Abstract

AIM: To describe a successful endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biliary drainage technique with high success and low complication rates.

METHODS: The recorded data of consecutive patients who presented to Siriraj Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Center, Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand for treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice but failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and underwent subsequent EUS-guided biliary drainage were retrospectively reviewed. The patients’ baseline characteristics, clinical manifestations, procedure details, and post-procedure follow-up data were recorded and analyzed. Clinical outcomes were assessed by physical exam and standard laboratory tests. Technical success of the procedure was defined as completion of the stent insertion. Clinical success was defined as improvement of the patient’s overall clinical manifestations, in terms of general well-being evidenced by physical examination, restoration of normal appetite, and adequate biliary drainage. Overall median survival time was calculated as the time from the procedure until the time of death, and survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method. The Student’s t-test and the χ2 test were used to assess the significance of inter-group differences.

RESULTS: A total of 21 cases were enrolled, a single endoscopist performed all the procedures. The mean age was 62.8 years (range: 46-84 years). The sex distribution was almost equal, including 11 women and 10 men. Patients with failed papillary cannulation (33.3%), duodenal obstruction (42.9%), failed selective cannulation (19.0%), and surgical altered anatomy (4.8%) were considered candidates for EUS-guided biliary drainage. Six patients underwent EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy and 15 underwent EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy. The technique using non-cauterization and no balloon dilation was performed for all cases, employing the in-house manufactured tapered tip Teflon catheter to achieve the dilation. The technical success and clinical success rates of this technique were 95.2% and 90.5%, respectively. Complications included bile leakage and pneumoperitoneum, occurred at a rate of 9.5%. None of the patients died from the procedure. One patient presented with a biloma, a major complication that was successfully treated by another endoscopic procedure.

CONCLUSION: We present a highly effective EUS-guided biliary drainage technique that does not require cauterization or balloon dilation.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, Biliary drainage, Hepaticogastrostomy, Choledochoduodenostomy, Endoscopic ultrasound-guided

Core tip: A total of 21 patients who underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biliary drainage following failure of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography were analyzed. The EUS-guided biliary drainage technique, which does not require cauterization or balloon dilation, was found to be effective and safe. The rates of technical and clinical success were 95.2% and 90.5%, respectively. Complications occurred at a relatively low rate (9.5%) and included bile leakage and pneumoperitoneum. No procedure related deaths occurred during the procedure, hospital recovery, or follow-up period. However, one patient developed the major complication of iatrogenic biloma due to stent mal-position, which was successfully resolved by another endoscopic procedure.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a standard treatment for benign and malignant biliary obstruction. ERCP has a failure rate of about 3%-10% due to a combination of the following factors: improper cannulation due to periampullary diverticulum or anatomical variation, biliary obstruction from impacted large common bile duct stones, tight malignant obstruction, gastrointestinal anatomical changes, surgically altered anatomy or gastroduodenal obstruction[1]. Common management techniques following a failed ERCP include an additional ERCP performed by a more experienced endoscopist or the implementation of alternative methods for biliary decompression such as surgical bypass or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD). PTBD is superior to surgical bypass techniques in terms of morbidity and complications[1-5]. However, PTBD still resulted in complications (9%-30%) and a 2%-15% mortality rate was reported. Furthermore, patients reported symptoms including discomfort, unusual physiology and some limitations of the procedure, especially in patients with large amount of ascites[2,3].

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), a medical procedure in which endoscopy is combined with ultrasound to provide imaging of internal organs, has expanded its therapeutic potential since the invention of the linear-array echoendoscope. EUS guided biliary access (EUS guided cholangiography) was first reported by Wiersema et al[6], followed by EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CD) by Giovannini et al[7], and lastly EUS guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HG) was introduced by Burmester et al[8]. There have been many reports regarding the efficacy, safety and feasibility of EUS guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD)[9-24]. The two most common EUS-BD procedures are EUS-CD and EUS-HG[2-10]. Both procedures are initiated by identifying and targeting the biliary tract, followed by puncturing the bile duct depended on the location of obstruction and the reasons for performing drainage, manipulating the guidewire, dilating the created tract, and placing the stent. The success rate of EUS-BD was is 72%-98% while the complication rate is 15%-35%, with complications such as peritonitis and bile leakage being fatal[9-16]. The details of different endoscopic techniques, instruments and accessories used in the procedures are described elsewhere[17-19]. Reasonably, the most important issue for high success and low complication rate of EUS-BD is an appropriate technique for biliary access. The techniques for biliary access were classified into two groups, cauterized or non-cauterized, while the dilation maneuver was also classified as graded dilation or balloon dilation. At present, there are no data directly comparing these two methods. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the techniques for EUS-BD used in our institute, which provided good clinical outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed data from patients with advanced malignant bile duct obstruction who failed ERCP and underwent EUS-guided biliary drainage in our institute from October 2010 to July 2012. The medical records and electronic based medical records were reviewed. Prachayakul V was the endoscopist who performed all the procedures. We analyzed the following clinical outcomes during the follow-up period: patient demographic data, baseline clinical characteristics, indications for EUS-BD, procedure details, and clinical and laboratory results. We defined clinical outcomes using several different criteria. Technical success was defined as the ability to complete the procedure until stent insertion. Clinical success was defined as the improvement of the overall clinical manifestations of the patients in terms of clinical well-being, loss of appetite, and adequate biliary drainage. Adequate biliary drainage was defined as the reduction of total bilirubin more than 50% of pre-treatment bilirubin. Median survival time was defined as the time from the procedure until the time of death. While most patients experiencing complications were followed-up until they passed away, some were contacted telephonically in order to obtain any missing or additional information related to specific complications.

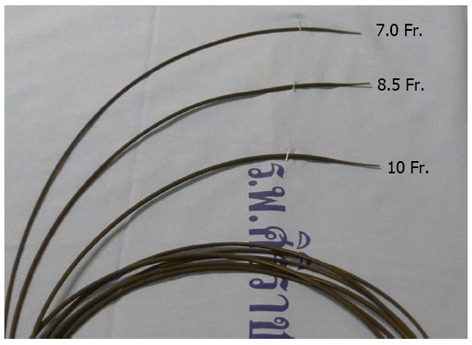

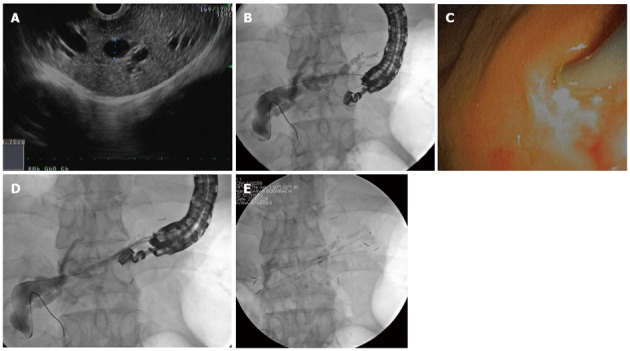

All participating patients gave written informed consent. The procedures were performed in the endoscopic suite at the Siriraj Hospital’s Endoscopy Center with propofol administered total intravenous anesthesia. Patients were positioned in left lateral decubitus, with the punctured site chosen depending on the site of biliary obstruction. The site was chosen after EUS survey, EUS-CD for distal biliary obstruction and EUS-HG for hilar obstruction. Curvilinear echoscope (GF UC-140P, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used in all cases. Either the common bile duct or the intrahepatic bile duct was punctured by using 19-gauge needle (EchoTip® Ultra, Cook Ireland, Limerick, Ireland) and bile was aspirated to confirm the correct position. Contrast medium was injected to get more cholangiography details. The 0.035 jag wire was inserted through a channel in the intrahepatic bile duct and then the tapered tip Teflon catheters which were made by the author (Aswakul P) (Figure 1) were used for graded dilatation starting from 7 or 8.5 up to 10 Fr in diameter. Next, the fully covered self-expandable metal stent (FCSEMS) with varying sizes (60, 80 or 100 mm) were inserted depending on the location of EUS-BD. We generally used FCSEMS size 60 mm in diameter for EUS-CD and 80-100 mm for EUS-HG. All the procedures were done under fluoroscopic monitoring. The positions of the stents were checked and the bleeding was secured. Patients were observed in the recovery room for 1-2 h and transferred to the regular ward care. Most achieved uneventful discharge within 3-5 d after the procedure. Due to awareness of the positions of the stents and stent shortening, abdominal X-rays were done in all patients within 48-72 h. The patients’ physical examination, laboratory tests, and clinical status were recorded. The procedure sequence is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Self-made tapered tip Teflon catheters.

Figure 2.

The procedure sequence. A: Endosonographic view of dilated intra hepatic duct; B: Endoscopic ultrasound guided cholangiography; C: Endoscopic view showing dilatation using tapered tip Teflon catheter; D: Fluoroscopic view showing dilatation tapered tip Teflon catheter; E: Post self-expandable metal stent insertion.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 13.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Overall median survival time was evaluated from the time of procedure until the time of death. The data was analyzed using survival analysis with the Kaplan-Meier method. The descriptive data were reported as mean ± SD and percentage. The Student’s t-test and the χ2 test were used to assess the inter-group differences according to the clinical data. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 21 patients were enrolled in the present study. The mean age was 62.8 years (range 46-84 years), and ten were men (47.6%). The most common diagnoses were advanced pancreatic cancer (45.5%), cholangiocarcinoma (18.2%), gallbladder cancer (18.2%) and others (18.1%). The most common clinical manifestation was obstructive jaundice, which occurred in 86.4% of patients. The mean pre-treatment total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level were 18.1 ± 7.9 mg/dL, 716.5 ± 395.6 IU/mL and 242.0 ± 325.6 IU/mL respectively. The indications for EUS-BD were failed papillary cannulation (33.3%), duodenal obstruction (42.9%), failed selective cannulation (19.0%) and surgical altered anatomy (4.8%). Six patients underwent EUS-CD while another 15 patients underwent EUS-HG. One patient underwent the procedure twice due to a first time technical failure where during guide wire manipulation the wire slipped out and bile leakage occurred. This event led to reduction of intrahepatic duct size and it was too small for puncturing. The patient underwent another procedure two weeks later and achieved successful biliary drainage. Therefore, only 21 patients would be analyzed for clinical outcomes following treatment.

There were immediate complications reported in two cases (9.5%); a case of pneumoperitoneum related with neotract creation and dilation technique that recovered after conservative treatment and another case of bile leakage. Here, a 53-year-old female who had a known case of advanced cholangiocarcinoma and underwent EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy, showed higher level of bilirubin within 2 wk after stent insertion due to malposition of the stent. The stent was slipped out of the gastric wall causing acute angulation at hepatogastric site that occurred during stent deployment and led to biloma formation. The patient was managed conservatively without surgery because there was no evidence of clinical peritonitis. A computed tomography scan was done 10 d later and revealed biloma at the intraperitoneum site of the stent. The patient underwent EUS-guided biloma drainage and passed away one month later due to disease progression.

Technical success occurred in 95.5% of patients while clinical success was achieved in 90.5%. Adequate biliary drainage was achieved in 85.7% of the patients within two weeks except only one case where drainage did not occur until the fourth week after the procedure. There were two patients who did not benefit from the drainage procedures; the first case showed no improvement of bilirubin level after the stent insertion due to liver failure from massive liver metastasis and a case of bile leakage where the patient eventually died due to disease progression. The median survival of the patients in this series was 93 d. There were three patients still alive at the time that we finished the study.

DISCUSSION

The result of EUS-BD in the present study was similar to previous case reports in terms of technical and clinical success, at about 75.0%-96.5%[1-13]. However the complications found in this series were lower than those reported in other studies[16-29]. More than 90% of the patients were clinically improved after the procedures even though the median survival time was only 93 d. Most patients passed away because of advancement of the primary malignancy. Regarding of the complications occurring with EUS-BD technique that we used in this study, only one case (4.8%) related with neotract creation and dilation technique. We did not use cauterization because we hypothesized that it might cause more tissue injury and is technically dangerous, especially when the tip of the knife was not in the appropriate position. Difficulty inserting the catheter was overcome by using a self-made Teflon catheter with a small the tapered tip diameter (as small as the 0.035 guidewire). We also chose to not use the balloon dilatation technique to create the neo-tract that was slightly larger than the size of the introducer of the SEMS. This worked to minimize the risk of bile leakage and symptomatic gastric perforation. Further, we found this technique was feasible and easy to perform because of the specific characteristic of dilator tip. While a potential challenge to this technique is the need for more frequent guidewire exchange, the presence of a well-trained assistant allowed us to complete the procedure without encountering any problems. While we did encounter some bile leakage, it was due to a mistake during SEMS deployment, not during the neotract creation and dilation. Fortunately, because of smaller dilated tract, the SEMS did not immediately expand, so the bile leakage in this particular case was minimal and gradually occurred leading only to a localized formation of biloma without peritonitis. Another complication of EUS-BD was early stent migration. This led to peritonitis, but was corrected by surgery[30]. We did not experience this complication because the SEMS did not immediately over-expanded due to the smaller diameter of the neo-tract. This made the SEMS fit the tract appropriately under good radial SEMS force, and the tract was slowly formed and fully expanded by 72 h[31]. This technique also minimized the risk of early stent migration. We had four cases of late stent migration (partial migration) when the tract was already well formed four to eight weeks after the procedure and thus no morbidity was found. Consistent with findings of Park et al[1], the only one risk factor associated with postprocedure adverse events in performing EUS-BD was the use of a needle knife for fistula tract creation. This study did have some limitations. First, although the tapered tip Teflon catheter used in this case series were very unique, the small sample size may not be reproducible. Second, this was the retrospective review of the data. Therefore, multi-center, larger population, prospective studies should be conducted in the future.

We have reported a technique for EUS-guided biliary drainage that does not use cauterization or balloon dilation. The technique was highly effective with a low complication rate, and has not been previously reported.

COMMENTS

Background

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) is a novel alternative treatment for the approximately 3%-10% of patients who fail standard endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP). Techniques for biliary access and drainage were reported in recent years, however there was no data indicating which one is the best technique for minimizing complications and increasing the success.

Research frontiers

This was a retrospective study of 21 patients with advanced malignant bile duct obstruction who failed ERCP and underwent EUS-guided biliary drainage. The techniques used in this case series created the hepaticogastrostomy and choledochoduodenostomy tract in the absence of cauterization and balloon dilatation. Tapered tip Teflon catheters were used for dilation. The procedure had very high technical (95.2%) and clinical (90.5%) success, while maintaining lower complication rates (9.5%) when compared to other studies (15%-35%).

Innovations and breakthroughs

The goal of this study was to demonstrate another option for EUS-guided biliary drainage that used novel instruments and techniques resulting in an enhanced success rate and a decreased complication rate.

Applications

This novel EUS-guided biliary drainage technique could be widely used as a safer and more effective alternative to cauterization or balloon dilation techniques that are widely used currently.

Terminology

EUS-BD is a novel alternative treatment for patients who suffered from biliary obstruction and failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The most common procedures are EUS guided hepaticogastrostomy and EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy. Regarded as a less invasive procedure when comparing to surgical bypass with a complication rate of 15%-35%, it becomes a preferable treatment option in some particular patients.

Peer review

This was an interesting case series that demonstrated alternative treatment options and techniques for endoscopic ultrasound guided-biliary drainage in patients with advanced malignant bile duct obstruction who failed conventional biliary drainage techniques.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Figueiredo P, Jadallah K S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Park do H, Jang JW, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1276–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attasaranya S, Netinasunton N, Jongboonyanuparp T, Sottisuporn J, Witeerungrot T, Pirathvisuth T, Ovartlarnporn B. The Spectrum of Endoscopic Ultrasound Intervention in Biliary Diseases: A Single Center’s Experience in 31 Cases. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:680753. doi: 10.1155/2012/680753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy MJ. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound for biliary and pancreatic disorders. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TH, Kim SH, Oh HJ, Sohn YW, Lee SO. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage with placement of a fully covered metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2526–2532. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Umeda J, Moriyasu F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:611–616. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiersema MJ, Sandusky D, Carr R, Wiersema LM, Erdel WC, Frederick PK. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:102–106. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(06)80108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannini M, Bories E. EUS-Guided Biliary Drainage. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:348719. doi: 10.1155/2012/348719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burmester E, Niehaus J, Leineweber T, Huetteroth T. EUS-cholangio-drainage of the bile duct: report of 4 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:246–251. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irisawa A, Hikichi T, Shibukawa G, Takagi T, Wakatsuki T, Takahashi Y, Imamura H, Sato A, Sato M, Ikeda T, et al. Pancreatobiliary drainage using the EUS-FNA technique: EUS-BD and EUS-PD. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:598–604. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarantino I, Barresi L, Fabbri C, Traina M. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:306–311. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i7.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chavalitdhamrong D, Draganov PV. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:491–497. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamao K, Hara K, Mizuno N, Sawaki A, Hijioka S, Niwa Y, Tajika M, Kawai H, Kondo S, Shimizu Y, et al. EUS-Guided Biliary Drainage. Gut Liver. 2010;4 Suppl 1:S67–S75. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.S1.S67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee KH, Lee JK. Interventional endoscopic ultrasonography: present and future. Clin Endosc. 2011;44:6–12. doi: 10.5946/ce.2011.44.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Artifon EL, Takada J, Okawa L, Ferreira F, Santos M, Moura EG, Otoch JP, Sakai P. Successful endoscopic ultrasound-guided overstenting biliary drainage through a pre-existing proximal migrated metal biliary stent. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2011;76:270–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholangiopancreatography and rendezvous techniques. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwashita T, Lee JG, Shinoura S, Nakai Y, Park DH, Muthusamy VR, Chang KJ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous for biliary access after failed cannulation. Endoscopy. 2012;44:60–65. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramírez-Luna MA, Téllez-Ávila FI, Giovannini M, Valdovinos-Andraca F, Guerrero-Hernández I, Herrera-Esquivel J. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliodigestive drainage is a good alternative in patients with unresectable cancer. Endoscopy. 2011;43:826–830. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamao K, Bhatis V, Mizuno N, Sawaki A, Ishikawa H, Tajika M, Hoki N, Shimizu Y, Fukami N. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for palliative biliary drainage in the patients with malignent biliary obstruction: results of long term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2008;40:340–342. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shami VM, Talreja JP, Mahajan A, Phillips MS, Yeaton P, Kahaleh M. EUS-guided drainage of bilomas: a new alternative? Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hara K, Yamao K, Niwa Y, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Hijioka S, Tajika M, Kawai H, Kondo S, Kobayashi Y, et al. Prospective clinical study of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant lower biliary tract obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1239–1245. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarantino I, Barresi L. Interventional endoscopic ultrasound: Therapeutic capability and potential. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;1:39–44. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v1.i1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn JY, Seo DW, Eum J, Song TJ, Moon SH, Park do H, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH. Single-Step EUS-Guided Transmural Drainage of Pancreatic Pseudocysts: Analysis of Technical Feasibility, Efficacy, and Safety. Gut Liver. 2010;4:524–529. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Súbtil JC, Betes M, Muñoz-Navas M. Gallbladder drainage guided by endoscopic ultrasound. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:203–209. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i6.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Kato Y, et al. Endosonography-guided biliary drainage with one-step placement of a newly developed fully covered metal stent followed by duodenal stenting for pancreatic head cancer. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2010;2010:426534. doi: 10.1155/2010/426534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, Bhat YM, Nguyen-Tang T, Shaw RE, Binmoeller KF. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Fuccio L, Polifemo AM, Ferrara F, Ghersi S, Bassi M, Billi P, Maimone A, Cennamo V, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with placement of a new partially covered biliary stent for palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: a case series. Endoscopy. 2011;43:438–441. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiersema MJ, Sandusky D, Carr R, Wiersema LM, Erdel WC, Frederick PK. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:102–106. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(06)80108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sreenarasimhaiah J. Interventional endoscopic ultrasound: the next frontier in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:319–324. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181a44405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddiqui AA, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Lara LF, Harford W, Lee C, Eloubeidi MA. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transduodenal placement of a fully covered metal stent for palliative biliary drainage in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:549–555. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belletrutti PJ, DiMaio CJ, Gerdes H, Schattner MA. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage in patients with unapproachable ampullae due to malignant duodenal obstruction. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2011;42:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen-Tang T, Binmoeller KF, Sanchez-Yague A, Shah JN. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transhepatic anterograde self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) placement across malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2010;42:232–236. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]