Abstract

Background:

Essential oils have been used as an alternative and complementary treatment in medicine. Citrus fragrance has been used by aromatherapists for the treatment of anxiety symptoms. Based on this claim, the aim of present study was to investigate the effect of aromatherapy with essential oil of orange on child anxiety during dental treatment.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty children (10 boys, 20 girls) aged 6-9 years participated in a crossover intervention study, according to the inclusion criteria, among patients who attended the pediatric department of Isfahan Dental School in 2011. Every child underwent two dental treatment appointments including dental prophylaxis and fissure-sealant therapy under orange aroma in one session (intervention) and without any aroma (control) in another one. Child anxiety level was measured using salivary cortisol and pulse rate before and after treatment in each visit. The data were analyzed using t-test by SPSS software version 18.

Results:

The mean ± SD and mean difference of salivary cortisol levels and pulse rate were calculated in each group before and completion of treatment in each visit. The difference in means of salivary cortisol and pulse rate between treatment under orange odor and treatment without aroma was 1.047 ± 2.198 nmol/l and 6.73 ± 12.3 (in minutes), which was statistically significant using paired t-test (P = 0.014, P = 0.005, respectively).

Conclusion:

It seems that the use of aromatherapy with natural essential oil of orange could reduce salivary cortisol and pulse rate due to child anxiety state.

Keywords: Aromatherapy, children, dental anxiety, orange essential oil, salivary cortisol

INTRODUCTION

Dental fear and anxiety have been perceived as a score of complication in managing pediatric patients.[1] A long-term avoidance of dental treatment due to dental anxiety may decline the state of oral health,[2] resulting in pain and distress.[3] Incidence of dental caries can be predicted by dental anxiety.[4] In addition, anxious patients are more sensitive to pain.[5] Helping patients overcome fear and anxiety may increase regular and scheduled dental visits[6] and may ultimately improve the quality of life.[7,8]

There are anxiety-provoking factors in a dental setting, such as the sights (needles), sounds (drilling), smells (cut dentine, eugenol), and sensation (high-frequency vibration).[3,9] According to several researches, odors can modulate cognition,[10] mood,[11] and behavior.[12] There is a powerful connection between odors and memories, especially those from the distant past, charged with emotional significance due to major anatomical connections existing between brain structures such as the hypothalamus and limbic system which are involved in emotion and memory.[13] The smell of the dental office was found to be highly effective in a study evaluating dental fear and anxiety.[14] In another study, this item has shown high scores in patients with dental phobia.[15]

Recently, contemporary and alternative medicine approaches such as aromatherapy (use of essential oils, scented, volatile liquid substances for therapeutic purposes) have been considered in dental[16,17,18,19] and medical settings.[20,21,22,23] This method is supporting the concept that common oils can produce positive pharmacological and physiological effect by the sense of smell.[24] For instance, the parasympathetic nervous system activity is increased by 12% and sympathetic activity is decreased by 16% with orange oil.[25] Faturi et al. declared an acute anxiolytic effect of sweet orange essence in rats, and in order to discard the possibility that this effect was a result of exposure to any other odor, the behavioral response to another Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil was also assessed. They supported the use of orange essential oil by aromatherapists as a tranquilizer.[26]

The effect of aromatherapy on dental anxiety has been assessed in a few studies. Lehrner et al. studied the effect of orange odor and reported improved mood and less anxiety only in females.[18] Five years later, in another study, they compared the effect of orange and lavender odor with a music condition and a control condition and demonstrated that odors are capable of reducing anxiety and altering emotional states in dental patients.[19] In a cluster randomized controlled trial, Kritsidima et al. explained reduced state of anxiety with lavender scent in dental patients.[17] Ndao et al. studied the effect of inhalation aromatherapy and stated that respiratory administration of bergamot essential oil did not decrease anxiety, nausea, and pain when added to standard supportive care.[22] Muzzarelli et al. recommended that aromatherapy can be more useful at a moderate level of anxiety;[27] however, in a study conducted by Toet et al., the use of orange and apple odors did not reduce anticipatory anxiety and did not improve mood of patients waiting for scheduled visits in large dental clinics.[28] In a study performed by Maura et al., the effect of gender and ethnicity on preferences and attitudes in children was investigated. They reported that children are very different from adults in their odors and taste preferences and they are likely to use essential oils which they find pleasant. They found aromatherapy appealing and acceptable for school age children. They concluded that specific essential oils are accepted by children, such as sweet orange or lemon.[29]

It is admitted that psychological stress can largely influence physiological systems such as autonomic system and the hypothalamus–pituitary adrenal axis (HPA axis) stimuli. The HPA axis activity enhances in situations including anxiety and pain which result in increasing cortisol secretion. Dental stimuli have the potential of inducing anxiety.[30] Cortisol is released from the cortex of the adrenal and diffused to all body fluids. It can be discovered in urine, serum, and saliva.[31] Salivary samples have many advantages such as noninvasiveness, stability at room temperature up to a week, and independency of its concentration on salivary flow rate,[30] and also pulse rate recording is simple and practical, which are the reasons for selecting salivary cortisol and pulse rate for child anxiety assessment.[32]

Because of the importance of anxiety control, the inconsistency in studies conducted so far, the lack of investigations in pediatric population, and property of aromatherapy that is inexpensive and noninvasive, we designed a randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate the effect of aromatherapy with essential oil of orange on salivary cortisol and pulse rate as indicators for child anxiety during dental treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a randomized controlled clinical trial, the effects of orange odor on child anxiety during dental treatment were evaluated. This study has been registered under Iranian Registry for Clinical Trials (IRCT: 201201258821N1).

Thirty children (10 boys, 20 girls), aged between 6 and 9 years, were selected among patients who attended the pediatric department of dental school in 2011 by convenient sampling according to the following criteria. The inclusion criteria used for selecting the patients were: children aged 6–9 years, who had two permanent molars which needed fissure-sealant therapy and were Frankle + in cooperation (children who accept treatment with cautious behavior at times; willing to comply with the dentist, at times with reservation, but follow the dentist's direction cooperatively are Frankle +),[33] with the absence of any systemic problems, physical and mental disabilities, and those who did not have any previous dental visit. Children with common cold and allergy were excluded from this study. Prior to the session, an informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians and they completed a form containing children's medical information.

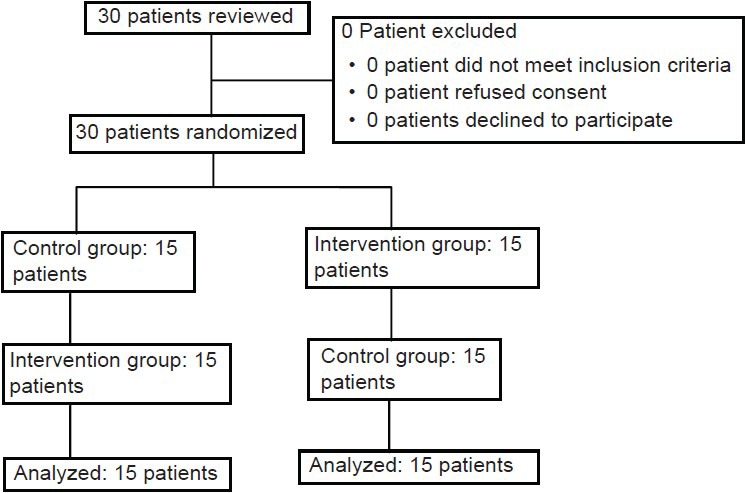

In this crossover design study, participants were assigned into two groups by even–odd method by a dental practice secretary who was blind to the aim and design of study. Half of the children were treated without any odor (control) initially and received orange aroma in the second session (intervention). Another 15 children received treatment under orange aroma in the first encounter (intervention) and treated without any aroma at the second visit (control). [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Patients who entered the study were divided into the study groups and analyzed

The natural essential oil of orange (Citrus sinensis) supplied by Giah essence corporation (Gorgan, Iran) was used. The main components of essential oil were determined by gas chromatography, which were found to be limonene 92%, myrcene 3%, and other components 5%, and most of them were α-pinene, β-pinene, p-cymene, linalool, and geraniol. This data was provided by the delivering company.

Aftab electrical aroma diffuser (Rayehe pardazan pishtaz, Tehran, Iran) was used to pass a stream of air driven by a fan to diffuse essential oils, while it was out of sight of the participants. Considering the size of the operating room which was 10 m2, based on the clinical experience and in order to receive orange odor with constant intermediate concentration, 2 ml of orange essence was stored in an identical glass bottle that was placed under a small fan in a dispenser and the timer was set so that it was activated for 2 min every 10 min. All the actions were performed half an hour before the first patient's arrival in aromatherapy days. The control groups were scheduled on different days and water was stored in the diffuser instead of aromatic oil.

Every child needed two treatment appointments and all children were treated between 8 and 9 a.m. and the second visit was in the following week at the same time. During each visit, first the child was separated from his/her parents by a nurse and carried to a room. After 5 min, a nurse who was trained and calibrated for sampling recorded the pulse rate by a finger type pulse oximeter (Nonin, Chicago, USA) and also collected unstimulated saliva by placing an absorbent cotton pellet (Salivette, Sarstedt Inc., Newton, NC, Chicago, USA) sublingually. After 5 min, it was taken out and placed in a polypropylene coated tube and was numbered as the first sample of that child. Then, the child was taken to the operating room. We used the same dental procedure in both appointments, which was a routine fissure-sealant therapy performed by a senior postgraduate student of pediatric dentistry, consisting of the tooth being cleaned with a low-speed dental hand piece and a rotary bristle brush and then performing fissure-sealant therapy for one of the permanent first molars. After the completion of treatment, the nurse sampled saliva and recorded pulse rate and labeled it as the second sample. Two samplings of each visit took place in different locations and there was about 20 m distance between them in order to omit the effect of ambient odor on the first sampling. In the other visit, dental treatment was done and sample was taken following the same procedure, and third and fourth samples were collected. By collecting four samples of each child, a total of 120 samples were obtained. At the end of each appointment, the samples were sent to the laboratory. Saliva samples were centrifuged and stored frozen at −20°C until adequate samples were ready for analysis. The salivary cortisol level was detected using Immunoassay cortisol kit by Elecsys cortisol assay (ECLIA-68298, Roche diagnostic GMBH-BD, Sandhofer, Germany).

Paired t-test was considered for main effect analysis; carryover effect and period effect were analyzed using Student's t-test by the SPSS statistical package (Version 18, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-value <0.05 was considered as the level of significance.

RESULTS

Thirty children with the mean age of 7.66 ± 0.84 years participated in this study. They were assigned randomly in two groups according to crossover design. The first group consisted of 15 children (9 girls and 6 boys) with the mean age of 7.80 ± 0.86 years, who were treated in the absence of orange aroma in the first session (control) and under orange aroma in the second one (intervention). The second group consisted of 11 girls and 4 boys, with the mean age of 7.53 ± 0.83 years, who were treated under orange aroma in the first encounter (intervention) and without odor in the second one (control). There was no statistically significant difference in age between the two groups (P = 0.396). Also, there was no statistically significant difference in number of boys and girls in this study (P = 0.439)

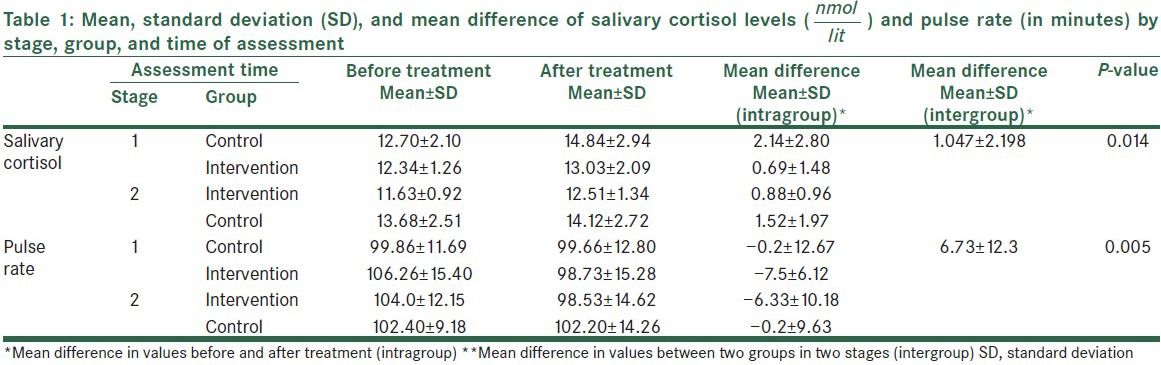

Anxiety of children was assessed with salivary cortisol level and pulse rate before and on completion of each dental appointment. The mean ± SD of salivary cortisol levels were calculated in each group before and on completion of treatment in each visit. In addition, the mean difference of salivary cortisol level was obtained by calculating the difference in cortisol level values before treatment and on completion of treatment in each visit (end of treatment – before treatment), which are presented in Table 1.

The main effect of this study was obtained by calculating the difference of salivary cortisol means between treatment under orange aroma and treatment without aroma, which was 1.047 ± 2.198 nmol/l and statistically significant using paired t-test (P = 0.014) [Table 1].

Table 1 shows the mean ± SD of pulse rate before and after treatment in both stages and visits. In addition, the mean difference of pulse rate was obtained by calculating the pulse rate differences before and after treatment (end of treatment – before treatment).

The other main effect of this study was obtained by the calculating difference of pulse rate means between treatment under orange aroma and without aroma, which was 6.73 ± 12.3 (in minutes) and statistically significant using paired t-test (P = 0.005) [Table 1].

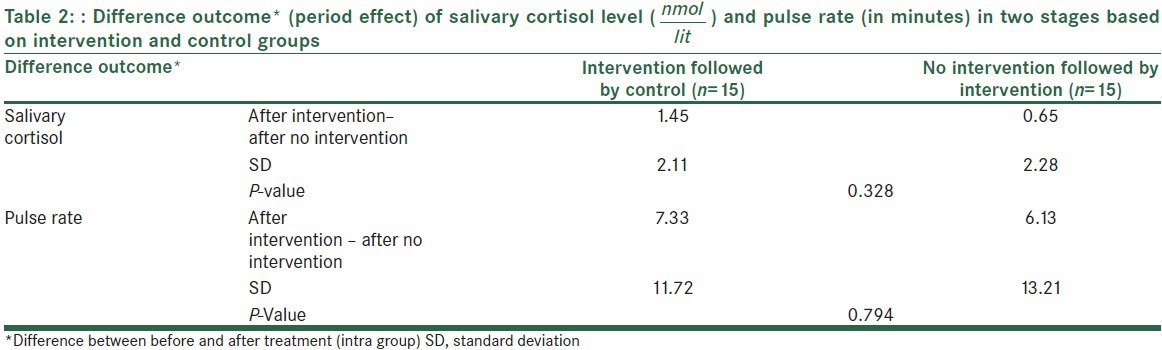

The difference between before and after treatment (intra group) of salivary cortisol level and pulse rate (after treatment in the presence of orange aroma − after treatment in the absence of orange aroma) in patients treated under orange aroma that was followed by the absence of aroma, and also in patients treated in the absence of aroma that was followed by orange aroma were obtained [Table 2].

Period effect was not statistically significant in salivary cortisol level and pulse rate (P = 0.328 and 0.794, respectively). It shows that there was no statistically significant difference between salivary cortisol levels and pulse rates of children who were treated under orange aroma in the first visit and without intervention at the second one and those who were treated without orange aroma in the first visit and with intervention at the second one.

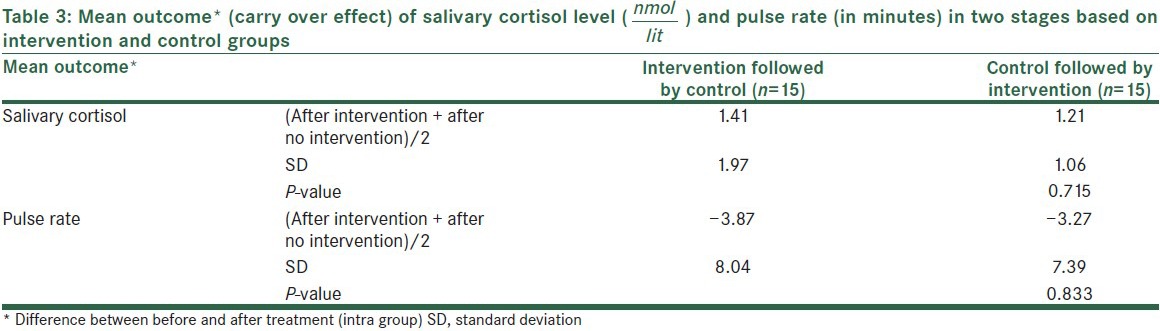

Table 3 shows the mean difference between before and after treatment (intra group) of salivary cortisol level and pulse rate in treatment under orange aroma that followed by the absence of aroma and also, in treatment in the absence of aroma that followed by orange aroma (after intervention + after no intervention)/2). Carry over effect were not statistically significant for salivary cortisol level and pulse rate. (P value = 0.715 and 0.833 respectively).It declared that wash out period was convenient.

DISCUSSION

This study had a new approach toward aromatherapy that was accompanied with dental treatment in children, based upon the anxiolytic effect of orange odor. The results of this study showed that the salivary cortisol level and pulse rate decreased in intervention groups by using aromatherapy and that these differences were statistically significant.

On inhalation of scented oils, volatile molecules of the oil reach the lungs and rapidly diffuse into the blood, causing brain activation via systemic circulation.[34] However, these molecules also bind to olfactory receptors, creating an electrophysiological response which reaches the brain. Neocortex activation is expected to occur by this response, which has an effect on perception of odors and reaches the limbic system regions including amygdale and hypothalamus, the areas where levels of hormone and emotions are controlled.[35,36] Thus, the salivary cortisol level and pulse rate decrease as mentioned above, following aromatherapy.

The result of the present study is in agreement with the results obtained in the 2000 and 2005 studies by Lehrner et al. and 2010 study by Kritsidima et al.[17,18,19]

While choosing a stressor, dental treatment including oral prophylaxis and fissure-sealant therapy were selected because of their convenience, noninvasiveness, and ethical nature. Because these two procedures are painless, it was supposed that any changes in salivary cortisol and pulse rate might be as a result of stress and not because of pain.

Limonene was the main component of this natural essential oil of orange, as determined by gas chromatography. This was near to limonene concentration in orange essential oil used in studies by Lehrer et al. and the animal study by Future et al.[18,19,26] It is possible that limonene is responsible for reducing anxiety in these studies.

Salivary cortisol was measured in studies by Kanegane et al. in assessing dental anxiety before urgent dental care, Toda et al. for evaluating the effect of lavender aroma on endocrinological stress markers, and Atsumi et al. in investigating smelling lavender and rosemary.[37,38,39] Pulse rate was recorded in previous studies by Westra et al. in evaluating discomfort in children who underwent unsedated magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and by Chang and Shen in assessing aromatherapy on elementary school teachers.[32,40]

All aromatherapy studies in dental environments so far conducted in waiting rooms and the anticipatory anxiety of patients was evaluated. These studies included adults of a wide age range and anxiety was assessed by questionnaires.[17,18,19] Because of the parallel design of these studies, case and control groups could be different at baseline, and also, they presented for different dental treatments (dental cleaning, drilling, root canal therapy). In addition, it is not clear that reduced anxiety in waiting room due to aromatherapy can be effective on anxiety during seating on a dental chair.

However, the present study is different from the results reported by Toet et al., Ndao et al., Nord and Belew, and also by Holm and Fitzmaurice.[22,23,28,41] Toet et al. reported that additional distraction sources in the waiting rooms of large dental clinics, such as great background activity and continuous going and coming of patients, might influence the outcome.[28]

Ndao et al. used bergamot essential oil in children and adolescents who underwent stem cell infusion. Bergamot essential oil induced dose-related sequence of sedative and stimulatory behavior effect in animal models.[22] It was possible that the administered dose in this study induced more stimulatory rather than sedating effect. Also, patients with different diagnosis and treatment histories were included in this study. Nord and Belew reported that the children's comfort in a perianesthesia setting was enhanced by using lavender and ginger essential oils, which was not statistically significant. The samples in this study included children with and without developmental disabilities. Faces, Legs, Arms, Cry, and Consolability (FLACC) scale was used in this study, which was performed by parents. As a strategy for blinding, parents were not trained for this scale. Thus, their reports were not reliable.[23] Holm and Fitzmaurice stated that anxiety of adults who accompanied children to a pediatric emergency department decreased by music compared with aromatherapy. This might be due to imprecise application of the aromatherapy or environmental conditions.[41]

According to the cognitive and developmental alterations and aging effects on children's preferences, focus on an age group should be taken into consideration. This study was the first to investigate the anxiolytic effect of aromatherapy on children during dental treatments. Only 6–9-year-old children who are nearly in concrete operation of Piaget's stage participated in this study.[29] Some consistency was obtained in development by selecting this age range and this investigation was made comparable with other studies. As parental anxiety may affect the children's anxiety and alter under aromatherapy,[42] we did not permit parents to accompany their children.

It has been reported by some studies that the smell of eugenol which is present in the dental environment may influence dental care in some patients and produce strong unpleasant feelings like fear and anxiety.[15] According to our inclusion criteria, the children selected had lack of any previous dental visit; therefore, the need for masking the smell of eugenol was not felt in our present study.

CONCLUSION

Although this randomized control trial provides evidence in favor of the use of orange essential oil in dental settings by reducing salivary cortisol and pulse rate due to child anxiety state, further studies can be taken up with larger sample size, in children of lower age range, and in children with history of dental treatment. Assessing the influence of aromatherapy on more complex and fearful dental procedures including injection of local anesthesia and drilling is recommended in future studies. Water was used in the present study as control; using a control odor without therapeutic properties as placebo can be more useful and precise in future researches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was approved by Chancellor for Research, School of Dentistry, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, and has no conflict with Helsinki Declaration (Grant #390146). This study was funded by School of Dentistry, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Helsinki Declaration (Grant #390146)

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Bare LC, Dundes L. Strategies for combating dental anxiety. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:1172–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng X, Heft MW, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Effect of fear on dental utilization behaviors and oral health outcome. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh LJ. Anxiety prevention: Implementing the 4 S principle in conservative dentistry. Auxiliary. 2007;17:24–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taani DQ, El-Qaderi SS, Abu Alhaija ES. Dental anxiety in children and its relationship to dental caries and gingival condition. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:83–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2005.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lahmann C, Schoen R, Henningsen P, Ronel J, Muehlbacher M, Loew T, et al. Brief relaxation versus music distraction in the treatment of dental anxiety: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:317–24. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loggia ML, Schweinhardt P, Villemure C, Bushnell MC. Effects of psychological state on pain perception in the dental environment. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:651–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S, Fiske J, Newton J. Behavioural dentistry: The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Br Dent J. 2000;189:385–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locker D. Psychosocial consequences of dental fear and anxiety. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:144–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oosterink F, De Jongh A, Aartman IH. What are people afraid of during dental treatment? Anxiety-provoking capacity of 67 stimuli characteristic of the dental setting. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:44–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millot JL, Brand G, Morand N. Effects of ambient odors on reaction time in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2002;322:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goel N, Grasso DJ. Olfactory discrimination and transient mood change in young men and women: Variation by season, mood state, and time of day. Chronobiol Int. 2004;21:691–719. doi: 10.1081/cbi-200025989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millot J, Brand G. Effects of pleasant and unpleasant ambient odors on human voice pitch. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:61–3. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aggleton JP, Mishkin M. The amygdala: Sensory gateway to the emotions. Emotion. 1986;3:281–99. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinknecht R, Klepac R, Alexander LD. Origins and characteristics of fear of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1973;86:842. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1973.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakeberg M, Berggren U. Dimensions of the Dental Fear Survey among patients with dental phobia. Acta Odontologica. 1997;55:314–8. doi: 10.3109/00016359709114970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hainsworth J, Moss H, Fairbrother K. Relaxation and complementary therapies: An alternative approach to managing dental anxiety in clinical practice. Dent Update. 2005;32:90. doi: 10.12968/denu.2005.32.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kritsidima M, Newton T, Asimakopoulou K. The effects of lavender scent on dental patient anxiety levels: A cluster randomised-controlled trial. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:83–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehrner J, Eckersberger C, Walla P, Pötsch G, Deecke L. Ambient odor of orange in a dental office reduces anxiety and improves mood in female patients. Physiol Behav. 2000;71:83–6. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehrner J, Marwinski G, Lehr S, Johren P, Deecke L. Ambient odors of orange and lavender reduce anxiety and improve mood in a dental office. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:92–5. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evandri M, Battinelli L, Daniele C, Mastrangelo S, Bolle P, Mazzanti G. The antimutagenic activity of Lavandula angustifolia (lavender) essential oil in the bacterial reverse mutation assay. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:1381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SY. [The effect of lavender aromatherapy on cognitive function, emotion, and aggressive behavior of elderly with dementia] Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2005;35:303. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2005.35.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ndao DH, Ladas EJ, Cheng B, Sands SA, Snyder KT, Garvin JH, Jr, et al. Inhalation aromatherapy in children and adolescents undergoing stem cell infusion: Results of a placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Psychooncology. 2012;21:247–54. doi: 10.1002/pon.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nord DA, Belew J. Effectiveness of the essential oils lavender and ginger in promoting children's comfort in a perianesthesia setting. J Peri Anesth Nurs. 2009;24:307–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnaubelt K. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press; 1998. Advanced aromatherapy: The science of essential oil therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobetsberger C, Buchbauer G. Actions of essential oils on the central nervous system: An updated review. Flavour Fragr J. 2011;26:300–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faturi CB, Leite JR, Alves PB, Canton AC, Teixeira-Silva F. Anxiolytic-like effect of sweet orange aroma in Wistar rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:605–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzzarelli L, Force M, Sebold M. Aromatherapy and reducing preprocedural anxiety: A controlled prospective study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29:466. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toet A, Smeets MA, van Dijk E, Dijkstra D, van den Reijen L. Effects of pleasant ambient fragrances on dental fear: Comparing apples and oranges. Chemosens Percept. 2010;3:182–9. doi: 10.1007/s12078-010-9078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald M, Culbert T, Finkelstein M, Green M, Johnson A, Chen S. The effect of gender and ethnicity on children's attitudes and preferences for essential oils: A pilot study. Explore. 2007;3:378–85. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King SL, Hegadoren KM. Stress hormones: How do they measure up? Biol Res Nurs. 2002;4:92–103. doi: 10.1177/1099800402238334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gozansky W, Lynn J, Laudenslager M, Kohrt W. Salivary cortisol determined by enzyme immunoassay is preferable to serum total cortisol for assessment of dynamic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63:336–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westra AE, Zegers MP, Sukhai RN, Kaptein AA, Holscher HC, Ballieux BE, et al. Discomfort in children undergoing unsedated MRI. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:771–7. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baier K, Milgrom P, Russell S, Mancl L, Yoshida T. Children's fear and behavior in private pediatric dentistry practices. Pediatric Dent. 2004;26:316–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maddocks-Jennings W, Wilkinson JM. Aromatherapy practice in nursing: Literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buck LB. Smell and taste: The chemical senses. Princ Neural Sci. 2000;4:625–47. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sam M, Vora S, Malnic B, Ma W, Novotny MV, Buck LB. Neuropharmacology: Odorants may arouse instinctive behaviours. Nature. 2001;412:142. doi: 10.1038/35084137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atsumi T, Tonosaki K. Smelling lavender and rosemary increases free radical scavenging activity and decreases cortisol level in saliva. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanegane K, Penha SS, Munhoz CD, Rocha RG. Dental anxiety and salivary cortisol levels before urgent dental care. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:515–20. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toda M, Morimoto K. Effect of lavender aroma on salivary endocrinological stress markers. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:964–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang KM, Shen CW. Aromatherapy benefits autonomic nervous system regulation for elementary school faculty in Taiwan. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/946537. 946537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holm L, Fitzmaurice L. Emergency department waiting room stress: Can music or aromatherapy improve anxiety scores? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:836–8. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818ea04c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peretz B, Nazarian Y, Bimstein E. Dental anxiety in a students’ paediatric dental clinic: Children, parents and students. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2004;14:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2004.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]