Abstract

B lymphocytes can both positively and negatively regulate cellular immune responses. Previous studies have demonstrated augmented T cell-mediated tumor immunity in genetically B cell-deficient mice, suggesting that therapeutic B cell depletion would enhance tumor immunity. To test this hypothesis and quantify B cell contributions to T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune responses, mature B cells were depleted from wild type adult mice using CD20 mAb prior to syngeneic B16 melanoma tumor transfers. Remarkably, subcutaneous tumor volume and lung metastasis were increased two-fold in B cell-depleted mice. Effector-memory and IFNγ or TNFα-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cell induction was significantly impaired in B cell-depleted mice with tumors. Tumor Ag-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation was also impaired in tumor-bearing mice that lacked B cells. Thus, B cells were required for optimal T cell activation and cellular immunity in this in vivo non-lymphoid tumor model. While B cells may not have direct effector roles in tumor immunity, impaired T cell activation and enhanced tumor growth in the absence of B cells argues against previous proposals to augment tumor immunity through B cell depletion. Rather, targeting tumor Ags to B cells in addition to dendritic cells is likely to optimize tumor-directed vaccines and immunotherapies.

Keywords: Tumor Immunity, B Cells, T Cells

Introduction

B lymphocytes are the effector cells of humoral immunity that terminally differentiate into Ab-secreting plasma cells. However, B cells have multiple other functions that either positively or negatively influence cellular immunity. For example, B cells can positively regulate cellular immune responses by serving as APCs and/or by providing costimulatory signals to T cells (1, 2). Regulatory B cells (B10 cells) have also been identified that negatively regulate inflammation and immune responses through the production of IL-10 (3–5). Conflicting positive and negative roles for B cells during tumor immunity have also been reported. Ag presenting B cells can induce tumor-specific cytotoxic T cell activation (6). In addition, mice depleted of B cells since birth with anti-IgM serum do not develop fully protective T cell immunity to virus-induced tumors (7, 8). B cell Ab responses are thought to contribute modestly, if at all, to tumor immunity (9–11), while Ab production may contribute to chronic inflammation that enhances tumor development (12–14).

Negative regulatory functions for B cells during immune responses to tumors have also been proposed. Treatment of mice from birth with anti-IgM serum to deplete B cells increases their resistance to fibrosarcoma growth and lowers the incidence of metastasis (15). Mammary carcinoma invasion and metastasis are also reduced by 70% in mice subsequently treated with anti-IgM/IgG Ab (16). Tumors also grow more slowly and are rejected more frequently in severe combined immunodeficient mice given only T cells in contrast to mice reconstituted with both T and B cells (17). Other studies have predominantly used genetically B cell-deficient µMT mice, where B cell deficiency enhances CD4+ T cell priming and help for CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor immunity (10). B16 melanoma, EL4 thymoma, and MC38 colon carcinoma growth is also slowed in µMT mice (11). Similarly, anti-tumor immune responses to EL-4 thymoma and D5 melanoma are enhanced in µMT mice, potentially due to the absence of IL-10-producing B cells (18). B cell depletion in humans using rituximab, a chimeric anti-human CD20 mAb, may also delay or suppress advanced colon cancer progression and metastases (16). These results have led to the prediction that B cell depletion could therapeutically enhance immune responses to tumors. However, most of these studies were performed using mice in which the immune system develops in the complete absence of B cells. Because of this, µMT mice have severe immune system abnormalities (19). For example, T cell repertoire and numbers are decreased significantly in µMT mice (19, 20). In addition, B cells help to organize lymphoid organ architecture, so the spleens of µMT mice are smaller in size (20) and lack follicular dendritic cells and several macrophage populations (21). Moreover, dendritic cells produce enhanced levels of IL-12 in µMT mice, thus skewing immunity towards Th1 responses (22). Therefore, conclusively understanding the role of B cells in tumor immunity has been difficult. Furthermore, B cells may have different functions during immune responses to different tumors, much as B cells have reciprocal-regulatory functions during the development of autoimmunity (2, 4, 5, 23, 24).

The role of B cells during tumor immunity in wild type mice with intact immune systems was examined in this study using a mAb specific for CD20 that selectively depletes B cells in vivo by monocyte-mediated Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (25). More than 95% of mature B cells in the blood and primary lymphoid organs are depleted after two d by a single dose of MB20–11 CD20 mAb (250 µg per mouse), with the effect lasting up to eight weeks (26). To determine the role of B cells in tumor immunity, two physiologically relevant and well-characterized melanoma cell lines were used that were derived from a spontaneously-arising C57BL/6 melanoma (27, 28). B16/F10 cells were derived from the B16/F0 line after 10 successive in vivo passages (28, 29). These poorly-immunogenic tumor lines express low MHC class I levels and do not express MHC class II molecules, but both molecules are inducible upon IFN-γ exposure (30). B16/F10 cells are highly aggressive and metastatic, while B16/F0 cells metastasize less and are less aggressive (29, 31). Using these cells, B cell depletion in mice with otherwise intact immune systems was found to significantly accelerate melanoma growth and metastasis, and reduce the induction of CD4+ and CD8+ effector-memory and cytokine-secreting T cells. Thus, B cells are required for optimal T cell activation during this model of tumor immunity.

Materials and Methods

Mice, antibodies, and immunotherapy

C57BL/6, B6.PL Thy1a/Cy (B6.Thy1.1+), C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/JB6 (OT-II), and C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). OT-II and OT-I transgenic mice generate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that respond to peptides 323–339 and 257–264 of OVA, respectively (32, 33). OT-II and OT-I mice (Thy1.2+) were crossed to B6.Thy1.1+ mice to generate Thy1.1-expressing T cells for adoptive transfer experiments.

FITC-, PE-, PE-Cy5-, APC, or PE-Cy7-conjugated Thy1.1 (OX-7), CD4 (H129.19), CD8 (53–6.7), CD44 (IM7), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and TNFα (MP6-XT22) mAbs were from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA). L-selectin (CD62L; clone LAM1–116) mAb was as described (34). Functional grade CD3 (145–2C11) and CD28 (37.51) mAbs were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Fluorescently-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and IgM polyclonal Abs were from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL).

To induce in vivo B cell depletion, sterile and endotoxin-free CD20 (MB20-11, IgG2c) or isotype-matched control mAb (250 µg) were injected in 200 µl PBS through lateral tail veins (25). All mice were bred in a specific pathogen-free barrier facility and used at 6–12 weeks of age. All studies were approved by the Duke University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell lines and tumor models

B16/F10 melanoma cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The OVA-secreting B16/F0/OVA cell line (28) was kindly provided by Dr. Edith Lord (Univ. Rochester, Rochester, NY). A stable B16/F10 cell line expressing membrane-bound OVA (B16/F10/mOVA) was produced using an expression plasmid (pIRES2-EGFP) containing cDNA encoding full-length OVA protein linked to the transmembrane region of H-2Db (35), which was generously provided by Dr. Marc Jenkins (Univ. Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN). Cells expressing GFP at high levels were selected by multiple rounds of fluorescence-based cell sorting. Cells were passaged minimally and maintained in complete DMEM containing 10% FCS, 200 mg/ml penicillin, 200 U/ml streptomycin, 4 mM L-Glutamine, and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol (all from Invitrogen-Gibco, Carlsbad, CA). To maintain OVA expression, B16/F0/OVA and B16/F10/mOVA cell cultures contained G418 (400 µg/ml).

In the cutaneous melanoma tumor model, anesthetized mice were injected s.c. on the shaved right lateral flank with either 1 × 105or 1.5 × 106B16/F10, B16/F10/mOVA, or B16/F0/OVA tumor cells in 200 µl of sterile PBS. Tumor volumes were monitored and calculated using the equation: V = 4π(L1xL22)/3, where V = volume (mm3), L1 = the longest radius (mm), and L2 = the shortest radius (mm). In the lung metastasis model, between 4 × 104and 5 × 105B16/F10 or B16/F0/OVA tumor cells in 250 µl of sterile PBS were injected i.v. through lateral tail veins. At predetermined time points, lungs were removed from euthanized mice. The numbers of metastasis foci were counted visually in a blinded fashion using a stereomicroscope.

Measurement of tumor-specific Ab production

Serum Ab generated in response to tumors was evaluated using an indirect immunofluorescence assay. Sera from control or tumor-bearing mice were diluted 1:16 and incubated with B16/F0/OVA cells for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed extensively, incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated polyclonal anti-mouse IgG and IgM antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Background staining mean fluorescence intensity values (<10) were subtracted from the experimental values.

Cell preparation and immunofluorescence analysis

Single-cell leukocyte suspensions from spleens and peripheral lymph nodes (axillary, brachial, inguinal, and hilar) were generated by gentle dissection, and erythrocytes were hypotonically lysed. For multi-color immunofluorescence analysis, single cell suspensions (106cells) were stained at 4°C using predetermined optimal concentrations of mAb for 25 min, as described (36). Cells with the forward and side light scatter properties of lymphocytes were analyzed using either a FACScan or LSR-II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Background staining was assessed using non-reactive, isotype-matched control mAbs (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, CA).

Intracellular cytokine staining was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (Becton Dickinson) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. T cells were stimulated in vitro with plate-bound mAbs to CD3 (1 µg/ml) and CD28 (10 µg/ml) in the presence of Brefeldin A (1:1000 dilution; Becton Dickinson) for 3.5 h before surface staining and intracellular cytokine staining. In some experiments, CD19+ and CD19− cells were separated using CD19 mAb-coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA).

Adoptive transfer experiments

Donor Thy1.1+ OT-II or OT-I T cells from pooled spleens and lymph nodes were enriched with CD4+ and CD8+ T cell isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec), respectively, and labeled with CFSE Vybrant™ CFDA SE fluorescent dye (1 µM; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 2.5 × 106 labeled Thy1.1+ cells were administered i.v. to Thy1.2+ congenic recipients 1 d after tumor transfer. The proliferation of transferred cells was visualized by flow cytometry analysis of CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ cells. Transferred OT-II CD4+ or OT-I CD8+ T cells were identified by Thy1.1 and CD4 or CD8 mAb staining, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as means ± SEM. The significance of differences between sample means was determined using the Student’s t test.

Results

B cell depletion enhances B16 melanoma growth and metastasis

B cell contributions to non-lymphoid tumor immunity were assessed in adult wild type mice with otherwise intact immune systems following B cell depletion using CD20 mAb. Circulating, spleen, and lymph node B cell numbers are reduced >95% by day 2 in C57BL/6 mice, and begin to recover by day 57 following MB20-11 CD20 mAb treatment (250 mg/mouse, ref. 25, 26, 37). B16/F10 melanoma growth and metastasis were assessed in littermate mice given either control or CD20 mAb 7 d before the i.v. transfer of 3×105 B16/F10 melanoma cells. In this model of aggressive melanoma metastasis, tumor cells preferentially localize to the lungs where they appear as distinct pigmented foci on the lung surface (38).

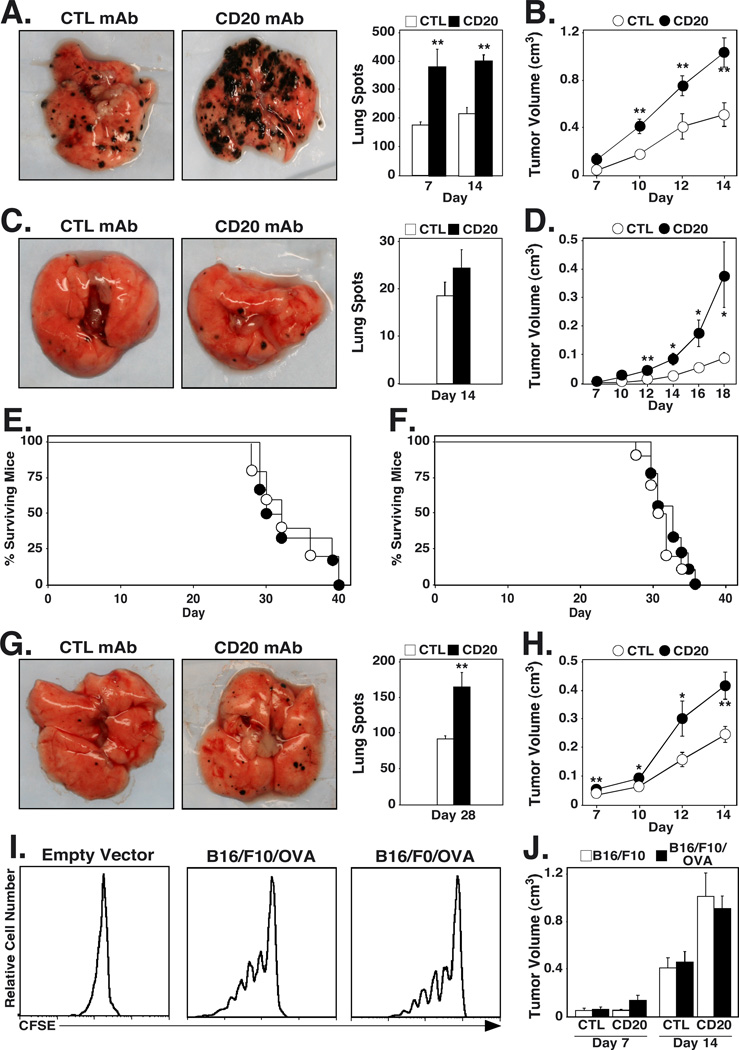

Two-fold more tumor foci were observed on the lungs of CD20 mAb-treated mice compared to control mAb-treated mice by 7 and 14 d following tumor injection (p≤0.006, Fig. 1A). Individual tumor foci were also larger and covered a greater surface area in B cell-depleted mice. Similar results were obtained when B cell-depleted mice were given 1.5 × 106 B16/F10 cells s.c. Tumor volumes at the site of injection were two-fold greater in B cell-depleted mice when compared with control mAb-treated mice 14 d after B16/F10 cell transfers (p≤0.005, Fig. 1B). When lower doses of B16/F10 cells were used, similar increases in subcutaneous tumor volume and lung tumor foci surface area were noted, while there was only a modest increase the in number of lung foci in CD20 mAb-treated mice (Fig 1C–D). Thus, B cell depletion may not directly affect tumor metastasis, but allows for increased growth of implanted tumor cells. However, increased tumor growth did not significantly affect the survival of CD20 mAb-treated mice that received i.v. injections of either low (Fig. 1E) or high (Fig. 1F) doses of B16/F10 cells.

FIGURE 1.

B cells enhance tumor immunity to B16 melanoma. (A, C, G) B cell depletion enhances B16 melanoma metastasis. Mice were given CD20 or control (CTL) mAb 7 d before i.v. transfer of (A) 3 × 105 B16/F10, (C) 5 × 104 B16/F10, or (G) 3 × 105 B16/F0/OVA cells. Representative lungs from control mAb- and CD20 mAb-treated mice 14 d (B16/F10 high dose), 14 d (B16/F10 low dose), or 28 d (B16/F0/OVA) after tumor transfer are shown. Histograms represent mean (± SEM) numbers of visible pigmented tumor foci on the surface of lungs on the indicated days after transfer (n≥5 mice for each group). (B, D, H) B cell depletion enhances B16 melanoma growth. Mice were given CD20 or control mAb 7 d before s.c. transfer of (B) 1.5 × 106 B16/F10, (D) 1 × 105 B16/F10, or (H) 1.5 × 106 B16/F0/OVA cells. Values represent mean tumor volumes (± SEM) at the site of transfer on the indicated days (n≥10 for each group). (E-F) Mouse survival following the i.v. transfer of (E) 4 × 104 or (F) 3 × 105 B16/F10 cells on day 0. All mice were given either control (open circles) or CD20 (closed circles) mAb on day −7 (n≥6 mice for each group). (I) B16/F10/mOVA cells activate OVA peptide-specific CD8+ T cells. Mice were given 3 × 105 i.v. B16/F10 cells transfected with an empty vector (Empty Vector, n=1), B16/F10 cells transfected to express OVA (B16/F10/mOVA, n=3), or B16/F0/OVA (n=3) cells 1 d before CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells from OT-I mice were transferred into each mouse. Lung-draining hilar lymph node lymphocytes were isolated 5 d later, with CFSE expression and dilution by CD8+Thy1.1+ T cells assessed by flow cytometry. Representative histograms showing CFSE intensity of CD8+Thy1.1+ cells are shown. (J) B16/F10 and B16/F10/mOVA have similar growth characteristics. Mice were given CD20 or control mAb 7 d before s.c. transfer of 1.5 × 106 B16/F10 or B16/F10/mOVA cells. Values represent mean tumor volumes (± SEM) at the site of transfer on the indicated days (n≥10 for each group). Significant differences between means for the same days are indicated: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

B cell depletion also facilitated the growth and metastasis of the B16/F0/OVA cell line, a substantially less aggressive tumor derived from the B16/F0 cell line. The frequency of detectable melanoma lesions in littermates given 5×105 B16/F0/OVA cells was significantly increased in the absence of B cells by day 28 (p=0.01; Fig. 1G). CD20 mAb treatment also significantly enhanced the growth of s.c. tumors 7 and 14 d after littermates were given 1.5 × 106 B16/F0/OVA cells (p=0.005, Fig. 1H). Thus, B cell depletion during tumor challenge enhanced the growth of both B16/F10 and B16/F0/OVA tumors.

To determine whether OVA expression affects B16 tumor growth, B16/F10 cells were stably transfected to express membrane-bound OVA (B16/F10/mOVA), and compared to wild type B16/F10 cells. OVA expression by both the B16/F0/OVA and B16/F10/mOVA cells was sufficient to stimulate the proliferation of CD8+ OVA peptide-specific OT-I cells in vivo (Fig 1I). Although both the wild type B16/F10 and B16/F10/mOVA cells grew similarly in control mAb-treated mice, both cell lines generated tumors that were twice as voluminous in CD20 mAb-treated mice (Fig. 1J). Thus, OVA expression by B16/F10 tumors did not affect tumor growth. Since all tumors responded similarly to B cell depletion and both the B16/F10/mOVA and B16/F0/OVA cells stimulated OT-I cells equally in vivo, the less aggressive and well-characterized B16/F0/OVA cells were utilized for all subsequent studies.

CD20 mAb effectively depletes B cells in tumor-bearing mice

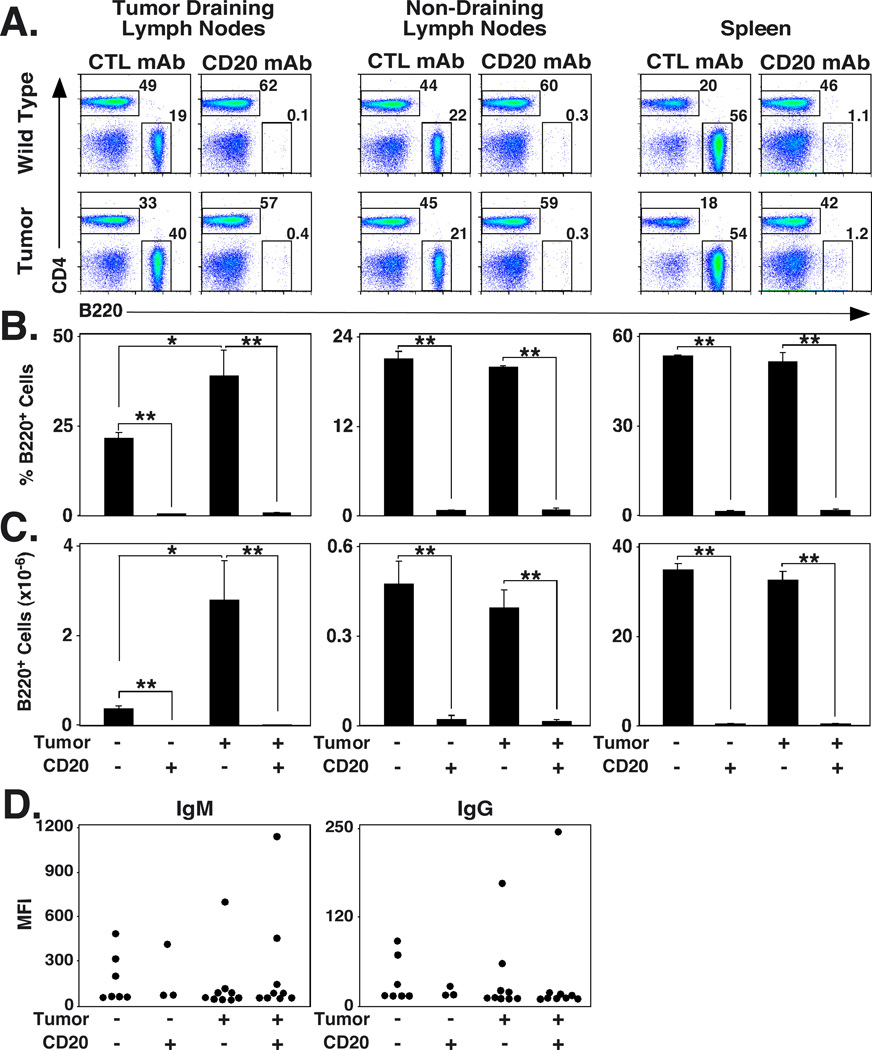

Whether B16/F0/OVA cells affect CD20 mAb-induced B cell depletion was assessed in tumor-free mice and mice receiving 1.5 × 106 B16/F0/OVA cells 7 d after control or CD20 mAb treatment. Fourteen days after tumor transfers, all mice had >0.15 cm3 s.c. tumors. The numbers of B220+ B cells within lymph nodes and spleens was assessed by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis. B220+ cell numbers in tumor-draining lymph nodes increased by 7.3-fold in tumor-bearing mice when compared with littermates without tumors (p<0.02; Fig. 2A–C). Nonetheless, CD20 mAb treatment depleted >99% of lymph node and spleen B cells in mice with or without tumors. Thereby, enhanced B16/F0/OVA growth in CD20 mAb-treated mice did not result from reduced B cell depletion.

FIGURE 2.

B cell depletion is effective in mice given B16 melanoma. (A) Representative B cell depletion in mice given CD20 or control (CTL) mAb 7 d before s.c. transfer of 1.5 × 106 B16/F0/OVA cells. Fourteen days after tumor transfers, tumor-draining lymph node (left panels), non-draining lymph node (middle panels), and spleen (right panels) lymphocytes were isolated and assessed for B220 and CD4 expression by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis. B220+ cell percentages within the indicated gates are shown for representative naïve (top panels) or tumor-bearing (bottom panels) mice. (B-C) Mean (± SEM) B220+ B cell (B) percentages and (C) total numbers in the tissues of control and tumor-bearing mice shown in (A) (n=3 for each group). (D) Ab responses to B16/F0/OVA cells are poor. B cells were depleted from mice as in (A), with serum collected from control or CD20 mAb-treated mice 14 d after tumor transfer. B16/F0/OVA cells were incubated with diluted serum, washed, and incubated with labeled anti-mouse IgM and IgG Abs before flow cytometry analysis. Circles represent the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of stained cells from individual mice that were treated as indicated. (B–D) Significant differences between means are indicated: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Anti-tumor Ab responses in B16/F0/OVA-bearing mice

Although B cell depletion abrogates most subsequent humoral immune responses to model Ags (39), the effects of CD20 mAb treatment on anti-tumor Ab responses is unknown. Therefore, mice were given control or CD20 mAb 7 d before s.c. transfer of B16/F0/OVA cells. Fourteen days later, OVA-specific IgM or IgG Ab responses were not detected in the serum of tumor-bearing mice by ELISA (data not shown). Therefore, B16/F0/OVA cells were incubated with diluted serum, washed, stained with fluorescently labeled anti-IgM or -IgG antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. No significant differences in tumor-reactive Ab levels were noted between control and B cell-depleted mice (Fig. 2D). Most control or tumor-bearing mice had similar low levels of B16/F0/OVA-reactive IgM and IgG antibodies regardless of CD20 mAb treatment. However, a small proportion of control and tumor-bearing mice had high titers of B16/F0/OVA-reactive IgM and IgG antibodies. As previously described, mice with significant B16-reactive Ab responses are likely to have previously produced IgM and IgG in response to viral Ags that are also expressed by B16/F0/OVA cells (40). Thus, C57BL/6 mice do not generate detectable B16/F0/OVA-specific Ab responses, consistent with previous observations (28, 41).

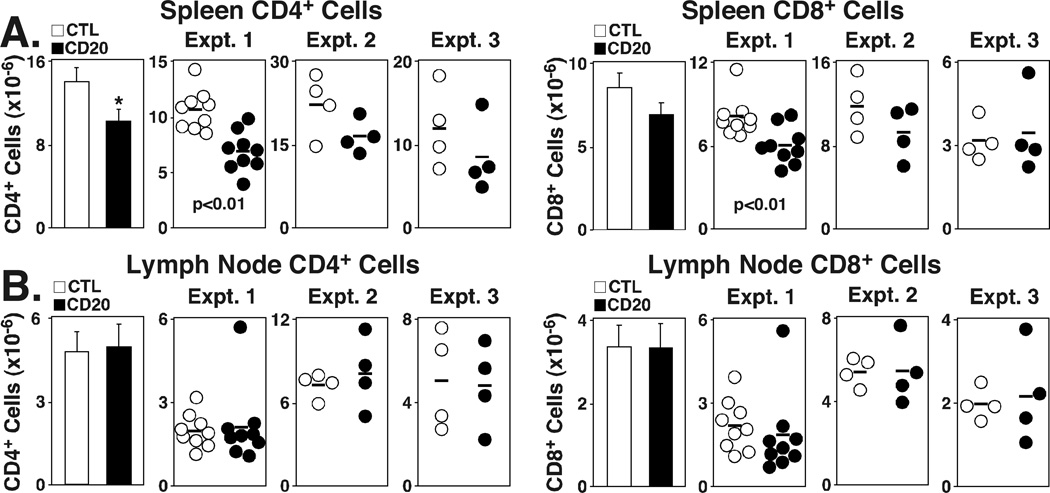

T cell numbers are reduced following B cell depletion

T cell and T cell subset numbers have not been significantly affected by short- (7 d) or long-term (28 d) B cell depletion (2, 5). To examine this further, spleen and lymph node T cell numbers were assessed in larger numbers of mice after 21–28 d of control or CD20 mAb treatment in three independent experiments. On average, there was a 27% decrease (p=0.02) in total splenic CD4+ T cell numbers in B cell-depleted mice (Fig. 3A). However, there was considerable variability between mice and between experiments. No significant difference was seen for splenic CD8+ T cell numbers when the experiments were pooled, although small decreases were observed in two of the three experiments. No differences in T cell numbers were detected within the peripheral lymph nodes of control- and CD20 mAb-treated mice (Fig. 3B). In addition, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cell numbers were modestly decreased in CD20 mAb-treated mice (Table I). These results suggest a small, but significant decrease in splenic CD4+ T cell numbers over time in naïve mice treated with CD20 mAb.

FIGURE 3.

B cell depletion reduces spleen CD4+ T cell numbers. Changes in (A) spleen or (B) peripheral lymph node CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers following B cell depletion. Circles represent individual mice that were given control (open) or CD20 (closed) mAb, with spleen and peripheral lymph node (pooled axial, inguinal, and brachial nodes) lymphocytes harvested 21 (experiment 1) or 28 (experiments 2–3) d later. Bar graphs indicate means (± SEM) of pooled CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers from all three experiments. Significant differences between means are indicated: *, p<0.05.

Table I.

CD4+ and CD8+ total and naïve T cell numbers in tumor-bearing micea

| Control mice |

Tumor-bearing mice |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Subset | Control mAb | CD20 mAb | Control mAb | CD20 mAb |

| Spleen: | Total CD4+ | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 9.68 ±1.06* | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 8.78 ±0.72* |

| Naïve CD4+ | 7.19 ± 0.43 | 6.18 ± 0.83 | 6.44 ± 0.47 | 5.42 ±0.56 | |

| CD4+CD25+FoxP3 | 1.89 ± 0.15 | 1.32 0.09** | 2.53 ± 0.24 | 1.75 ± 0.18* | |

| Total CD8+ | 8.21 ± 0.41 | 7.24 ± 0.62 | 7.13 ± 0.49 | 6.17±0.58 | |

| Naïve CD8+ | 5.92 ± 0.40 | 5.36 ± 0.61 | 4.92 ± 0.51 | 4.34 ± 0.60 | |

| Non-Draining Lymph Nodes: |

Total CD4+ | 1.94 ± 0.16 | 2.02 ± 0.36 | 2.02 ± 0.36 | 1.44 ± 0.25 |

| Naïve CD4+ | 1.67 ± 0.14 | 1.79 ± 0.33 | 1.79 ± 0.33 | 1.29 ±0.23 | |

| CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.36±0.06** | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.01** | |

| Total CD8+ | 1.20 ± 0.14 | 1.33 ± 0.22 | 1.07 ± 0.16 | 0.92 ± 0.15 | |

| Naïve CD8+ | 1.27 ± 0.11 | 1.14 ± 0.20 | 0.87 ± 0.13 | 0.78 ± 0.13 | |

| Tumor-draining Lymph Nodes: |

Total CD4+ | 2.47 ± 0.23 | 2.29 ± 0.24 | ||

| Naïve CD4+ |

2.08 ± 0.19 | 2.02 ± 0.22 | |||

| CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.06* | |||

| Total CD8+ | 1.90 ± 0.18 | 1.61 ± 0.18 | |||

| Naïve CD8+ | 1.53 ± 0.14 | 1.34 ± 0.15 | |||

Mice were given CD20 or control mAb 7 days before half of the mice in each group were given 1.5 × 106 s.c. B16/OVA tumor cells. Tissues were harvested 14 days later, with total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, naïve (CD44lowCD62L+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cell numbers (x10−6) determined by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis. Values for total and naïve T cells represent means (± SEM) from three groups of three mice in three separate experiments. Values for CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells represent means (± SEM) from five mice in each group. Non-draining lymph nodes in control mice consist of pooled bilateral inguinal, brachial, and axial lymph nodes. Significant differences between sample means are indicated

p≤0.05.

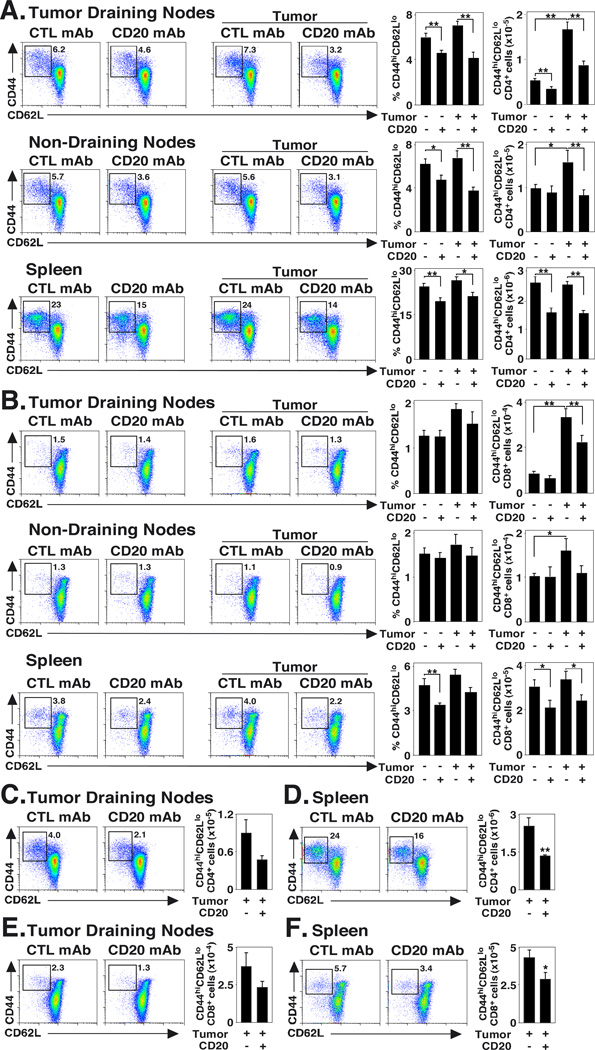

B cell depletion impairs CD4+ and CD8+ effector-memory T cell induction

Whether naïve or effector-memory T cell subset numbers decreased in B cell-depleted mice was assessed in mice given B16 tumors. Mice were given control or CD20 mAb 7 d before the s.c. transfer of B16/F0/OVA cells into half of the mice, with CD44 and CD62L expression by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells assessed 14 d after tumor transfers. Overall, B cell depletion did not have a significant effect on naïve (CD44loCD62Lhi) CD4+ or CD8+ T cell numbers in control or tumor-bearing mice (Table I). However, B cell depletion in control mice significantly reduced spleen CD4+ effector-memory (CD44hiCD62Llo) T cell numbers (39% decrease, p=0.0005; Fig. 4A). While effector-memory T cell numbers were increased >3-fold within the draining lymph nodes of control mAb-treated mice with B16/F0/OVA tumors (p<0.001), this increase was significantly reduced in B cell-depleted mice (42–48% decrease, p≤0.002) when compared with control mAb-treated mice with tumors. Similar differences were observed in non-tumor draining lymph nodes, with significantly fewer (49% decrease, p=0.01) CD4+ effector-memory cells in B cell-depleted mice when compared with control mAb-treated mice. CD4+ effector-memory T cell percentages and numbers were also decreased within the spleens of tumor-bearing mice treated with CD20 versus control mAb (21–38% decreases, p≤0.04). Similar results were observed in mice given s.c. B16/F10 cells or i.v. B16/F0/OVA cells (data not shown). CD4+ effector-memory T cell numbers were also decreased in B cell-depleted mice that received B16/F0/OVA cells at low doses (Fig. 4C–D).

FIGURE 4.

Effector-memory T cell induction is impaired in B cell-depleted tumor-bearing mice. Mice were given CD20 or control (CTL) mAb 7 d before half the mice in each group received 1.5 × 106 s.c. B16/F0/OVA cells. Fourteen days later, the frequencies and numbers of (A) CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ and (B) CD44hiCD62Llo CD8+ T cells within draining lymph nodes, non-draining lymph nodes, and spleens were determined by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis (n=9 for each group, pooled from three separate experiments in which n=3). C-F) Mice, treated as in (A–B), received 1 × 105 B16/F0/OVA cells, with (C–D) CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ and (E–F) CD44hiCD62Llo CD8+ T cell frequencies and numbers analyzed for tumor draining lymph nodes and the spleen (n=5 per group). Representative dot plots gated on CD44hiCD62Llo T cells are shown, with relative percentages indicated. Bar graphs indicate the mean (± SEM) percentages and numbers of CD44hiCD62Llo cells in the indicated treatment groups. Significant differences between sample means are indicated: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

There were no significant differences in lymph node CD8+ effector-memory T cell percentages or numbers between control and CD20 mAb-treated mice (Fig. 4B). However, B cell depletion did reduce CD8+ effector-memory T cell induction in mice with tumors. There were significantly fewer (33% decrease, p=0.01) CD8+ effector-memory T cells within the draining lymph nodes of B cell-depleted mice with tumors when compared to control mAb-treated mice with tumors. A similar trend was observed in the non-tumor draining lymph nodes. Spleen CD8+ effector-memory T cell numbers were also decreased by 29–31% (p=0.03) in B cell-depleted mice when compared with control mAb-treated mice, and in tumor-bearing mice given CD20 mAb in comparison with control mAb treatment. Decreased CD8+ effector-memory cell numbers were also seen in B cell-depleted mice that received low doses of B16/F0/OVA cells (Fig. 4E–F). Similar results were observed in mice given s.c. B16/F10 cells or i.v. B16/F0/OVA cells (data not shown). B cell depletion did not induce the apoptosis of effector-memory CD4+ and CD8+ cells, because Annexin-V staining of these populations was comparable between tumor-bearing control and CD20 mAb-treated mice (data not shown). Collectively, these results demonstrate that B cell depletion significantly impairs effector-memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell induction.

B cell depletion impairs IFNγ and TNFα induction by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo

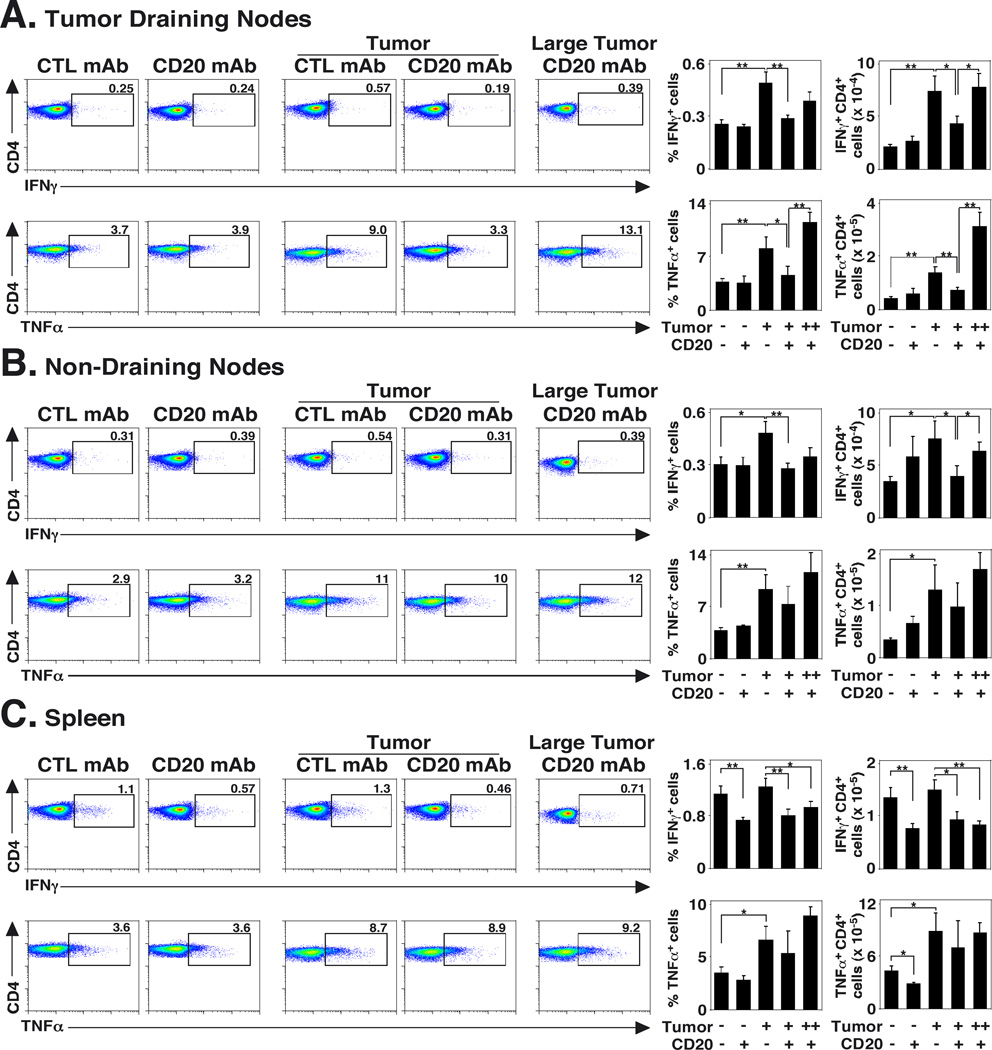

The in vivo effects of B cell depletion on IFNγ and TNFα production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were quantified as important markers for T cell stimulation due to their roles in tumor immunity. Mice were given control or CD20 mAb 7 d before B16/F0/OVA cells were transferred s.c. into half of the mice. Tumor draining lymph node, contralateral lymph node, and spleen lymphocytes were isolated 14 d after tumor transfers, with B cells removed using magnetic beads. The remaining non-B cells were cultured in vitro with plate-bound CD3 and CD28 mAbs for 3.5 h to identify T cells that were actively producing cytokines in vivo. The cells were stained for cell surface CD4 and CD8 as well as cytoplasmic IFNγ and TNFα expression, and were analyzed by flow cytometry. Comparisons were made between control and CD20 mAb-treated mice bearing tumors that were <0.25 cm3. B cell-depleted mice bearing tumors ≥0.25 cm3 were also analyzed, but their cytokine-secreting T cell numbers increased significantly with tumor size.

Percentages and numbers of IFNγ- and TNFα-secreting CD4+ T cells were similar in the lymph nodes of control mAb- or CD20 mAb-treated mice not given tumors (Fig. 5A–B). By contrast, total IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD4+ T cell numbers within tumor-draining lymph nodes were increased in control mAb-treated mice (∼3.5-fold, p<0.001) when compared to control mAb-treated mice not given tumors. The draining lymph nodes of B cell-depleted mice with <0.25 cm3 tumors had significantly smaller percentages (42–45% decrease, p≤0.04) and numbers (42–47% decrease, p≤0.02) of IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). Similar results were observed for IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells in the non-draining lymph nodes (Fig. 5B). By contrast, B cell depletion did not significantly affect the percentages or numbers of IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD4+ cells within tumor draining lymph nodes of mice with ≥0.25 cm3 tumors. There was a 44% decrease (p≤0.01) in IFNγ+ CD4+ T cell numbers and a 34% decrease (p=0.03) in TNFα+ CD4+ T cell numbers in the spleens of B cell-depleted mice not given tumors compared to control mAb-treated littermates (Fig. 5C). The spleens of B cell-depleted mice with tumors also contained significantly fewer (39% decrease, p=0.02) IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells when compared with control mAb-treated littermates with tumors. Thus, B cell depletion impaired the induction of IFNγ- and TNFα-secreting CD4+ T cells in response to B16/F0/OVA cells.

FIGURE 5.

B cell depletion impairs the induction of IFNγ- and TNFα-secreting CD4+ cells in tumor-bearing mice. Mice were given CD20 or control (CTL) mAb 7 d before half the mice in each group received 1.5 × 106 s.c. B16/F0/OVA cells. Fourteen days later, draining and non-draining lymph nodes and spleens were isolated, and B cells were removed using CD19 mAb-coated magnetic beads. The remaining non-B cells were cultured for 3.5 h with plate-bound CD3/CD28 mAbs before cell surface CD4 labeling and intracellular cytokine staining with flow cytometry analysis. Representative dot plots are shown for (A) tumor draining lymph nodes, (B) non-tumor draining lymph nodes, and (C) spleen CD4+ T cell expression of cytoplasmic IFNγ (upper panels) or TNFα (lower panels). Bar graphs indicate mean (± SEM) frequencies (left histograms) and numbers (right histograms) of CD4+IFNγ+ (upper panels) and CD4+TNFα+ (lower panels) cells in the indicated tissues of mice (n=6 for tumor-free control mice, n=6 for tumor-free CD20 mAb-treated mice, n=11 for tumor-treated control mice, and n=5 for CD20 mAb-treated mice with <0.25 cm3 tumors). Results from mice with tumors ≥0.25 cm3 (++) are also indicated (n=7). Significant differences between sample means are indicated: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

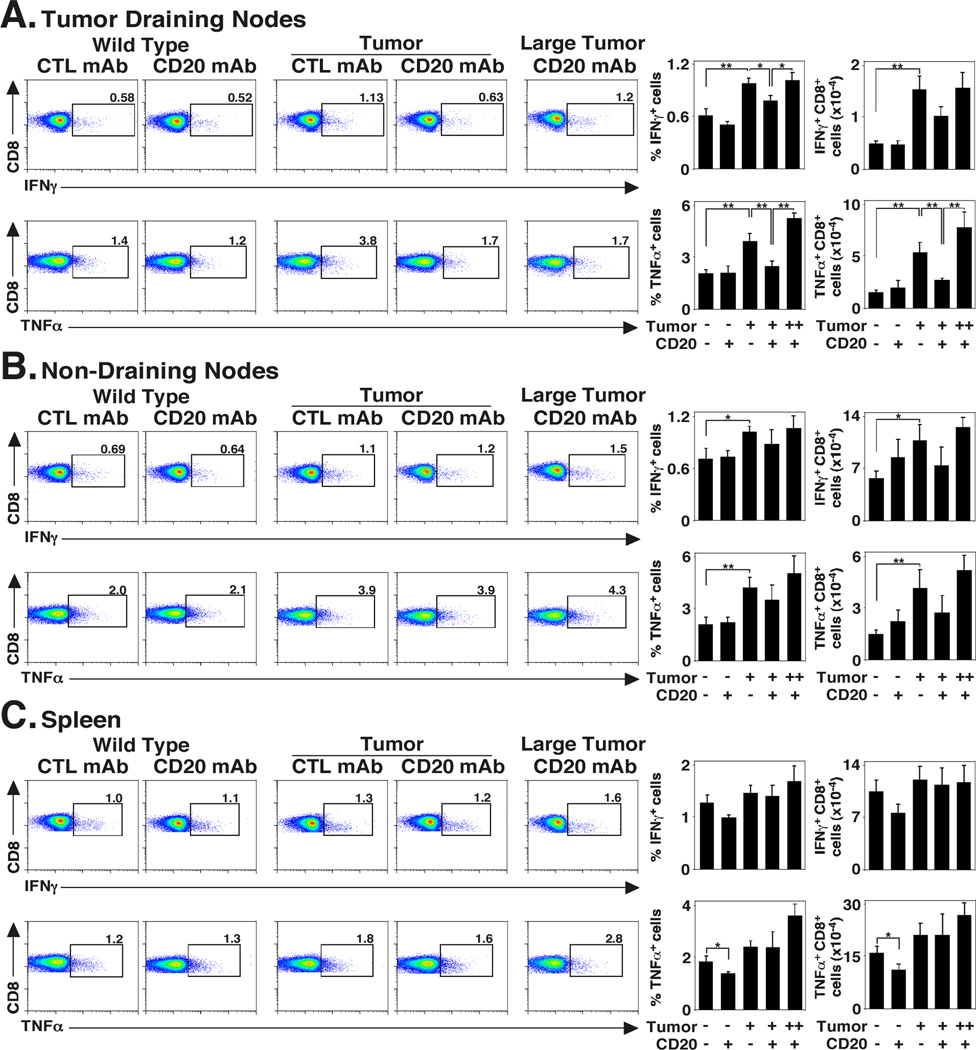

B cell depletion also affected the generation of cytokine-secreting CD8+ cells (Fig. 6). CD20 mAb treatment did not affect IFNγ+ or TNFα+ CD8+ T cell frequencies or numbers in mice not given tumors, except for TNFα-secreting CD8+ T cells within the spleen. IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD8+ T cell frequencies and numbers increased ≥3.2-fold (p=0.0007) within lymph nodes in control mAb-treated mice with tumors compared to control mAb-treated mice not given tumors (Fig. 6A). However, B cell depletion decreased the percentages (21% decrease, p=0.02) and numbers (34% decrease) of IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells within tumor-draining nodes of mice when compared to control mAb-treated mice with tumors. B cell depletion also reduced TNFα+ CD8+ T cell numbers in the draining lymph nodes of mice bearing <0.25 cm3 tumors by 50% (p=0.007) when compared to control mAb-treated mice with tumors. Similar frequencies and numbers of IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD8+ T cells were found within non-tumor draining nodes of CD20 and control mAb-treated mice (Fig. 6B). Few differences were seen in splenic IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD8+ T cell numbers between the experimental groups (Fig. 6C). Thus, B cell depletion predominantly reduced IFNγ or TNFα expression by CD8+ T cells within tumor-draining lymph nodes.

FIGURE 6.

B cell depletion impairs the induction of IFNγ- and TNFα-secreting CD8+ cells in tumor-bearing mice. Mice were treated as outlined in figure 5, except T cells expressing cell surface CD8 from (A) tumor draining lymph nodes, (B) non-draining lymph nodes, and (C) spleen were analyzed for cytoplasmic IFNγ (upper panels) or TNFα (lower panels) expression. Data presented are as outlined in figure 5.

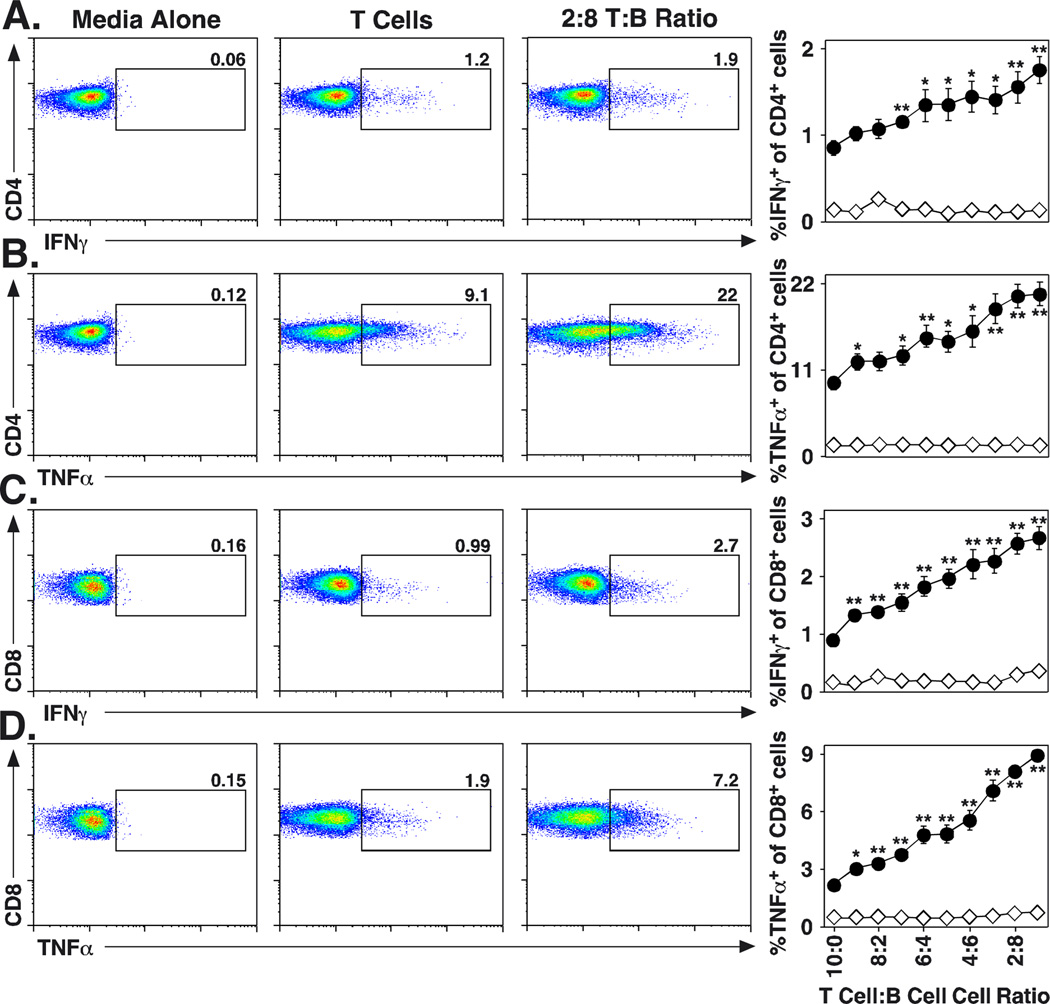

B cells are required for optimal T cell cytokine induction in vitro

To further verify a role for B cells in T cell cytokine induction in vivo, similar studies were carried out in vitro using purified B cells in short-term T cell induction assays. Splenic CD19+ B cells (>99% CD19+) and CD19− cells (T cells, <2% CD19+ cells) were purified and cultured with plate-bound CD3/CD28 mAbs for 3.5 h at varying T:B cell ratios before cell surface CD4 and CD8 staining, intracellular IFNγ and TNFα staining, and flow cytometry analysis. Plate-bound T cell stimulation was used to reduce the signaling contributions from B cell Fc receptor-mediated crosslinking of the CD3/CD28 mAbs that occurs with soluble mAbs. As B cells were increasingly added to the T cell cultures, there were significant increases in the frequencies of T cells expressing detectable intracellular IFNγ and TNFα. There was a 2-fold increase (p=0.0003) in CD4+ T cells producing IFNγ when B cells were present at 1:9 T:B cell ratios in comparison with T cells cultured alone (Fig. 7A). Similarly, TNFα-producing CD4+ T cell numbers increased 2.4-fold (p=0.001) when B cells were present at 1:9 T:B cell ratios in comparison with T cells alone (Fig. 7B). Significantly enhanced frequencies of CD8+ T cells produced IFNγ (3-fold increase, p=0.0005) and TNFα (4.4-fold increase, p<0.0001) when B cells were present in the cultures (Fig. 7C–D). By contrast, adding B cells to the cultures did not enhance the ability of unstimulated T cells to produce cytokines. Thereby, the presence of B cells significantly enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell cytokine production in response to CD3/CD28 stimulation.

FIGURE 7.

B cells are required for optimal T cell cytokine induction in vitro. Purified splenic B cells (>99% CD19+) and total splenocytes depleted of CD19+ cells (T cells, <2% CD19+) from naïve wild type mice were cultured for 3.5 h in media alone (open diamonds) or with plate-bound CD3/CD28 mAbs (filled circles) at varying T:B cell ratios (106 total lymphocytes per well) before staining for cell surface CD4 or CD8 and cytoplasmic cytokine expression with flow cytometry analysis. Representative flow cytometry analysis (left panels) of CD4+ T cells expressing cytoplasmic (A) IFNγ or (B) TNFα, or CD8+ T cells expressing (C) IFNγ or (D) TNFα are shown for various culture conditions. Line graphs indicate mean (± SEM) results from triplicate culture wells, and are representative of the results obtained in two independent experiments. Significant differences between sample means are indicated: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

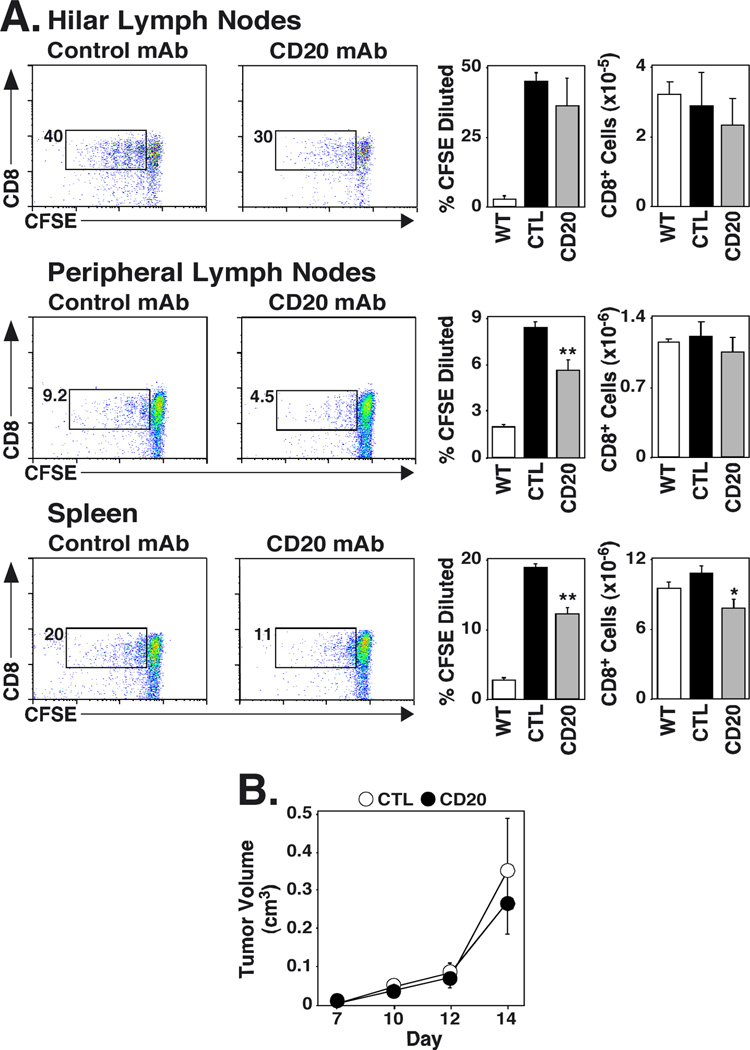

B cell depletion impairs tumor Ag-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation in vivo

The role of B cells in tumor Ag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation in vivo was assessed directly using the B16/F0/OVA cell line that secretes OVA protein, and OVA peptide-specific Thy1.1+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from OT-II and OT-I transgenic mice, respectively (32, 33). In agreement with previous studies (41, 42), OT-II cells did not proliferate in vivo in response to B16/F0/OVA tumors, even when harvested 10 d after transfer into tumor-bearing mice, while OT-I T cells proliferated in response to B16/F0/OVA tumors (data not shown). Mice were therefore treated with control or CD20 mAb 6 d before receiving B16/F0/OVA cells i.v. The following day, CFSE-labeled CD8+ OT-I T cells were adoptively transferred into the mice, with lung-draining hilar lymph nodes, peripheral lymph nodes, and spleens harvested 5 or 9 d later. Identical results were observed at both time points, so the data were pooled. There were no differences in OT-I T cell proliferation or numbers in hilar lymph nodes (Fig. 8). However, OT-I T cell proliferation was significantly reduced within peripheral lymph nodes (27% decrease, p=0.003) and spleens (35% decrease, p<0.0001) of B cell-depleted mice when compared with control mAb-treated littermates. Thus, B cell depletion did not reduce T cell entry into peripheral lymph nodes, but did reduce transgenic T cell proliferation. The significantly greater numbers of OVA-secreting tumor cells within the lungs of B cell-deficient mice compared to control mAb-treated mice (Fig. 1) may explain why OT-I cell proliferation was not reduced by B cell depletion within the lung-draining hilar lymph nodes. Nonetheless, these results directly demonstrate that CD8+ T cell expansion in response to tumor-specific Ags is impaired in B cell-depleted hosts.

FIGURE 8.

B cell depletion impairs tumor Ag-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation, but does not affect the growth of pre-established tumors. (A) Mice were given CD20 or control (CTL) mAb 6 d before receiving B16/F0/OVA cells i.v. One day later, the mice were adoptively-transferred with CFSE-labeled enriched Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells from OT-I mice. Lymphocytes from lung-draining hilar lymph nodes, peripheral lymph nodes, and spleens were isolated 5 or 9 d after OT-I cell transfer in two separate experiments, with CD8 expression and CFSE dilution for Thy1.1+ T cells assessed by flow cytometry analysis. The results from the 5 and 9 day studies were similar, if not identical, so the data were pooled. Representative CFSE versus cell surface CD8 staining for Thy1.1+ cells is shown, with the percentages of CFSE-diluted CD8+ cells within each gate indicated as a fraction of total CD8+ Thy1.1+ T cells. Bar graphs show the mean percentage (± SEM) of CFSE-diluted cells from tumor-free wild type mice (open bars, n=3), tumor-bearing control mAb-treated mice (closed bars, n=6), and tumor-bearing CD20 mAb-treated mice (shaded bars, n=6). The far right bar graphs show total numbers of CD8+ T cells within each tissue. Significant differences between sample means are indicated: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01. (B) Mice were given CD20 or control mAb 7 d after s.c. transfer of 105 B16/F10 cells, with tumor volumes measured on the indicated days.

B cell depletion does not affect the growth of established tumors

Whether B cell depletion enhances the growth of established tumors was assessed in mice given s.c. injections of 1 × 105 wild type B16/F10 cells 7 d before treatment with either control or CD20 mAb. Tumors in both control and CD20 mAb-treated mice grew with similar kinetics, and no significant differences were seen in tumor volumes 14 d after tumor challenge. Thus, established tumors grow equally well in the presence and absence of B cells.

Discussion

Mature B cell depletion in adult mice dramatically enhanced B16 melanoma tumor growth. Subcutaneous melanoma tumors were ∼2-fold larger and observable melanoma metastasis was enhanced ∼2-fold in the absence of B cells (Fig. 1). B cell depletion had modest, if any, effects on naïve T cell numbers (Table I). However, the induction of CD4+ and CD8+ effector-memory T cells (Fig. 4) and inflammatory and cytotoxic cytokine-secreting T cells (Figs. 5–6) was significantly impaired in B cell-depleted mice. Consistent with this, the presence of B cells significantly enhanced the frequency of cytokine-secreting T cells during short-term (3.5 h) in vitro cultures (Fig. 7). The ability of adoptively-transferred OVA-specific CD8+ T cells to proliferate in response to B16/F0/OVA tumors in vivo was also impaired in the absence of B cells (Fig. 8). Thus, these studies collectively demonstrate that B cells are required for optimal T cell activation and the induction of cellular immunity in this in vivo non-lymphoid tumor model. Thereby, while B cells may not have direct effector roles in tumor immunity, impaired T cell activation and effector-memory cell generation in the absence of B cells is likely to promote tumor growth in these immunocompromised hosts.

B cells can present Ags more efficiently than other APCs, and can present tumor Ags and autoantigens efficiently when the Ags are present at low concentrations (2, 43, 44). Specifically, B cells are not required for optimal CD4+ T cell activation at high Ag concentrations, while this responsibility is shared by B cells and dendritic cells when Ag or autoantigen concentrations are low (2). Furthermore, B cell MHC class II expression is required for maximal Ag-specific CD4+ T cell expansion, CD4+ memory formation, and CD4+ T cell cytokine production in vivo (1, 45). In addition, proteogylcan-induced arthritis is ameliorated and T cell activation and cytokine production are impaired in mice depleted of B cells with CD20 mAb (46, 47). B cells can also provide potent costimulatory signals for T cell expansion (48). In the case of weakly immunogenic tumors like B16 melanoma, the current studies demonstrate that B cells and other APCs are both involved in optimal CD4+ T cell expansion (Figs. 4–8). B cells have also been implicated in the contraction of CD8+ T cell responses and formation of memory CD8+ T cells during infections (49). Defective CD8+ T cell activation and memory formation may also result from impaired CD4+ T cell activation in the absence of B cells. In fact, the transfer of CD40-activated, tumor peptide-loaded B cells induces Ag-specific anti-tumor immune responses in mice via cross-presentation of Ag to APCs as well as direct T cell activation by the B cells (50). It is also possible that B cells may be responsible for generating Abs against disseminated forms of tumor antigens or their shed products (i.e. exosomes, gangliosides, B7-H1, etc.) that, at least locoregionally, promote the premature death of tumor-antigen experienced, but not naïve, T cells. Taken together, the results indicate that the absence of B cells during both the activation and expansion of tumor Ag-specific T cells explains the significant effects on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor immunity observed in this study.

We have previously reported that CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers do not change significantly after in vivo B cell depletion using CD20 mAbs (2, 5). While the current studies demonstrate that naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers predominantly remain constant within tissues after B cell depletion for 21 d, there was a significant reduction in CD44hiCD62Llo effector-memory T cells that affected total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers (Table I, Fig. 4). Thus, even though T cell numbers varied between mice after CD20 mAb treatment and between experiments (Fig. 3), there was a 20–27% decrease in spleen T cell numbers following prolonged B cell depletion (Fig. 3, Table I). It is unlikely that B cell depletion induces the death of T cells, since there is no decrease in total or effector-memory CD4+ or CD8+ T cell numbers 7 d after CD20 mAb injection (2), and effector-memory CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from the draining lymph nodes and spleen show similar Annexin-V staining in both control and CD20 mAb-treated mice (data not shown). Thus, the decrease in effector-memory T cell numbers 21 and 28 d after B cell depletion is most likely due to the impaired repopulation of effector-memory cells during normal turnover due to the suboptimal activation of T cells in the absence of B cells. That T cell numbers were not found to be significantly altered in previous experiments is likely due to short CD20 mAb treatment times, variability in effector-memory T cell subsets between groups of mice, insufficient numbers of mice within groups to detect small differences, or cell numbers were enumerated after immunizations with Ags in adjuvant. Modest decreases in CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell frequencies have also been noted in human CD20 transgenic MRL/lpr mice 10 weeks after treatment with 20 mg/week of an anti-human CD20 mAb (51). Nonetheless, the small decrease in T cell numbers observed in CD20 mAb-treated mice is consistent with decreased CD4+ T cell numbers in the spleens of B cell-deficient µMT mice (52).

Previous studies using non-lymphoid tumor lines in µMT mice have found that anti-tumor Th1 and cytotoxic T cell responses are enhanced and tumor growth is generally reduced in the absence of B cells (10, 11, 18, 53). Furthermore, reconstitution of µMT mice with wild type B cells abrogates their tumor resistance (11). In the absence of B cells, enhanced in vitro anti-tumor responses have also been observed following tumor Ag vaccinations (10, 53). That the T cell repertoire, lymphoid tissue architecture, and macrophage and dendritic cell numbers and function are all established in a wild type environment prior to B cell depletion using CD20 mAbs are the most likely explanations for differences between the current studies and previous studies using µMT mice (2, 4, 25, 26). In addition, the pro- or anti-tumor impact of B cells is likely to depend heavily on the tumor model being examined, due to the complex roles that B cells contribute to tumor immunity and other immune responses (3, 24). Regardless, the current studies using B cell-depleted mice collectively demonstrate that B cells unequivocally contribute to the development of anti-tumor immunity. In previous studies, an ability of B cells to negatively regulate anti-tumor immune responses was attributed to B cell provision of IL-10 (18), most likely by regulatory B10 cells (3, 4). In addition, partial B cell depletion in BALB/C mice using a different CD20 mAb than the one used in the current study suppressed the growth of a lung tumor cell line in vivo, indicating that B cells can negatively regulate tumor immunity (54). However, the remaining mature and marginal zone B cells left behind may have contributed to T cell activation in the absence of regulatory B10 cells (23). Although the absence of B cells in the current study inhibited the development of tumor immunity, this does not eliminate a potential inhibitory role for regulatory B10 cells during tumor immune responses, but rather indicates that the positive regulatory functions of B cells dominated in this context. Thus, it remains possible that regulatory B10 cells may inhibit immune responses at different stages of tumor progression or in response to different tumors. Thereby, selectively eliminating the negative influence of B10 cells during anti-tumor immune responses may potentiate the development of tumor immunity.

That B cells are required for T cell activation in the context of tumor immunity may also be applicable to multiple T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases where B cell depletion delays disease onset and reduces disease severity. Nonetheless, the current studies do not suggest or imply that B cell depletion in humans will promote or accelerate non-lymphoid tumor growth. The mouse anti-mouse CD20 mAb used in the current studies depletes the vast majority of mature B cells (25, 26, 39). Studies of B cell depletion in humans treated with rituximab predominantly focus on blood, where B cells represent <2% of total B cells. Thus, sufficient numbers of B cells may persist in human tissues after rituximab treatment to support T cell activation (55). Nonetheless, as with all forms of immunosuppression, cancer screening for patients considering B cell depletion therapies and paying attention to cancer rates in patients receiving B cell depletion therapies is warranted.

In conclusion, B cells are required for optimal cellular immune responses against B16 tumors in vivo, with B cell depletion reducing effector-memory and cytokine-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cell generation and the activation and proliferation of tumor Ag-specific CD8+ T cells. These results further confirm that B cells have significant functions, either as APCs and/or sources of costimulatory molecules in vivo when Ag concentrations are low, as occurs during tumor development. The therapeutic benefits from depleting B cells in autoimmunity are also likely to be attributable to reducing T cell contributions to disease symptoms. Thereby, these studies argue strongly against multiple previous proposals to augment anti-tumor immunity by depleting B cells and thereby augmenting Th1 responses (10, 11, 16, 18, 54). Conversely, targeting tumor Ags to B cells in addition to dendritic cells is likely to optimize tumor-directed vaccines and immunotherapies (50, 56).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Veronique Minard, Jonathan Poe, Karen Haas, Damian Maseda, and Michael Quigley for assistance with these studies, and LaToya McElrath for technical support. We also thank Dr. Edith Lord for providing the B16/F0/OVA cell line and Dr. Marc Jenkins for providing the mOVA construct.

Footnotes

These studies were supported by grants CA105001, CA9647, and AI56363 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Crawford A, Macleod M, Schumacher T, Corlett L, Gray D. Primary T cell expansion and differentiation in vivo requires antigen presentation by B cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176:3498–3506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouaziz JD, Yanaba K, Venturi GM, Wang Y, Tisch RM, Poe JC, Tedder TF. Therapeutic B cell depletion impairs adaptive and autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20882–20887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709205105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiLillo DJ, Matsushita T, Tedder TF. B10 cells and regulatory B cells balance immune responses during inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1183:38–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanaba K, Bouaziz J-D, Haas KM, Poe JC, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsushita T, Yanaba K, Bouaziz J-D, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3420–3430. doi: 10.1172/JCI36030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coughlin CM, Vance BA, Grupp SA, Vonderheide RH. RNA-transfected CD40-activated B cells induce functional T-cell responses against viral and tumor antigen targets: implications for pediatric immunotherapy. Blood. 2004;103:2046–2054. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon J, Holden HT, Segal S, Feldman M. Anti-tumor immunity in B-lymphocyte-deprived mice. III. Immunity to primary Moloney sarcoma virus-induced tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 1982;29:351–357. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910290320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz KR, Klarnet JP, Gieni RS, HayGlass KT, Greenberg PD. The role of B cells for in vivo T cell responses to a Friend virus-induced leukemia. Science. 1990;249:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.2118273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson LA. Anti-tumor immune responses of the tumor-bearing host: the case for antibody-mediated immunologic enhancement. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1994;72:1–8. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin Z, Richter G, Schuler T, Ibe S, Cao X, Blankenstein T. B cells inhibit induction of T cell-dependent tumor immunity. Nat. Med. 1998;4:627–630. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah S, Divekar AA, Hilchey SP, Cho HM, Newman CL, Shin SU, Nechustan H, Challita-Eid PM, Segal BM, Yi KH, Rosenblatt JD. Increased rejection of primary tumors in mice lacking B cells: inhibition of anti-tumor CTL and TH1 cytokine responses by B cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;117:574–586. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houghton AN, Uchi H, Wolchok JD. The role of the immune system in early epithelial carconogenesis: B-ware the double-edged sword. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:403–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte dependent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:411–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreiber H, Wu TH, Nachman J, Rowley DA. Immunological enhancement of primary tumor development and its prevention. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2000;10:351–357. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodt P, Gordon J. Anti-tumor immunity in B lymphocyte-deprived mice. I. Immunity to a chemically induced tumor. J. Immunol. 1978;121:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbera-Guillem E, Nelson MB, Barr B, Nyhus JK, May KF, Jr., Feng L, Sampsel JW. B lymphocyte pathology in human colorectal cancer. Experimental and clinical therapeutic effects of partial B cell depletion. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2000;48:541–549. doi: 10.1007/PL00006672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monach PA, Schreiber H, Rowley DA. CD4+ and B lymphocytes in transplantation immunity. II. Augmented rejection of tumor allografts by mice lacking B cells. Transplantation. 1993;55:1356–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue S, Leitner WW, Golding B, Scott D. Inhibitory effects of B cells on antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7741–7747. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joao C, Ogle BM, Gay-Rabinstein C, Platt JL, Cascalho M. B cell-dependent TCR diversification. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4709–4716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asano MS, Ahmed R. CD8 T cell memory in B cell-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:2165–2174. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowley MT, Reilly CR, Lo D. Influence of lymphocytes on the presence and organization of dendritic cell subsets in the spleen. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4894–4900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moulin V, Andris F, Thielemans K, Maliszewski C, Urbain J, Moser M. B lymphocytes regulate dendritic cell (DC) function in vivo: increased interleukin 12 production by DCs from B cell-deficient mice results in T helper cell type 1 deviation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:475–482. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouaziz J-D, Yanaba K, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells as inhibitors of immune responses and inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2008;224:201–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Matsushita T, Magro CM, St Clair EW, Tedder TF. B-lymphocyte contributions to human autoimmune disease. Immunol. Rev. 2008;223:284–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchida J, Hamaguchi Y, Oliver JA, Ravetch JV, Poe JC, Haas KM, Tedder TF. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1659–1669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamaguchi Y, Uchida J, Cain DW, Venturi GM, Poe JC, Haas KM, Tedder TF. The peritoneal cavity provides a protective niche for B1 and conventional B lymphocytes during anti-CD20 immunotherapy in mice. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4389–4399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, de Jong LA, Vyth-Dreese FA, Dellemijn TA, Antony PA, Spiess PJ, Palmer DC, Heimann DM, Klebanoff CA, Yu Z, Hwang LN, Feigenbaum L, Kruisbeek AM, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown DM, Fisher TL, Wei C, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Tumours can act as adjuvants for humoral immunity. Immunology. 2001;102:486–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidler IJ. Selection of successive tumour lines for metastasis. Nat. New Biol. 1973;242:148–149. doi: 10.1038/newbio242148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seliger B, Wollscheid U, Momburg F, Blankenstein T, Huber C. Characterization of the major histocompatibility complex class I deficiencies in B16 melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1095–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura K, Yoshikawa N, Yamaguchi Y, Kagota S, Shinozuka K, Kunitomo M. Characterization of mouse melanoma cell lines by their mortal malignancy using an experimental metastatic model. Life Sci. 2002;70:791–798. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based α - and β -chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steeber DA, Engel P, Miller AS, Sheetz MP, Tedder TF. Ligation of L-selectin through conserved regions within the lectin domain activates signal transduction pathways and integrin function in human, mouse and rat leukocytes. J. Immunol. 1997;159:952–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehst BD, Ingulli E, Jenkins MK. Development of a novel transgenic mouse for the study of interactions between CD4 and CD8 T cells during graft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1355–1362. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6135.2003.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou L-J, Smith HM, Waldschmidt TJ, Schwarting R, Daley J, Tedder TF. Tissue-specific expression of the human CD19 gene in transgenic mice inhibits antigen-independent B lymphocyte development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:3884–3894. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasegawa M, Hamaguchi Y, Yanaba K, Bouaziz J-D, Uchida J, Fujimoto M, Matsushita T, Matsushita Y, Horikawa M, Komura K, Takehara K, Sato S, Tedder TF. B-lymphocyte depletion reduces skin fibrosis and autoimmunity in the tight-skin mouse model for systemic sclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:954–966. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobrzanski MJ, Reome JB, Dutton RW. Type 1 and type 2 CD8+ effector T cell subpopulations promote long-term tumor immunity and protection to progressively growing tumor. J. Immunol. 2000;164:916–925. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiLillo DJ, Hamaguchi Y, Ueda Y, Yang K, Uchida J, Haas KM, Kelsoe G, Tedder TF. Maintenance of long-lived plasma cells and serological memory despite mature and memory B cell depletion during CD20 immunotherapy in mice. J. Immunol. 2008;180:361–371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sfondrini L, Morelli D, Bodini A, Colnaghi MI, Menard S, Balsari A. High level antibody response to retrovirus-associated but not to melanocyte lineage-specific antigens in mice protected against B16 melanoma. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;83:107–112. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<107::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preynat-Seauve O, Contassot E, Schuler P, Piguet V, French LE, Huard B. Extralymphatic tumors prepare draining lymph nodes to invasion via a T-cell cross-tolerance process. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5009–5016. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stoitzner P, Green LK, Jung JY, Price KM, Atarea H, Kivell B, Ronchese F. Inefficient presentation of tumor-derived antigen by tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2008;57:1665–1673. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0487-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivera A, Chen CC, Ron N, Dougherty JP, Ron Y. Role of B cells as antigen-presenting cells in vivo revisited: antigen-specific B cells are essential for T cell expansion in lymph nodes and for systemic T cell responses to low antigen concentrations. Int. Immunol. 2001;13:1583–1593. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiu Y, Wong CP, Hamaguchi Y, Wang Y, Pop S, Tisch RM, Tedder TF. B lymphocytes depletion by CD20 monoclonal antibody prevents diabetes in NOD mice despite isotype-specific differences in Fc y R effector functions. J. Immunol. 2008;180:2863–2875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linton PJ, Harbertson J, Bradley LM. A critical role for B cells in the development of memory CD4 cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:5558–5565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamel K, Doodes P, Cao Y, Wang Y, Martinson J, Dunn R, Kehry MR, Farkas B, Finnegan A. Suppression of proteoglycan-induced arthritis by anti-CD20 B cell depletion therapy is mediated by reduction in autoantibodies and CD4+ T cell reactivity. J. Immunol. 2008;180:4994–5003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanaba K, Hamaguchi Y, Venturi GM, Steeber DA, St.Clair EW, Tedder TF. B cell depletion delays collagen-induced arthritis in mice: arthritis induction requires synergy between humoral and cell-mediated immunity. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1369–1380. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linton PJ, Bautista B, Biederman E, Bradley ES, Harbertson J, Kondrack RM, Padrick RC, Bradley LM. Costimulation via OX40L expressed by B cells is sufficient to determine the extent of primary CD4 cell expansion and Th2 cytokine secretion in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Homann D, Tishon A, Berger DP, Weigle WO, von Herrath MG, Oldstone MB. Evidence for an underlying CD4 helper and CD8 T-cell defect in B-cell-deficient mice: failure to clear persistent virus infection after adoptive immunotherapy with virus-specific memory cells from μ MT/μ MT mice. J. Virol. 1998;72:9208–9216. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9208-9216.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ritchie DS, Yang J, Hermans IF, Ronchese F. B-Lymphocytes activated by CD40 ligand induce an antigen-specific anti-tumour immune response by direct and indirect activation of CD8+ T-cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2004;60:543–551. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahuja A, Shupe J, Dunn R, Kashgarian M, Kehry MR, Shlomchik MJ. Depletion of B cells in murine lupus: efficacy and resistance. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3351–3361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nozaki T, Rosenblum JM, Ishii D, Tanabe K, Fairchild RL. CD4 T cell-mediated rejection of cardiac allografts in B cell-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2008;181:5257–5263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perricone MA, Smith KA, Claussen KA, Plog MS, Hempel DM, Roberts BL, George JASt, Kaplan JM. Enhanced efficacy of melanoma vaccines in the absence of B lymphocytes. J. Immunother. 2004;27:273–281. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim S, Fridlender ZG, Dunn R, Kehry MR, Kapoor V, Blouin A, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. B-cell depletion using an anti-CD20 antibody augments antitumor immune responses and immunotherapy in nonhematopoetic murine tumor models. J Immunother. 2008;31:446–457. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31816d1d6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neelapu SS, Kwak LW, Kobrin CB, Reynolds CW, Janik JE, Dunleavy K, White T, Harvey L, Pennington R, Stetler-Stevenson M, Jaffe ES, Steinberg SM, Gress R, Hakim F, Wilson WH. Vaccine-induced tumor-specific immunity despite severe B-cell depletion in mantle cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2005;11:986–991. doi: 10.1038/nm1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schultze JL, Grabbe S, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS. DCs and CD40-activated B cells: current and future avenues to cellular cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:659–664. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]