Abstract

AIM: To investigate stepwise sedation for elderly patients with mild/moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) during upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

METHODS: Eighty-six elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD and 82 elderly patients without COPD scheduled for upper GI endoscopy were randomly assigned to receive one of the following two sedation methods: stepwise sedation involving three-stage administration of propofol combined with midazolam [COPD with stepwise sedation (group Cs), and non-COPD with stepwise sedation (group Ns)] or continuous sedation involving continuous administration of propofol combined with midazolam [COPD with continuous sedation (group Cc), and non-COPD with continuous sedation (group Nc)]. Saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2), blood pressure, and pulse rate were monitored, and patient discomfort, adverse events, drugs dosage, and recovery time were recorded.

RESULTS: All endoscopies were completed successfully. The occurrences of hypoxemia in groups Cs, Cc, Ns, and Nc were 4 (9.3%), 12 (27.9%), 3 (7.3%), and 5 (12.2%), respectively. The occurrence of hypoxemia in group Cs was significantly lower than that in group Cc (P < 0.05). The average decreases in value of SpO2, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure in group Cs were significantly lower than those in group Cc. Additionally, propofol dosage and overall rate of adverse events in group Cs were lower than those in group Cc. Finally, the recovery time in group Cs was significantly shorter than that in group Cc, and that in group Ns was significantly shorter than that in group Nc (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: The stepwise sedation method is effective and safer than the continuous sedation method for elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD during upper GI endoscopy.

Keywords: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, Adverse events, Sedation, Monitoring, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Core tip: Many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have to undergo upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy because of digestive symptoms. A sedation method specially designed for elderly patients with COPD is urgently needed for use in clinical practice. In this study, we designed a new stepwise sedation method. Eighty-six elderly patients with COPD and 82 elderly patients without COPD scheduled for upper GI endoscopy were randomly assigned stepwise sedation or continuous sedation. The results indicate that the stepwise sedation method is effective and safer than the continuous sedation method for elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD during upper GI endoscopy.

INTRODUCTION

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy is a commonly used interventional examination method for reliable diagnosis of upper GI diseases. The incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Chinese urban populations over 40 years old is 8.2%[1]. Due to tobacco smoking, solid-fuel use, and other reasons, an estimated 65 million people will die of COPD in China between 2003 and 2033[2]. Many patients with COPD have to undergo upper GI endoscopy because of digestive symptoms. Due to inadequate experience with the application of sedation technology during endoscopy in past decades, patients typically underwent routine endoscopic procedures without sedatives, receiving only local pharyngeal lidocaine anesthesia before endoscopy. However, this methodology can lead to various adverse effects, including fear, nausea and vomiting, elevated blood pressure, angina, myocardial infarction, and even death. Moreover, the risk of adverse effects is even greater in elderly patients with cardiopulmonary diseases[3-6]. These issues give rise to patient reluctance to be examined and delay of diagnosis and treatment of alimentary system diseases.

In recent years endoscopy with sedation has become a popular option for both patients and gastroenterologists. Midazolam and propofol are generally used as sedatives during endoscopic procedures[7-10]. However, the use of sedatives during endoscopy in elderly patients with COPD remains controversial because of safety concerns[11]. Compared with younger patients, elderly patients exhibited a significant increase in risk of oxygen saturation below 90% and oxygen saturation decrease more than 5%[12]. Moreover, propofol is a potent depressant of airway reflexes at hypnotic concentrations[13]. Elderly patients with COPD usually have cough, phlegm and respiratory insufficiency, and are more likely to experience decreased saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) because of the dysfunction of the cough reflex and respiratory track blockage by phlegm during an endoscopic procedure with sedation. These symptoms commonly lead to a higher risk of adverse events during GI endoscopy. Therefore, a sedation method specially designed for elderly patients with COPD is urgently needed in clinical practice. Most episodes of hypoxemia under sedation occur in the five minute interval following medication administration and/or intubation, and less frequent administration of medications or diligent monitoring during this period might decrease hypoxemia[14].

In this study, we designed a stepwise sedation method that involves three-stage administration of propofol combined with midazolam so that the sedation depth is approached gradually. Through analysis of SpO2, blood pressure, pulse rate, patient discomfort, adverse events, midazolam dosage, propofol dosage, and recovery time; we compared the efficacy and safety of this new method with the continuous sedation method during upper GI endoscopy in elderly patients with and without COPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Eighty-six elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD and 82 elderly patients without COPD (> 70 years old) who underwent diagnostic upper GI endoscopic procedures using sedation at the endoscopic unit of Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University between March 2011 and December 2012 were included in this study. COPD was diagnosed based on the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD[15]. Two hundred sixty-one other patients were excluded because they did not consent to participate (n = 35) or because they had other diseases or excluding conditions (n = 226). These included hypertension (> 140/90 mmHg), hypotension (< 90/60 mmHg), sick sinus syndrome, neurologic or psychiatric disease, metabolic disease, liver/renal insufficiency, severe cough and sputum, SpO2 < 90%, COPD class III/IV, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class IV/V, and drug allergy. Thus, our study focused exclusively on mild/moderate COPD patients.

The eligible participants with and without COPD were randomized into the two treatment groups in equal numbers. Computer-generated randomization blocks were utilized. Sealed envelopes containing the treatment protocol were opened in the procedure room after enrollment in the study.

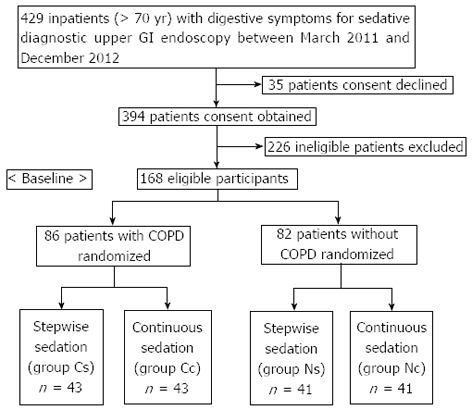

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial, and Table 1 lists data and clinical characteristics of the study population. The differences in COPD and ASA classification between COPD with stepwise sedation (group Cs) and COPD with continuous sedation (group Cc) were not significant, and ASA classification did not differ significantly between non-COPD with stepwise sedation (group Ns) and non-COPD with continuous sedation (group Nc). The differences in other factors among the four groups were not significant. Gastroenterologists with specific expertise in GI endoscopy performed endoscopic procedures, and an anesthetist administered the sedatives. Before the procedure, the participants signed an informed consent form. Our institution’s ethics committee approved this study.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants throughout the trial. GI: Gastrointestinal; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Group Cs: COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Cc: COPD with continuous sedation; Group Ns: Non-COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Nc: Non-COPD with continuous sedation.

Table 1.

Demographic data and clinical characteristics of the study population

| Parameter |

Group |

|||

| Cs (n = 43) | Cc (n = 43) | Ns (n = 41) | Nc (n = 41) | |

| Sex: male/female | 35/8 | 34/9 | 30/11 | 30/11 |

| Age: yr, mean ± SD | 74.5 ± 2.5 | 74.2 ± 2.3 | 77.6 ± 4.6 | 76.7 ± 4.6 |

| (range) | (71-80) | (71-80) | (71-88) | (71-90) |

| Weight: kg, mean ± SD | 56.3 ± 6.4 | 56.8 ± 6.6 | 56.5 ± 7.0 | 57.2 ± 6.5 |

| (range) | (45-70) | (48-71) | (46-73) | (47-71) |

| Alcohol consumption: Y/N | 7/36 | 5/38 | 6/35 | 4/37 |

| Smoking: Y/N | 28/15 | 26/17 | 24/17 | 22/19 |

| COPD classification | ||||

| I | 28 | 30 | ||

| II | 15 | 13 | ||

| ASA classification | ||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 35 | 37 |

| II | 11 | 13 | 6 | 4 |

| III | 32 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| Major endoscopic findings | ||||

| Chronic superficial gastritis | 14 | 11 | 13 | 15 |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Gastric ulcer | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 8 | 7 | 9 | 6 |

| Gastric cancer | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Gastric polyp | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Esophagus cancer | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

Group Cs: COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Cc: COPD with continuous sedation; Group Ns: Non-COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Nc: Non-COPD with continuous sedation; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiology; Y/N: Yes/no.

Sedation procedure

All patients were given lidocaine via throat spray before the endoscopic procedure and received nasal oxygen insufflations at a rate of 2 L/min during the endoscopy. Both stepwise and continuous methods of sedation were used.

For the stepwise sedation (groups Cs and Ns), the following step-up sedation method was used: Step 1: Initial administration of an intravenous injection of midazolam (Nhwa Pharmaceutical Group Co. Ltd., Xuzhou, China; technical concentration of 5 g/L diluted to 0.25 g/L with normal saline) at 0.015 mg/kg (with a maximum dose of 1.0 mg). The Ramsay Sedation Scale score here was 1, and after a 3-5 min interval, a mouthpiece was placed in the patient’s mouth for the start of step 2. Step 2: Administration of 15-40 mg propofol (AstraZeneca, Shanghai, China; technical concentration of 10 g/L diluted to 5 g/L with normal saline) via intravenous injection until the Ramsay Sedation Scale score was 2-3. The endoscope then was passed through the patient’s throat. Step 3: Administration of an additional intravenous injection of propofol at 1.0 mg/kg per minute until the Ramsay Sedation Scale score was 5-6 (when retardation or loss of eyelash reflex was achieved)[16]. At this point, the endoscopic procedure was carried out.

For continuous sedation (groups Cc and Nc), the following technique was used: The patient was initially given an intravenous injection of midazolam at 0.015 mg/kg (with a maximum dose of 1.0 mg). Next, a mouthpiece was placed in the patient’s mouth, and he/she received an intravenous injection of propofol at 1.0 mg/kg per minute that did not stop until the Ramsay Sedation Scale score reached 5-6, when the endoscopic procedure was carried out. If necessary, propofol was administered again to prevent the patient from experiencing discomfort during long-lasting endoscopic procedures.

Patient age, sex, weight, alcohol and cigarette consumption, COPD and ASA classification, major endoscopic findings, SpO2, blood pressure, pulse rate, adverse events, dosage of midazolam and propofol, and recovery time were recorded. Recovery time was defined as the interval between the moment when propofol injection was stopped and when the patient could open his/her eyes in response to the doctor’s call and answer questions.

Monitoring

Degree of pharyngeal malaise during the endoscopic procedure: The same anesthetist and endoscopist, each with more than 5 years of experience, and a registered nurse who had worked for 10 years in an endoscopy room, independently evaluated the degree of pharyngeal malaise. Pharyngeal malaise was scored according to observations of the patient’s discomfort and the effect of passing the endoscope through the throat, as follows: obvious nausea and vomiting, difficulty continuing the endoscopic procedure (3 points); nausea and vomiting, able to continue the endoscopic procedure (2 points); slight nausea and vomiting, no effect on the endoscopic procedure (1 point); no nausea or vomiting, easy to finish the endoscopic procedure (0 points).

SpO2, blood pressure, and pulse rate: All patients were continuously monitored for SpO2, blood pressure, and pulse rate using a multi-functional monitor. The SpO2, blood pressure, and pulse rate were recorded before the procedure (1-2 min before the use of sedatives; this value, measured when the patient was resting on his/her side, was used as the base value), during the procedure (to identify the minimum value throughout the procedure), and after the procedure (1-2 min after the endoscopic procedure was completed). After the endoscopy, patients were continuously monitored in the recovery unit until mental ability and walking gait recovered to the normal level (usually within 30-60 min). Occurrences of adverse events were observed.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The measurement data were compared using the two-sample t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data. The enumeration data were expressed as n (%) and compared using the χ2 test. A two sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Degree of pharyngeal malaise during the endoscopic procedure

All endoscopies were completed successfully. Degrees of pharyngeal malaise evaluated by the anesthetist, endoscopist, and nurse did not differ significantly. The degree of pharyngeal malaise when the endoscope was passing through the throat in group Cs was greater than that in group Cc, and that in group Ns also was greater than group Nc (P < 0.05) (Table 2). However, the discomfort disappeared after the endoscope passed through the throat and propofol was administered again. All patients had no pharyngeal malaise and no memory of this discomfort after endoscopy.

Table 2.

Pharyngeal malaise when passing the endoscope through the throat n (%)

| Group | n |

Scores of degree of pharyngeal malaise |

|||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Cs | 43 | 33 (76.7)a | 7 (16.3) | 3 (7.0) | 0 |

| Cc | 43 | 40 (93.0) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| Ns | 41 | 31 (75.6)a | 6 (14.6) | 4 (9.8) | 0 |

| Nc | 41 | 38 (92.7) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) | 0 |

Group Cs: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with stepwise sedation; Group Cc: COPD with continuous sedation; Group Ns: Non-COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Nc: Non-COPD with continuous sedation.

P < 0.05 between Group Cs vs Group Cc and Group Ns vs Group Nc.

SpO2, blood pressure, and pulse rate

The average SpO2, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in all four groups decreased during the endoscopic procedure, but the blood pressure in almost all patients remained within the normal range. Only one patient in group Cc exhibited hypotension, but it was transient, did not require any treatment, and returned to normal rapidly after the endoscopic procedure. The pulse rate changed significantly during the procedure in group Cc and group Nc (Table 3).

Table 3.

SpO2, blood pressure, and pulse rate during the endoscopy procedure (mean ± SD)

| Group | Time | SpO2 (%) | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | P (bpm) |

| Cs | Before | 98.1 ± 1.6 | 126.0 ± 11.2 | 80.7 ± 6.7 | 74.4 ± 13.7 |

| (n = 43) | During | 95.8 ± 6.0b | 115.6 ± 11.9b | 72.8 ± 6.6b | 73.8 ± 14.0 |

| After | 98.0 ± 1.6 | 124.9 ± 11.3b | 79.1 ± 6.5b | 74.2 ± 14.1 | |

| Cc | Before | 98.0 ± 1.8 | 128.5 ± 11.0 | 80.5 ± 5.6 | 77.2 ± 14.3 |

| (n = 43) | During | 90.7 ± 13.6b | 113.5 ± 9.4b | 71.0 ± 4.9b | 75.0 ± 14.3b |

| After | 97.3 ± 2.6b | 126.3 ± 11.0b | 78.5 ± 5.8b | 76.6 ± 14.5 | |

| Ns | Before | 98.2 ± 1.8 | 130.2 ± 5.0 | 82.0 ± 4.1 | 73.7 ± 13.7 |

| (n = 41) | During | 96.5 ± 5.0a | 120.0 ± 5.2b | 74.3 ± 4.4b | 73.0 ± 13.7 |

| After | 98.1 ± 1.7 | 127.9 ± 5.0b | 80.0 ± 4.3b | 73.4 ± 13.6 | |

| Nc | Before | 98.2 ± 1.8 | 127.8 ± 9.3 | 81.4 ± 2.6 | 70.4 ± 12.7 |

| (n = 41) | During | 95.6 ± 6.7b | 117.1 ± 8.7b | 73.5 ± 2.9b | 69.0 ± 12.3b |

| After | 98.1 ± 1.7 | 125.5 ± 8.9b | 79.0 ± 2.7b | 70.4 ± 12.5 |

Group Cs: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with stepwise sedation; Group Cc: COPD with continuous sedation; Group Ns: Non-COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Nc: Non-COPD with continuous sedation; SpO2: Saturation of peripheral oxygen; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; P: Pulse rate.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs before the endoscopy.

Adverse events

Table 4 lists the adverse events in the four treatment groups. The overall rate of adverse events in group Cs was lower than that in group Cc (P < 0.01), but the difference between group Ns and group Nc was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Adverse events in the four treatment groups n (%)

| Adverse events |

Group |

|||

| Cs (n = 43) | Cc (n = 43) | Ns (n = 41) | Nc (n = 41) | |

| Hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90% for ≥ 15 s) | 4 (9.3)a | 12 (27.9) | 3 (7.3) | 5 (12.2) |

| SpO2 89%-80% | 2 (4.7) | 5 (11.2) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.3) |

| SpO2 79%-60% | 2 (4.7) | 5 (11.2) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) |

| SpO2 59%-40% | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| SpO2 < 40% | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Average decrease in value of SpO2 | 2.3 ± 5.4a | 7.3 ± 12.6 | 1.7 ± 4.3 | 2.6 ± 5.8 |

| Hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg or DBP < 60 mmHg) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Extent of SBP decrease | ||||

| ≤ 10 | 28 (65.1) | 17 (39.5) | 34 (82.9) | 28 (68.3) |

| 11-20 | 15 (34.9)a | 26 (60.5) | 7 (17.1) | 13 (31.7) |

| > 20 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Average decrease in value of SBP | 10.4 ± 3.3b | 15.1 ± 6.8 | 10.2 ± 3.3 | 10.6 ± 4.5 |

| Extent of DBP decrease | ||||

| ≤ 10 | 40 (93.0) | 34 (79.1) | 37 (90.2) | 38 (92.7) |

| 11-20 | 3 (7.0) | 9 (20.9) | 4 (9.8) | 3 (7.3) |

| > 20 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Average decrease in value of DBP | 7.9 ± 2.2b | 9.5 ± 1.8 | 7.6 ± 2.6 | 8.0 ± 1.7 |

| Tachycardia (> 100 bpm) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) |

| Bradycardia (< 60 bpm) | 3 (7.0) | 6 (14.0) | 3 (7.3) | 4 (9.8) |

| Decrease of pulse rate | 33 (76.7) | 36 (83.7) | 29 (70.7) | 28 (68.3) |

| Increase of pulse rate | 8 (18.6) | 6 (14.0) | 8 (19.5) | 8 (19.5) |

| No change of pulse rate | 2 (4.7) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (9.8) | 5 (12.2) |

| Average change in value of pulse rate | 0.6 ± 2.8a | 2.2 ± 2.8 | 0.7 ± 2.4 | 1.4 ± 2.5 |

| Arrhythmias | 2 (4.7) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other adverse events | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.6) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.3) |

| Extrapyramidal reactions | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Somnolence | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| Dizziness | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) |

| Overall rate of adverse events | 15 (34.9)b | 27 (62.8) | 11 (26.8) | 13 (31.7) |

Group Cs: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with stepwise sedation; Group Cc: COPD with continuous sedation; Group Ns: Non-COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Nc: Non-COPD with continuous sedation; SpO2: Saturation of peripheral oxygen; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure. Overall rate of adverse events included hypoxemia, hypotension, tachycardia, bradycardia, arrhythmias and other adverse events.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs Group Cc.

Hypoxemia

Twenty-four patients (14.3%) in all four groups exhibited hypoxemia. The occurrence of hypoxemia in group Cs was significantly lower than that in group Cc (9.3% and 27.9%, respectively, P < 0.05). The average decrease in value of SpO2 during the procedure in group Cs was significantly lower than that in group Cc (P < 0.05). For 22 patients with slight hypoxemia (SpO2 ≥ 60%), SpO2 quickly returned to normal after holding the mandible with two hands, patting him/her on the back, and increasing oxygen flow through the nasal catheter. For these patients, the endoscopic procedure was continued and completed. For two patients with serious hypoxemia (SpO2 < 60%), SpO2 returned to normal after removing the endoscope, holding the mandible with two hands, pressing the chest, sucking out sputum, giving oxygen by mask, and intravenously injecting the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (0.5 mg). The endoscopic procedure in these patients was restarted and completed after awakening, and with no obvious signs of discomfort during the endoscopic procedure.

Hypotension

Only one patient in group Cc had hypotension (88/60 mmHg). The average decreases in values of SBP and DBP in group Cs were significantly lower than those in group Cc (P < 0.001 for SBP and P < 0.005 for DBP).

Change of pulse rates

The pulse rates of patients in the four groups showed a slight increase (1-6 bpm), no change, or a slight decrease (1-7 bpm) during the procedure. The average change in value of pulse rate in group Cs was lower than that in group Cc (P < 0.05).

Other adverse events

During the injection with propofol, one patient in group Cc exhibited extrapyramidal signs (abnormal involuntary movement of limbs and opisthotonus), which disappeared after 30-60 s. Incidence of somnolence and dizziness did not differ significantly among the four groups, and disappeared within 10-50 min after the endoscopic procedure ended.

Dosage of midazolam and propofol

Midazolam dosages in groups Cs, Cc, Ns and Nc were 0.6-1.0 mg (0.90 ± 0.12 mg, 0.90 ± 0.11 mg, 0.90 ± 0.11 mg, and 0.92 ± 0.10 mg, respectively), and differences in dosages were not statistically significant among the four groups. Propofol dosages in groups Cs, Cc, Ns and Nc were 53.3 ± 9.4 mg (30-80 mg), 58.9 ± 11.6 mg (40-80 mg), 64.8 ± 10.1 mg (40-80 mg), and 70.7 ± 9.6 mg (50 -88 mg), respectively. Propofol dosage in group Cs was significantly lower than that in group Cc (P < 0.05), and dosage in group Ns also was significantly lower than group Nc (P < 0.01).

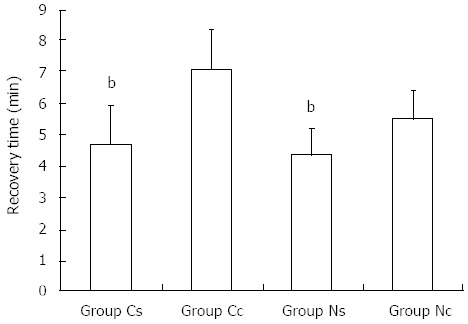

Recovery time

The recovery times in groups Cs, Cc, Ns and Nc were 4.7 ± 1.2 min (2.5-8.0 min), 7.1 ± 1.2 min (3.5-10.0 min), 4.4 ± 0.8 min (2.5-6.0 min), and 5.5 ± 0.9 min (3.0-7.0 min), respectively. The recovery time in group Cs was significantly shorter than that in group Cc, and that in group Ns also was significantly shorter than group Nc (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). All patients were fully conscious and able to answer questions accurately within 10 min after endoscopy. They were able to walk normally when they left the endoscopic unit 30-60 min after endoscopy. The majority of patients reported no discomfort; only 12 patients had slight dizziness and somnolence, which disappeared within 10-50 min after the endoscopic procedure ended.

Figure 2.

Recovery times of patients in the four groups. Group Cs: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with stepwise sedation; Group Cc: COPD with continuous sedation; Group Ns: Non-COPD with stepwise sedation; Group Nc: Non-COPD with continuous sedation. bP < 0.01 between Group Cs vs Group Cc and Group Ns vs Group Nc.

DISCUSSION

Both the number and complexity of endoscopic procedures have increased considerably due to the wide availability and application of sedation, but the best methods for sedation during endoscopy are still being debated[17]. Providing an adequate regimen of sedation is an art, as it influences the quality of the examination and patient and physician satisfaction with the sedation process[18]. Conscious sedation, a type of sedation in which the individual can respond to verbal directions, is used for GI endoscopy. Even with this sedation, patients can experience discomforts such as nausea and vomiting, which in some cases precludes completing the endoscopic procedure. Deep sedation may be preferred for procedures in which it is important for patients to remain immobile[19]. However, selection of the most suitable drug or combination of drugs for use and the safety of the sedation method for special patient groups, such as elderly individuals and patients with co-morbidities, are important issues that need to be resolved[11,20-22].

Martínez et al[23] reported that continuous propofol sedation during endoscopic procedures is as safe in elderly patients > 80 years as it is in younger patients. Our results also showed that differences in hypoxemia, hypotension, and all adverse events in non-COPD patients with continuous sedation were not statistically different from those in non-COPD patients with stepwise sedation. We have used continuous propofol combined with midazolam for deep sedation during upper GI endoscopy since 1999[24], but sedation for patients with respiratory diseases accompanied by cough, phlegm, and snoring has been limited, as these patients are prone to experience respiratory track blockage by phlegm and lingual root fall back under sedation, resulting in decreased SpO2 and respiratory inhibition. Most episodes of hypoxemia during sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy occur within 5 min of the administration of medication and/or intubation, and less frequent administration of medications or diligent monitoring during this period might decrease hypoxemia[14]. For this class of patients, we proposed using a new sedation method that would allow patients to gradually reach the appropriate sedation depth via administration of propofol combined with midazolam in three stages. When the Ramsay Sedation scale was 2-3, the endoscope was passed through the patient’s throat. At this moment, the patients were conscious, and the procedure usually did not lead to cough reflex disappearance, lingual root fall back, or respiratory track blockage by phlegm. Therefore, this method reduced the decline of SpO2 during the endoscopy.

In this study, the patients who underwent the stepwise sedation method also exhibited a smaller decrease in SBP, DBP, and pulse rate than patients who received continuous sedation. The new method, moreover, reduced the propofol dosage and the overall rate of adverse events. Elderly patients with COPD have much greater risk of experiencing cardiopulmonary abnormality during upper GI endoscopic procedures than elderly patients without COPD, thus use of the stepwise sedation method is safer for these patients. This method will contribute to the wider use of upper GI endoscopy in diagnosis and treatment of alimentary system diseases.

Midazolam and propofol are commonly used in sedative endoscopic procedures at doses of 0.05-0.1 mg/kg and 1-3 mg/kg, respectively. In our study, propofol combined with midazolam was used, and the midazolam dosage was decreased to less than 0.015 mg/kg (the range was 0.6-1.0 mg). Moreover, the required propofol dosage in the stepwise sedation was significantly lower than that in the continuous sedation (53.3 ± 9.4 mg and 58.9 ± 11.6 mg, respectively, for elderly patients with COPD). In addition, the concentration of midazolam was diluted 20 times and that of propofol was diluted two times, which resulted in reduced drug dosage, consistent with previous reports[25]. Drug dosage (which allows for control of degree of sedation) is one of the key factors for a successful upper GI endoscopy procedure. Generally, drug dosage is proportional to its adverse effects. In our study, the dosage of sedative was lower and the incidence of hypoxemia and the extent of decreased blood pressure were lower than those reported in the literature[26]. The overall rate of adverse events when the stepwise sedation was used for elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD was significantly lower than that when the continuous sedation was used. The recovery time also was shorter for the stepwise sedation than the continuous sedation. There was no mortality in our study. Agostoni et al[27] reported that the endoscopic procedure resulted in 3 deaths in a total of 17999 patients (mortality rate = 0.017%).

In conclusion, the findings of this study showed that the stepwise sedation method reduced the propofol dosage and the extent of the drop in SpO2 and blood pressure, and also decreased the incidence of hypoxemia and the overall rate of adverse events. Thus, this method was shown to be safer than the continuous sedation method in elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD during upper GI endoscopy.

COMMENTS

Background

The incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Chinese urban populations over 40 years old is 8.2%. Many patients with COPD have to undergo upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy because of digestive symptoms. However, elderly patients with COPD usually have cough, phlegm, and respiratory insufficiency, and are more likely to experience decreased saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) because of dysfunction of the cough reflex and respiratory track blockage by phlegm during an endoscopic procedure with sedation. This oftentimes leads to a higher risk of adverse events during routine GI endoscopy in these patients. Therefore, a sedation method specially designed for elderly patients with COPD is urgently needed for use in clinical practice.

Research frontiers

In recent years endoscopy with sedation has become a popular option for both patients and gastroenterologists. Midazolam and propofol are generally used as sedatives during endoscopic procedures. However, propofol is a potent depressant of airway reflexes at hypnotic concentrations. It is critical to properly determine how to improve the safety of GI endoscopy by lowering the doses of sedatives.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Due to inadequate experience with the application of sedation technology during endoscopy in past decades, patients typically underwent routine endoscopic procedures without sedatives. This methodology can lead to various adverse effects, including fear, nausea and vomiting, elevated blood pressure, angina, myocardial infarction, and even death. These issues give rise to patient reluctance to be examined and delay of diagnosis and treatment of alimentary system diseases. We took the lead in using sedatives during endoscopic procedures in China in 1998. In the current study, we designed a new stepwise sedation method that involves three-stage administration of propofol combined with midazolam so that sedation depth is approached gradually. The results indicate that the stepwise sedation method is effective and safer than the continuous sedation method for elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD during upper GI endoscopy.

Applications

This stepwise sedation method can reduce drug dosage and the overall rate of adverse events in elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD during upper GI endoscopy with sedation. This will contribute to the wider use of upper GI endoscopy in diagnosis and treatment of alimentary system diseases.

Peer review

This is an interesting study and deserves attention, as the results are relevant to specific patients with COPD who need to undergo endoscopy examination. This manuscript presents new concepts and ideas. The authors analyzed the efficacy and safety of stepwise sedation for elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD during GI endoscopy. The results suggest that stepwise sedation is an effective and safe sedation method that can be used for elderly patients with mild/moderate COPD.

Footnotes

Supported by A Grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81172301

P- Reviewers Andrejic BM, Chiu CT S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, Chen P, Kang J, Huang S, Chen B, Wang C, Ni D, Zhou Y, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:753–760. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1749OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin HH, Murray M, Cohen T, Colijn C, Ezzati M. Effects of smoking and solid-fuel use on COPD, lung cancer, and tuberculosis in China: a time-based, multiple risk factor, modelling study. Lancet. 2008;372:1473–1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61345-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavic SM, Basson MD. Complications of endoscopy. Am J Surg. 2001;181:319–332. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romagnuolo J, Cotton PB, Eisen G, Vargo J, Petersen BT. Identifying and reporting risk factors for adverse events in endoscopy. Part I: cardiopulmonary events. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romagnuolo J, Cotton PB, Eisen G, Vargo J, Petersen BT. Identifying and reporting risk factors for adverse events in endoscopy. Part II: noncardiopulmonary events. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:586–597. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jałocha L, Wojtuń S, Gil J. [Incidence and prevention methods of complications of gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures] Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2007;22:495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitzky BE, Lopez R, Dumot JA, Vargo JJ. Moderate sedation for elective upper endoscopy with balanced propofol versus fentanyl and midazolam alone: a randomized clinical trial. Endoscopy. 2012;44:13–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulos JE, Kalogerinis PT, Caudle JN. Propofol compared with combination propofol or midazolam/fentanyl for endoscopy in a community setting. AANA J. 2013;81:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correia LM, Bonilha DQ, Gomes GF, Brito JR, Nakao FS, Lenz L, Rohr MR, Ferrari AP, Libera ED. Sedation during upper GI endoscopy in cirrhotic outpatients: a randomized, controlled trial comparing propofol and fentanyl with midazolam and fentanyl. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:45–51, 51.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Beek EJ, Leroy PL. Safe and effective procedural sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:171–185. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31823a2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerker A, Hardt C, Schlief HE, Dumoulin FL. Combined sedation with midazolam/propofol for gastrointestinal endoscopy in elderly patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heuss LT, Schnieper P, Drewe J, Pflimlin E, Beglinger C. Conscious sedation with propofol in elderly patients: a prospective evaluation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1493–1501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundman E, Witt H, Sandin R, Kuylenstierna R, Bodén K, Ekberg O, Eriksson LI. Pharyngeal function and airway protection during subhypnotic concentrations of propofol, isoflurane, and sevoflurane: volunteers examined by pharyngeal videoradiography and simultaneous manometry. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1125–1132. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200111000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qadeer MA, Lopez AR, Dumot JA, Vargo JJ. Hypoxemia during moderate sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy: causes and associations. Digestion. 2011;84:37–45. doi: 10.1159/000321621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.COPD Group of Chinese Society of Respiratory Diseases. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2007;46:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974;2:656–659. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5920.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Triantafillidis JK, Merikas E, Nikolakis D, Papalois AE. Sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy: current issues. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:463–481. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell GD. Preparation, premedication, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2004;36:23–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nayar DS, Guthrie WG, Goodman A, Lee Y, Feuerman M, Scheinberg L, Gress FG. Comparison of propofol deep sedation versus moderate sedation during endosonography. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2537–2544. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Hidaka N, Ichise Y, Kajiyama M, Tanaka N. Low-dose propofol sedation for diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy: results in 10,662 adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1650–1655. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Tanaka N, Ichise Y, Katsuyama Y, Ohmori S. Propofol sedation for endoscopic procedures in patients 90 years of age and older. Digestion. 2008;78:20–23. doi: 10.1159/000151765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klotz U. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41:67–76. doi: 10.1080/03602530902722679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martínez JF, Aparicio JR, Compañy L, Ruiz F, Gómez-Escolar L, Mozas I, Casellas JA. Safety of continuous propofol sedation for endoscopic procedures in elderly patients. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:76–82. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Can-Xia Xu, Wu-Liang Tang, Xi-Wuang Jiang, Ding-Hua Xiao. Effect of combined sedation with midazolam and propofol for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2000;8:1197–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amornyotin S, Srikureja W, Chalayonnavin W, Kongphlay S. Dose requirement and complications of diluted and undiluted propofol for deep sedation in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenstein DR, Jagannath S, Baron TH, Anderson MA, Banerjee S, Dominitz JA, Fanelli RD, Gan SI, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO, et al. Sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agostoni M, Fanti L, Gemma M, Pasculli N, Beretta L, Testoni PA. Adverse events during monitored anesthesia care for GI endoscopy: an 8-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]