of others (Biederman et al., 2001; Caspi et al., 1995; Frick & Morris, 2004; Putnam & Stifter, 2005) we expected that exuberant children would be rated as exhibiting more externalizing behaviors whereas inhibited children would be rated as having more internalizing behaviors. However, we also hypothesized that high levels of effortful control would moderate this relationship, particularly for exuberant children. Toward that end, we examined the moderating effects of three measures of effortful control (delay EF, conflict EF, and emotion self-regulation) on the relationship between temperament and internalizing and externalizing behaviors. We also examined these relations with total behavior problems as the outcome measure.

In each of the following analyses, hierarchical regressions were performed to examine main effects of temperament group and each of the moderators as well as their interactions. Dummy variables were created for the temperament groups. We chose to use the exuberant group as the reference because we expected exuberant children to require more regulation than inhibited or low reactive children and because the sample size of this group was the largest of the three (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). To create the interaction term, predictor variables were centered and then multiplied. In using the exuberant group as the reference in a hierarchical regression the resulting intercept represents the mean of exuberant group and the regression coefficient for the inhibited group represents the difference in means between the exuberant and inhibited groups. Likewise, the regression coefficient for the low reactive group is the difference between the means for the exuberant and low reactive groups. The regression coefficient for the moderator illustrates the degree to which those regression coefficients depend on the value of the moderator. The “main effect” regression coefficient for the moderator tests whether the intercept (the mean of the exuberant group) depends on the moderator. The other regression interaction coefficients test whether the differences between groups depend on the moderator. If the interactions are not significant then the regression coefficients related to the inhibited-exuberant and low reactive-exuberant group differences are appropriate. If the interactions are significant those mean differences are adjusted based on the value of the moderator. These adjusted means are the least square means. To help interpret these results a table of the least square means for our three groups on the outcome variables has been added.

Because of the high number of possible interactions should gender be included in the analyses, we first examined the presence of gender differences for the self-regulatory and outcome variables using two-way ANOVAs with gender and cluster group as the independent variables. Only one significant finding emerged. A main effect for gender was revealed for emotion self-regulation during the disappointment task, F (1, 69) = 4.91, p < .03, d = .23. Girls (M = .46, SD = .20) displayed more self-regulation of emotion when the experimenter was present than boys (M = .32, SD = .30). To limit the number of analyses, we only included gender interaction terms in the regressions which used emotion self-regulation during disappointment as a moderator. When adding the two-way and three-way gender interactions to these regression analyses, however, no significant effects were revealed nor were the variances explained significantly increased. Therefore, we only report results for hypothesized interaction terms (emotion self-regulation x temperament group).

The following results are organized by outcome variable. Thus, regressions using delay EF, conflict EF, and emotion self-regulation during disappointment as the moderators with externalizing behaviors as the outcome are presented first and reported in Table 2. This is followed by the results for internalizing behaviors (Table 3), and total problem behaviors (Table 4). The least square means can be found in Table 5.

Table 2.

Multiple regression results for Externalizing Behaviors

| B | SE (B) | β | F | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| I. | 2.65* | .19 | |||

| Intercept | 14.96 | 1.56 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −4.34 | 2.16 | −0.26* | ||

| Inhibited | −5.05 | 2.45 | −0.27* | ||

| Delay EF | −2.71 | 1.28 | −0.27* | ||

| Delay EF x Low Reactive | −3.09 | 3.30 | −0.12 | ||

| Delay EF x Inhibited | −2.58 | 2.80 | −0.12 | ||

| II. | 3.98** | .25 | |||

| Intercept | 13.72 | 1.31 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −4.80 | 2.03 | −0.29* | ||

| Inhibited | −6.63 | 2.43 | −0.35** | ||

| Conflict EF | −2.55 | 0.90 | −0.35** | ||

| Conflict EF x Low Reactive | 2.54 | 2.30 | 0.15 | ||

| Conflict EF x Inhibited | −0.86 | 1.95 | −0.06 | ||

| III. | 3.17** | .21 | |||

| Intercept | 16.46 | 2.25 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | − 6.81 | 2.33 | −0.41** | ||

| Inhibited | − 9.10 | 2.55 | −0.50** | ||

| ER during Disappointment (ER) | − 4.12 | 3.63 | −0.14 | ||

| ER x Low Reactive | 16.56 | 7.92 | 0.31* | ||

| ER x Inhibited | 11.46 | 8.95 | 0.19 | ||

Note:

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 3.

Multiple regression results for Internalizing Behaviors

| B | SE (B) | β | F | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| I. | 2.42* | .17 | |||

|

|

|||||

| Intercept | 5.21 | 0.79 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −2.62 | 1.10 | −0.31* | ||

| Inhibited | −2.15 | 1.25 | −0.23+ | ||

| Delay EF | .68 | 0.65 | 0.13 | ||

| Delay EF x Low Reactive | −2.91 | 1.68 | −0.23 | ||

| Delay EF x Inhibited | −2.27 | 1.43 | −0.21 | ||

| II. | 1.55 | .12 | |||

| Intercept | 5.76 | 0.00 | |||

| Low Reactive | −2.66 | 1.11 | −0.32* | ||

| Inhibited | −2.35 | 1.33 | −0.25+ | ||

| Conflict EF | −0.59 | 0.49 | −0.16 | ||

| EF x Low Reactive | 1.02 | 1.26 | 0.12 | ||

| EF x Inhibited | 0.63 | 1.07 | 0.09 | ||

| III. | 2.67* | .19 | |||

| Intercept | 8.06 | 1.19 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −3.76 | 1.24 | −0.44** | ||

| Inhibited | −2.83 | 1.35 | −0.30* | ||

| ER during Disappointment (ER) | −4.60 | 1.93 | −0.30* | ||

| ER x Low Reactive | 8.02 | 4.20 | 0.29+ | ||

| ER x Inhibited | 3.34 | 4.74 | 0.10 | ||

Note;

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 4.

Multiple regression results for Total Problem Behaviors

| B | SE (B) | β | F | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| I. | 2.00+ | .15 | |||

|

|

|||||

| Intercept | 32.46 | 3.37 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −9.86 | 4.65 | −0.28* | ||

| Inhibited | −8.86 | 5.30 | −0.22 | ||

| Delay EF | −2.72 | 2.77 | −0.13 | ||

| Delay EF x Low Reactive | −9.70 | 7.13 | −0.18 | ||

| Delay EF x Inhibited | −9.10 | 6.04 | −0.20 | ||

| II. | 3.35** | .22 | |||

| Intercept | 31.69 | 2.82 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −10.83 | 4.37 | −0.31* | ||

| Inhibited | −12.17 | 5.22 | −0.31* | ||

| Conflict EF | −5.38 | 1.93 | −0.35** | ||

| Conflict EF x Low Reactive | 5.19 | 4.94 | 0.14 | ||

| Conflict EF x Inhibited | −0.46 | 4.19 | −0.02 | ||

| III. | 2.83* | .19 | |||

| Intercept | 39.48 | 4.81 | 0.00 | ||

| Low Reactive | −15.43 | 5.00 | −0.44** | ||

| Inhibited | −16.63 | 5.46 | −0.43** | ||

| ER during Disappointment (ER) | −13.67 | 7.79 | −0.22+ | ||

| ER x Low Reactive | 38.30 | 16.97 | 0.34* | ||

| ER x Inhibited | 28.31 | 19.17 | 0.22 | ||

Note:

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 5.

Least square means for externalizing, internalizing and total problem behavior by temperament group and moderator.

| Exuberant LSMean |

Inhibited LSMean |

Low Reactive LSMean |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Externalizing | |||

| Delay EF | 13.26a | 8.23b | 8.83bc |

| Conflict EF | 13.89a | 7.21b | 9.08bc |

| ER | 13.26a | 8.23b | 8.83bc |

| Internalizing | |||

| Delay EF | 5.69a | 3.43ab | 3.00b |

| Conflict EF | 5.80a | 3.44ab | 3.13b |

| ER | 5.89a | 3.48ab | 3.15b |

| Total Problems | |||

| Delay EF | 30.82a | 21.91ab | 20.72b |

| Conflict EF | 32.03a | 19.80b | 21.20bc |

| ER | 32.03a | 18.98b | 21.44bc |

Note: Values with different subscripts are significantly different from each another.

Externalizing Behaviors

Delay EF

To examine the moderating effect of delay EF on links between temperament and externalizing behavior, a multiple regression analysis was performed with temperament group, delay EF, and their interactions entered into the equation. As can be seen in Table 2, the model was significant; however, the interaction effects were nonsignificant. A main effect for delay EF was revealed such that preschoolers who were low in delay EF were more likely to exhibit externalizing behaviors than those who were high in delay EF. In addition a main effect for temperament group showed that exuberant children were rated as higher in externalizing behaviors (M = 13.3, SD = 7.8) than either inhibited (M = 7.2, SD = 4.8) or low reactive children, (M = 9.1, SD = 8.5).

Conflict EF

Conflict EF did not moderate temperament group to predict externalizing behaviors in preschoolers (see Table 2). However, the overall model was significant with main effects for temperament group and conflict EF. As with the above model, exuberance in toddlers contributed significantly to predicting externalizing behavior. In addition, children who scored low in conflict EF were rated as high in externalizing behavior.

Emotion self-regulation

As can be seen in Table 2, the model predicting externalizing behaviors from temperament and self-regulation of emotion expression during disappointment was significant. A main effect for temperament group indicates that exuberant children were more likely to be rated has having externalizing behaviors than either inhibited or low reactive children. This effect, however, was subsumed under a significant interaction effect for temperament group and emotion regulation. Although the interaction suggests that exuberant toddlers who exhibited lower emotion-self-regulation were more likely to be rated as high in externalizing behaviors, a follow-up analysis that tested the overall interaction (whether the interactions were different from zero), however, was not significant (p = .11).

Internalizing Behaviors

Delay EF

The regression model assessing the moderating effect of delay EF on internalizing behavior was significant and revealed a main effect for temperament group (see Table 3). Exuberant children were rated by their parents as higher in internalizing behaviors (M = 5.6, SD = 4.6) than low reactive children (M = 3.1, SD = 3.0). Contrary to expectation, there was a tendency for exuberant children to be rated higher than inhibited children (M = 3.9, SD = 3.6). The difference between the inhibited and low reactive groups was nonsignificant. No other main or interactions effects were found.

Conflict EF

As can be seen in Table 3, the model for predicting internalizing behaviors from temperament group, conflict EF, and their interaction was not significant although the above finding that exuberant children were more internalizing than low reactive and inhibited children was supported by this model.

Emotion self-regulation

The model examining self-regulation of emotion during disappointment as a moderator of temperament group in predicting internalizing behavior was significant (see Table 3). A significant effect for temperament group confirmed exuberant children to exhibit more internalizing behaviors than either inhibited or low reactive children. In addition, a significant effect for emotion self-regulation was revealed. Children who were able to express more positive or neutral affect during the experimenter present condition of the disappointment task were less likely to be rated as internalizing than children who had difficulty regulating their emotions.

Total Problem Behaviors

Delay EF

A near significant model predicting total behavior problems was found with delay EF as the moderator (see Table 4). Only temperament group was a significant predictor. Exuberant toddlers were more likely to be rated as having more problem behaviors as preschoolers (M = 30.7, SD = 17.0) than low reactive toddlers (M = 21.3, SD = 17.5).

Conflict EF

The model examining the prediction of total problem behavior with conflict EF as the moderator was significant. As can be seen in Table 4 two main effects were revealed. In this model, both low reactive and inhibited children had fewer total behavior problems than exuberant children (see Table 5). And, children who were lower in conflict EF were more likely to present with problem behaviors than children scoring high on the executive function tasks.

Emotion self-regulation

The model predicting total problem behavior with emotion self-regulation as the moderator was significant (see Table 4). A significant main effect for temperament group confirms that exuberant toddlers presented with more total behavior problems as preschoolers than either low reactive or inhibited toddlers. A significant interaction effect was also revealed for the moderator of emotion regulation. A test of the overall interaction approached significance (p = .08).

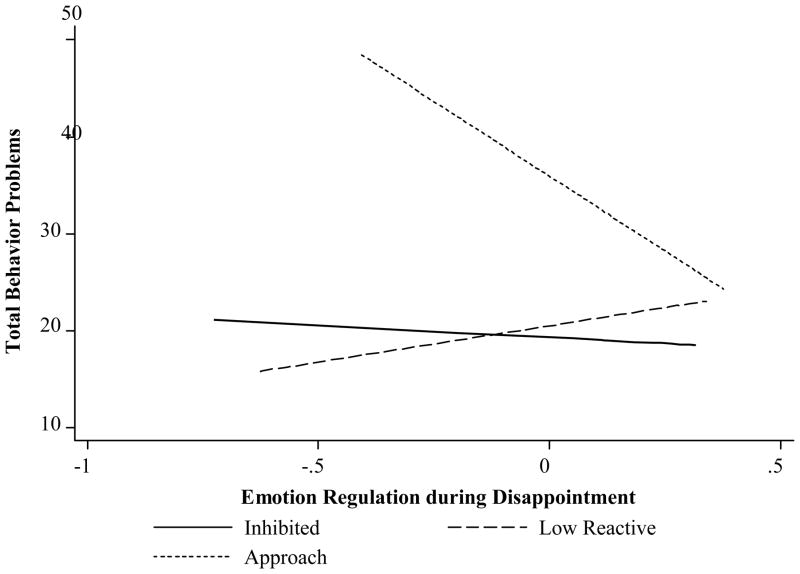

Because we had hypothesized that emotion regulation would moderate problem behavior for exuberant children, in particular, and the same interaction was significant for externalizing behaviors, we plotted the interaction and tested for significant slopes. Figure 1 illustrates the interaction between temperament group and emotion self-regulation for total problem behaviors. A test of simple slopes revealed that regulation of emotion during disappointment decreased the presence of preschool problem behaviors for exuberant children, b = −.30.8, t (59) = −2.39, p < .05, while it had no effect on either the inhibited, b = −2.51, t (59) = −.18, ns, or low reactive children, b = 7.49, t (59) = .69, ns.4

Figure 1.

Relationship between emotion regulation during disappointment and total problem behaviors for each temperament group.

Discussion

The first goal of the present study was to investigate the stability of the inhibited and exuberant temperament profiles. The second goal was to assess the prediction from temperament to risk for problem behaviors and test whether effortful control moderated this relationship. Our findings supported our hypotheses that exuberance would be a stable characteristic and that children classified as exuberant as toddlers would be at greatest risk for preschool problem behavior, particularly if they lacked emotion self-regulatory skills.

Using temperament groups (inhibited, exuberant, low reactive) created through cluster analysis when participants were 2 years of age, we found moderate stability, but only for exuberance. Exuberant toddlers continued to show interest in novel persons and to show high levels of positive affect. In addition, they were observed to be less shy than both inhibited and low reactive children. These findings are consistent with previous reports (Fox et al., 2001; Pfeifer et al., 2002) of stability of exuberance from the toddler through the preschool period. What is important about the present findings is that the situations and measures used to assess these behaviors were different at the two assessment points, indicating cross-contextual as well as longitudinal stability. At 2 years of age, inhibition and exuberance were assessed when engaging in “risk room” activities including interacting with strangers and participating in high intensity activities. Such tasks were designed to pull for approach/inhibition and the emotions that would be expected to accompany such tasks. Aside from the laboratory setting and a new set of strangers, the 4.5-year visit was not specifically designed for assessing approach/inhibition. Nevertheless, at the minimum, exuberant toddlers behaved in ways to suggest some stability of their temperament style two and one-half years later.

In contrast, inhibited toddlers did not show significant stability. While they were shyer and less responsive to the examiner than exuberant toddlers, their behavior was not distinguished from that of the low reactive children. This finding is consistent with previous research examining the longitudinal stability of inhibited children. Although stability was revealed for inhibition, particularly for those at the extreme end (Kagan, 1994; Pfeifer et al., 2002), there was still “lawful discontinuity” (Belsky & Pensky, 1988) for a significant proportion of these children, such as those in day care, or with less than sensitive parents (Fox et al., 2001; Park et al., 1997). It may be that the preschool child’s ever expanding social world and the pressures to interact with other children and adults encourages inhibited children to act in ways that are inconsistent with their temperament. Cross-cultural research suggests that Western societies are less tolerant of inhibited behavior in children than Eastern societies such as China (Chen et al., 1998), so these pressures may be particularly salient for U.S. children. Children in the present study were familiar with the laboratory setting and thus, may not have felt the uncertainty of being in a more novel situation. In addition, the 4.5 year tasks were not designed to evoke high levels of fear/shyness. The fact that the children, who were tested over two years later, likely had little memory of their previous visits and were engaged in tasks with an unfamiliar female adult does not support this explanation.

The second goal of the present study was to test the predictive relationship between 2 year temperament and preschool problem behavior. We also examined whether the development of effortful control would moderate this relationship. In the present study we examined three forms of effortful control: (1) the ability to suppress/delay responses to reward; (2) the ability to produce a novel response while suppressing a dominant response; and (3) the ability to regulate emotion during a disappointment task. As expected, exuberant toddlers were more likely to be rated by their parents as exhibiting high levels of externalizing and total problem behaviors than inhibited or low reactive toddlers. These findings add to the growing literature that exuberant or highly surgent children may be at risk for developing problem behaviors, particularly of the externalizing type. In addition, they confirm our earlier cross-sectional finding that exuberant toddlers were more likely to be rated as externalizing and that this link between temperament and externalizing did not merely reflect a developmental phase (Putnam & Stifter, 2005).

As children develop and their social world opens up, they are increasingly confronted with rules and standards for behavior (Gralinski & Kopp, 1993). For exuberant children, these may represent very difficult developmental tasks as they are predisposed toward approaching, often impulsively, new and exciting people and situations. Consequently, limits on their temperamental style may lead to frustration and aggressive, defiant behavior. However, as hypothesized, if they develop effortful control, their risk of developing externalizing behaviors should be reduced. Our findings suggest that this may be true for the ability to self-regulate emotion.

When considering the relative presence of positive, neutral and negative affective expressions during disappointment, the results suggest that expressing less positive/neutral and more negative emotion expressions when receiving an unwanted gift increased the risk of externalizing and total problem behaviors for exuberant children. That is, under conditions in which preschoolers are expected to exhibit positive or neutral affect in the presence of a gift-giving adult exuberant children who ‘leaked” their frustration when disappointed were rated by their parents as having higher levels of problem behaviors than those exuberant children who could modulate their feelings and expressions. This result is consistent with previous studies of children’s reactions to disappointment which have found that exhibiting high levels of negative emotion, anger specifically, when the experimenter was present were related to more externalizing behaviors such as aggression (Bohnert, Crnic, & Lim, 2003; Cole, Zahn-Waxler, & Smith, 1994; Liew, Eisenberg, & Reiser, 2004). That our findings should suggest this dysregulated affective response for the exuberant child who is characterized by high intensity pleasure is intriguing. Understanding children’s orientation toward reward and their reactions to receiving an unwanted gift, however, may be a step toward interpreting this finding.

In the adult personality literature, individuals who are high on approach, positive affect, and impulsivity are also more sensitive to reward (Cloninger, 1987; Gray, 1982). These characteristics have been applied to child temperament (e.g., surgency; Rothbart et al., 2000) as well as child psychopathology (Quay, 1988). Likewise, frustration and aggression have been associated with approach and attention to reward in both adults (Carver, 2004; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997) and children (Fox & Davidson, 1988; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994) Exuberant children in the present study may have been exceptionally focused on the possibility of a reward that when unfulfilled resulted in frustration. It may also be that without regulatory skills they could not draw upon their positive predisposition to counteract these feelings. Thus, if an exuberant child, who confronts more limitations than other children, has not developed effective means for dealing with the frustration and anger that results, then he or she may be at higher risk for problem behavior, above and beyond that associated with their temperamental disposition. It is important to note that we assumed that children who showed more positive/neutral expressions during the experimenter present condition were regulating their disappointment as well as their expression (Cole et al., 2004). There is sufficient evidence both in the present study and from previous studies that the majority of children were upset about not receiving the preferred gift (e.g., more negative affect expressed during the experimenter absent condition, desired the exchange of the disappointing gift for preferred gift, expressed disappointment to both the parent and experimenter), however, for some children receiving the lowest ranked gift may have not been as disappointing and thus their low levels of negative affect resulted from indifference. Future research should examine other incidences of self-regulation of emotion to confirm the present finding of a moderating role of emotion regulation in the association between temperament and behavior problems.

Contrary to our expectations, our results also revealed exuberant children, rather than inhibited children, to be rated as higher in internalizing behaviors. Co-morbidity of dimensional or categorical indices of internalizing and externalizing behaviors is common in community samples (see Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999). A recent study utilizing latent growth modeling found increases in externalizing behaviors to coincide with increases in internalizing problems across the preschool period (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). Shared modes of assessment or shared diagnostic criteria are possible methodological explanations for the co-variance between internalizing and externalizing, however, the commonality of this co-variation in community samples suggests that substantive sources may be more explanatory (Lillenfeld, 2003). For example, one disorder may predispose another (Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003; Lillenfeld, 2003). Gilliom and Shaw (2004) demonstrated that increases in internalizing behaviors in preschool children were initiated by high levels of early externalizing behavior. A second substantive explanation for co-morbidity may be a shared causal source such as temperament. Interestingly, negative emotionality has been related to high levels of both dimensions within a sample (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004; Keiley et al., 2003). Although exuberant children are characterized by high intensity positive affect, they are also likely to become frustrated when goals are blocked. In the present study, exhibiting greater negative affect during the disappointment task was directly related to internalizing while increasing the risk of problem behaviors for exuberant children.

A third explanation comes from the self regulation model proposed by Carver and Sheier (Carver & Sheier, 1998). In this model, anger, an externalizing emotion, may result when progress toward a goal (approach) is inadequate thus functioning to increase efforts to overcome the obstacle. However, if persistent effort toward the goal does not produce adequate progress then sadness/depression, an internalizing emotion, may result. Thus, exuberant children who are motivated by approach toward rewards may also develop internalizing behaviors when rewards appear unobtainable. Because our sample was drawn from the community these interpretations should be treated with caution. Future research might consider extreme groups of exuberant and inhibited children to confirm the potential risks of certain temperament profiles for clinical levels of problem behavior. Understanding the source of co-variance between internalizing and externalizing and specifying they type of internalizing problem is particularly important, as there is evidence that internalizing in conjunction with externalizing can either increase or decrease the risk for future delinquent behavior depending upon whether depression or anxiety is present (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003).

While they did not moderate the relationship between temperament and risk for problem behavior, measures of delay EF and conflict EF were found to have direct links to preschool externalizing behaviors and total problem behaviors. In light of the literature that aggressive and oppositional defiant children are lacking in cognitive regulatory skills, these findings are not surprising. For example, Eisenberg and colleagues have demonstrated low levels of effortful control to be directly related to externalizing behaviors both concurrently and longitudinally (Eisenberg et al., 2004). Likewise, poorer performance on executive function tasks has been linked to externalizing behaviors in preschoolers and adolescents (Giancola, 1995; Hughes et al., 2000; Moffit, 1993). Difficulties with effortful control may impair the child’s ability to formulate alternative strategies to dealing with events that are emotionally evocative, regardless of their temperamental predisposition to respond with a particular emotion. Conversely, the ability to inhibit/delay a dominant response and/or to perform a subdominant response according to the demands of the environment may override any temperamental differences that would protect the child from developing problem behaviors (e.g., inhibition – see Schwartz et al., 1996).

Finally, dysregulated affect expressions during the disappointment task when the experimenter was present were associated with internalizing behaviors. As mentioned previously, studies of disappointment have demonstrated that the inability to control emotional reactions to disappointment was predictive of externalizing, not internalizing, types of behavior. Thus, the present finding is not consistent with the previous literature. Differences in the samples may account for the contrasting findings. Many of the prior studies were conducted with children already presenting with problem behavior, whereas children in the present study were drawn from the community and differentiated by their temperamental predispositions. In one study with a normative sample of fourth graders (McDowell, O’Neill, & Parke, 2000), the finding that children who expressed more negative affect during disappointment were rated by their peers as more sad, disliked and lonely is somewhat consistent with our results. It may be necessary in future research with both clinical and community samples to assess discrete emotion expressions to clarify the role of negative affect during disappointment in predicting problem behaviors. For example, of the children who expressed negative affect, some may have felt anger at receiving the non-preferred gift while others may have felt sadness.

In drawing conclusions from our findings, we were confronted with several limitations that may inform future research. For example, although we were careful not to use the terminology “internalizing and externalizing problems,” we recognize that the risk we identified may only be for high levels of temperament-related behaviors, rather than problem behaviors. Future research may want to take the extreme group approach used previously to understand the mental health outcomes of extremely uninhibited children to clarify whether dysregulated affect is a risk for exuberant toddlers. Likewise, we did not measure parenting behaviors, which we note may have an important role in moderating exuberant behavior. For example, Kochanska (Kochanska, 1997) has shown that mothers who demonstrate high levels of shared positive affect may influence their fearless children to be more compliant and conscientious. Finally, our sample was small and low risk (white, middle class) and thus caution should be taken in generalizing our findings. It would be interesting to examine these same factors in a low-income sample where exuberant toddlers may be presented with greater challenges.

In summary, the present study partially confirmed the relative stability of temperament while also demonstrating the moderating role of emotion self-regulation in predicting preschool externalizing and total problem behavior. Exuberant toddlers, particularly those who expressed more negative affect during the disappointment task, were more likely to be rated as having problem behaviors as preschoolers. Surprisingly, exuberant children were rated as high in internalizing behaviors, as well. These findings suggest that exuberant children, while exhibiting very positive, socially outgoing behaviors, may also be prone to developing maladaptive or socially inappropriate behaviors. Children who are interested and engaged by the world around them have many opportunities to become frustrated, particularly as they encounter increasing attempts by parents, caregivers, and teachers to establish rules of conduct that limit children’s behaviors. These early and frequent confrontations provide important contexts for developing and learning regulatory strategies. However, if the exuberant child cannot adjust his or her behavior, specifically their emotions, accordingly, they may resort to less effective means of getting what they want and develop more internalizing emotions. Capitalizing on the exuberant children’s positivity, such as responding to them, in kind, may help them to “undo” the negative emotions (Fredrickson, 2001) they may feel when frustrated, putting them on a positive developmental trajectory.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant to the first author from the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH#50843). We want to thank the families who participated in the Emotional Beginnings Project.

Footnotes

The original sample was designed to follow children from 2 weeks of age until 2 years of age. Families were re-contacted when the target child was 4 years old to participate in a follow-up study. A significant number of families had moved out of town by that time while others were not able to commit to another longitudinal study.

Based on Carlson and Moses’ (2001) finding that inhibitory control factors into delay and conflict components, a principal components analysis was used to explore the coherence of the delay of gratification, dinky toys, day/night, tapping, and 3 pegs tasks. The results revealed two factors (eigenvalues = 1.7 and 1.1) with day/night (.66), tapping (.84) and 3 pegs (.53) loading on the first factor and the delay of gratification (.46) and dinky toys (.88) loading on the second factor.

T-scores were calculated for each subject and borderline cut-offs for externalizing, internalizing, and total problem behaviors used to determine the presence of significant problem behaviors in the three temperament groups. Only 3 children (2 exuberant, 1 low reactive) were above the cut-off of 67 for externalizing (χ2 == n.s.) and 6 children (4 exuberant, 1 low reactive, 1 inhibited) were above the cut-off for internalizing (χ2 = n.s.). However, 9 children were above the borderline clinical cut-off of 60 for total problem behavior with exuberant children (N = 7) more likely to be rated as having more problem behaviors, χ2 (2) = 4.60, p < .10, than low reactive (N = 1) or inhibited (N = 1) children.

Simple slopes were also calculated for externalizing behaviors. The slope for exuberant children showed a near significant decreasing trend, b = −11.38, t (59) = −1.89, p = .06, whereas the slopes for the inhibited group, b = .08, t (59) = .01, p = .99, and the low reactive group, b = 5.19, t (59) = −1.01, p = .32, were not significant. Exuberant children who showed high levels of positive/neutral affect during disappointment were less likely to be rated as externalizing than those who exhibited relatively more negative affect.

Contributor Information

Cynthia S. Stifter, The Pennsylvania State University

Samuel Putnam, Bowdoin College.

Laudan Jahromi, University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS, Howell CT. Empirically based assessment of the behavioral/emotional problems of 2-and 3-year-old children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15:629–650. doi: 10.1007/BF00917246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello J, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf J. Development of inhibition during childhood: Evidence for situational specificity and a two-factor model. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:721–730. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf J. The malleability of behavioral inhibition: A study of individual developmental functions. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:912–919. [Google Scholar]

- Balamore U, Wozniak RH. Speech-action coordination in young children. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:850–858. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pensky E. Marital change across the transition to parenthood. Marriage and Family Review. 1988;12:133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker D, Rosenbaum J, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A, Crnic K, Lim K. Emotional competence and aggressive behavior in school-age children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:79–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1021725400321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE. Physiological and behavioral regulation in two-year-old children with aggressive/destructive behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(2):103–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005112912906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson S, Moses L. Individual differences in inhibitory control and theory of mind. Child Development. 2001;(72):1032–1053. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. Negative affects deriving from the behavioral approach system. Emotion. 2004;4:3–22. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C, Sheier M. On the self regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Henry B, McGee R, Moffit T, Silva P. Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: From age three to eighteen. Child Development. 1995;66:55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hastings P, Rubin K, Chen H, Cen GSS. Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in chinese and canadian toddlers: A cross-cultural study. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:677–686. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cohen D. Perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental psychopathology Vol. 1: Theory and Methods. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger RC. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:523–540. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Colder C, O’Connor R. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity model and child psychopathology: Laboratory and questionnaire assessment of the bas and bis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:435–451. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030296.54122.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole P. Children’s spontaneous control of facial expressions. Child Development. 1986;57:1309–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Cole P, Zahn-Waxler C, Smith D. Expressive control during a disappointment: Variations related to preschoolers’ behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75(2):317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Taylor C. Development of an aspect of executive control: Development of the abilities to remember what i said and to “do as i say, not as i do”. Developmental Psychobiology. 1996;29:315–334. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199605)29:4<315::AID-DEV2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes R, Gutherie I, Murphy B, Maszk P, Holmgren R, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]