Abstract

Since the performance of surgical procedures of the axilla in the treatment of early breast cancer is decreasing, the role of axillary ultrasound (AUS) as staging procedere has newly to be addressed. The aim of this study was to determine which patient or histopathological characteristics are related to false-negative AUS. In a retrospective study design data of 470 women with primary breast cancer were collected from patient charts and imaging and pathology records were reviewed. True positive and false negative axillary ultrasound groups were compared in terms of tumor size, histological subtype, grade, estrogen receptor (ER) and HER2 status, proliferation index, number and size of nodal metastases, extracapsular extension (ECE) and lymphovascular invasion (LVI). Of 470 patients, 166 (35%) were node positive, 79 of them with suspicious AUS. Factors associated with false negative AUS by univariate analysis were included in a multivariate model. By multivariate analysis, only size of nodal metastases was an independent factor for false negative AUS. In the sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) subgroup, 45% of patients had nodal metastasis size less than or equal to 5 mm. In conclusion, AUS in preoperative staging of early stage breast cancer is limited by small size of metastases in a substantial number of patients. Prospective studies have to show whether small metastatic deposits leaving in patients in case of no axillary surgery have no negative effect on disease free and overall survival.

Introduction

During the last decades, axillary lymph node metastases have been one of the most important prognostic parameters in patients with breast cancer. Today, in clinically negative axilla surgical (cN0) staging with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) represents the standard of care. However, more than 60% of all primary breast cancers do not have lymph node metastases. Due to the introduction of national screening programs a greater proportion of breast cancers are detected in an early stage with an increasing number of nodal negative disease. For these patients, even SLNB represents an overtreatment and may not be indicated. For many solid tumours the role of lymph node dissection is yet controversial, since it does not influence mortality. It is commonly acknowledged that the risk of developing metastases depends mainly on the biological behavior of the primary (seed and soil theory) (Engel et al. 2006). Moreover, a series of carefully performed prospective randomized trial focusing on axillary surgery in breast cancer exist showing a high rate of locoregional control achieved with multimodality therapy, even without axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) (Fisher et al. 2002; Group et al. 2006; Martelli et al. 2005; Giuliano et al. 2011). In fact, with the increasing influence of breast cancer biology on adjuvant treatment decisions, the relevance of nodal status is decreasing. It arises the question whether the information is necessary which we gain from identifying and examining the sentinel node (Gerber et al. 2011). Two planned prospective trials are focussing on this topic: SOUND (Sentinel Node vs. Observation after axillary Ultrasound) and German/Austrian INSEMA-Trial, an Intergroup study to compare axillary SLNB vs. no axillary surgery in patients with early primary breast cancer (Gentilini & Veronesi 2012). In this context, the role of preoperative axillary ultrasound (AUS) as a staging procedere has newly to be addressed. There is no doubt, that AUS, carried out by an experienced examiner, provides valuable information in the diagnosis of axillary metastatic involvement. But there are no standards defining sonographically suspicious lymph nodes. In a systematic review including 16 studies using morphologic criteria for positivity, sensitivity ranged from 26.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] 15.3-40.3%) to 75.9% (56.4-89.7%), and specifity varied between 88.4% (82.1-93.1%) and 98.1% (90.1-99.9%). Combining AUS with sonographically guided fine-needle aspiration (AUS-FNA), sensitivity varied between 30.6% (22.5-39.6%) and 62.9% (49.7-74.8%) and specificity reached nearly 100% (94.8-100%) (Alvarez et al. 2006). A recent meta-analysis from Houssami et al. including 31 studies focusing on ultrasound guided core needle biopsy (UNB) in preoperative breast cancer staging showed an estimated sensitivity of 79.6% (74.1-84.2%) and specificity of 98.3% (97.2-99.2%). Subgroup analysis revealed that UNB provided more utility in women with average or higher underlying higher risk for node metastases (Houssami et al. 2011).

However, the aim of most recent studies dealing with AUS in breast cancer was to identify women with lymph node metastases (imaging N1[iN1]) to spare SLNB and refer them directly to ALND. In view of the potentially avoidance of axillary surgery in future, the aim of our study (primary objective) was to identify factors influencing accuracy of AUS in preoperative breast cancer assessment. For that reason, we analyzed the sonographically missing metastatic lymph nodes (false negatives) at our institution. Secondary, we determined patients at risk for nodal involvement using tumour biological parameters as well as nomograms.

Materials and methods

A total of 470 patients with primary breast cancer referred to our university hospital between February 2008 and January 2010 were enrolled in this retrospective study. In concordance to the institutional policy breast ultrasound including AUS was carried out by one of five experienced examiners before core needle biopsy. Lymph nodes were identified as abnormal according to sonographic criteria including absence of a fatty nodal hilum or a round hypoechoic node. Patients with sonographically negative nodes were subjected to SLNB. Patients with sonographically positive lymph nodes or contraindications for SLNB underwent ALND. Secondary, completion ALND was carried out in patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes. Patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded from this analysis. The institutional review board approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patient charts were reviewed for patient demographics, primary tumour histology, tumour size, grade, hormone receptor status, HER2 status, results of AUS, number of sentinel lymph nodes (removed and involved), number of lymph nodes after ALND, number of positive nodes by histological examination, presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) or extracapsular extension (ECE). For determination of the size of the largest metastatic deposit of involved lymph nodes histological H&E slides were reviewed by our pathologist.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS 19.0 software package (IBM Ehningen, Germany). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of AUS in the detection of lymph node metastases were calculated. To compare the proportion of missed axillary metastases between subgroups, Fisher’s exact (two variables), Pearson chi-square (three or more nominal variables or linear-by-linear association tests (three or more ordered variables) were used. The variables that were significant by univariate analysis were tested by multivariate logistic regression, to assess which of them had independent significance. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided. Clinical data were incorporated into the nomogram of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer center (MSKCC) to predict probability of SLN metastases (Bevilacqua et al. 2007). Discrimination of MSKCC nomogram was analyzed using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Results

Lymph node metastases and primary tumour pathology

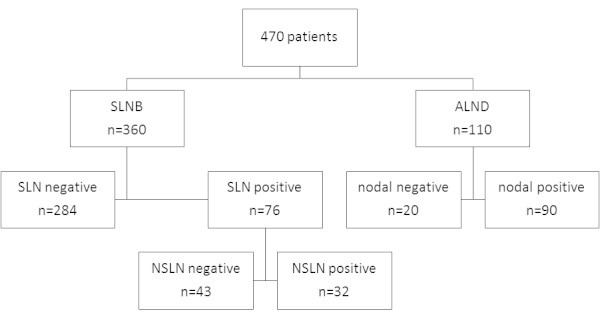

From 470 patients with primary breast cancer, 166 patients (35.3%) had lymph node metastases. Baseline characteristics in relation to lymph node status are presented in Table 1. Concerning the surgical approach, 110 patients were primary treated with ALND. In 92 of them AUS was positive and 18 patients had contraindications for SLNB (large tumour size, previous extensive breast surgery). The remaining 360 patients underwent SLNB, 76 of them (21.1%) had metastatic involved lymph nodes. In 75 patients with pN + (sn) completion ALND was performed with the result of 32 patients having positive non-SLN (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 470)

| Patients | pN+ | % | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | n.s. | |||

| ≤50 | 74 | 28 | 37.8 | |

| >50 | 396 | 138 | 34.8 | |

| BMI | n.s. | |||

| <25 | 180 | 60 | 33.3 | |

| 25-29.9 | 165 | 59 | 35.8 | |

| ≥30 | 124 | 46 | 37.1 | |

| Tumour stage | <0.001 | |||

| pT1 | 278 | 62 | 22.3 | |

| pT2 | 164 | 81 | 49.4 | |

| pT3 & pT4 | 28 | 23 | 82.1 | |

| Histological subtype | 0.045 | |||

| Ductal | 340 | 128 | 37.6 | |

| Lobular | 44 | 16 | 36.4 | |

| Others | 86 | 22 | 25.6 | |

| Grading | <0.001 | |||

| G1 | 67 | 6 | 9 | |

| G2 | 261 | 88 | 33.7 | |

| G3 | 142 | 72 | 50.7 | |

| Lymphangiosis | <0.001 | |||

| No | 278 | 33 | 11.9 | |

| Yes | 192 | 133 | 69.3 | |

| Growth pattern | <0.001 | |||

| Unifocal | 427 | 139 | 32.6 | |

| Multicentric | 40 | 25 | 62.5 | |

| ER status | n.s. | |||

| Positive | 383 | 129 | 33.7 | |

| Negative | 87 | 37 | 42.5 | |

| PR status | 0.024 | |||

| Positive | 339 | 109 | 32.2 | |

| Negative | 131 | 57 | 43.5 | |

| HER2 status | n.s. | |||

| Negative | 432 | 150 | 34.7 | |

| Positive | 38 | 16 | 42.1 | |

| Ki-67 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤14% | 161 | 38 | 23.6 | |

| >14% | 282 | 122 | 43.3 | |

| Total | 470 | 166 | 35.3 |

Figure 1.

Flow chart of involvement of axillary lymph nodes (n = 470).ALND axillary lymph node dissection, SLNB sentinel lymph node biopsy, SLN sentinel lymph node, NSLN nonsentinel lymph node.

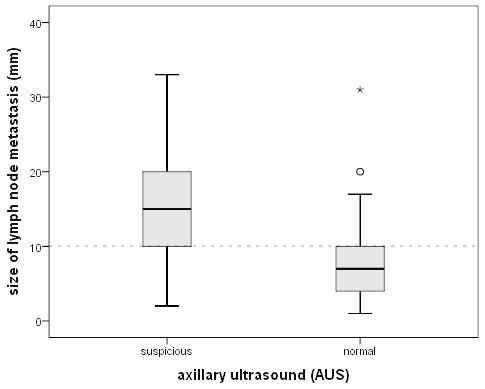

Axillary US was abnormal in 79 patients with metastatic lymph nodes and in 13 patients without nodal involvement. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of axillary US were 47.6%, 95.7%, 85.9%, 77% and 78.7%, respectively (Table 2). The proportion of sonographically missed axillary metastases was significant lower in large-sized tumours, grade 3 tumours, presence of lymphangiosis, ER/PR negative tumours, HER2-positive tumours and Ki-67 > 14% (Table 3) as well as nodal metastasis size >5 mm, N2- or N3-disease and extracapsular extension (Table 4). No differences in the false-negative AUS findings were seen according to age, BMI, histological subtype and multifocal/multicentric disease. To evaluate which of the parameters had independent prognostic value in the prediction of false-negative AUS, the factors that were significant by univariate analysis were tested in a multivariate model. By multivariate logistic regression, pathological size of nodal metastases was the only significant parameter associated with false negative ultrasound findings (Table 5). According to the study group, from 166 patients with nodal involvement, lymph node metastasis size was available in 163 patients. As shown in Table 4, 41 patients (25.2%) had metastases ≤5 mm, which were detected with AUS in only in 4 cases (9.8%). In contrast, from 76 (45.8%) patients with lymph node metastases >10 mm, 55 (72.4%) were identified by ultrasound (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of axillary lymph node status as assessed with pathology and axillary ultrasound

| Axillary ultrasound | SLNB/ALND | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 79 | 13 | 92 |

| Negative | 87 | 291 | 378 |

| Total | 166 | 304 | 470 |

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of axillary ultrasound in the detection of lymph node metastases: 47.6% (95%CI 40.1; 55.2), 95.7% (92.8; 97.5); 85.9% (77.3; 91.6); 77% (72.5; 80.9) and 78.7% (74.5; 82.9). SLNB Sentinel lymph node biopsy, ALND Axillary lymph node dissection, CI Confidence interval.

Table 3.

False-negative rate of axillary ultrasound (AUS) in different subgroups of 166 nodal-positive patients

| pN+ | AUS positive | AUS negative | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | |||

| Age (years) | n.s. | ||||

| ≤50 | 28 | 16 | 12 | 42.9 | |

| >50 | 138 | 63 | 75 | 54.3 | |

| BMI | n.s. | ||||

| <25 | 60 | 28 | 32 | 53.3 | |

| 25-29.9 | 59 | 24 | 35 | 59.3 | |

| ≥30 | 46 | 26 | 20 | 43.5 | |

| Tumour stage | 0.001 | ||||

| pT1 | 62 | 20 | 42 | 67.7 | |

| pT2 | 81 | 42 | 39 | 48.1 | |

| pT3 & pT4 | 23 | 17 | 6 | 26.1 | |

| Histological subtype | n.s. | ||||

| Ductal | 128 | 66 | 62 | 48.4 | |

| Lobular | 16 | 5 | 11 | 68.8 | |

| Others | 22 | 8 | 14 | 63.6 | |

| Grading | 0.005 | ||||

| G1 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 83.3 | |

| G2 | 88 | 34 | 54 | 61.4 | |

| G3 | 72 | 44 | 28 | 38.9 | |

| Lymphangiosis | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 33 | 7 | 26 | 78.8 | |

| Yes | 133 | 72 | 61 | 45.9 | |

| Growth pattern | n.s. | ||||

| Unifocal | 139 | 65 | 74 | 53.2 | |

| Multicentric | 25 | 14 | 11 | 44.0 | |

| ER status | 0.024 | ||||

| Positive | 129 | 55 | 74 | 57.4 | |

| Negative | 37 | 24 | 13 | 35.1 | |

| PR status | 0.014 | ||||

| Positive | 109 | 44 | 65 | 59.6 | |

| Negative | 57 | 35 | 22 | 38.6 | |

| HER2 status | 0.007 | ||||

| Negative | 150 | 66 | 84 | 56 | |

| Positive | 16 | 13 | 3 | 18.8 | |

| Ki-67 | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤14% | 38 | 9 | 29 | 76.3 | |

| >14% | 122 | 69 | 53 | 43.4 | |

| Total | 166 | 79 | 87 | 52.4 | |

n.s. = not significant.

Table 4.

False-negative rate of axillary ultrasound (AUS) depending on extension of nodal involvement (n = 166)

| nodal-positive | AUS positive | AUS negative | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | % | ||

| Nodal metastasis size * | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤5 mm | 41 | 4 | 37 | 90.2 | |

| 5.1-10 mm | 46 | 19 | 27 | 58.7 | |

| >10 mm | 76 | 55 | 21 | 27.6 | |

| Number of metastatic involved lymph nodes | <0.001 | ||||

| N1 (1–3) | 86 | 27 | 59 | 68.6 | |

| N2 (4–9) | 48 | 28 | 20 | 41.7 | |

| N3 (≥10) | 32 | 24 | 8 | 25.0 | |

| Capsular infiltration | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 83 | 23 | 60 | 72.3 | |

| Yes | 83 | 56 | 27 | 32.5 | |

* 3 missing value.

Table 5.

Significant predictors of false-negative axillary ultrasound (false-negative ratio = OR) in 470 patients with breast cancer according to univariate and multivariate logistic regression

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Tumour stage | |||

| T1 | 0,004 | 1.55 (1.17-2.04) | n.s. |

| T2-4 | 1 | ||

| Grading | |||

| G1/2 | 0.003 | 1.61 (1.16-2.24) | n.s. |

| G3 | 1 | ||

| Lymphangiosis | |||

| No | 0.001 | 1.72 (1.33-2.22) | n.s. |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| ER status | |||

| Positive | 0.024 | 1.63 (1.03-2.59) | n.s. |

| Negative | 1 | ||

| PR status | |||

| Positive | 0.014 | 1.54 (1.08-2.22) | n.s. |

| Negative | 1 | ||

| HER2 status | |||

| Negative | 0.007 | 2.99 (1.067-8.36) | n.s. |

| Positive | 1 | ||

| Ki-67 | |||

| ≤14% | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.34-2.30) | n.s. |

| >14% | 1 | ||

| Size of nodal metastasis | |||

| ≤10 mm | <0.001 | 2.66 (1.81-3.91) | 0,001 |

| >10 mm | 1 | ||

| Nodal stage | |||

| N1 | <0.001 | 1.96 (1.41-2.73) | n.s. |

| N2-3 | 1 | ||

| Capsular infiltration | |||

| No | <0.001 | 2.22 (1.59-3.11) | n.s. |

| Yes | 1 | ||

OR = Odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; n.s. = not significant.

Figure 2.

Boxplot graph illustrating the difference in nodal metastasis size (mm) in all patients with suspicious (TP = true-positive) and normal axillary ultrasound (FN = false-negative). In the TP group mean metastasis size is 15.5 mm (SD 6.80) in comparison to a mean size of 7.7 mm (SD 5.2) in the FN group mean (p < 0.001). At a cut-off of 10 mm metastasis size, approximately 75% of patients with lymph node metastasis ≥10 mm are detected with AUS, whereas 75% of patients with metastases <10 mm had normal AUS findings.

Subgroup: patients with SLNB

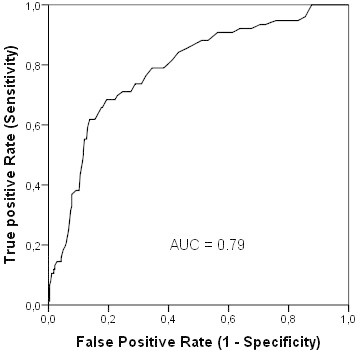

The mean age of the 360 patients operated with SLNB was 63 (range, 29–90) years, and the mean tumour size was 17.6 (range, 1–68) mm. Patients characteristics and tumour pathologic features are presented in Table 6. In total, 76 (21.1%) of 360 patients were identified with pN + (sn) status. Univariate analysis revealed that tumour size (>10 mm), a higher grading, presence of lymphangiosis and multicentric tumour growth were associated with positive nodal disease. In multivariate logistic regression analysis tumour size and multicentric growth were independent parameters related to a positive nodal status (Table 7). Application of the MSKCC nomogram to our sentinel cohort revealed a ROC value of 0.79 (Figure 3).

Table 6.

Patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy (n = 360)

| Patients | pN + (sn) | % | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤50 | 58 | 13 | 22.4 | n.s. |

| >50 | 302 | 63 | 20.9 | |

| BMI | ||||

| <25 | 146 | 31 | 21.2 | n.s. |

| 25-29.9 | 125 | 26 | 20.8 | |

| ≥30 | 89 | 19 | 21.3 | |

| Tumour stage | ||||

| pT1a/b | 64 | 7 | 10.9 | 0.009 |

| pT1c | 182 | 32 | 17.6 | |

| pT2 | 111 | 37 | 33.3 | |

| Histological subtype | ||||

| Ductal | 259 | 57 | 22 | n.s. |

| Lobular | 31 | 8 | 25.8 | |

| Others | 70 | 11 | 15.7 | |

| Grading | ||||

| G1 | 63 | 5 | 7.9 | 0.014 |

| G2 | 211 | 48 | 22.7 | |

| G3 | 86 | 23 | 26.7 | |

| Lymphangiosis | ||||

| No | 250 | 21 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 110 | 55 | 50 | |

| Growth pattern | ||||

| Unifocal | 335 | 65 | 19.4 | 0.021 |

| Multicentric | 22 | 9 | 40.9 | |

| ER status | ||||

| Positive | 301 | 64 | 21.3 | n.s. |

| Negative | 59 | 12 | 20.3 | |

| PR status | ||||

| Positive | 270 | 57 | 21.1 | n.s. |

| Negative | 90 | 19 | 21.1 | |

| HER2 status | ||||

| Negative | 336 | 73 | 21.7 | n.s |

| Positive | 24 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Ki-67 | ||||

| ≤14% | 142 | 24 | 16.9 | 0.067 |

| >14% | 194 | 47 | 24.2 | |

| Total | 360 | 76 | 21.1 |

Table 7.

Predictors of Sentinel Lymph Node metastases in 360 patients with breast cancer according to univariate and multivariate logistic regression

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | p-value | Metastasis rate ratio (95%CI) | p-value |

| Tumour stage | |||

| T1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 0.002 | 2.05 (1.38-3.03) | 0.019 |

| Grading | |||

| G1/2 | 1 | ||

| G3 | 0.014 | 1.38 (0.9-2.11) | n.s. |

| Lymphangiosis* | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 5.95 (3.8-9.33) | |

| Growth pattern | |||

| Unifocal | 1 | ||

| Multicentric | 0.021 | 2.1 (1.22-3.65) | 0.051 |

| Ki-67 | |||

| ≤14% | 1 | ||

| >14% | 0,067 | 2.17 (1.05-4.5) | n.s |

* Multivariate analysis included all preoperatively known parameters with significant results in univariate calculation (excluding lymphangiosis); n.s. = not significant.

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve calculation for the MSKCC nomogram applied to the sentinel cohort of our study population (n = 360). The predictive accuracy of this model, as measured by the area under ROC curve (AUC) was 0.79 (95%CI 0.73; 0.84).

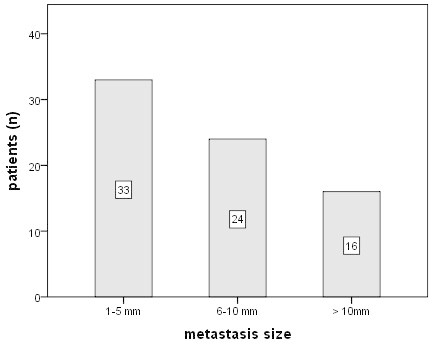

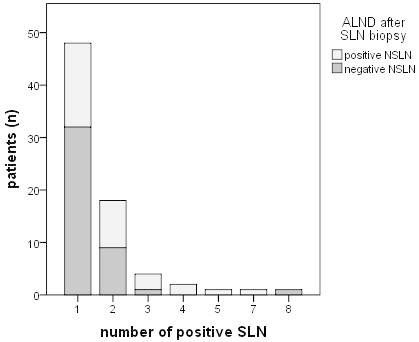

To evaluate the tumour burden of patients with positive SLNB, we analyzed number of positive lymph nodes and size of largest metastastic deposit after completion ALND. Of 76 patients with positive lymph nodes after SLNB, one patient declined further axillary surgery (n = 75). Information about pathological size of lymph node metastases was available in 73 patients. Thirteen (17.8%) patients revealed only micrometastases (pN1mi, ≤ 2 mm), N1 disease (1–3 involved lymph nodes) was present in 55 (72.4%) patients, N2 disease (4–9 metastatic nodes) in 16 (21%) and N3 disease (≥ 10 metastatic nodes) in 5 (6.6%) patients. The mean size of largest metastatic deposit in patients with positive SLN was 7 (range, 1–31, median 6) mm. Metastatic deposits ≤ 5 mm were found in 33 of 73 patients (45%), whereas 16 patients (21.9%) had lymph node metastases > 10 mm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Metastasis size in SLN-positive patients. In 33/73 patients (45.2%) histological metastasis size was maximal 5 mm, 13 of them had micrometastases ≤ 2 mm.

A total of 43 (57.3%) from 75 patients with positive SLN had no further lymph node metastases (NSLN) at the time of completion ALND. In patients with only one positive SLN the rate of positive non-SLN was 33.3% (16/48) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

SLN-positive patients after ALND (n = 75). Involvement of non-SLN (NSLN). 43/75 patients (57.3%) with positive SLN had no further lymph node metastases. In patients with only one positive SLN the rate of positive NSLN is 33.3% (16/48).

Discussion

The role of preoperative AUS in early stage breast cancer is well-examined (Alvarez et al. 2006). However, AUS has a broad range of diagnostic perfomance and the experience of the examiner is crucial for diagnostic precision. The results of our study with sensitivity of 47.6% and specificity of 95.7% confirmed the unsatifactory sensitivity of AUS in axillary staging.

In an attempt to improve the results of AUS, numerous studies have been done dealing with fine needle aspiration (FNA) or core needle biopsy (CNB) of axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. The meta-analysis of Houssami et al. 2397 including sonographically guides biopsies (FNA and CNB) of 4830 patients with a median prevalence of lymph node metastases of 47.2% showed a sensitvity of 75.0% and specificity of 98.5% (Houssami et al. 2011). However, as shown by a raw data analysis of the mentioned studies by Leenders sensitivities ranged from 6 to 63% if all patients were included and not only patients with suspicious AUS followed by FNA or CNB (Leenders et al. 2012). That means that addition of sonographically guided biopsy increases specificity and may help to identify patients with axillary lymph node metastases. But a negative FNA or CNB does not exclude lymph node metastases, since the proportion of false negatives reaches 37.1%.

In our study, the prevalence of lymph node metastases was 35.1% and nodal disease was associated with increasing tumour size, higher grading, presence of lymphangiosis, multicentric disease and high Ki-67 proliferation index. Accuracy of AUS reached 78.7%, but the rate of false negatives was considerable. There was no difference between several examiners (data not shown). Due to clinical experience it seems much more difficult to show lymph nodes sonographically in patients with markedly increased axillary fatty tissue. Unexpectedly, we did not found any difference in the false negatives depending on BMI.

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing the strong association between false negative AUS and size of lymph node metastases. Previous studies only differentiated between micro- and macrometastases and found a higher false negative rate in N1mi stage (Cools-Lartigue et al. 2013). Leenders et al. showed a sensitivity to detect micrometastases of 22.2% in comparison to a sensitivity to detect macrometastases of 51.9% (Leenders et al. 2012). But we must take into account the limits of ultrasound according to lesion size. In our study, 41/163 (25%) patients with N + disease had a maximum size of nodal metastases ≤5 mm. The false-negative rate in this subgroup reached 90%. This can partially be explained by the relatively poor ultrasound criteria defining suspicious lymph nodes used in this study. Other studies have shown a cortical thickness of ≥3 mm to be the most useful predictor of malignancy (Deurloo et al. 2003; Choi et al. 2009; Mainiero et al. 2010). However, the increase of sensitivity is connected with a decrease of specificity, which in clinical practise means that more patients are selected for ALND without having metastatic involved lymph nodes. On the other hands, there remains a considerable number of undetected metastatic involved lymph nodes also in these studies.

We have to ask the question whether other imaging techniques are able to detect small metastatic involved lymph nodes. A comparison between physical examination, mammography, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no advantage of MRI regarding the false negatives (Valente et al. 2012). Mortellaro et al. studied the specific parameters of MRI for axillary staging of breast cancer and found that only the presence of any axillary lymph node without a fatty hilum did correlate with axillary positivity (Mortellaro et al. 2009). With regard to the disadvantages including higher costs and patients physical restrictions there is no role for MRI in the routine use of preoperative axillary staging. The use of 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18 F-FDG-PET) in combination with computed tomography (CT) to determine axillary nodal status is an active area of reserach (Peare et al. 2010). A recent study by Ueda et al. compared the ability of 18FDG-PET/CT with AUS and revealed a similar accuracy of both imaging techniques (Ueda et al. 2008). Actually, the performance of FDG-PET remains to low to replace assessment of axillary status by surgical biopsy and histological examination.

Subgroup of patients with SLNB

Our study revealed metastatic involved SLN in 21.1% of patients, in subgroups of G1 tumours even 7.9% and tumour size ≤ 10 mm 10.8%. Multicentric disease and tumour size were independent risk factors for positive lymph nodes in multivariate analysis. Although SLNB is an extremely safe procedure with low morbidity, it has been suggested that patients with a low risk of axillary lymph node metastases should be spared SLNB (Viale et al. 2005). Concerning the multiparameter approach, Bevilacqua et al. from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) developed a predictive model using nine preoperatively assessable variables associated with SLN metastasis, the so-called MSKCC nomogram. The diagnostic performance of this test was quite accurate with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.75 (Bevilacqua et al. 2007). The evaluation of this model in our study population as well as other cohorts confirmed the good results, but until now SLNB has proven as gold standard in axillary staging (Klar et al. 2009).

In this study cohort, the axillary tumour burden is low with 45.2% of pN + (sn) patients having a maximum size of lymph node metastases ≤ 5 mm and 43.3% having only one metastatic lymph node after completion ALND. Currently, there is an ongoing discussion about the need of completion ALND in pN + (sn) patients. According to the results of the ACOSOG Z0011 [Giuliano] trial, in patients with clinically negative axilla and one or two SLNs containing metastases treated with breast conserving therapy and tangential irradiation completion ALND can be omitted (Giuliano et al. 2011). Recent data of the IBCSG 23–01 trial showed no disadvantage in relapse-free and overall survival in patients with SLN micrometastases omitting completion ALND (Galimberti et al. 2013).

One step more would be to totally give up axillary surgery as staging procedure in clinically and sonographically negative axilla. From well-designed large studies dealing with safety of SLNB it is known that the rate of false negative SLNB is about 7 to 10% (Veronesi et al. 2003; Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Miller BJ, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Mammolito DM, McCready DR, Mamounas EP, Costantino JP, Wolmark N & National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Miller BJ, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Mammolito DM, McCready DR, Mamounas EP, Costantino JP, Wolmark N & National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project ; Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Miller BJ, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Mammolito DM, McCready DR, Mamounas EP, Costantino JP, Wolmark N & National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project 2007). But long time follow-up data of the NSAPB B-32 trial (SLNB + ALND vs. SLNB and ALND only in case of involved SLN) with 3986 patients and a mean follow-up time of 95.6 month have shown that there was no difference in overall survival, disease-free survival and number of recurrences in both study groups. Moreover, the rate of axillary node recurrence was markedly lower than expected. In detail, a total of 8 women with axillary node recurrence was seen in contrast to 57 expected cases of axillary recurrence in the group without ALND (n = 2011) with an underlying incidence of lymph node metastases of 29% and a false negative rate of 9.8% (Krag et al. 2010). Similar results were shown by Veronesi et al. with a cumulative incidence of axillary metastases of 1% at 5 years in 3548 patients with SLNB (Veronesi et al. 2009). However, the 5-year overall survival rate in this series was 98% with a high percentage of pT1 tumors and may not be representative for other studies. It remains the question: Can we accept false negative AUS for nodal metastases ≤10 mm in clinical practice? We know that pN + (sn) patients with low axillary tumour burden do not benefit from extensive axillary surgery in the era of sufficient local (tangential irradiation after BCS) and systemic adjuvant therapy. Moreover, the percentage of pN + patients is decreasing due to mammography screening programs.

Conclusion

This study shows that accuracy of preoperative AUS in early stage breast cancer patients depends mainly on the size of axillary lymph node metastases. Metastatic deposits up to 10 mm represent a substantial number of false negative AUS and remain a diagnostic challenge. Otherwise, adjuvant therapy decisions become more and more independent of nodal involvement and recent studies showed no disadvantage in survival in case of potentially missing metastatic lymph nodes. Future prospective randomized studies including preoperative AUS (SOUND trial, INSEMA trial) will contribute to answer the question if surgical staging of the clinically and sonographically inconspicuous axilla is still necessary in early breast cancer treatment.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors state no conflicts of interest in association with the present manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

AS was responsible for study design, carried out axillary ultrasound and drafted the manuscript. KG collected data and prepared staticical analyses. SH carried out axillary ultrasound examinations. BS was responsible for histopathological examinations. UN carried out statistical analysis concerning the nomogram. MD carried out axillary ultrasound examinations. TR contributed to preparation of the manuscript. BG was the principle investigator and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Angrit Stachs, Email: angrit.stachs@kliniksued-rostock.de.

Katja Göde, Email: kaschnei@med.uni-rostock.de.

Steffi Hartmann, Email: steffi.hartmann@kliniksued-rostock.de.

Bernd Stengel, Email: info@patho-praxis-gue-hro.de.

Ulrike Nierling, Email: ulrike.nierling@kliniksued-rostock.de.

Max Dieterich, Email: max.dieterich@uni-rostock.de.

Toralf Reimer, Email: toralf.reimer@uni-rostock.de.

Bernd Gerber, Email: bernd.gerber@kliniksued-rostock.de.

References

- Alvarez S, Anorbe E, Alcorta P, Lopez F, Alonso I, Cortes J. Role of sonography in the diagnosis of axillary lymph node metastases in breast cancer: a systematic review. AJR. 2006;186:1342–1348. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua JL, Kattan MW, Fey JV, Cody HS, 3rd, Borgen PI, Van Zee KJ. Doctor, what are my chances of having a positive sentinel node? A validated nomogram for risk estimation. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3670–3679. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Ko EY, Han BK, Shin JH, Kang SS, Hahn SY. High resolution ultrasonographic features of axillary lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. Breast. 2009;18:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools-Lartigue J, Sinclair A, Trabulsi N, Meguerditchian A, Nesurolle B, Fuhrer R, Meterissian S. Preoperative axillary ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of axillary metastases in patients with breast cancer: predictors of accuracy and future implications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(3):819–827. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2609-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurloo EE, Tanis PJ, Gilhuijs KG, Muller SH, Kröger R, Peterse JL, Rutgers EJ, Valdés Olmos R, Schultze Kool LJ. Reduction in the number of sentinel lymph node procedures by preoperative ultrasonography of the axilla in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(8):1068–1073. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Lebeau A, Sauer H, Hölzel D. Are we wasting our time with the sentinel technique? Fifteen reasons to stop axilla dissection Breast. 2006;15(3):452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N, et al. (2002) Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):567–575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, Viale G, Luini A, Veronesi P, Baratella P, Chifu C, Sargenti M, Intra M, Gentilini O, Mastropasqua MG, Mazzarol G, Massarut S, Garbay JR, Zgajnar J, Galatius H, Recalcati A, Littlejohn D, Bamert M, Colleoni M, Price KN, Regan MM, Goldhirsch A, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Veronesi U. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with senitnel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23–01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini O, Veronesi U. 2012) Abondong sentinel lymph node biopsy in early breast cancer? A new trial in progress at the European Institute of Oncology of Milan (SOUND: Sentinel node vs. Observation after axillary ultrasound. Breast. 2012;21(5):678–681. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber B, Heintze K, Stubert J, Dieterich M, Hartmann S, Stachs A, Reimer T. Axillary lymph node dissection in early-stage invasive breast cancer: is it still standard today? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(3):613–624. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, Leitch AM, Saha S, McCall LM, Morrow M. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(6):569–575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group IBCS, Rudenstam CM, Zahrieh D, Forbes JF, Crivellari D, Holmberg SB, Rey P, Dent D, Campbell I, Bernhard J, Price KN, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Coates AS. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):337–344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houssami N, Ciatto S, Turner RM, Cody HS, Macaskill P. Preoperative ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of axillary nodes in invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;254:243–251. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821f1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar M, Foeldi M, Markert S, Gitsch G, Stickeler E, Watermann D. Good prediction of the likelihood for sentinel lymph node metastasis by using the MSKCC nomogram in a german breast cancer population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(5):1136–1142. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Miller BJ, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Mammolito DM, McCready DR, Mamounas EP, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(10):881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Costantino JP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Mamounas EP, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Wolmark N. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenders MWH, Broeders M, Croese C, Richir MC, Go HLS, Meijer S, langenhorst BLAM, Schreurs WH. Ultrasound and fine needle aspiration cytology of axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer. To do or not to do? Breast. 2012;21:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero MB, Cinelli CM, Koelliker SL, Graves TA, Chung MA. Axillary ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration in the preoperative evaluation of the breast cancer patient: an algorithm based on tumor size and lymph node appearance. AJR. 2010;195:1261–1267. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli G, Boracchi P, De Palo M, Pilotti S, Oriana S, Zucali R, Daidone MG, De Palo G. A randomized trial comparing axillary dissection to no axillary dissection in older patients with T1N0 breast cancer: results after 5 years of follow-up. Ann Surg. 2005;242(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167759.15670.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortellaro VE, Marshall J, Singer L, Hochwald SN, Chang M, Copeland EM, Grobmyer SR. Magnetic resonance imaging for axillary staging in patients with breast cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(2):309–312. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peare R, Staff RT, Heys SD. The use of FDG-PETin assessing axillary lymph node status in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(1):281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda S, Tsuda H, Asakawa H, Omata J, Fukatsu K, Kondo N, Kondo T, Hama Y, Tamura K, Ishida J, Abe Y, Mochizuki H. Utility of 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT) in combination with ultrasonography for axillary staging in primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente SA, Levine GM, Silverstein MJ, Rayhanabad JA, Weng-Grumley JG, Ji L, Holmes DR, Sposto R, Sener SF. Accuracy of predicting axillary lymph node positivity by physical examination, mammography, ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1825–1830. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, Luini A, Zurrida S, Galimberti V, Intra M, Veronesi P, Robertson C, Maisonneuve P, Renne G, De Cicco C, De Lucia F, Gennari R. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):546–553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi U, Galimberti V, Paganelli G, Maisonneuve P, Viale G, Orecchia R, Luini A, Intra M, Veronesi P, Caldarella P, Renne G, Rotmensz N, Sangalli C, De Brito LL, Tullii M, Zurrida S. Axillary metastases in breast cancer patients with negative sentinel nodes: a follow-up of 3548 cases. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(8):1381–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale G, Zurrida S, Maiorano E, Mazzarol G, Pruneri G, Paganelli G, Maisonneuve P, Veronesi U. Predicting the status of axillary sentinel lymph nodes in 4351 patients with invasive breast carcinoma treated in a single institution. Cancer. 2005;103(3):492–500. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]