Abstract

Mice subcutaneously injected with bleomycin, an experimental model for human systemic sclerosis, develop skin and lung fibrosis, which is mediated by inflammatory cell infiltration. This process is highly regulated by multiple adhesion molecules. To assess the role of adhesion molecules in this pathogenetic process, the bleomycin-induced fibrosis was examined in mice lacking adhesion molecules. In addition, this model does not require antigen sensitization. Therefore, we can exclude the possible role of adhesion molecules on the sensitization phase. L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency inhibited skin and lung fibrosis with decreased Th2 and Th17 cytokines and increased Th1 cytokines. By contrast, P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 deficiency augmented the fibrosis in parallel with increased Th2 and Th17 cytokines and decreased Th1 cytokines. Furthermore, loss of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 reduced Th2 and Th17 cell numbers in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, whereas loss of P-selectin, E-selectin, or PSGL-1 reduced Th1 cell numbers. Moreover, Th1 cells exhibited higher PSGL-1 expression and lower expression of LFA-1, a ligand for ICAM-1, while Th2 and Th17 cells showed higher LFA-1 and lower PSGL-1 expression. This study suggests that L-selectin and ICAM-1 regulate Th2 and Th17 cell accumulation into the skin and lung, leading to the development of fibrosis, and that P-selectin, E-selectin, and PSGL-1 regulate Th1 cell infiltration, resulting in the inhibition of fibrosis.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disease characterized by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition in the skin, lung, and other visceral organs with an autoimmune background (1). The presence of autoantibodies is a central feature of SSc, since antinuclear antibodies (Abs) are detected in >90% of patients (2). SSc patients have autoantibodies that react to various intracellular components, such as DNA topoisomerase I (topo I), centromeric protein B (CENP B), U1-ribonucleoprotein (RNP), and histone (2). Furthermore, abnormal activation of immune cells, including T cells, B cells, NK cells, and macrophages, has been identified in SSc (3). A recent study has shown that skin and lung fibrosis is ameliorated by treatment with cyclophosphamide, an immunosuppressive agent, indicating that immune activation leads to fibrosis through the stimulation of collagen production by fibroblasts (4). Indeed, SSc patients exhibit inflammatory cell infiltration, especially CD4+ T cells, and elevated serum levels of various cytokines, especially fibrogenic Th2 and Th17 cytokines and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, a major fibrogenic growth factor, which positively correlate with disease severity (5, 6).

In general, leukocyte recruitment into inflammatory sites is achieved using constitutive or inducible expression of multiple cell adhesion molecules (7). L-selectin (CD62L), E-selectin (CD62E), and P-selectin (CD62P) primarily mediate leukocyte capture and rolling on the endothelium (8). L-selectin is constitutively expressed by most leukocytes (8). While P-selectin is rapidly mobilized to the surface of activated endothelium or platelets, E-selectin expression is induced within several hours after activation with inflammatory cytokines (8). The selectins share a highly conserved N-terminal lectin domain that can interact with sialylated and fucosylated oligosaccharides such as sialyl-Lewis X (9). Although various candidates have been identified as potential ligands for selectins, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is the best-characterized ligand, which is recognized by all three selectins (10). PSGL-1 is a mucin-like, disulfide-linked homodimer expressed by all subsets of leukocytes and is a high-affinity ligand for E- and P-selectins (11). PSGL-1 has also been shown to bind to L-selectin, but its affinity is lower than E- and P-selectins (12). Intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (CD54) is a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily that is constitutively expressed not only on endothelial cells, but also on fibroblasts and epithelial cells (13). It can be up-regulated transcriptionally by several proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, and interleukin (IL)-1 (13). ICAM-1 forms the counterreceptor for the lymphocyte β2 integrines, such as leukocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1 (7). The ICAM-1/LFA-1 interactions predominantly mediate firm adhesion and transmigration of leukocytes at sites of inflammation (7). Inhibition of LFA-1 attenuated inratracheal bleomycin treatment-induced pulmonary fibrosis. However, the studies investigating the role of L-selectin and ICAM-1 in fibrosis are limited. Recent study has shown that intratracheal bleomycin treatment-induced pulmonary fibrosis is inhibited in L-selectin−/− mice and ICAM-1−/− mice (14). By contrast, another study has suggested that an antagonist of ICAM-1 does not attenuate intratracheal bleomycin treatment-induced pulmonary fibrosis, although the same treatment decreases leukocyte infiltration in the BAL (15). Thus, the in vivo contribution of L-selectin and ICAM-1 to fibrosis remains unclear.

Although these cell adhesion molecules play important roles in leukocyte transmigration, their association to inflammation remains controversial in several inflammatory models. Inhibition or loss of L-selectin, ICAM-1, P-selectin, E-selectin, or PSGL-1 leads to a significant reduction in leukocyte rolling and emigration in many inflammatory models, such as the tight-skin mouse model which is a genetic model for human SSc, immune complex deposition-induced tissue injury, contact hypersensitivity, intratracheal bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, and peritonitis (14, 16–21). By contrast, some studies have suggested that loss of P-selectin and/or E-selectin increases inflammatory response, such as experimental gromerulonephritis, collagen-induced arthritis, and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis models (22–25). Thus, E- and P-selectins regulate inflammatory response either positively or negatively according to the inflammatory models. Previous studies have shown that these cell adhesion molecules also regulate Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell migration. Inhibition or loss of ICAM-1 and/or L-selectin reduces Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell migration (26–28), while some studies suggest that Th1 and Th2 cell immigration is induced by L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency or blockade (26, 27, 29). P-selectin, E-selectin, and/or PSGL-1 deficiency or inhibition reduces Th1 and Th2 cell infiltration (28). Similarly, Th17 cell infiltration is significantly inhibited by E- and P-selectin deficiency (29). Thus, these cell adhesion molecules regulate Th cell balance, according to the tissue site and the nature of the inflammatory stimuli.

Recently, Yamamoto et al. established a new mouse model of SSc using bleomycin treatment: the subcutaneous injection of bleomycin induces fibrosis in the dermis and lung, autoantibody production, and dermal and pulmonary inflammatory cell infiltration, which closely mimics the features of human SSc (30). In this mouse model, B cells play important roles in the development of fibrosis (31). However, in the absence of CD19, which is a critical signal transduction molecule of B cells, bleomycin-induced fibrosis is not completely inhibited with ~30% reduction (31). This finding suggests that other immune cells and molecules also play important roles in the development of fibrosis. Although the contribution of cell adhesion molecules to disease manifestations, including autoimmunity, and to the mechanism underlying Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell infiltration remains unknown in the bleomycin-induced SSc model. In this study, we investigated the role of cell adhesion molecules in the development of fibrosis and autoimmunity induced by bleomycin using mice lacking L-selectin, ICAM-1, P-selectin, E-selectin, and PSGL-1. According to our results, L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency reduced dermal sclerosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and autoimmunity induced by bleomycin treatment with increased Th1 cell infiltration and decreased Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration. In contrast, P-selectin, E-selectin, or PSGL-1 deficiency augments disease manifestations induced by bleomycin treatment in parallel with decreased Th1 cell infiltration and increased Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration. These results suggest that L-selectin and ICAM-1 mainly regulate Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration, leading to the development of fibrosis, while P-selectin, E-selectin, and PSGL-1 mainly regulate Th1 cell infiltration, which results in the inhibition of fibrosis.

Materials and methods

Mice

L-selectin-deficient (L-selectin−/−) mice were produced as described elsewhere (32). ICAM-1−/−, P-selectin−/−, E-selectin−/−, and PSGL-1−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice lacking both L-selectin and ICAM-1 (L-selectin/ICAM-1−/−) were generated as described previously (18). All mice were backcrossed 10 generations onto the C57BL/6 genetic background. Mice used for experiments were 6 weeks old. Both body and lung size was similar for mutant and wild type mice (data not shown). All studies and procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Experimentation of Nagasaki University Graduate School of Medical Science.

Bleomycin treatment

Bleomycin (Nippon Kayaku, Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and sterilized by filtration. Bleomycin or PBS (300 μg) was injected subcutaneously into a single location on the shaved back of the mice daily for 4 weeks with a 27 gauge needle, as described previously (30). For blocking study, monoclonal Abs (mAbs) to P-selectin (RB40.34, rat IgG1, 30 μg per mouse; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were injected intravenously 30 minutes before first bleomycin or PBS treatment and three times per week into E-selectin−/−mice, as described previously (16).

Preparation of blonchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid

BAL cells were prepared as described elsewhere (23). Briefly, bleomycin- or PBS-treated mice were sacrificed and both lungs were excised. BAL fluid was collected as follows: 1 ml of saline was instilled three times and withdrawn from the lung via an intratracheal cannula. Total leukocyte counts were performed using a hemocytometer in the presence of trypan blue. Cell differential counts were determined after cytospin centrifugation with May-Giemsa staining. Neutrophils were identified morphologically in the BAL cells, as described previously (23). A total of 200 cells were counted from randomly chosen high-power microscopic fields for each sample and at least 10 mice of each group were examined.

Histopathological assessment of dermal fibrosis

Morphologic characteristics of skin sections were assessed under a light microscope. All skin sections were taken from the para-midline, lower back region (the same anatomic site, to minimize regional variations in thickness). Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Dermal thickness, defined as the thickness of skin from the top of the granular layer to the junction between the dermis and subcutaneous fat, was examined. Ten random measurements were taken per section. All of the sections were examined independently by two investigators in a blinded fashion. The skin from male mice was generally thicker than that from female mice in spite of the bleomycin or PBS treatment (data not shown). Since similar results were obtained when male or female mice were analyzed separately, only data from female mice were presented for skin thickness in this study. Mast cells were identified by toluidine blue staining. Cells containing metachromatic granules were counted in 10 random grids under high-magnification (x400) power fields of a light microscope.

Histopathological assessment of lung fibrosis

Lungs were excised after 4 weeks of treatment with bleomycin or PBS, processed as previously described, and stained by H&E and van Gieson to detect collagen. The severity of fibrosis was semi-quantitatively assessed according to Ashcroft et al (33). Briefly, the lung fibrosis was graded on a scale of 0 to 8 by examining randomly chosen fields of the left middle lobe at a magnification of x100. The grading criteria were as follows: grade 0, normal lung; grade 1, minimal fibrous thickening of alveolar or bronchiolar walls; grade 3, moderate thickening of walls without obvious damage to lung architecture; grade 5, increased fibrosis with definite damage to lung structure and formation of fibrous bands or small fibrous masses; grade 7, severe distortion of structure and large fibrous areas; and grade 8, total fibrous obliteration of fields. Grades 2, 4, and 6 were used as intermediate pictures between the aforementioned criteria. All of the sections were scored independently by two investigators in a blinded fashion.

Immunohistochemical staining

Frozen tissue sections of skin and BAL cells after cytospin centrifugation were incubated with rat mAb specific for macrophages (F4/80, Serotec, Oxford, UK), B220 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and CD3 (clone 145-2C11, BD PharMingen). Rat IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) was used as a control for nonspecific staining. Stained cells were counted in 10 random grids under high-magnification (x400) power fields of a light microscope. Each section was examined independently by two investigators in a blinded fashion.

Determination of hydroxyproline content in the skin and lung tissue

Hydroxyproline is a modified amino acid uniquely found at a high percentage in collagen. Therefore, the skin and lung tissue hydroxyproline content was measured as a quantitative measure of collagen deposition as previously described (18). The punch biopsy (6 mm) samples obtained from shaved dorsal skin and the harvested right lung of each mouse were analyzed. A hydroxyproline standard solution of 0 to 6 mg/ml was used to generate a standard curve.

Antinuclear Ab analysis

Antinuclear Abs were assessed by indirect immunofluorescence staining using sera diluted 1:50 and HEp-2 substrate cells (Medical & Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan) as described (31). Antinuclear Abs were detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated F(ab’)2fragments specific for mouse IgG + IgM + IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for serum cytokines, Igs, and autoantibodies

Sera were obtained by a cardiac puncture after 4 weeks of treatment with bleomycin or PBS and were stored at −80°C. Serum levels of IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, IFN-γ, TGF-β1, and TNF-α were assessed using specific ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). Serum Ig concentrations were assessed as described (31), using affinity-purified mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates) to generate standard curves. The relative Ig concentration of each sample was calculated by comparing the mean OD obtained for duplicate wells to a semi-log standard curve of titrated standard Ab using linear regression analysis. The specific ELISA kits were used to measure anti-topo I (Medical & Biological Laboratories), anti-CENP B (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan), and anti-U1-RNP (Medical & Biological Laboratories). These ELISA plates were incubated with serum samples diluted 1:100. Relative levels of autoantibodies were determined for each group of mice using pooled serum samples. Sera were diluted at log intervals (1:10–1:105) and assessed for relative autoantibody levels as above except that the results were plotted as OD versus dilution (log scale). The dilutions of sera giving half-maximal OD values were determined by linear regression analysis, thus generating arbitrary units per milliliter values for comparison between sets ofsera.

RNA isolation and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from lower back skin and lung with RNeasy spin columns (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). Total RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Expression of IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, IFN-γ, TGF-β1, and TNF-α was analyzed by an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), according to using a real-time PCR quantification method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequence-specific primers and probes were designed by Pre-Developed TaqMan Assay Reagents or Assay-On-Demand (Applied Biosystems). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate was used to normalize mRNA. Relative expression of real-time PCR products was determined by using the ΔΔCt method (31) to compare target gene and housekeeping gene mRNA expression.

Fibroblast culture and stimulation

Skin samples of 1 cm3 were taken from para-middle, lower back region of wild type mice. To obtain fibroblasts, the tissue was cut into 1-mm3 pieces, placed in sterile plastic dishes, and cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml of penicillin (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. After 2–3 weeks of incubation, the outgrowth of fibroblasts was detached by brief trypsin treatment and recultured in the medium. Confluent cultures of fibroblasts were serum-starved for 12 hours and then cultured with or without 10 ng/ml of murine recombinant IL-4 (rIL-4) and rIFN-γ and 50 ng/ml of murine rIL-17 (R&D systems) for 24 hours. We used fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD90.2 mAb (BD Biosciences) and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD45 mAb (Serotec) to differentiate fibroblasts and leukocytes (34). The CD45−CD90+ cells were recognized as fibroblasts. The purity of fibroblasts confirmed with flow cytometry was >99% with no leukocytes found in the harvested cells (data not shown). Furthermore, the purity of fibroblasts was assessed by microscopic examination of parallel samples grown on culture slides (BD Biosciences) and stained with H&E (data not shown), as previously described (35). In each experiment, obtained fibroblasts were examined at the same time and under the same conditions of cultures (for example, cell density, passage, and days after plating).

Fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis with IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-17 stimulation

Cultured dermal fibroblasts (1.2 × 104/well) were seeded into a 96-well plate. Fibroblasts were serum-starved for 12 hours and then cultured for 24 hours with or without 10 ng/ml of murine rIL-4 and rIFN-γ and 50 ng/ml of murine rIL-17 (R&D systems). Proliferation of cultured dermal fibroblasts was quantified by a colorimetric BrdU cell proliferation ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). After 24 hour incubation with or without rIL-4, rIFN-γ, and rIL-17, BrdU (10 μM) was added to each well and incubated for 24 hours. To analyze mRNA expression of proα2 (I) collagen (COL1A2) and TGF-β1, total RNA was isolated from fibroblasts shortly after 24 hours of incubation with or without murine rIL-4, rIFN-γ, and rIL-17.

Isolation and polarization of splenic T cells

Splenocytes were obtained from 6 to 8 weeks old wild type mice. Unless stated otherwise, all cell cultures were performed in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM of glutamine, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 mM of β-mercaptoethanol. T cells were enriched with a mouse CD4+ T cell kit using AutoMacs isolator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). A total of >99% of these cells were CD4+ when tested with anti-CD4 mAb (BD Biosciences; data not shown). Naive CD4+ T cells were obtained by surface staining with anti-CD62L, anti-CD44, and anti-CD25 mAb. The CD62L+CD44−CD25− population was isolated by flow cytometry cell sorting with a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). Cells were activated by plate-bound anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (5 μg/ml) mAbs for 3 days. Th0 condition indicated neutral condition (no exogenous cytokines and anti-cytokine Abs). Th1 condition indicates addition of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 Ab (10 μg/ml). Th2 condition indicates addition of IL-4 (10 ng/ml) and anti-IL-12 Ab (10 μg/ml). Th17 condition indicates addition of IL-6 (10 ng/ml), TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml), anti-IFN-γ mAb (10 μg/ml), and anti-IL-4 mAb (10 μg/ml). All cytokines were from R&D systems. All anti-cytokine Abs were from BD Pharmingen.

Flow cytometry

Abs used in this study included fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated mAbs to IL-4 (Imgenex, San Diego, CA), IFN-γ (Genetex, San Antonio, TX), and IL-17 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO); phycoerythrin-conjugated mAbs to IL-17 (BD Biosciences), L-selectin (BD Biosciences), LFA-1 (BD Biosciences), and PSGL-1 (BD Biosciences); and cyanine-5-phycoerythrin anti-CD4 mAb (Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA). Single-cell suspensions of BAL cells or CD4+ T cells were incubated with the Abs for 30 minutes at 4°C. The cells were washed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 production of BAL lymphocytes and cultured CD4+ T cells was determined by flow cytometric intracellular cytokine analysis, as previous described (36). Briefly, cells were suspended at 106/ml in RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM glutamine and incubated with 10 μg/ml of brefeldin A (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 2 hours at 37°C. Samples were stained for cell surface markers, PSGL-1, LFA-1, and CD4, for 30 minutes at 4°C. After permeabilizing with FACS permeabilizing solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Pharmingen), the cells were then stained for intracellular IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17. Cells were washed and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Pharmingen), analyzing data from 105 cells. Positive and negative population of cells was determined using unreactive isotype-matched mAbs (Bechman-Coulter, Brea, CA) as controls for background staining.

P-selectin, E-selectin, and ICAM-1 binding assay in polarized Th cells

We performed P-selectin, E-selectin, and ICAM-1 binding assays, as described previously (37). Recombinant mouse P-selectin, E-selectin, or ICAM-1/Fc chimera proteins were obtained from R&D systems. 5 × 104 Th0, Th1, Th2, or Th17 cells, which were isolated by flow cytometry cell sorting with a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences), were resuspended in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were incubated with 0.3 μg of each chimera protein for 30 minutes at 4°C and resuspended in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium containing fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (2 μg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). After incubation for another 30 minutes at 4°C, cells were analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Pharmingen), analyzing data from 105cells.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean values ± SD. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the level of significance of differences between sample means, and ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test was used for multiple comparisons.

Results

L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 loss attenuated the development of fibrosis induced by bleomycin, while P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 loss augmented it

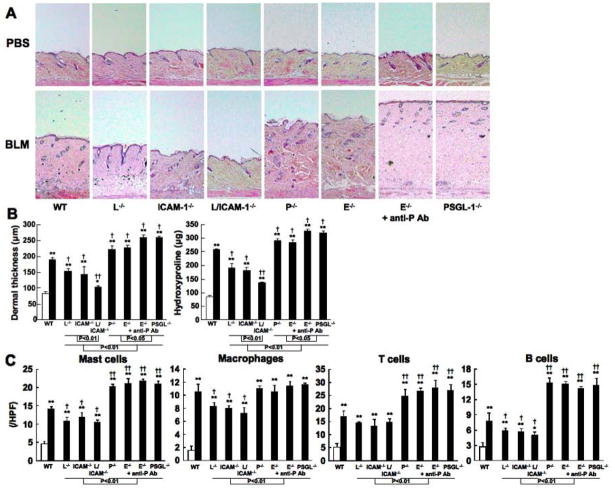

Bleomycin was injected subcutaneously into the back of mice daily for 4 weeks. Previous studies have shown that skin and lung fibrosis, epithelial injury, and inflammatory cell infiltration develop during the first 4 weeks of bleomycin treatment, peak in the fourth week, and begin to resolve 6 weeks after the cessation of treatment (30, 31). In this study, skin and lung fibrosis in mutant and wild type mice treated with either bleomycin or PBS was histopathologically assessed 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after bleomycin treatment. The dermal thickness (the thickness from the top of the granular layer to the junction between the dermis and subcutaneous fat) and lung fibrosis score showed time-dependent increase in bleomycin-treated mice (data not shown), which is consistent with previous studies (30, 31). After 4 weeks, bleomycin treatment induced significantly greater dermal thickness relative to PBS treatment in mutant and wild type mice (P < 0.05, Figure 1A, B). The dermal thickness was similar between nontreated and PBS-treated mice (data not shown). The dermal thickness in bleomycin-treated wild type mice significantly increased by 2.3-fold compared with PBS-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, Figure 1A, B). Bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− mice, ICAM-1−/− mice, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice showed moderate thickening of dermal tissue that was significantly 23%, 26%, and 49% thinner than that found in bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05), respectively. Moreover, skin thickness of bleomycin-treated L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice was thinner than that of bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− and ICAM-1−/− mice (P < 0.01). In contrast, the dermal thickness in bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P selectin mAb, and PSGL-1−/− mice was significantly 15%, 18%, 28%, and 31% thicker than that in bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, Figure 1A, B), respectively. Bleomycin-treated E-selectin−/− mice administrated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice showed the increased dermal thickness compared with bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05, Figure 1A, B). In addition, skin thickness of bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− mice, ICAM-1−/− mice, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice was significantly thinner than that of bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb, and PSGL-1−/− mice (P < 0.01, Figure 1A, B). Masson trichrome staining revealed thickened collagen bundles in the skin from bleomycin-treated wild type mice, which was reduced by L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency and was increased by P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 deficiency (data not shown). Cutaneous fibrosis was also assessed by quantifying hydroxyproline content of 10 mg of skin samples from mutant and wild type mice (Figure 1B). Although the hydroxyproline content in bleomycin-treated wild type mice was increased by 2.9-fold relative to that in PBS-treated wild type mice (P < 0.01), bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice reduced the hydroxyproline content by 29%, 31%, and 41% in bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). Moreover, the hydroxyproline content of bleomycin-treated L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice was significantly reduced compared with bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− and ICAM-1−/− mice (P < 0.01). In contrast, the hydroxyproline content was increased in bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice (10% increase), E-selectin−/− mice (9%), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (22%), and PSGL-1−/− mice (20%) compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, respectively, Figure 1B). Additionally, bleomycin-treated E-selectin−/− mice administrated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice showed further accumulation of the hydroxyprolin compared with bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/−and E -selectin−/−mice (P < 0.05, Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Skin fibrosis (A, B) and the numbers of mast cells, macrophages, T cells, and B cells at the bleomycin (BLM) injected site of skin (C) from PBS-treated (white bar) or BLM-treated (black bar) wild type (WT) mice, L-selectin−/− mice (L−/−), ICAM-1−/− mice (ICAM-1−/−), L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice (L/ICAM-1−/−), P-selectin−/− mice (P−/−), E-selectin−/− mice (E−/−), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (E−/− + anti-P Ab), and PSGL-1−/− mice (PSGL-1−/−). Representative histological sections stained with H&E are shown (original magnification x40, A). Skin fibrosis was assessed by quantitatively measuring dermal thickness and hydroxyproline content 4 weeks after BLM treatment (B). Mast cells were identified by toluidine blue staining, while macrophages, T cells, and B cells were stained with F4/80, anti-CD3 mAb, and anti-B220 mAb, respectively (C). These results represent those obtained with at least 10 mice of each group. The dermal thickness was measured under a light microscope. Cells were counted in 10 random grids under magnification of x400 high power fields (HPF). Each histogram shows the mean (± SD) results obtained for 10 mice of each group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus PBS-treated each group of the mice. † P < 0.05, †† P < 0.01 versus BLM-treated WT mice.

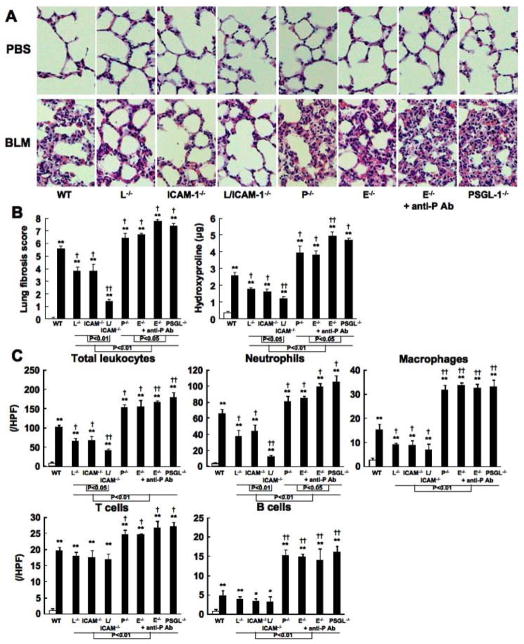

Similar results were obtained for the lung fibrosis score and the pulmonary hydroxyproline content (Figure 2A, B). After 4 weeks, bleomycin-treated wild type mice exhibited extensive inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis, granulomas, alveolar epithelial injury, and increased hydroxyproline content (Figure 2A, B). L-selectin or ICAM-1 deficiency reduced such histological changes and hydroxyproline content, while P-selectin, E-selectin, or PSGL-1 deficiency augmented it. Thus, skin and lung fibrosis induced by subcutaneous bleomycin injection was inhibited by L-selectin or ICAM-1 deficiency and was exacerbated by P-selectin, E-selectin, or PSGL-1 deficiency. Both L-selectin and ICAM-1 deficiency significantly inhibited skin and lung fibrosis relative to L-selectin or ICAM-1 deficiency alone. Furthermore, the deterioration effect of PSGL-1 deficiency or E-selectin deficiency with P-selectin blockade on skin and lung fibrosis was greater than that of P-selectin or E-selectin deficiency alone.

Figure 2.

Lung fibrosis (A, B) and the influx numbers of total leukocytes, including neutrophils, macrophages, T cells, and B cells, into BAL fluid (C) from PBS-treated (white bar) or bleomycin (BLM)-treated (black bar) wild type (WT) mice, L-selectin−/− mice (L−/−), ICAM-1−/− mice (ICAM-1−/−), L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice (L/ICAM-1−/−), P-selectin−/− mice (P−/−), E-selectin−/− mice (E−/−), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (E−/− + anti-P Ab), and PSGL-1−/− mice (PSGL-1−/−). Representative histological sections stained with H&E are shown (original magnification x100, A). Lung fibrosis was assessed by quantitatively measuring lung fibrosis score and hydroxyproline content 4 weeks after BLM treatment (B). The BAL cell counts were as described in the Materials and Methods section. These results were obtained from at least 10 mice in each group. Lung fibrosis score was measured under a light microscope. The differential BAL cells were counted in 10 random grids under magnification of x400 high power fields (HPF). Each histogram shows the mean (± SD) results obtained for 10 mice of each group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus PBS-treated each group. †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus BLM -treated WT mice.

Leukocyte infiltration into skin and lung was inhibited by L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 loss, while it was enhanced by P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 loss

The numbers of mast cells, macrophages, T cells, and B cells have been reported to increase in sclerotic skin and fibrotic lung from human SSc patients and bleomycin-induced SSc mouse models (31, 38). Therefore, the numbers of these immune cells were assessed in skin and blonchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid after 4 weeks of bleomycin treatment in mutant and wild type mice. The skin and BAL numbers of mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages, T cells, and B cells were greater in bleomycin-treated mice than in PBS-treated mice (P < 0.005, Figures 1C and 2C). In skin tissue, bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice exhibited lower numbers of these cells compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05), except T cell numbers (Figure 1C). By contrast, the numbers of mast cells, T cells, and B cells were greater in bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb, and PSGL-1−/− mice than in bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.01, Figure 1C).

In BAL cells, bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice showed decreased numbers of total leukocytes, including neutrophils and macrophages, compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, Figure 2C). Moreover, bleomycin-treated L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice showed lower numbers of total leukocytes and neutrophils than bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− and ICAM-1−/− mice (P < 0.05, Figure 2C). However, T cell and B cell numbers in BAL fluid were similar among bleomycin-treated wild type, L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice. In contrast, the numbers of total leukocytes, including neutrophils, macrophages, T cells, and B cells, significantly increased in bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb, and PSGL-1−/− mice compared to those in bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice exhibited further increased numbers of neutrophils relative to bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05, respectively). Thus, inflammatory cell recruitment to BAL fluid was inhibited by L-selectin or ICAM-1 deficiency. Furthermore, both L-selectin and ICAM-1 deficiency inhibited this recruitment more strongly than L-selectin or ICAM-1 deficiency alone. In contrast, P-selectin or E-selectin deficiency alone induced inflammatory cell recruitment to BAL fluid. Moreover, this increasing effect of E-selectin deficiency with P-selectin blockade and PSGL-1 deficiency was greater than that of P-selectin or E-selectin deficiency alone.

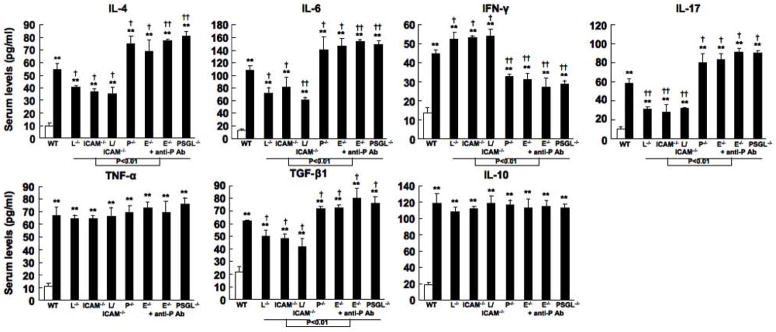

Effect of cell adhesion molecule deficiency or blockade on cytokine production

It has been suggested that IL-4, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17, TNF-α, TGF-β1, and IL-10 production contributes to bleomycin-induced fibrosis by regulating the collagen production by fibroblasts (30, 31, 39, 40). Therefore, in the serum, sclerotic skin, and fibrotic lung, the production of these cytokines was assessed by ELISA and real-time PCR. In the serum, skin, and lung, bleomycin-treated mutant and wild type mice had elevated levels of IL-4, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17, TNF-α, TGF-β1, and IL-10 compared with PBS-treated mutant and wild type mice (P < 0.01, respectively). Serum levels of IL-4, IL-6, IL-17, and TGF-β1 were reduced in bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice relative to bleomycin-treated wild type mice, while serum levels of IFN-γ was higher in these mice than bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, Figure 3A). By contrast, bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb, and PSGL-1−/− mice exhibited elevated levels of IL-4, IL-6, IL-17, and TGF-β1 compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05), while they showed lower levels of IFN-γ than bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, Figure 3A). There were no significant differences in serum levels of TNF-α and IL-10 between bleomycin-treated mutant and wild type mice. Similar results were obtained for mRNA expression levels in the skin and lung (data not shown), except that bleomycin-treated L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice showed lower expression levels of IL-4, IL-17, and TGF-β1 in the skin and lung and IL-6 in the lung than L-selectin−/− and ICAM-1−/− mice (P < 0.05). In lung tissue, ICAM-1−/− mice exhibited lower IL-17 expression than L-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05). Moreover, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice exhibited higher expression levels of IL-4, IL-17, and TGF-β1 in the skin and lung and IL-6 in the lung than P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05). In contrast, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice exhibited a reduction in skin IFN-γ expression that was significantly lower than that found in P-selectin−/− mice as well as E-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05, respectively). Thus, in the serum, sclerotic skin, and fibrotic lung, bleomycin treatment induced the overexpression of various cytokines. L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency reduced expression levels of fibrotic Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-6, IL-17, and TGF-β1, a major fibrogenic growth factor, while P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 deficiency increased it. In contrast, L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency increased expression of IFN-γ, antifibrotic Th1 cytokine, while P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 deficiency decreased it.

Figure 3.

Levels of IL-4, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17, TNF-α, TGF-β1, and IL-10 in serum samples from wild type (WT) mice, L-selectin−/− mice (L−/−), ICAM-1−/− mice (ICAM-1−/−), L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice (L/ICAM-1−/−), P-selectin−/− mice (P−/−), E-selectin−/− mice (E−/−), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (E−/− + anti-P Ab), and PSGL-1−/− mice (PSGL-1−/−) treated with either PBS (white bar) or bleomycin (black bar). Serum samples were obtained by a cardiac puncture 4 weeks after treatment with either bleomycin or PBS. Serum cytokine levels were assessed using specific ELISA. Each histogram shows the mean (± SD) results obtained for 10 mice of each group. ** P < 0.01 versus PBS-treated each group. †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus BLM -treated WT mice.

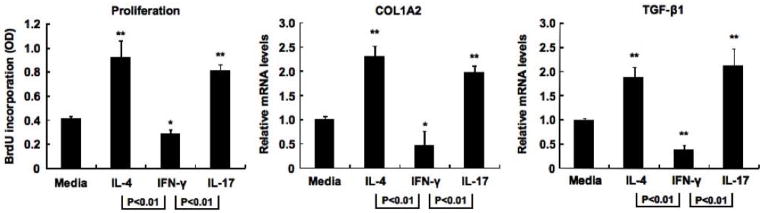

Effect of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines on dermal fibroblasts

We investigated the effect of IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-17 on function of fibroblasts obtained from wild type mice (Figure 4). Stimulation with IL-4 and IL-17 significantly increased fibroblast proliferation compared to media alone (P < 0.01, respectively). In contrast, IFN-γ stimulation inhibited fibroblast proliferation compared to media alone (P < 0.05). COL1A2 and TGF-β1 mRNA expression was quantified by real-time PCR in cultured dermal fibroblasts. COL1A2 and TGF-β1 mRNA levels in fibroblasts significantly increased by IL-4 and IL-17 stimulation, while they decreased by IFN-γ stimulation compared with media alone (P < 0.01, respectively).

Figure 4.

Proliferation and collagen synthesis of dermal fibroblasts obtained from wild type (WT) mice. Cultured fibroblasts were serum starved for 12 hours and then cultured for 24 hours with murine rIL-4 (10 ng/ml), rIFN-γ (10 ng/ml), and rIL-17 (50 ng/ml). Total RNA from fibroblasts was extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA, and mRNA expression of COL1A2 and TGF-β1 was analyzed by real-time PCR. In proliferation assay, after 24 hour incubation, BrdU (10 μM) was added to each well and incubated for 24 hours. BrdU incorporation in proliferating cells was quantified by ELISA. Each histogram shows the mean (± SD) results obtained for 6 mice of each group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus fibroblasts cultured with media alone.

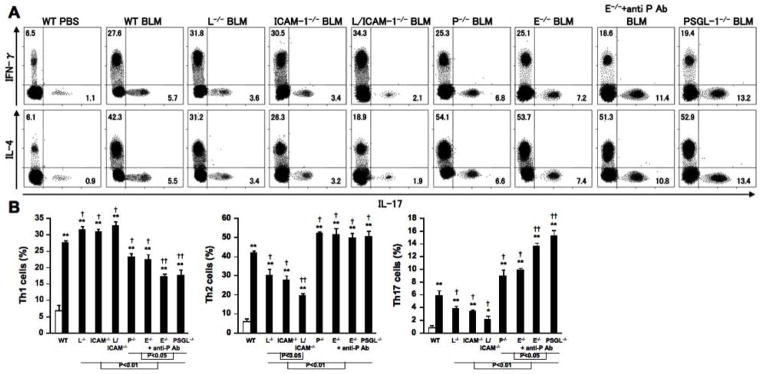

Infiltration of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells was regulated by cell adhesion molecules in the bleomycin-induced SSc mouse model

We investigated Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell frequencies in BAL fluid from bleomycin-treated mutant and wild type mice (Figure 5). Bleomycin-treated mutant and wild type mice exhibited significantly increased frequencies of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells compared with PBS-treated mutant and wild type mice in the BAL fluid (P < 0.01, Figure 5B) but not in homogenate lung parenchyma (data no shown). There were no significant differences in Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell frequencies between PBS-treated mutant and wild type mice (Figure 5B). The population expressing IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-17 did not overlap (Figure 5A), which is consistent with previous studies (36). Bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced Th2 and Th17 cell frequencies and significantly increased Th1 cell frequencies in BAL fluid compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, respectively; Figure 5B). L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice displayed further reduction of Th2 and Th17 cell influx into BAL fluid relative to L-selectin−/− and ICAM-1−/− mice (P < 0.05). Th1 cell frequencies were significantly reduced in bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). The reducing effect of E-selectin loss with P-selectin blockade and PSGL-1 loss on Th1 cell influx was greater than that of P-selectin or E-selectin deficiency alone (P < 0.05). Bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice, E-selectin−/− mice with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1−/− mice also exhibited significantly increased Th2 and Th17 cell frequencies in BAL fluid compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05, respectively). Moreover, E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice displayed higher frequencies of Th17 cells compared with P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05). Thus, these results suggest that L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency inhibits Th2 and Th17 cell influx into BAL fluid, while Th1 cell infiltration is induced by L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency. P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 loss inhibit Th1 cell influx and induce Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration.

Figure 5.

Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell frequencies of BAL in PBS-treated (white bar) or bleomycin (BLM)-treated (black bar) wild type (WT) mice, L-selectin−/− mice (L−/−), ICAM-1−/− mice (ICAM-1−/−), L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice (L/ICAM-1−/−), P-selectin−/− mice (P−/−), E-selectin−/− mice (E−/−), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (E−/− + anti-P Ab), and PSGL-1−/− mice (PSGL-1−/−). We determined Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells by surface CD4 expression and intracellular expression of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 as previously described (36). BAL fluid was analyzed by flow cytometry after 4 weeks PBS or BLM treatment. These data are representative of three independent experiments (A). Percentages of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells are shown in the each quadrant. We also show summaries of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell frequencies in each group (B). Each histogram shows the mean (± SD) results obtained for 10 mice of each group. * P < 0.005, ** P < 0.001 versus PBS-treated each group. † P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus BLM -treated WT mice.

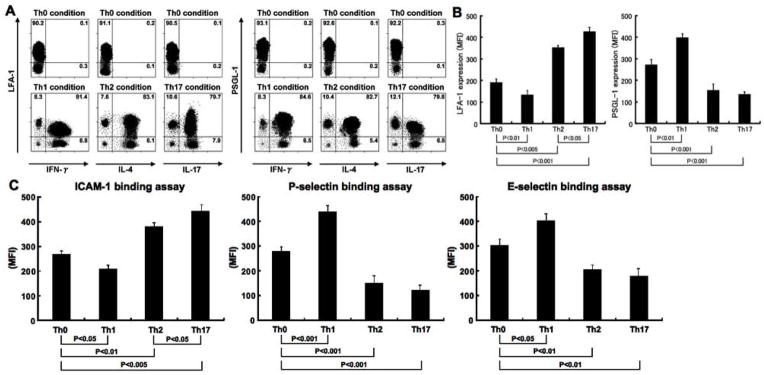

Expression of LFA-1 and PSGL-1 on polarized Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells

To investigate how cell adhesion molecules regulate Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell infiltration, expression of LFA-1, a ligand of ICAM-1, and PSGL-1 in polarized Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells and non-polarized Th0 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 6). In Th0 cells obtained from Th0 condition, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 expression was hardly detectable (Figure 6A). In Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells obtained from Th1, Th2, and Th17 condition, respectively, the population expressing IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-17 did not overlap (data not shown). Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells did not express L-selectin (data not shown). Th1 cells showed lower LFA-1 expression and ICAM-1 binding ability compared with Th0 cells (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively; Figure 6B, C). By contrast, Th1 cells exhibited higher PSGL-1 expression and P-selectin and E-selectin binding ability relative to Th0 cells (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, and P < 0.05, respectively). Although LFA-1 expression and ICAM-1 binding ability increased in Th2 and Th17 cells compared with Th0 cells (P < 0.01, respectively), Th2 and Th17 cells exhibited lower expression levels of PSGL-1 and P-selectin and E-selectin binding ability (P < 0.01, respectively). In addition, LFA-1 expression levels and ICAM-1 binding ability in Th17 cells were greater than those in Th2 cells (P < 0.05, respectively). There was no significant difference in the frequencies of LFA-1+ or PSGL-1+ cells among Th0, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells (Figure 6A). These results suggest that PSGL-1 is preferentially used to recruit Th1 cells into inflammatory lesions, while Th2 and Th17 cells dominantly use LFA-1.

Figure 6.

The LFA-1 and PSGL-1 expression levels (A and B) and ICAM-1, P-selectin, and E-selectin binding ability (C) in Th0, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells. We determined Th0, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells by surface CD4 expression and intracellular expression of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 as previously described (36). Polarized or nonpolarized splenic CD4+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. These data are representative of three independent experiments. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each quadrant. Histograms indicate mean (± SD) fluorescence intensity (MFI).

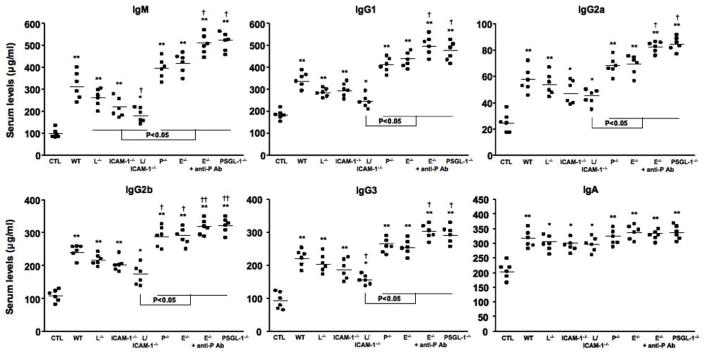

Contribution of cell adhesion molecules to Ig production

Serum Ig levels in bleomycin-treated mutant and wild type mice were also investigated (Figure 7). PBS-treated mutant mice had similar IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA levels to PBS-treated wild type mice (data not shown). Bleomycin treatment increased serum IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA levels compared with PBS treatment (P < 0.05, respectively). L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice treated with bleomycin had decreased IgM and IgG3 levels compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05), while the levels of other isotypes were similar among bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, L-selectin/ICAM-1−/−, and wild type mice. P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice administrated with bleomycin had increased IgG2b levels compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05), while there were no significant differences in the levels of other isotypes among bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/−, E-selectin−/−, and wild type mice. In E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice, bleomycin administration increased serum levels of all Ig isotypes, except IgA, compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). Thus, treatment with bleomycin induced hyper-γ-globulinemia, which was inhibited by L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 loss, while the loss of P-selectin, E-selectin with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 augmented Ig production.

Figure 7.

Serum Ig levels in bleomycin-treated wild type (WT) mice, L-selectin−/− mice (L−/−), ICAM-1−/− mice (ICAM-1−/−), L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice (L/ICAM-1−/−), P-selectin−/− mice (P−/−), E-selectin−/− mice (E−/−), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (E−/− + anti-P Ab), and PSGL-1−/− mice (PSGL-1−/−). Serum Ig levels in PBS-treated WT mice were used as control Ig levels (CTL). Serum Ig levels were determined by isotype-specific ELISA. Horizontal bars represent mean Ig levels. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus each CTL group. † P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 versus BLM -treated WT mice.

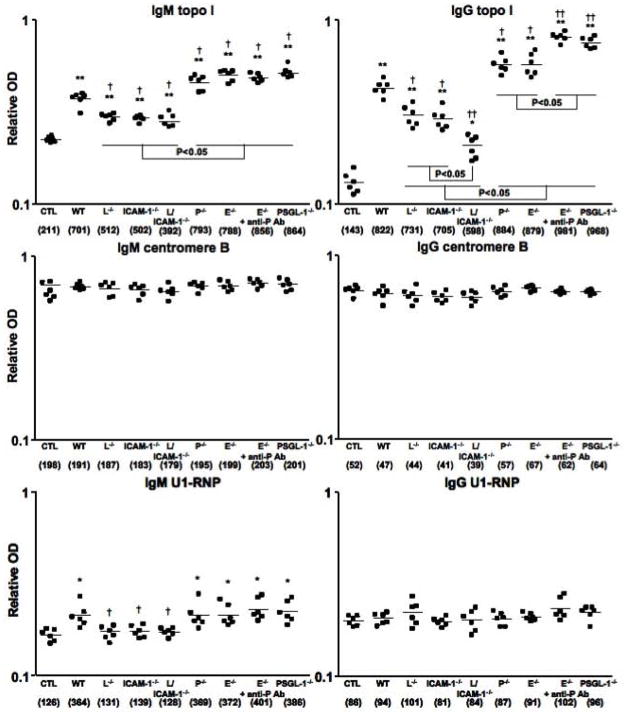

L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 loss inhibited autoantibody production in bleomycin-treated mice, while P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 loss increased it

Antinuclear Abs were rarely detectable in PBS-treated mutant and wild type mice (6%, 1/18, respectively). Antinuclear Abs with a homogenous chromosomal staining pattern were detected in 47% (16/34) of bleomycin-treated wild type mice, which was similar to that in bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− mice (41%, 14/34), E-selectin−/− mice (44%, 15/34), E-selectin−/− mice with blockade of P-selectin (53%, 18/34), and PSGL-1−/− mice (53%, 18/34). By contrast, the frequencies of antinuclear Ab positivity were lower in bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− (29%, 10/34), ICAM-1−/− (26%, 9/34), and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− (12%, 4/34) mice. Autoantibody specificities were further assessed by ELISA (Figure 8). The dilution of sera giving half-maximal OD values in ELISA generated arbitrary units per milliliter that could be directly compared between groups (values in parentheses of Figure 8). Bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/− and ICAM-1−/− mice had decreased IgM autoantibody levels to topo I and U1-RNP and reduced IgG autoantibody levels to topo I relative to bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). L-selectin and ICAM-1 deficiency decreased bleomycin-induced IgM autoantibody levels to topo I and U1-RNP, as well as IgG autoantibody levels to topo I compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). In contrast, bleomycin-treated P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice showed increased IgM autoantibody levels to topo I and increased IgG autoantibody levels to topo I relative to bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). Bleomycin-treated E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice had increased IgM autoantibody levels to topo I, as well as IgG autoantibody levels to topo I compared with bleomycin-treated wild type mice (P < 0.05). Furthermore, IgG anti-topo I Ab production in E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb and PSGL-1−/− mice was greater than those in P-selectin−/− and E-selectin−/− mice (P < 0.05). Thus, bleomycin-induced production of various autoantibodies, especially SSc-specific anti-topo I Ab, decreased by L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency, while it increased by P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 loss.

Figure 8.

Autoantibody levels in sera from bleomycin-treated wild type (WT) mice, L-selectin−/− mice (L−/−), ICAM-1−/− mice (ICAM-1−/−), L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice (L/ICAM-1−/−), P-selectin−/− mice (P−/−), E-selectin−/− mice (E−/−), E-selectin−/− mice treated with anti-P-selectin mAb (E−/− + anti-P Ab), and PSGL-1−/− mice (PSGL-1−/−). Autoantibody levels in sera from PBS-treated WT mice were used as control (CTL). Relative autoantibody levels were determined by Ig subclass-specific ELISA. Values in parentheses represent the dilutions of pooled sera giving half-maximal OD values in autoantigen-specific ELISA, which were determined by linear regression analysis to generate arbitrary units per milliliter that could be directly compared between each group of mice (n = 6 for each). Horizontal bars represent mean Ab levels. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus each CTL group. † P < 0.05, †† P < 0.01 versus BLM-treated WT mice.

Discussion

Cell adhesion molecules play a critical role in the development of several inflammatory diseases (7). In general, inhibition or loss of cell adhesion molecules attenuates inflammatory response in many in vivo experimental models (14, 16–18). Dermal sclerosis of the tight-skin mouse model, a genetic model for SSc, and pulmonary fibrosis induced by intratracheal bleomycin treatment are almost completely eliminated by loss of both L-selectin and ICAM-1, whereas loss of L-selectin or ICAM-1 alone results in less inhibition (14, 18). Similarly, cutaneous contact hypersensitivity response and TNF-α-induced leukocyte rolling are almost completely inhibited by loss of both E-selectin and P-selectin, while loss of each molecule alone leads to less inhibition (19, 20). In the present study, L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency inhibited the development of dermal and pulmonary fibrosis with decreased inflammatory cell infiltration in the bleomycin-induced SSc model (Figures 1 and 2). The inhibitory effect of both L-selectin and ICAM-1 deficiency was significantly greater than that of L-selectin or ICAM-1 deficiency alone. Unexpectedly, P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 deficiency exacerbated inflammatory cell infiltration induced by bleomycin treatment, resulting in deteriorated dermal sclerosis and pulmonary fibrosis, more severe histological change, and increased dermal and pulmonary collagen deposition (Figures 1 and 2). The deterioration effect of E-selectin deficiency with P-selectin blockade and PSGL-1 deficiency was significantly greater than that of P-selectin or E-selectin deficiency alone. Collectively, the results of the present study are the first to reveal cooperative and deterioration roles of L-selectin and ICAM-1 and synergic and inhibitory roles of P-selectin, E-selectin, and PSGL-1 in the development of bleomycin-induced fibrosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated fibrotic effect of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-6 on dermal sclerosis and pulmonary fibrosis (14, 18, 31). Th17 cytokines, such as IL-17, also have fibrogenic effect on dermal, pulmonary, and cardiac fibroblasts (41, 42). Indeed, SSc patients exhibit elevated serum levels of these Th2 and Th17 cytokines (5, 6, 43, 44). These cytokines promote collagen synthesis of fibroblasts via TGF-β1 and COL1A2 signaling (41). Some studies have also shown that IFN-γ, one of the Th1 cytokine, has antifibrotic effect on skin and pulmonary fibrosis (36, 45). Although these findings suggest that Th1, Th2, and Th17 responses associated with disease activity in SSc patients, the mechanism of fibrosis in SSc remains unclear. In this study, we showed that IL-4 or IL-17 stimulation increased proliferation and TGF-β1 and COL1A2 expression of dermal fibroblasts obtained from wild type mice, while IFN-γ inhibited it (Figure 4). The results of this study indicate differential expression levels of these cytokines in cell adhesion molecule-deficient mice treated with bleomycin (Figure 3). Lack of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 reduced IL-4, IL-6, IL-17, and TGF-β1 expression and increased IFN-γ expression in parallel with inhibited dermal sclerosis and pulmonary fibrosis. P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 loss reduced IFN-γ and increased IL-4, IL-6, IL-17, and TGF-β1, which was accompanied by increased dermal and pulmonary fibrosis. Thus, the expression of these cell adhesion molecules alters the cytokine production, which may contribute to the development of skin and lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin treatment.

It is possible that loss of cell adhesion molecule function selectively alters the trafficking pattern of fibrogenic Th2 and Th17 cells and antifibrogenic Th1 cells to the skin and lung. This may result in differential production of cytokines, which may then directly or indirectly influence the development of dermal sclerosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Previous studies have demonstrated that loss of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 function inhibits lung fibrosis induced by intratracheal bleomycin treatment (14), while loss of P-selectin and/or E-selectin function augments it (23). These studies suggest that the mechanisms, by which cell adhesion molecules regulate tissue fibrosis, could be through the regulation of Th1 and Th2 cell infiltration. Two studies have demonstrated that loss of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 function inhibited Th2 cell immigration, inducing Th1 cell infiltration in the allergic lung disease model (46, 47). In addition, Loss of P-selectin, E-selectin, and/or PSGL-1 function prevents Th1 cell infiltration and induce Th2 cell immigration in the cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity and allergic lung disease models (11, 48). Consistent with these findings, the results of this study show that lack of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 inhibited Th2 cell infiltration and induced Th1 cell immigration into BAL fluid, while P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, or PSGL-1 loss decreased Th1 cell infiltration and induced Th2 cell infiltration in the bleomycin-induced SSc model (Figure 5). By contrast, other studies showed that L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 loss decreased Th1 cell infiltration and induced Th2 cell infiltration on inflamed endothelium induced by Th2-delived factors (26, 27). Loss of P-selectin, E-selectin, and/or PSGL-1 function attenuated Th2 cell tethering and rolling on endothelium and epithelium in the intestinal inflammation model (28, 49). Thus, it is likely that each cell adhesion molecule regulates Th cell balance in several ways, according to the tissue site and nature of the inflammation stimuli. In addition, loss of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 decreased Th17 cell infiltration, while P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 loss induced Th17 cell migration (Figure 5). Consistently, a recent study has suggested that loss of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 function inhibited Th17 cell infiltration to the inflammatory sites in the experimental colitis model (29, 50). Furthermore, P-selectin and E-selectin deficiency induces Th17 cells in the neutrophila condition induced by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment (51). Collectively, in the bleomycin-induced SSc model, loss of L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 function may lead to dominant Th1 cell infiltration in parallel with decreased skin and lung fibrosis, while P-selectin loss, E-selectin loss with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 loss may induce dominant Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration that is accompanied by deteriorated skin and lung fibrosis.

Our flow cytometric analysis of polarized CD4+ T cells exhibited differential expression of LFA-1 and PSGL-1 and binding ability for ICAM-1, P-selectin, and E-selectin, while the frequencies of LFA-1+ or PSGL-1+ cells were similar among Th0, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells (Figure 6). Previously, blocking studies using anti-LFA-1 or PSGL-1 mAbs have suggested that Th cell migration mainly depends on LFA-1 or PSGL-1, though virtually all lymphocytes express LFA-1 and PSGL-1 (11, 46). Although the mechanism, by which Th cell infiltration is regulated by LFA-1 and PSGL-1, remains unclear, our present study is the first to suggest that expression intensity of LFA-1 and PSGL-1 contributes to Th cell infiltration. LFA-1 was highly expressed by Th2 and Th17 cells compared with Th0 cells, while Th1 cells showed decreased intensity levels of LFA-1 expression. Th1 cells exhibited increased expression intensity of PSGL-1, whereas Th2 and Th17 cells showed lower intensity levels of PSGL-1 expression. Similarly, ICAM-1 binding ability of Th2 and Th17 cells was higher than that of Th0 cells, while Th1 cells showed lower binding ability for ICAM-1. Th1 cells exhibited higher P-selectin and E-selectin binding ability, whereas Th2 and Th17 cells showed lower binding ability for P-selectin and E-selectin. These expression and binding ability patterns may in part explain why Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration was inhibited by ICAM-1 deficiency and why Th1 cell migration was suppressed by E-selectin, P-selectin, or PSGL-1 deficiency (Figure 5).

L-selectin and LFA-1 play important roles in antigen sensitization, because these adhesion molecules mediate naive T cell migration into the draining lymph nodes (52, 53). Furthermore, these adhesion molecules are one of the co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of antigen presenting cells (52–54). In this study, we used the bleomycin-induced SSc model, which does not require antigen sensitization (30, 31). Therefore, we can exclude the possible role of these adhesion molecules on the sensitization phase. During T cell differentiation, activated L-selectin is shed from the cell surface by proteolytic cleavage by an as yet unidentified membrane-bound metalloprotease (“sheddase”) (55). Indeed, in this study, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells did not express L-selectin. However, previous studies show that L-selectin plays important roles in passive Arthus reaction and intratracheal bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, which do not also require antigen sensitization (14, 21). In addition, rapidly activated-L-selectin shedding enhances LFA-1 expression and the LFA-1/ICAM-1 binding ability (7, 55). Therefore, LFA-1 expression intensity also reflects L-selectin activity, which could account for the diminishing effect of L-selectin deficiency on Th2 and Th17 immigration. Collectively, the results of this study suggest that Th1 cell infiltration is mainly regulated by PSGL-1 and PSGL-1 counterreceptors, P-selectin and E-selectin, while Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration is mainly controlled by L-selectin, LFA-1, and a LFA-1 counterreceptor, ICAM-1. Furthermore, in bleomycin-treated L-selectin−/−, ICAM-1−/−, and L-selectin/ICAM-1−/− mice, the reduced rate of Th17 cell infiltration was greater than those of Th2 cell infiltration. This may reflect that Th17 cell infiltration strongly depends on LFA-1 compared with Th2 cell infiltration.

As we reported previously, bleomycin treatment induced the production of autoantibodies, especially SSc-specific anti-topo I Ab, and hyper-γ-globulinemia, both of which are central features of human SSc (31). In this study, L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency reduced these autoimmune abnormalities, while P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 deficiency deteriorated it (Figures 7 and 8). Recent studies showed that Th1 cells supported Ig isotype switching to IgG2a. In contrast, Th2 cells provided efficient help for B cell activation and class switching to IgG1 (56, 57). IFN-γ promotes IgG2a class switching while IL-4 promotes IgG1 class switching (56–58). Therefore, concentrations of serum IgG2a and IgG1 reflect Th1 and Th2 responses in vivo (56–59). However, in this study, serum levels of each Ig isotype associated with tissue damage, such as inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrosis, rather than Th1 and/or Th2 cytokine production. It has been previously hypothesized that immune responses to autoantigens are induced by cryptic self-epitopes that are generated by the modification of self-antigens (60). The exposure of cryptic self-epitopes activates potentially autoreactive T cells that have not previously encountered the cryptic self, thereby breaking T cell tolerance. In this regard, bleomycin-induced tissue injury has been shown to induce modification of the self-antigens, such as Fas-dependent and/or oxygen species-induced metal-dependent cleavage of topo I (61). Moreover, apoptosis is detected in the skin of human SSc patients and bleomycin-induced SSc model mice, which associated with the severity of tissue damage (61, 62). Therefore, the production of anti-topo I Ab may be related to the modification of topo I by bleomycin-induced tissue injury. In this study, L-selectin and/or ICAM-1 deficiency reduced bleomycin-induced tissue injury, which paralleled with decreased autoantibody and Ig production (Figures 1, 2, 7, and 8). By contrast, P-selectin deficiency, E-selectin deficiency with or without P-selectin blockade, and PSGL-1 deficiency exacerbated bleomycin-induced tissue injury, which was accompanied by increased antoantibody and Ig production (Figures 1, 2, 7, and 8). Thus, these regulations of tissue injury partially explain that cell adhesion molecule deficiency contribute to autoantibody and Ig production in the bleomycin-induced SSc model.

To date, there have been few studies addressing an in vivo role of cell adhesion molecules in SSc models. This is the first systematic study to reveal relative contribution of adhesion molecules, L-selectin, ICAM-1, LFA-1, P-selectin, E-selectin, and PSGL-1 in the development of dermal sclerosis and pulmonary fibrosis in the bleomycin-induced SSc mouse model. These results provide additional clues to understanding the complexity of the pathogenesis of SSc.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of Research on Intractable Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (to S. Sato and Y. Yoshizaki) and National Institutes of Health, USA grants CA96547, CA105001, and AI56363 (to T. F. Tedder).

We thank Ms. M. Yozaki, A. Usui, K. Shimoda, Y. Yamada, and M. Matsubara for technical assistance.

Nonstandard abbreviations used in this paper

- SSc

systemic sclerosis

- BAL

broncho-alveolar lavage

- topo I

topoisomerase I

- CENP B

centromeric protein B

- RNP

ribonucleoprotein

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- Th1

IFN-γ-producing Th subset

- Th2

IL-4-producing Th subset

- Th17

IL-17-producing Th subset

- PSGL-1

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr, Rowell N, Wollheim F. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): Classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuwana M, Okano Y, Kaburaki J, Inoko H. Clinical correlation with HLA type in Japanese patients with connective tissue disease and anti-U1 small nuclear RNP antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:938–942. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato S, Fujimoto M, Hasegawa M, Takehara K. Altered blood B lymphocyte homeostasis in systemic sclerosis: expanded naive B cells and diminished but activated memory B cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1918–1927. doi: 10.1002/art.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, Arriola E, Silver R, Strange C, Bolster M, Seibold JR, Riley DJ, Hsu VM, Varga J, Schraufnagel DE, Theodore A, Simms R, Wise R, Wigley F, White B, Steen V, Read C, Mayes M, Parsley E, Mubarak K, Connolly MK, Golden J, Olman M, Fessler B, Rothfield N, Metersky M. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Needleman BW, Wigley FM, Stair RW. Interleukin-1, interleukin-2, interleukin-4, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-a, and interferon-g levels in sera from patients with scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:67–72. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata M, Fujimoto M, Matsushita T, Hamaguchi Y, Hasegawa M, Takehara K, Komura K, Sato S. Clinical association of serum interleukin-17 levels in systemic sclerosis: is systemic sclerosis a Th17 disease? J Dermatol Sci. 2008;50:240–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tedder TF, Li X, Steeber DA. The selectins and their ligands: adhesion molecules of the vasculature. Adv Mol Cell Biol. 1999;28:65–111. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varki A. Selectin ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7390–7397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McEver RP, Cummings RD. Role of PSGL-1 binding to selectins in leukocyte recruitment. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:S97–S103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borges E, Tietz W, Steegmaier M, Moll T, Hallmann R, Hamann A, Vestweber D. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on T helper 1 but not on T helper 2 cells binds to P-selectin and supports migration into inflamed skin. J Exp Med. 1997;185:573–578. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asa D, Raycroft L, Ma L, Aeed PA, Kaytes PS, Elhammer AP, Geng JG. The P-selectin glycoprotein ligand functions as a common human leukocyte ligand for P- and E-selectins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11662–11670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dustin ML, Rothlein R, Bhan AK, Dinarello CA, Springer TA. Induction by IL 1 and interferon-gamma: tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function of a natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1) J Immunol. 1986;137:245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamaguchi Y, Nishizawa Y, Yasui M, Hasegawa M, Kaburagi Y, Komura K, Nagaoka T, Saito E, Shimada Y, Takehara K, Kadono T, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Sato S. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and L-selectin regulate bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1607–1618. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64439-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuse T, Teramoto S, Katayama H, Sudo E, Ekimoto H, Mitsuhashi H, Uejima Y, Fukuchi Y, Ouchi Y. ICAM-1 mediates lung leukocyte recruitment but not pulmonary fibrosis in a murine model of bleomycin-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:71–77. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13107199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanaba K, Komura K, Horikawa M, Matsushita Y, Takehara K, Sato S. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is required for the development of cutaneous vasculitis induced by immune complex deposition. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:374–382. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada Y, Hasegawa M, Kaburagi Y, Hamaguchi Y, Komura K, Saito E, Takehara K, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Sato S. L-selectin or icam-1 deficiency reduces an immediate-type hypersensitivity response by preventing mast cell recruitment in repeated elicitation of contact hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 2003;170:4325–4334. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsushita Y, Hasegawa M, Matsushita T, Fujimoto M, Horikawa M, Fujita T, Kawasuji A, Ogawa F, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Takehara K, Sato S. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 deficiency attenuates the development of skin fibrosis in tight-skin mice. J Immunol. 2007;179:698–707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frenette PS, Mayadas TN, Rayburn H, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. Susceptibility to infection and altered hematopoiesis in mice deficient in both P- and E-selectins. Cell. 1996;84:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bullard DC, Kunkel EJ, Kubo H, Hicks MJ, Lorenzo I, Doyle NA, Koerschuk CM, Ley K, Beaudet AL. Infectious susceptibility and severe deficiency of leukocyte rolling and recruitment in E-selectin and P-selectin double mutant mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2329–2336. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanaba K, Kaburagi Y, Takehara K, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Sato S. Relative contributions of selectins and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 to tissue injury induced by immune complex deposition. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1463–1473. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bullard DC, Mobley JM, Justen JM, Sly LM, Chosay JG, Dunn CJ, Lindsey JR, Beaudet AL, Staite ND. Acceleration and increased severity of collagen-induced arthritis in P-selectin mutant mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:2844–2849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horikawa M, Fujimoto M, Hasegawa M, Matsushita T, Hamaguchi Y, Kawasuji A, Matsushita Y, Fujita T, Ogawa F, Takehara K, Steeber DA, Sato S. E- and P-selectins synergistically inhibit bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:740–749. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenkranz AR, Mendrick DL, Cotran RS, Mayadas TN. P-selectin deficiency exacerbates experimental glomerulonephritis: a protective role for endothelial P-selectin in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:649–659. doi: 10.1172/JCI5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He X, Schoeb TR, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Zinn KR, Kesterson RA, Zhang J, Samuel S, Hicks MJ, Hickey MJ, Bullard DC. Deficiency of P-selectin or P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 leads to accelerated development of glomerulonephritis and increased expression of CC chemokine ligand 2 in lupus-prone mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:8748–8756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savage ND, Harris SH, Rossi AG, De Silva B, Howie SE, Layton GT, Lamb JR. Inhibition of TCR-mediated shedding of L-selectin (CD62L) on human and mouse CD4+ T cells by metalloproteinase inhibition: analysis of the regulation of Th1/Th2 function. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2905–2914. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2905::AID-IMMU2905>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thauland TJ, Koguchi Y, Wetzel SA, Dustin ML, Parker DC. Th1 and Th2 cells form morphologically distinct immunological synapses. J Immunol. 2008;181:393–399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangan PR, O’Quinn D, Harrington L, Bonder CS, Kubes P, Kucik DF, Bullard DC, Weaver CT. Both Th1 and Th2 cells require P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 for optimal rolling on inflamed endothelium. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1661–1675. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61249-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim HW, Lee J, Hillsamer P, Kim CH. Human Th17 cells share major trafficking receptors with both polarized effector T cells and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:122–129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T, Takagawa S, Katayama I, Yamazaki K, Hamazaki Y, Shinkai H, Nishioka K. Animal model of sclerotic skin. I: Local injections of bleomycin induce sclerotic skin mimicking scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:456–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshizaki A, Iwata Y, Komura K, Ogawa F, Hara T, Muroi E, Takenaka M, Shimizu K, Hasegawa M, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF, Sato S. CD19 regulates skin and lung fibrosis via Toll-like receptor signaling in a model of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1650–1663. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbones ML, Ord DC, Ley K, Radich H, Maynard-Curry C, Capon DJ, Tedder TF. Lymphocyte homing and leukocyte rolling and migration are impaired in L-selectin (CD62L) deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1:247–260. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashcroft T, Simpson JM, Timbrell V. Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a numerical scale. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:467–470. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.4.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Domeij H, Modeer T, Quezada HC, Yucel-Lindberg T. Cell expression of MMP-1 and TIMP-1 in co-cultures of human gingival fibroblasts and monocytes: the involvement of ICAM-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:1825–1833. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Ramallo E, Marques T, Prats N, Beleta J, Kunkel SL, Godessart N. Resident cell chemokine expression serves as the major mechanism for leukocyte recruitment during local inflammation. J Immunol. 2002;169:6467–6473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura T, Ishii Y, Morishima Y, Shibuya A, Shibuya K, Taniguchi M, Mochizuki M, Hegab AE, Sakamoto T, Nomura A, Sekizawa K. Treatment with alpha-galactosylceramide attenuates the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2004;172:5782–5789. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao Y, Li N, Fei R, Chen Z, Zheng S, Zeng X. P-Selectin-mediated acute inflammation can be blocked by chemically modified heparin, RO-heparin. Mol Cells. 2005;19:350–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silver RM, Miller KS, Kinsella MB, Smith EA, Schabel SI. Evaluation and management of scleroderma lung disease using bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Med. 1990;88:470–476. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90425-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakagome K, Dohi M, Okunishi K, Tanaka R, Miyazaki J, Yamamoto K. In vivo IL-10 gene delivery attenuates bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the production and activation of TGF-beta in the lung. Thorax. 2006;61:886–894. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun RK, Ferrick C, Neubauer P, Sjoding M, Sterner-Kock A, Kock M, Putney L, Ferrick DA, Hyde DM, Love RB. IL-17 producing gammadelta T cells are required for a controlled inflammatory response after bleomycin-induced lung injury. Inflammation. 2008;31:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s10753-008-9062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakkas LI, I, Chikanza C, Platsoucas CD. Mechanisms of Disease: the role of immune cells in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:679–685. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venkatachalam K, Mummidi S, Cortez DM, Prabhu SD, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Resveratrol inhibits high glucose-induced PI3K/Akt/ERK-dependent interleukin-17 expression in primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2078–H2087. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01363.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roumm AD, Whiteside TL, Medsger TA, Jr, Rodnan GP. Lymphocytes in the skin of patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Quantification, subtyping, and clinical correlations. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:645–653. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deleuran B, Abraham DJ. Possible implication of the effector CD4+ T-cell subpopulation TH17 in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:682–683. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giacomelli R, Cipriani P, Fulminis A, Barattelli G, Matucci-Cerinic M, D’Alo S, Cifone G, Tonietti G. Circulating g/d T lymphocytes from systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients display a T helper (Th) 1 polarization. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:310–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SH, Prince JE, Rais M, Kheradmand F, Ballantyne CM, Weitz-Schmidt G, Smith CW, Corry DB. Developmental control of integrin expression regulates Th2 effector homing. J Immunol. 2008;180:4656–4667. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuzaki S, Shinozaki K, Kobayashi N, Agematsu K. Polarization of Th1/Th2 in human CD4 T cells separated by CD62L: analysis by transcription factors. Allergy. 2005;60:780–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Austrup F, Vestweber D, Borges E, Lohning M, Brauer R, Herz U, Renz H, Hallmann R, Scheffold A, Radbruch A, Hamann A. P- and E-selectin mediate recruitment of T-helper-1 but not T-helper-2 cells into inflammed tissues. Nature. 1997;385:81–83. doi: 10.1038/385081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonder CS, Norman MU, Macrae T, Mangan PR, Weaver CT, Bullard DC, McCafferty DM, Kubes P. P-selectin can support both Th1 and Th2 lymphocyte rolling in the intestinal microvasculature. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1647–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61248-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bendjelloul F, Rossmann P, Maly P, Mandys V, Jirkovska M, Prokesova L, Tuckova L, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H. Detection of ICAM-1 in experimentally induced colitis of ICAM-1-deficient and wild-type mice: an immunohistochemical study. Histochem J. 2000;32:703–709. doi: 10.1023/a:1004191825644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stark MA, Huo Y, Burcin TL, Morris MA, Olson TS, Ley K. Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils regulates granulopoiesis via IL-23 and IL-17. Immunity. 2005;22:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Seventer GA, Shimizu Y, Horgan KJ, Shaw S. The LFA-1 ligand ICAM-1 provides an important costimulatory signal for T cell receptor-mediated activation of resting T cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:4579–4586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Catalina MD, Carroll MC, Arizpe H, Takashima A, Estess P, Siegelman MH. The route of antigen entry determines the requirement for L-selectin during immune responses. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2341–2351. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]