Abstract

Intermolecular multiple-quantum coherences (iMQCs) can generate NMR signals from exceedingly small dipolar interactions between distant spins in solutions. In the last few years, these signals have been used for a wide range of applications in imaging and high-resolution spectroscopy. Recent applications include MRI contrast enhancement, suppression of inhomogeneous broadening in NMR experiments, and more recently, in vivo temperature measurement. In this chapter, we describe how basic iMQC pulse sequences work and how to select the sequence parameters to optimize iMQC signals and to overcome signal contamination.

Keywords: Dipolar field, intermolecular multiple-quantum coherences, correlation gradient, correlation distance

1. Introduction

iMQCs arise from simultaneous spin flips on distant molecules in a solution. Specifically, a resonance corresponding to raising the spin state of a proton on a macromolecule and simultaneously lowering the spin state of a proton in its aqueous solvent is called “intermolecular zero-quantum coherence” or iZQC, because the net number of spin flips (one up, one down) is zero. A resonance corresponding to two simultaneous upward spin flips is called a + double-quantum coherence (iDQC) and a resonance corresponding to two simultaneous downward spin flips is called a − double-quantum coherence. The conventional theoretical framework of NMR predicts that signals from such transitions are impossible to observe. Indeed, they were not evident in the early days of low-field magnetic resonance. Over the last few years, with the increase in magnetic field strengths, iMQC signals nearly as large as the conventional magnetization signals have been detected (1-5). This is because the detection of these signals is made possible by the long-range dipolar interaction, which is proportional to the magnetic field strength (6, 7). This interaction can be ignored even in high magnetic field strength if the magnetization is isotropic, but if the isotropy is broken with odd-shaped samples or gradient pulses, the dipole-dipole coupling can increase to produce noticeable effects.

In the last few years, iMQCs have progressed from academic curiosities into wide usage in imaging and high-resolution spectroscopy. Recent applications include contrast enhancement in magnetic resonance imaging (8-10), functional imaging (11-14), suppression of inhomogeneous broadening (15-17), measurements of local magnetization structure (18, 19), and more recently, measurements of temperature in vivo (20).

The iMQC signal is proportional to the local dipolar field at the correlation distance, dc = 1/(γ GT), that can be tuned by changing the strength GT of the magnetic field gradient pulses used in the iMQC experiments. This distance is usually chosen to be smaller than the typical voxel size, between tens and hundred of micrometers, making the iMQC signal intrinsically sensitive to local dipolar field, altering magnetization and susceptibility structure over sub-voxel distances.

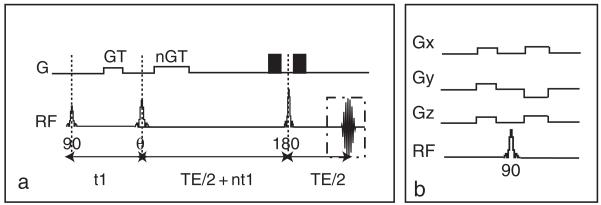

The prototype iMQC pulse sequence is the “CRAZED” (correlated spectroscopy revamped by asymmetric z-gradient echo detection) (5) sequence, shown in Fig. 1. The CRAZED pulse sequence is similar to a COSY [COrrelation SpectroscopY] sequence, but differs in that the second CRAZED RF pulse is bracketed by two magnetic field gradient pulses, the correlation gradient pulses, with amplitude G and length T, used to select the signal from a specific order of coherence (iDQC, iZQC, etc.). These gradient pulses break the spatial isotropy and preserve the dipolar field interactions which are not averaged out by molecular diffusion at large separation, and which are responsible for the refocusing of transverse magnetization during the final time period t2 (6). The refocusing rate of the signal during t2 is 1/τd, where τd = (γμ0M0)−1. τd is the dipolar demagnetization time and depends on the strength of the dipolar field, which, for this sequence, modulates the magnetization along a well-defined direction and is directly proportional to the local longitudinal magnetization (7). For standard samples in standard magnetic field gradients, the refocusing is very slow (hundreds of milliseconds) and the signal usually relaxes before a complete refocusing (21). In other words, the refocusing is partially hampered by the transverse relaxation time, rendering the available signal much smaller than its theoretical value. For this reason, it is particularly important to optimize the parameters of a CRAZED sequence to yield maximum image contrast over a noisy background signal. The reduced signal also makes such sequences very sensitive to interference by signals that follow alternate coherence pathways. It is therefore necessary to simultaneously adopt experimental sequence modifications, such as phase cycling to eliminate undesired coherences while preserving the dipolar coupling signal.

Fig. 1.

(a) Standard CRAZED pulse sequence used to observe iMQC signal. The first RF pulse (90°), which excites the equilibrium magnetization, is followed by a delay t1 during which a gradient pulse of strength G and duration T, dephasing the transverse magnetization, is applied. A second RF pulse θ transfers part of this modulated magnetization along the z-axis creating the correct dipolar field to refocus the transverse magnetization. The ratio (nGT)/(GT) determines the selected coherence order. A third RF pulse (180°), at a time TE/2 + nt1 after the second RF pulse, is used to refocus inhomogeneous broadening during the evolution time t2 and allow the refocusing of the iMQC signal at TE/2 after the pulse. (b) Crusher module used to suppress signal contamination from stimulated echoes when the magnetization is not completely allowed to relax toward thermal equilibrium between scans. The 90° pulse is surrounded by crusher gradients along the magic angle. The combination of the gradients and the broadband 90° pulse dephases both the transverse and the longitudinal magnetization. The crusher module is usually put at the end of the sequence, provided that dummy scans are performed as well.

Below, we explain how to perform a standard iDQC experiment and how to select all the parameters in a CRAZED pulse sequence.

2. Materials

A high-field superconductive magnet.

Shim gradient coils.

Imaging gradient coils.

A scanner equipped with a radio frequency (RF) synthesizer and a power amplifier.

A 1H transmitter and receiver coil.

A sample tube filled with 1% agarose, 0.5% Magnevist, and 10 Mm isopropanol containing some structured sample (in our case, Legos).

A pulse program for the CRAZED sequence (see Note 1).

3. Methods

Position the sample in the center of the RF coil and in the center of the magnet.

Connect the coil to the preamplifier.

Match and tune the RF coil.

Shim the magnetic field using the first- and second-order shims.

Find the resonance frequency and select it as the basic transmitter and receiver frequency.

Calibrate the RF pulses.

Run a preliminary scan to see if the sample is positioned correctly in the center of the magnet.

- Select the CRAZED sequence parameters, RF pulses, gradient pulses, and delays as follows:

- Select the first RF pulse to be a BIR-4 pulse with a 90° flip angle and with 1 ms duration (see Note 2).

- Select the second RF pulse to be a BIR-4 pulse with a 120° flip angle and with 1 ms duration (see Note 3).

- Select the two refocusing pulses to be adiabatic full passage hyperbolic secant refocusing pulses with 4 ms duration (see Note 4).

- Select an axial slice with 2 mm thickness.

- Select the direction of the correlation gradient along the z-direction (Gc = Gz)

- Select the strength of both the correlation gradient pulses to be 12 G/cm (this will select a correlation distance of 90 μm) (see Note 5).

- Select the duration of the first gradient pulse to 1 ms and the duration of the second gradient pulse to 2 ms (see Note 6).

- Select the crusher gradients around the refocusing pulses along the z-direction with a strength of 15 G/cm strength and a duration of 1 ms (see Note 7).

- Select the following delays between the pulses: 90–120°, 2.5 ms; 120–180°, 15 ms; 180–180°, 20 ms; 180° center acquisition window, 10 ms (see Note 8).

- Select a field of view of 40 mm and a matrix size of 128 × 128 so that the in-plane spatial resolution is about 300 μm/pixel (see Note 9).

- Select a repetition time of 5 s.

- Fourier transform the acquired data.

Repeat the same experiment while changing the direction of the correlation gradient along the x-direction.

Repeat the same experiment while changing the direction of the correlation gradient along the y-direction.

Subtract the magnitude of the images |Gz| – |Gx| – |Gy| to resolve the magnetization density anisotropy map (Fig. 2) (see Note 12).

Repeat the same experiment by using correlation gradients along the z-direction with strengths of 4.2 G/cm and 25 G/cm, and subtract the magnitude of the images (Fig. 3).

Acquire an image using the standard SPIN-ECHO sequence available on the scanner with an echo time of 45 ms, using the same image parameters used in the previous experiments (see Note 13).

Compare the spin-echo image with the iDQC image (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

iDQC images acquired with a correlation distance of 90 μm selected along the x-(a), y-(b) and z-(c) directions (images with the same intensity scale). The signal intensity of the images acquired with the correlation gradient along the x- and y- directions is half that of the image acquired with the correlation gradient along the z-direction. The subtraction image (|Gz | − |Gx | − |Gy |) highlights the structural features of the imaged sample (d).

Fig. 3.

iDQC images acquired with the correlation gradient along the z-direction, at two different strengths: Gc = 25 G/cm (b) to select a correlation distance of 47 μm; and Gc = 4 G/cm (a) to select a correlation distance of 280 μm. The subtraction image (c) shows bigger intensity overall for the image acquired with smaller correlation gradients (due to a smaller diffusion attenuation) and a different contrast when the correlation gradient is comparable to structural sample features (arrow in c).

Fig. 4.

Comparison between the iDQC image with Gc = Gz = 12 G/cm (a) and a spin-echo image (b) of the same phantom acquired with the same echo time.

Fig. 5.

Acquisition window for an iDQC CRAZED sequence selecting a weak correlation gradient (Gc = 4 G/cm) along the read encoding direction. When the correlation gradient is selected along one of the image-encoding directions and the correlation distance is comparable to the image resolution (in this case dc = 280 μm and the image resolution is 300 μm), the correlation gradient couples with the encoding gradients and produces spurious echoes in the acquisition window (see arrows) and banding artifacts in the acquired image.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the real (a) and imaginary (b) parts of the signals obtained from the iDQC CRAZED sequence, selecting the correlation gradient along the z- or x-direction (Gc = Gx and Gc = Gz). With respect to the signal obtained with Gc = Gx, the signal obtained with Gc = Gz is twice as strong and with an opposite phase. If the correlation gradient is chosen along the direction of the magic angle (Gz = Gx = Gy), the iDQC signal disappears (c).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant EB 02122.

Footnotes

The CRAZED sequence is typically not available on commercial spectrometers and must therefore be programmed by the user. The sequence is relatively simple and is illustrated in Fig. 1a. The main components are the three RF pulses and the two magnetic field gradient pulses. The correct selection of the sequence delays and the RF and gradient pulses is very important for signal optimization. Bad sequence parameter choice can drastically reduce image SNR and/or produce strong signal contaminations.

The first RF pulse is 90° and is intended to excite all the spins in the sample. Therefore, it is a broadband pulse. The pulse shape can be that of a standard amplitude-modulated pulse, like a Hermitian, sinc, or Gaussian pulse. A superior excitation is achieved through the use of adiabatic pulses that ensure uniform sample excitation, such as the adiabatic half passage pulse (AHP) or the B1-insentitive rotation (BIR-4) pulse. For imaging experiments, this pulse is not slice selective to produce a modulation of the magnetization in the entire sample.

The second pulse, also called the mixing pulse, is used to map a portion of the modulated magnetization onto the z-axis. This modulated Mz magnetization will eventually produce the dipolar field necessary to refocus the transverse magnetization. This pulse, along with the first excitation pulse, is non slice-selective: uniform modulation has to be created throughout the sample. A simple broadband amplitude-modulated pulse achieves this aim. For optimal uniformity, an adiabatic pulse should be used.

The flip angle of the second RF pulse typically determines the strength of the signal. The optimal flip angles are 60, 120, and 45 or 135° for the selection of the +iDQC, −iDQC, and iZQC signals, respectively.

In order to maximize CRAZED signal intensity, a spin-echo type acquisition of the DQC signal is usually performed. The refocusing pulse rephases inhomogeneous broadening of the signal during t2 evolution. In imaging experiments, this is the only slice-selective pulse in the sequence. It can either be a standard amplitude-modulated pulse or an adiabatic pulse. For an adiabatic pulse such as a hyperbolic secant pulse, the spin-echo pulse should be always accompanied by another identical 180° slice-selective pulse to prevent phase rolling across the image. The phase roll in this case come from temporal inversion offset of spins with different resonance frequencies, so that the symmetry of refocusing experiments is perturbed by appreciable amounts (milliseconds), and a serious phase dispersion is introduced.

The 180° pulse is usually flanked by crusher gradients, whose amplitude is usually different from that of the correlation gradient to preclude the refocusing of spurious signals. The crusher is usually applied along the three orthogonal directions (x, y and z) to crash unwanted magnetization that is not refocused by the pulse.

The gradient pulse is used to reintroduce the effect of the dipolar field through spatial modulation of the sample magnetization. The sinusoidal modulation produced by the magnetic field gradient produces a strong dipolar field between spins, which are a pitch, or a correlation distance, apart. Both the direction and the strength of the correlation distance, chosen to select a correlation distance between 30 and 500 μm for imaging experiments, affect the image contrast in structured samples. If the correlation distance is too small, the modulation can be easily wiped out by spin diffusion, while if too long, spurious signals can easily contaminate image contrast. Some of these spurious signals can easily be spotted during image acquisition, since they appear as extra time-shifted echoes (Fig. 5).

The second gradient pulse should have an area which is n times the area of the first gradient pulse to select the nth-order iMQC coherence. For example, the +DQC requires a 2GT gradient, a −DQC a −2GT gradient, and a ZQC no gradient. To overcome gradient non-linearity, n gradient pulses identical to the first pulse can be applied. The position of the second correlation gradient pulse is usually as close as possible to the mixing pulse, to minimize signal attenuation due to diffusion (Fig. 3).

A crusher module can be applied at the beginning of the sequence, before the scan–scan pad time, to prevent signal contamination by stimulated echoes. This contamination is a serious problem especially when a very short repetition time is used. The crusher module consists of a 90° pulse sandwiched between a pair of two different gradient pulses oriented along the magic angle (x, y, and z all positive for the first pulse; x inverted for the second pulse) at the beginning of the scan as shown in Fig. 1b.

Pulse sequencing time delays have a strong effect on signal optimization and the image contrast. IMQC signal evolves during the first delay between the excitation and the mixing pulses. This delay is usually chosen to be few milliseconds to overcome losses due to transverse relaxation, which in the case of iMQC is faster than the standard transverse spin relaxation. Longer delays are usually applied to highlight T2 inhomogeneities in the sample. In general, the gradient pulse is moved closer to the mixing pulse and a padding time between the end of the gradient pulse and the mixing pulse is used to avoid leakage of the gradient during the pulses.

The second pulse field gradient is initiated close after the mixing pulse to minimize diffusion attenuation of the signal. The position of the refocusing pulse is usually TE/2 + nt after the mixing pulse, which leads to the refocusing of the signal at TE/2 after the refocusing pulse.

The total echo time TE + nt is usually chosen to maximize the signal strength. Unlike standard NMR signal, the iMQC signal grows with time after the mixing pulse, reaches a maximum, and then decays. The maximum, in absence of relaxation, is achieved at 2.6 τd for the iZQC signal (8) and 2.2 τd for the iDQC signal (22). However, in presence of relaxation, the maximum is shifted toward smaller t2 (21). A good approximation, in this case, is that t2 ~ T2 in the sample (23).

Special attention must be placed on selecting the image resolution, especially if the correlation gradient has been selected along one of the image-encoding directions. In this case, if the voxel size is comparable to the correlation distance, spurious echoes will be refocused in the acquisition window (Fig. 5) which will produce banding artifacts in the image.

The sequence can use a Cartesian acquisition scheme or an echo-planar imaging (EPI) acquisition scheme. The EPI acquisition scheme, although much faster than the single line scheme, usually introduces artifacts in reconstructed images, including geometric distortion and ghosting due to a variety of sources, including off resonance, in-plane flow, and echo misalignment.

Usually, a phase cycle is used to suppress unwanted signals from different coherent pathways. For +/− DQC signal, a four-step phase-cycling scheme is usually applied to the first excitation pulse (x, −x, y, y), while the phase of the mixing pulse, (x), is held constant. At the same time, the receiver phase is cycled (x, x, −x, −x). Excellent suppression of spurious signal contributions from unwanted coherence-transfer pathways can also be achieved with a simple two-step phase cycle, first by pulse (x, −x), and then receiver (x,x), provided the repetition time-is much longer than the longitudinal relaxation time of the spin system (TR > 5T1). For selection of the ZQC signal, the first RF pulse has to be cycled through (x, y, −x, −y), while the receiver and other pulse phases should be held constant. However, in this case, the phase cycle of the excitation pulse does not suppress unwanted coherences that are excited for the first time by the mixing pulse. In this case, to suppress the standard signal excited by the mixing pulse, the direction of the correlation gradient pulse should be alternated between z and y or x, while the receiver phase is alternated between x and −x (8).

In order to prove that the collected signal is purely iMQC, The user can simply look at the phase of the signal as the direction of the correlation gradient is changed from z to either x or y. If the signal is purely iMQC, the phase of the signal should change and the strength should be reduced more or less by half (Fig. 6a, b). Moreover if the direction of the correlation gradient is chosen along the magic angle, the signal should be considerably diminished (Fig. 6c). These few tests should be done each time a new sequence is programmed into a spectrometer.

Theoretically, the iMQC signal should comprise a large fraction of the standard SQC signal.

When relaxation is included, however, the maximum achievable signal from a typical CRAZED sequence, in the linear regime, is proportional to T2/τd. This means that for samples with a short T2, as encountered in vivo, signals from intermolecular multiple-quantum coherences (iMQCs) are greatly diminished. This makes it very difficult to perform experiments on regions with T2 on the order of few milliseconds (liver tissue, for example) unless τd is decreased by hyperpolarizing the sample.

References

- 1.Deville G, Bernier M, Delrieux JM. NMR multiple echoes observed in solid He-3. Phys. Rev. B. 1979;19:5666. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einzel D, Eska G, Hirayoshi Y, Kopp T, Wolfle P. Multiple spin echoes in a normal Fermi liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984;53:2312. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowtell R, Bowley RM, Glover P. Multiple spin echoes in liquids in a high magnetic field. J. Magn. Reson. 1990;88:643–651. [Google Scholar]

- 4.He Q, Richter W, Vathyam S, Warren WS. Intermolecular multiple-quantum coherences and cross correlations in solution nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:6779–6800. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren WS, Richter W, Andreotti AH, Farmer BT. Generation of impossible cross-peaks between bulk water and biomolecules in solution NMR. Science. 1993;262:2005–2009. doi: 10.1126/science.8266096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren WS, Lee S, Richter W, Vathyam S. Correcting the classical dipolar demagnetizing field in solution NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995;247:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitt MH. Demagnetization field effects in two-dimensional solution NMR. Concepts Magn. Reson. 1996;8:77–103. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren WS, Ahn S, Mescher M, Garwood M, Ugurbil K, Richter W, Rizi RR, Hopkins J, Leigh JS. MR imaging contrast enhancement based on intermolecular zero quantum coherences. Science. 1998;281:247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong J, Chen Z, Kwok E. In vivo intermolecular double-quantum imaging on a clinical 1.5 T MR scanner. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000;43:335–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200003)43:3<335::aid-mrm3>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faber C, Zahneisen B, Tippmann F, Schroeder A, Fahrenholz F. Gradient-echo and CRAZED imaging for minute detection of Alzheimer plaques in an APPV717I × ADAM10-dn mouse model. Magn. Reson. Med. 2007;57:696–703. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter W, Richter M, Warren WS, Merkle H, Andersen P, Adriany G, Ugurbil K. Functional magnetic resonance imaging with intermolecular multiple-quantum coherences. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2000;18:489–494. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong J, Kwok E, Chen Z. fMRI of auditory stimulation with intermolecular double-quantum coherences (iDQCs) at 1.5T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001;45:356–364. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200103)45:3<356::aid-mrm1046>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu T, Kennedy S, Chen Z, Schneider K, Zhong J. Functional MRI at 3T using intermolecular double-quantum coherence (iDQC) with spin-echo (SE) acquisitions. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. 2007;20:255–264. doi: 10.1007/s10334-007-0093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JT, Faber C. BOLD imaging in the mouse brain using a turboCRAZED sequence at high magnetic fields. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;60:850–859. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin YY, Ahn S, Murali N, Brey W, Bowers CR, Warren WS. High-resolution, >1 GHz NMR in unstable magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:3732. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vathyam S, Lee S, Warren WS. Homogeneous NMR spectra in inhomogeneous fields. Science. 1996;272:92–96. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balla DZ, Melkus G, Faber C. Spatially localized intermolecular zero-quantum coherence spectroscopy for in vivo applications. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;56:745–753. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowtell R, Robyr P. Structural investigations with the dipolar demagnetizing field in solution NMR. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;76:4971–cit. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramanathan C, Bowtell RW. NMR imaging and structure measurements using the long-range dipolar field in liquids. Phys. Rev. E. 2002;66:041201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.66.041201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galiana G, Branca RT, Jenista ER, Warren WS. Accurate temperature imaging based on intermolecular coherences in magnetic resonance. Science. 2008;322:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1163242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branca RT, Galiana G, Warren WS. Signal enhancement in CRAZED experiments. J. Magn. Reson. 2007;187:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter W, Warren SW. Intermolecular multiple quantum coherences in liquids. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2000;12:396–409. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marques JP, Bowtell R. Optimizing the sequence parameters for double-quantum CRAZED imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;51:148–157. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]