Abstract

AIM: To investigate the learning curve of transumbilical suture-suspension single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC).

METHODS: The clinical data of 180 consecutive transumbilical suture-suspension SILCs performed by a team in our department during the period from August 2009 to March 2011 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were divided into nine groups according to operation dates, and each group included 20 patients operated on consecutively in each time period. The surgical outcome was assessed by comparing operation time, blood loss during operation, and complications between groups in order to evaluate the improvement in technique.

RESULTS: A total of 180 SILCs were successfully performed by five doctors. The average operation time was 53.58 ± 30.08 min (range: 20.00-160.00 min) and average blood loss was 12.70 ± 11.60 mL (range: 0.00-100.00 mL). None of the patients were converted to laparotomy or multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There were no major complications such as hemorrhage or biliary system injury during surgery. Eight postoperative complications occurred mainly in the first three groups (n = 6), and included ecchymosis around the umbilical incision (n = 7) which resolved without special treatment, and one case of delayed bile leakage in group 8, which was treated by ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage. There were no differences in intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complications and length of postoperative hospital stay among the groups. Bonferroni’s test showed that the operation time in group 1 was significantly longer than that in the other groups (F = 7.257, P = 0.000). The majority of patients in each group were discharged within 2 d, with an average postoperative hospital stay of 1.9 ± 1.2 d.

CONCLUSION: Following scientific principles and standard procedures, a team experienced in multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy can master the technique of SILC after 20 cases.

Keywords: Single incision laparoscopic surgery, Cholecystectomy, Learning curve, Suture-suspension

Core tip: As a new technology, single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is more difficult to perform than multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy with higher technical demands. Thus, SILC may have a specific learning curve. The present study retrospectively analyzed the surgical outcomes of transumbilical suture-suspension SILC performed by the same team in our department to investigate the learning curve of this technology, thereby guiding the surgeons to pass the initial learning period smoothly, safely, and quickly.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become widely accepted and is considered the gold standard for the treatment of benign gallbladder diseases. With continuous development in techniques and devices, laparoscopy has moved in the direction of minimally invasive surgery in order to meet patients’ cosmetic requirements, i.e., from a four-port conventional laparoscope to three-port, two-port, and the present transumbilical single-port. As a new technology, single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is more difficult to perform than multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy with higher technical demands. Thus, SILC may have a specific learning curve. The present study retrospectively analyzed the surgical outcomes of transumbilical suture-suspension SILC performed by the same team in our department to investigate the learning curve of this technology, thereby guiding the surgeons to pass the initial learning period smoothly, safely, and quickly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General information

During the period from August 2009 to March 2011, 180 patients received transumbilical SILCs in our department, including 78 males and 102 females, with an average age of 48.7 ± 13.0 years (range: 18.0-79.0 years). All patients had agreed to receive SILC, and for this study the records were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were eligible for SILC if they met the following criteria: (1) clinical diagnosis of symptomatic gallstones, gallbladder polyps, with acute cholecystitis (less than 72 h); and (2) ability to tolerate the procedure without a functional failure in important organs including the lungs, heart, liver and kidneys. Patients were considered ineligible if they had an American Society of Anesthesiologists score > 3 or were unable to tolerate general anesthesia due to other reasons, suspected gallbladder malignancy, and a history of recent upper abdominal surgery.

All operations were completed by the same surgical team. The principal surgeons were both hepatobiliary surgeons with 10 or more years of clinical experience, and had independently performed more than 500 consecutive cases of multiple-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The assistants were senior residents who had laparoscopic training on virtual or animal models in the training centre.

The 180 patients were divided evenly into 9 groups according to the time period they received surgery (20 patients in each period). Clinical data collected included patient name, gender, age, primary diagnosis, and previous abdominal surgery history. The difference in operation time, the amount of blood loss during the operation and postoperative complications in all groups were analyzed and compared.

Surgical procedure

The procedure has been described previously[1]. In summary, a single, curved 1.5-cm incision was made below the umbilicus and a Veress needle was inserted followed by the creation of a pneumoperitoneum which was maintained at 13 mmHg. An 11-mm trocar was inserted as the port for a 30° laparoscope at the left side of the incision. A 5-mm trocar was inserted as a manual port at the right side of the incision. The tissues between the two ports were kept to prevent gas leakage. Two size 7-0 silk threads were placed through the tissues on the bottom of the gallbladder and the muscular layer of the ampulla, respectively, and then pulled out through the abdominal wall in order to fully expose the cystic duct and the gallbladder triangle. After the gallbladder triangle was dissected using an ultrasonic scalpel, the cystic duct was clipped with titanium clips and excised. Next, the whole gallbladder was isolated, dissected, and extracted through the umbilical incision. Careful control of homeostasis and bile leakage was achieved. The abdominal cavity was then rinsed, the pneumoperitoneum was released and the incision was closed.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test, and quantitative data was analyzed by the χ2 test. SPSS 15.0 software was used for statistical analysis, and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic data

Of the 180 patients enrolled, 78 were men and 102 were women. The average age was 48.7 ± 13.0 years (range: 18.0-79.0 years). The mean body mass index was 23.31 ± 2.83 kg/m2 (range: 16.35-29.36 kg/m2). Among these 180 patients, 17 had a history of abdominal surgery, 11 of whom had undergone open procedures, including appendectomy (n = 5), cesarean section (n = 4), total hysterectomy (n = 1) and bilateral tubal ligation (n = 1); the other six candidates had undergone laparoscopic appendectomy (n = 4) and laparoscopic herniorrhaphy (n = 2) (Table 1). The nine groups were similar with respect to sex, age, body mass index and previous history of abdominal surgery (Table 2)

Table 1.

General data

| SILCs (n = 180) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 78 | |

| Female | 102 | |

| Age (yr) | 48.7 ± 13.0 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.31 ± 2.83 | |

| Previous history of abdominal surgery | ||

| Yes | 5 appendectomy | 4 laparoscopic appendectomy |

| 4 cesarean sections | 2 laparoscopic herniorrhaphy | |

| 1 total hysterectomy | ||

| 1 bilateral tubal ligation | ||

| No | 163 | |

SILC: Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; BMI: Body mass index.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Groups | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | F | P |

| Age (yr)12 | 47.7 ± 10.8 | 45.1 ± 13.8 | 50.4 ± 14.1 | 50.0 ± 11.7 | 49.4 ± 13.8 | 52.7 ± 14.5 | 52.9 ± 12.0 | 46.9 ± 14.3 | 43.7 ± 11.2 | 1.2082 | 0.297 |

| Gender (M/F)3 | 11/9 | 7/13 | 9/11 | 6/14 | 5/15 | 11/9 | 9/11 | 7/13 | 13/7 | 11.343 | 0.183 |

| Previous history of abdominal surgery3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6.333 | 0.610 |

| BMI (kg/m2)12 | 23.11 ± 2.86 | 23.96 ± 3.49 | 22.31 ± 2.99 | 23.83 ± 3.28 | 23.75 ± 2.28 | 22.96 ± 2.41 | 24.26 ± 2.76 | 22.80 ± 2.16 | 22.85 ± 2.89 | 1.0752 | 0.383 |

Values are mean ± SD;

One-way ANOVA;

χ2 test. BMI: Body mass index; M/F: Male/female.

Clinical outcomes

All patients underwent successful SILC, and no patient required conversion to standard LC or open surgery. The average operative time was 53.58 ± 23.44 min (range: 20-160 min) and the average blood loss during surgery was 12.7± 11.6 mL (range: 0-100 mL). There was no intraoperative abdominal organ damage or complications such as hemorrhage or biliary system injury during surgery. Eight postoperative complications occurred, mainly in the first three groups (n = 6), and included ecchymosis around the umbilical incision (n = 7) which resolved without special treatment, and one case of delayed bile leakage in group 8, which was treated by ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage. The majority of patients in each group were discharged within 2 d, with an average postoperative hospital stay of 1.9 ± 1.2 d. There were no differences in intraoperative blood loss and postoperative complications among the groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Surgical data

| Overall | Group 15 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 | Group 7 | Group 8 | Group 9 | |

| Surgery time14 | 53.58 ± 30.08 | 82.45 ± 23.442 | 59.00 ± 25.47 | 58.50 ± 21.16 | 55.00 ± 17.77 | 49.50 ± 12.45 | 45.50 ± 20.22 | 44.75 ± 18.67 | 45.25 ± 17.95 | 42.25 ± 13.52 |

| Blood loss1 | 12.70 ± 11.60 | 16.65 ± 9.96 | 12.55 ± 13.45 | 14.05 ± 14.55 | 13.70 ± 9.76 | 12.90 ± 12.01 | 11.60 ± 12.31 | 12.70 ± 12.23 | 11.60 ± 11.10 | 10.55 ± 9.83 |

| Complications3 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

One-way ANOVA;

Values are mean ± SD;

χ2 test;

Comparisons between groups were performed using ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test;

The operation time in group 1 was significantly longer than that in the other groups (F = 7.257, P = 0.000).

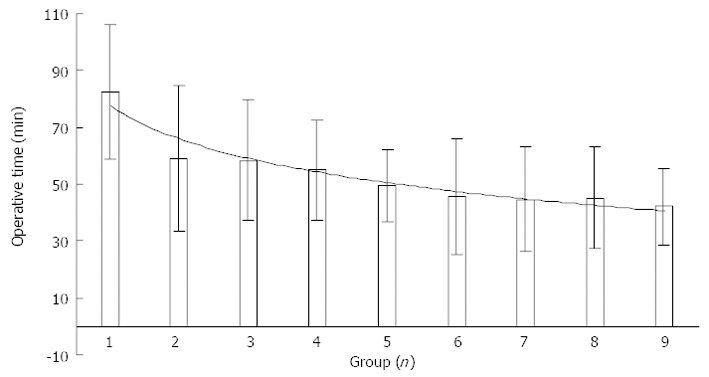

Bonferroni’s test showed that the operation time in group 1 was significantly longer than that in the other groups (F = 7.257, P = 0.000). No differences were found following comparisons within the other groups (P ≥ 0.05). The standard deviation of operative time was 30.1 min in group 1, and gradually declined and stabilized from group 2 to group 9 (Figure 1). The blood loss in group 1 was 16.65 ± 9.96 mL, which was greater than that in the other groups, however, the difference was not statistically significant (F = 2.130, P = 0.082, Table 3).

Figure 1.

The changes in operation time.

DISCUSSION

Single-incision laparoscopy is a new technique, which has evolved due to the recent development of minimally invasive surgery. This technique has been applied in hepatobiliary surgery[1-8], general surgery[9-12], urological surgery[13-17], gynecology and obstetrics[18,19], and other areas. Of these, SILC is the most widely used and sophisticated technique. Some researchers believe that it has the potential to replace multi-port laparoscopic techniques and become the gold standard for cholecystectomy[20-22]. Compared with multi-port laparoscopy, single-incision laparoscopic surgery has unique features. First, it requires the operator to have a comprehensive knowledge of in vivo micro-anatomy and three-dimensional sensibility in order to compensate for limited surgical fields. Second, it requires skillful techniques and clear procedure understanding to replace the sense of hand touch. Finally, it requires good team work and appropriate surgical devices to compensate for interference between instruments. For these reasons, operators in the early stage of training will inevitably experience a process of exploration and skill acquisition, and this process is the learning curve of single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

A learning curve is usually evaluated by the number of surgeries required to progress from an initial to a skilled state. After completing a certain number of operations, a surgeon’s skill will be improved significantly and they will be competent in the surgical procedure and able to manage complications skillfully. At this stage, the learning curve is complete and the learning plateau is reached[23]. The criteria for evaluating the skillfulness of performing SILC are operative time, blood loss during the operation, and complications including bile leakage and wound infection.

The change in operation time is the most direct and accurate indicator reflecting the learning curve, because it reflects a surgeon’s mastery of the technique. Operation time is influenced by four main factors, including operator skill, surgical concepts, the cooperation of the surgical team, and the choice of surgical devices. In order to use operation time as an indicator of skill, we chose a team with experience in conventional laparoscopic surgery and used the same set of surgical devices to complete the surgeries in this study. Therefore, the impact of different teams and surgical devices on operation time were minimized as much as possible.

Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been incorporated into national standards for the quality control of single disease, and the procedures are standardized. Once patients were recruited into this study, the operation was performed using a standard procedure, and the difference resulting from variation in surgical concepts was excluded. In this study, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test were performed for multiple statistical comparisons. The advantage of Bonferroni’s test is that it is a simple and conservative method to control type I error. We found that the decrease in operation time was significant from group 1 to group 2, and was relatively stable from group 2 to group 9; thus, the number of cases in group 1 reflects the learning curve. The fluctuation in operation time was greatest in group 1, indicating that in the first 20 cases the surgical technique was not standardized and the stability of technique was poor. As shown in Figure 1, the operation time continuously decreased and the shortest operation time was 20 min, suggesting that after continuous learning and training it is possible to improve the technique.

Patients recruited for SILC in the early period were carefully selected. Even so, blood loss in group 1 was greater than that in the other groups, but without statistical significance. After the first 20 cases, the average blood loss decreased rapidly and gradually stabilized. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of complications and duration of hospitalization, suggesting that in the early period the operation was carried out very carefully and successfully. In all 180 patients, the outcomes were satisfactory and no patients required conversion to laparotomy or multi-port laparoscopy, and no patients required additional surgery. These results indicate that SILC is safe and feasible when performed by surgeons who are experienced in multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The circumstances are different in different medical centers and endoscopy teams, thus, the surgical experience and concepts would also be different. As a result, the learning curves for SILC would be different[23-26]. Our results showed a rapid decline in operation time in the early period, and a slow stabilizing, declining curve in the late period, demonstrating that the learning curve was approximately 20 cases. That is, surgeons who are experienced in multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy are likely to pass the learning curve smoothly and safely after performing 20 cases of SILC.

COMMENTS

Background

The potential benefits of single-incision laparoscopic technology include reduced postoperative pain, improved cosmetic result and earlier return to normal life. Some investigators have predicted that single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) may become an alternative standard approach for benign gallbladder diseases. However, there is still controversy with regard to its safety and reproducibility as SILC is more difficult to perform than multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy with higher technical demands.

Research frontiers

SILC is a rapidly advancing technique in laparoscopic surgery. However, there is limited evidence on the learning curve and practicality of performing this procedure. The present study retrospectively analyzed the surgical outcomes of transumbilical suture-suspension SILC performed by the same team in our department to investigate the learning curve of this technology, thereby guiding the surgeons to pass the initial learning period smoothly, safely, and quickly.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is a large-scale retrospective study to explore the safety and reproducibility of SILC for the management of benign gallbladder diseases in selected patients.

Applications

The results confirmed that SILC was a safe and effective method for treating benign gallbladder diseases. There was a rapid decline in operation time in the early period, and a slow stabilizing, declining curve in the late period, demonstrating that the learning curve was approximately 20 cases. That is, surgeons who are experienced in multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy are likely to pass the learning curve smoothly and safely after performing 20 cases of SILC.

Terminology

SILC is a minimally invasive surgical procedure in which cholecystectomy is accomplished exclusively through a single 15-25 mm incision in the patient’s navel. Unlike the traditional multi-port laparoscopic approach, SILC leaves only a single small scar in the navel.

Peer review

This is an interesting article, which presents a series of SILC procedures. The study does demonstrate that there is learning curve for SILC.

Footnotes

Supported by Science and Technology Projects of Haizhu District of Guangzhou, China, No. 2012-cg-26

P- Reviewers Leitman IM, Meshikhes AW, Rodriguez DC, Vettoretto N S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Jiang ZS, Cheng Y, Xu XP, Zhang Z, He GL, Xu TC, Zhou CJ, Qin JS, Liu HY, Gao Y, et al. [Comparison of operative techniques in single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: suture-suspension versus three-device method] Zhonghua Yi Xue Zazhi. 2013;93:455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaujoux S, Kingham TP, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica MI, Allen PJ, Fong Y. Single-incision laparoscopic liver resection. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1489–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantke R, Wicht S. Single-port liver cyst fenestration combined with single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy using completely reusable instruments. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:e28–e30. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181cdf19f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Podolsky ER, Rottman SJ, Poblete H, King SA, Curcillo PG. Single port access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a completely transumbilical approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:219–222. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misawa T, Sakamoto T, Ito R, Shiba H, Gocho T, Wakiyama S, Ishida Y, Yanaga K. Single-incision laparoscopic splenectomy using the “tug-exposure technique” in adults: results of ten initial cases. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3222–3227. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1697-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi M, Kurhade S, Peethambaram MS, Kalghatgi S, Narsimhan M, Ardhanari R. Single-incision laparoscopic splenectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:65–67. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.72385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curcillo PG, Wu AS, Podolsky ER, Graybeal C, Katkhouda N, Saenz A, Dunham R, Fendley S, Neff M, Copper C, et al. Single-port-access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional report of the first 297 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1854–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan M, Jiang Z, Cheng Y, Xu X, Zhang Z, Zhou C, He G, Xu T, Liu H, Gao Y. Single-incision laparoscopic hepatectomy for benign and malignant hepatopathy: initial experience in 8 Chinese patients. Surg Innov. 2012;19:446–451. doi: 10.1177/1553350612438412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Froghi F, Sodergren MH, Darzi A, Paraskeva P. Single-incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS) in general surgery: a review of current practice. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:191–204. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181ed86c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano Y, Watanabe T, Uchida T, Yoshida S, Kato H, Hosokawa O. Laparoendoscopic single site partial resection of the stomach for gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:262–264. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181e36a5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidal O, Valentini M, Ginestà C, Martí J, Espert JJ, Benarroch G, García-Valdecasas JC. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:686–691. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang G, Liu S, Yu W, Wang L, Liu N, Li F, Hu S. Gasless laparoendoscopic single-site surgery with abdominal wall lift in general surgery: initial experience. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:298–304. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Symes A, Rane A. Urological applications of single-site laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:90–95. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.72394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leppert JT, Breda A, Harper JD, Schulam PG. Laparoendoscopic single-site porcine nephrectomy using a novel valveless trocar system. J Endourol. 2011;25:119–122. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almeida GL, Lima NG, Schmitt CS, Kaouk JH, Teloken C. [Transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic ureterolithotomy] Actas Urol Esp. 2011;35:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg MS, Cadeddu JA, Desai MM. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery in urology. Curr Opin Urol. 2010;20:141–147. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833625a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irwin BH, Rao PP, Stein RJ, Desai MM. Laparoendoscopic single site surgery in urology. Urol Clin North Am. 2009;36:223–35, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fader AN, Levinson KL, Gunderson CC, Winder AD, Escobar PF. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery in gynaecology: A new frontier in minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:71–77. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.72387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escobar PF, Bedaiwy MA, Fader AN, Falcone T. Laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) surgery in patients with benign adnexal disease. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2074.e7–2074.10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph S, Moore BT, Sorensen GB, Earley JW, Tang F, Jones P, Brown KM. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparison with the gold standard. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3008–3015. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philipp SR, Miedema BW, Thaler K. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy using conventional instruments: early experience in comparison with the gold standard. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:632–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan MX, Jiang ZS, Cheng Y, Xu XP, Zhang Z, Qin JS, He GL, Xu TC, Zhou CJ, Liu HY, et al. Single-incision vs three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: prospective randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:394–398. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i3.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez J, Ross S, Morton C, McFarlin K, Dahal S, Golkar F, Albrink M, Rosemurgy A. The learning curve of laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) cholecystectomy: definable, short, and safe. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon D, Bell RL, Duffy AJ, Roberts KE. Single-port cholecystectomy: small scar, short learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2954–2957. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu Z, Sun J, Pu Y, Jiang T, Cao J, Wu W. Learning curve of transumbilical single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILS): a preliminary study of 80 selected patients with benign gallbladder diseases. World J Surg. 2011;35:2092–2101. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kravetz AJ, Iddings D, Basson MD, Kia MA. The learning curve with single-port cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2009;13:332–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]