Abstract

Background

Recent evidence suggests that STN-DBS may have a disease-modifying effect in early PD. A randomized, prospective study is underway to determine whether STN-DBS in early PD is safe and tolerable.

Objectives / Methods

Fifteen of thirty early PD patients were randomized to receive STN-DBS implants in an IRB-approved protocol. Operative technique, location of DBS leads, and perioperative adverse events are reported. Active contact used for stimulation in these patients were compared with 47 advanced PD patients undergoing an identical procedure by the same surgeon.

Results

Fourteen of the 15 patients did not sustain any long-term (> 3 months) complications from the surgery. One subject suffered a stroke resulting in mild cognitive changes and slight right arm and face weakness. The average optimal contact used in symptomatic treatment of early PD patients was: anterior −1.1±1.7mm, lateral 10.7±1.7mm, superior −3.3±2.5mm (AC-PC coordinates). This location is statistically no different (0.77mm, p> 0.05) than the optimal contact used in treatment of 47 advanced PD patients.

Conclusions

The perioperative adverse events in this trial of subjects with early stage PD are comparable to that reported for STN-DBS in advanced PD. The active contact position used in early PD is not significantly different from that used in late stage disease. This is the first report of the operative experience from a randomized, surgical-versus-best-medical-therapy trial for the early treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, deep brain stimulation, subthalamic nucleus, randomized surgical trial

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a relentlessly progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability. Two centuries after Parkinson’s disease was first characterized, and more than 40 years after levodopa was first used to treat symptoms of the disorder, no therapy has been proven to stop or even slow disease progression.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) targeting the subthalamic nucleus (STN) was first pioneered as a therapy for PD at the University of Grenoble in the 1980s and has been well established as an effective therapy for relief of motor symptoms in late-stage disease.[1] While the proposed mechanism of efficacy of STN-DBS remains controversial, it is widely accepted as a treatment for advanced PD when symptoms are not adequately controlled by medications.

To date, evidence of disease modification in DBS has come primarily from rodent and primate models of PD. Temel et al. found that rats treated with DBS during ongoing 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neurodegeneration demonstrated 28–30% less cell loss in the SN when compared to non-DBS control animals.[2] Wallace et al explored disease modification in the 1-methyl–4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) model of PD in primates.[3] They found that animals that had undergone stimulation of the STN both before and after MPTP-induced injury had 20% more dopaminergic cells in the SN than MPTP-treated animals that had not undergone stimulation. The mechanism for these results remains to be elucidated. Spieles-Engemann et al most recently demonstrated that STN stimulation provides neuroprotection in animals subjected to a prior significant nigral dopamine neuron loss similar to PD patients at the time of diagnosis.[4] Just as the mechanism of action for the clinical benefit of DBS remains controversial, so does the potential mechanism of DBS as a neuroprotective therapy if applied early in Parkinson’s disease. Emerging evidence now points toward increased brain derived growth factor (BDNF) production resulting from STN-DBS.[4]

Clinical studies to date have been conflicting. Early observations by physicians at the University of Grenoble, France, of patients enrolled in the first clinical trials of DBS suggested that some patients experienced stabilization of PD symptoms following DBS as opposed to typical progression (A.L. Benabid, unpublished data). This observation is supported by a more recent trial of STN-DBS in patients with advanced PD.[5] The authors found that Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores in the stimulation off and medication off state, measured 4 years after implantation, were not significantly different from baseline. Neuroprotection, however, was not one of the stated endpoints of the study. Other studies, however, have noted significant deterioration in patients who have undergone DBS, both with respect to motor symptoms [1] and cytopathologic analysis.[6] These studies have been limited by the fact that they have not included a control group treated only with standard drug therapy for comparison. Furthermore, they have investigated only cohorts of patients with advanced disease, at a point when considerable cell death has already occurred in the SN, and disease-modifying interventions are unlikely to demonstrate any significant benefit.

Even in the absence of solid clinical evidence, a number of clinicians are trending toward earlier surgical intervention in patients with PD. Rigorous prospective clinical studies are therefore necessary to determine, first, whether STN-DBS in early PD is safe and tolerable and, second, whether the intervention imparts a disease-modifying effect.

We are conducting a prospective, randomized, single-blind, pilot study of STN DBS in thirty subjects with early stage PD.[7] (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00282152, IRB 040797, FDA Investigation Device Exemption). This study is designed to collect necessary preliminary data to launch a large-scale, multi-center trial to determine if STN-DBS will have a disease modifying effect if applied in early stage PD. Subjects are randomized to best medical therapy with (n=15) or without (n=15) DBS. The study completed enrollment of all thirty subjects, of which 15 study participants have received bilateral STN-DBS.

In this paper, we report on the surgical experience of the 15 subjects receiving DBS, including operative technique, final position of the DBS leads, and perioperative adverse events. We also retrospectively reviewed the effective lead contact location for 47 advanced PD patients undergoing identical DBS implantation surgery for symptomatic treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Early Parkinson’s Disease Group

Fifteen subjects (14 males, 1 female; average age: 60 ± 6 years), were randomized to the surgical arm of this study and implanted with bilateral STN DBS. Inclusion criteria are age 50 – 75 years; treatment with antiparkinsonian medications (levodopa or dopamine agonists) for greater than 6 months, and less than 4 years; demonstrated response to dopaminergic therapy (>30% improvement in motor symptoms on medication versus off medication, based on UPDRS-III motor examinations sub-score); Hoehn and Yahr Stage II (off medication); absence of motor fluctuations or dyskinesias; no evidence of an alternative diagnosis or secondary parkinsonism; and no surgical contraindications. The mean motor score on the UPDRS-III was 25.7 +/− 8.7 off medication and 13.8 +/− 8.5 on medication. All subjects provided informed consent prior to enrollment or any study procedures being performed.

Advanced Parkinson’s Disease Group

Forty-seven advanced Parkinson’s disease patients were retrospectively reviewed for comparison of lead location. These Parkinson’s patients had the following characteristics: Hohn and Yahr III or IV, mean age 59.9 +− 9.0 years. UPDRS scores were not available post-operatively in these patients. However, these patients were operated on by the same surgeon during the years 2002–2008 using the same surgical technique for determination and placement of bilateral STN electrodes as with the early PD patients.

Surgery/Operative Technique

We utilize the WayPoint™ rapid-prototyped stereotactic system (FHC Inc; Bowdoin, ME) for implantation of all DBS electrodes at Vanderbilt University since 2002, which has been described elsewhere.[8,9] Briefly, the surgical implantation of a DBS system using this methodology encompasses three steps: 1) preoperative imaging, placement of bone fiducial markers, and preoperative target planning and trajectory assignment; 2) stereotactic mapping of the STN nucleus bilaterally with subsequent placement of the DBS electrodes; and 3) implantation of bilateral single channel internal pulse generators (IPGs). Each step is separated by approximately one week; the first and the last steps are outpatient procedures, whereas the second step was performed as an inpatient procedure.

During the first procedure involving outpatient imaging and placement of bone fiducial markers, the operative targets, entry points, and identification of landmarks such as anterior and posterior commissures were completed by the neurosurgeon utilizing the WayPoint™ stereotactic software (FHC Inc, Bowdoin, ME). STN target selection was arrived at based on consideration of normal AC-PC coordinates for STN, indirect targeting methods,[10] and previous successful STN target implants by the surgeon (PK). Use of the WayPoint™ stereotactic software planning algorithm includes access to a unique, normalized physiological atlas database located at Vanderbilt University under development through a separate research initiative (NIH-NIBIB 1 R01-EB006136).[11] The stereotactic planning software allows the display of previously implanted DBS electrodes by the surgeon to be overlaid on a patient’s MRI along with AC-PC coordinates. Therefore, the locations of previous DBS implants that were successfully implanted in the STN of advanced PD patients were accessible to the surgeon for target planning on all 15 early PD patients being implanted. Furthermore, the same physiological atlas database was used to store the initial AC-PC coordinates as well as X, Y, Z locations for intended STN targets with respect to pre-operative MRI images for every patient in this study.

Prior to the second procedure by which the STN nucleus is mapped and implanted, dopamine agonists were discontinued forty-eight hours prior to surgery, and all other antiparkinsonian medications were discontinued twenty-four hours prior to surgery. On the day of surgery, the patient was placed in a semi-recumbent position in the operating room and the scalp was injected with local anesthetic and prepped with sterile solution. Low dose dexmedetomidine and remifentanil were used as additional analgesia in minimal amounts during placement of the burr hole. A burr hole and durotomy served to expose the surface of the brain, and the microTargeting™ platform was affixed to bone anchors placed previously. Arrays of 2–4 tungsten microelectrodes (1MΩ @ 1kHz) were placed in guide tubes in a “Ben-gun” configuration and advanced with microTargeting™ electrode drives (FHC Inc., Bowdoin, ME).[12]

MER was performed using either the Leadpoint™ (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) or Guideline4000™ (FHC Inc., Bowdoin, ME) recording system. All MER data was digitally sampled (24 kHz), bandpass filtered (0.5 – 5 kHz), amplified, displayed, and digitally stored. Microelectrodes were advanced toward the STN along the predefined trajectory. Ten second recordings were made at regular (0.5 – 1.0 mm) intervals, beginning at 10 mm above the target and ending at 5 mm below the target or at the dorsal border of the substantia nigra pars reticularis (SNr). Recordings from the STN and the SNr were interpreted based on accepted criteria by a neurophysiologist (CCK or MSR) in the operating room.[12–17] The superior border of the STN was easily defined by observing significant increase in background activity (neuronal noise) and the rate of irregularly firing neurons as well as evidence for motor somotatotopy. The coordinates of the STN and SNr borders were recorded in the physiological atlas.

A neurologist (PDC) trained in movement disorders then performed intraoperative neurological examination to map the response to micro-stimulation in order to define the stimulation thresholds for symptom relief and side effects. Stimulation was delivered through a 0.46 mm × 1.0 mm contact referenced to a ground electrode. A Grass Technologies S88 stimulator (Astro-Med, Inc., West Warwick, RI) was used as a constant voltage source (150µs cathodal pulses at 150Hz). Stimulation parameters delivered to the patient were confirmed using an oscilloscope and recorded for each position tested in the patient and correlated with MRI image space for every patient.

Determination of optimal stimulation target was determined by consensus opinion of the neurosurgeon, neurologist and neurophysiologist before implantation of the DBS lead. During each surgery, microelectrode recordings (MERs), stimulation responses, and final lead location were determined, and these data were entered into a physiological atlas database and assigned a three-dimensional location on the subject’s MRI image.[11,18] Once the final target was determined, the test electrode was removed and replaced with a permanent lead (Model 3389; Medtronic Neurological, Inc.; Minneapolis, MN). This lead was tested for functionality, affixed to the skull, and proximal end coiled under the scalp. The procedure was then repeated for the contralateral hemisphere on the same day. Following placement of the permanent DBS electrode, the bone fiducial markers were removed and all incisions closed. Patients were allowed to recover overnight in the hospital and were expected to be discharged the following day.

Within 10 days from placement of the DBS lead, an implanted pulse generator (Model #7426 – Soletra™, Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) was placed in a subclavicular pocket and connected to the permanent electrodes for stimulation. At a follow up visit a neurologist adjusted the parameters of stimulation by programming the IPG. This involved selecting the optimal stimulation contact(s) among four possible for each lead, and adjusting the parameters including voltage, pulse width and frequency. These settings were optimized to produce the greatest therapeutic benefit and least amount of side effects.

Once all subjects were implanted, a normalized reference MRI volume (AtlasePD) was created from the 15 subjects’ MRI T1 scans and intraoperative data using a non-rigid deformation algorithm.[11] These data were then compared to a normalized brain volume as well as to traditional anterior and posterior commissure (AC-PC) coordinates.

Adverse Events Analysis

We are prospectively collecting all adverse events and these are reviewed on regular intervals by the data safety monitoring board and provided to the Food and Drug Administration. We report here all adverse events from placement of fiducial bone markers to final discharge following IPG implantation.

Statistical Analysis

The optimal location for stimulation was determined both by the intraoperative placement of the lead and the postoperative programming of the implant, and was defined by the position of the specific contacts used for stimulation. In order to account for differences between patients, each data point was normalized by registering the patients’ MRIs rigidly and non-rigidly [19] onto the AtlasePD before creating the statistical analysis. Briefly, we chose to use a mathematical deformation algorithm developed by Rhode et al [19] as method to collate target locations for physiological points of interest, such as the optimal stimulus location for rigidity reduction in these study patients. This algorithm has allowed us to more accurately normalize the three dimensional location of DBS targets by accounting for variability among patients in brain anatomy and dimensions. The points representing the optimal location for stimulation were then projected onto the AtlasePD, forming a cluster. Finally, this data was compared to lead placement in 40 PD patients with advanced disease who underwent an identical surgical procedure for the placement of DBS electrodes into the STN at Vanderbilt using the same MRI atlas normalization methodology.

RESULTS

Perioperative Adverse Events

Table 1 summarizes the adverse events reported for the 15 patients randomized to surgical treatment in this study. Additionally, Table 2 lists adverse events noted in the literature over the past 5 years for STN-DBS surgeries performed in advanced PD patients. Fourteen of the 15 patients did not sustain any long-term (>3 months) complications from the surgery. Short-term, transient complications included headache, confusion, balance difficulty, dysarthria, mild weakness or syncope in 12 patients. One subject suffered a perioperative stroke resulting in persistent mild cognitive changes and slight right arm and face weakness. Overall, the rate of complications experienced by this small group of patients is similar to the rate of complications experienced by patients undergoing STN-DBS with advanced PD (Table 2). However, our sample size is too small to make a statistical comparison.

Table 1.

All perioperative adverse events experienced by this group of 15 patients who received bilateral STN-DBS with early stage of Parkinson’s disease.

| Type of Adverse Event | Transient | Ongoing |

|---|---|---|

| Related to Procedure or Device | ||

| Aborted procedures | 2 | N/A |

| Wound healing problems | 9 | 1 |

| Erythema | 2 | 0 |

| Edema | 2 | 0 |

| Pain | 2 | 0 |

| Drainage | 2 | 0 |

| Tingling | 0 | 1 |

| Tenderness | 1 | 0 |

| Headache | 5 | 0 |

| Edema | 4 | 0 |

| Scalp | 2 | 0 |

| Facial | 2 | 0 |

| Confusion | 4 | 0 |

| Imbalance | 3 | 0 |

| Drowsiness | 2 | 0 |

| Nausea | 2 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0 |

| Speech difficulty | 2 | 0 |

| Neck problems | 2 | 0 |

| Pain | 1 | 0 |

| Stiffness | 1 | 0 |

| Throat problems | 2 | 0 |

| Pain | 1 | 0 |

| Edema | 1 | 0 |

| Hematoma | 1 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 1 | 0 |

| Intracranial edema | 1 | 0 |

| Basal ganglia infarct | 0 | 1 |

| Extremity weakness | 0 | 1 |

| Hallucination | 1 | 0 |

| Urinary retention | 1 | 0 |

| Related to Study | ||

| Syncope | 1 | 0 |

| Not Related to Study | ||

| Incidental sinus abnormalities identified on CT | 0 | 4 |

| Paresthesias | 1 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 | 0 |

| Chest soreness | 1 | 0 |

Table 2.

Comparison of the incidence of adverse events from STN-DBS lead implantation in this study versus complications reported in other studies of STN-DBS for advanced PD.

| Advanced Parkinson’s disease | Early PD |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyons et al. 2004 [20] |

Hariz et al. 2008 [21] |

Tir et al. 2007 [22] |

Seijo et al. 2007 [23] |

Schupbach et al. 2005 [24] |

Gervais-Bernard et al. 2009 [25] |

Gill et al. 2007 [26] |

||

| Patients (n) | 81 | 49 | 100 | 130 | 37 | 42 | 72 | 15 |

| Follow up (years) | 1 – 4.5 | 4 | 1 | 0.3 – 7.75 | 5 | 5 | 2 (average) | 2 |

| Complication | Percent (and total number) of patients experiencing each complication | |||||||

| Confusion | 6.2% (8) | 16% (6) | 27% (4) | |||||

| Balance difficulty | 12.5% (8) | 20% (3) | ||||||

| Speech difficulty | 14.1% (9) | 13% (2) | ||||||

| Weakness | 3.1% (2) | 7% (1) | ||||||

| Aborted procedure | 4.9% (4) | 10.7% (14) | 13% (2) | |||||

| Urinary retention | 5% (2) | 7% (1) | ||||||

| Misplaced leads | 12.5% (10) | 8% (8) | 3.8% (5) | 8% (3) | 0 | |||

| Intracranial bleed | 1.2% (1) | 6% (6) | 6.9% (9) | 5% (2) | 12.5% (9) (asymptomatic) | 0 | ||

| Seizures | 1.2% (1) | 10% (13) | 0 | |||||

| Infection | 6.2% (5) | 7% (7) | 3% (1) | 7% (3) | 9.7% (7) | 0 | ||

| Hypomania | 8% (3) | 0 | ||||||

| Lower limb phlebitis | 5% (2) | 0 | ||||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 2% (1) | 0 | ||||||

Lead Placement

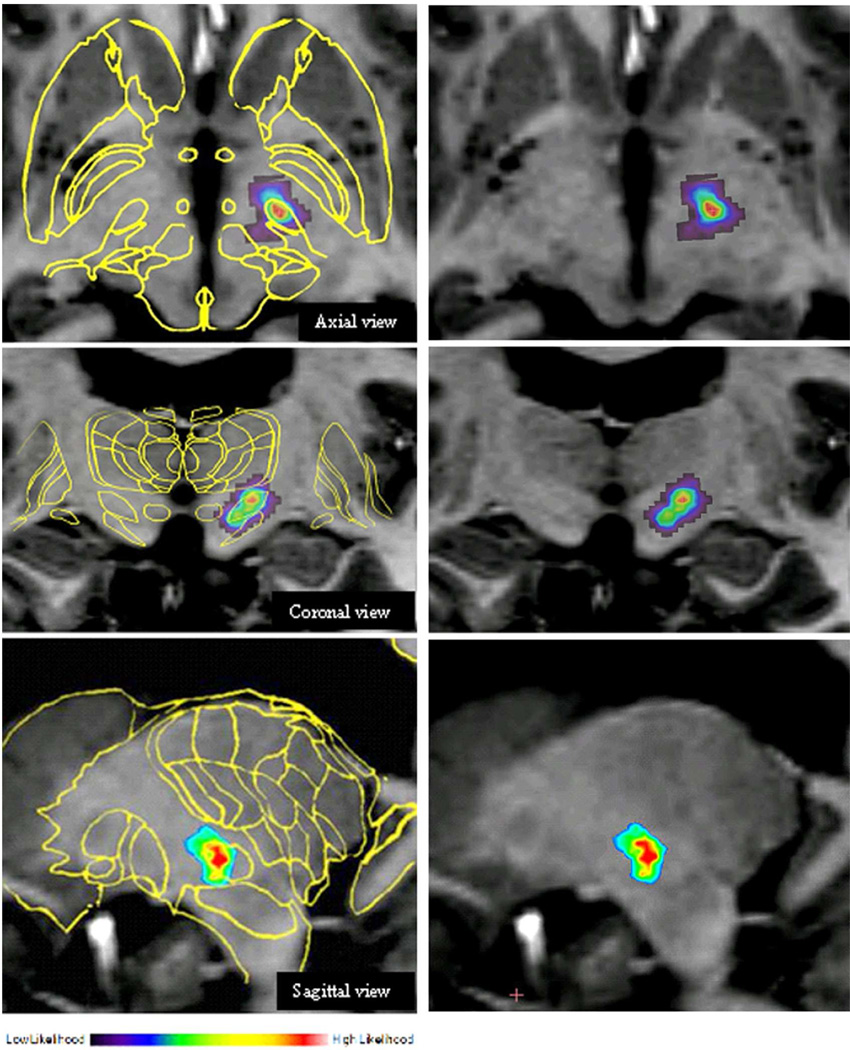

Figure 1 illustrates the normalized position of the active contact projected onto the reference MRI volume overlaid with the Schaltenbrand-Wahren AtlasePD. The average optimal position for the therapeutic contact in the early PD population patients was: lateral 10.7±1.7mm, anterior −1.1±1.7mm, superior −3.3±2.5mm (relative to the mid-commissural point), as indicated in Table 3. This location is 0.77mm distant in a vector directed slightly more medial than the optimal contact used for treatment of 47 advanced PD patients by the same surgeon (lateral 11.4±1.5mm, anterior −1.0±1.7mm, superior −2.7±1.7mm). However, this distance is not statistically different (p > 0.05). Based on coregistration of the DBS lead with the MRI in these early PD patients, optimal therapeutic contact position is likely in the dorso-lateral region of the STN.

Figure 1.

Location of DBS lead placement in all ePD patients projected onto normalized axial, coronal, and sagittal MRIs. Statistical confidence in color, with red representing highest probability of efficacious lead placement. A 2D-scaled slice of the basal ganglia and surrounding structures from the Schaltenbrand-Wharen Atlas is superimposed on the MRI images to the left.

Table 3.

A comparison of normalized AC-PC coordinates of the optimal therapeutic contact (geometric center) in early versus late PD patients undergoing bilateral STN implants by the same surgical team. All values are in millimeters and relative to the midpoint between the anterior and posterior commissures. Methods of non-rigid normalization and extraction of the contact locations are detailed in D’Haese et al.[11]

| Patients | Implanted Leads |

Position of Active Contact | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Lateral | Superior | ||||

| Early PD | N=15 | N=30 | Avg. | −1.1 | 10.7 | −3.3 |

| St. Dev. | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.5 | |||

| Late PD | N=47 | N=94 | Avg. | −1.0 | 11.4 | −2.7 |

| 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | ||||

DISCUSSION

Adverse events

The most serious adverse event experienced by this cohort of patients was a mild, non-hemorrhagic stroke resulting in mild cognitive changes and mild right upper extremity paresis. The presence of cognitive impairment in STN-DBS series ranged from 6.2% (n=130) to 16% (n=37) in recent larger series.[23,24] However, these series did not report the incidence of procedural related stroke as a cause for cognitive impairment, which was the case in our small series. In addition to cognitive impairment, our patient also had a mild contralateral facial and upper extremity weakness that was still present at two years post-surgery. Although this report reflects the occurrence of a non-hemorrhagic stroke that occurred in one of the 15 surgical patients at our institution (6.7%), we reported that the stroke rate in a larger series of patients undergoing bilateral DBS implantation for advanced Parkinson’s disease at our institution was 1.4% for permanent neurological deficit (1/72 patients) and 6.4% for transient neurological deficits (5/72 patients).[26] In another larger series, reported by Hariz et al in 2008, the occurrence of hemiparesis was 3.1% (n=49).[27] Since there was no intracerebral hemorrhage noted on immediate post-operative CT, it is plausible that a small embolus may have occurred in the peri-operative period as a result of this procedure or coincident with this procedure.

The only other persistent adverse event related to STN-DBS in our series is the presence of sensory changes in the scalp experienced by one patient. This was located near the parietal incision for the connector lead, but was not painful, nor did it require medications for treatment. One subject experienced a brief episode of syncope intraoperatively during the procedure for electrode implantation, likely due to sensitivity to the sedative. Once it resolved, the surgical procedure was successfully completed.

Two procedures were electively aborted (13%) in our series, which compares to 4.9% (n=81) and 10.7% (n=130) reported by Lyons et al [20] and Seijo et al [23] respectively. In our two patients, the reason was due in one case to possible contamination of surgical instruments and frame after skin incision was made, and the other due to failure to identify a satisfactory target based on microelectrode recording and intraoperative stimulation. In both cases, subjects subsequently returned to the operating room within three weeks and were successfully implanted. While the first incident is not unique to DBS surgery, the second one is. Our final target location is based on agreement among the surgeon, neurologist and neurophysiologist as to reasonable concordance of the data. In this case, semi-micro test stimulation did not provide somatic, motor or sensory paresthesias, or occulomotor findings in the surrounding regions where MER data defined the boundary of STN. Furthermore, there was no obvious symptom reduction during the first surgery. This may have been due to an unappreciated technical failure in the recording and/or stimulation equipment. In both cases, we were able to return within a few weeks and resume the procedure with successful identification of the final target location.

Speech difficulty in the post-operative period was noted in two patients. This resolved after two days in one patient and after three months in the other. Hariz et al also noted a 14% incidence of “speech difficulties/dysphonia/dysarthria” following STN-DBS surgery.[21] The reversible nature of this post-operative change suggests that it was related to a micro-lesioning effect or edema in the region of the electrode, since no hemorrhage on CT was noted in these two patients.

We are pleased that no intracranial hemorrhages were reported in these 15 patients, despite using multi-electrode MER passes in all cases. The use of multi-electrode, simultaneous MER recordings has several advantages; namely, it is a more efficient way of mapping multiple points along a general trajectory, it avoids brain shift that may happen with tandem MER recordings, and it provides opportunity for more data points to be collected simultaneously prior to a micro-lesioning effect. Furthermore, the use of a bilateral, rapid prototyped fixture (microTargeting® platform) allows us to analyze asymmetries in the electrophysiology of basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease by recording from both sides simultaneously in a given patient.

Lead position

Both the final intraoperative target and the optimal programmed contact position in this cohort of patients falls superior and lateral to the point where STN is largest on the Schaltenbrand-Wahren atlas (12 mm lateral, −2 mm anterior and 5 mm inferior relative to the mid-commissural point).[28] Our final intraoperative target, determined by optimal MER activity and response to intraoperative semi-microstimulation, is similar to the optimal target for STN described by Starr.[29] The final programmed contact in our series was also similar to the final contact position reported by Richardson et al, who revised STN-DBS leads in 8 patients with suboptimal response to for PD, and observed that the effective contact was located in the dorsolateral location of STN (anterior −1.2, lateral 11.4, and superior −2.1; mean AC-PC coordinates in mm).[30] The position of the active contact in Richardson’s series was defined as the center of the contact artifact seen on postoperative MRI. In our series, we use a lead extrapolation algorithm based on coregistration of the contacts seen on post-implant CT imaging with the preoperative MRI [31] which resulted in nearly in the same AC-PC location for our contact when compared to Richardson’s series.

We also found that the actual position of the active contact was on average only 1.5mm (s.d. 0.9mm) more inferior to the intraoperative final target. This suggests that our methods of preoperative anatomical targeting and intraoperative localization can effectively define a therapeutic target in early PD. This was not obvious at the outset of the trial due to concerns that MER data and intraoperative stimulation in early PD may not adequately define a therapeutic zone. These data support the notion that placement of the DBS lead in early PD can be performed similarly to the procedure for advanced PD, even in the presence of few symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

STN-DBS is well established as a safe and effective treatment for advanced PD.[1,32] The perioperative adverse events in this trial of subjects with early stage PD are comparable to that reported for DBS in advanced PD.

The optimal therapeutic contact position for STN-DBS in subjects with early PD enrolled in this trial is not significantly different from that in late stage disease. This finding is encouraging and supports two important conclusions. First, it suggests that the physiological mechanism for effective symptom relief with STN-DBS is similar in early and advanced PD. Second, it suggests that, if patients undergo DBS early in their disease course, they likely will not routinely require revision surgery as the disease progresses. Had the optimal lead position been different between early and advanced disease, one might conclude that a given patient would require two surgeries for optimal symptom relief: one at an early stage, followed by a revision at an advanced stage aimed at a different target within the STN.

Important data regarding the long-term safety, tolerability and efficacy of STN-DBS in early PD will come from this and future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported the Vanderbilt CTSA grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH, Medtronic, Inc., NIH-NIBIB 1 R01-EB006136, and by gifts from private donors.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: Vanderbilt University has received income from grants and contracts with Allergan and Medtronic for research led by Dr. Charles. Dr. Charles has received income from Allergan and Medtronic for education and consulting services. Dr. Konrad has received income from grants and contracts with Medtronic Neurological Inc and FHC Inc for research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krack P, Batir A, Van Blercom N, et al. Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1925–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temel Y, Kessels A, Tan S, et al. Behavioural changes after bilateral subthalamic stimulation in advanced parkinson disease: A systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2006;12:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace BA, Ashkan K, Heise CE, et al. Survival of midbrain dopaminergic cells after lesion or deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in mptp-treated monkeys. Brain. 2007;130:2129–2145. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spieles-Engemann AL, Behbehani MM, Collier TJ, et al. Stimulation of the rat subthalamic nucleus is neuroprotective following significant nigral dopamine neuron loss. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visser-Vandewalle V, van der Linden C, Temel Y, et al. Long-term effects of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in advanced parkinson disease: A four year follow-up study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilker R, Portman AT, Voges J, et al. Disease progression continues in patients with advanced parkinson's disease and effective subthalamic nucleus stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1217–1221. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.057893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles PD, Gill CE, Davis TL, et al. Is deep brain stimulation neuroprotective if applied early in the course of pd? Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:424–426. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konrad PE, Neimat JS, Yu H, et al. Customized, miniature rapid-prototyped stereotactic frames for use in deep brain stimulator surgery: Initial clinical methodology and experience from 263 patients from 2002 – 2008. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2011;89:34–41. doi: 10.1159/000322276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzpatrick JM, Konrad PE, Nickele C, et al. Accuracy of customized miniature stereotactic platforms. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2005;83:25–31. doi: 10.1159/000085023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade-Souza YM, Schwalb JM, Hamani C, et al. Comparison of 2-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging and 3-planar reconstruction methods for targeting the subthalamic nucleus in parkinson disease. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.05.033. discussion 362-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Haese PF, Pallavaram S, Li R, et al. Cranialvault and its crave tools: A clinical computer assistance system for deep brain stimulation (dbs) therapy. Med Image Anal. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross RE, Krack P, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, et al. Electrophysiological mapping for the implantation of deep brain stimulators for parkinson's disease and tremor. Mov Disord. 2006;21(Suppl 14):S259–S283. doi: 10.1002/mds.20960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benazzouz A, Breit S, Koudsie A, et al. Intraoperative microrecordings of the subthalamic nucleus in parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S145–S149. doi: 10.1002/mds.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchison WD, Allan RJ, Opitz H, et al. Neurophysiological identification of the subthalamic nucleus in surgery for parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:622–628. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magarinos-Ascone CM, Figueiras-Mendez R, Riva-Meana C, et al. Subthalamic neuron activity related to tremor and movement in parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2597–2607. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnin M, Morel A, Jeanmonod D. Single-unit analysis of the pallidum, thalamus and subthalamic nucleus in parkinsonian patients. Neuroscience. 2000;96:549–564. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Rodriguez M, Guridi J, et al. The subthalamic nucleus in parkinson's disease: Somatotopic organization and physiological characteristics. Brain. 2001;124:1777–1790. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.9.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pallavaram S, D'Haese PF, Kao C, et al. A new method for creating electrophysiological maps for dbs surgery and their application to surgical guidance. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2008;11:670–677. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-85988-8_80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohde GK, Aldroubi A, Dawant BM. The adaptive bases algorithm for intensity-based nonrigid image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2003;22:1470–1479. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.819299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyons KE, Wilkinson SB, Overman J, et al. Surgical and hardware complications of subthalamic stimulation: A series of 160 procedures. Neurology. 2004;63:612–616. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134650.91974.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hariz MI, Rehncrona S, Quinn NP, et al. Multicenter study on deep brain stimulation in parkinson's disease: An independent assessment of reported adverse events at 4 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23:416–421. doi: 10.1002/mds.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tir M, Devos D, Blond S, et al. Exhaustive, one-year follow-up of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in a large, single-center cohort of parkinsonian patients. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:297–304. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000285347.50028.B9. discussion 304-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seijo FJ, Alvarez-Vega MA, Gutierrez JC, et al. Complications in subthalamic nucleus stimulation surgery for treatment of parkinson's disease. Review of 272 procedures. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2007;149:867–875. doi: 10.1007/s00701-007-1267-1. discussion 876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schupbach WM, Chastan N, Welter ML, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in parkinson's disease: A 5 year follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1640–1644. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.063206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gervais-Bernard H, Xie-Brustolin J, Mertens P, et al. Bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in advanced parkinson's disease: Five year follow-up. J Neurol. 2009;256:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill CE, Konrad PE, Davis TL, et al. Deep brain stimulation for parkinson's disease: The Vanderbilt University medical center experience, 1998–2004. Tenn Med. 2007;100:45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hariz GM, Blomstedt P, Koskinen LO. Long-term effect of deep brain stimulation for essential tremor on activities of daily living and health-related quality of life. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon MS, Munz M. Placement of deep brain stimulators into the subthalamic nucleus. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1999;72:145–149. doi: 10.1159/000029717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Starr PA. Placement of deep brain stimulators into the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus internus: Technical approach. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79:118–145. doi: 10.1159/000070828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson RM, Ostrem JL, Starr PA. Surgical repositioning of misplaced subthalamic electrodes in parkinson's disease: Location of effective and ineffective leads. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87:297–303. doi: 10.1159/000230692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Haese PF, Pallavaram S, Konrad PE, et al. Clinical accuracy of a customized stereotactic platform for deep brain stimulation after accounting for brain shift. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2010;88:81–87. doi: 10.1159/000271823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar R, Lozano AM, Kim YJ, et al. Double-blind evaluation of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in advanced parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1998;51:850–855. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]