Country of birth and length of stay in the United States have proven to be strong predictors of obesity among Mexican-Americans,1 suggesting the U.S. environment may be distinctively “obesogenic.”2 For example, a 12 ounce bottle of American Coca-Cola has 240 calories with 65 grams of sugar, while Mexican Coca-Cola has 150 calories per 12 ounce bottle with 39 grams of sugar (the former is made from high-fructose corn syrup).3,4 However, there is also evidence that immigrants are resistant to these influences: growth in BMI is slower among immigrants than among U.S.-born Mexican-Americans.5 Studies have yet to examine the relationship between migration and obesity in transnational perspective, including comparisons with the Mexican source population to help identify patterns distinctive to the U.S.

Methods

Data from epidemiological surveys in Mexico Mexican National Comorbidity Survey6 (MNCS) and the U.S. Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys7 (CPES) were combined (N=3,244). Obesity was defined as BMI> 30kg/m2 using self-reported height and weight. Respondents with missing weight or height (n=266), implausibly high BMI (>65 kg/m2) (n=3), and current pregnancy (n=62) were excluded. Comparison groups were defined using information on respondents' personal and familial connection to Mexico-U.S. migration. MNCS respondents were divided into 1) Mexicans who have never been to the U.S. and do not have a migrant in their immediate family (living in Mexico, no migrant in family n=1,050); 2) Mexicans who have not been to the U.S. but have a migrant in their immediate family (living in Mexico, migrant in family, n=955); and 3) Mexicans who have previously been migrants in the U.S. (living in Mexico, previous migrant n=126). Respondents in the U.S. were divided into: 1) Mexican-born immigrants (first generation in US, n=509); 2) U.S.-born with one or more Mexican-born parent (second generation in US, n=285); 3) U.S.-born with U.S.-born parents who self-identified as Mexican-American (third generation in US, n=319). Covariates included age (continuous), marital status (married, divorced, never married), educational attainment (0-5, 6-8, 9-11, 12+ years), and current smoking status. Analyzes were conducted using SUDAAN to adjust for the complex survey design.8

Results

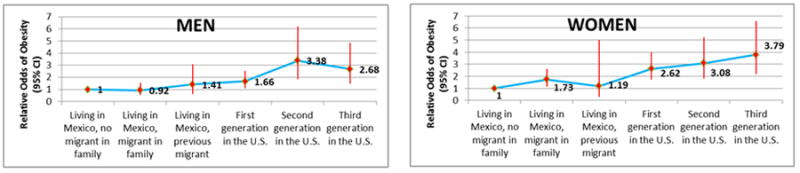

With statistical adjustment for age, marital status, education, and smoking the odds of obesity among men were higher among first generation in US (OR=1.66, 95% CI 1.10-2.52), second generation in US (OR=3.38, 95% CI 1.84-6.20), and third generation in US (OR=2.68, 95% CI 1.48-4.86), relative to men living in Mexico, no migrant in family (Figure 1). Among women the adjusted odds of obesity were higher for the first generation in US (OR=2.62, 95% CI 1.72-4.00), second generation in US (OR=3.08, 95% CI 1.81-5.23), and third generation in US (OR=3.79, 95% CI 2.19-6.57) relative to women living in Mexico with no migrant in family. Among women but not among men, respondents living in Mexico with a family member in the US were more likely to be obese than those with no migrants in their family (OR=1.73, 95% CI 1.14-2.62).

Figure 1. Relative Odds of Obesity Associated with Migration in Mexico and the United States.

Conclusion

Consistent evidence reveals greater odds of obesity among U.S.-born Mexican-Americans relative to their first generation counterparts. This study extended this comparison by including those in Mexico, and revealed the gap between first generation immigrants and the U.S.-born is one part of a graded increase in obesity associated with migration to the U.S.. This is important in light of a longitudinal analysis that suggested first generation immigrants may be resistant to the obesogenic environment in the U.S. (ref) This cross-sectional comparison suggests otherwise. We found slight differences by gender, but results indicate a roughly three fold increase in obesity from one extreme to the other for both sexes.

Secondly, we found that among Mexicans with no direct migration experience, having a migrant in the immediate family is associated with higher risk for obesity among women, but not for men. This finding may reflect economic influences on diet such as cash remittances sent by migrants working in the U.S.

Findings should be interpreted in light of the use of cross-sectional data and reliance on self-report of height and weight. Self-reports tend to underestimate the prevalence of obesity, but evidence suggests that self-report does not differ between immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican-Americans, except for those who are underweight. 9

Migration is a transnational process that is likely to have a range of health effects in both sending and receiving countries, including diet. Given that obesity is a risk factor for the major causes of mortality in this country, growing rates among Mexican-Americans is of public health and clinical urgency.

Supplementary Material

‡ Adjusted for age, marital status, education, and smoking

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 7R01MH082023-04 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Dr Breslau). NIMH did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors, and each of their contribution is as follows. Overall integrity of the work from inception to publication: Flórez, Dubowitz, Breslau. Design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: Flórez, Dubowitz, Saito, Borges, Breslau. Preparation and review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Flórez, Dubowitz, Saito, Borges, Breslau. Final approval of the version to be published: Flórez, Dubowitz, Saito, Borges, Breslau. We are grateful to Dr. Kathryn Derose, Kristin Leuschner, Dr. Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola and Dr. Maria Elena Medina-Mora for providing comments on this manuscript.

References

- 1.Perez-Escamilla R. Acculturation, nutrition, and health disparities in Latinos. Am J Clin Nutr May. 2011;93(5):1163S–1167S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:309–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed May 10, 2012]; http://www.livestrong.com/thedailyplate/nutrition-calories/food/coca-cola/mexican-coca-cola-wreal-sugar/

- 4.http://productnutrition.thecoca-colacompany.com/products/coca-col

- 5.Park J, Myers D, Kao D, Min S. Immigrant obesity and unhealthy assimilation: alternative estimates of convergence or divergence, 1995-2005. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Dec;69(11):1625–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, et al. Prevalence, service use, and demographic correlates of 12-month DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in Mexico: results from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 2005 Dec;35(12):1773–1783. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SUDAAN [computer program] Research Trinagle Park, NC; p. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SK. Validity of self-reported weight and height: comparison between immigrant and non-immigrant Mexican Americans in NHANES III. J Immigr Health. 2005 Apr;7(2):127–131. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-2646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

‡ Adjusted for age, marital status, education, and smoking