Abstract

AIM: To compare outcome of stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) vs LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy (LH) by a meta-analysis of available randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

METHODS: Databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and the Science Citation Index updated to December 2012, were searched. The main outcomes measured were operating time, early postoperative pain, postoperative urinary retention and bleeding, wound problems, gas or fecal incontinence, anal stenosis, length of hospital stay, residual skin tags, prolapse, and recurrence. The meta-analysis was performed using the free software Review Manager. Differences observed between the two groups were expressed as the odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI. A fixed-effects model was used to pool data when statistical heterogeneity was not present. If statistical heterogeneity was present (P < 0.05), a random-effects model was used.

RESULTS: The initial search identified 10 publications. After screening, five RCTs published as full articles were included in this meta-analysis. Among the five studies, all described a comparison of the patient baseline characteristics and showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Although most of the analyzed outcomes were similar between the two operative techniques, the operating time for SH was significantly longer than for LH (P < 0.00001; OR= -6.39, 95%CI: -7.68 - -5.10). The incidence of residual skin tags and prolapse was significantly lower in the LH group than in the SH group [2/111 (1.8%) vs 16/105 (15.2%); P = 0.0004; OR= 0.17, 95%CI: 0.06-0.45). The incidence of recurrence after the procedures was significantly lower in the LH group than in the SH group [2/173 (1.2%) vs 13/174 (7.5%); P = 0.003; OR= 0.21, 95%CI: 0.07-0.59].

CONCLUSION: Both SH and LH are probably equally valuable techniques in modern hemorrhoid surgery. However, LigaSure might have slightly favorable immediate postoperative results and technical advantages.

Keywords: Stapled hemorrhoidopexy, Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy, Hemorrhoids, Meta-analysis

Core tip: Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) and Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy are probably equally valuable techniques in modern hemorrhoid surgery. However, appropriate surgical techniques are important in SH, especially the placement of the purse-string suture. Its misplacement may cause operative and postoperative complications.

INTRODUCTION

Around 5% of the general population has hemorrhoidal disease to some extent, especially those aged > 40 years[1,2]. There is a vast number of available therapeutic methods, and hemorrhoidectomy is well established as the most effective and definitive treatment for grades 3 and 4 symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease[3]. Two well-established methods of hemorrhoidectomy, the open (Milligan-Morgan)[4] and closed (Ferguson)[5] techniques are especially popular. However, despite the relatively minor surgical trauma of these two methods, the intraoperative pain and protracted postoperative course are major concerns[6]. Thus, continuing efforts have been made to develop new techniques and modifications that promise a less painful course and faster recovery. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy [SH, also known as procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH)] was introduced by Longo in 1998, and uses a specially designed circular stapling instrument to excise a ring of redundant rectal mucosa or expanded internal hemorrhoids[7]. Although some SH-related complications have been reported[8], its advantages, such as shorter operating time, less postoperative pain, and a quicker return to normal activity have been confirmed by several controlled studies[9-11]. Another new method, LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy (LH), uses the Ligasure vessel sealing system, which consists of a bipolar electrothermal hemostatic device that allows complete coagulation of vessels up to 7 mm in diameter with minimal surrounding thermal spread and limited tissue charring. The advantages of this method include simple and easy learning, excellent hemostatic control, minimal tissue trauma, lower postoperative pain, and shorter wound healing time[12-14].

Although meta-analysis of clinical trials has shown that SH and LH have some advantages over conventional hemorrhoidectomy[15], there is still a lack of evidence about the operative and postoperative outcomes of SH and LH. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficiency of SH and LH in treating hemorrhoidal disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

Electronic databases, including PubMed (1966 to December 2012), EMBASE (1980 to December 2012), the Cochrane library (Issue 12, December 2012) and Science Citation Index (1975 to December 2012), were searched. Literature reference lists were hand-searched for the same time period. The search terms used were “Stapled hemorrhoidopexy or PPH and LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy”.

Study selection

The initial inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) all originally published RCTs; (2) the treatment group underwent SH for hemorrhoidal disease; and (3) a parallel control group underwent LH for hemorrhoidal disease. Studies that met the initial inclusion criteria were then further examined. Those with duplicate publications, unbalanced matching procedures or incomplete data were excluded, in addition to abstracts without accompanying full texts.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (Yang J and Cui PJ) according to the prescribed selection criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. The following data were extracted: baseline trial data (e.g., sample size, mean age, gender, study protocol, grade of hemorrhoids, and follow-up time); operative and postoperative outcomes (operating time, early postoperative pain, postoperative urinary retention and bleeding, wound problems, gas or fecal incontinence, anal stenosis, length of hospital stay, residual skin tags, prolapse, and recurrence). When necessary, the corresponding authors were contacted to obtain supplementary information.

Study quality

The quality of the included trials was assessed using the Jadad composite scale[16] in addition to a description of an adequate method for allocation concealment[17]. Study quality was assessed independently by two authors (Yang J and Cui PJ), and any discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by consensus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality analysis of included trials

| Ref. | Randomization method | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Withdraws | Jadad score |

| Arslani et al[1] | Not mentioned | Adequate | No | Described | 4 |

| Basdanis et al[18] | Not mentioned | Adequate | No | Not mentioned | 3 |

| Chen et al[19] | Not mentioned | Adequate | No | Not mentioned | 3 |

| Kraemer et al[20] | Computer-generated | Adequate | No | Described | 5 |

| Sakr et al[21] | Computer-generated | Adequate | Single-blind | Described | 5 |

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using the free software Review Manager (Version 4.2.10, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). Differences observed between the two groups were expressed as the OR with the 95%CI. A fixed-effects model was used to pool data when statistical heterogeneity was not present. If statistical heterogeneity was present (P < 0.05), a random-effects model was used.

RESULTS

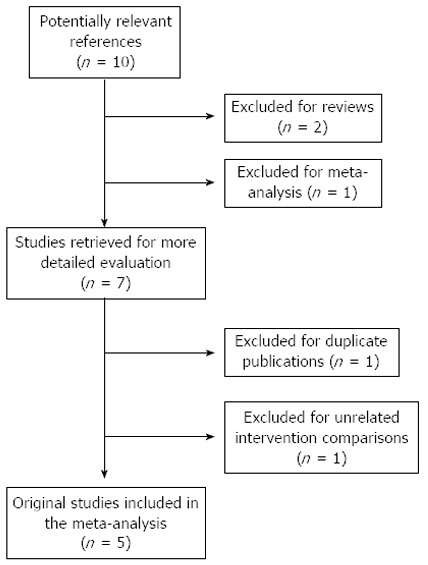

The initial search identified 10 publications (Figure 1). After screening, seven RCTs were identified. Consequently, two trials were excluded from the pooled meta-analysis. We compared the conventional Ferguson technique with SH and LH and the other study was a duplicate publication. Five RCTs[1,18-21] published as full articles were included in this meta-analysis. All five studies described a comparison of the patient baseline characteristics and showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. The principal characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The outcomes were measured as follows.

Figure 1.

Search protocol for the meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of included trials in the meta-analysis

| Ref. | Year | Technique (n) | Study protocol | Mean age (yr) | Sex (M/F) | Grade of hemorrhoids | Follow-up time (mo) |

| Arslani et al[1] | 2012 | SH (46) | RUT | 52 (17-72) | 21/25 | 3 | 24 |

| LH (52) | 50 (18-78) | 23/29 | |||||

| Basdanis et al[18] | 2005 | SH (50) | RUT | 46 (25–72) | 29/21 | 3 and 4 | 6-clinical, 18 (12–24)- telephone |

| LH (45) | 44 (22–69) | 25/20 | |||||

| Chen et al[19] | 2007 | SH (44) | RUT | 25-81 (48) | 26/18 | 3 | 6 |

| LH (42) | 23-85 (46) | 24/18 | |||||

| Kraemer et al[20] | 2005 | SH (25) | RUT | 58 (40–71) | 14/11 | 3 and 4 | 1.5 |

| LH (25) | 48 (28–82) | 13/12 | |||||

| Sakr et al[21] | 2010 | SH (34) | RBT | 43.7 ± 4.66 (29–56) | 21/13 | 3 and 4 | 18 |

| LH (34) | 39.3 ± 4.68 (33–52) | 19/15 |

RUT: Randomized unblinded trial; RBT: Randomized blinded trial; SH: Stapled hemorrhoidopexy; LH: LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy.

Table 3.

Characteristics of randomized comparisons of stapled hemorrhoidopexy and LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy reported in the literature

| Ref. | Technique | Operation time (min) | Hospitalization (d) | Postoperative pain (Visual Analog score) | Parenteral analgesic use | Postoperative urinary retention | Postoperative bleeding | Return to normal activity or work | Incontinence for gas or stool after the operation | Postoperative anal stenosis | Residual skin tags and prolapse | Wound Problems | Recurrence |

| Arslani et al[1] | SH | NR | NR | 3 (1-5) | 36 | 1 | 3 | 3-4 wk | 2 | 2 | 6 | NR | 5 |

| LH | 3 (1-6) | 41 | 2 | 1 | 2-4 wk | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Basdanis et al[18] | SH | 15 (8-17) | 4 (2-10) | 3 (1-6) | 1 | 7 | 0 | NR | 1 | NR | NR | 6 | 3 |

| LH | 13 (9.2-16.1) | 5 (2-10) | 6 (3-7) | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 39 | 0 | ||||

| Chen et al[19] | SH | 19.0 ± 6.4 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 23 | NR | 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4 | 1 |

| LH | 12.0 ± 4.1 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 2.4 | 35 | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||||||

| Kraemer et al[20] | SH | 21 (6-54) | 1.6 (1-2) | Only showed the trend | 3.8 (2-12) | 4 | 3 | 6.3 (1.5) d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | NR |

| LH | 26 (10-80) | 2.1 (2-3) | Only showed the trend | 3.2 (1-8) | 2 | 1 | 9.8 (1.9) d | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Sakr et al[21] | SH | 26.9 ± 3.26 | 2.44 ± 0.504 | 5.29 ± 0.914 | 5.7 ± 0.855 | 1 | 2 | 8.65 ± 0.485 d | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| LH | 20.8 ± 3.35 | 2.21 ± 0.410 | 5.53 ± 1.02 | 5.0 ± 0.776 | 2 | 1 | 7.68 ± 0.638 d | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

NR: Not reported; LH: LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy SH: Stapled hemorrhoidopexy.

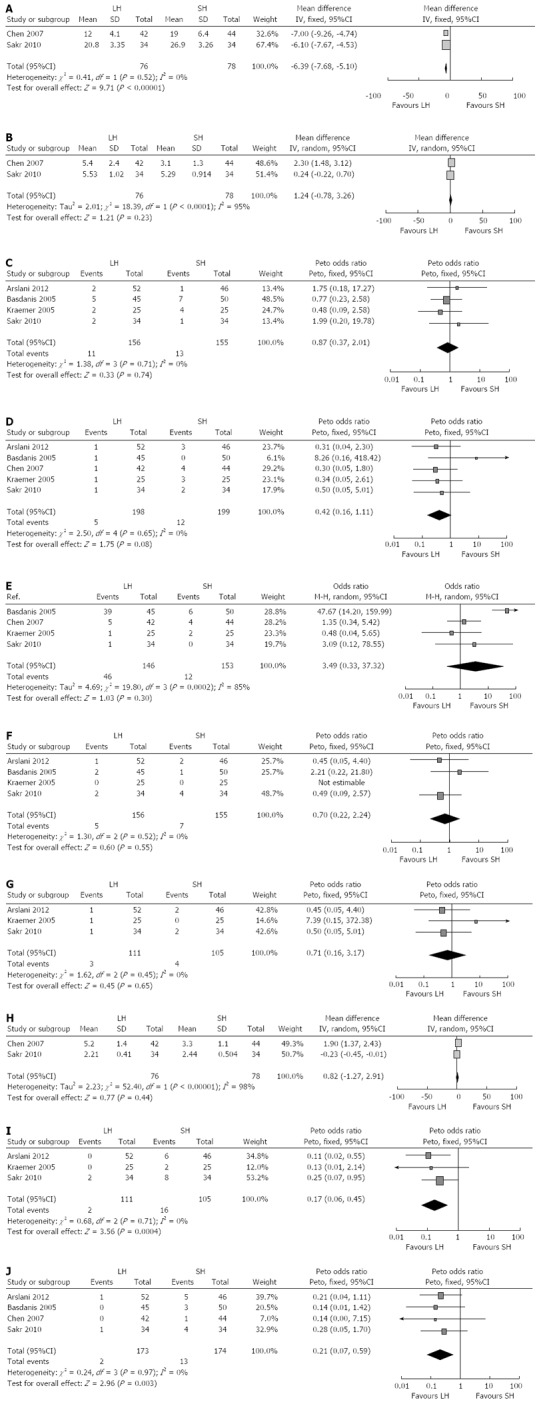

Operating time

Four trials reported the operating time during hemorrhoidectomy[18-21]. However, two of them only reported the average operating time[18,20]. The combined data showed that the operating time of SH was significantly longer than that of LH (P < 0.00001; OR = -6.39, 95%CI: -7.68 - -5.10) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Comparison of outcome between LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy and stapled hemorrhoidopexy. A: Operating time; B: Early postoperative pain; C: Postoperative urinary; D: Postoperative bleeding; E: Wound problems; F: Postoperative gas or fecal incontinence; G: Postoperative anal stenosis; H: Hospitalization; I: Residual skin tags and prolapse; J: Recurrence. LH: LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy SH: Stapled hemorrhoidopexy.

Early postoperative pain

All five trials reported early postoperative pain at varied time points after hemorrhoidectomy[1,18-21] with a Visual Analog scale (VAS) score (0 indicating no pain and 10 severe pain). Two trials reported average VAS scores[1,18] and only one showed the trend in postoperative VAS scores[20]. Combined data from the other two trials showed that there was no difference between LH and SH (P = 0.23; OR = 1.24, 95%CI: -0.78 - -3.26) (Figure 2B).

Postoperative urinary retention

Four trials reported urinary retention[1,18,20,21] after the procedure and there was no significant difference between the LH and SH groups [11/156 (7.1%) vs 13/155 (8.4%); P = 0.74; OR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.37-2.01) (Figure 2C).

Postoperative bleeding

All five trials reported postoperative bleeding[1,18-21]. There was no significant difference between the LH and SH groups [5/198 (2.5%) vs 12/199 (6%); P = 0.08; OR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.16-1.11) (Figure 2D).

Wound problems

Four trials reported procedure-related wound problems, including irritation, itching and moisture[18-21]. There was no significant difference between the LH and SH groups [46/146 (31.5%) vs 12/153 (7.8%); P = 0.3; OR = 3.49, 95%CI: 0.33-37.32) (Figure 2E).

Postoperative gas or fecal incontinence

Four trials reported the incidence of postoperative gas or fecal incontinence[1,18,20,21]. There was no significant difference between the LH and SH groups [5/156 (3.2%) vs 7/155 (4.5%); P = 0.55; OR = 0.70, 95%CI: 0.22-2.24] (Figure 2F).

Postoperative anal stenosis

Three trials reported postoperative anal stenosis[1,20,21]. There was no significant difference between the LH and SH groups [3/111 (2.7%) vs 4/105 (3.8%); P = 0.65; OR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.16-3.17] (Figure 2G).

Hospitalization

Four trials reported the length of hospital stay after hemorrhoidectomy[18-21]. However, two of them only reported the average time[18,20]. Combined data from the other two trials showed that there was no difference between LH and SH (P = 0.44; OR = 0.82, 95%CI: -1.27-2.91) (Figure 2H).

Residual skin tags and prolapse

Three trials reported residual skin tags and prolapse[1,20,21]. The data showed that the incidence of residual skin tags and prolapse was significantly lower in the LH group than in the SH group [2/111 (1.8%) vs 16/105 (15.2%); P = 0.0004; OR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.06-0.45] (Figure 2I).

Recurrence

Four trials reported the incidence of recurrence after the procedures[1,18,19,21]. The data showed that the incidence of recurrence was significantly lower in the LH group than in the SH group [2/173 (1.2%) vs 13/174 (7.5%); P = 0.003; OR = 0.21, 95%CI: 0.07-0.59] (Figure 2J).

DISCUSSION

Hemorrhoid is one of the most common anorectal disorders[2]. Although accepted as the gold standard for surgical treatment of hemorrhoids, conventional hemorrhoidectomy has some unavoidable drawbacks. Two recent techniques, SH and LH, provide some advantages over conventional hemorrhoidectomy. However, there is still a lack of evidence focusing on outcomes of SH and LH.

Our meta-analysis showed that LH took significantly less time to complete compared with SH. For SH, a special anal dilator was used to set an interrupted purse-string suture above the dentate line. Then the suture was tightened around the anvil of the circular stapler. In some patients with significant prolapse of the anal mucosa, two circular interrupted sutures were used. After removal of the stapler, interrupted stitches were usually inserted to control bleeding points. With regard to LH, the procedure was more convenient. The LigaSure instrument was used to grasp the base of the hemorrhoid and activated. After coagulation, the hemorrhoid skin was excised with scissors. The reduced operating time was related to better hemostatic control and lack of any need to ligate the pedicles. Our meta-analysis was in accordance with the results of a study showing that LH was comparatively simple and easy to learn[20]. However, the median value and standard deviation (SD) were reported only in two studies, so this variable should be investigated in further studies.

Another significant difference between the SH and LH groups in our meta-analysis was a higher frequency of postoperative residual skin tags, prolapse and recurrence with SH. This might have been because SH does not excise the hemorrhoids but rather a circumferential column of mucosa and submucosa 2-3 cm above the dentate line and then staples the defect. Besides, it does not deal with external hemorrhoids or associated anal canal problems[22-24]. However, patients with the third or fourth degree hemorrhoids usually present with large unequally sized prolapsing piles or circumferential hemorrhoids. Chen et al[25] proposed one modified method with one to four additional traction sutures placed at sites about 1 cm below the level of the purse-string suture for those prominent hemorrhoidal positions. This helped to incorporate more distal components of internal hemorrhoids into the “stapler housing” and facilitated further resection. It was also able to pull the external components or skin tags into the anal canal and made the anal surface smoother. An alternative is to remove the residual prolapsing hemorrhoidal tissue or skin tags during the operation or at the postoperative stage.

Long-term risk of recurrence, which is usually defined as recurring symptoms or new prolapse (but not residual prolapse or skin tags)[1], is the main concern of patients and surgeons. Some studies found that the residual prolapsed piles could cause recurrent symptoms[26,27], so it is understandable that recurrence was higher in the SH group. Our meta-analysis was in accordance with the findings of several studies that reported a high recurrence rate of 10%-53%[11,28,29]. SH is therefore considered by some authors to be unsuitable for grade 4 hemorrhoids[22,29]. On the contrary, LH is more appropriate for treating anatomical deformities such as skin tags and prolapse. Using LH, concomitant external hemorrhoid components and skin tags can be addressed, ensuring complete removal of the hemorrhoid tissues[30]. When severe external piles are dominant or large skin tags accompany hemorrhoid prolapse, LH will be a good choice[12-14]. Considering that the surgical principle in LH is more similar to that of conventional hemorrhoidectomy, it would be expected that LH would have lower recurrence rates[30]. However, the follow-up time did not exceed two years in our included trials, therefore, further studies with longer follow-up are needed.

One study showed that SH caused severe postoperative pain[31]. However, the results were challenged by several other studies[26,32,33]. To the best of our knowledge, the rectal wall is innervated by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, thus, excising the rectal mucosa should be painless. So, it is inexplicable why pain is a common immediate complication of SH. Pain is usually caused by anal dilatation, which leads to internal sphincter fragmentation in some patients[34], and the inclusion of smooth muscle in the doughnut[31]. It is conceivable that SH is more technically demanding and operator dependent. If the purse-string suture is not at an inadequate level or depth, serious postoperative pain may be avoided[28]. VAS scores in the SH group were always lower in patients with no fibers included in the excised piles and doughnuts[18]. Considering the surgical similarity between LH and conventional hemorrhoidectomy, it would be expected that patients receiving LH would present with greater postoperative pain compared with SH, as is found with conventional hemorrhoidectomy. However in our meta-analysis, there was no difference between LH and SH regarding average VAS scores. The low level of postoperative pain with LH may result from the fact that LH has no need for anal dilatation, which reduces the possibility of anal spasm[35] and temporary third degree burn injury to nerve endings at the site of the wound[36]. However, there were some limitations to our data. The median value and SD were only reported in two studies, and oral and parenteral analgesia requirements were reported too inconsistently for quantitative analysis.

In our meta-analysis the occurrence of postoperative bleeding was equivalent in the two groups. LigaSure is a diathermy system and allows complete coagulation of blood vessels up to 7 mm in diameter, using a precise amount of bipolar energy and pressure that permanently changes collagen and elastin within the vessel wall. However, for SH, the expected frequency of bleeding was at least 50%[37]. In some circumstances, too much folded mucosa in the stapled line will increase the occurrence of inefficient hemostasis[38]. Therefore, interrupted stitches were needed to control bleeding points after removal of the stapler in almost all patients.

Early postoperative partial incontinence may be explained by pain that hinders voluntary sphincter contraction[39]. However potential anal sphincter injury may cause impairment of fecal continence. During SH, intraoperative sphincter stretching may play a role in postoperative fecal incontinence. The procedure requires insertion of a relatively large anal dilator, usually 33 mm, and placement of the circular stapler can lead to further sphincter injury[37], especially when excessive mucosal prolapse hampers the instrument encompassing all of the redundant tissue. Thus, in patients with pre-existing sphincter injury or with a narrow anal canal, modified techniques introduced by Ho et al[40] may minimize the risk of stretching the internal anal sphincter. They used the smaller Eisenheimer anal retractor instead of the circular anal dilator. Furthermore, if the deeper layers of the rectal wall are not included into the purse-string, making a mucosal instead of an all wall rectal layer anastomosis may reduced the incidence of SH-related postoperative incontinence and stenosis[38].Theoretically, intraoperative sphincter stretching was minimized when using the LigaSure system[41]. The system also had an effect on preservation of internal sphincter pressure[42]. However, in our meta-analysis, five cases of temporary gas incontinence and three of anal stenosis were encountered after LH, and one patient remained incontinent to gas for 1 mo[18]. Ramcharan et al[35] reported that after LH, the perianal skin, including the skin bridges, appeared scalded. At 3 mo follow-up, there was some mild circumferential fibrosis in the skin of the anal margin, which produced symptomatic anal stenosis that required once daily anal dilation with a 12-15-mm dilator for 3 mo. Therefore, occurrence of incontinence and stenosis with LH may be related to the device and technique. The LigaSure clamp may grasp the internal anal sphincter as well as the hemorrhoidal tissue above it. Thermal energy causes scalding that can contribute to anal stenosis. Similar mechanisms may result in injury to the anal sphincter, which may account for the fecal incontinence. To avoid this phenomenon, it is important: (1) to cut the anorectal margin with the cold knife before hemorrhoidectomy; (2) on the mucosal margin rather than on the cutaneous margin; and (3) to retract the cutaneous margin from bipolar blades before the sealing cycle begins[30,43]. When stenosis occurs, an early conservative approach with dilators will successfully treat this condition[43].

The prolonged hospital stays and delayed recovery usually related to the postoperative pain and wound problems. Our previous data showed that SH and LH have an equal effect in reducing postoperative pain. Although Basdanis et al[18] reported high occurrence of pruritus with LH immediately after the operation, our meta-analysis showed that wound problems did not differ significantly between the LH and SH groups. Therefore, as a consequence of reduced postoperative pain and tissue injury, it is understandable that there is no significant difference regarding the length of hospital stay between the two procedures. However, statistical heterogeneity was present, which may be a reflection of differences in hospital discharge protocols and the way in which the length of hospital stay was determined in these studies.

Our meta-analysis had several limitations. The small number of studies and the restricted sample size of most trials implied that the quantitative analysis was not very powerful. Moreover, the limited follow-up time of the included studies and different outcome measures considered may also have led to biased results. Large multicenter studies based on commonly accepted endpoints with long-term follow-up are warranted to compare better the results of these two different techniques of hemorrhoidectomy.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis supports that both SH and LH are probably equally valuable techniques in modern hemorrhoid surgery. However, LH might have slightly favorable immediate postoperative results and technical advantages.

COMMENTS

Background

Many clinical trials have shown that stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) and LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy (LH) have some advantages over conventional hemorrhoidectomy. However, there is still a lack of evidence comparing the clinical outcomes between SH and LH.

Research frontiers

Around 5% of the general population has hemorrhoidal disease to some extent, especially those > 40 years of age. There is a vast number of available therapeutic methods, but hemorrhoidectomy is well established as the most effective and definitive treatment for grades 3 and 4 symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease. SH and LH are new techniques that promise a less painful course and faster recovery.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Meta-analyses of clinical trials have shown that SH and LH have some advantages over conventional hemorrhoidectomy. There is still a lack of evidence focusing on the operative and postoperative outcomes of SH and LH. The present meta-analysis suggested that the operating time of SH was significantly longer than that of LH. The incidence of residual skin tags, prolapse and recurrence were significantly lower in LH than in SH.

Applications

The present meta-analysis showed that LH was more favorable than SH for patients with concomitant external hemorrhoid components and skin tags due to its slightly favorable technical advantages and immediate postoperative results, such as shorter operating time and lower occurrence of residual skin tags, prolapse and postoperative recurrence.

Terminology

SH (also known as PPH) was introduced by Longo in 1998, and uses a specially designed circular stapling instrument to excise a ring of redundant rectal mucosa or expanded internal hemorrhoids. LH uses the LigaSure vessel sealing system that consists of a bipolar electrothermal hemostatic device that allows complete coagulation of vessels up to 7 mm in diameter with minimal surrounding thermal spread and limited tissue charring.

Peer review

this study is very important meta-analysis for recently invented methods of treatment of hemorrhoid. This report is worthy for publication.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Kim YJ, Messina F, Milone M S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Arslani N, Patrlj L, Rajković Z, Papeš D, Altarac S. A randomized clinical trial comparing Ligasure versus stapled hemorrhoidectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:58–61. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318247d966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen Z. Symposium on outpatient anorectal procedures. Alternatives to surgical hemorrhoidectomy. Can J Surg. 1985;28:230–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cataldo P, Ellis CN, Gregorcyk S, Hyman N, Buie WD, Church J, Cohen J, Fleshner P, Kilkenny J, Ko C, et al. Practice parameters for the management of hemorrhoids (revised) Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0921-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milligan ETC, Naunton Morgan C, Jones L, Officer R. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal, and the operative treatment of hemorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;230:1119–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson JA, Heaton JR. Closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1959;2:176–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02616713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisinda G, Civello IM, Maria G. Haemorrhoidectomy: painful choice. Lancet. 2000;355:2253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowsell M, Bello M, Hemingway DM. Circumferential mucosectomy (stapled haemorrhoidectomy) versus conventional haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:779–781. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cirocco WC. Life threatening sepsis and mortality following stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Surgery. 2008;143:824–829. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lal P, Kajla RK, Jain SK, Chander J, Ramteke VK. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy: a technique for applying the crucial purse string suture (MAMC Technique) Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:500–503. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3180f634f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correa-Rovelo JM, Tellez O, Obregón L, Miranda-Gomez A, Moran S. Stapled rectal mucosectomy vs. closed hemorrhoidectomy: a randomized, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1367–1374; discussion 1367-1374. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulimaris I, Kanellos I, Christoforidis E, Mantzoros I, Odisseos Ch, Betsis D. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy compared with Milligan-Morgan excision for the treatment of prolapsing haemorrhoids: a prospective study. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:621–625. doi: 10.1080/11024150201680009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milito G, Cadeddu F, Muzi MG, Nigro C, Farinon AM. Haemorrhoidectomy with Ligasure vs conventional excisional techniques: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nienhuijs S, de Hingh I. Conventional versus LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy for patients with symptomatic Hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006761. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006761.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastakov MY, Buettner PG, Ho YH. Updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing conventional excisional haemorrhoidectomy with LigaSure for haemorrhoids. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:229–239. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JS, You JF. Current status of surgical treatment for hemorrhoids--systematic review and meta-analysis. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:488–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Tugwell P, Moher M, Jones A, Pham B, Klassen TP. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised trials: implications for the conduct of meta-analyses. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:i–iv, 1-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basdanis G, Papadopoulos VN, Michalopoulos A, Apostolidis S, Harlaftis N. Randomized clinical trial of stapled hemorrhoidectomy vs open with Ligasure for prolapsed piles. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:235–239. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Lai DM, Yang B, Zhang L, Zhou TC, Chen GX. [Therapeutic comparison between procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids and Ligasure technique for hemorrhoids] Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Zazhi. 2007;10:342–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraemer M, Parulava T, Roblick M, Duschka L, Müller-Lobeck H. Prospective, randomized study: proximate PPH stapler vs. LigaSure for hemorrhoidal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1517–1522. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakr MF, Moussa MM. LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy versus stapled Hemorrhoidopexy: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1161–1167. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181e1a1e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattana C, Coco C, Manno A, Verbo A, Rizzo G, Petito L, Sermoneta D. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy and Milligan Morgan hemorrhoidectomy in the cure of fourth-degree hemorrhoids: long-term evaluation and clinical results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1770–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayaraman S, Colquhoun PH, Malthaner RA. Stapled versus conventional surgery for hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005393. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005393.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oughriss M, Yver R, Faucheron JL. Complications of stapled hemorrhoidectomy: a French multicentric study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)80798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CW, Kang JC, Wu CC, Hsiao CW, Jao SW. Modified Longo’s stapled hemorrhoidopexy with additional traction sutures for the treatment of residual prolapsed piles. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:237–241. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho YH, Cheong WK, Tsang C, Ho J, Eu KW, Tang CL, Seow-Choen F. Stapled hemorrhoidectomy--cost and effectiveness. Randomized, controlled trial including incontinence scoring, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound assessments at up to three months. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1666–1675. doi: 10.1007/BF02236847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boccasanta P, Capretti PG, Venturi M, Cioffi U, De Simone M, Salamina G, Contessini-Avesani E, Peracchia A. Randomised controlled trial between stapled circumferential mucosectomy and conventional circular hemorrhoidectomy in advanced hemorrhoids with external mucosal prolapse. Am J Surg. 2001;182:64–68. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correa-Rovelo JM, Tellez O, Obregón L, Duque-López X, Miranda-Gómez A, Pichardo-Bahena R, Mendez M, Moran S. Prospective study of factors affecting postoperative pain and symptom persistence after stapled rectal mucosectomy for hemorrhoids: a need for preservation of squamous epithelium. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:955–962. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6693-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortiz H, Marzo J, Armendáriz P, De Miguel M. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs. diathermy excision for fourth-degree hemorrhoids: a randomized, clinical trial and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:809–815. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0861-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JY, Lu CY, Tsai HL, Chen FM, Huang CJ, Huang YS, Huang TJ, Hsieh JS. Randomized controlled trial of LigaSure with submucosal dissection versus Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy for prolapsed hemorrhoids. World J Surg. 2006;30:462–466. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheetham MJ, Mortensen NJ, Nystrom PO, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Persistent pain and faecal urgency after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;356:730–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganio E, Altomare DF, Gabrielli F, Milito G, Canuti S. Prospective randomized multicentre trial comparing stapled with open haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:669–674. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shalaby R, Desoky A. Randomized clinical trial of stapled versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1049–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speakman CT, Burnett SJ, Kamm MA, Bartram CI. Sphincter injury after anal dilatation demonstrated by anal endosonography. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1429–1430. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramcharan KS, Hunt TM. Anal stenosis after LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1670–1671; author reply 1671. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seow-Choen F, Ho YH, Ang HG, Goh HS. Prospective, randomized trial comparing pain and clinical function after conventional scissors excision/ligation vs. diathermy excision without ligation for symptomatic prolapsed hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1165–1169. doi: 10.1007/BF02251970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corman ML, Gravié JF, Hager T, Loudon MA, Mascagni D, Nyström PO, Seow-Choen F, Abcarian H, Marcello P, Weiss E, et al. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy: a consensus position paper by an international working party - indications, contra-indications and technique. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:304–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravo B, Amato A, Bianco V, Boccasanta P, Bottini C, Carriero A, Milito G, Dodi G, Mascagni D, Orsini S, et al. Complications after stapled hemorrhoidectomy: can they be prevented? Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s101510200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sayfan J, Becker A, Koltun L. Sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy: a new technique. Ann Surg. 2001;234:21–24. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho YH, Seow-Choen F, Tsang C, Eu KW. Randomized trial assessing anal sphincter injuries after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1449–1455. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayne DG, Botterill I, Ambrose NS, Brennan TG, Guillou PJ, O’Riordain DS. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus conventional diathermy for day-case haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:428–432. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2002.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters CJ, Botterill I, Ambrose NS, Hick D, Casey J, Jayne DG. Ligasure trademark vs conventional diathermy haemorrhoidectomy: long-term follow-up of a randomised clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:350–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gravante G, Venditti D. Postoperative anal stenoses with Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy. World J Surg. 2007;31:245; author reply 246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]