Abstract

The CIRCE element, an inverted DNA repeat, is known to be involved in the temperature-dependent regulation of genes for heat shock proteins in a variety of organisms. The CIRCE element was identified as the target for the HrcA protein, which represses transcription of heat shock genes under normal growth temperature. Our data reveal that the CIRCE element is not involved in the temperature-dependent transcription of the groESL genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Apparently, R.capsulatus does not harbour an HrcA protein. The mechanisms of heat shock regulation of the groESL genes in R.capsulatus therefore diverge significantly from the regulatory pathway identified in other organisms. A structural analysis of the CIRCE RNA element revealed a stem of 11 nt pairs and a loop of only 5 nt. This folding differs from a structure with a 9 nt loop suggested previously on the basis of computer analysis. The RNA structure leads to a slight stabilization of the groESL mRNA that is more pronounced at normal growth temperature than under heat shock conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Microorganisms exhibit the capability to adapt to changes in their environment. A sudden upshift in temperature is known to induce the production of a specific set of proteins, the heat shock or heat stress proteins (HSPs). They are present in all organisms and lower the concentration of misfolded proteins by functioning as molecular chaperones or ATP-dependent proteases (reviewed in 1). In Escherichia coli, the induction of genes for cytoplasmic HSPs occurs primarily by a transient increase in the heat shock sigma factor σ32 (reviewed in 1). In the majority of bacteria, heat shock expression was found to be controlled through negative regulation mediated by a number of different repressor proteins (reviewed in 2).

The GroE chaperonin complex consisting of GroEL and GroES is involved in preventing cellular proteins from misfolding after temperature increase. The groEL-groES genes of Bacillus subtilis are transcribed by the vegetative sigma factor σA and are negatively controlled by the repressor HrcA (heat regulation at CIRCE) that is encoded by the first gene of the dnaK operon (reviewed in 2). The HrcA repressor exerts its activity through binding to CIRCE (controlling inverted repeat of chaperone expression), a highly conserved 9 bp inverted DNA repeat with a 9 bp spacer. The involvement of HrcA and CIRCE in heat shock regulation has been found or implicated in other Gram-positive bacteria as well, in α proteobacteria, cyanobacteria, Chlamydia and Spirochaeta (reviewed in 1). The important role of the CIRCE element was established, when mutations in one or both arms of this inverted repeat resulted in elevated transcription of downstream genes even at normal growth temperature (3,4). The activity of B.subtilis HrcA is modulated by the GroE chaperonin system. It was suggested that HrcA requires the GroE system for proper folding and is inactive upon temperature upshift, when GroES and GroEL become engaged in the refolding of denatured proteins (5). The CIRCE element is not only involved in transcriptional regulation of heat shock genes but also in post-transcriptional regulation. It was shown for B.subtilis that the CIRCE element could destabilize transcripts, if it is located in the immediate vicinity of a Shine–Dalgarno sequence (6).

Besides the CIRCE/HrcA-system, other negative mechanisms of regulation of heat-induced gene expression have been described in Gram-positive bacteria. One or two elements termed HAIR (HspR-associated inverted repeat) are located upstream of the Streptomyces clpB gene and the dnaK operon, respectively, and are bound by the repressor HspR (HSP regulator) at normal temperatures (reviewed in 7). The expression of the small HSP Hsp18 in Streptomyces albus is regulated by the repressor RheA. Most likely, this is mediated via binding of RheA to a palindromic recognition sequence located in the promoter region of the hsp18 gene as well as upstream of rheA (reviewed in 7). The class III heat shock genes of B.subtilis encoding several of the highly conserved Clp proteins are negatively regulated by the repressor CtsR (class three stress gene repressor) (reviewed in 1).

The groESL genes of the facultatively photosynthetic α proteobacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus are preceded by a typical CIRCE element. Previous investigations revealed that heat shock results in elevated levels of the corresponding gene products (8). However, nothing was known about transcriptional or post-transcriptional mechanisms of regulation of the groESL operon in R.capsulatus. We have currently addressed the role of the CIRCE element for transcriptional regulation and for transcript stability. Our data strongly suggest that the CIRCE element is not required for transcriptional regulation of the groESL operon, but that in R.capsulatus the mechanism of regulation differs from the established HrcA repressor mechanism. We could prove the configuration of a stable RNA secondary structure formed by the inverted repeat of CIRCE. This structure has a stabilizing effect on the groESL transcript.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides were cultivated aerobically and semi-aerobically, respectively, in minimal malate medium at 32°C (9). As indicated, the cultures were shifted to heat shock at 39°C. For cloning purposes E.coli strains were routinely grown in Standard I medium (Merck) at 37°C. If appropriate, antibiotics were added to the growth medium at the following concentrations: kanamycin 25 µg ml–1 (for E.coli and Rhodobacter), ampicillin 200 µg ml–1 (for E.coli) and tetracycline 20 µg ml–1 (for E.coli).

DNA manipulations

Cloning procedures were carried out using standard procedures (10). Restriction enzymes, the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from New England Biolabs. PCR primers were obtained from Carl Roth GmbH and PCR products were generated with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs).

Plasmid construction

All constructed plasmids were initially cloned in E.coli strain JM109 (11) and transferred into R.capsulatus wild type B10 (ATCC 33303) or R.sphaeroides wild type 2.4.1 (12) by diparental mating using E.coli strain S17-1 (13).

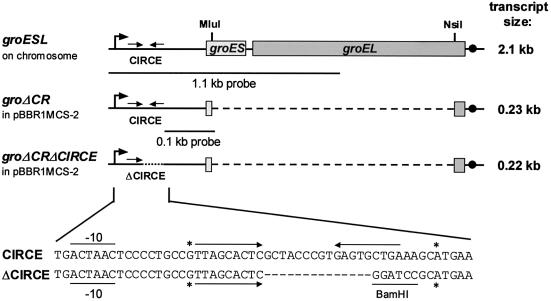

The plasmid pUSA71 carries the whole groESL operon of R.capsulatus B10 and was a kind gift from P. Hübner. It consists of a 2.3 kb EcoRI fragment of pUSA30 (groESL promoter region, groES, groEL 5′-end) and a 0.4 kb EcoRI–SphI fragment of pUSA48 (groEL 3′-end) cloned into the broad-host-range vector pPHU231 (8). For construction of the plasmid pBBRgroΔCR, pUSA71 was restricted with MluI/NsiI resulting in a 1.85 kb deletion of the groESL coding region (Fig. 1). The ends were filled in using Klenow fragment and religated. The groΔCR insert (positions 1–292, 2145–2302 of the groESL operon) (8) was amplified via PCR using the oligonucleotides PR-Cpn1+/EcoRI 5′-GGAATTCGTGGTCATGCGTTCCT CGG-3′ (restriction site underlined) and PR-Cpn2285-/HindIII 5′-CCCAAGCTTGCATGCAGCAATAACCGC-3′. After EcoRI/HindIII restriction, the PCR fragment was inserted into the EcoRI/HindIII-cut broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS-2 (14). For construction of plasmid pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE, the groΔCR insert was restricted with EcoRI/HindIII and cloned into EcoRI/HindIII-cut vector Bluescript SK+ (Stratagene). Afterwards the whole plasmid was amplified via PCR with exception of the last 18 of 27 nt of the CIRCE region using the oligonucleotides PR-Cpn180-/BamHI 5′-GGGGATCCGAGTGCTAACGGCAGGG-3′ and PR-Cpn217+/BamHI 5′-GGGGATCCGCATGAACCTGGA ACCTTAG-3′. After BamHI restriction the plasmid was religated, the groΔCRΔCIRCE insert was restricted with XbaI/HindIII and cloned into XbaI/HindIII-cut vector pBBR1MCS-2 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the bicistronic groESL operon of R.capsulatus and the deletions constructed in the groESL coding region and CIRCE. Due to better understanding the 5′-untranslated region is not to scale but enlarged 10-fold in comparison to the rest of the operon. Dashes indicate the bases or regions that were deleted. The two different DNA fragments used as probes for northern hybridization and the size of the detected transcripts are shown. The palindromic sequence of CIRCE is marked by arrows. The mRNA 5′-ends and the Rho-independent terminator of transcription are indicated by asterisks and dots, respectively. The expected –10-promoter region and the BamHI restriction site important in CIRCE deletion are underlined.

For in vitro degradation assays, groΔCR and groΔCRΔCIRCE (starting at the mRNA 5′-end, position 187–2302) were cloned under T7 control. For this purpose the plasmid pBBRgroΔCR and the oligonucleotides PR-Cpn187+/EcoRI 5′-GGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTA TAGTTAGCACTCGCTACCCG-3′ (T7 promoter in bold) and PR-Cpn2285-/HindIII and the plasmid pBBRgro ΔCRΔCIRCE and the oligonucleotides PR-Cpn187+ΔCIRCE/ EcoRI 5′-GGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGTTA GCACTCGGATCCGC-3′ and PR-Cpn2285-/HindIII, respectively, were used during PCR. After EcoRI/HindIII restriction, the PCR fragments were cloned into the EcoRI/HindIII-cut vector pUC18 (11).

For transfer of HrcA to R.capsulatus, the complete hrcA gene of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 was amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA and the oligonucleotides PR-hrcA291 +/PstI 5′-AACTGCAGGATGAACGACCGCTCGCGCG-3′ (start codon in bold) and PR-hrcA1314-/XbaI 5′-GCTC TAGAGTCATCCCTTGCCGCGGTCG-3′ (stop codon in bold). After PstI/XbaI restriction, the PCR fragment was cloned into PstI/XbaI-cut vector pRK415 (15) resulting in plasmid pRKhrcA.

RNA isolation and quantification of mRNA by northern blot analysis

Bacteria from 20 ml of an aerobic culture of Rhodobacter were harvested and total RNA was isolated as described (16). To determine mRNA half-lives, during exponential growth phase at an OD660 of 0.4–0.6 rifampicin was added to the cultures (300 µg ml–1), and cells were collected at the indicated time points. Northern hybridization was performed as described (17). Total RNA (10 µg per lane) was electrophoresed on 1% (w/v) agarose 2.2 M formaldehyde gels and transferred to Biodyne B membrane (Pall) using a vacuum blot apparatus (Appligene). groES- and groESL-specific DNA fragments of R.capsulatus were radiolabelled with [α-32P]dCTP using nick translation (nick translation kit, USB). The oligonucleotide used for hybridization with fragmented Rhodobacter 23S rRNA was 5′-CTTAGATGTTTCAGTTCCC-3′ corresponding to the 23S rDNA positions 187 to 205 (E.coli numbering). Oligonucleotide (10 pmol) was labelled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). The DNA fragments and the oligonucleotide used for hybridization were purified using micro columns (Probe Quant G-50, Amersham Biosciences). Per hybridization reaction 0.5–2 × 106 c.p.m. were used. The radiolabelled bands were visualized and quantified using a phosphorimaging system (Personal Molecular Imager FX, Bio-Rad) and the appropriate software (Quantity One, Bio-Rad).

Preparation of genomic DNA and Southern blot analysis

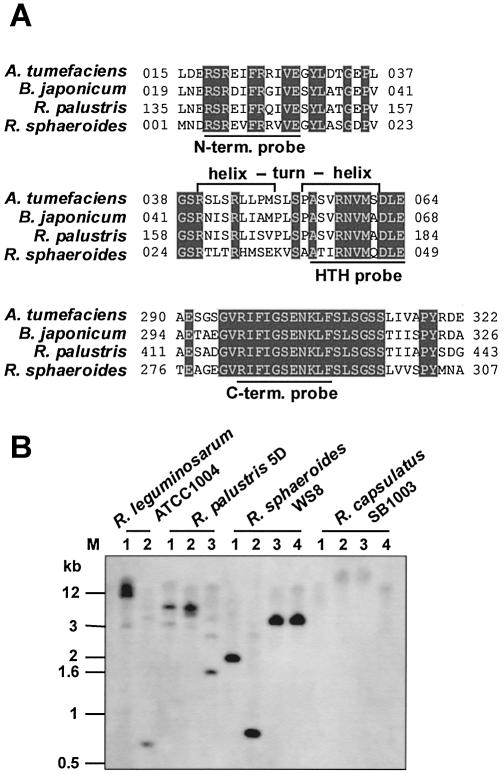

Preparation of genomic DNA was done as described (18). Ten micrograms of genomic DNA from Rhizobium leguminosarum strain ATCC 1004, Rhodopseudomonas palustris strain 5D, R.sphaeroides strain WS8 (19) and R.capsulatus strain SB1003 (20) were digested overnight with various restriction enzymes. The DNA was separated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and transferred to Biodyne B membrane (Pall) using a vacuum blot apparatus (Appligene). As DNA molecular weight marker, 1 kb DNA ladder (Gibco) was used. Hybridization was performed following the standard protocol as described (21). The 33 nt oligonucleotides used for hybridization with the hrcA gene were 5′-TCGCGCGAGGTCTTCCGCCGCG TGGTGGAAGGC-3′ (N-term. probe) corresponding to 11 amino acids in the N-terminal region, 5′-GCGACCA TCCGCAACGTGATGCAGGACCTGGAG-3′ (HTH probe) corresponding to 11 amino acids in the predicted helix–turn–helix motif (22) and 5′-CGCATCTTCATCGGCTCG GAGAACAAGCTGTTC-3′ (C-term. probe) corresponding to 11 amino acids in the C-terminal half of HrcA (see Fig. 6A). The conversion of the amino acid sequence of R.sphaeroides HrcA to nucleotides was done with respect to the codon preference of R.capsulatus using the backtranslation program (http://entelechon.com/eng/backtranslation.html). Per hybridization reaction 2 × 106 c.p.m. of the 32P-labelled oligonucleotide were used. The radiolabelled bands were visualized as described above.

Figure 6.

HrcA in different α proteobacteria. (A) Alignment of part of the N- and C-terminal region of four HrcA-homologous proteins from members of the α subgroup of proteobacteria. Conserved amino acids are shaded and the predicted helix–turn–helix motif is indicated. The 11 amino acid sequences corresponding to the oligonucleotides used for the identification of the hrcA gene of R.capsulatus are underlined. (B) Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNA of four α proteobacteria was digested with the restriction enzymes BamHI (1), XhoI (2), SacI (3) and SalI (4). Afterwards the DNA was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nylon membrane and hybridized with the 33 nt oligonucleotide ‘C-term. probe’ corresponding to 11 amino acids in the C-terminal half of HrcA in α proteobacteria with respect to the codon preference of R.capsulatus. M, DNA molecular weight marker, approximate sizes are indicated.

Analysis of RNA secondary structure

Determination of RNA secondary structure was performed as described (reviewed in 23). In vivo methylation of RNA with DMS was done by adding 1% (v/v) DMS to a rapidly growing aerobic R.capsulatus culture for 5 min at 32°C. DMS, which can permeate through membranes, methylates unpaired adenosine residues at N1 and unpaired cytidines residues at N3. Modified residues can be identified by reverse transcription as the modification blocks the primer extension reaction at the nucleotide preceding the modified residue. Harvesting of cells and RNA isolation were performed as described above. Mapping of modified nucleotides was accomplished by primer extension analysis as described (17) using 10 µg of total RNA and the 32P-labelled oligonucleotide PR-Cpn244- 5′-GCGGTTTGAATGCCATCTGGG-3′ hybridizing to the groESL transcript ∼60–80 nt downstream of the major 5′-end. The primer extension products were analysed on a sequencing gel side by side to the products of the sequencing reactions using the same labelled primer. DNA sequences were obtained by dideoxy sequencing (24) using [α-35S]dATP and the T7 Sequencing Kit (Pharmacia).

In vitro degradation assays

The 265 nt groΔCR and the 251 nt groΔCRΔCIRCE RNAs were transcribed in vitro from the HindIII linearized pUC18 plasmids in the presence of [α-32P]UTP using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) (25). For 5′-end labelling, the groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA was transcribed in vitro from the HindIII linearized pUC18 plasmid in the absence of [α-32P]UTP, dephosphorylated using alkaline phosphatase (USB) and labelled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). RNase E and the degradosome were purified from R.capsulatus strain 37b4 (DSMZ 938) and in vitro degradation assays were performed as described (26). Approximately 4000 c.p.m. of labelled RNA were incubated with 0.4 µl of degradosome fractions (∼0.7 ng µl–1 RNase E) at 32 and 39°C, respectively. The reaction was carried out in buffer optimized for RNase E (27) supplemented with 5 mM ATP to enhance helicase and phosphorolytic exoribonuclease activity of the degradosome. After separation on 7 M urea, 6% PAA gels the generated radiolabelled RNA fragments were quantified as described above. As RNA molecular weight marker, RNA century marker (Ambion) was transcribed in vitro in the presence of [α-32P]UTP according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

RESULTS

Structural analysis of the CIRCE region of the groESL transcript from R.capsulatus

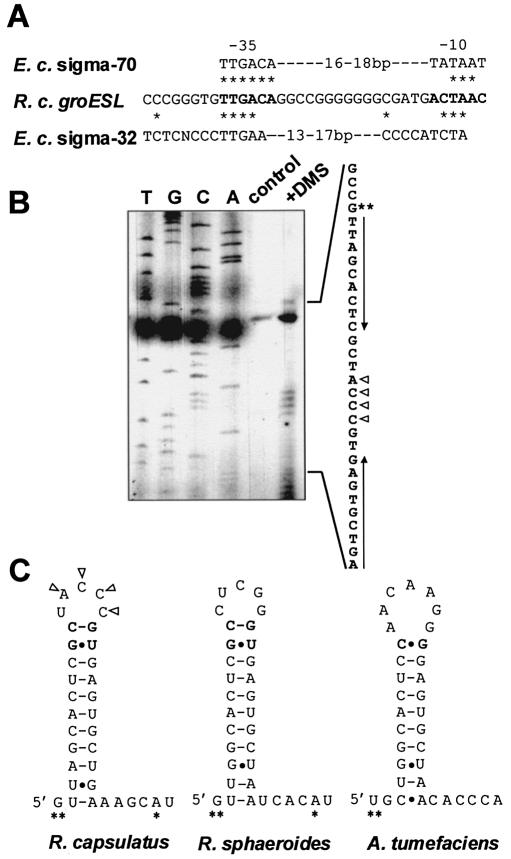

The groESL transcript from R.capsulatus has previously been characterized (8) (Fig. 1). In this study, the major mRNA 5′-end was localized 10 nt downstream of the –10 region of a putative promoter and immediately upstream of the CIRCE region. Comparison of the putative promoter region and the consensus sequences of the E.coli sigma-70 promoter and the sigma-32 promoter revealed that the promoter region exhibits homology to both consensus sequences (Fig. 2A). Although the important function of the CIRCE region for heat shock regulation has been shown for quite a number of bacterial species, the RNA secondary structure of none of the CIRCE elements has been confirmed experimentally. The sequence of the R.capsulatus groESL CIRCE region differs from the CIRCE consensus sequence (reviewed in 28) by only one mismatch out of 18 nt. Chemical modification of the RNA in vivo with DMS followed by primer extension analysis (Fig. 2B) revealed that the loop of the R.capsulatus groESL CIRCE RNA secondary structure consists of 5 nt with four residues modified by DMS (Fig. 2C). The structure is also in agreement with the most stable structure predicted by computer analysis using the mfold program version 2.3 (http://bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold/old/rna) (29,30). For this structure, the program calculates a thermodynamic stability of ΔG –17.6 kcal mol–1 at 32°C and –15.8 kcal mol–1 at 39°C. The structure of CIRCE in front of the groESL operon of R.sphaeroides and Agrobacterium tumefaciens predicted by computer analysis also contains a small loop consisting of only 5 and 7 nt, respectively (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Predicted promoter region of the R.capsulatus groESL operon and RNA secondary structure of CIRCE. (A) Homology of the putative groESL promoter sequence of R.capsulatus (R. c. groESL) to the consensus sequences of the E.coli vegetative sigma factor promoter (E. c. sigma-70) and the E.coli heat shock sigma factor promoter (E. c. sigma-32) (42). Identical residues are marked by asterisks. (B) Primer extension analysis after in vivo methylation was performed by adding DMS to a rapidly growing culture before RNA isolation. Methylated nucleotides were mapped by primer extension analysis (lane: +DMS) using the oligonucleotide PR-Cpn244- hybridizing to the groESL transcript ∼60–80 nt downstream of the major 5′-end. The modification blocks the primer extension reaction at the nucleotide preceding the modified residue. The control lane shows the extension products of unmodified RNA. Sequencing reactions obtained with the same oligonucleotide were run on a sequencing gel side by side with the products of the primer extension reaction and are labelled with T, G, C and A. Triangles indicate modified nucleotides. The major 5′-end is indicated by two asterisks and the palindromic CIRCE sequence is marked by arrows. (C) RNA secondary structure of the CIRCE region in the groESL 5′-untranslated region of three α proteobacteria. Modified nucleotides detected by in vivo methylation are indicated by triangles. Nucleotides of the variable region of CIRCE forming additional base pairs of the stem are in bold. 5′-ends are marked by asterisks, Watson–Crick base pairs are indicated by dashes and non-Watson–Crick base pairs by dots.

Effect of temperature on the groESL transcript level and stability

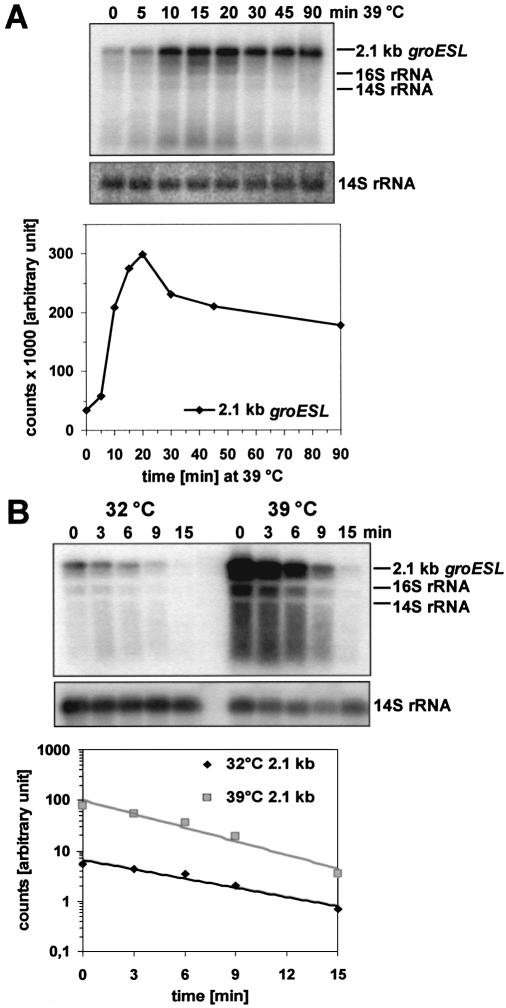

In order to quantify the effect of heat shock on the groESL expression directly, we performed northern blot analyses of total RNA from R.capsulatus wild type B10. A DNA region of dyad symmetry spanning from 25 to 44 nt downstream of the stop codon of groESL and followed by 5 U residues was proposed to function as transcriptional terminator of the groESL transcript (8) (Fig. 1). We performed RNase protection analyses and could indeed localize the major 3′-end of the groESL transcript within this U stretch (not shown). Using the groESL-specific 1.1 kb DNA probe, we detected a transcript with a size of 2.1–2.2 kb, which is in agreement with the predicted length of the bicistronic groESL transcript based on the experimentally determined 5′- and 3′-ends. A temperature increase from 32 to 39°C resulted in a transient 8–10-fold increase of the groESL transcript level, which was maximal 20 min after the transition (Fig. 3A, Table 1). After a cold shock from 32 to 20°C no groESL mRNA was detectable on northern blots, suggesting a strong repression of transcription under these conditions (not shown). In order to test the effect of heat shock on the stability of the groESL transcript, we added rifampicin to cultures grown at 32°C or 20 min after the transition to 39°C. While the average half-life of the 2.1 kb groESL transcript was 4.2 ± 0.3 min at 32°C, it decreased 1.4-fold to 3.1 ± 0.4 min at 39°C (Fig. 3B, Table 1). Thus, the elevated groESL transcript levels after heat shock are not due to increased mRNA stability. In addition, the stability of non-heat-induced transcripts was determined. A 1.6- and 2-fold decrease of stability after shift from 32 to 39°C was observed for the oxygen-regulated 0.5 kb pufBA and 2.7 kb pufBALMX mRNA encoding pigment binding proteins of the photosynthetic apparatus in R.capsulatus (not shown). The 0.4 kb cspA transcript coding for cold shock protein A in R.capsulatus did also show a reduced stability by a factor of 2.8. These data indicate that the destabilization of the groESL mRNA upon temperature increase rather represents a general effect of temperature on mRNA stability than a specific effect on groESL half-life.

Figure 3.

Northern blot analyses of total RNA from R.capsulatus wild type B10. (A) Induction of the 2.1 kb groESL transcript following heat shock at 39°C. RNA was isolated from R.capsulatus B10 grown at 32°C (0 min) and at the indicated times after a temperature shift to 39°C, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nylon membrane and probed with the groESL-specific 1.1 kb probe. At the bottom, the same blot was rehybridized with a probe specific for fragmented 23S rRNA (14S rRNA) of Rhodobacter. The mRNA bands were quantified by phosphorimaging and normalized with respect to the rRNA amount. Values were plotted as a function of time. (B) Stability of the 2.1 kb groESL RNA at 32 and 39°C. Rhodobacter capsulatus B10 cells were cultivated over night at 32°C before shifting one culture to heat shock at 39°C. After 20 min at 39 and 32°C, respectively, the antibiotic rifampicin was added to the cultures (0 min). RNA was isolated from samples taken at various time points and groESL-specific transcripts were monitored by northern hybridization using the 1.1 kb probe. Half-lives were determined by quantification of the mRNA bands by phosphorimaging. The mRNA amount was normalized with respect to the rRNA amount and the values were plotted on a semi- logarithmic scale as a function of time. The groESL RNA half-life was calculated to 4.5 min at 32°C and 3.4 min at 39°C, respectively.

Table 1. Effect of gro deletions on the expression and the stability of the resulting transcripts after thermal upshock of R.capsulatus from 32 to 39°C.

| mRNA | Induction factora | Half-life (min) at 32°Cb | Half-life (min) at 39°Cb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 kb groESL | 8–10 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.4 |

| 0.23 kb groΔCR | 3–5 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| 0.22 kb groΔCRΔCIRCE | 3–6 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

aThe induction factor is the ratio of the mRNA amount at 32°C and the maximum amount at 39°C and was determined by at least three different experiments.

bHalf-lives were determined by analysis of at least three different northern blots while the maximum deviation is indicated (±).

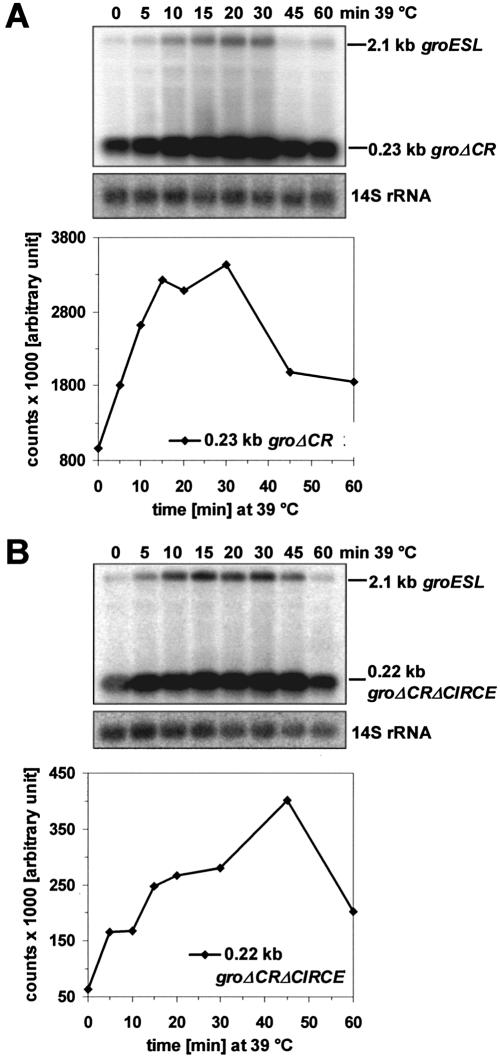

Effect of a deletion spanning most of the coding region on gro transcript levels and stability

In order to test whether the coding region of the groESL operon harbours any elements that significantly affect transcript levels or stability, we constructed plasmid pBBRgroΔCR, which has most of the groESL coding region deleted (Fig. 1). Plasmid pBBRgroΔCR was transferred to the R.capsulatus wild type B10 and expressed in trans while the wild type groESL copy is expressed from the chromosome. Inactivation of groEL by insertion of a resistance cassette failed (8) indicating that the groESL genes are essential for R.capsulatus. Southern blot analysis revealed that the pBBR1-derived plasmid is present in approximately seven copies in R.capsulatus (not shown). When cultures were shifted from 32 to 39°C and northern blot analysis was performed using the groES-specific 0.1 kb DNA probe, the levels of the 2.1 kb groESL and the 0.23 kb groΔCR transcript increased with almost the same kinetics. While the level of the groESL mRNA increased by a factor of 8 to 10, the groΔCR mRNA transcribed from plasmid pBBRgroΔCR was induced only 3–5-fold (Fig. 4A, Table 1). In the presence of the groΔCR mRNA the groESL transcript level decreased already after 45 min at 39°C. A higher level of the short groΔCR transcript before heat shock induction might be due to the increased copy number of the plasmid and this could account for the lower increase after heat shock induction. We also determined the half-life of the 0.23 kb groΔCR transcript during growth at 32°C and 20 min after a shift to 39°C (Table 1). It was nearly identical at 32°C (4.2 ± 0.5 min versus 4.2 ± 0.3 min for the groESL transcript) and 20 min after a shift to 39°C (3.0 ± 0.5 min versus 3.1 ± 0.4 min) when compared to the half-life of the full-length groESL transcript. Our data suggest that the coding region harbours no sequences that are involved in rate-limiting mRNA decay.

Figure 4.

Northern blot analyses of total RNA from R.capsulatus B10 cells containing plasmid pBBRgroΔCR or pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE. (A) Induction of 0.23 kb groΔCR and (B) 0.22 kb groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript following heat shock at 39°C. RNA was isolated from R.capsulatus B10 containing plasmid pBBRgroΔCR or plasmid pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE grown at 32°C (0 min) and at the indicated times after a temperature shift to 39°C. gro- specific transcripts were monitored by northern hybridization using the groES-specific 0.1 kb probe. The mRNA amount was determined as described and plotted as a function of time.

Effect of a deletion of the CIRCE element on gro transcript levels

The main goal of our work was to study the role of the CIRCE element in heat shock-dependent gene expression. Towards this end, we deleted the CIRCE element from plasmid pBBRgroΔCR (Fig. 1). After transferring the resulting plasmid pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE into the R.capsulatus wild type B10, we followed the expression of the chromosomal copy of groESL and of the plasmid encoded copy of groΔCRΔCIRCE. When the culture was shifted from growth at 32 to 39 °C and northern blot analysis was performed using the 0.1 kb probe, the level of both transcripts increased. While the level of the wild type transcript increased by a factor of about 8 to 10, the level of the 0.22 kb groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript increased by a factor of 3 to 6, which was in the same range as observed for the increase of the groΔCR mRNA level after heat shock (Fig. 4B, Table 1). In addition, in some northern experiments the maximum induction of the groΔCRΔCIRCE mRNA appeared to be delayed during the time course. In the presence of the groΔCRΔCIRCE mRNA the groESL transcript level decreased significantly after 60 min at 39°C, as it was previously observed in the presence of the groΔCR transcript.

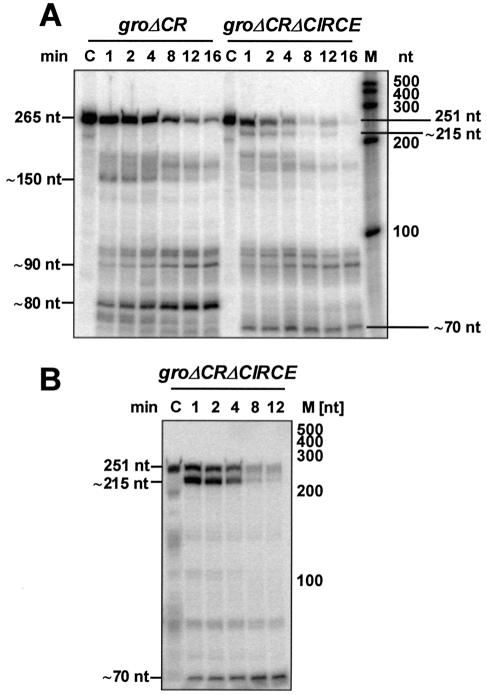

Effect of the CIRCE element on gro transcript stability in vivo and in vitro

We also determined the half-life of the 0.22 kb groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript during growth at 32°C and 20 min after a shift to 39°C (Table 1). It was even shorter than the half-life of the 0.23 kb groΔCR mRNA at 32°C (2.6 ± 0.2 min versus 4.2 ± 0.5 min) and after heat shock (2.3 ± 0.1 min versus 3.0 ± 0.5 min). Thus, the mRNA structure of the CIRCE element stabilizes the groESL transcript in vivo by a factor of about 1.3 to 1.6. To confirm a stabilizing effect of CIRCE, groΔCR and groΔCRΔCIRCE were cloned under T7 control and transcribed in vitro. Both transcripts were tested in an in vitro degradation assay using purified degradosome of R.capsulatus. An mRNA degrading, high molecular weight complex, termed the degradosome, was initially identified and characterized in E.coli (31). We purified an analogous complex from R.capsulatus, which comprises endoribonuclease E, the key enzyme for mRNA degradation, two ATP-dependent RNA helicases, the transcription termination factor Rho and the 3′→5′ exoribonuclease PNPase being a minor component of the complex (24). The half-life of the 251 nt groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA monitored in the in vitro degradation assay was 2-fold decreased compared to the stability of the 265 nt groΔCR RNA at 32°C (1.6 versus 3.2 min, Fig. 5A). At the elevated temperature of 39°C, a 1.4-fold reduced groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA stability could be observed (0.9 versus 1.3 min, not shown). These results are in agreement with the calculated in vivo half-lives. In addition, the nature of a 215 nt degradation product of the groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA, which did not appear during degradation of the groΔCR transcript, should be investigated (Fig. 5A). For this purpose, degradation of 5′-labelled groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA was monitored (Fig. 5B). This experiment revealed that the groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA is initially cleaved in the U-rich region of the Rho independent terminator of transcription resulting in a 215 nt 5′-labelled fragment. One of the subsequent processing events occurs 70 nt downstream of the mRNA 5′-end.

Figure 5.

In vitro degradation of the groΔCR and the groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript. (A) [α-32P]UTP internally labelled groΔCR and groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA, respectively, was incubated with RNase E containing fraction at 32°C for the time indicated. Fragments were separated on denaturing PAA-gels. C, RNA in the absence of added protein for 16 min at 32°C. Approximate sizes of the major degradation products are given. M, RNA molecular weight marker. The in vitro half-life of the groΔCR and the groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript at 32°C was calculated to 3.2 and 1.6 min, respectively. (B) [γ-32P]ATP 5′-labelled groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA was incubated with RNase E containing fraction at 32°C for the time indicated. Fragments were separated on a denaturing PAA-gel. C, RNA in the absence of added protein for 12 min at 32°C. Approximate sizes of the two 5′- labelled degradation products are given. M, RNA molecular weight marker.

The R.capsulatus genome apparently does not encode the HrcA regulator protein

We could not find a sequence with strong homology to HrcA in R.capsulatus using the almost completed R.capsulatus genome project through the ERGO home page (http://igweb.integratedgenomics.com), even when we used the HrcA sequence of the closely related Rhodobacter sphaeroides for homology search. In addition, an hrcA homologous sequence could not be identified upstream of the dnaK operon, a region where the hrcA gene is located in many bacterial species. To test for the presence of an hrcA gene, we used three 33 nt DNA oligonucleotides with respect to the codon preference of R.capsulatus as probes in Southern blot analysis. The oligonucleotide ‘C-term. probe’ corresponds to 11 amino acids in the C-terminal half of HrcA where the amino acid sequence is 100% identical among the known HrcA proteins found in α proteobacteria (Fig. 6A). No specific cross-reaction of the chromosomal DNA from R.capsulatus to the hrcA probe could be detected by low-stringency hybridization (Fig. 6B). On the same Southern blot we were not only able to detect the hrcA-specific sequences from R.sphaeroides but also from R.palustris and R.leguminosarum, both more distantly related to R.capsulatus than R.sphaeroides. Southern blot analysis using the oligonucleotide ‘N-term. probe’ corresponding to the N-terminus of HrcA (Fig. 6A) showed no cross-hybridization as well (not shown). A region of significant homology between different bacterial HrcA proteins was identified as a helix–turn–helix DNA binding motif in Bacillus thermoglucosidasius (22). The oligonucleotide ‘HTH probe’ corresponds to part of the homologous region from R.sphaeroides HrcA with respect to the codon preference of R.capsulatus (Fig. 6A). This oligonucleotide hybridized to chromosomal DNA of R.capsulatus, but also showed cross-reaction to R.sphaeroides DNA fragments not specific for the hrcA gene (not shown). In addition, we amplified the whole hrcA gene of R.sphaeroides WS8 resulting in a 1.1 kb DNA probe, but no cross-hybridization to R.capsulatus DNA of two different wild types could be detected (not shown). These results strongly suggest that the R.capsulatus genome does not encode the HrcA regulatory protein.

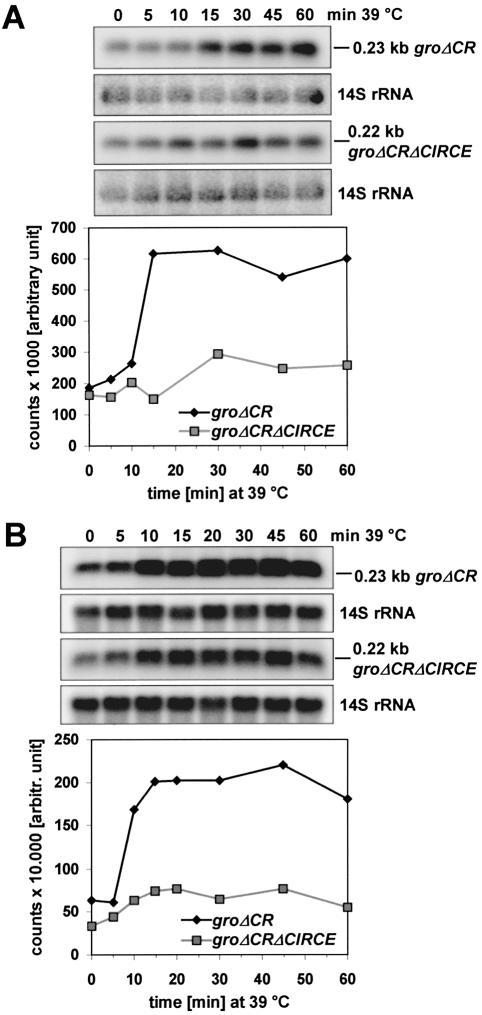

Transcripts groΔCR and groΔCRΔCIRCE in an HrcA-positive background

Plasmid pBBRΔCR and pBBRΔCRΔCIRCE were transferred to R.sphaeroides, the closest relative of R.capsulatus that contains an HrcA-homologous protein. The groESL CIRCE element from both bacterial species shows high conservation of sequence as well as localization of the inverted repeat, which should guarantee binding of HrcA from R.sphaeroides to the CIRCE inverted repeat of R.capsulatus (32). Rhodobacter sphaeroides wild type 2.4.1 cultures containing plasmid pBBRΔCR and pBBRΔCRΔCIRCE, respectively, were shifted from 32 to 39°C and northern blot analysis was performed using the R.capsulatus-specific 0.1 kb probe (Fig. 7A). The level of the groΔCR mRNA increased by a factor of 3 to 5, which was in the same range as observed in R.capsulatus. In contrast, the groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript showed a reduced induction after heat shock by a factor of only 1.5 to 2, indicating a different regulation of groΔCRΔCIRCE expression in R.sphaeroides. After transfer of plasmid pRKhrcA harbouring the complete R.sphaeroides hrcA gene to R.capsulatus containing plasmid pBBRgroΔCR and pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE, respectively, and shift from 32 to 39°C, a reduced induction of 1.3–2.8-fold of the groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript and a 3–5-fold induction of the groΔCR mRNA was also detectable by northern blot analysis (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Induction of the 0.23 kb groΔCR and the 0.22 kb groΔCRΔCIRCE transcript in the HrcA-background following heat shock at 39°C. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA from R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 cells containing plasmid pBBRgroΔCR or pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE. RNA was isolated from R.sphaeroides strains grown at 32°C (0 min) and at the indicated times after a temperature shift to 39°C. Rhodobacter capsulatus gro-specific transcripts were monitored by hybridization on the same northern membrane using the 0.1 kb probe. The mRNA amount was determined as described and plotted as a function of time. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA from R.capsulatus B10 cells containing plasmids pRKhrcA and pBBRgroΔCR or pRKhrcA and pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE. RNA was isolated from R.capsulatus strains grown at 32°C (0 min) and at the indicated times after a temperature shift to 39°C. Rhodobacter capsulatus gro- and rRNA-specific transcripts were monitored and quantified as described.

DISCUSSION

The CIRCE element has been identified as a DNA element involved in heat shock regulation of the groESL operon and is considered as a repressor-binding site (3). Furthermore, a role in regulation at post-transcriptional level could be assigned to CIRCE (6). Despite the importance of the CIRCE element, all predictions on its RNA structures were solely based on RNA folding algorithms. We present the first experimental analysis for a CIRCE mRNA structure. The CIRCE DNA sequence from R.capsulatus matches the established CIRCE consensus sequence almost perfectly (reviewed in 28). Our results support a folding of the CIRCE RNA structure from R.capsulatus with extended base pairings between the two arms of the stem and a reduced loop comprising only five bases. In contrast, the model suggested previously in R.sphaeroides consists of a 9 nt stem formed by the inverted repeat sequence and a loop consisting of the 9 nt variable region (32). The sequences of CIRCE from R.sphaeroides and A.tumefaciens also allow the folding of a loop consisting of only 5 and 7 nt, respectively. It is likely that CIRCE elements from other species could also adopt the RNA structure we revealed for R.capsulatus.

A role of RNA processing in heat shock-dependent gene expression has been reported before (33,34). However, in R.capsulatus wild type the stability of the groESL transcript decreased by a factor of 1.4 during heat shock. Thus, differential mRNA stability does not contribute to heat shock-dependent increase of groESL mRNA levels. Since the groESL transcript level was increased by a factor of 8 to 10 after heat shock while the stability dropped by a factor of 1.4, the activation of the groESL promoter is indeed more than 8–10-fold. Decreasing stability at higher temperature was also observed for the two puf transcripts and the cspA mRNA of R.capsulatus demonstrating that this effect is not restricted to groESL. Nevertheless, our data indicate that the temperature-dependent stability of the CIRCE mRNA structure (ΔG = –17.6 kcal mol–1 at 32°C and –15.8 kcal mol–1 at 39°C) contributes to the reduced groESL mRNA stability at 39°C: transcript groΔCRΔCIRCE which lacks the CIRCE structure at the 5′-end shows almost the same stability at 32 and at 39°C.

Our data revealed that the CIRCE element exerts a slight stabilizing effect on the groESL mRNA both in vivo and in vitro. Deletion of the CIRCE element results in a decrease of the gro mRNA half-life by a factor of 1.3 to 1.6 in vivo. This finding is opposite to data obtained for CIRCE in the B.subtilis dnaK operon. The CIRCE element destabilized the mRNA if located in the immediate vicinity of a Shine–Dalgarno sequence (6). In contrast, the CIRCE region of R.capsulatus is not located in the immediate vicinity of 2 nt, but 23–26 nt upstream of the putative ribosomal binding site. The involvement of an RNA secondary structure in post-transcriptional regulation of heat shock gene expression has been proposed for several rhizobial species (35). The secondary structure of the negatively cis-acting element ROSE (repression of heat shock gene expression) seems to be temperature-dependent and controls ribosome access to the Shine–Dalgarno sequence. In contrast to melting of the 3′-end of the ROSE mRNA at higher temperatures, the palindromic CIRCE sequence forms a stem–loop structure, which is extremely stable at any temperature.

In vitro, deletion of the CIRCE element resulted in decrease of the gro mRNA stability by a factor of 1.4 to 2.0, which is in accordance with the data observed by northern blot analysis. Our data indicate that RNase E and the degradosome mediate the turnover of the groESL mRNA in the cell. The CIRCE stem–loop, which is located immediately downstream of the major 5′-end might be involved in prevention of RNase E binding. Endoribonuclease E is known to attach to the RNA 5′-end before cleaving at the proximal accessible site (36). Binding is inhibited by both stem–loop structures and triphosphates at the 5′-end (37,38). Deletion of the CIRCE element would cause faster interaction of RNase E with the groESL mRNA 5′-end resulting in enhanced degradation and reduced stability. Nevertheless, our data reveal that the presence of the CIRCE RNA structure at the 5′-end is not required for the stability of the groESL mRNA to the same extent as reported for other mRNAs. Deletion of secondary structures at the 5′-end of the ompA mRNA of E.coli (37), the ermC mRNA of B.subtilis (39) or the pufBA mRNA from R.capsulatus (17) results in extremely rapid degradation of the corresponding mRNA.

Our results provide first hints at the degradation mechanism of the groESL transcript by the action of RNase E and the degradosome. Deletion of CIRCE results in rapid recognition of one RNase E cleavage site in the U-rich region of the Rho-independent terminator of transcription. In contrast, this site is not primarily cleaved, when CIRCE is present at the RNA 5′-end. Several examples have been reported in which the rate-limiting step for mRNA decay is an endonucleolytic cleavage that takes place at the 3′-end. The 3′→5′ degradation of the rpsO mRNA encoding the ribosomal protein S15 of E.coli is initiated by RNase E cleavage upstream of the transcriptional terminator followed by rapid exonucleolytic degradation by PNPase (40). The catalytic domain of RNase E was also shown to have an inherent mode of cleavage in the 3′→5′ direction (41). Subsequent processing of the groΔCRΔCIRCE RNA takes place downstream of the major 5′-end resulting in an ∼70 nt fragment, which presumably corresponds to one of the major groΔCR cleavage products with a size of ∼80 nt. Cleavage in this region would remove the slightly stabilizing CIRCE stem–loop and deliver the generated 3′-end to additional components of the degradosome.

Surprisingly, our data obtained for the temperature- dependent expression of the groESL sequence lacking the CIRCE element are not in accordance with the established model of heat shock regulation by CIRCE and HrcA. Deletion of the CIRCE element did not alter the relative increase of gro mRNA after heat shock when compared to the control strain. This strongly suggests that the CIRCE element is not involved in the heat shock regulation of the groESL operon of R.capsulatus. These assumptions are supported by the finding that R.capsulatus unexpectedly does not appear to harbour a gene for the HrcA protein, which is believed to repress groESL transcription at normal temperature by binding to the CIRCE element. HrcA-homologous proteins have been identified in over 100 both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria and our experiments confirmed their presence in three α proteobacteria including the closely related bacterium R.sphaeroides. Nevertheless, the reason for the apparent deficiency of HrcA in R.capsulatus remains elusive even now. In contrast to R.capsulatus, the transcripts groΔCR and groΔCRΔCIRCE behave differently in the background of R.sphaeroides harbouring an HrcA-homologous protein. Deletion of the CIRCE element clearly reduced the induction of the transcript after heat shock in R.sphaeroides (1.5–2-fold versus 3–6-fold in R.capsulatus). Similar results were obtained after transfer of the plasmid-encoded hrcA gene to R.capsulatus containing plasmid pBBRgroΔCRΔCIRCE (1.5–2.8-fold with pRKhrcA versus 3–6-fold without). In A.tumefaciens, the almost complete deletion of CIRCE resulted in transcript levels not equivalent to the levels of the mRNA containing the CIRCE element (34), which indicates that the total values of the two transcripts are not comparable. In consequence, binding of the HrcA-homologous protein of R.sphaeroides to the CIRCE element of R.capsulatus seems to repress groΔCR transcription at 32°C. The absence of HrcA binding to the groΔCRΔCIRCE construct at 32°C contributes to its reduced induction after heat shock.

Interestingly, the dnaKJ operon of R.capsulatus does not contain a CIRCE element. This finding is in agreement with the absence of the repressor HrcA in R.capsulatus, which is also known to be involved in dnaK regulation at CIRCE (6). At present, the only function we can assign to the CIRCE element in the groESL operon of R.capsulatus is stabilization of the groESL mRNA, which contributes to higher expression levels at both 32 and 39°C. This stabilizing effect is more pronounced at 32°C than at 39°C, thus not being involved in heat-dependent regulation of the expression. Comparison of the putative groESL promoter region of R.capsulatus to the E.coli σ70 and σ32 consensus sequence indicates a σ32-dependent regulation of heat shock expression or a dual regulation mediated by both sigma factors, as it has also been considered for the regulation of the groESL1 operon of R.sphaeroides (32). An alternative sigma factor with strong similarity to RpoH proteins from other bacterial species does exist in the R.capsulatus genome. Further investigations should elucidate the reasons for loss of HrcA in R.capsulatus and reveal the complete regulation of the groESL heat shock response in this bacterium possibly including a third, unknown component.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank G. Homuth for helpful comments on the manuscript and P. Hübner for providing plasmids containing the groESL operon of R.capsulatus. This work was supported by the DFG graduate programme ‘Biochemie von Nukleoproteinkomplexen’ and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yura T., Kanemori,M. and Morita,M.T. (2000) The heat shock response: regulation and function. Bacterial Stress Responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narberhaus F. (1999) Negative regulation of bacterial heat shock genes. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuber U. and Schumann,W. (1994) CIRCE, a novel heat shock element involved in regulation of heat shock operon dnaK of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol., 176, 1359–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Asseldonk M., Simons,A., Visser,H., de Vos,W.M. and Simons,G. (1993) Cloning, nucleotide sequence and regulatory analysis of the Lactococcus lactis dnaJ gene. J. Bacteriol., 175, 1637–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogk A., Homuth,G., Scholz,C., Kim,L., Schmid,F.X. and Schumann,W. (1997) The GroE chaperonin machine is a major modulator of the CIRCE heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J., 16, 4579–4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homuth G., Mogk,A. and Schumann,W. (1999) Post-transcriptional regulation of the Bacillus subtilis dnaK operon. Mol. Microbiol., 32, 1183–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Servant P. and Mazodier,P. (2001) Negative regulation of the heat shock response in Streptomyces. Arch. Microbiol., 176, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hübner P., Dame,G., Sandmeier,U., Vandekerckhove,J., Beyer,P. and Tadros,M.H. (1996) Molecular analysis of the Rhodobacter capsulatus chaperonin (groESL) operon: purification and characterization of Cpn60. Arch. Microbiol., 166, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drews G. (1983) Mikrobiologisches Praktikum. Springer Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbour, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanisch-Perron C., Viera,J. and Messing,J. (1985) Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene, 33, 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sistrom W.R. (1960) A requirement for sodium in the growth of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Gen. Microbiol., 22, 778–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon R., Priefer,U. and Pühler,A. (1983) A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology, 1, 784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovach M.E., Elzer,P.H., Hill,D.S., Robertson,G.T., Farris,M.A., Roop,R.M.,II and Peterson,K.M. (1995) Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene, 166, 175–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keen N.T., Tamaki,S., Kobayashi,D. and Trollinger,D. (1988) Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene, 70, 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieuwlandt D.T., Palmer,J.R., Armbruster,D.T., Kuo,Y.-P., Oda,W. and Daniels,C.J. (1995) A rapid procedure for the isolation of RNA from Haloferax volcanii. In Archaea, A Laboratory Manual, Halophiles. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heck C., Rothfuchs,R., Jäger,A., Rauhut,R. and Klug,G. (1996) Effect of the pufQ-pufB intercistronic region on puf mRNA stability in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Microbiol., 20, 1165–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ausubel F.M., Brent,R., Kingston,R.E., Moore,D.D., Seidmann,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (1992) Short protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sistrom W.R. (1977) Transfer of chromosomal genes mediated by plasmid r.68.45 in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 131, 526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tailor D.P., Cohen,S.N., Clark,W.G. and Marrs,B.L. (1983) Alignment of genetic and restriction maps of the photosynthesis region of the Rhodopseudomonas capsulata chromosome by a conjugation-mediated marker rescue technique. J. Bacteriol., 154, 580–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Southern E.M. (1975) Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol., 98, 503–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hitomi M., Nishimura,H., Tsujimoto,Y., Matsui,H. and Watanabe,K. (2003) Identification of a helix-turn-helix motif of Bacillus thermoglucosidasius HrcA essential for binding to the CIRCE element and thermostability of the HrcA-CIRCE complex, indicating a role as a thermosensor. J. Bacteriol., 185, 381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehresmann C., Baudin,F., Mougel,M., Romby,P., Ebel,J.-P. and Ehresmann,B. (1987) Probing the structure of RNAs in solution. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 9109–9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanger F., Nicklen,S. and Coulson,A.R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rauhut R., Jäger,A., Conrad,C. and Klug,G. (1996) Identification and analysis of the rnc gene for RNase III in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1246–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jäger S., Fuhrmann,O., Heck,C., Hebermehl,M., Schiltz,E., Rauhut,R. and Klug,G. (2001) An mRNA degrading complex in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 4581–4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fritsch J., Rothfuchs,R., Rauhut,R. and Klug,G. (1995) Identification of an mRNA element promoting rate-limiting cleavage of the polycistronic puf mRNA in Rhodobacter capsulatus by an enzyme similar to RNase E. Mol. Microbiol., 15, 1017–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hecker M., Schumann,W. and Völker,U. (1996) Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol., 19, 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuker M. (1989) On finding all suboptimal foldings of an RNA molecule. Science, 244, 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaeger J.A., Turner,D.H. and Zuker,M. (1989) Improved predictions of secondary structures for RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 7706–7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpousis A.J., Van Houwe,G., Ehretsmann,C. and Krisch,H.M. (1994) Copurification of E. coli RNAase E and PNPase: evidence for a specific association between two enzymes important in RNA processing and degradation. Cell, 76, 889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee W.T., Terlesky,K.C. and Tabita,F.R. (1997) Cloning and characterization of two groESL operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: transcriptional regulation of the heat-induced groESL operon. J. Bacteriol., 179, 487–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan G. and Wong,S.L. (1995) Regulation of groE expression in Bacillus subtilis: the involvement of the σA-like promoter and the roles of the inverted repeat sequence (CIRCE). J. Bacteriol., 177, 5427–5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segal G. and Ron,E.Z. (1996) Heat shock activation of the groESL operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and the regulatory roles of the inverted repeat. J. Bacteriol., 178, 3634–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nocker A., Hausherr,T., Balsiger,S., Krstulovic,N.-P., Hennecke,H. and Narberhaus,F. (2001) A mRNA-based thermosensor controls expression of rhizobial heat shock genes. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 4800–4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emory S.A. and Belasco,J.G. (1990) The ompA 5′ untranslated segment functions in E. coli as a growth-rate-regulated mRNA stabilizer whose activity is unrelated to transcriptional efficiency. J. Bacteriol., 172, 4472–4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emory S.A., Bouvet,P. and Belasco,J.G. (1992) A 5′-terminal stem-loop structure can stabilize mRNA in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev., 6, 135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackie G.A. (1998) Ribonuclease E is a 5′-end dependent endonuclease. Nature, 395, 720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bechhofer D.H. and Dubnau,D. (1987) Induced mRNA stability in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun F., Hajnsdorf,E. and Régnier,P. (1996) Polynucleotide phosphorylase is required for the rapid degradation of the RNase E processed rpsO mRNA of Escherichia coli devoid of its 3′ hairpin. Mol. Microbiol., 19, 997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Y., Vickers,T.A. and Cohen,S.N. (2002) The catalytic domain of RNase E shows inherent 3′ to 5′ directionality in cleavage site selection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 14746–14751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yura T., Nagai,N. and Mori,H. (1993) Regulation of the heat-shock response in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 47, 321–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]